To access all website contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 is part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. Follow THIS CRAZY DAY on Twitter, @RoselandChi1972.

August 21, 1972

Chicago Daily News, front page

by James Kloss

“An army of more than 10,000 tromped down Michigan Av. in Monday’s marathon American Legion convention parade.

“The mind-boggling and knee-buckling one-mile march down a Michigan Av. that was more muggy than magnificent was expected to take at last seven hours.”

I know it sounds crazy, but that’s what it says. Seven hours.

“At least 20 persons were treated for heat exhaustion at Balbo and Michigan, the end of the long parade route.”

Imagine them all in front of the then Conrad Hilton; imagine them mixing with the ghosts of the 1968 police rioters smashing protester heads during the Democratic National Convention, which happened in the same spot. Imagine them all around you the next time you walk past the Balbo/Michigan intersection.

And that was all despite the first aid stations scattered along the entire route “to assist old soldiers and sun-struck spectators who faded away during the heat.”

Naturally, Mayor Daley was the honorary parade marshal, riding in a white limousine.

“Just before the march began, Suzanne Davis, 11, of Harvey, broke through security to get the mayor’s autograph as a bodyguard stared at the sky and said, ‘I won’t see a thing.’”

Is that a Hogan’s Heroes allusion??

August 21, 1972

Remember Police Sgt. Stanley Robinson, who disappeared in late June after he and four to five other Black Chicago cops were accused of forming a police “hit squad” as part of a narcotics trafficking ring?

The Hit Squad, as it became known, allegedly murdered five to six West Side Black men, all killed gangland-style with a gun shot to the back of the head after being forced to wade into the South Branch of the Chicago River or the Sanitary Canal. See June 20, 21, 22, 25, and 26 for more background.

As the Trib’s David Young summed it up earlier this month, Robinson’s disappearance “was shrouded in mystery. An anonymous caller phoned the police early one morning to report a man had been abducted on the West Side by four other men. Police went to the scene and found the car Robinson had been using. A few days later, Police Supt. James B. Conlisk Jr. announced the abduction was a hoax: Robinson had been identified by a voiceprint as the anonymous caller.”

Stanley Robinson’s nickname was “The Fox,'“ Young reported. And the fox is back in town.

The Trib’s David Young owns this story now. The other papers actually barely even cover it—they don’t want to acknowledge the Tribune’s scoop, no doubt, and frankly, what should be a massive story is overshadowed very quickly by an even bigger local scandal. You’ll see.

“Police Sgt. Stanley B. Robinson, who disappeared while under investigation into an alleged police murder squad, met last night on the North Side with a Tribune reporter and promised to turn himself in to authorities later this week,” Young opens.

“Sporting a beard, Robinson met with the reporter on a darkened pathway after making certain he was not followed and said, ‘I’m returning to clear myself of these ridiculous charges.’”

That dramatic meeting took place after a week of negotiations between Robinson’s friends and the Tribune. Young, who continues the silly style of referring to himself in the third person throughout the story, was told to meet Robinson in a North Side bar. As he waited, Young was called to the phone. A male voice asked if Young had been followed. Young said no, and received a new meeting address—the darkened path.

“I just want everybody to know in advance that I am going to [surrender],” Robinson told Young, explaining later that the elaborate precautions for their meeting were to ensure he wouldn’t be executed first.

“If all these wild stories about hit squads are true, how come nobody has been charged with anything or indicted yet?” Robinson asks Young.

Hmm, good question. The most mysterious part of the whole police Hit Squad scandal is what the FBI or the police have on Robinson and the other suspects.

Second most mysterious point: Why would David Young bring a pipe and smoke it while interviewing anybody for any story, much less this one?

The “wild stories” about the alleged Hit Squad included charges that it operated by pulling victims over for a traffic stop, then making them ride in the squad car to their deaths.

“The policemen, according to some accounts, acted as uniformed executioners during a falling out among members of the police-criminal narcotics ring,” writes Young.

“The FBI investigation reputedly centered around information furnished by three persons, one of whom was supposed to be an intended victim and a second who was to have killed him,” Young reminds readers.

Robinson will turn himself in tomorrow, accompanied by a lawyer, Young, and a photographer. But it’s anticlimactic—especially compared with the secret meeting in this article. For now, Robinson is charged with official misconduct and disorderly conduct for faking his own kidnapping.

August 21, 1972

August 21 and 22, 1972

All the papers cover the horrifying story of Mrs. Helen Lyons, 72, shot to death by a 13-year-old outside her South Shore apartment building at 7601 S. South Shore Drive. She’d been sitting with her neighbor on folding chairs, enjoying the summer evening.

The details slightly change between accounts, specifically regarding how many kids were involved and exactly how the conversation went before Mrs. Lyons’ murder. Otherwise, basic facts and statements are consistent as the witnesses talk to reporters from five different newspapers.

The Tribune version:

“Mrs. Lyons was about to retire for the night at 10 o’clock, according to witnesses….They were folding their chairs and preparing to go inside, witnesses told police, when two boys, about 14, approached them and began to talk. As they conversed, four older boys appeared.

“As the older boys approached them, one of the younger boys began to plead with Mrs. Lyons to give him her purse, or the older boys would beat him up, police said.

“When one of the older boys heard this, he kicked the young boy, police said. Mrs. Lyons told the attacker he should apologize to the boy, at which time one of the older boys pulled a small caliber handgun and fired the weapon into Mrs. Lyons’ face, police said.”

Building janitor Joseph Mendler ran outside after hearing the shots from his first floor apartment.

“I saw Mrs. Lyons lying on the ground,” Mendler told the Trib. “Blood was all over the place. I screamed and the neighbors called police. Her sweater was on the ground. I picked it up and put it under her head. She seemed to be alive. I felt so helpless.”

Mrs. Lyons was pronounced dead on arrival at South Shore Hospital. Her purse, stolen during her murder, contained less than $2.

“She couldn’t afford too much on her Social Security,” explained janitor Joseph Mendler. “She was trying to save up for a new apartment in Oak Lawn.”

The Daily News reports that police say “gangs of youths have been terrorizing elderly women in the area for some time.”

Mrs. Lyons and her neighbor were sitting in front of their building Sunday night, per the Daily News, when two girls and six boys, about 8 to 14 years old, walked up to them. Burnside Area Homicide Sgt. John Murtaugh told the News the same group of kids had “been roaming the neighborhood in recent weeks demanding candy from women.” Earlier that night, another building resident had given them some gum.

In the News version, as the kids talked with Mrs. Lyons and her friend, a smaller boy told Mrs. Lyons that an older boy had hit him. “The older boy said he did it because the other boy kicked him. Mrs. Lyons made the younger boy apologize. Moments later, the women picked up their chairs and walked toward a car in the parking lot to put them away.

“Murtaugh said the older boy then demanded the women’s purses. When neither woman would give up her purse, the boy pulled a small-caliber pistol and said he would shoot. Mrs. Lyons’ friend said she thought the gun was a toy cap pistol.

“The boy fired several shots, hitting Mrs. Lyons in the right upper chest, while another youth grabbed her purse.”

Mrs. Lyons’ friend screamed, and the kids scattered.

by Joe Ellis

“Police have arrested five Southside juveniles, ranging in age from 9 to 13, for Sunday night’s robbery and fatal shooting of 72-year-old Mrs. Helen Lyons,” writes the Defender’s Joe Ellis the next day.

Police say the .22-caliber gun that killed Mrs. Lyons was recovered from one of the older youths, and all five will be charged with armed robbery and murder in delinquency petitions. The children are being held at the Audy Home.

Chicago Daily News

by Larry Finley

“If Mrs. Helen Lyons had found that new apartment she had been looking for, things might have been different,” writes Larry Finley.

“But, she couldn’t find anything she really liked that she could afford. So she decided to stick out another winter in the apartment building at 7601 South Shore Dr. where she had lived for eight years.

“Sunday night, Mrs. Lyons, 72, was shot to death by a boy hardly old enough to be out of grade school.”

Finley reports that a group of seven to eight youths “had been shaking down the elderly residents of the quiet South Shore neighborhood for payoffs of candy and change.”

Finley tells the same basic story of the shooting, then turns to building janitor Joseph Mendler.

“I took the trash out about 9: 15 p.m.,” he says. “The ladies were sitting out there on the grass on folding chairs. They sat there in the evening. Lots of people used to, but they don’t anymore.”

“Mendler calls the neighborhood ‘integrated.’ Others use the word ‘changing,’” writes Finley.

This is our second indication that Mrs. Lyons’ murder is part of a current spate of white crime victims/Black assailants in previously all-white South Side neighborhoods which are now partially integrated or mostly Black. This closely follows a spate of Black families whose homes have been attacked after moving into all-white neighborhoods.

The first indication that Mrs. Lyons was a victim of this vicious cycle was the fact that the Defender covered her story, because the Defender doesn’t cover white victims unless Black people are somehow involved.

The interesting part of the coverage of Mrs. Lyons’ death is that none of the papers mention that she’s part of this racial pattern, even though the papers explicitly discuss the situation in other cases, including Joseph O’Shea (July 28, 29, 30), Kathleen Fiene (June 21, 22, 23), and Peter La Rocca (August 4). The Tribune recently ran a two-part series on the phenomenon. See Julia Honchar’s “No Welcome Mat Out When Blacks Move In” on July 9, and “Why Whites Leave, Stay in Changing Areas” on July 10. See May 25, May 26, May 27, and May 28, and July 10 for more on cases of Black families attacked in white neighborhoods. Chicago Today examined the issue on June 4.

Finley still doesn’t mention the race of Mrs. Lyons or the kids, and neither does any other account over several days in any newspaper—again, a distinct break from all previous coverage of similar crimes. In 1972, the papers can safely assume readers of all backgrounds know South Shore is undergoing racial transition, recognize the likely ethnic provenance of Mrs. Lyons’ name, and draw their own conclusions.

“Few people in the area want to talk about the growing crime problem,” Finley continues. “Mendler didn’t want to talk about it again Monday, but finally he opened up.

“‘I have to call the police almost every night because of trouble,’ he said. ‘About 10 or 11 p.m. is worst.’”

Mendler first says crime rises in summer, since the building is on a dead end leading into Rainbow Beach. He gradually recalls other recent muggings and beatings, then says it’s bad in winter too, because “it gets dark early and a lot of people have to walk home from the CTA stop.”

Finally, Finley reports that investigators were tipped off by the grandmother of one of the accused boys, who called police when she thought her grandson was involved. The younger children all admitted being at the scene of Mrs. Lyons’ death, but said a 13-year-old shot Mrs. Lyons. “The 13-year-old denies being there at all.”

Later in the week, the Daily News will report the kids told police they got the gun that killed Mrs. Lyons by breaking into a parked car at Colfax and 75th, where they found three guns and ammunition.

Only the Tribune runs a picture of Mrs. Lyons, on August 22.

August 23, 1972

Every Chicago Paper That Existed in 1972

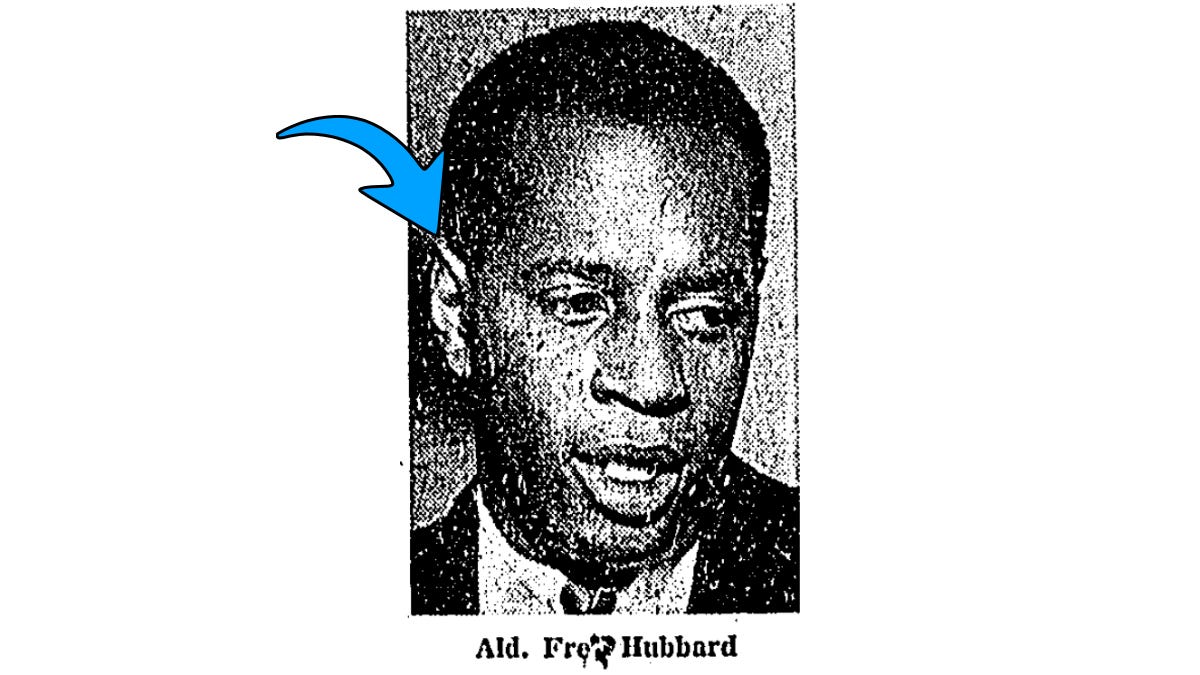

Remember 2nd Ward Ald. Fred Hubbard, who disappeared in 1971 along with $100,000 from the Chicago Plan for Equal Opportunity, the federally-funded program Hubbard ran charged with placing minorities in construction trade jobs?

Hubbard is finally ba-a-a-ck.

The money is not.

As a Tribune article neatly summarized when Hubbard vanished over a year ago:

“A United States Labor Department grant of $567,000 [~$4 million in 2022] was used to set up [the Chicago Plan] in 1970 after a group of 61 black community organizations shut down $80 million worth of construction projects to focus attention on their demands for greater representation in the city’s 19 building trades unions…. Government officials have criticized the plan for failing to live up to a goal of 4,000 new jobs for blacks in the building trades during the first year.”

The Chicago Plan was supposed to increase minorities in the trades by cooperating with the unions, rather than instituting federal quotas—though quotas were being used in Philadelphia according to several reports.

How close was the Chicago Plan to that 4,000-job goal? At that time, Hubbard told the Defender there were 65 Chicago Plan people studying to become operating engineers, while 48 people were enrolled in a welding course—of whom two had graduated and gotten jobs.

So Ald. Fred Hubbard was not doing a bang-up job at his job as director of the Chicago Plan—or perhaps he did all anyone could. Some speculate nobody, including Hubbard, ever thought the Chicago Plan could possibly work—that the whole thing was a cynical ploy to quell the pressure for better minority representation in the trades.

A Daily News “Insight” article by Les Hausner this week will note that “Hubbard had an impossible assignment—making it work—and many knew this. He had no false notions about the problems of convincing unions, many with unemployed members, to take on more minority workers.”

Either way, Hubbard and a whole lot of money disappeared simultaneously.

In our 1972 timeline, Hubbard’s former aldermanic campaign manager won the special election held last week to fill the empty 2nd Ward City Council seat.

“He had everything going for him and he blew it—for nothing,” new 2nd Ward Ald. William Barnett tells Chicago Today for today’s edition, after learning that Fred Hubbard is now in federal custody.

Time to tell the Fred Hubbard story, such as we know it. Buckle up for Mr. Hubbard’s Wild Ride.

If you’d rather skip directly to this week’s 1972 Fred Hubbard news, scroll to the next “August 23” headline or click here.

The basics, some necessary vegetables that will nourish our understanding of Fred Hubbard as we go on:

Fred Hubbard’s family came to Chicago’s South Side from Beaumont, Texas when he was one year old. He dropped out of DuSable High School at 16, according to Les Hausner’s Insight article, then enlisted as a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division at 18 for a five-year stint, earning his GED during that time. Hubbard entered the University of Chicago on his return, graduating in 1958.

Per Hausner, Hubbard “made good use of his poker-playing skills to help finance his college education”.

The Daily News reports Hubbard headed the UC campus NAACP chapter. Later, Hubbard ran a South Side SNCC chapter and “participated in the Montgomery (Ala.) bus boycott, and in the Selma (Ala.) freedom march.”

According to Hausner’s “Insight,” Hubbard started as a teacher at Wendell Phillips High School before heading the YMCA’s Program for Detached Workers, “a citywide effort to curb delinquency among teenage gangs,” in 1961.

By the time Hubbard ran for 2nd Ward alderman in 1969, he headed the Clarence Darrow Community Center, a social service agency started originally by the Unitarian Church in the CHA’s LeClaire Courts on the Southwest Side—along Cicero just south of the Stevenson Expressway. The Darrow Center later became part of Hull House. Hull House (the social service organization, not the museum), the Clarence Darrow Center, and LeClaire Courts are all gone in 2022.

In short, Fred Hubbard was a textbook example of an up-and-coming progressive independent, with impeccable credentials. That and 42 cents would get you a cup of coffee in Mayor Richard J. Daley’s 1969 Chicago. (That coffee would cost $2.83 in 2022 money—cheaper than Starbucks, more than Dunkin’ Donuts.)

So it was absolutely shocking when Fred Hubbard won the 2nd Ward City Council seat that year by beating the Democratic Machine candidate, hand-picked by Black South Side political powerhouse U.S. Rep. William L. Dawson.

But 1969 wasn’t Hubbard’s first race. First, Fred Hubbard went after Dawson himself in 1966. This was, essentially, like trying to slay a dragon with a BB gun.

Bill Dawson started out in politics as 2nd Ward alderman himself—a Republican alderman, 1933-1939. Dawson lost that office along with Republican backing after unsuccessfully challenging his mentor, Oscar De Priest, for the Congressional seat he would eventually win. Dawson returned to politics as the new Democratic Commiteeman of the 2nd Ward—thanks to then-Mayor Ed Kelly and the still young Machine.

This was the early 20th century, when Blacks as a group were moving from the historical party of Lincoln to the more liberal social policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Democrats. In 1943, Machine Democrat Bill Dawson moved on to Congress.

Dawson served 27 years in the House of Representatives, becoming the first Black chairman of a standing committee in 1949. The 2nd Ward remained at the heart of the Black sub-Machine Dawson built within the larger city-wide white Democratic Machine. Dawson died in 1970, soon after handing off his seat and the reigns of the Black sub-Machine to then-3rd Ward Ald. Ralph Metcalfe. (Regular TCD1972 readers know Metcalfe as the powerful U.S. representative who has recently broken with Mayor Daley in our 1972 timeline over the issue of police brutality in Black communities.)

Throughout the 1960s, aging Rep. Bill Dawson’s power waned as a new wave of Black politicians rose who focused on civil rights and loudly opposed the reigning political powers, including the Machine.

Still.

To put Dawson’s power in perspective, he took a large slice of the credit/blame in 1955 when the Cook County Democratic Central Committee refused to endorse incumbent Mayor Martin Kennelly for a third term—and backed Richard J. Daley instead.

Also: After Dawson’s 1970 death, Tribune columnist Vernon Jarrett wrote about his first encounter with the Congressman as a “fledgling reporter,” still new to town. It was 1946, when Republicans won offices across the state and Cook County in a mid-term election—but Dawson’s wards still delivered the Democratic vote. Young Vernon Jarrett asked Rep. Bill Dawson how he’d done it.

Dawson was amused. “Just print in your little story that Bill Dawson’s machine rolled again,” he told Jarrett. “That’s right, I said machine,” Dawson added when Jarrett gave him a horrified look. “Because that’s what I’ve got. And it’s the best machine—white or Negro—in this country.”

That kind of machine takes a long time to wane.

Political neophyte Fred Hubbard didn’t stand a chance against Bill Dawson’s machine in 1966, but it was a lively primary race.

In May, Hubbard was shot in the shoulder by a mysterious gunman. Hubbard said the man showed up late one night at the campaign office at 3506 S. Michigan. (That site is now part of the new main Chicago Police headquarters.)

“Hubbard, 36, told police he was alone at a desk in his small personal office when the man walked into the darkened front office and fired a shot from the doorway. The bullet struck Hubbard in his left shoulder.

“Hubbard pulled a .38-caliber pistol from a desk drawer and fired twice at his attacker before the man escaped through the front door.”

Hubbard said he couldn’t give police a good description of his assailant, since the room was dark. “He could only describe the man as a Negro, of ‘average’ size, probably in his 30s.”

“Why would anyone want to have a gun down here on 35th St.?” Rep. Bill Dawson told the Daily News’ Edmund J. Rooney the next day. “You need a gun over in Viet Nam, not out here….I don’t have a gun. Never have, either. And if anybody wants to kill me, they can any time they want.

“Look, I’m the most powerful Negro congressman in the country, and I don’t need a gun.”

Dawson offered a $5,000 reward for the gunman. Supporter Dick Gregory visited Fred Hubbard in the hospital, and offered a $10,000 reward, but even $15,000 didn’t solve the case. Dawson rolled over Hubbard in the 1966 primary.

But Hubbard came back for more.

The next year, he ran for 2nd Ward alderman against 24-year Machine incumbent and Dawson-backed William Harvey. Hubbard lost, by about 1,500 votes—which is a lot, but perhaps not as much as you might expect from a well-oiled sub-Machine.

When Cook County Board President George Dunne appointed Ald. Harvey to an open Board seat, Hubbard ran in the 1969 special election to replace him. Hubbard ran against Dawson administrative aide Lawrence C. Woods, and as we know, Hubbard won.

But how did Fred Hubbard finally beat U.S. Rep. Bill Dawson, the most powerful Black Congressman in the country, who Vernon Jarrett referred to as “The Man,” and in Dawson’s own ward?

It doesn’t tell us anything about where that $100,000 of Chicago Plan money went, but it sure is interesting. It also illustrates the enormity of the Fred Hubbard scandal, particularly in the Black community.

As we’ve seen, Hubbard had compiled a work record that simultaneously gave him solid professional credentials, and got him out in the community working and mixing with potential constituents. Hubbard had also been actively involved in Chicago civil rights circles, and he’d been working to create an anti-Dawson organization of his own since that 1966 primary challenge.

Hubbard may not have had a lot of close friends, as many people averred after he disappeared, but the friends Hubbard did have were just the right kind.

Like legendary Chicago political operative Don Rose.

Before Don Rose managed Jane Byrne’s historic winning campaign to overthrow the Chicago Machine by beating Mayor Michael Bilandic in 1979, he was good friends with Fred Hubbard, and a key part of Hubbard’s 1969 aldermanic campaign.

Hubbard drew terrific press in his 1969 aldermanic run, both due to his contacts including those via Don Rose, and because Rep. Bill Dawson made an absolutely horrible choice when he put Lawrence C. Woods up for the 2nd Ward seat.

In 1969 Chicago, no candidate could get better press than a Mike Royko column eviscerating his opponent—unless it was three Mike Royko columns eviscerating his opponent.

Don Rose was friends with Mike Royko. Don doesn’t remember anymore whether he first put Royko onto Fred Hubbard and his awful opponent, Lawrence C. Woods. It could have been Royko’s good friend and fellow Daily News reporter Lois Wille, says Don, because she lived at the time in the 2nd Ward, in one of the two integrated high-rise developments that had gone up on King Drive—Lake Meadows and Prairie Shores. Hubbard, we’ll learn later, lived in Lake Meadows at 601 E. 32nd Place.

Either way, “We kept feeding him [Royko] stuff as we went on,” says Don.

Oh, that first Royko column on Lawrence C. Woods from January 31, 1969 is a doozy. Even for Mike Royko, the lede is astonishingly delicious:

The Hot Springs chief didn’t remember Woods ever having what you’d call a job, Royko went on. And Woods got arrested in Chicago in 1959, while working as an appraiser for Cook County Assessor Parky Cullerton.

Police set up a sting operation after a businessman reported that Woods shook him down for $200 for a lower real estate tax assessment. They caught Woods with $200 in marked bills, which got him a grand jury indictment for malfeasance and bribery. But somehow—because Chicago, as the Chicago History Podcast would say?--Woods got acquitted by a judge after “police told conflicting stories about the arrest”.

Royko covers what one would think must be every sordid detail of Lawrence C. Woods’ history in Chicago. Eventually, because Parky Cullerton would not take him back into the Assessor’s office, Woods ended up working for Bill Dawson—“political ruler of the South Side,” as Royko describes the congressman.

“Dawson needed a hatchet man, somebody who could purge people from the organization, vise (fire) them from patronage jobs, lean on them for contributions,” a former 2nd Ward worker told Mike. “If there is anything Woods is good at, it is being a hatchet man.”

And now Mike Royko gives us a potential answer for the nagging question of why powerful, canny Machine boss Bill Dawson would make such a terrifically bad choice for the 2nd Ward aldermanic candidate:

The aging and ailing Dawson, wrote Royko, needed Woods more and more to handle the unpleasant political tasks he could no longer handle himself.

“Woods leads Dawson around, buys his clothes for him, and happily gobbles up more and more of the political powers,” wrote Royko.

Royko concluded by describing Fred Hubbard, “a University of Chicago graduate who earns his living working with juvenile street gang,” and what would happen if Hubbard didn’t win:

“If Hubbard doesn’t muster enough strong independent support to offset the patronage army and organizational bankroll, Woods will take a seat in the City Council.

“And there he will help guide and shape the destiny of this, the nation’s second largest city.

“Boy! Some town, huh?”

Mike came back to Lawrence C. Woods on February 18. This time, Mike noted that Woods, “police record and all,” wanted “people to believe the ward’s leading citizens like him and are clamoring for his election.”

Thousands of pieces of Woods campaign literature had been stuffed in 2nd Ward mailboxes, per Royko, all featuring endorsements from prominent local businessmen, professionals, civic leaders and organizations. Mike’s phone survey found a lot of alleged Woods endorsers didn’t even know the candidate, or hadn’t endorsed him. That included the biggest name in Black Chicago business at that time—John Johnson, head of Johnson Publications. See here and here for the 1972 grand opening of Johnson Publications’ new headquarters on Michigan Avenue.

On March 19, the Daily News ran a lengthy editorial backing Fred Hubbard for 2nd Ward alderman. It almost doesn’t matter what the editorial said. The Daily News just did not normally dedicate stand-alone editorials for aldermanic races.

An excerpt:

Wow.

Hubbard was also backed by the Better Government Association and the IVI. He was running that year along with fellow progressive Bill Singer, in 1972 the most famous alderman in town for getting Mayor Daley and the elected Machine delegation kicked out of the Democratic National Convention. It gives one pause, at this point, to consider how Bill Singer’s and Fred Hubbard’s paths diverged between 1969 and 1972, a mere three years.

Hubbard and Singer were both supported by prominent independents like U.S. Rep. Abner Mikva, plus the City Council’s small independent bloc including legendary 5th Ward Ald. Leon Despres and independent Black aldermen William Cousins and A.A. “Sammy” Rayner.

Plus, there came an almost unprecedented third Royko column on Lawrence C. Woods.

On February 27, Mike talked to William Hall, the guy who complained that Lawrence C. Woods tried to shake him down for $200 to lower his tax assessment.

“He wanted me to sign some papers exonerating him,” Hall told Mike, and per Royko, Hall was “laughing as if it were the funniest thing he had ever heard.”

Hall said Woods came to his house with official papers all drawn up. “He told me that if I signed them, and he was elected, he’d do everything he could for me,” Hall told Royko.

Hall also told Royko he was not going to sign the papers.

Fred Hubbard’s campaign benefited from his Royko coverage in many ways, as this letter to the Daily News shows:

Finally, Daily News political editor Charles Nicodemus investigated and found that Woods “owed Illinois thousands of dollars in sales taxes” collected at gas stations he owned.

County and state records showed Illinois hit Woods with $15,280 in property liens over the unpaid sales tax, and the Illinois secretary of state’s office tried to dissolve his corporation for not paying its 1968 franchise tax.

Woods refused to comment.

“We even had some regular Democratic precinct captains who thought he [Woods] was so bad that they helped us,” Don Rose remembers.

Today, Don acknowledges that Hubbard’s 1969 win wasn’t quite on the level of Jane Byrne kicking the Machine’s ass in 1979. But to beat Bill Dawson’s machine, in his own ward, even with a ghastly candidate like Lawrence C. Woods, was still a marvelous achievement.

“We were obviously surprised,” says Don modestly. “It was quite exhilarating.”

“This is the biggest possible defeat the Democratic Machine could have suffered,” Ald. Leon Despres declared at the time. “The 2nd Ward always has been the most secure position of the Machine.”

Lois Wille wrote the Daily News’ Fred Hubbard victory party article on March 12, 1969. Hubbard won 6,942 to 4,599. It was the first time since Mayor Daley took office in 1955, Wille noted, that “a big, low-income black area voted against the regular Democratic organization.”

Hubbard’s tiny storefront campaign office at 35th and Michigan, she reported, crammed with about 300 people, “nearly blew apart with cheers and tears.”

“Women from the housing projects wept, old men with straggly beards giggled and couldn’t stop, ex-gang leaders in goatees hugged each other,” wrote Wille. “Their man had done it. Fred Hubbard, 40, a lanky social worker, had beaten the once-awesome Dawson machine.”

“‘Do you know what this means?’ asked Mrs. Lucille Hill, of 2250 S. State, in the Harold B. Ickes public housing project. Tears were streaming down her cheeks and her hand was trembling as she tried to wipe them away. ‘It means we’re independent. It means nobody’s going to tell black people how to vote anymore.’”

The Hubbard victory party expanded into a small theater next door to the campaign office, and finally about 1,000 people crowded into an even bigger party at the Concept Ballroom, 7917 S. Halsted, which is now a parking lot next to a liquor store.

The quieter contingent of Woods supporters at their headquarters, wrote Wille, said “their man lost only because of a ‘dirty’ campaign. They placed much of the blame on The Daily News”.

But Fred Hubbard shocked everybody all over again the minute he hit the City Council floor.

At Hubbard’s very first Council meeting, he voted against the independent City Council bloc, which had so ardently supported his campaign. Hubbard’s votes with Mayor Daley included defeating Ald. Leon Despres’s attempt to allow TV news cameras into Council meetings, and a resolution to ban anti-ballistic missile sites in Chicago and other population centers.

“I never aligned myself with anyone,” Hubbard told the Tribune’s Michael Kilian afterward. “I ran as an independent. I am not a member of the liberal bloc, or any bloc.”

“He ratted on the very first vote he had,” Don Rose recalls now.

Hubbard had resigned as director of the Clarence Darrow Center when he entered the Council—though the job of alderman is technically part-time, and most aldermen held outside jobs. Lo and behold, Mayor Daley soon appointed Hubbard to head the Chicago Plan for $25,000/year—which is $168,750 in 2022 money. A nice gig.

For obvious reasons, Hubbard was quickly considered a Machine alderman.

“By the summer of 1969—-just a few months after he was elected—it became obvious that Fred wanted to join the Organization and could not be considered as an independent,” Don Rose told the Defender after Hubbard disappeared in 1971. “We never had sharp or harsh words…but there was an amicable parting of our ways.”

Rose also told the Defender that Hubbard would never have gotten the Chicago Plan job if he was still an independent alderman.

“The Chicago Plan in my estimation was at best a bad compromise and possibly a kind of fraudulent public relations gimmick,” Rose told the Defender, yet he still believed Hubbard had good intentions: “But Fred’s view was that he was going to make it work; he was going to get jobs for blacks.”

Like so many others in 1971, Don Rose found it almost impossible to think ill of Fred Hubbard.

Mike Royko did not endorse Hubbard when he ran for re-election in March 1971.

The only question was whether Hubbard made the decision to turn Machine after he was elected, or before. When veteran Tribune reporter Robert Davis reports on Hubbard’s sentencing in 1973—spoiler alert, Hubbard is guilty—he will write: “Altho he ran as an anti organization candidate…Hubbard had the secret support of Mayor Daley, who soon made Hubbard an organization alderman.”

Don Rose still has no idea what the true answer may be.

“I can’t say,” he muses. “It’s possible that some of the Machine precinct captains who switched over to support him talked him into it— ‘We’ll guarantee you the office, but—’. Something like that. I really gave up trying to figure that one out.”

Either way, everybody figured the Chicago Plan job was Hubbard’s reward.

If so, the Chicago Plan was not rewarding enough.

In 1971, Fred Hubbard shocked everybody a third time.

By late May 1971, nearly $100,000 of Chicago Plan money had disappeared. A Cook County investigation got underway first to see if the funds had disappeared into Hubbard’s pocket. Considering the situation, the Defender called Hubbard “the loneliest man in his ward”.

Defender reporter Pierre Guilmant wrote that Hubbard’s constituents presumed he was guilty, “because he is dis-liked” and “resented” for running as an independent and then joining the Daley Machine.

Note: Readers would read many differing accounts of the views of 2nd Ward constituents regarding their errant alderman. And it could be that that each account was correct, at the time.

“Federal Bureau of Investigation agents and Labor Department examiners yesterday joined State’s Atty. Edward V. Hanrahan in the investigation of the forging of $70,000 in checks from the funds of the Chicago Plan,” wrote Ronald Koziol and Thomas Powers in the Trib on May 22, 1971.

Per that report, the Chicago Plan’s secretary-treasurer Thomas J. Nayder, “who also is president of the Chicago Building Trades Council…discovered the forgeries late Thursday when a check for $54,000 was returned from a bank marked insufficient funds….An aide to Hanrahan said investigators want to talk with Ald. Fred D. Hubbard [2d], who is director of the program, to see if his signature also had been forged. The signatures of the two men are required on each check. Hubbard did not appear for the City Council meeting yesterday and could not be located at home or at the office.”

“Nayder said that in addition to the forging of his name, monthly bank statements kept in the Chicago Plan office…had been doctored to hide the full amount of checks written.”

The Defender’s Charlie Cherokee column included a prescient but completely wrong item on May 19, 1971:

And yes, Younger Readers, the Defender ran a social/political gossip column called “Charlie Cherokee Says,” starting in the 1940s. See this January 4 item for some background.

By the end of May 1971, Hubbard hadn’t been seen for two weeks. The Defender led in reporting theories of his whereabouts.

On May 29, the Defender reported that “sources close to the investigation” said one person couldn’t have pulled off the fraud alone, but Hubbard was still the key.

“Hubbard is reported to have had at least five different checking accounts around the city—all of which are presently overdrawn,” wrote the Defender in a page one, unbylined article. “Underworld figures report a ‘credit check’ was run on Hubbard by Las Vegas members of the syndicate and he was ‘approved as a good risk’ by the Chicago syndicate members of the juice rackets. They also report Hubbard may have borrowed considerable funds from the syndicate just prior to the discovery of the embezzlement.”

“Missing Ald. Fred. Hubbard [2d] borrowed money from other employes of the Chicago Plan and spent large sums on a 20-year-old girl friend who went to Las Vegas with him on a gambling trip, THE TRIBUNE was told yesterday,” graced the front page of the Tribune on May 29.

“Hubbard is being sought on a federal warrant charging fraud for allegedly converting $20,000 of plan funds to his own use,” the Trib’s Jeannye Thornton and Gerald West reported. “Meanwhile, a Cook County grand jury yesterday heard eight witnesses…in the first day of an investigation into missing funds from the plan that may total $95,000.”

Hubbard’s alleged girlfriend, Camille Landry, shared an apartment at 5325 S. Cottage Grove with a talkative roommate, Judy Christopher. The Trib identified Landry as an unemployed former public relations staffer at Malcom X College.

Judy Christopher “told THE TRIBUNE” that Ald. Hubbard and her roomie had been dating for almost a year, and “that Hubbard often took the two women to expensive restaurants and bought Miss Landry clothing in hotel dress shops. Miss Christopher said Miss Landry told her that she and Hubbard often went to race tracks.”

Per Judy Christopher, Landry “had a confrontation Saturday with Hubbard’s wife, Arnette, who knew about her husband’s relationship with Miss Landry. The two women argued when Mrs. Hubbard went to the Cottage Grove apartment to get money for Hubbard’s defense”.

The Tribune reached Camille Landry for the May 29, 1971 edition by phone, at a Mexico City hotel. Per the Trib, Landry claimed to be on vacation. Later, Landry would say she was tired of Chicago racism and wanted to check out Mexico. The paper calls her “alias Camille Dennis” —readers will later learn she traveled to Mexico under using her middle name for a surname.

Landry called herself “an innocent bystander” and denied receiving any Chicago Plan money, or knowing Hubbard’s whereabouts. She insisted she was willing to return to Chicago for any subpoena or warrant.

By the Tribune’s May 30th edition, roomie Judy Christopher had “reportedly told the grand jury” about Hubbard’s gifts and trips to Vegas. The Trib updated its phone conversation with Camille Landry, who wasn’t pleased with her ex-roommate:

“Judy was in no way incriminated in any of this and why she would go off on a limb like that to perjure herself and lie against me, creating a heap of trouble for me, I don’t know,” Landry told the Trib.

The Trib sent Latin America correspondent Barry Bishop to Mexico City to interview Landry. She’d been “advised by legal counsel not to return to Chicago at this time” and said she planned to stay in Mexico to work with some photographers she’d befriended. Landry told Bishop she’d done some work for Hubbard, who paid her $120 on May 12—the last day Hubbard was seen in Chicago.

Correspondent Bishop also provided a strange amount of detail on Camille Landry’s outfits.

By June 2, readers learned that Cook County had a warrant for Landry’s arrest for “theft of more than $150 from the Chicago Plan job program.” The Trib now identified Landry as “a Chicago free lance writer and photographer,” and reported Landry said Hubbard paid her for photographing black construction workers.

What about Fred Hubbard himself?

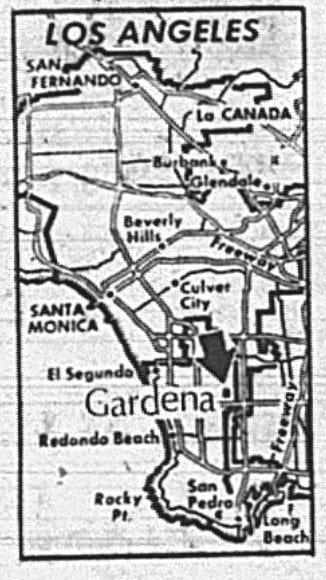

“Authorities said Hubbard was last seen May 25 leaving a Los Angeles suburb in a rented car. The car has not been found. Before this he spent six days in Las Vegas casinos, where authorities say he gambled heavily and lost.”

Finally, Hubbard was officially indicted by the Cook County grand jury on June 2, 1971 for forging 12 checks totaling almost $100,000 through May 5, 1971.

“The May 5 cutoff date in the alleged scheme was two days before Hubbard, 42, made the third of four known trips this year to a Las Vegas gambling casino, where authorities say he lost heavily,” reported the Trib.

A federal grand jury was about to convene.

At that point, the Defender reported, authorities were searching for a car Hubbard “is alleged to have ‘borrowed’ from Mrs. Octavia L. Miles, a former worker in Hubbard’s political campaigns, and currently a resident of Redondo Beach, Calif.

“According to Mrs. Miles, Hubbard called her ‘apparently from Las Vegas’ asking for $50 for plane fare. She said she sent him the money and later met him near her home. She said Hubbard ‘looking like a man down on his luck’ spent the night in her home. The following morning…Hubbard ‘borrowed’ her rented car and hasn’t been seen by her since.”

By the end of June, 1971, Fred Hubbard’s strange saga only rated page three in the Trib for this:

A Hertz employee found the car with the key in the ignition, left there two weeks earlier. Reports that Hubbard was hiding out in Panama City couldn’t be confirmed.

The Chicago Plan offices closed. The employees were laid off a few days later. By the end of summer 1971, a federal grand jury indicted Hubbard on 16 charges of embezzlement for $100,715, for 15 forged checks.

Camille Landry returned from Mexico, was arrested, testified before the Cook County Grand Jury in exchange for immunity, and by fall ‘71, her charges were dropped. Landry told reporters she’d been Hubbard’s “girl friend” for one year, and last saw him May 19:

“He came to my home. We had a lot of company there. He stayed about five minutes and didn’t even take his coat off.”

The press reported public opinions on Hubbard across a board the size of a continent.

The Tribune’s Jeannye Thornton and Gerald West gathered a sampling of 2nd Ward residents.

“I believe it was some kind of frame-up,” said King Collier of 3615 S. Federal.

Mrs. Ethel Leathart, 3640 S. King, perhaps best illustrated the conflicted feelings of many:

“I think Ald. Hubbard is a good man and I don’t think he should come back. I think he should go to a foreign country and hide. If he should come back, he shouldn’t have one quarter in his pocket. The courts will give him a good public defender. All I can say is: Fred, wherever you are, take the money and run, brother, run.”

From the Defender’s letters section, June 2, 1971:

But hope that Hubbard was innocent began to fade. The Defender ran this front page story on June 16, 1971:

Hubbard’s friends were quietly admitting he was probably guilty, reported the Defender, and “busily marshalling support for his legal defense and, at the same time, are trying to convince Hubbard that he should come forward and get his wife, family and friends off the hook.”

These friends and “sources close” to Hubbard told the Defender it all started with “the ‘misappropriation’ of a mere $2,000 for the alderman’s personal use.”

Note: That’s $13,500 in 2022 money.

“With all the sincerity a gambler’s psychosis could muster, Fred Hubbard intended to replace that money. That was why he ‘misappropriated’ another $5,000 to lay on the poker tables of Las Vegas. The gamble didn’t pay off and Hubbard was then faced with a $7,000 deficit.”

Almost $50,000 in 2022.

“The gambling fever is consuming, psychologists and gamblers say. To Fred Hubbard, at this point, the fever for gambling was suddenly replaced with the fear of getting caught, and the thousand natural thoughts that with just one more stake, all would be well and no one would be the wiser.

“That was when Hubbard allegedly forged a Chicago Plan check in the amount of $20,000. Two days and $27,0000 later, Hubbard returned to Chicago, shaken, frightened and caught up in the irrational ‘break-even sickness’ to which gamblers are heir, especially when they know their losses can get them into serious trouble.

“The pattern continued— ‘borrow and lose’ — until the grand sum of $98,000 had been appropriated and lost to the plush table of Las Vegas’ strip.”

Let’s remember, in 2022 money, that was $661,500.

On June 8, the Defender’s Ted Lacey talked to Don Rose, who remembered Hubbard as a friend who attended a weekly poker game. Hubbard was “a loner who had trouble asking for help,” Don recalled—a description echoed by others in various reports.

“There were five or six of us involved in that weekly poker game for about five years,” Don told Lacey. “For some reason each of us seemed to be going through some sort of personal crisis during those years. We all considered the poker game—which usually met over at my house—to be the one fixed point in our lives during that troublesome time.

“Hubbard then faced the pressures of finishing college work at the University of Chicago, which were compounded by the birth of his first child and the divorce from his first wife, and then a remarriage and launching into his first major job.”

“It was a very strict game we ran. We would play from 8 p.m. to midnight and stop on time so nobody could complain about wanting to play an extra hand to win back his losses,” Rose continued. “The stakes then were such that you could win or lose from $20 to $50 a game. Fred would consistently be the big winner every week.”

The games broke up in the early ‘60s, said Don, when Fred went on to games with higher stakes that Rose couldn’t manage.

“Fred was the best poker player I’d ever seen at that point, but I suspect he moved on to games with higher stakes and eventually couldn’t handle it economically,” Rose told the Defender. “A good poker player has to know how much money he is capable of handling. If the stakes get too big, you start playing differently, and I think that’s what may have happened to Fred.”

Today, in 2022, Don Rose says that article “still holds up.” He would tell the Fred Hubbard story exactly the same way now.

Why do you think he did it, I asked.

“Greed,” said Don. “I didn’t see it coming.”

As we already revealed, Fred Hubbard was guilty, though he initially pled not guilty. It wasn’t really much of a spoiler, right? We’ll cover the details of how Fred Hubbard was found, his life on the run, and the days that followed his capture, further on in today’s post and in future editions of TCD1972. But in a few months, Hubbard will plead guilty to “all 16 counts of a federal indictment charging he embezzled $100,715 from the Chicago Plan,” per Robert Davis’s report in the Tribune.

Hubbard will be sentenced to two years in prison, with four years of probation including a Gambler’s Anonymous program. That was a good deal, worked out by Hubbard’s attorneys. The maximum penalty would have been 151 years in prison.

“Mr. Hubbard, this distresses me personally,” Judge Hubert L. Will told Hubbard after passing sentence. “I think reform politicians should not double-cross their constituents.” Now that’s Chicago.

So many people had held on to believing in Fred Hubbard for so long. Tribune columnist Vernon Jarrett, for one, was clearly bitter.

Just after Hubbard’s sentencing, Jarrett wrote about attending a 1969 political meeting in a Wentworth Gardens apartment, where he met “two courageous blacks” who believed in Fred Hubbard as he ran for alderman.

“One of them was on welfare and the other was a city employe,” wrote Jarrett. The two women left the meeting early to ring doorbells for Hubbard in Robert Taylor Homes. “It was no secret that it took a lot of courage for people in their economic position to fight the big man on the 5th floor of City Hall,” wrote Jarrett.

Besides the wide array of support Hubbard attracted across the progressive spectrum, Jarrett continued, “add to his followers the thousands upon thousands of pride-hungry, spiritually desperate black people who want to believe that somewhere there are public figures who are singularly committed to ‘our liberation.’”

“The public must trust somebody or withdraw from the political scene,” wrote Jarrett. “Hubbard knew that. A good con man with talent and a good flow of words has a waiting audience among the desperate.

“That’s why I would not have wept a fraction of a second if Judge Hubert Will had given him the maximum sentence.

“Hubbard’s crime must be classed with that of a dope peddler….He absconded and gambled with something too precious to fritter away at a Las Vegas dice table: the faith and hope of thousands of poor, desperate black people.”

I wondered what it would have been like for Don Rose to meet Fred Hubbard again, after Hubbard double-crossed the people who put him in office, then disappeared with $100,00 of public money.

“I saw him after he got out of jail, and he was driving a cab,” said Don. “It was as if little had happened. ‘How are you, what are you doing now.’ In fact, he flagged me down. He was in a coffee shop or something and saw me passing by, and he ran out to grab me— ‘Haven’t seen you in a long time.’ But we did not discuss any of his…peccadilloes.”

Fred Hubbard would sadly go on to one more act in the public eye, before dropping from sight. He did drive a cab initially after leaving prison. But in 1985, he assumed the identity of a recently-deceased college acquaintance to get a job as a Chicago Public Schools substitute teacher for $42/day. The ploy was exposed a year later when Hubbard, then 57, was accused of making an “obscene proposition” to a 13-year-old student. I assume the charge was somehow dismissed, because the case never made the papers again.

After his capture, Fred Hubbard repeatedly claimed he was writing a novel, clearly based on his experience. At one point, one of his lawyers said he’d read some of it and thought it could be a best seller, while admitting he was not a literary critic. But the book never came to pass.

Fun Fact: Just one of Hubbard’s fellow freshman alderman from 1969 remains in Chicago’s City Council, as this is freshly posted in 2022. Here’s an excerpt from the Tribune’s January 7, 1969 round-up on that election:

Ald. Ed Burkę had no trouble beating the Republican Ed Burke from 1969, or his other six opponents. Or anybody else since. We already noted how Fred Hubbard’s path diverged from Ald. Bill Singer’s within three short years. What happened to Ald. Ed Burke in 53 years?

Ald. Burkę has often been called the most powerful alderman in the Council, because he indisputably was exactly that as chairman of the Finance Committee—from 1983 to1987, and then 1989-2019.

But how did Ald. Burke lose the Finance chairmanship in 2019, after surviving scandals including his share of ghost payrollers in the 1990s federal Operation Haunted Hall investigation; decades of blatant conflict of interest by helping law clients reduce their taxes; and his embarrassing grilling of talk show host Jerry Springer in a nationally-watched 1999 City Council committee hearing, during which the most incriminating information Springer gave up was that he lived at the John Hancock?

Ald. Burkę resigned his Finance chair after being indicted on 14 counts of racketeering, bribery and extortion. He goes on trial in 2023.

If Ald. Burke is convicted, the wildly divergent paths he and Fred Hubbard have taken through life will suddenly cross once more.

And Fred Hubbard’s name will pop up in the papers again, because that’s how it always appears. Both surviving newspapers—the Sun-Times and the Tribune— run a “Hall of Shame” list of convicted aldermen every time a new colleague joins the club. For some reason, that list always begins in 1973, the year Fred Hubbard will plead guilty.

Thus Fred Hubbard is, in this one arena, always Number One. ***

What else.

Fred Hubbard’s spouse in 1972, attorney Arnette Hubbard, shed the adjective “wife” and then “ex-wife of ex-Ald. Fred Hubbard” quickly and went on to a long, illustrious legal and political career. Less than 10 years after Fred Hubbard’s debacle, Arnette Hubbard would serve as president of two Black legal groups—first the Cook County Bar Association and later the National Bar Association. She would run unsuccessfully for a state senate seat, then get appointed by Mayor Harold Washington to the city’s cable commission, and later the Cook County Elections Board, before taking a seat as a Cook County Circuit Court judge. Her name pops up continually in the Chicago Daily Defender’s archives, emceeing dinners and being honored herself repeatedly over the years. For a while there, her boldfaced name could be found in the Tribune’s Inc. gossip column on a regular basis.

I don’t know if Fred Hubbard is still alive. He may be. Death certificates in Cook County aren’t public record, but I can’t find an obituary for him anywhere.

Ironically perhaps, before leaving her work as a defense attorney, Arnette Hubbard was part of 3rd Ward Ald. Tyrone Kenner’s defense team in 1983. Kenner was convicted on 22 counts of mail fraud, extortion, conspiracy and obstruction of justice for taking about $20,000 in pay-offs.

I’ve spent a lot of time now with Fred Hubbard’s story rolling around in my head. What to think of him? Vernon Jarrett’s position is fair and understandable. Hubbard’s betrayal of public trust was monstrous.

Yet my first inclination, like many of Fred Hubbard’s constituents, is to feel sorry for him. Gambling is an addiction. Hubbard was smart, tough and hardworking enough to serve five years as a paratrooper, finish his GED and then get a bachelor’s degree from the University of Chicago. He clearly cared about people, choosing to work with those who needed help, like young men caught up in street gangs—when he could have easily gone into a much more profitable line of work. Gambling was an Achilles heel that destroyed him—but perhaps not all by itself.

Remember Hubbard was cheating on his wife, with whom he had a young child, both before and after he disappeared. Gambling doesn’t force you to betray the most important people in your life that way. It doesn’t even matter, in that sense, whether the charge of propositioning a 13-year-old in 1986 was true.

I still feel sorry for Hubbard. He is a tragic figure, as now long-time U.S. Rep. Bobby Rush observed while he served a stint as 2nd Ward alderman. But Hubbard is too complicated a tragic figure for unfettered sympathy. I can feel sorry for Fred Hubbard while forgiving people who can’t forgive him.

For much of Fred Hubbard’s disappearance from May 1971 to August 1972, most people figured he was dead.

But, of course, he wasn’t. Let’s get back to 1972.

***Why does the list of convicted Chicago aldermen start in 1973?

Does anyone think that not one single crooked Chicago alderman got caught red-handed and convicted until 1973? What a rhetorical question. I have no idea why Chicago newspapers always begin the list of convicted aldermen that year, because it’s 101 years late.

I’m not a historian, and I don’t have time to do a complete survey of convicted alderman over the course of the entire history of the city. But it was fairly quick work to find the first report of a convicted alderman in the Chicago Tribune archives, on January 20, 1872. So far as I can tell, the guy who should be getting this honor is Alderman Herman O. Glade.

Behold the fabulous 19th century headline style:

Ald. Herman O. Glade (11th), a liquor dealer, was convicted of bribery after a five-day trial. Charles H. Reed, Esq. opened for the state. The language is astonishing, so I’ll quote:

“He [Reed] recapitulated the nature of the charge made in the case, and claimed that he would show the delivery to Glade of the check of $150, by William Reinhardt, with the agreement that he, Glade, was, as an Alderman, to secure the removal of the hay stand from Randolph street, Reinhardt and others seeking its removal on the ground that it was an encumbrance to their property. He designated the crime as one of great infamy, and dangerous to society, because the betrayal of the public trust involves the whole community.”

William Reinhardt operated a butcher shop at 158-160 Randolph, which at that time was between Union and Halsted. Reinhardt testified there had been a hay market in the middle of Randolph between Desplaines and Halsted, for several years. Literally a hay market. Loads of hay were brought there by wagons, dumped into a stand, and then sold by hay dealers.

Reinhardt the butcher didn’t specifically say that he asked Ald. Glade to get rid of the hay market, but he described Ald. Glade coming into his butcher shop and asking if he’d collected money to pay for “expenses” to remove it. Reinhardt said he wrote Glade a check. He identified his signature on the back of the returned canceled check, which had been cashed and deposited into the account of Glade’s liquor business.

“Mr. Sidney Smith closed the case for the people. He remarked upon the length of time which had been occupied in the trial, accounting for it by the statement that it has become necessary to preserve the existence of the nation from an enemy more insidious than rebellion or invasion, and this is the first experiment to see if that enemy, modern official corruption, can be put an end to.”

God I would love to have seen that closing.

The jury took an hour and 15 minutes to return the verdict.

By the way, some things never change, but some things do:

After the trial, reporters tried to get a comment from the convicted alderman—that night, in the County Jail.

“When asked if he had a statement to make,” wrote the Tribune reporter, “he replied, ‘You make a statement to me: the newspapers know more about this thing than I do.’”

I think that was 1872-speak for “No comment.”

The Tribune reporter added that “Glade is not overburdened with intelligence”.

A reporter for the Chicago Times was even less successful, per the Tribune:

“A Times reporter, who represented that he was employed by the Post, essayed to converse with Glade last evening, but his visit was not at all satisfactory. He knew that if he acknowledged that he belonged to the Times, he could obtain no information, and the subterfuge was not as successful as he anticipated.”

The first alderman convicted of a crime in the 20th century was Ald. J.J. Brennan (18th), convicted in 1903 along with a couple of associates of paying two reporters to pose as two specific voters in a recent election for judges, and cast their votes. The two reporters testified that Ald. Brennan came inside the voting booth with them and marked the ballots.

The Tribune reporter on this case also went in search of comment later that evening. Ald. Brennan had not been sent to prison yet. He didn’t actually provide a comment, but he did give this wonderful description:

“Ald. John Brennan łatę last evening sat at the desk behind a railing just inside of the door of his saloon at 114 West Madison street and read the newspapers,” the Trib reporter recounted. “The customers who drifted in during the evening were served by the proprietor himself, and in between drinks the alderman went back to his papers.”

Who says the Front Page days were the 1930s?

August 23, 1972

Chicago Today: “You got me…It’s all gone,” Hubbard says

“The 15-month search for former Ald. Fred D. Hubbard ended without fanfare at a poker table in Gardena, Calif. when he looked up at two Federal Bureau of Investigation agents and said quietly:

“‘You got me. I’m Hubbard. It’s all gone.’”

Per Today, “Including the $50 he had just won at the poker table,” Hubbard’s “assets came to $151.25.” That’s $1,020 in 2022 money, compared to the $110,592 (~$750,000/2022) Hubbard allegedly stole from the federally-funded program he ran, the Chicago Plan, tasked with placing minorities in union construction jobs.

The government expected the Chicago Plan to find employment for 4,000 people in its first year. The program actually helped less than one hundred, if that.

The FBI staked out all six Gardena area gambling casinos after getting a tip that Hubbard would be found in one.

“Agent William J. Pettit was sitting in the Horseshoe Club yesterday afternoon when Hubbard walked in. ‘He surprised me because he is thinner than he looks in his pictures,’ Pettit recounted. ‘He was also wearing a mustache. But two things made me sure it was Hubbard. First, he walked like a cowboy [a rolling gait that was one of Hubbard’s characteristics], and second, his ears were flat on top, an unusual shape.”

Hubbard, dressed in a yellow shirt and brown jeans, had signed up for one of the $3 to $5 ($20-$33 in 2022) tables. Agent Pettit said that was another sign that Hubbard was truly broke.

Hubbard chain-smoked Marlboros during his initial interview with authorities. He refused to make a statement or waive extradition before using his phone call to contact his wife, attorney Arnette Hubbard, now said to be on her way to LA with her law partner Sam Adam.

Hubbard asked for milk for his burning stomach. Later reports will mention that he has ulcers.

August 23, 1972

by David Young

The other papers have dropped the new development in the police Hit Squad case, oddly enough—even the Defender. But the Trib’s David Young isn’t done with it.

“Warfare over narcotics traffic between established dealers and the Black P Stone Nation, not a police hit squad, was responsible for the deaths of black men on the South and West Sides and in Gary, according to suspended Police Sgt. Stanley B. Robinson,” Young opens.

Young also reveals that Robinson says he disappeared on June 26 because somebody tried to kill him that day.

Robinson says “the murders were the result of attempts by the Black P Stone Nation to muscle in on narcotics traffic on the West Side and Gary. The Nation traditionally has operated on the South Side,” Young writes. The Black P Nation murdered all six Black West Side men, according to Robinson. Two other later killings were cases of mistaken identity, he says. Plus, Robinson says the murders of three Nation members in a South Side apartment on July 2, and another the next day, were also part of the drug war.

Robinson, a former narcotics and gang investigator, claims he knew all about it for years. “I found out who the big people on the West Side were. They were legitimate businessmen.”

Per Robinson, the Chicago syndicate has nothing to do with any of it.

If you’re a regular THIS CRAZY DAY reader, you’ll probably want to follow Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today too.

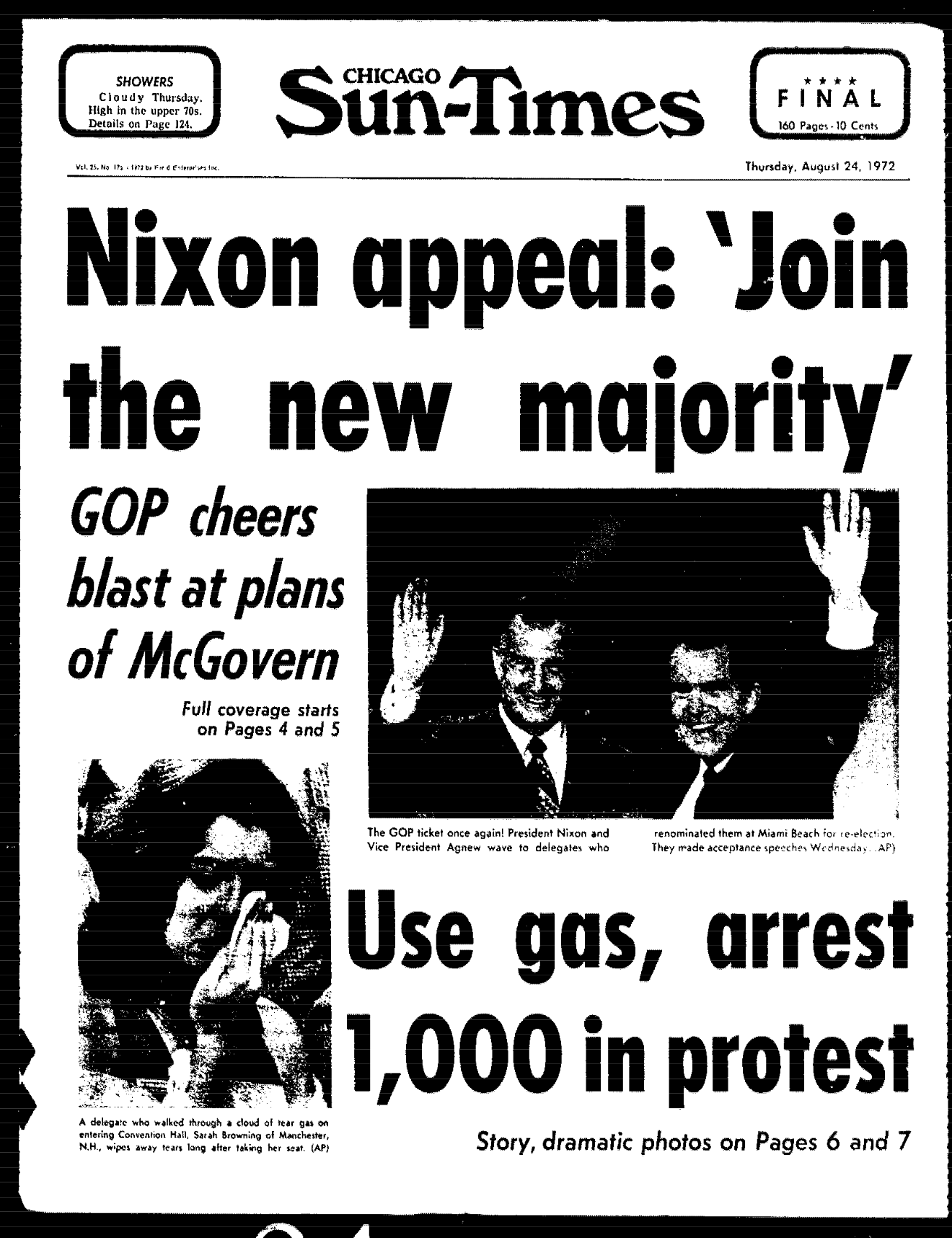

August 24, 1972: Republican National Convention

Oh yeah, things got real at the Republican National Convention!

The GOP also met in Miami—but everybody assumed it would be a complete snooze. Not so! I refer to the bottom half of this front page, not the top. The Sun-Times has the hierarchy of interesting stories precisely reversed.

And so does Chicago Today.

Unfortunately we don’t have time today to cover much of the convention this week—Fred Hubbard has sucked up all the TCD1972 oxygen. The Sun-Times’ Tom Fitzpatrick covers the “Zippies” battling Nazis in Flamingo Park, for instance. I’ll be doing future separate posts on both national conventions, where we’ll get to all these fun details.

For today, we’ll focus on the riots. Here’s the AP account in the Sun-Times:

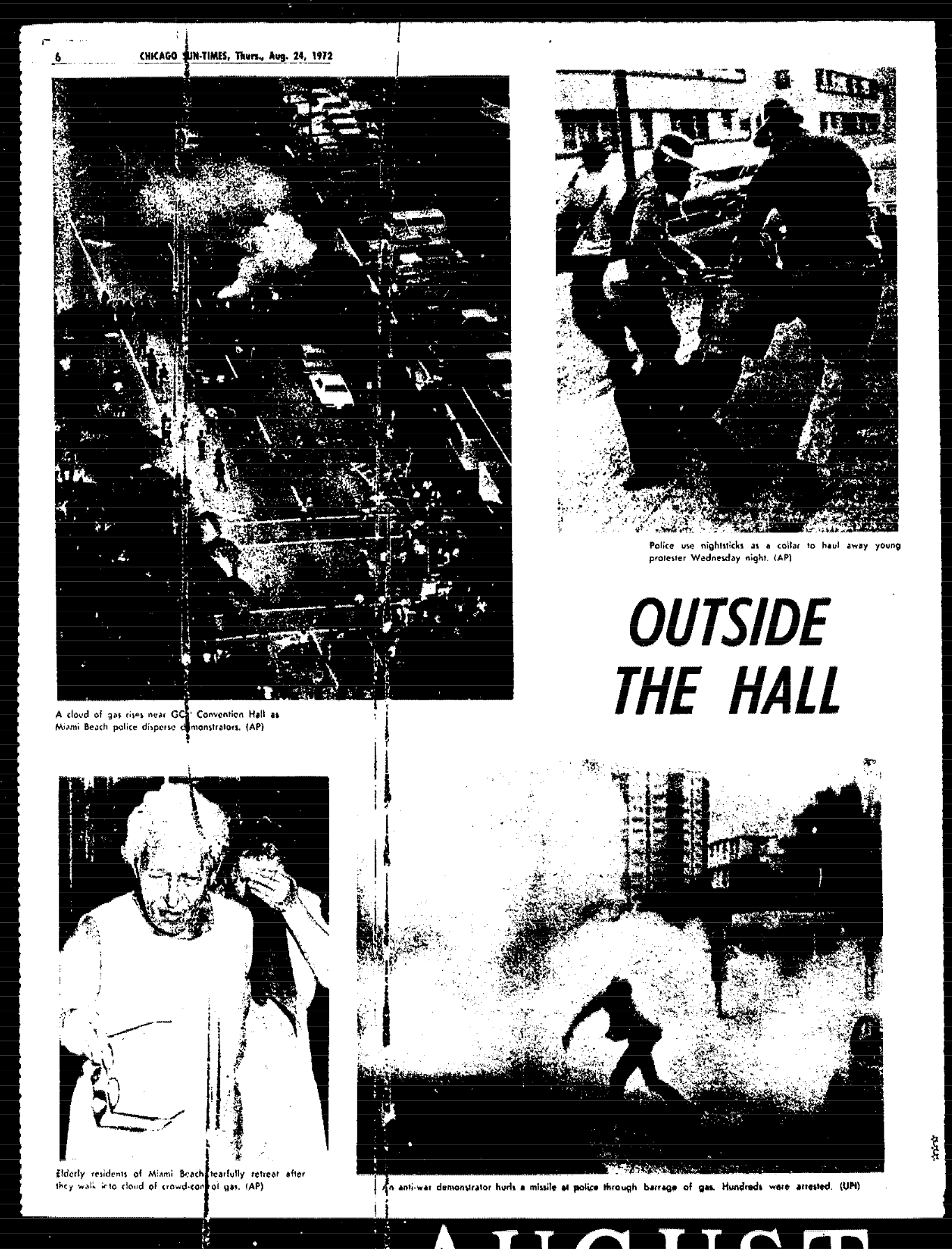

“More than 1,000 protesters bent on disrupting the Republican National Convention swarmed through the city Wednesday night, blocking streets, damaging autos and buses, setting fires, and smashing windows.

“They were met by massed forces and flying squads of police who cut them off at almost every turn and arrested hundreds who refused to disperse or failed to be fleet enough afoot.”

Police tentatively estimate they arrested 805, while hundreds escaped.

“A crowd-control gas known as CS swirled through the hot, humid air around Convention Hall as President Nixon and Vice President Spiro T. Agnew arrived without incident by helicopter to accept their nomination.”

Are you wondering why you only ever hear about the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago? Me too.

The delegates arrived by car, bus, and foot, not helicopter, so many were not as lucky as Nixon and Agnew.

The gas even “wafted into the hall’s lobby, and at least 40 persons were treated at the convention’s first aid center for the effects of the gas.” About 11 people were injured in the area immediately around the convention hall.

“For hours…demonstrators blocked traffic, deflated and slashed tires, sprayed paint on delegates’ cars—and on some delegates themselves, ripped wires off bus motors and distributor caps out of cars, smashed windows, and hurled garbage cans and rocks at delegates’ cars.”

“Protest leaders earlier in the day had urged the demonstrators to try to block main entrances to the hall and key intersections but said the confrontation should be a nonviolent gesture of contempt for the Nixon administration.”

That didn’t work out.

Several state delegations traveled to the convention by bus, and their buses were stopped by the crowd.

“The South Carolina delegates had a bad trip,” reports the AP, perhaps unironically. “Their bus was stalled in traffic about six blocks from the hall when demonstrators swarmed around it, slashing the tires with knives and cutting the radiator hose. The overheated engine soon died and the delegates and alternates had to walk the rest of the way through the hooting, jeering crowd.”

Chicago Today’s Jack Mabley also tells the story of the South Carolina bus. We’re not as familiar with Mabley as we are, for instance, with Mike Royko, who gets his own separate section. Mabley is frankly just not as interesting, though we can thank him for giving us Mike Royko—remember, Royko replaced Mabley at the Daily News when Mabley left for Chicago’s American, which became Chicago Today.

FYI, you might assume Mabley is a conservative Republican himself, just because he’s clearly middle-aged—or as some would say in 2022, he looks like a cis white heterosexual middle-aged man. But in 1972, going by his columns, Mabley would be considered liberal. His views track Royko pretty closely, though Mabley is more old-fashioned, shall we say. Mabley probably votes Democrat, but he’s just old enough in 1972 that he’s more leery (though quite polite) about women’s liberation.

Today, Mabley hits it out of the ballpark.

“The mob trapped the South Carolina bus when it stopped on Collins Avenue for a traffic light at 23d Street, four blocks east of the convention hall,” Mabley opens.

“Two of the hoodlums opened the motor cover in the rear and pulled the distributor wires. The others—maybe 30 or 40—ringed the bus, screaming insults and obscenities, shaking their fists, shouting ‘Murderers!’ The front of the bus listed to the right when the tire was slashed.”

Mabley describes the mob smashing open the bus door and pouring through, grabbing convention badges off delegates who sit petrified in their seats, spray-painting the bus windshield, and screaming.

“A young black man could take no more,” Mabley writes. “Alone, he pushed his way thru the hoodlums and into the bus. He yelled, ‘Stop it! Take your hands off these women! What right do you have to do this?’

“He was wearing a tee shirt and a funny Smokey Bear hat. He was tall and willowy but not especially muscular. He pulled the hoodlums from the bus. ‘All right, you’ll have to get off and walk,’ he told the South Carolinians, who seemed paralyzed.”

Per Mabley, two Miami Beach cops just stood and watched as the young man “led the incongruous band” toward the convention hall, shouting, “Come this way!”

“The mob saw they had no police protection, and raced after them,” Mabley continues. “‘They’re delegates! They’re delegates!’ They literally encircled the petrified band of delegates like jackals, darting in to hit and tear, cursing. I pushed thru to a woman in a long dress. ‘Where are you from?’ I asked. She turned to answer and an empty Pepsi can hit her on the head.”

Then, the young man leading the delegates noticed an “especially abusive” teenager. He “left the head of the column, went to the kid, literally picked him up by two hands around the neck, shook him like a rag doll, and tossed him half conscious onto the parkway. The black man stared down the kid’s gutless friends, and went back to the head of the column.”

Now I’m thinking Brad Pitt in “Once Upon A Time…In Hollywood,” at the Manson ranch.

A squad of cops finally arrived and chased away the rioters. The young man—Robert Moore, 26—watched the delegates finish their walk to the convention hall. Moore waxes cars for a living.

“Why did you do that?” Mabley asked Moore.

“They had no right,” Moore told him. “They had no right.”

Mabley goes on to cover the convention. Later that night, a South Carolina delegation member stands up on the convention floor and announces that they had to fight their way through “McGovern people.”

“They had recovered their courage behind the barbed wire and lines of police,” Mabley writes. “The gesture was ungracious. They were saved by a McGovern person. Not one said a word of thanks.”

August 24, 1972

Chicago Tribune

By Vernon Jarrett

“MIAMI BEACH, Aug. 23—Black delegates may not have managed to swing the Republican National Convention around to a liberal posture so far, but they will go down in the records as having thrown the swingingest convention party ever,” reports Tribune reporter and columnist Vernon Jarrett.

“‘This party makes Clement Stone’s luau look like a country picnic,’ said one white delegate who gained entrance to this invitational affair.”

“A majority of the 56 black delegates, 84 alternates and more than 100 black convention observers toasted each other and President Nixon until near daybreak today on two plush houseboats moored on the canal opposite the Fountainebleu Hotel.”

Who else was there? Sammy Davis Jr., of course….

…William F. Buckley…

…and three Cabinet members—Attorney General Richard Kleindienst, and the Secretaries of Commerce and of Labor. Plus a presidential advisor who would soon become the 13th and later 21st Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld.

Jarrett assures us that “only top brand name beverages” were “served at four bars and snack tables.” Guests waited for Sammy Davis Jr. and Vice President Spiro Agnew from midnight to 4 a.m.

Sammy was supposed to arrive by yacht but showed up via chauffeured limo, apparently just before dawn. Oh yeah. I can picture that.

No Spiro. Who needs him when you’ve got Sammy?

August 24, 1972

by Robert McClory

“Fred Hubbard’s arrest in California was triggered by a chance meeting with a former Southside campaign worker, who greeted the former 2d Ward alderman on a street in downtown Los Angeles several days ago, an informed source told the Daily Defender Wednesday,” writes the Defender’s Robert McClory. “Hubbard reportedly asked the unnamed acquaintance to loan him $50, and the man reported the incident to FBI officials upon his return to Chicago.”

$50 seems to be the magic number that Fred Hubbard hits people up for. That’s actually quite a lot of money—in 2022, it’s $337.50. Accounts of Hubbard after he gets out of jail mention him asking acquaintances for $50 too.

Rumors that Hubbard was fingered by Hit Squad suspect Sgt. Stanley Robinson appear incorrect, since the FBI was trailing Hubbard long before Robinson was apprehended Monday.

Sam Adam, law partner of Hubbard’s wife Arnette and now Hubbard’s defense attorney, says Hubbard will waive extradition.

“We plan to prove that he’s innocent,” Adam told McClory. “He’s going to prove all of the things said about him are false. He wants to go back home and prove his innocence.”

Chicago Tribune

by Peter Negronida

Negronida addresses the main theory of Fred Hubbard’s disappearance that dominated rumors for the past year:

“There had been speculation that Hubbard, who received $25,000 a year [from the Chicago Plan]…had been murdered in connection with the alleged embezzlement.

“‘I was surprised to learn that Hubbard was captured—I thought he was dead,’ said United States Atty. James R. Thompson, whose office has an indictment pending against Hubbard.”

Everyone Negronida talked to was surprised that Hubbard wasn’t dead, including the Rev. C.T. Vivian, whose Coalition for United Community Action’s picketing of construction sites helped create the Chicago Plan.

“I am thankful Fred Hubbard is alive,” said Vivian. “He has endured too much for his life to be taken lightly….Anyone, especially a black man, who has fought so hard to become a full person, deserves our serious attention and another chance.”

August 24, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender

Not everybody is a fan of “Super Fly.”

August 25, 1972

August 25, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times

The fear of killer bees begins, setting the stage for so many SNL sketches to come.

Have you read Chapter 2 of “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” yet? Follow Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, as he walks to work in 2003, from the IC station at Michigan & Randolph to the IBM Building. Meet everybody in Steve’s office, including his slimy boss, and find out what’s up with those conference room windows.

August 25, 1972

All four major dailies cover the tragic story of Rodney Harris. Unfortunately the Defender is unavailable on microfilm or its digital archive for this date, so we don’t know how/whether the Defender covered Rodney today.

by Roger Simon

“The naked body of a 14-year-old Chicago youth was found stuffed into a canvas sack and dumped in a garbage container Thursday near 1921 Harrison in Evanston,” writes Roger Simon.

The victim is Rodney Harris, missing from his home at 7930 S. Crandon since Wednesday when he didn’t come home. Rodney’s mother, Mrs. Mae Ella Harris, called Chicago police the next morning—then she called Evanston police, after reading initial accounts of an unidentified body found there.

Rodney, one of five siblings, graduated from Horace Mann Elementary and was set to attend Chicago Vocational High School.

Police say Rodney was strangled, then stuffed in a khaki canvas duffel bag and dumped in Evanston overnight.

The building janitor found Rodney’s body in the dumpster, located in a parking lot east of the building, “in plain view of many apartment windows”.

Chicago Tribune

The Tribune’s account includes one extra clue: “The boy was last seen at 6:30 p.m. Wednesday by a neighborhood friend near his home. His mother said he had left home at 12:30 p.m. that day, telling her he was going to play ball.”

The afternoon papers take up the story.

“‘He was a good boy,’ said the aunt of a slain South Side boy. ‘And he was never in any trouble and didn’t have an enemy to his name.’

“‘Miss Stella Harris of 9055 S. Euclid Av. said that her nephew, Rodney Harris, of 7930 S. Crandon Av., was never a gang member and had never stayed away from home.”

“He left his house to go play some baseball at the Mann School around 12:30 p.m.,” Stella Harris told Today. “There’s just no reason why he should have disappeared after that.”

Evanston police picked up Rodney’s mother, Mrs. Mae Ella Harris, and drove her to identify Rodney at the Cook County Morgue.

Rodney was a good student whose favorite subject was history. “Most of his spare time was taken up being a paper boy and following the Chicago White Sox.”

Daily News

by Phil Blake

“Evanston detectives have retraced the steps of 14-year-old Rodney Harris to less than a block and several minutes from supper in his South Side home,” the News’ Phil Blake reports.

Rodney was walking toward his house when a neighbor saw him at 6:30 p.m.

It hardly seems Rodney’s story could become more tragic, but somehow, this detail does just that.

“Fifteen hours after he was last seen, the boy’s naked body was found stuffed in an Army-type duffel bag in an Evanston trash container.”

“The investigation now centers on the 15 hours between then and when the boy’s body was found behind 1921 Harrison St. in Evanston.

Mrs. Harris says Rodney probably only had some change in his pockets. His clothes haven’t been found.

“Police said the boy had not been in trouble and were baffled about why anybody would kill him.”

August 25, 1972

Chicago Today

by Jeff Lyon

“Fred Hubbard’s defense is likely to be that he discovered Chicago Plan funds gone, then panicked and fled in May, 1971, according to his attorneys,” writes Today’s Jeff Lyon.

“‘It is a very good possibility that we will argue the Chicago Plan money was gone before Fred ever disappeared,’ said attorney Sam Adam last night. ‘We would presume he was unaware of it and when he found out about the loss he just panicked.’”

Hubbard’s wife Arnette, Adam’s partner, will also represent him. “Thus, court observers will soon see the unusual instance of a lady lawyer defending her husband in a criminal case.’”

A very 1972 turn of phrase, but essentially true.

Another Arnette Hubbard law partner, Edward Genson, is expected to argue for lowering Hubbard’s $50,000 bond—but they are “not optimistic” on that.

“Adam described Hubbard this way: ‘He is in good spirits. He is relieved and wants to come back to clear his name. When you run, really you want to get caught. He is one tired man.’”