THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972: Political tabs of many kinds come due

July 24-30, 1972

To access all website contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 is part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. Follow THIS CRAZY DAY on Twitter, @RoselandChi1972.

July 24, 1972

Chicago Today

Like Mike Royko—who eventually replaced him at the Daily News—Chicago Today’s star columnist Jack Mabley does occasional columns of reader letters, like this one. Frankly, Mabley’s letters and responses are usually boring. Mabley’s column in general is flat, or I would include him more often. There’s nothing awful about Mabley’s work—it’s just kind of meh.

But not today. This letter will shock you.

“My daughter, 4 years old, was admitted to a Chicago hospital with asthmatic bronchitis. I asked if I could stay the night with her. I was told that under no circumstances are parents allowed to stay at all. [After calling several hospitals, I found most had the same policy.]

“When we tried to leave, the poor child had such a look of terror in her eyes. I don’t think I shall forget that look till the day I die.

“You see, my daughter died the next day before I could get there.

“The hospital called me at 9:10 a.m. while I was getting ready to go there for 10:30 visiting hours. By the time I got there, she was dead.

“I may or may not have been able to do anything had I been there, but she would have been comforted.

“I know there are hospitals that are experimenting with having mothers stay with their children, because they find the child’s stay is cut by one to three days. It takes a strain off the nurses.

“I wonder if you could write an article on this subject.

—Susan Lawrence, Chicago”

“COMMENT: I could but it would not match the impact of your appeal.

“Hospitals rationalize their rules as the greatest good for the greatest number of people. But you separate the bad administrators from the good by their ability to relax a rule, to meet a human problem with compassion rather than a set of printed regulations. I hope some hospital administrators and trustees will benefit from this tragic experience.”

As I point out occasionally, 1972 is so much better when you can leave anytime you want.

July 24, 1972

Chicago Today

by Jeff Lyon

The Singer-Jackson alternate slate of delegates to the 1972 Democratic National Convention is heavily in debt from their trip to Miami. Let’s remember, the Singer-Jackson delegates got Mayor Daley and his elected delegates kicked out of the convention and replaced them.

About 1,200 people showed up to a fundraising auction to help pay off the debt—we never hear how big it is, but the $7,500 collected doesn’t come close to covering it—even though that’s $50,625 in 2022 money. Attendees paid a minimum $2.50 donation at the door (about $17 in 2022) and $1.25 for a drink ($8.50).

Oddly, Jeff Lyon initially describes the venue as an unnamed art gallery, then as a “club, partly owned by attorney F. Lee Bailey.” But the address is 632 N. Dearborn, so whatever it is, the important point is it’s inside the gorgeous red stone Romanesque building designed by Henry Ives Cobb in 1896 for the Chicago Historical Society, which left in the 1930s for its current home. Chicagology has a terrific page on the building.

Everybody loves this building, right? This deserves a leap down the Chicago History Rabbit Hole to look at all the businesses that have occupied the building since the Historical Society left. I don’t have time for that this week, but it’s on a list for future addendum posts. Meanwhile, legendary Chicago politico

Don Rose notes:

“The best use of the old historical society building was when it was the independent "Bauhaus in Chicago" Institute of Design--before the IIT bought ID and ultimately moved it to its campus.”

Back to the Singer-Jackson auction:

“In years to come, there’s got to be a lotta them sorry,” Lyon writes in his lede, meaning the many people who attended and passed up the auctioned items.

“Right at the ground floor last night they could have picked up some memorabilia of the 1972 Democratic National Convention that surely will be valuable some day.

“Like a match set of bath towel, face towel, and washcloth personally stolen by a Chicago alderwoman from a Hollywood, Fla., luxury hotel.

…. “And an alternate Illinois delegate’s badge.”

Lyon focuses on two highlights:

“One was the noticeable absence of the Rev. Jesse Jackson….There have been rumors that all is not well between Jackson and Singer. Since Singer showed up, as well as Ald. Anna Langford (16th), State Rep. Robert Mann (D., Chicago), black leader Albert Raby, Ald. William Cousins (8th), and Singer’s parents, among many others, Jackson’s absence was conspicuous.”

Second was Ald. Langford’s unexpected skill as an auctioneer. “[N]o one knows where she learned the rhythmic chant of the auctioneer. But sell she did.

“First came the towels from the Diplomat, where the Illinois delegation stayed. ‘I normally never steal towels from hotels, but I did this time for the auction. You can say you got towels stolen by an alderwoman. Anyway, I also took an ashtray and two coat hangers,’ she said.”

Ald. Langford got $50 for the towel set ($337.50/2022), $16 for two more towels ($108/2022), and $350 for the 10-foot Illinois banner used on the convention floor, bought by Rose Ratner of 4250 Marine Drive ($2,362.50/2022). Ratner said she would donate the banner to the Independent Precinct Organization (IPO).

Chicago Sun-Times

by James Campbell

Campbell leads with Ald. Langford playing auctioneer:

“All right now, here’s those towels. The bath towel, face towel and washcloth, stolen personally by me from the Diplomat Hotel. What do I hear? Twenty-five dollars, do I hear $25?.…Two dollars! Why baby, that won’t even make my bail.”

Campbell fills in some missing information as well: The Singer-Jackson delegates owe $30,000 for their Miami expenses—that’s $202,500 in 2022 money. So the $7,500 they raised at this event ($50,000 in 2022) is modest indeed. The total cost “of beating City Hall,” though, was originally $49,300 ($332,775 in 2022), so they’re working it down.

Also, Campbell tells that in 1972, the gorgeous former Chicago Historical Society building is the brand-new Gallery Club.

July 24, 1972

By Arthur J. Snider

Daily News Science Editor

“The nonsurgical treatment that relieved White Sox infielder Bill Melton’s agonizing back pains is not yet available to the public.

“The procedure, an injection of an enzyme into the back, is still under Food and Drug Administration surveillance….Fewer than a thousand patients have been treated throughout the country by a handful of surgeons since the first treatment by Dr. Lyman Smith of Elgin was disclosed by The Daily News on Jan. 10, 1964.”

This injection is only given to patients with a ruptured disk, and according to the News, about 9 out of 10 people get relief—which is the same as those who have surgery, but of course without having to undergo surgery.

July 25, 1972

Chicago Today

by James Pearre

Chicago Today is less optimistic.

“The experimental drug which relieved the pain of a slipped disc in White Sox Third baseman Bill Melton’s spine is not a ‘cure.’

…. “It remains to be seen whether the pain which has sidelined Melton since June 23 will return, but the rigors of professional baseball will not necessarily increase the chance of a relapse,” according to a specialist.

“Excessive strain or a sudden shock can dislocate a disc, forcing it to protrude from between the adjoining vertebrae.” This injection of an enzyme called “chymopapain” digests “dying disc tissue, which dissolves and is removed by the body waste disposal system.”

Another July 24/25 pairing:

July 24, 1972: Hanramania

Chicago Daily News

by Edmund J. Rooney

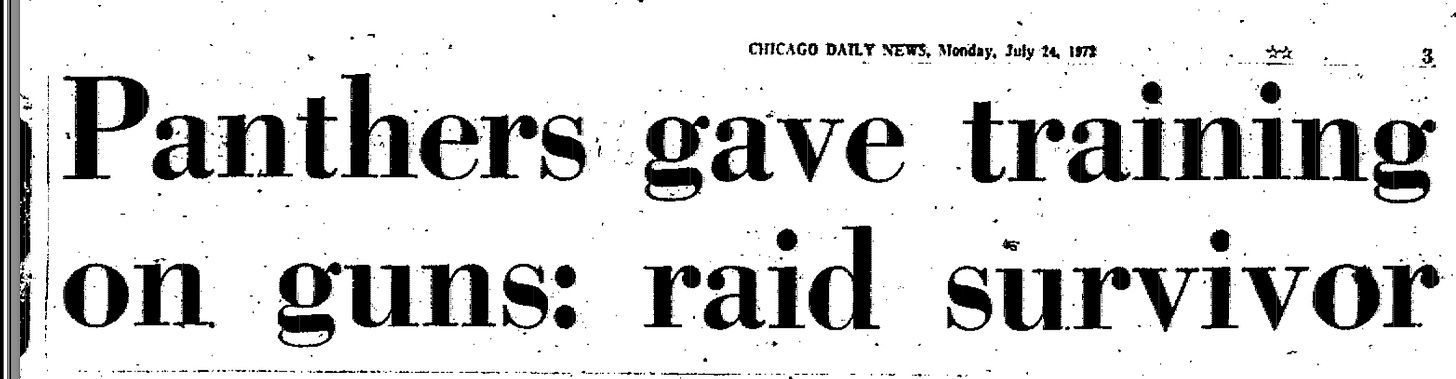

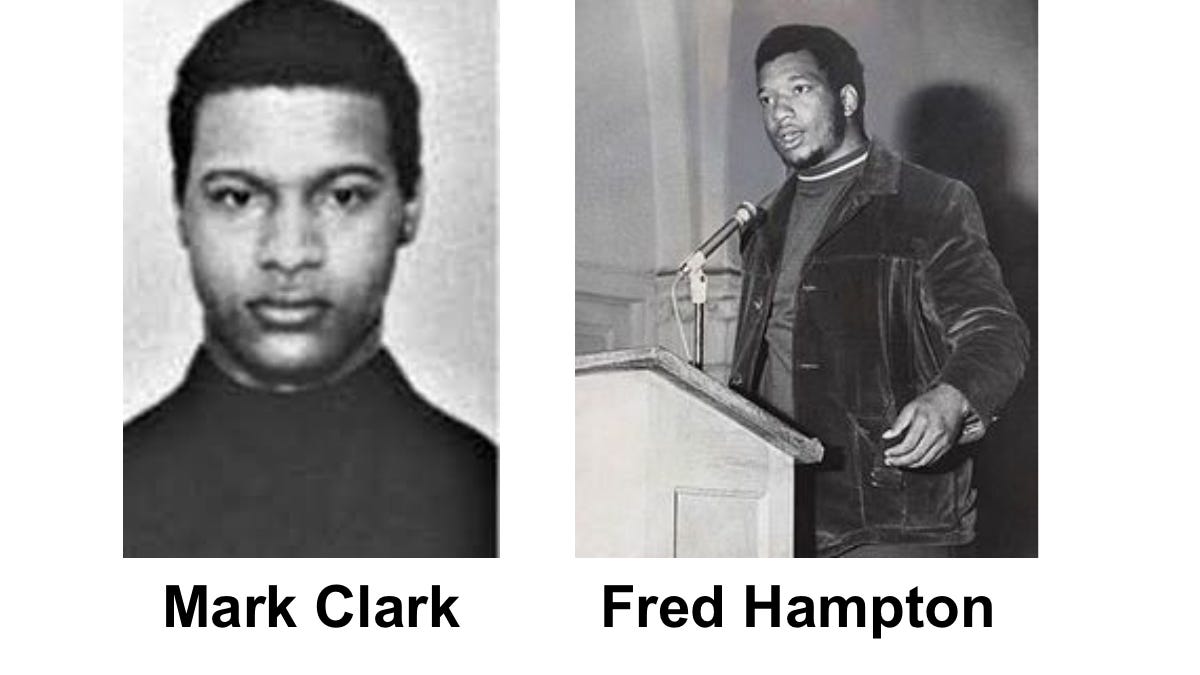

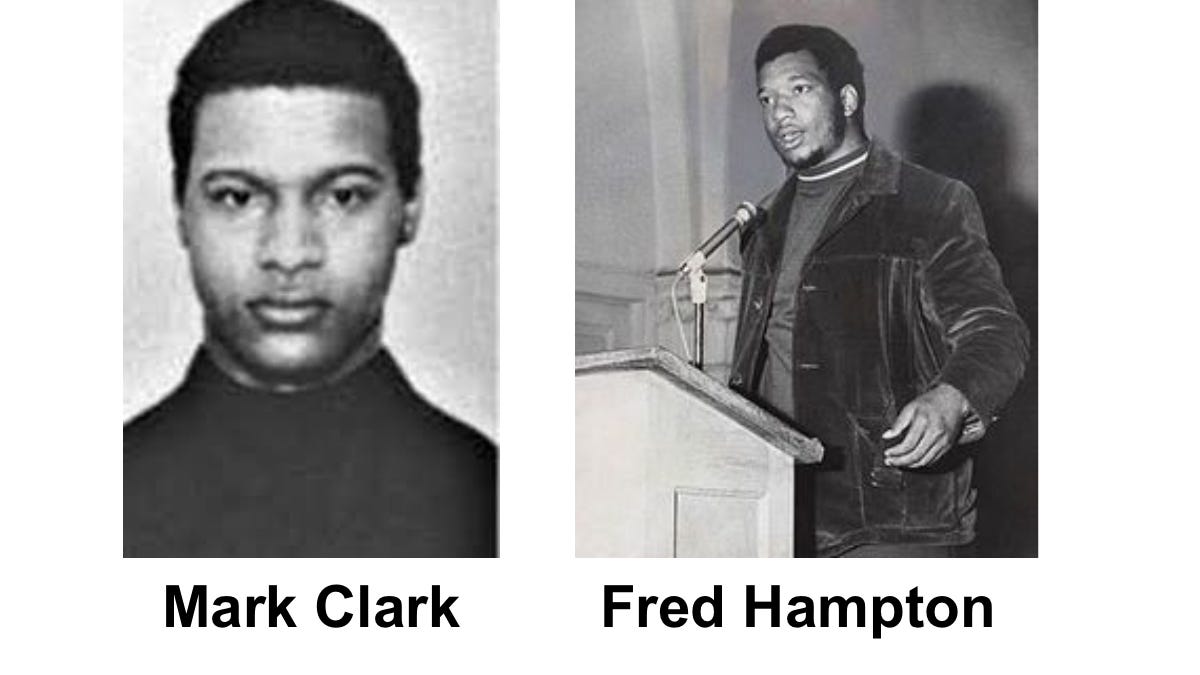

Deborah Johnson, the first survivor to testify from the 1969 pre-dawn state’s attorney police raid on a West Side Black Panther apartment that killed Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, gave “a vivid account” of the rain of bullets last Friday. First, Judge Philip Romiti agreed to her demand that the police defendants give up their side arms during her appearance. Johnson testified that she “felt the mattress vibrate pretty bad” during the shooting.

Recall that Cook County State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan and 13 co-defendants are on trial for allegedly conspiring to obstruct the investigation into the raid.

Johnson continued her testimony Monday, with the main takeaway here that the Panthers gave her weapons training when she joined them—though she already knew how to use a shotgun.

“Miss Johnson, who remained poised on the witness stand, specifically identified the shotgun found in the Panther flat as her personal weapon.

“She said it had been loaded and placed in the south bedroom, where she and Hampton were sleeping when the raid occurred, but had not been fired.”

Attorney Thomas Sullivan, who represents eight of the indicted policemen in the raid, “continued to seek testimony to support the defense contention that the Black Panthers were heavily armed, bore a hatred of the ‘Establishment,’ and were a threat to the police.

“Special prosecutor Barnabas F. Sears and assistant prosecutor Howard T. Savage vociferously objected, claiming that the politics of the Panthers have no bearing on the charges against Hanrahan and the others.

“Judge Romiti overruled the objections.”

July 25, 1972: Hanramania

Chicago Today

by Michael Garrett

It’s Tuesday, but Chicago Today gives us more detail from Monday’s continuing testimony by Deborah Johnson. The Daily News and Today are both afternoon papers, but Chicago Today’s deadline is clearly earlier than the Daily News. The Daily News consistently gives same-day accounts of the trial, while Today doesn’t. But Today’s details wonderfully flesh out the News’ version.

First, defense attorney Thomas Sullivan had Johnson identify various weapons found in the apartment, including “a gadget attached to the tip of the barrel of a .12 gauge shotgun. She called it a ‘choker,’ and added, ‘That’s for adjusting the spread of the shot.’”

Special prosecutor Barnabas Sears objected when Sullivan “asked Miss Johnson to examine a coloring book used by the Panthers in their teachings against society.

“‘Isn’t it the teaching of the Black Panther Party that political power comes from the end of guns, and isn’t it the principle of the party that every Panther member should have a functional weapon and 1,000 rounds of ammunition?’ Sullivan asked.

“‘No,’ Miss Johnson responded, after Criminal Court Judge Philip Romiti denied Sears’ objection.

“When one of the prosecution’s objections was upheld, Sullivan argued:

“‘This is not a case where the police broke in on the Holy Rosary Society. We have a right to show the kind of people we’re dealing with.’”

Now to Tuesday’s huge trial news:

By Edmund J. Rooney

“Special prosecutor Barnabas F. Sears, in a sudden and surprise move, told Circuit Court Judge Philip Romiti Tuesday he had come across ‘additional information and disclosures’ in the Black Panther raid case.”

Sears said he’d found “additional information and disclosures”, including statements by four of the seven surviving occupants of the Black Panther apartment, made to their own lawyers in December 1969, the same month as the raid.

After reviewing the transcripts, “Defense attorney Thomas P. Sullivan charged” that four apartment survivors “committed perjury”. “‘This new material raises a question whether this case should be prosecuted any further,’ said Sullivan.”

Sullivan told the courtroom that the transcripts showed that apartment occupants fired more than one shot. An FBI investigation previously determined that the Panthers fired one shot, while the police had fired over 80 shots.

In one example, Sullivan said that survivor Louis Trulock “under oath before the special county grand jury, said, ‘I did not fire a shot.’ But in statements to his attorney, Sullivan said, Trulock said he fired two shots.’”

Sears said one of his associates found the statements among files from the Illinois Defenders Project at Northwestern, while researching the case the previous weekend.

One of the other defense attorneys “rose in court to ask why the material submitted by Sears…had only now become available, 2 1/2 years after the raid.”

“There was no answer.”

“After Romiti left the bench, Hanrahan approached Sears for the first time in the courtroom. The state’s attorney appeared angry. The discussion between Hanrahan and Sears ended when defense attorney Leonard Hartenfeld pushed Hanrahan back from the prosecutor.”

The trial is recessed until Thursday.

July 25, 1972

x

From the Daily News:

From the Tribune:

The Trib interviews people on Michigan Avenue, catching many by surprise with the news that mercurial Cubs manager Leo Durocher has been fired.

“Bob Schumacher, an off-duty policeman out for a stroll, was taken aback when a Tribune reporter gave him the news. ‘You expect me to believe that?’ he asked. ‘I never thought they would fire him. If they were going to fire him, they should have fired him two or three years ago. He doesn’t know how to run a ball club, when to put a guy in, when to take a guy out. I think it was 40 per cent his fault that the Cubs didn’t win the pennant.’

“Mrs. Versie Smith, of 5107 S. Kimbark Av., a downtown janitress, said that she thought Durocher had an arrogant attitude. ‘I never liked the way he would deal with his players,’ she said, and then added, ‘But of course I’m a Sox fan so I don’t really care.’”

Have you read Chapter 2 of “Roseland, Chicago: 1972”? Follow the book’s hero, Steve Bertolucci, as he heads to work from the IC station at Randolph and Michigan, to his office in the IBM Building. And see what happens there.

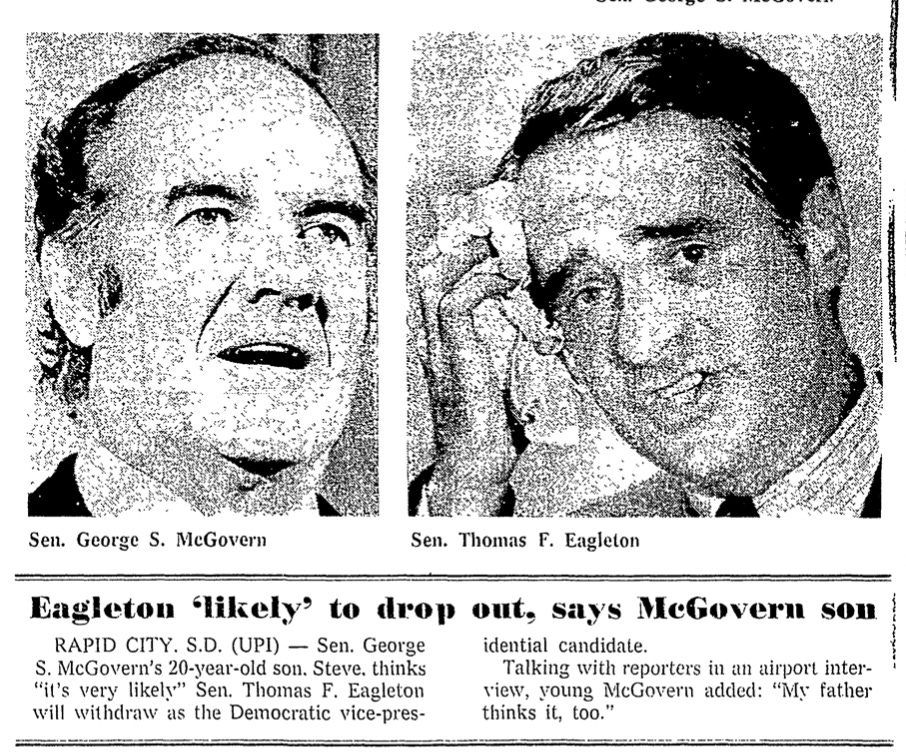

July 25, 1972: Eagleton

“CUSTER, N.D.—Sen. Thomas F. Eagleton of Missouri said Tuesday he has received psychiatric care and was hospitalized three times since 1960 for ‘nervous exhaustion.’

“The Democratic vice presidential nominee disclosed his medical record but denied vigorously that any of his illnesses were caused by alcoholism.”

“Eagleton said he entered hospitals voluntarily on three occasions ‘as a result of nervous exhaustion and fatigue.

“Eagleton said his hospitalization included electric shock treatments in 1960 and 1966.

“The 42-year-old senator said he made the disclosures following rumors about his health.”

July 25, 1972

Chicago Daily News

(AP)

“WASHINGTON—For 40 years the U.S. Public Health Service has conducted a study in which human guinea pigs, denied proper medical treatment, have died of syphilis and its side effects.”

Reading that in 2022, having always known about this abomination, it is still shocking to read the bare facts laid out so plainly by the Associated Press. And it’s hard to imagine how shocking it must have been as news in every sense of the word.

“The study was conducted to determine from autopsies what the disease does to the human body.

“PHS officials responsible for initiating the experiment have long since retired. Current PHS officials, who say they have serious doubts about the morality of the study, also say it’s too late to treat syphilis in any of the study’s surviving participants.”

The Tuskegee Study began in 1932 “with about 600 black men, mostly poor and uneducated, from Tuskegee, Ala., an area that had the highest syphilis rate in the nation at the time.”

Peter Buxtun, a 27-year-old U.S. Public Health Service worker, blew the whistle on the infamous Tuskegee Study by leaking the story to the Associated Press. He isn’t mentioned in this, the very first account anyone ever read about this 40-year atrocity. A few others had objected and tried to stop the study over the years, unsuccessfully. When Buxton couldn’t stop it either, he went to the press.

Today’s article uses an interview with Dr. J.D. Millar, chief of the venereal disease branch of the “PHS Center for Disease Control in Atlanta,” now known as the Centers for Disease Control. Dr. Millar headed “what remains of the Tuskegee Study.” Readers don’t know precisely how the AP approached the Center, or why they decided to be relatively forthright about the study once they were called on it—an unusual strategy these days. You may be surprised by Dr. Millar’s candor, even though he still seems somewhat clueless about the magnitude of this sin.

The Tuskegee Study’s victims signed up as participants ten years before penicillin was discovered to be a cure for syphilis, and it would be 15 years before penicillin became widely available, writes the AP. As Dr. Millar explains in his interview, 1930s, syphilis patients “were treated with mercury and arsenic….and the treatment was worse than the disease.”

However, Dr. Millar still admits there was “a definite moral problem” when the study began, and “a more serious moral problem was overlooked in the post-war years when penicillin became available but was not given to these men, and a moral problem still exists.”

“Looking at it now,” said Dr. Millar, “one cannot see any reason they could not have been treated at that time.”

The study included one-third patients who didn’t have syphilis, and two-thirds who did. Half of the patients with syphilis were given the pre-penicillin treatments, and the rest—about 200 people—weren’t treated at all.

“As incentives to enter the program, the men were promised free transportation to and from hospitals, free hot lunches, free medicine for any disease other than syphilis and free burial after autopsies had been performed.”

July 25, 1972

Chicago Today

If you’re a regular THIS CRAZY DAY reader, you’ll probably want to follow Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today too.

July 26, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times

It’s a bumper crop in Kup’s column today:

….

….

….

July 26, 1972

Chicago Daily News

By Robert Signer

“Patrolman Gary Konzak opened the door of the small refrigerator, tucked way in a corner of the suburban home’s laundry room, and there she was— ‘just the most gorgeous little girl I’ve ever seen.’

“And 5- year-old Virginia Kopp was still alive, although she had been imprisoned in the refrigerator for four hours while parents, neighbors and policemen searched frantically for her.

“She was like a tray of ice cubes when I took her out,’ said Konzak, 24. ‘Her arms and legs were rigid and in an unnatural position. I was sure she was gone.’”

Mrs. Virginia Kopp realized little Ginger was missing about 1:30 when she didn’t see her daughter playing in their LaGrange backyard. She called her husband, who came home. They soon called police, worried about an abduction.

But Officer Konzak decided from talking to neighbors that an abduction wasn’t likely, because they all told him Ginger was bright, and knew the boundaries where she was allowed to go.

So they conducted a search of the house, and Konzak noticed the refrigerator in the basement.

Konzak gave Ginger mouth-to-mouth resuscitation while an ambulance was called.

The article notes that she likely survived because “the refrigerator’s seal was old and worn and let the air in.”

For Younger Readers: Refrigerators used to close with a latch, so they couldn’t be opened from the inside.

From Wikipedia:

By the mid-1950s, deaths were not uncommon for children in the United States. For example, statistics for the 18 months from January 1954 to June 1956 show that 54 children were known to have been trapped in household refrigerators, and that 39 of them died. As the issue rose in prominence, people were asked not to abandon refrigerators and to detach the doors of unused refrigerators. At least one state, Oklahoma, enacted legislation making the abandonment of a refrigerator with a latch in a location where a child might find it illegal. At least as early as 1954, alternative methods of securing air-tight closures had been suggested, such as in patent 2767011, filed by Francis P. Buckley et al. in 1954 and issued in 1956. Starting in the mid-1950s, volunteers and health inspectors searched out abandoned refrigerators in order to detach doors and break latches. However, these efforts were not entirely effective and children still died inside refrigerators that had not been found and dismantled.

A 1956 federal law required manufacturers to figure out a way to change refrigerator door mechanisms to allow opening from the inside, which went into effect in 1958—and voila, the current magnetic door seal closure evolved.

So in 1972, little Ginger got stuck in her family’s basement refrigerator because it was old, and also lived because it was old.

July 26, 1972

Chicago Daily News

no byline

Do you remember State Sen. Bernie Neistein? We first met him here on December 9, 1971 when he got indicted for official misconduct and violating the Illinois Governmental Ethics Act. Neistein got swept up in the ongoing shady racetrack stock scandal that has also ensnared former Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner, still awaiting trial.

Neistein just got acquitted last week of failing to disclose his 1,557 shares of stock in the Fox Valley Trotting Assn. between 1967—when the state’s Ethics Ordinance went into effect—through 1971. He was the first official prosecuted under the ordinance, in fact. The judge dismissed the 1967-70 counts due to the statute of limitations.

For 1971, Neistein filed an amended statement a few months past that year’s deadline after he suddenly remembered the stock. The Springfield jury decided to let him slide on that, and Neistein went free. Bernie bought the stock for $4,600, and it’s now worth nearly $20,000.

Neistein bought the shady stock under his wife’s maiden name. The Daily News discovered it while digging into the wider scandal that blew up after Illinois Secretary of State Paul Powell dropped dead with about $750,000 in small bills stashed in his hotel room closet, a good portion of it in a shoebox. In settling Powell’s estate, his own large portion of shady racetrack stock came to light.

A federal grand jury spent a couple of years investigating. The alleged scandal is that Gov. Kerner and others helped the creation of new racetrack companies in exchange for a big chunk of cheap racetrack stock, liberally handed out to cohorts like Bernie Neistein. See Jan. 1-2 for an overview and update of that juicy story.

What with his indictment, Bernie decided/was told not to seek re-election to the state Senate seat from the West Side district he’s represented since 1959.

He also decided/was told not to run for his long-time position as the West Side’s 29th Ward Committeeman.

And yet, Bernie won the election for 29th ward committeeman anyway. How?

As Chicago Today’s Ray McCarthy reported then:

“No one ran for Democratic [29th] ward committeeman. Neistein had been told by his party chiefs not to run….But the cigar-chomping, violin-playing Bernie was not to be outdone. He garnered 1,200 write-in votes…although he will staunchly deny that he had anything to do with waging a campaign. Yet after the March 21 primary funny little cards were found which strongly urged voters to write in Neistein’s name.”

The problem with Bernie Neistein representing the West Side’s 29th Ward, even as ward committeeman, is that everybody knows he’s lived for years at the posh Carlyle, 1040 N. Lake Shore Drive, overlooking Oak Street Beach—

—and not at his 29th Ward voting address of 4123 W. Harrison, where Ray McCarthy noted “he hasn’t been seen in some time.”

Which brings us to today’s headline. Bernie won re-election to his committeeman post with 1,731 write-in votes, versus 56 votes for actual 29th Ward resident Thomas Durham. But three ward residents challenged the election based on Bernie’s residency. Bernie apparently was persuaded to throw in the towel, and has dropped out of the fight.

The end of a colorful chapter in Chicago politics! Read Ron Grossman's as-always fabulous profile of Bernie Neistein from April 13, 1999. Neistein’s Russian-Jewish father ran a tailor shop at Jackson and Pulaski, where young Neistein worked. The aspiring lawyer couldn't join top law firms since he was Jewish. So he went to work for the Machine instead.

Mayor Daley would ask Neistein to play his violin on election nights.

July 27, 1972: Hanramania, Daily News edition

By Edmund J. Rooney

After special prosecutor Barnabas Sears revealed Monday that his team had just found 2 1/2-year-old affidavits from survivors of the pre-dawn 1969 raid by State’s Attorney police that killed Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, Judge Philip Romiti recessed the trial until Thursday.

Now, the trial is further delayed because Romiti granted a request by lawyers for Cook County State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan and his 13 co-defendants for “an extraordinary hearing into circumstances” around finding that evidence.

“The new evidence, known as Defense Exhibit No. 29, consists of statements given to their attorneys by four survivors….The statements reportedly show that the survivors changed their stories about the raid in later testimony before the special county grand jury that indicted Hanrahan and 13 others.”

They’ll hear from 12 people “allegedly connected” with taking the statements. The first, attorney Francis (Skip) Andrew, testified Thursday. Andrew said he recorded statements from “three or four” Panther survivors in the upstairs bedroom of a house during “super secret” late night meetings. Andrew only remembered for sure talking to Deborah Johnson, and his only general recollection of the statements, he said, was that “no Panther had fired a weapon.”

Despite the dramatic above-the-masthead front page headline, the end of the article notes that Judge Romiti might end the trial, or he might not end the trial.

Chicago Today: Hanramania, Today edition

Michael Garrett

Chicago Today’s Michael Garrett adds some details that better explain today’s Panther trial proceedings:

Attorney Skip Andrew says the survivors’ recorded statements took place in December 1969, soon after the pre-dawn raid that killed Fred Hampton and Mark Clark.

Andrew agrees he was a personal friend of Fred Hampton’s, and was acting at the time as “chief counsel of the Black Panther Party”.

Andrew was present during the affidavit of Panther raid survivor Louis Truelock, and saw him sign it. Defense attorney John Coghlan asked why Andrew had Truelock sign the statement. Answer: “Louis Truelock seemed to contradict what I knew about the case. I wanted to protect myself.” Coghlan asked if Andrew knew at the time that “Truelock is reported to have tipped off police that guns were in the apartment.” Andrew did know about that.

“Truelock’s affidavit said he fired two shots from a pump-action rifle at police and heard Ronald Satchel, another survivor of the raid, fire ‘at least one shot.’ The Truelock statement is crucial to the defense because it differs radically from a prosecution contention that only one shot was fired by a Panther while more than 80 rounds were fired by police.”

NOTE: With no explanation, some papers spell this survivor’s name “Trulock” and some spell it “Truelock.”

July 28, 1972: Hanramania, Sun-Times edition

Chicago Sun-Times

by Kingsley Wood and Hugh Hough

Reminder, the Black Panther police raid trial is suspended while Judge Philip Romiti oversees a “voire dire” hearing on the authenticity of dramatic new evidence—affidavits allegedly made by survivors of the State’s Attorney police raid on the Black Panther apartment, given to their lawyer Francis Andrew in the weeks after the raid.

The affidavits were just discovered by a member of special prosecutor Barnabas Sears’ team, and they can’t explain why the affidavits have only just now come to light 2 1/2 years late.

The Sun-Times makes the most sense out of yesterday’s Panther courtroom proceedings, because reporters Wood and Hough note when something is new—like the question of a stool pigeon in the apartment—and why some points just don’t seem to make sense. In other words, they answer the nagging question, “Is it just me, or…” This is a good if small example of how readers may understand—or not understand—coverage depending on which newspaper they read.

The only time a stool pigeon came up before was in 1970, when Panther survivor Deborah Johnson “filed a court petition seeking to learn if any one of the other survivors was a police collaborator.”

“The state’s attorney’s office at that time did not disclose whether an occupant of the Panther apartment had tipped police to the presence of guns in the apartment or had later cooperated with police investigators.”

Now, it’s the defense—representing State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan and 12 co-defendant police officers—asking whether there was a stool pigeon in the apartment.

“The stool pigeon point came up as defense Atty. John P. Coghlan was questioning [former Panther attorney] Francis E. Andrew about a 11-page statement that Panther survivor Louis Truelock purportedly gave to Andrew when Andrew was his lawyer.”

Coghlan asked Andrew if Truelock was ever suspected of being a stool pigeon. “I heard people say that,” Andrew answered.

In his alleged statement to Andrews, Truelock said he fired two shots at the police raiders.

“The Truelock statement is considered crucial to State’s Atty. Edward Hanrahan and his 13 codefendants because it differs from the prosecution contention that police fired more than 80 shots while only one shot was fired by a Panther Party member.”

Nobody further explained anything about the alleged stool pigeon issue during court yesterday, but the Sun-Times covers exactly what any confused reader must be wondering by attributing the thoughts to “courtroom observers”:

“Courtroom observers pointed out that if Truelock were established as a police informant, that might bring into question the credibility of his [newly discovered] account which supported the police version of additional gun-firing by Panther apartment occupants.”

Under questioning by Coghlan, Andrew admits he was Truelock’s lawyer, representing him in court four or five times in early 1970; that Truelock made a statement to him and signed it in front of two other witnesses on Jan. 28, 1970; and that the newly-discovered statement is “in the same form” as the 1970 Truelock statement.

But Andrew won’t confirm that the newly-discovered signed Truelock statement is in fact that same statement. Andrew claims he doesn’t remember ever reading the statement.

Coghlan: “Do I understand that you had the Truelock statement in your file and didn’t read it when you went to court four or five times?”

Andrew: “I don’t remember reading the instrument. I would think I would have read this statement because that’s what an attorney ought to do. But I don’t remember if I did.”

Tucked into the article is this little promo:

July 28, 1972: Hanramania, Fitz edition

Regular TCD readers will know that Tom Fitzpatrick is the Sun-Times’ main columnist, their Mike Royko equivalent. Fitz has been following the Panther case all along, and his sympathies clearly do not lay with State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan and his 13 codefendants.

Fitz seems confused and conflicted as anybody by the current twist in the Panther trial, and this is how he handles it: Listing everything he basically knows and thinks about Francis Andrew, and leaving the question wide open about what Andrew knows, and why he isn’t talking.

“Your name is Francis (Skip) Andrew and you are an attorney who represented members of the Black Panther Party in Illinois.

“You were one of the first to hear about the deaths of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark on Dec. 4, 1969 in the apartment on West Monroe.

“It was you who got Norris McNamara to call Mike Gray and have the film footage taken that ultimately became the dramatic highlight of ‘The Murder of Fred Hampton.’

“And you are the one who went through the Hampton apartment with the skill of a surgeon, uncovering evidence that even the police department’s crime laboratory technicians missed.

“You have been a lawyer only since 1968. You specialize in defending unpopular causes. You have a courage. It didn’t even bother you when Judge Joseph A. Power, the chief of the criminal courts, slapped you in jail for contempt when you refused to turn over the door of the Hampton apartment which you removed as evidence.

“But now you are in a spot.”

These newly-discovered survivor statements, allegedly the same ones made to Andrew soon after the 1969 police raid, “are dynamite,” Fitz notes, “because they contradict testimony later given by the same people to the grand jury.”

Fitz further notes that Andrew had the right of attorney-client privilege back then to withhold the statements, but that’s all moot now. And Fitz writes that Andrew must have noticed Ed Hanrahan’s reaction during Andrew’s testimony.

“Hanrahan hasn’t smiled so much since the night he won the Democratic primary over Raymond K. Berg. They think they’ve got the case locked now.”

Truelock’s statement—in which he says he shot twice at the police, and fellow Panther Doc Satchell shot once— “puts a whole new light on the case, if the statement is true.”

Fitz is impressed by how Andrew holds up under questioning by defense attorney John Coghlan, and he notes that Andrew will continue that questioning the next day at 9 a.m.

“John Coghlan is a lawyer but he moves and talks like a police captain. He’s tough and he’s mean. To sit there on the witness stand all day long and tell him you don’t remember anything is going to be the hardest thing you’ve ever done in your life.”

Fitz gives us a longer bit of Thursday’ testimony that makes Andrew sound, well, ridiculous. Here’s the tail end of the excerpt, after Andrew denies anything but a vague recollection of taking the statements and claims he just remembers “listening to music” that day with the Panthers:

Coghlan: Do you know Fred Hampton was killed in the raid?”

Andrew: “I was told that he was.”

Coghlan: “Do you know how many survived?”

Andrew: “No sir, I don’t.”

Coghlan: “You were their attorney, weren’t you?”

July 28, 1972: Joseph O’Shea

Chicago Tribune

by Fredric Soll and Patricia Leeds

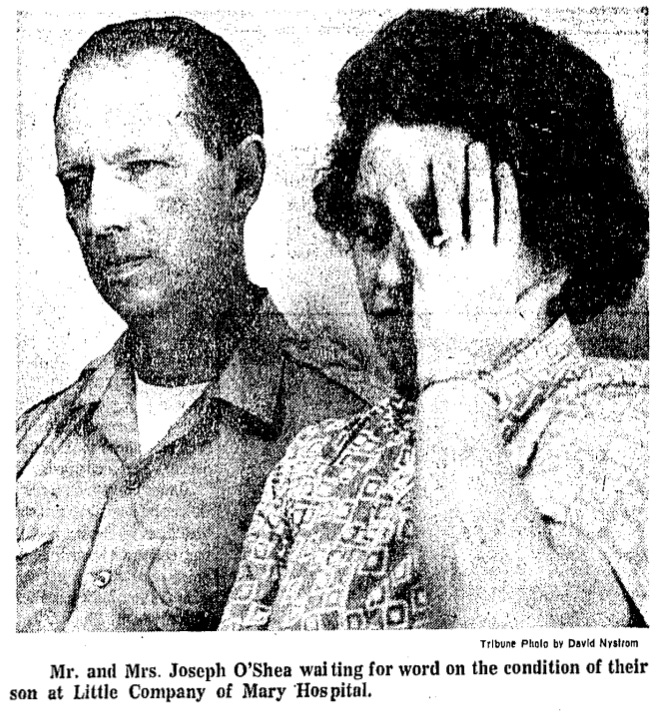

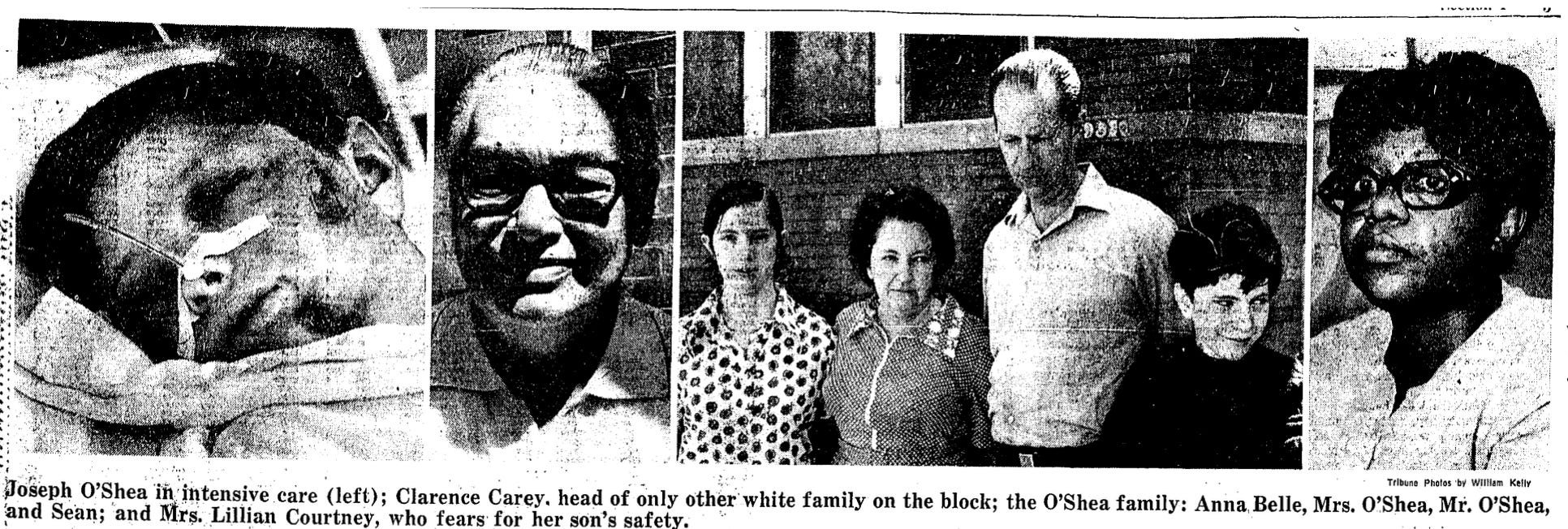

“At 10:45 p.m. Wednesday, Mrs. Joseph O’Shea walked into her home at 9311 S. Throop St. and found her 11-year-son, Joseph, lying in a pool blood.

“‘Mommy, I’ve had a nightmare,’ said Joseph.

“The boy, a hemophiliac, had been watching the Johnny Carson show, he said, when two black youths broke into the home, beat him up, ripped the phone out of the wall, set a small fire at the back of the house, and walked out with several of the family’s possessions.

“The O’Sheas are the only white family on an all-black block in a changing neighborhood.” [Note: In fact, they are one of two white families left on the block.]

Mrs. O’Shea drove Joseph to Little Company of Mary Hospital in Evergreen Park, where her husband works as a security guard. “‘On the way to the hospital, I was holding him,’ she said, ‘and he looked up at me and asked, ‘Mommy, am I going to live?’

“Mrs. O’Shea said that was a normal question for a hemophiliac to ask. The disease makes blood flow difficult to stop.”

Chicago’s daily papers cover the story of Joseph O’Shea starting Friday morning, though the home invasion happened Wednesday. We never hear why the afternoon papers failed to pick up on the story for Thursday’s editions.

Per Chicago Today, Joseph had just emerged from a coma but remained in serious condition.

“The attackers also set fire to a rug in the family’s home and opened gas jets on the kitchen stove,” according to Today. “The house was ransacked but only a saxophone and $10 appeared to be missing, police said.”

The O’Shea home at 9311 S. Throop is in Brainerd, just north of Roseland.

The Sun-Times says Joseph needed two pints of blood so far for his injuries, including an operation for his fractured jaw. He’ll be variously identified as being either 11 or 12 years old as coverage goes on.

The Daily News adds that Joseph’s injuries include severe bruising and a broken cheekbone.

The Tribune sat with Mr. and Mrs. O’Shea in the Little Company of Mary Hospital waiting room as Joseph underwent surgery.

“Mrs. O’Shea said the family of five had had no problems in the neighborhood since it changed to practically all black about three years ago.

“‘Oh, we weren’t friends with the neighbors, but we’d say hello when we saw each other. We didn’t move when everyone else did because we liked our home—we have lived here 20 years. I always felt we could get along with everybody.’”

“‘We always felt that if we left everyone alone, everyone would leave us alone,’ said the father, Joseph.”

Neighbor Darnell Johnson, 13, told the Tribune he played baseball with Joseph “all the time.”

“‘Yeah, he’s a nice kid,’ said Johnson. ‘I don’t know why anyone would want to hurt him.’”

Darnell was surprised to learn that Joseph—and is older brother—are both hemophiliacs. Mrs. O’Shea explains they didn’t tell anyone, because they didn’t want to be treated differently.

Mr. O’Shea was on duty at the emergency room when his own car pulled up to the door, his older son Sean jumped out and said, “It’s Joseph.”

“Police are speculating that an area gang called the Junior Rangers might have been behind the beating,” the Trib reported. “Joseph was found with the letters ‘J’ and ‘R’ on his forehead.”

“‘I guess I’ll just never understand why anyone would do a thing like this,’ said a tearful Mrs. O’Shea. ‘But I’ll tell you this, we’re going to move out of here as soon as we can.’”

July 28, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Eagleton

Chicago Today

Sen. Thomas Eagleton doesn’t make Chicago Today’s front page, but they run two terrific stories on the giant national issue of whether Eagleton should remain on the Democratic ticket as Sen. George McGovern’s running mate, now that he’s disclosed that he was hospitalized three times with “nervous exhaustion and fatigue” with treatment including electric shock treatments as recently as 1966.

by David W. Merrick - Knight Newspaper Service

“WASHINGTON—A still unknown phone caller who claimed he wanted to help tried two weeks ago to tell George McGovern’s campaign strategists about the psychiatric history of his running mate but was dismissed as a crackpot.”

Later in the story, we read that this single caller contacted both John S. Knight III, grandson of the Knight Newspapers chairman and editorial writer at the Detroit Free Press, and also top aides Frank Mankiewicz and Gary Hart at the McGovern campaign. That means the Knight Newspapers investigated the story for two weeks without publishing a bombshell exclusive.

Mankiewitz says he waved it off: “We get a lot of crank calls.”

“Instead, it was not until a team of reporters from Knight Newspapers sought an explanation of Thomas Eagleton’s hospitalization and therapy that the McGovern forces learned of Eagleton’s medical background.

“Eagleton had anguished over whether to tell McGovern of his past problems. McGovern had asked him in Miami Beach whether Eagleton had ‘any problem in the past’ that he thought was significant.

“Eagleton said no.”

Within hours of Eagleton’s nomination, Merrick reports today, Knight Washington reporter Clark Hoyt was assigned to profile him. Hoyt and others “were aware of rumors of mental depression and possible alcoholism involving Eagleton but had no reason to believe the rumors were true.”

But by the time Hoyt got to St. Louis to start through clipping files at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch—For Younger Readers, this is how research got done before digitized databases and Google—his ultimate boss’s grandson had called him about the phone call tip.

Are you wondering how the Knight people took a vague phone tip and turned it into a national story that forced the Democratic vice presidential nominee to drop out? People with reporting background particularly can intuit what happened next, but it’s interesting to read their account. It’s kind of like a preview to “All the President’s Men.”

Knight III “persuaded” the phone caller to try to get more solid information and call back. The caller came back with the “name of a St. Louis psychiatric hospital and an approximate date and the name and address of a person alleged to have been on the treatment team.”

“Hoyt went to the St. Louis address and got what could be considered only indirect confirmation—a refusal to discuss the matter couched in terms that strongly implied it was true.

“Hoyt then began contacting St. Louis-area political associates of Eagleton from earlier years, maintaining an indirect approach about the medical situation. At least two of the contacts—one an officer of the Committee to Reelect the President, the other a Democrat—volunteered facts about Eagleton’s hospitalizations, but neither mentioned electroshock therapy.

“Those hospital names and dates did not coincide with the caller’s information or with two brief stories in the Post-Dispatch files referring to Eagleton hospitalizations for ‘gastro-intestinal’ problems and, later, for ‘sudden weight loss.’”

At that point, the reporters knew the story was true—they just had to figure out which parts.

Knight Newspapers took their information to Frank Mankiewitz, asking for medical files, “an interview with [Eagleton’s] doctor or psychiatrists” and “an interview with Eagleton”. The Knight people thought they had a deal with McGovern’s people to receive all that, and to publish their exclusive, before McGovern and Eagleton announced the news and held a press conference. All in exchange for holding publication until McGovern could talk to Eagleton.

But Mankiewitz later came back to say none of that would happen, because Eagleton was going to hold an immediate conference before any news story could appear.

“About an hour later, Eagleton had his press conference and the Eagleton-McGovern version of the story was out, on their terms.”

This story keeps mentioning all the McGovern people and Democratic officials who thanked them for handling the story “responsibly.” Knight Newspapers was clearly worried about public blowback, even after Eagleton broke the story himself.

During a later interview, Eagleton said he offered to resign but McGovern declined the offer.

“Eagleton said in the interview that he and his wife, Barbara, had discussed en route to the convention the possibility that if Eagleton got nominated the therapy question would arise. They decided to say nothing and see what happened.”

by Mart Gerchen

“ST. LOUIS—Sen. Thomas Eagleton’s hyperactive public conduct could easily be mistaken for drunkeness by those who either don’t know him or dislike him, two of his associates contend,” reports Mart Gerchen.

“‘He has enormous reserves of energy,’ said Stephen Darst, who was an alderman here in 1968 when he worked on Eagleton’s successful Senate campaign.

“‘He was exuberant at all hours. Maybe people attributed it to alcohol, but I never saw him stumble or heard him slur his words,’ Darst said.”

A reporter from Missouri’s capital, Jefferson City, agreed that Eagleton is “a manic sort…He’s a noisy guy who talks a lot and fast.” The reporter says Eagleton is witty.

“When Eagleton campaigns, he is outdoors often and his nose quickly turns red from the sun,” the reporter continued. “Also, he likes to take off his coat when he talks, and doesn’t smooth his hair when the wind musses it up.”

“As he talks, trading quips loudly and rapidly, waving his hands and drawing attention to himself, he looks like a barroom habitué, in [the reporter’s] opinion.

“‘A friend of mine is a member of Alcoholics Anonymous and he says he has never seen any of the symptoms of heavy drinking in Eagleton,’ [the reporter] said.”

July 28, 1972

Chicago Today: WLS full page ad

July 28, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Hanramania

In the ongoing “voir dire” hearing into the newly discovered 2 1/2-year-old statements by survivors of the 1969 raid on a Black Panther apartment by State’s Attorney police that killed Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, we learn that so far the prosecution has only turned over the last page of witness Deborah Johnson’s old statement.

The defense wants the rest of it.

Johnson’s attorney, James Montgomery, has the rest of the statement but refuses to turn it over because he says Johnson hasn’t released him from attorney-client privilege. Montgomery says he never read the statement, so he can’t say what’s in it.

Judge Philip Romiti will rule on whether the attorney-client privilege is valid or not.

Meanwhile, there’s a new detail on the statement and testimony of Louis Trulock, who we’ve only recently read “tipped off” the police that Panthers had guns in the apartment.

The newly found statements include a 41-page signed affidavit from Trulock, dated Jan. 28, 1970. So Trulock’s statement was given separately from the others, who gave theirs in December 1969, soon after the raid. A portion of Trulock’s statement was read into the court record during questioning.

Trulock “told the [later] grand jury that he did not fire a weapon,” but in the statement, Trulock said “that he fired an automatic pump rifle two times ‘and it made everybody get out of the way.’”

July 29, 1972

July 29, 1972: Joseph O’Shea

Chicago Sun-Times

By Paul Molloy

The Sun-Times runs a feature on the O’Shea family today with pictures that did not reproduce well on microfilm, including Mrs. and Mrs. O’Shea sitting sadly on their front porch at 9311 S. Throop.

11-year-old Joseph remains in serious condition, “whimpering to his mother, ‘Just protect me’” as he recovers from a “a shattered jaw, a broken cheekbone and head lacerations.”

It turns out this was the fourth break-in at the O’Shea home since school let out, a few things stolen each time.

“And now this,” says Mrs. O’Shea. “I wonder what I’d do without my religion today. If you could see that little boy’s face—how brutally they attacked him. It’s unbelievable. He can’t even open his eyes. He thinks he’s going to die. Four or five times, at the hospital, he said, ‘Am I going to live?’”

“Police were seeking two teen-aged boys who, armed with knives, apparently struck young O’Shea with a telephone which they had ripped from the wall before ransacking the one-story, yellow-brick bungalow.”

As we read yesterday, police suspect a local gang called the Junior Rangers may be responsible, because the letters “J” and “R” were written in green ink on Joseph’s forehead. Now, Mrs. O’Shea tells the Sun-Times that “these boys threatened Joseph with knives and told him he had to join their gang. He told them: ‘I won’t join.’ But he’s afraid of them.’”

It’s unclear if that incident happened before, or during, the home invasion and attack. If earlier, it’s unclear whether Mrs. O’Shea knows that the boys who threatened Joseph are the same youths who invaded the house and beat him.

Mrs. O’Shea is a “computer operator” who works 6 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. Her husband is a security guard at Little Company of Mary Hospital working 3:15 p.m. to midnight, says Mrs. O’Shea, “so one of us is at home to care for the children.”

“I’ve been praying all the time since this happened,” she says. “I just pray that the people who hurt him won’t hurt anybody else.”

July 29, 1972: Joseph O’Shea and Kurt Marohn

Chicago Daily Defender

no byline

“Police are still seeking two black youths who broke into one of the last two white-owned homes in a changing Southside block, then robbed and severely beat the 12-year-old son of the owners. The assailants also attempted to burn the house down with their victim inside and unconscious on the floor.”

The Defender goes over all the known facts of the case, and adds:

“The attack was the second within two days apparently perpetrated by blacks in changing neighborhoods—a reversal of the pattern wherein dozens of black families have been firebombed and vandalized as they became the first minority families to move into white communities.

“On Tuesday, unknown vandals threw a Molotov cocktail which hit the front door of 7816 S. Emerald ave., owned by the last white family on the block.

“Kurt Marohn, 67, told police that everyone in his home was asleep when the sound of breaking glass awakened them. He discovered his front porch in flames, but soon extinguished the fire.”

July 29-30, 1972

July 29, 1972: Hanramania

Chicago Today

by Michael Garrett

As the voir dire hearing continues on the newly discovered 2 1/2-year-old statements by four survivors of the 1969 State’s Attorney raid on a Black Panther apartment that killed Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, Today’s Garrett sums it up this way:

“Purportedly, the survivors originally admitted [in the newly found statements] that at least five occupants of the West Side apartment had weapons and fired at least five shots at the state’s attorney’s raiders.”

On Friday, the court heard testimony from Thomas Nolan, a Catholic Charities social worker and friend of former Black Panther attorney Francis (Skip) Andrew who witnessed Louis Truelock’s affidavit signature. At first, Nolan told defense attorney John Coghlan that the newly surfaced affidavit looked different, but later said it “is substantially the same.”

“Q—Do you recall in the statement you read in 1970 that Truelock said a sergeant from the state’s attorney’s office and officer [James] Davis were in Hampton’s room the night of the raid and that Davis emptied his handgun at the chairman [Hampton]?

“A. - I don’t have any recollection of the dramatic phrase of his emptying his gun. I recall that Davis laid his gun on his arm, aimed it at the chairman’s head and body and fired.”

July 30, 1972

Chicago Today: Woman road construction worker

This is news in 1972.

July 30, 1972: Joseph O’Shea

Chicago Tribune

by Clarence Page

Young reporter Clarence Page, who would go on to become a Tribune and syndicated columnist, visits the block where 11 (or 12)-year-old white Joseph O’Shea was brutally beaten by two Black youths who broke into his home Wednesday night while the rest of the family was out, and Joseph was watching Johnny Carson on “The Tonight Show.”

The O’Sheas are one of the two last white families on the 9300 block of South Throop, which underwent racial change about three years earlier. It’s just north of Roseland.

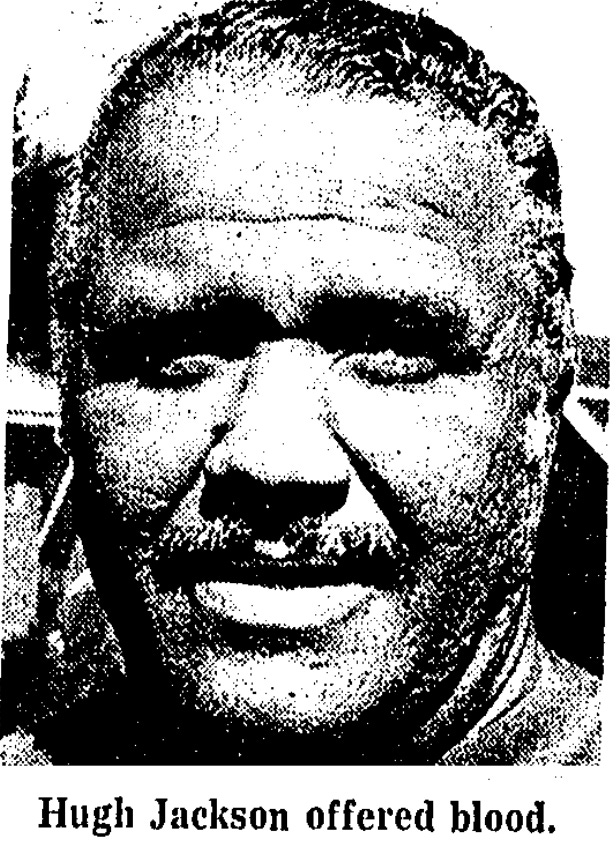

“Black neighbors of the O’Shea family…have reacted with sympathy and offers of blood donations to the beating of Joseph J. O’Shea, 11, Wednesday night by persons who invaded his home,” writes Page.

“Black neighbors expressed shock and embarrassment yesterday over the incident, which police believe was committed by two black youths. Thru phone calls, letters, and personal visits, black families have offered help.

“‘I may be a proud black man, but no one can be too proud to help this unfortunate boy,’ Hugh Jackson, 45, of 8520 S. Wabash Av., said yesterday as he offered blood. ‘I would do this for anybody. I hope I can correct some of the damage.’”

“Mrs. Lillian Courtney, 9310 S. Throop St., who sent her son to the O’Sheas with a card expressing her sympathies, said: ‘I think it’s the worst thing that could happen. I thought of how it could have been my child, who’s only 7. We’ve lived here about 11 months and hadn’t talked with the O’Sheas too much. But we always waved to each other in the morning on our way to work.’”

“Willie Holmes, 9301 S. Throop, said his family was the first black household on the block in 1968 and ‘we didn’t have a bit of trouble. I hate to see this happen to the O’Sheas. They’ve always been good neighbors.’”

“The other white family on the block is that of Clarence Carey, 61, of 9357 S. Throop St., director of Jones Commercial High School and father of Bernard Carey, Republican candidate for Cook County State’s Attorney. Carey has not experienced any criminal acts since he moved into the neighborhood 37 years ago.

“‘I wouldn’t move unless I was forced to,’ he said. ‘It’s still a nice neighborhood. The new neighbors have maintained their homes beautifully.”

Meanwhile, the O’Sheas were cleaning their ransacked house, planning to move, and Mr. O’Shea said they wouldn’t leave the home “unguarded” again.

Chicago Sun-Times

The Sun-Times’ Paul Molloy reports on the investigation into the beating of Joseph O’Shea, who is “still critically ill” according to Little Company of Mary Hospital medical director Dr. Peter J. Talso.

Sgt. Alvin Palmer of Area 2 Robbery says up to 60 youths have been questioned, most connected with the Junior Rangers street gang. They’re checking some of their fingerprints with those left in the ransacked house at 9311 S. Throop.

Joseph O’Shea’s father “said he was convinced the boy knew his attackers and would be able to identify them. ‘But he’s in great fear,’ he said.

“The father said the Junior Rangers made their headquarters in a home several houses down the street, ‘but it’s been very quiet since (the Wednesday attack) and we haven’t seen any of them on the street.’

“The O’Sheas said their one-story home, which they bought for $20,000 in 1952, had been broken into on three previous occasions since the start of the school summer vacation last month.”

July 30, 1972

July 30, 1972

July 30, 1972

Chicago Today

by Mary Leonard

As the Eagleton affair winds on, the papers have prepared think pieces for the Sunday papers.

“For in the few days time since Eagleton revealed that he was hospitalized in 1960, 1964, and 1966 for depression and nervous exhaustion, the barometer of public sentiment has been unsteady, to say the least,” writes Today’s Mary Leonard. “Allegations that alcoholism may figure in the picture have done nothing to quell the fears of an electorate anxious to assess the competency of the candidate.”

Some “high-ranking Democratic Party officials, financiers, and newspaper editorialists” have called on Eagleton to drop out, while others think it’s a marginal issue.

But, says Leonard, forget all that.

“Just how does the average middle American voter respond to health—particular a candidate’s mental health—as a legitimate campaign concern?

“It is an issue that, for all practical purposes, the voters in the United States have never faced before.”

But Leonard undermines her own thesis. While it’s true that the American public never fully understood the physical health issues of people like Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt or John F. Kennedy, she brings up the then-recent candidate issues which show the beginning of modern disclosures/leaks/accusations on candidate health which preceded the Eagleton situation—and which focused on mental health.

Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, running against LBJ in 1964, “was accused by author-publisher Ralph Ginzburg of suffering from paranoia and general mental instability. Goldwater sued for libel, was awarded $90,000, and won the case all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court.”

True, but Goldwater spectacularly lost the election, which is often blamed on the successful strategy to portray him as a right-wing loon who would blow up the whole world.

Younger Readers, if you ever hear the term “Daisy Girl,” this is what they mean:

Less well known now, but from Leonard’s phrasing, clearly well known in 1972: “Of course there were the allegations in 1968 that then-candidate Nixon had once sought psychiatric counseling. The charges were vigorously denied.”

George Washington, Leonard notes, “never had shock treatment—or if he did, no one ever knew about it.”

For Younger Readers: This is a joke. Electricity hadn’t been discovered yet.

It appears “in the minds of many Americans, the worlds of mental health and physical health are light-years apart. Perhaps the public has been overfed with Dr. Strangelove—

— and ‘The President’s Analyst.’”

Bingo! Any week that lets us refer to both “Dr. Strangelove” and “The President’s Analyst” is a very good one.

“In a nuclear age, we visualize panels of buttons in the executive suite, buttons that are the lofty responsibility of the commander-in-chief—or the responsibility of his successor, ‘only a heartbeat away’ from the Presidency.”

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.