Chapter 3 Notes, Part B: Chicago Newspapers Circa 1972

Not your father's footnotes. Fun. Lots of pictures.

FYI, if you’re not a regular reader: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” is a hybrid novel/1972 Chicago primer, posting one novel chapter per month. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972. Each chapter comes with fun Notes on key topics that pop up as our story progresses. Today, we look at Chicago newspapers circa 1972 because in those far away days, newspapers were part of everyone’s life. For more on what the heck the book is all about, check out the well-named ABOUT page. Subscribe for free.

Like Columbo, everybody Steve knew got a newspaper delivered to their house.

Newspapers were a bit like people, even relatives. What kind of folks did your family hang around with? Did they eat breakfast with the Sun-Times, the Tribune, or the Defender? In the evening, who did your family invite inside to sit in the front room—the Daily News or Chicago Today?

Your own newspaper—the typeface, the width of the columns, the style of the headlines—looked as familiar and natural as your mom’s face. Reading someone else’s paper was like seeing Mom with a different pair of glasses or even a nose job.

People were no more likely to switch newspapers than trade grandparents. If you read the Sun-Times or Chicago Today, you didn’t want somebody else’s Daily News any more than you’d want to kiss their gramma.

If you came from a working class family like Steve’s, you especially didn’t want somebody else’s Tribune. Running across a Tribune at someone’s house in 1972 was still sometimes like bumping into cantankerous old Colonel Robert R. McCormick, the deceased early 20th century owner and physical manifestation of the Tribune.

As you see from the 1972 Newspaper Medley, there were four major dailies left in 1972, plus the smaller Chicago Daily Defender, which focused on Chicago’s Black community. There were many weekly or biweekly neighborhood and ethnic newspapers too. People often subscribed to one of the dailies, plus a neighborhood or ethnic paper. In Roseland, Steve’s neighbors added the Calumet Index and/or the South End Reporter.

As mentioned earlier, the four major dailies were by definition at that time still mainly the white and male press. The major dailies really began hiring Black reporters in the ‘60s, particularly following 1968. As the ‘60s and ‘70s progressed, the major dailies were slowly increasing coverage of Black communities and politics. In ‘72, there are periods when the dailies covered the Rev. Jesse Jackson almost as closely as Mayor Daley.

You might be surprised to know that the 1972 major dailies featured local Black columnists—Lu Palmer in the Daily News, Vernon Jarrett in the Tribune, and Ellis Cose in the Sun-Times—plus nationally syndicated writers Carl Rowan and William Raspberry. By 1972, they also ran content aimed directly at the growing Chicago Latino community. The Sun-Times ran a column in Spanish by Ruben Cruz.

Even more surprising perhaps, Black sportswriter Wendell Smith went to work for the Herald-American in 1948, and the Tribune beat the other major papers in featuring a local Black columnist. The Trib hired Roi Ottley in 1953, a New Yorker who’d gained initial national attention for his 1943 book on Black life in Harlem in the ‘20s and ‘30s, "New World A-Coming: Inside Black America.” Ottley moved to Chicago and worked first at the Defender before the Tribune hired him for a freelance weekly column on Black Chicago, which quickly became biweekly until Ottley’s untimely death in 1960.

In 1972, a few women journalists like Lois Wille, Diane Monk, and Betty Washington (originally of the Defender) had broken into regular news beats at the major dailies over the course of the ‘60s, so female bylines on major news stories in 1972 weren't bizarre. Others like Mary Knoblauch at Chicago Today were moving into editorial positions. Women had already been in key positions at the Defender, such as Audrey Weaver, city editor by the 1940s. The Defender’s Ethel Payne, called “First Lady of the Black Press,” moved to Washington by the early 50s and became the first African-American woman in the White House press corps during the Eisenhower administration, returning to Chicago in 1973 to become the Defender’s associate editor.

The “women’s pages” in the major dailies were evolving too, though they had a ways to go, like everything else in 1972. First consider where the women’s sections started, though. Mary Knoblauch began at Chicago’s American in 1963, while attending Northwestern, as a secretary in the women’s department.

“They had a five-person society staff and that’s what they did mostly--debutante parties and women’s luncheons,” Knoblauch recalls—and she had a ball. “You got to meet a lot of the famous women of this town who were in charge of all the society stuff, and I got to meet Michael Butler, who put on ‘Hair’ here---it just was a hoot.”

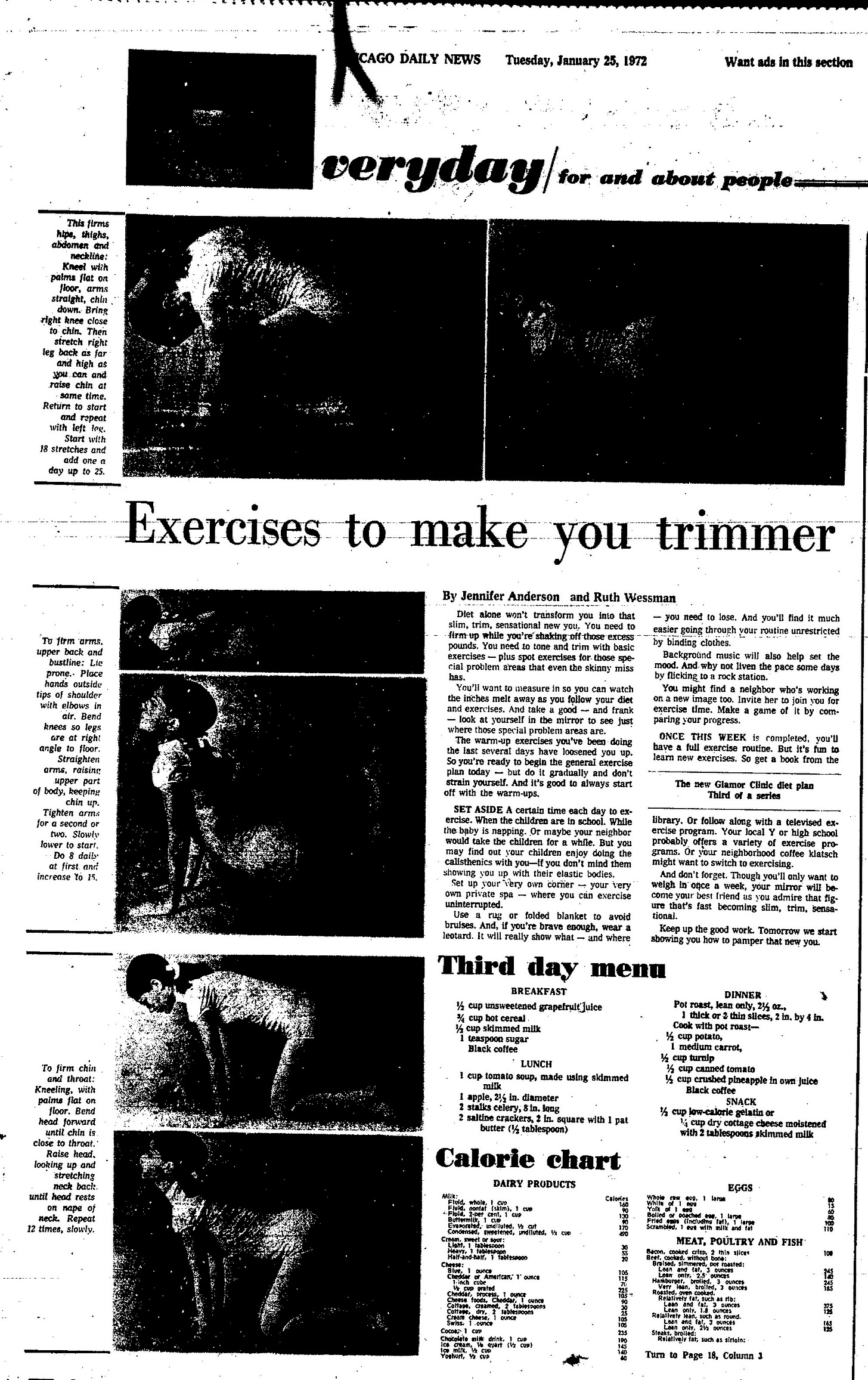

By ‘72, the Daily News and Chicago Today had renamed their weekday women’s sections in gender neutral terms—“Everyday/for and about people,” and “Family today,” respectively. Content sometimes still leaned heavily on, say, “Knit Notes: These pullovers a pushover to make”'; a full page of new women’s shoe styles; and “Dry milk cuts cost of meals.”

But many days, the articles were as modern as anyone could ask, including a series on open marriage; a center for poor families with mentally challenged kids; and a survey of different ethnic neighborhoods. When the revamped sections tilted toward their old focus, it could be argued they were correctly serving a female readership that still largely wanted that content. Even in 2022, you would not be incorrect to say female readers are interested in fashion, cooking, and knitting—all of which are currently hip—and where does that belong if not in a separate section after the news pages? Add yoga, and with some tweaking, you could read it today.

So 1972 was a fluid time; change was happening, though still just beginning.

We’ll look at each daily newspaper briefly here, and return with Optional History Chapters on each. There’s too much great writing in all the papers, and too many great stories about them, to stuff everything in one place.

By the way, I’ll continue contacting reporters who were working in 1972, getting views and stories about their own papers and the others. I wish I’d interviewed the entire ‘72 staff of each paper, but even a Substack must set deadlines. Many voices are sadly no longer available. Unfortunately, I haven’t yet made contact with any Defender reporters of that time. But you never know who may turn up as I move on. The additional input will go mainly into the Optional History Chapters on individual papers. I’ll notify subscribers if there are enough additions to this post.

The Chicago Tribune

The Tribune has always drawn the most—and most ardent—opinions. Several reasons for that. So we’ll give the Trib more space here in this combined newspaper post, to explain its unique, towering place in the Chicago newspaper world.

Let’s stipulate first that despite the flack the historic Tribune will take here, despite its former rabid politics, the paper was always a substantial, integral documentation of Chicago. While it’s sometimes interesting to see what stories the Tribune ignored, typically you can pick a topic and trace its history in the Trib’s pages. And any issue featured plenty of good reads. Let’s not forget that Ring Lardner wrote the “In the Wake of the News” sports column for six years. I’ve wallowed in the Tribune simply because its archives are completely digitized, but it hasn’t been a hardship. No one holds a gun to my head to read every Tower Ticker column by Herb Lyon that turns up in the search returns. I just can’t help it.

Which is why the new Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter has so much amazing material to draw upon. Readers here will no doubt be interested in checking it out.

The post-Colonel Tribune, it goes without saying, has employed too many fantastic journalists to list here.

In fact, even the Colonel’s Tribune wasn’t as stuffy and boring as many people remember—just like that babysitter when you were a kid probably wasn’t as mean as you thought. Case in point, just last week I checked to see if the Trib archives could quickly confirm where the Chicago Avenue Police Court was in 1972. It could, and then I wasted too much time dipping into the fun Police Court stories that popped up, because regardless of its uptight reputation, the Tribune did cover crime. And how do you not read 1962’s “Cabbie Calls Zealous Cop A Stooge for Homicide Unit,” in which “roly-poly” mobster Albert (Obbie) Frabotta stomps out cursing reporters, lunges at one photographer, and his associate tries to kick the Tribune photographer? Any article that describes a mobster as “roly-poly” is one I don't want to miss.

Post-Colonel, the Tribune underwent a massive transformation starting under editor Clayton Kirkpatrick, who arrived in 1969. As renowned Chicago writer Patrick Reardon explained in Kirkpatrick’s 2004 obituary, Kirkpatrick “rescued the Chicago Tribune from its hidebound and potentially debilitating traditions to return it to its place as one of the nation's most influential newspapers.” Reardon wrote that for the Tribune, being a veteran Trib reporter. So both Reardon and the obit are fine examples of Kirkpatrick’s accomplishment. (Kirkpatrick also tried his darnedest to lure Mike Royko away from the Sun-Times, a job only Rupert Murdoch could accomplish.)

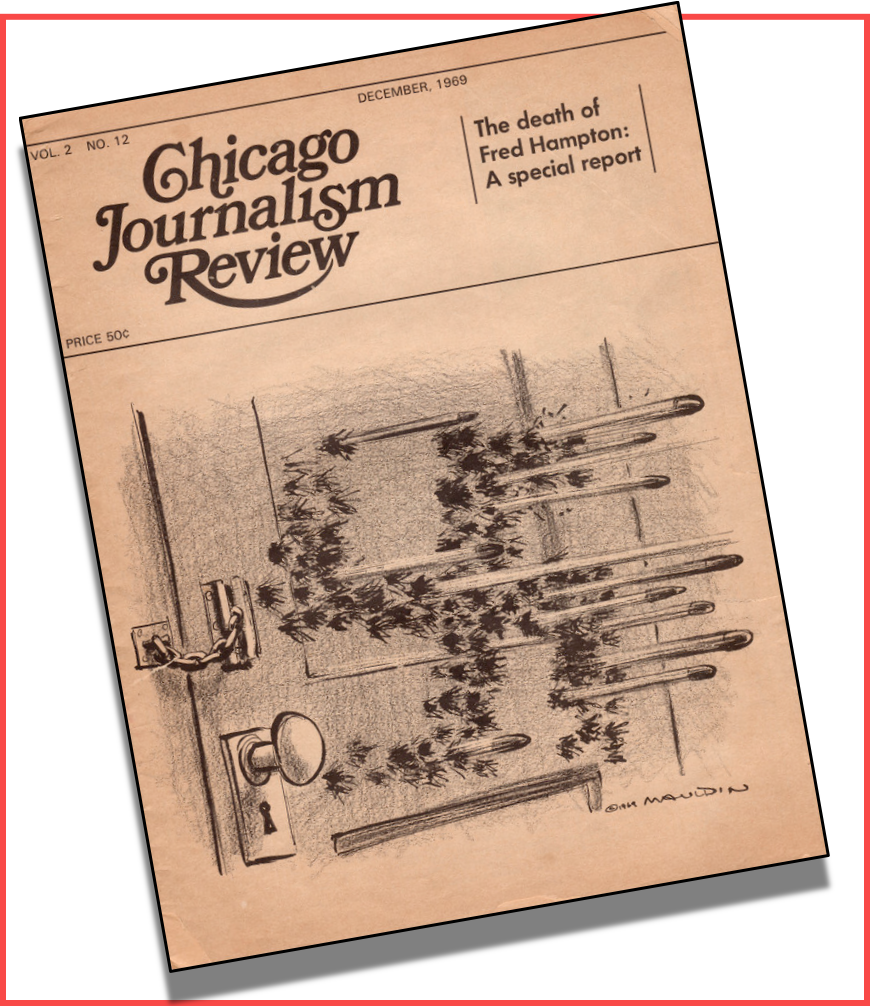

Former Daily News education reporter Hank De Zutter, who founded the Community Media Workshop with Thom Clark, helped start the Chicago Journalism Review after deciding none of the city’s papers had adequately covered the 1968 Democratic convention and the Grant Park police riot. De Zutter also taught journalism in the early ‘70s, and he used to start out by directing students to compare the same story in all the Chicago papers. Each paper’s take was so different, he could count on a Rashomon effect.

The Tribune, De Zutter wrote in the CJR, had been “perversely unique”—so right-wing that when Robert F. Kennedy “dared to question American involvement in Vietnam, the World’s Greatest Newspaper (as it called itself) screamed its rage in a front-page editorial entitled ‘Ho Chi Kennedy.’”

But De Zutter’s old Rashomon lesson was “no longer possible,” he wrote in a 1975 CJR. “Now the differences…are marginal, and so much of the reporting and writing interchangeable.”

So why is it that Steve Bertolucci’s working class family would never have had a copy of the Tribune in their 1972 Roseland bungalow’s kitchen dinette at 12426 S. Wabash?

Why did some people even then avoid the Tribune, rag on the Tribune, even hate the Tribune?

First, the Trib has been the big kid on the newspaper block since it topped the Daily News’ circulation in 1918. And everybody likes to punch up. For both readers and reporters from the other papers, the Tribune was the conservative, rich establishment.

A comparison of the daily Chicago newspaper headquarters left in 1972 illustrates the relationship between the Tribune and everyone else.

The four major dailies were owned by two companies, while the Defender owned itself. The Tribune owned itself and Chicago Today, previously Chicago’s American. Field Enterprises owned the Sun-Times and the Daily News.

The Tribune staff looked down on the city from the gothic spires of Tribune Tower, 435 N. Michigan Avenue.

The Trib allowed its poor cousin Chicago Today to camp in the adjoining smaller building once known as the WGN Building, 445 N. Michigan Avenue, with its newsroom on the fourth floor, rear. Physically, the Trib and American/Today editorial staffs were completely separated, though the two papers shared some business offices and the gigantic printing operation. For the American/Chicago Today staff, you can’t help but think it sounds a bit like Harry Potter’s closet bedroom underneath the Dursley’s stairs.

Below, you get a good look at the former WGN Building on the corner of Michigan and upper Illinois, adjoining Tribune Tower. It’s not a slum, but it’s not a tower, is it.

The Sun-Times and Daily News shared the hulking headquarters at 401 N. Wabash (now site of Trump Tower). Many Chicagoans have a soft spot for the old Sun-Times building and miss it, including myself, but c’mon. As Sun-Times columnist Neil Steinberg puts it, “They were in the gothic horror show of Tribune Tower when we were in this ugly trapezoidal barge on the river.”

In 1972, the Defender was ensconced at the former home of the Illinois Automobile Club, built in 1936 and renovated for the paper in 1960. It’s a wonderful building at 2400 S. Michigan on the old Motor Row—and an astounding achievement by both Defender founder Robert S. Abbott and his successor John Sengstacke. The Defender began in Abbott’s landlady’s kitchen with “an initial investment of 25 cents and a press run of 300 copies” according to the Defender’s website. But again, it isn’t Tribune Tower.

For reporters, Trib hate also stemmed from competition, which remained fierce throughout the 20th century. Naturally it was most intense in the early days when reporters were seemingly a law unto themselves. Because it’s most fun, we’ll take an example from those Front Page days, one that simultaneously represents another phenomenon—reporters who hated the Tribune because they got fired from it.

From Jack McPhaul’s hilarious “Deadlines and Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism”:

“Never having been an employee of Col. McCormick I was denied that special joie de vivre experienced by…ex-Trib men in the execution of a ploy discomforting to the Tower,” McPhaul writes to introduce the tale of a fired Trib reporter who’d gone to Hearst’s Herald-Examiner. The Examiner gets word of a murdered man with a common name, say John Jones of the North Side. He was killed in a woman’s apartment, a scandal at that time. The Examiner sends a reporter out. He finds a North Side apartment occupied by a John Jones, flashes a police badge, and tells the building superintendent to let him in the apartment because the tenant’s been murdered. Once in, the reporter gleefully collects diaries and other loot to bring back to the office, then starts back out.

At this point the door opened and the super gave a great cry, as one will at the sight of the walking dead. “Sergeant, here is Mr. Jones now!” The reporter didn’t flinch. “Jones,” he said severely, “you have caused us a great deal of trouble. Now hop upstairs and phone the detective bureau. Tell ‘em to take you off the death list.”

En route to the Hearst Building the pair made a stop—at Tribune Tower. There they instructed a cab driver to return a package to Mr. Jones with the explanation that the Tribune sent its regrets. Presently Jones was on the phone threatening the Tribune with suits for illegal entry and invasion of privacy.

McPhaul notes that one of his readers may find “times when he will be inclined to doubt,” but McPhaul insists that all his stories come from “my personal knowledge and experience during 39 years of Chicago newspapering. Others will be sworn to by sober men.”

The important thing isn’t that this individual story is true. The spirit behind the story is true: Tribune hatred and envy.

What about competition between papers owned by the same company? Oh yes! Take the Sun-Times and Daily News, their city rooms sharing a huge floor, split down the middle by a wire room, after Field Enterprises purchased the News.

John McCormick gives an example circa ‘72 from some formative college years in the early ‘70s, when he worked as a Daily News night copy boy under then-night city editor Rob Warden. McCormick would go on to a distinguished career first at Newsweek and then with the Tribune, retiring recently as editorial page editor. Warden’s career would be no less impressive—he went on to editing and publishing Chicago Lawyer, then founded the Center for Wrongful Convictions and later Injustice Watch.

Daily News night city editor Warden would sometimes send copy boy McCormick across the floor into Sun-Times territory on a spying mission.

“There was only one reason we could go [into the Sun-Times city room]: to go to the Library Return drawer,” McCormick recalls. “It was like a filing cabinet. People would put envelopes in there with material to return to the morgue.”

“Warden would send a kid over to see what the Sun-Times was working on that wasn’t in the paper yet,” says McCormick. “He was especially interested in whatever Art Petacque was working on.”

“And Petacque would play along,” says McCormick. “Petacque would go to the morgue and ask for files on I don’t know, Kaiser Wilhelm, and he’d walk it straight to the return drawer. I’d go back to Warden” —McCormick shrugs, imitating his old copyboy self-- “‘I don’t know--here’s a file on Kaiser Wilhelm.’”

Things could get less friendly as well. Leonard Aronson’s GOSSIP column in the April 1973 Chicago Journalism Review relates a run-in between Sun-Times columnist Tom Fitzpatrick and Daily News columnists Mike Royko and Mort Edelstein:

“It was a point of great pride” to get stories in the paper by deadline in order to beat the others, McCormick recalls. Once, an education reporter rushed in just before deadline. “It was me and another copy boy, and [the reporter is] typing like mad. When he’d get to the end of a page, one of us would take the typewriter and the other one would put a new typewriter in front of him with new paper in it, and he’d just keep typing. I was like, ‘This is the big city.’ We didn’t do that in Dubuque.”

Of course, even hate and envy evolve. It’s instructive to fast forward to the ‘80s for a moment. The perfect opposing ‘80s pair for us are, of course, Neil Steinberg at the Sun-Times…

…and Eric Zorn at the Tribune.

Steinberg landed at the Sun-Times in 1987:

“That was the aftershock of the explosion of the Daily News, the original sin, the crucifixion of Chicago journalism,” he explains in just the apocalyptic terms you can count on. “Everything was before or after that. When that fell apart, everyone sort of scattered. I arrived in the post-Royko going to the Tribune. Royko going to the Trib changed it from being Colonel McCormick’s xenophobic rag to the place where Mike Royko lived, so that classed it up.”

And competition was still a big issue at the Sun-Times, says Steinberg with no prompting: “There was a horror that the Tribune would get something that we wouldn’t. An expectation that even though we were undergunned--the Tribune was the locus of significance. If they had a story about strawberry jam, then strawberry jam was a story and we had to get on it.”

Eric Zorn’s comments in email were more of a shrug. The Trib, he writes, “considered the NYT, WaPo, WSJ and maybe the LATimes as its competition, not the little tabloid across the street. Word was that if you were ever to go to your supervisor and say you had an offer from the Sun-Times, the supervisor was duty bound to offer you a handshake of farewell and refuse to negotiate.”

But back to 1972. People like Steve’s family didn’t read the Tribune in 1972 because the paper was still evolving into the paper you know today—imperfect as all human enterprises are, but on a reasonable scale. Remember we mentioned that looking at somebody’s Tribune in 1972 could still be like bumping into cantankerous old Colonel Robert R. McCormick?

Colonel Robert McCormick took over his family’s newspaper business in 1911, and from that moment the Tribune became a wood pulp version of the Colonel. The Colonel/Tribune was so ferociously conservative, he called President Herbert Hoover “the greatest state socialist in history.” Naturally, he considered Franklin D. Roosevelt a Communist—“Although I don’t know if he carried a card,” the Colonel told a reporter in 1951.

But the Colonel didn’t change the Tribune’s direction so much as he simply continued steering it on a hard Republican course. By fixing on the Republican Party as its North Star, the Trib naturally traveled from staunch abolitionist in the 1850s to conservative, well-to-do, and rabidly anti-Communist in the early to mid-20th century.

The Chicago Daily Tribune was founded in 1847—acquiring that precise name a few years later. That makes the Trib Chicago’s oldest surviving newspaper with the same name. The Sun-Times stakes its own claim to “oldest,” which we’ll detail later. As the decades went by, other city papers faded away or merged, changing and hyphenating their names. The Tribune steamed ahead, leaving competitors to drown in its wake, or occasionally plucking them out of the water and heaving them on board. The Trib’s last such rescue was its acquisition of Hearst’s Herald-American in 1956, which the Trib renamed Chicago’s American and finally remade into Chicago Today. Nobody absorbed the Tribune. When the Chicago Daily Tribune adjusted its name on February 17, 1963, it simply dropped the “Daily” with no great fanfare.

The Colonel’s grandfather, Joseph Medill, became Tribune co-editor and co-owner in 1855, just in time to use the paper to assist in birthing the Republican Party and propelling Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. “Mr. Lincoln and Friends” puts it succinctly:

“Joseph Medill of the Chicago Tribune regarded the President as a kind of personal property, and when his faction seemed not to be securing its share of the patronage he raged: ‘We made Abe and by G- we can unmake him…'” wrote historian David Donald. The Chicago Tribune viewed itself as a founding stockholder in the Illinois Republican Party and as such entitled to regular dividends.

Under the Colonel, the Tribune’s historic Republican cred never wavered. Many people believed George Tagge, Tribune political editor and columnist from 1943 to 1972, “ran the Illinois Republican Party under the auspices of his Tribune position,” as Tribune political reporter and managing editor Richard Ciccone wrote in his Mike Royko biography, “A Life In Print.”

Ever wonder why McCormick Place is “McCormick Place”? Because the shrewd Colonel foresaw the coming need for giant business shows, John McCarron wrote in the Tribune in 1997. “After World War II, McCormick told Tribune Managing Editor W. Don Maxwell to see what could be done about building a convention center on the lakefront. Maxwell, in turn, put veteran political reporter George Tagge on the case.”

As Tagge’s Tribune obituary put it, “As political editor…he was largely responsible for mustering support for and guiding through the Illinois General Assembly a series of bills that culminated in the construction of McCormick Place”.

The original McCormick Place opened by 1960, nicknamed “Tagge’s Temple.”

The Tribune began calling itself “The World’s Greatest Newspaper” by 1895, when the moniker shows up first in the Tribune database in a story headlined “Hoosier Turnip Beats All Creation.” Indiana farmer John Cooper had raised a turnip with a four-foot, 36-inch diameter and seeds the size of garden peas.

If “any of the numerous readers of the world’s greatest newspaper, THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE, doubts the veracity of Mr. Cooper write him and he will mail sample seeds,” the article advised.

After that, “World’s Greatest Newspaper” liberally graced the Trib’s company ads, and they even used the slogan as filler to plug random open spaces in the paper.

To give you an idea of the massive size of the Tribune’s self-regard, consider its special all-Lincoln issue for the centenary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth in 1909. The front page features a single screaming headline across the top of all seven columns:

Lincoln’s name was relegated to a small one-column subhead underneath, and a cartoon title.

“It has been remarked that the Trib conducts itself as though it had won and not coined the slogan on its masthead,” noted John McPhaul in “Deadlines and Monkeyshines.”

So the Tribune never suffered from false modesty. Still, it was Colonel McCormick who slapped the pompous “Greatest” slogan right under the masthead every single day starting August 29, 1911.

About 30 years later, the Colonel added a xenophobic second slogan to the left of the masthead, underneath a waving U.S. flag, on August 7, 1944, two months after D-Day.

The new slogan had already been taken by Hearst’s Chicago Herald-American, not yet in the Tribune stable.

The Tribune added the extra “American” slogan anyway. A Trib editorial declared its hope that the Herald-American wouldn’t mind sharing:

Surely there is ample room for two pro-American newspapers in the city of Chicago. Chicago’s other dailies of general circulation, unfortunately for the people of this city, have no grounds for complaint.

That last bit was the Colonel taking a shot at his three other major rivals in 1944—the Chicago Daily News, the Chicago Daily Times, and the new Chicago Sun, started in 1941 by Marshall Field III to offset the Tribune’s anti-war, anti-federal government vitriol. I’m surprised he didn’t aim at the Defender too, which was cheekily calling itself “World’s Greatest Weekly Newspaper”.

Col. McCormick died in 1955, just four days before Mayor Daley won City Hall for the first time.

Yet decades later the Colonel’s crotchety corpse still sprawled across the pages of the Tribune along with his two slogans. Like a zombie, the Colonel clung tenaciously to life in his paper well into the ‘70s. In print, the Colonel lived at least as long as Mayor Daley, who died in 1976. Mayor Daley died on December 20 that year, while the “World’s Greatest Newspaper” slogan stayed on the Tribune masthead until Dec. 31.

The Colonel was definitely still popping up in 1972. The Trib had only just dropped its “American paper for Americans” slogan on Feb. 6, 1971. The Trib’s coverage of the infamous 1969 pre-dawn raid by police working for Cook County State’s Attorney Ed Hanrahan, which killed Black Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, might as well have been edited by the Colonel himself.

Sample 1972 Colonel sighting: In March, the pinnacle of the mid-20th century plane hijacking and bomb threat craze, someone called Trans World Airlines demanding a ransom to disclose the location of four bombs on TWA planes. Bomb threats against planes were astoundingly common at this time, but for the first time ever, there really were some bombs.

Newspapers exhaustively covered the story:

— the first bomb that was found and defused;

—the second bomb that went off on a grounded jet and blew up the entire cockpit;

—President Nixon’s response;

—the desperate attempt to finally and instantly fix airport security so any goof who felt like it couldn’t get on a grounded plane and plant a bomb;

—and the spate of copycat bomb threats that followed.

The Trib went one better by reporting the bombs might be a worldwide Commie plot: The “swelling chorus” of airline bomb threats “now are regarded by security authorities as opening moves in a broad scale war against the United States commercial air system,” the Trib reported on March 10, 1972. “Analysis suggests the assault is being coordinated by some central group.”

The article gave only one possible “central group,” per “British intelligence sources”: “[C]lasses of air guerillas have been graduating in Cuba and dispatched around the world with the goal in mind of disrupting the non-Communist air transportation systems.”

You never heard about the Communist skyjacker guerrilla flight schools? That’s because it didn’t happen. The Tribune never wrote about it again. Nobody bothered questioning it. As Jerry Ackerman (formerly of Chicago’s American and later the Boston Globe) notes, “Most everyone in the extremely Republican county where I grew up (DuPage) seemed to get the Trib delivered in the morning. It was the giant of its day then as well as now. You knew where Bertie McCormick stood and learned to read your way around it.”

But the Trib’s over-the-top anti-Communism made it anathema to people like veteran Tribune reporter Ron Grossman’s working class, immigrant Jewish family as he grew up in 1940s Albany Park.

And, Grossman adds, “To be Jewish is to be paranoid. We thought because [the Tribune] was so establishment, it must have something in for the Jews.”

“The period after McCormick, until [Clayton Kirkpatrick, editor 1969-79], the paper was still operating as if he was alive,” says Grossman. “The people there, discussing an editorial, someone would say, ‘What would the Colonel say about this?’ Like they needed a Ouija board.”

“The Tribune was a very conservative paper,” explains Michael Miner, columnist and media critic for the Reader for over 40 years, and called “the conscience of Chicago journalism” by former Reader editor Mike Lenehan. In 1972, Miner was a young Sun-Times reporter. “[The Tribune’s] strength was in the suburbs, north shore,” he says. “It was very reactionary. I know we treated it with contempt at the Sun-Times.”

Still, the Colonel’s biggest detractors would have to admit he was an ingenuous businessman with an imagination as big as his ego. This was a guy who didn’t just build a new corporate office building, he launched a worldwide architectural competition with all its attendant free publicity before choosing the design for Tribune Tower.

The Colonel was nutty enough to embed pieces of other historic buildings into his new tower, including everything from the Great Pyramid of Cheops to, even more fancifully, Hamlet’s castle.

The Colonel’s Spelling

The Colonel not only thought English needed to fix its spelling, he thought he could fix it himself and make the rest of the world adapt to his personal spelling choices. In 1934, the Tribune started spelling according to the Colonel. Death only cut back on the Colonel’s spelling decrees. After 1955, the editors reduced the Tribune’s idiosyncratic spelling to a smaller set of words, such as “thru” instead of “through.” The Colonel’s hold on Tribune spelling didn’t break entirely until 1975.

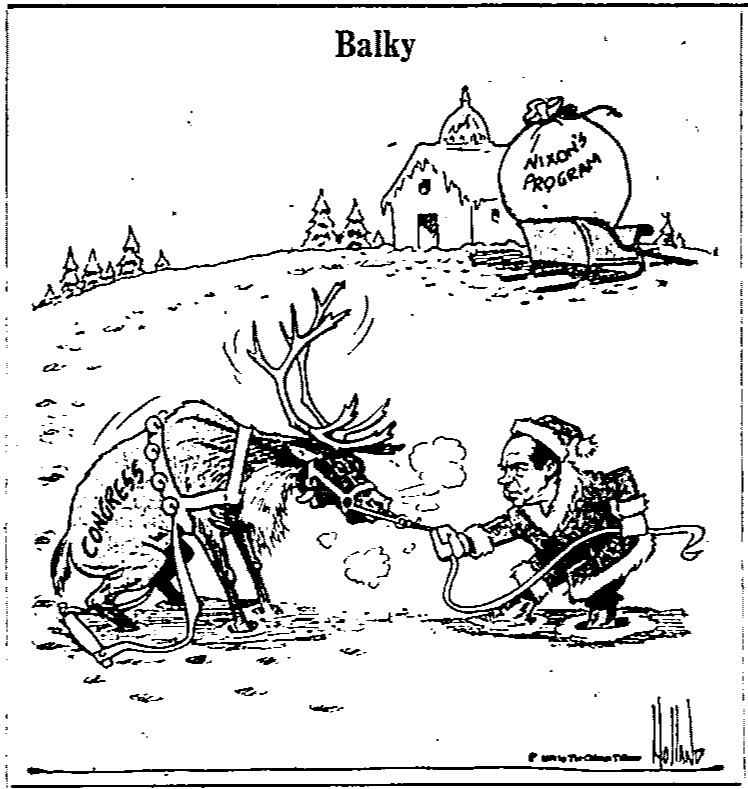

In 1932, Time Magazine wrote with grudging admiration about the Colonel’s pioneering addition of color printing in the daily paper, including a color editorial cartoon smack in the middle of the front page. The cartoons were inevitably, savagely anti-FDR.

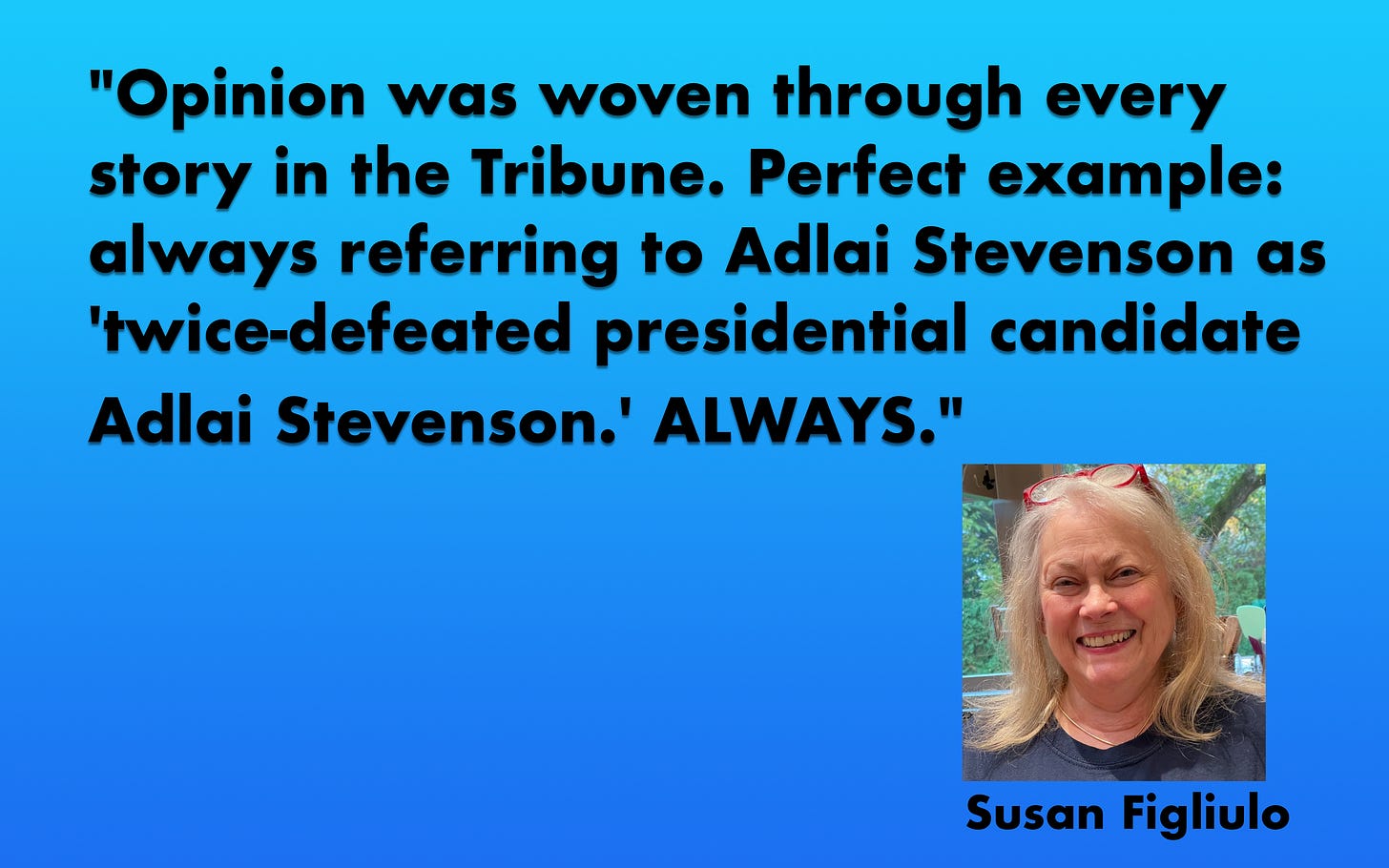

“I thought it was nice to have a cartoon on the front page as well as the ones inside, but couldn’t understand why the front-page ones were never funny while the inside strips always were,” remembers Susan Figliulo, who would join the Sun-Times in 1979 and leave as a copy editor with the diaspora resulting from Rupert Murdoch’s purchase of the paper. Figliulo’s family subscribed to the Daily News, but also got a Tribune most days when her dad brought it home from work.

Eventually, Figliulo says she understood the concept of an editorial cartoon. “And more eventually I thought it was terrible to put opinion right there on the front page.”

The Tribune kept up its front page editorial cartoons until December 22, 1970. Here’s the last one:

You can almost picture Clayton Kirkpatrick walking around Tribune Tower shaking off bits and pieces of the Colonel, brushing slogans and front page editorial cartoons off his shoulders like so much ideological dandruff.

The Daily News

Steve didn’t know the Colonel, dead or alive. His working class city family got the Daily News, though many News readers were middle class, educated and suburban. For a slogan, the Daily News didn’t formally rate itself in relation to the rest of the world’s press. The Daily News variously called itself “The Independent Newspaper,” “An Independent Newspaper,” and “The Complete Evening Newspaper”—that’s their italics.

The Daily News didn’t jump out at you from behind a door yelling about Commies, as the Colonel’s Tribune so loved to do. The Daily News was more like an older uncle, the kind you saw on TV, who wore nice cardigan sweaters with leather patches on the elbows, smoked a pipe, and told you about all the interesting places he’d been. Not that Steve or anyone he knew actually had an uncle like that, but you saw such people on TV.

“The Daily News was the quality newspaper,” says Ron Grossman. “It printed the most literary people. It had no choice because it came out in the middle of the afternoon when there wasn’t much world-shaking news that happened that day at that point, so most pieces commented on yesterday’s news, and they had fabulous coverage of books and the arts. They had to find a niche for themselves, and they did it successfully.”

The Daily News was nearly as old as the Tribune, starting in 1875. More on its history when the News gets its own chapter, but it was always known as the writer’s paper. The Daily News was the Chicago alma mater of people like Ben Hecht of “The Front Page” fame, and printed the 1921-22 columns gathered in his book “1001 Afternoons in Chicago.”

“The Daily News was much more of a global paper, it still had foreign bureaus, it had a correspondent in Vietnam,” says Mike Miner. “The writing had a greater sense of elegance. You had a columnist like Sydney J. Harris who pontificated. We didn’t have anybody who pontificated at the Sun-Times…. [The Sun-Times] was younger and scrappier, it wasn’t as deep.”

The Daily News international coverage was second to none by many estimates, even at the end. Only the New York Times had more foreign correspondents, and as Richard Ciccone points out in his Royko biography, the Daily News supported “more than the other three Chicago papers combined.”

“According to Jaci Cole and John Maxwell Hamilton’s “A Natural History of Foreign Correspondence: A Study of the Chicago Daily News, 1900-1921,” the Daily News “virtually invented the ideal of a quality, professional American foreign news service.”

When the Daily News gasped its final breath in 1978, its writers had won 15 Pulitzer Prizes.

But the Age of Newspapers was already fading in 1972. Radio, then television, and spanking new expressways without any potholes yet rolling out during the ‘50s and ‘60s toward the burgeoning suburbs—all took their bites out of newspaper readership. You didn’t read a newspaper on the way to work if you were driving a car instead of taking the train or streetcar.

Afternoon papers were dying most quickly, for exactly the reason Ron Grossman highlighted above.

Even with extra editions, the afternoon paper was at an instant disadvantage. You could put out an extra street edition, but that’s not the paper you delivered to your subscribers. That paper got thrown on your porch in the late afternoon by a paperboy, which means it had to be written, typeset, printed and distributed much earlier. And only so many big news stories happened in the morning with time left to write, typeset, print and deliver. Afternoon papers like the Daily News already faced the problem all newspapers would confront with the internet in the 21st century—how to make old news relevant.

That’s why the Daily News moved from its gorgeous Art Deco headquarters on Canal between Madison and Washington—now 2 Riverside Plaza—and into the Sun-Times building after Marshall Field bought the paper.

“The Daily News was, then and until it folded in ‘78, was really revered as the immigrant’s paper,” says Rick Kogan, who would work for the News, the Sun-Times, and finally go to the Tribune in 1985. Kogan recalls one particular Polish immigrant reader he met on the Daily News’ last day:

“I’ll never forget the day the Daily News folded, I was taking a cab down to play I don’t know, fuckin’ racquet ball, with some friend from the paper. I’m in the cab, and the guy is a very deferential cab driver. I obviously said the Daily News building, and he’s driving down, and he goes, ‘I understand there won’t BE a Daily News tomorrow.’ And I said that’s true, as of tomorrow, Saturday’s the last edition. And he doesn’t say another word.

“He goes pulling into the delivery dock. I’m fumbling around for my money and he gets out and comes around and opens the door, and he’s crying. An older guy. He says, ‘Sir, I hope you work for the Sun-Times.’ I said no, I work for the Daily News. That’s OK, I’m fuckin’ 26 years old. And he goes, ‘I learned to speak English from reading that newspaper.’

Oh my God. And he was refusing to take my money.”

Reading the Daily News in the ‘60s and ‘70s didn’t necessarily make you liberal as the word would be defined today. Many hardcore lefties of the time sneered at the idea that the Daily News was “the ‘liberal’ paper.” Still, the News had enough comparatively liberal moments in the 20th century to earn the term back then.

Take the Daily News coverage of Chicago’s week-long race riot in 1919. Tensions were high in a broiling summer long before air conditioning. The city’s Black population had grown by almost 150% in the previous decade, most of it after 1915 with the start of the First Great Migration out of the Jim Crow South. Race relations, as we know, had not kept pace. African-Americans fleeing Southern racism merely found new forms in the North.

Seven days of rioting followed the death of Eugene Williams, a Black teenager who accidentally drifted into a whites-only beach area while swimming in Lake Michigan. Some white swimmers threw rocks at Williams, who drowned, but police refused to arrest anyone. Twenty-three Black Chicagoans and 15 whites were killed; 342 Blacks and 195 whites were injured.

The Daily News assigned reporter Carl Sandburg to write a series of articles on the riot and Chicago’s new Black community, collected into a book the same year. The Daily News didn’t have a Black reporter in 1919—its first Black reporters would be Les Brownlee in 1952 and Burleigh Hines in the early ‘60s—but it did understand that the deadly riot, and the Black community, deserved a full, comprehensive analysis. Sandburg’s series fully covered the role of bands of whites from South Side neighborhoods who invaded the nascent “Black Belt” to attack Blacks.

And that’s right, Carl Sandburg, Mr. “City of Big Shoulders” himself, was a Daily News reporter.

In the ‘60s and ‘70s, the Daily News was liberal in that it published things like Mike Royko’s unflinching coverage of civil rights issues, both in the South and in Chicago. And editor Larry Fanning (and successors) ignored complaints from the circulation department about outraged readers cancelling subscriptions.

“A man named Ken Johnson who was head of the Daily News circulation used to storm up into Fanning’s office about twice a week to complain about Mike’s columns,” Lois Wille told Richard Ciccone for his Royko biography, “A Life In Print.” “In the newsroom we were all so proud of what he was writing and what the paper was doing, but in the circulation department they were angry.” At home, Mike Royko got a brick through his window.

Studs Terkel subscribed to the Daily News. It may be necessary for some younger readers especially to explain the significance of Studs’ subscription.

You didn’t get much more lefty than Studs Terkel in Chicago back then. Son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Studs grew up during the Depression in his family’s boardinghouse at the gritty intersection of Wells and Grand, mingling with every possible Chicago character before he got to high school.

By 1972, Studs was already well into his 45 years of daily interviews on Chicago’s classical radio station, WFMT. He landed there after losing his short-lived TV show on NBC in the ‘50s—thanks to his tirelessly radical views. When Studs’ Place made the leap from local television to the NBC national network, a troubled NBC executive came out from New York and asked Studs if he’d signed some petitions—anti-poll tax, anti-lynching, anti-Jim Crow petitions. “And I said, ‘Yeah,’” Studs recalled later. “I said, ‘In fact, I never met a petition I didn’t like.’”

Result: Studs was off TV, but on his way to becoming a human Chicago landmark and winning a Pulitzer Prize for his 1985 oral history of the World War II, “The Good War,” another in his seminal books of interviews with common people that started with “Division Street America” in 1967.

Studs criticized the Daily News too whenever he thought the paper deserved it, which of course it did because no newspaper was, is, or ever will be perfect. But Studs still called the Daily News “the city’s most enlightened” newspaper.

A Daily News on your front porch meant, at the very least, that you were less inclined than Colonel McCormick to see communists hiding behind every evergreen bush when you opened the front door and stepped out to get your newspaper.

TIME’S ALMOST UP TO WIN COOL 1972 STUFF BY SUBSCRIBING FOR FREE! Contest ends when Chapter Four drops this month. See full list of prizes HERE.

The Daily News and Mike Royko

In this world of newspapers, Steve spent his formative years with his family’s paper, the Daily News. He spent more time with the Daily News, and had a more intimate relationship with the News, than he did with many of his relatives.

“In your time frame, Mike was central to that,” says Rick Kogan of the personal relationship readers formed with their newspapers back in the day.

Steve’s family read Mike Royko in a long thin column of type running along the inside crease on page 3 of the Daily News. They read Mike’s column from its first appearance in 1963 in the op-ed pages, to his jump to page 3 in 1966, and there until the paper folded in 1978.

Next they read Mike in his new home at the Sun-Times--on page 2, with a bigger picture, in two wider columns stuffed into a square box with a black frame around it. That went on until vile Australian media magnate Rupert Murdoch bought the Sun-Times in 1984. Then Mike quit, figuratively carrying his typewriter out of the short, ugly Sun-Times building that squatted on the north bank of the Chicago River at Wabash, and walking across Michigan Avenue to the tall, stately Tribune Tower.

In the Tribune, Mike smirked once again over a familiar long thin column of type on the inside crease of page 3. That, at least, made the otherwise dizzying change in altitude feel more familiar to Mike’s legion of long-time readers.

For literally all of Steve’s life, getting the Daily News meant getting Mike Royko. At the Bertolucci’s, “Where’s Royko?” and “Where’s the paper?” asked the same question. Nothing was more disappointing than flipping to page 3 in the Daily News and seeing the brief message “Mike Royko is on vacation” instead of Mike’s signature smirk above his column.

There wasn’t a single day in Steve’s childhood when he didn’t go to the kitchen for a glass of milk or 50/50 and see a Mike Royko column fluttering under a magnet on the refrigerator door. Two columns stayed there longest, published just days apart in April 1968, when Steve was six. His mom pinned those columns side-by-side near the top of the frig, so Steve didn’t notice them there until he was over four feet, in early 1972.

The first column was “LBJ Deserved a Better Fate.” I already mentioned this column in Chapter 3, because I was reading it on a microfilm machine when Gil walked up one day. I looked up this column on microfilm to see it the same way Steve saw it on the refrigerator door, or as close as I could get.

As he read, 10-year-old Steve understood the column was about somebody who was president, and decided not to run for re-election. He dimly realized for the first time that Richard Nixon had not been president forever.

“The president of the United States told the people of the United States they are so divided against themselves he dares not take part in a political campaign for fear that it could get even worse,” Mike wrote in 1968. Then he described how everybody hated LBJ. “Every smart punk grabbed a sign and accused him of being in a class with Hitler or mass-murderer Richard Speck….Maybe he wasn’t the best president we might have had. But we sure as hell aren’t the best people a president has ever had.”

Steve didn’t remember this LBJ guy, but he sure felt sorry for him.

The other column, to Steve’s eyes, was about another man with three names, Martin Luther King. This man had been shot by somebody, murdered in cold blood, and Mike wrote that it didn’t matter if the FBI found the guy who pulled the trigger: “They can’t catch everybody, and Martin Luther King was executed by a firing squad that numbered in the millions.”

This was the scariest thing Steve had ever read, worse than The Exorcist. Mike said everybody had killed Martin Luther King, so didn’t that include everyone Steve knew? He’d never thought his mom, his dad, brothers or neighbors would kill someone. His Nona often wanted to kill one of Steve’s five older brothers, but she wasn’t strong enough to commit murder with the closest wooden kitchen spoon, and her deadly rages always subsided before she could find a better weapon.

Ten-year-old Steve reread that paragraph again to make sure he’d gotten it right. Everybody shot Martin Luther King? Yes, Mike said “everybody.” It was an idea that was hard to shake, like a really good episode of The Twilight Zone viewed just before bedtime.

Steve read on.

“So we killed him. Just as we killed Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy,” wrote Mike. “No other country kills so many of its best people.”

The Daily News wasn’t “liberal” enough to satisfy the 21st century, but it was liberal enough to let Mike Royko tell its readers they were as much to blame for the state of the world as anybody, even the country’s worst assassinations.

Often Steve had no idea what Mike Royko was talking about, or what the Daily News front page stories meant. But he always read the paper, and he always read Royko, anyway.

The Sun-Times

If the Daily News was a smart uncle in a cardigan sweater smoking a pipe, who was the Sun-Times? Maybe it was your scrappy aunt who worked her way through college and always wanted to talk politics.

As we mentioned earlier, Marshall Field III founded the Chicago Sun in 1941 to counter Colonel McCormick’s ferociously anti-World War II, anti-FDR Tribune. (The Colonel, we should note, turned on a dime and ferociously supported World War II once it started.)

The Sun merged with the Chicago Daily Times in 1948. The Daily Times was also a tabloid, also scrappy, and called itself “Chicago’s Picture Newspaper.” It featured relatively short, snappy stories, lots of pictures, and an entire centerfold every day of huge news photos. The Sun and the Daily Times were tabloids, by the way, but they were huge tabloids, practically the size of a broadsheet.

The Sun-Times claim to being the oldest paper in town stems from the Times, which was launched by the owner of the Chicago Daily Journal in 1929, the same year the Journal closed. I see competing claims on whether the Chicago Daily Illustrated Times was merely a relaunch of the conservative broadsheet Chicago Daily Journal as a completely different paper, or whether the Journal’s owner sold its assets and created a new paper in the Times. I’ll see if I can nail that down.

And for the coming Sun-Times chapter, we’ll spend some fun time looking inside the Sun and the Times.

“The Daily News wasn’t editorially I don’t think as liberal as the Sun-Times was,” says Rick Kogan. “The Sun-Times was the liberal alternative to the Tribune.”

“Liberal,” of course, is still a relative term—the Sun-Times endorsed Nixon in 1968. And in 1971, the Sun-Times endorsed Mayor Daley over Republican opponent Richard Friedman, leading to a protest letter by the staff. Friedman “was Republican in name only,” explains Mike Miner.

“The Daily News in its psyche had two rivals, the Sun-Times and the Tribune,” John McCormick wrote me in an email. “The Sun-Times was indeed the bright(er) one of those two but as a tabloid with effete editors and a scrappy local staff, it wasn’t sure what it wanted to be – some days it was a faux NYT, all powdered and serious; other days it was a scandal sheet with some wonderful yarn about public corruption.”

“The Sun-Times was certainly the paper of choice back then,” says Mike Miner. “It was a very vital paper. And it was a morning paper, so people read it (on the way to work)…..We were a better paper probably than we needed to be. [Editor Jim] Hoge at heart wasn’t a tabloid editor. He wound up running Foreign Affairs magazine.”

Who read the Sun-Times? Bob Hartley, that’s who. In one episode of the beloved ‘70s sitcom The Bob Newhart Show, psychologist Bob Hartley gets home from work and reads the Sun-Times in his lakefront highrise condo at 5901 N. Sheridan.

It’s the episode where Bob patronizingly mentions to his wife Emily, a teacher, that he has four more years of college education than she does. Later Bob finds out, to his consternation, that his IQ is only 129, compared to Emily’s 151. We don’t know for sure what paper Emily read. I’m betting the Daily News.

Like any Sun-Times reader, Dr. Bob Hartley probably wanted a shorter read, easy to handle in close quarters during a commute on mass transportation. The Sun-Times was a compact tabloid, unlike the large broadsheet Tribune and Daily News. Bob read the paper on the L on his way home from work, as all observant Bob Newhart viewers know from the show’s opening credits.

Presumably Bob stopped at a newsstand on his way to the L and picked up a late edition of the Sun-Times, although this is not shown in the credits.

If you want an idea of how hard it would have been for Bob to read the Tribune or Daily News on the L, watch Buster Keaton in “The High Sign.” Go ahead—the newspaper scene is right at the beginning, it won’t take a moment.

Chicago novelist Nelson Algren, winner of the very first National Book Award for “The Man With The Golden Arm,” read the Sun-Times in the ‘50s, according to his friend renowned photographer Art Shay. Algren was living in a tiny apartment at 1523 W. Wabansia without a shower back then, using the Division Street YMCA to bathe. That worked out fine until he began an affair with French existentialist, novelist and feminist Simone de Beauvoir. Shay recalled later that Algren called him up one day when Simone was visiting and said, “Just tried to get Frenchy into the Division Street Y to bathe, but they turned us down just because she doesn’t have a dick.” Shay wrote that he could hear Simone de Beauvoir saying “Merde!”, “then playfully swatting Nelson on the head with his Sun-Times.”

Algren must have read the Daily News also, or added it to his reading later, since he called up Studs Terkel and told him to read new columnist Mike Royko. “That was something coming from Algren,” Terkel recalled later. “He hated newspaper people.” Later, Algren and Royko would become mutually admiring pals.

Ron Grossman’s family read the Sun-Times and its predecessors. In the early ‘70s, he says, “The pecking order among journalists would be roughly a birth at the Sun-Times, with the Tribune below that. You know the old Riccardo’s restaurant. It was the Friday night gathering place for people in the business. So the most respected people were those from the Sun-Times.”

Why?

“Because they quite correctly thought the Sun-Times reported politics more fairly than the Tribune did.”

Chicago Today

Chicago Today is the Rodney Dangerfield of 1972 Chicago papers, but not just because it gets no respect. Chicago Today was also colorful, often hilarious, and edgy.

Take Chicago Today’s “public service” column, Action Line, which solved reader problems. The Daily News, for instance, had Bee Line. But you’d never read this in Bee Line—from Action Line on February 7, 1972:

The letter:

My wife divorced me in July of 1968, receiving everything from the kids to my clothes. She also agreed to pay the lawyer. I now plan on remarrying, but my ex-wife insists the divorce never went thru. Her lawyer, tho, told me that it was finalized and wants $250 from me for a copy of the papers…She took me to the cleaners as it was, as I walked out with only the clothes on my back. Having the papers would put my mind at ease. Can you get them for me? --R.L.

ACTION LINE:

No way. The attorney didn’t mince any words. Replying to your statement, ‘I walked out with only the clothes on my back,’ he said he didn’t believe you owned anything else. Furthermore, he claims you left a wife with two children, and that for three years you have given neither her nor the youngsters any support money, leaving her with no alternative but to go on welfare. ‘I never pushed your former wife for the attorney’s fees since I don’t mind giving charity to those who deserve it,’ he said. ‘You are neither deserving of charity nor would I give you any.’ The lawyer closed by telling us he’s going to advise your former wife to petition the court to set child support, alimony, and his fees.

Recall that the Tribune bought Chicago’s Hearst paper, the afternoon Herald-American, and renamed it “Chicago’s American” in 1956. Hearst papers were notorious for covering scandal, blood and guts. Think of the worst possible New York Post issue you’ve ever seen, then imagine something far worse because strangely, in a world where movie stars could barely kiss onscreen, some newspapers lived on scandal.

Naturally the American settled down considerably after the Trib got hold of it, what with the conservative Colonel less than a year in his grave and still surprisingly feisty.

But the American’s reputation lingered. After all, the American did, by definition, have a big capital “A” pinned to its chest, even if the letter was black ink instead of scarlet. And most of the old rapscallion Hearst staff remained.

Here’s an assessment in the Chicago Journalism Review, by Lewis Z. Koch, of the American and its progeny Chicago Today in 1970—a year and a half after Chicago Today’s birth:

Chicago Today is a bastard. Its mother, the American, was the cheapest whore in town, bending over backwards to titillate all comers at a nickel a throw. So when she took up with the Chicago Tribune, that grand old man in high starched collar and waistcoat, there were knowing chuckles and smirks all over Chicago. Any offspring produced by that pair had to be illegitimate, no matter how many times they changed its name or dressed it up.

“'Today and American were both very thin,” says Rick Kogan. “The American wasn’t given anywhere near the resources it needed….I have never, ever found anyone who said ‘Oh my God do I miss the American.’…. Nobody in the world ever applied to Chicago Today first.”

“I don’t know that I ever heard someone mention it as a rival,” says John McCormick. “Today was like a gnat, buzzing around but not accomplishing much. The staff was seen as the Tribune’s Double A team – lots of people on their way up to the big leagues or on their way down…..I never knew who Today’s readers were…..You could go a full year in Chicago journalism without once having someone ask, ‘Hey, did you see that story about (fill in the blank) in Chicago Today?’”

Jerry Ackerman landed at Chicago’s American as a lobster shift re-write man in 1963, not long out of Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, thanks to legendary (sometimes infamous) Medill Professor Dick Hainey. Hainey was a Tribune editor charged with cleaning up the American enough to let it in the Tribune’s house, or, more accurately, next door to the Tribune’s house.

Ackerman would move to Boston and a distinguished 30-year career at the Boston Globe, including a shared Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. But in 1963, he showed up for his first lobster shift the day John F. Kennedy was shot. “They didn’t know what to do with me,” he says now. “I was sort of dazzled and befuddled and they didn’t know I existed, so that worked out fine.”

In 1963, Ackerman recalls, “The American had a 430,000 circulation. It was #4 of four papers, even though it was eighth largest paper in the U.S. But it was a midget in Chicago, so when the Tribune acquired it, they let it run as it was, then made it more intellectually upscale. They had New York Times rights, so they let the American use the New York Times wire and we used it a lot for our international coverage--we had no foreign correspondents. And so on the one hand we were trying to appeal to the academic audience a little bit, but we still were big on covering what the syndicate was up to, who was found stuffed in a trunk, crime in City Hall. So we were still of that Hearst mentality, but we dressed it up a little bit.”

From Ackerman’s description, John McCormick’s confusion about the paper makes perfect sense. After the Tribune bought it and changed the name, Chicago’s American didn't really know who it was anymore, or who it was for. If the Daily News was your interesting uncle in the cardigan sweater, and the Sun-Times was your scrappy working political aunt, Chicago’s American/Chicago Today was more like your cousin raised by wolves, suddenly rescued from the wilderness, and gingerly brought back into human society. Chicago’s American/Today was learning to use silverware, and you never knew if it might stab you with the fork just to see what happened.

“Not in my household,” says Ron Grossman at the idea of the Herald-American or Chicago’s American in his family’s Albany Park home. “My parents would never have that in the house.”

“The Herald-American was like the king of vulgar newspapering,” says Grossman. “William Randolph Hearst was pumping for the European fascists. He also saw communists under every bed and exploited that. But he had a sense of, you gotta have gimmicks to sell newspaper, so they had a constant array of contests going on. They were vulgar in the sense of appealing to the lowest common denominator of reader.”

The Chicago Journalism Review concluded that Chicago Today was turning out “some of the best writing this town has seen” as well as “some of the most godawful stories Chicagoans have ever had the misfortune to read.”

Mary Knoblauch started at Chicago’s American while she was at Northwestern in 1963, and left the Tribune after 40 years. She went from a departmental secretary for the society page, to film reviewing and entertainment editor, to editor of the Sunday Tribune Magazine, and everything in between. She remembers the passion for writing at the American/Today, and the fun of joining the team to transform Chicago’s American into Chicago Today.

“We were kind of suspicious they actually just used us as a lab, the Tribune, to see what you could do and when you could do it,” says Knoblauch. “They saw papers were going the same way of all flesh, and the Tribune was so stodgy. So they experimented with Today to see where they wanted to go with the Tribune. It was such fun.”

The writing at Chicago Today could be extraordinary, with staffers like Michael Hirsley, Kenan Heise, and Jeff Lyon. As per Mike Miner’s quote at the start of this section, they and others went on to illustrious careers with the Tribune after Today folded. TV critic Bruce Vilanch would go on to become a Hollywood writer and bona fide celebrity via Hollywood Squares. It’s possible you don’t know Vilanch’s name, but you’ve heard his jokes on the Oscars and a zillion other places. And I bet you’ll recognize him.

A scrumptious Chicago Today ‘72 sample from each before we go on.

From Michael Hirsley’s both panoramic and intimate February 1 account of Mahalia Jackson’s wake:

The queen of gospel singers lay still in a powder blue lace gown.

Above her coffin, in the octagonal dome of the Greater Salem Baptist Church, 63 plain light bulbs shone. One had burned out.

Double lines of visitors jammed the sidewalk east and west of the church entrance at 215 W. 71st St last night, the entire block from Wentworth Avenue to Yale Avenue and a half block south on Yale.

Altho there was no loud sobbing, and there was organ playing and a soloist singing, those coming in the door walked quietly and slightly bent as they serpentined, single file among the crowd which had found pews or standing room.

As the soloist finished, there was light applause.

Dr. Morris H. Tymes, pastor of the Greater Mount Moriah Baptist Church, 214 E. 50th, stood at the lectern above the coffin.

As the people filed past below him, pausing briefly and looking sadly into the coffin, Dr. Tymes’ first words seemed loud and harsh.

“There is nothing wrong with clapping your hands,” he said. “This is not a sad occasion.” There were a few hands clapping and scattered murmurs.

“We should be happy,” he said. “Mahalia has won the victory.” Now there was response, clapping and “Amen.”

“We’re black people and we’re emotional,” he said. “Clap your hands! Clap your hands!”

From Jeff Lyon’s urban opera of a crime story on March 3, covering the death of an Ohio doctor in the big city for a convention who winds up dead in a bad part of town:

The street is like a peddler. It jangles and clangs its wares--girls, pretty young men, strippers, cheap whiskey--all at inflated prices.

It hawks its products with girls shimmying behind shades, starbursts of lights, the loud voice of the barker, the soft whisper of “You want a little company, honey?”

But beneath the commercial veneer Rush Street has a code, like any peddler--you take what you can and leave the customer something. Or you run out of customers.

If anyone except Dr. Joseph K. Welborn knows what happened to him about midnight Wednesday, they aren’t talking. The Toledo surgeon was found early yesterday, face down in a narrow gangway between 930 and 932 N. Rush St.

And from Bruce Vilanch’s March 3 column—remember what I said about how you never knew when Chicago Today might stab you with a fork?

CBS unveiled its most dramatic program change in 20 years yesterday and you’re reading it first in CHICAGO TODAY.

“All in the Damned,” a situation holocaust, will premiere this September in an unprecedented scheduling move. The series will wipe out the entire Monday and Tuesday lineups on the network, beginning at 6:30 p.m. and running for six hours….

The show…will star Lucille Ball and Broderick Crawford as the heads of a powerful German dynasty, the Von Essenschlepp family, who singlehandedly forged Germany’s destiny, and many of its Volkswagens, before World War II.

Other continuing characters in the series are Bill Bixby, as Marlene, an ambisexual chairman of the Von Essenschlepp board of directors…and Liza Minnelli, as a decadent American with green fingernails.

….In the first episode, ‘Here’s Luchhhy,’ Frau Von Eseenschlepp is disturbed when she gives birth to quintuplets, all of who are blonde, blue-eyed, angelic and have eyes that focus on airplanes and make them tumble from the skies in flames.

….Naturally, an undertaking of such scope and, may I say, enormity, staggers the mind. In doing away with such mundane, everyday dramatic literature as characterization, plot, nuance and negotiable storyline, CBS is certainly striking a blow for free-form art on television. But it’s nothing they haven’t tried before, especially in their editing of films for television, and with more devastating effect.

Chicago’s American/Chicago Today was probably the most fun paper to read, and definitely the most fun to work for. Young reporters like Jerry Ackerman and Mary Knoblauch got to rub elbows with actual Front Page newsmen, including legendary Harry “Romy” Romanoff, a man so much a character that a 1950 TV show did an episode on him, titled “Harry Romanoff, Chicago Reporter.”

Time Magazine wrote of Romy in 1969, just after he’d retired:

His reporters tell, for instance, the time in 1966 when Richard Speck was accused of murdering eight nurses (missing only Corazon Amurao, a Filipina). Romy assumed an accent and began phoning around town as the Philippine consul. For a follow-up story, Romy decided to dig up details of the accused man's marriage and troubled early life. He got the phone number of Speck's mother, called and identified himself as Speck's attorney. Speck's sister began talking, and Romy got his story. He once observed: "They said I constantly posed for somebody else. It's not my fault if they misunderstand."

Oh, we’ll have a good time with the Chicago Today chapter to come. More Romy stories, among other colorful characters. And I should save Jerry Ackerman’s description of the sunrise in the Chicago’s American newsroom for that chapter, but I can’t stop myself from including it now. Perhaps I’ll repeat it, because this scene is, frankly, beautiful.

Picture the surely grimy newsroom on the fourth floor of the WGN Building—rear, not on Michigan Avenue—and the sunrise outside its windows.

Jerry Ackerman’s Sunrise Story

And then there was the ritual of the sunrise. There were no buildings between us and the lake. The building was at the corner of Illinois and Michigan Avenue. The newsroom windows faced due east. We were on the fourth floor, no buildings to obscure the view. And every once in a while there’d be a terrific sunrise.

And the ritual was, all work would stop. People would pivot in their swivel chairs. The copy desk faced straight out the east window. There were about four copy editors, and half a dozen people in for sports by then, with the first edition going out at seven.

And all work would stop. And the room would be silent, and we just sort of had meditation on the sunrise.

And the silence would be broken by a veteran copy editor named Jim McCormick. He’d been there for years, and he would pop his lunch bag, a paper bag. And it was back to work.

Chicago Daily Defender

Of the major dailies, Black Roselanders would have most likely read the Sun-Times in 1972, known for the biggest Black readership of the larger papers.

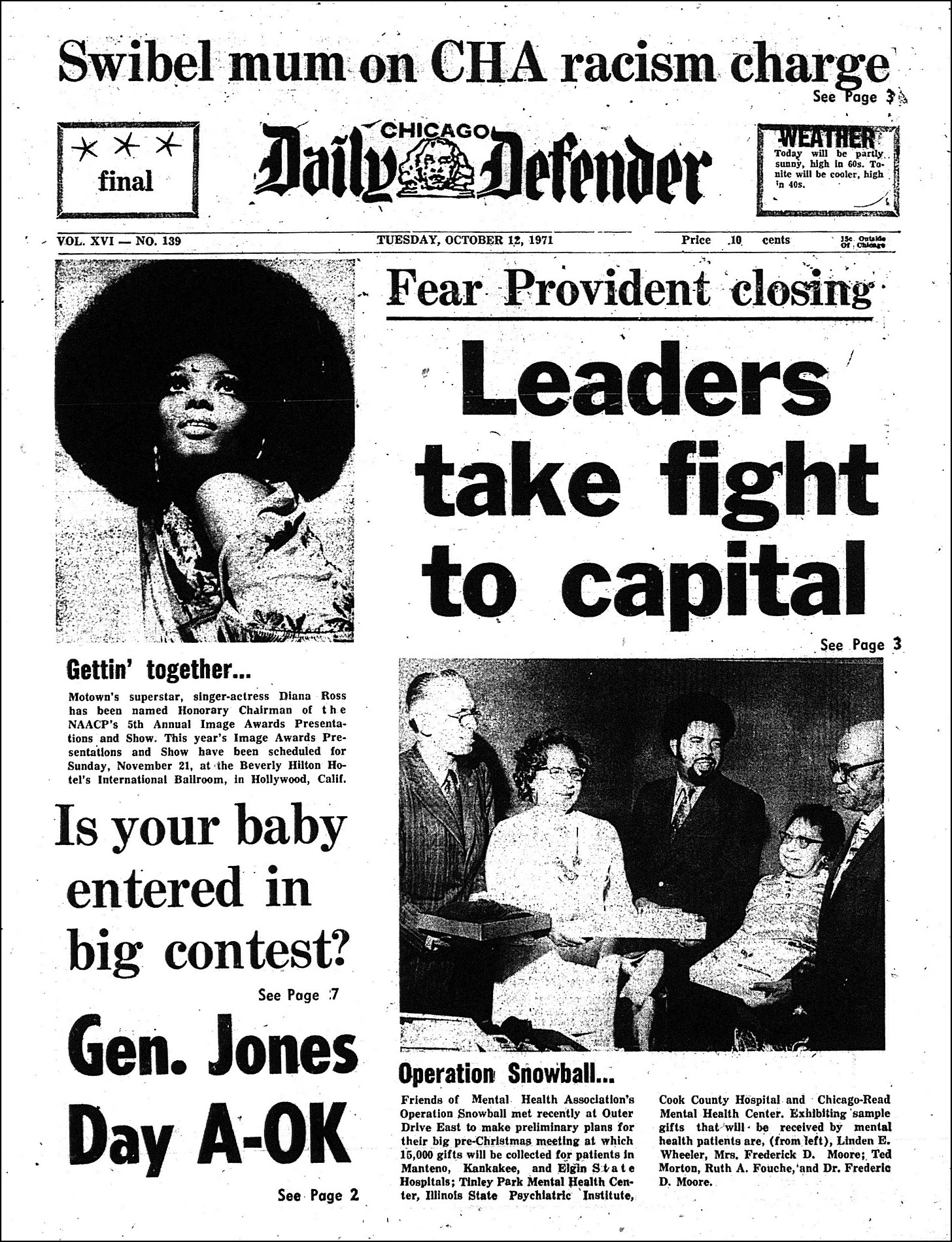

But first, they surely read the legendary Chicago Defender.

The Defender was founded in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott and grew into the largest Black newspaper in the country, reaching an estimated half million readers each week nationally as every precious copy got passed among many hands. Black Pullman porters acted as the paper’s de facto distributors in the South, where white distribution companies wouldn’t touch it.

In a classic Chicago and American story, Robert Abbott set his sights on Chicago after visiting the 1893 Columbian Exposition, where he met Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells. Both would inspire Abbott to turn to journalism and activism after he found racism stifled other career paths.

This is the 1964 masthead, from the front page included in the 1972 Newspaper Medley at the top of the post.

I haven’t been able to get a physical copy of the paper closer to 1972 for photographing. The basic design of the paper was quite similar in ‘72, but it’s nice to see the real thing. For now, here’s a representative front page from microfilm:

The Defender fearlessly exposed the lynching and other Jim Crow atrocities of the South, simultaneously promoting the North and Chicago to its readers. More than a newspaper, the Defender was a vehicle for history-making change by spurring the first and second Great Migrations of Blacks to the North.

Abbott’s nephew John H. Sengstacke succeeded him in 1940. Under Sengstacke, the Defender made the jump to a daily paper—the second Black-owned daily newspaper in the country, and the largest. Ethan Michaeli’s definitive “The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America” describes that day:

On Sunday, February 6, 1956, after months of discussions, plans, revisions, and trial and error, the first edition of the Daily Defender was finally ready to roll. John Sengstacke splashed champagne over the sheets of blank newsprint and then lifted up his youngest son, six-year-old Lewis, to press the button starting the massive presses. Within a few minutes, the first copies of the new paper emerged, a twenty-four page tabloid with large black-and-white photos on the front cover and sports on the back, selling for five cents a copy. It was nearly midnight, far later than had been scheduled, but there was still just enough time to get the newspaper out on the streets for the morning delivery.

Illustrious writers? You can’t ask for more than Langston Hughes and Gwendolyn Brooks. Let’s read a Defender sample from both.

Here is what appears to be the earliest Gwendolyn Brooks appearance in the Defender, in a section entitled “Lights and Shadows A Little Bit of Everything’” in 1934:

Oh, who shall force the brave and brilliant down?

There's no descent for him who treads the stars.

What shall he care for mortal hate or frown?

He shall not care, his bright soul knows no bars.

Take his weak frame and twist it to your will.

Strive to discourage and to make him fall;

Oh, make him suffer! Cause his tears! But still

Shall not his spirit rise and vanquish all?

What things the Power buried in the skies

Of man's attempt to bruise and hinder man?

What pity has that Force for our poor cries,

When crude destruction is our foremost plan?

GWENDOLYN BROOKSLangston Hughes wrote a column called “Langston Hughes Says.” Here’s one from 1965, “On Angel Equality,” an entry in his continuing series of conversations with the fictional Jesse B. Simple of Lenox Ave. in Harlem. Here, Simple talks to Hughes about the recent death of his friend Boddidly, who was younger than Simple, which troubles Simple. They segue into a discussion of how different words have changed meaning, like “disturbed” now meaning “crazy.”

“Sometimes I think I am going crazy myself.”

“Over what?” I asked.

“Over not being able to solve the race problems,” declared Simple. “I have been studying it ever since I been black—and it still disturbs me.”

“How a man of your habits and beer drinking facilities can expect to go to heaven, I do not know,” I said.

“I am always ready to meet my Maker,” declared Simple…."Let us drink now to Boddidly who is gone from our midst this evening. He was a good man who tried to do right, but often slipped by the wayside and backslid on the road, and I doubt if tonight he is washed whiter than snow.”

“Do you mean to say that you think Boddidly might have gone to hell?”

“He may be,” said Simple, “but I hope not, because if Bo has gone to hell, he will be sure to meet Mack down there. Him and Mack was mortal enemies all up and down Lenox Ave. If they meet in hell, they would sure start a fight and I do not want Negroes disgracing themselves in front of the Devil.”

….”I once heard you say that Negroes have as much right to be wrong as anybody else,” I argued.

“Not when you’re an angel,” said Simple.

Because the Defender was in a way a community elder as well as a newspaper, you might say that in our continuing family metaphor, the Defender was your wise but fun grandparent, who wants the best for you and wants you to do your best.

And yes, a fun grandparent—the Defender started the first children’s newspaper page, which grew into the extravaganza that is the annual Bud Billiken Parade.

By 1972, the Defender focused most on Chicago’s Black community and the different racism of the North. Typical ‘72 issues cover Bronzeville like the small town it was, spotlighting high school events and gospel choirs, while also relentlessly pursuing stories like suspicious shootings of Black men by police, and the activities and politics of Black activists and organizations, such as the Rev. Jesse Jackson and his split from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and subsequent founding of PUSH.

The 1972 Defender is also a great read, with endlessly fascinating columns like the Walter Winchell-style “Charlie Cherokee Says”—which began in the ‘40s, written by a member of FDR’s “Black Cabinet”—and “Doc Young’s Good Morning Sports!”

See THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, the January 4 entry, for more on the history of Charlie Cherokee Says, which I will continue to pursue. See the February 10, 1972 Charlie Cherokee Says for an item that kicks off a Chicago history expedition. More Charlie here under December 29, 1972; here under January 25, 1972 for Charlie’s look at Shirley Chisholm, Jack Brickhouse and Wendell Smith; here under December 14 for Charlie’s take on the Jesse Jackson/Ralph Abernathy feud; and here under February 2 for Charlie on Jesse Jackson’s handshake with President Nixon.

And yes Younger Readers, the Defender ran a political/society column titled “Charlie Cherokee Says.” It’s 1972, Jake.

The 1972 letters section can be especially moving. This one, from October 1972, I want to present in its original typeface, since reading in the closest form to the original is, to me, always more satisfying:

Unfortunately, the Defender was affected by the same media trends as every newspaper, and in addition, lost some readership once Black Chicagoans saw themselves represented more in other publications. The Defender was forced to reduce to weekly editions in 2008, and went entirely digital in 2019.

At last, HOPE SPRINGS for Chapter 4.

thanks for the fine detailed piece on history Chicago papers. I grew up with the Tribune-we had it delivered. My Dad took the train downtown to work and he bought a paper on his way down, tossed it and bought the Daily News at some point and bought the evening edition on his way home and sometimes brought it home. I was much older when I realized who read which newspaper and why. While I always dislike and disagreed with the conservative voice of the Tribune, I always liked the coverage of cultural events in the city and later enjoyed many of the less than conservative voices of other writers. Thanks again, I plan to reread the piece later.