Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today: Close Encounters of the Hanrahan Kind

October 23-29, 1972

To access all site contents, click HERE.

Besides Mike’s close encounter with Ed Hanrahan on October 26, read on for Mike’s take on the death of Jackie Robinson, one of Mike’s most touching columns, on October 25.

Why do we run this separate item, Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today? Because Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the serialized novel central to this Substack, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” lived in a Daily News household. The Bertoluccis subscribed to the Daily News, and back then everybody read the paper, even kids. And if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko. Get your Royko fix on Twitter too: @RoselandChi1972.

October 23, 1972

CPS has announced nonresident tuition for “Chicago’s famous schools,” as Mike puts it. In 2022 money, tuition is $6,412.50 for grammar school and $10,125 for high school.

For a little more, Mike notes you could send your kid to Mundelein College. The great thing about sending your kids to Chicago Public Schools, “besides…exposing the student to constant turmoil, strikes, and making him more worldly,” says Mike, is the great innovation going on at CPS.

Mike’s example: Orr School, 1040 N. Keeler, which includes both grade school and high school in one building.

As the 1972 school year began, it turned out there were too many students in one sixth-grade class.

“A student, Maria Aguirra, tells what was done to relieve the overcrowding in the sixth-grade room,” writes Mike.

“‘A day or two after the semester began, a teacher came into our room, and picked out four of us. They were all girls—me, Victoria, Sophie and Evelyn….She told us that we would have to go to another class, so we all went.’”

It’s a fifth grade class, where the girls were set to doing fifth grade work. Two girls have since transferred to other schools in order to get back into sixth grade.

“What happens to a student who passes the fifth grade, but has to take it over again?” asks Mike. “Maria says the teacher explained that to her.

“‘She said I shouldn’t worry, that I’ll go to the seventh grade next year. But I don’t know if I’ll be able to do the work in the seventh grade if I don’t learn the sixth-grade work.’”

Maria’s mother doesn’t speak English, and doesn’t know what’s going on at school. Maria’s remaining sixth classmate stuck in the fifth grade class is Sophia Sroczynski of 852 N. Kedvale. Mike or his leg creature talked to Sophia’s Mom, who emigrated from Poland and also doesn’t know what’s going on at school.

“The school never called me or anything,” says Mrs. Sroczynski.

“A source within the Orr school says: ‘I’ve seen some stupid things done in this system, but this tops any of them.’”

With this kind of education, Mike concludes, your kid “could someday qualify as a school administrator.”

October 24, 1972

“When the toll roads were repaved last summer, thousands of traffic barricades were rented at a price several times higher than it would have cost the state to buy them,” Mike tells us today.

“And the rental cost greatly exceeded the amount other highway agencies say is the going fair price.”

Who got that plum contract? Tom Bowler, “a onetime South Side tuck-pointer, who is now chauffeured about the city by Chicago cops, and jets politicians to their political conventions in his private plane.”

Bowler owns Brighton Construction Co., which together with Krug Excavating gets a big chunk of the Chicago public works projects through those companies and the many, many related smaller companies they control.

“A Chicago alderman—Michael Bilandic, of the Mayor’s 11th Ward—is the registered agent for all of them,” Mike reports. “Bowler and Krug got a major share of last summer’s toll road repaving work in the Chicago area.”

Wow! That’s some clout. Ald. Bilandic will succeed Mayor Daley, albeit briefly, after Daley’s death.

For the toll roads, Brighton’s Western Traffic Control Co. got $412,000 ($2.7 million in 2022 money) to provide the barriers, cones and traffic markings, plus a 24-hour patrol to keep an eye on them, for 13 weeks over 24 miles of toll road.

Mike’s math finds buying all the equipment outright would add up to $105,000, leaving $300,000 ($2 million 2022) for labor and profit. Though he notes the company already owned all the equipment.

Mike mentions that he’s written about Tom Bowler and Brighton Construction before:

“I once looked at $200 million in city public works projects covering four years. Bowler’s company, by itself or in joint bids with others, had been awarded almost $50 million contracts.”

That was Mike’s April 4 column, in which he noticed that Brighton’s rehab of the Michigan Avenue Bridge (later renamed the DuSable Bridge) was running four months behind schedule. Brighton had convinced the city to raise the bridge rehab fee by $500,000 in exchange for completing the job one year early, on Dec. 1, 1971. But with a $1500 daily penalty for every day past that date. In April, Brighton already owed $135,000—but the city wasn’t collecting.

Back to today’s Brighton contract:

“The remarkable thing about it is that it’s only a minor part of a highway project,” writes Mike. “It’s a drop in the bucket compared to the paving work, which runs into the millions.

“And the toll road work is, in turn, just a drop in the bucket compared to the volume of public jobs that Bowler and Krug get each year.

“It’s not surprising that Bowler can afford to buy his own jet and ride politicians around in it.

“I wonder what they talk about up there.”

If you dig Mike Royko, check out the news he’s writing about here!

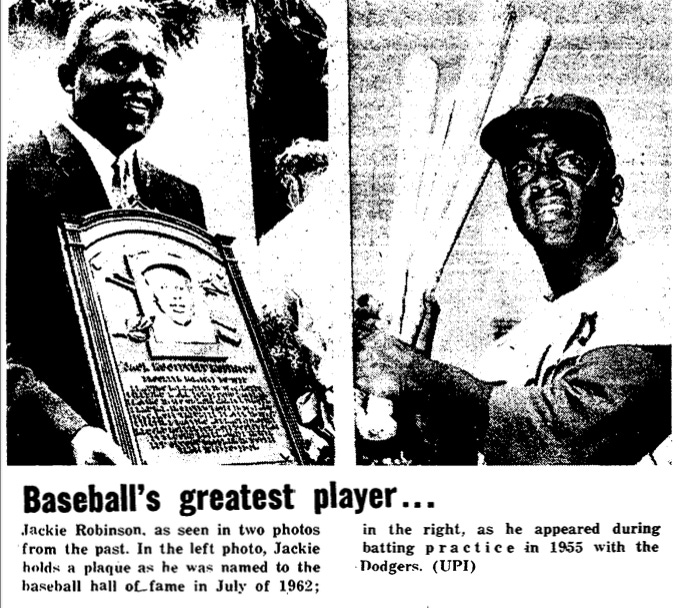

October 25, 1972: Jackie Robinson

October 24th was a sad day for Americans, not only baseball fans.

Jackie Robinson, just 53, the first Black major league baseball player, had been ailing for years. He’d suffered several mild heart attacks. Diabetes had taken his sight entirely from one eye, and most from the other.

Chicago Daily Defender sports editor Norman O. Unger began his Oct. 25 obituary for Jackie Robinson this way:

“‘There were so many ways he could beat you…’

“As news spread across the country that one of baseball’s most famous heroes had fallen victim to a sudden heart attack, that was the phrase most often repeated. ‘There were so many ways he could beat you…’”

“His most recent opponent was the same that he faced 27 years and one day before his death…Racism, in baseball.”

Unger is referring to Jackie Robinson’s final public appearance, ten days before his death, at the second game of the 1972 World Series in Cleveland. Robinson was honored that night for the 25th anniversary of his major league start. During his life, Robinson “frequently was mentioned in speculation as the man who might become the major leagues’ first black manager,” writes Robert Signer in the Daily News. But instead that night, as Chicago Today’s Bill Jauss recounts, Robinson stood before the “43,000 fans at the park and 80,000,000 TV viewers” and said, “I am extremely proud and pleased. But I will be more pleased the day I can look over at third base and see a black manager.”

Of course, Robinson would have been one of the leading major league players of all time even without breaking baseball’s color barrier by joining Branch Rickey’s Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. “He played on six pennant winners in his 10 years, had a lifetime batting average of .311. A gifted baserunner, he stole 197 bases,” writes Al Coxon in his Oct. 24 Daily News tribute. Robinson was elected to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.

“He was the kind of player that could, and often did, beat his opponent in four different ways…The long ball, a perfectly placed bunt, a stolen base at a vital point in the game, or his fielding,” writes Unger. “‘There were so many ways he could beat you…’”

Born in Cairo, Georgia as “Jack Roosevelt Robinson” in 1919, he soon moved with his family to Pasadena.

“I recall seeing Jackie for the first time when he was just a youngster,” writes the Sun-Times’ Edgar Munzol in the paper’s main first-day story. The paper identifies Munzol this way:

“Already an all-around star at Pasadena Junior College,” Munzol went on, “he played shortstop for the Pasadena Merchants in a spring game against the White Sox in 1937. His speed made the old eyes of manager Jimmie Dykes blink.”

Robinson “gained national notice in football, basketball and track” at UCLA, writes the News’ Signer, where he “won an All-America honorable mention in football, set a Pacific Coast Conference broad jump record and led the league in basketball scoring.”

“Jackie was named all around West Coast champion,” writes the Defender’s Unger, “and earned a commission in the U.S. Army as a morale officer overseas.”

After three years in the Army, Robinson played one season for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro National League. There he met Wendell Smith, then sports editor for the Pittsburgh Courier, the country’s most prominent Black newspaper after the Defender.

As the News’ Signer notes in his October 24 tribute, it was Wendell Smith who first told Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey about Jackie Robinson. In 1972, Wendell Smith is a Sun-Times columnist and WGN sportscaster. We first mentioned Smith’s connection with Jackie Robinson on January 15, when Smith was inducted as president of the Chicago Press Club. Sadly, Smith couldn’t attend the dinner because he’d just had surgery, and he will pass away soon himself in our 1972 timeline.

In Chicago, Smith worked first for Chicago’s American (which by 1972 is Chicago Today) before switching to TV. Smith went first to Ch. 2 (WBBM), and soon moved to WGN as sports anchor for the 5 PM and 10 PM broadcasts. He also wrote columns for the Defender before the Sun-Times.

Wendell Smith campaigned hard to break the color line in professional baseball, which is how he ended up recommending Jackie Robinson to Branch Rickey when he was looking to hire the first Black player in the major leagues.

For the Oct. 25 Sun-Times, Smith wrote about his initial contact with Jackie Robinson. Smith met Robinson in 1945 as he played shortstop for the Kansas City Monarchs. Then, Smith took Robinson and two other promising Black players to Boston for what was supposed to be a tryout for the Red Sox. On the train ride there, “Jackie said grimly, ‘I don’t know what’s going to come of this but if it means that the Negro player is a step closer to the major leagues then I’m all for it. I’ll do my best to help make this project a success.’”

The next day at Fenway Park, Jackie Robinson and the other two players joined “a group of sandlot and high school prospects” in a workout for Duffy Lewis, a former Red Sox star. “You’ll hear from us,” Duffy told them.

“On the way back to New York, Robinson said, ‘We probably won’t hear from him, but it may have put a crack in the dike,’” Smith recalls in the Sun-Times. “It did. I stopped off in Brooklyn while Robinson and the other two players returned to their respective teams in Negro baseball. Branch Rickey of the Dodgers expressed an interest immediately and from that point on had scouts tailing Robinson” and the other two.

“Jackie didn’t know it, but he was on his way to the majors then,” writes Smith. “Instead of Boston, however, he was to end up in Brooklyn.”

This week’s Robinson tributes all tell the famous story of how Branch Rickey hired Robinson. Here’s Bill Jauss from Chicago Today:

“Rickey outlined and acted out situations Robinson might have to face as the black trailblazer…. ‘What happens, Rickey asked, ‘if a man slides in…you make the tag…he swings at you…and calls you a ‘black xxxxxx!’ Robinson told Rickey that he would slug the baserunner. Robinson was quite stunned when Rickey told him he could not react that way.

“‘Mr. Rickey,’ he asked, ‘do you want a man who hasn’t the guts to fight back?’

“‘I want a man,’ Rickey replied, ‘who has the guts not to fight back.’

“….Robinson didn’t like it. He understood, however, when Rickey said, ‘If I get a firebrand who blows his top and comes up swinging after a collision at second base, it could set the whole cause back 20 years.’”

Next, Robinson “earned the right to play by batting .349 for [a Dodger farm team in] Montreal in 1946, the highest average in the International League,” writes the Daily News’ Al Coxon. The following year, Robinson hit .297 for the Dodgers and became the National League’s “Rookie of the Year” at age 29.

Coxon notes there was a “threatened strike by St. Louis players who didn’t want to play against the black man. The boycott never formed after Ford Frick, the National League president, threatened to suspend for life any who refused to play.”

“Dodgers players treated him as ‘one of the boys’ while enemy pitchers treated him with the respect he won from them with his bat alone,” writes the Defender’s Unger. “Most important from Robinson’s standpoint was the fact that his success ‘opened the door’ for other Negroes to play in the majors and in the minors.”

But according to an unsigned short piece in the Sun-Times, before Robinson began with the Dodgers, “There was a petition circulated by one of the Dodgers threatening to strike if Jackie were allowed to play.”

“[Dodger player] ‘Dixie Walker started a petition when we were still in spring camp,’ said coach Pete Reiser of the Cubs, then a Dodger star outfielder. ‘Several of the Southern boys were behind it. [Dodger shortstop] Pee Wee Reese and I were the last ones they came to for signatures. We both refused to sign. My attitude was that if he was capable of playing big league baseball he should be allowed to play….But I will say this for Dixie Walker. After the first month he went to Jackie and apologized, saying he had been wrong.’”

Wendell Smith covered Robinson for the Courier, and also traveled with him as a companion on the Dodger payroll at Branch Rickey’s request. So Smith was with Robinson continually for his 1946 season on the Dodgers’ farm team in Montreal, and for Robinson’s first year with the Dodgers in 1947. Smith then quickly wrote the first book on Robinson, “Jackie Robinson: My Own Story.”

According to all accounts, after Robinson’s second year with the Dodgers, when he batted .342 in 1949 as the National League’s leading hitter, Branch Rickey’s request to turn the other cheek was dropped.

“I’m a human being. I have a right to talk, haven’t I?” Robinson said at the time, a line quoted by several pieces.

The newspaper accounts all extol Robinson’s ability to quietly take the initial verbal abuse as the first Black player, noting that some Blacks, especially younger ones, still considered Robinson an Uncle Tom for it.

“The difficult period, of course, started in Montreal in 1946,” writes Munzol in the Sun-Times. “He couldn’t eat with the white players, he couldn’t go to a movie with them while they were training in Florida and he couldn’t stay at the same hotels.”

But the accounts also call Robinson “always controversial,” apparently referring to his Dodger career after he was done turning the other cheek. Most articles don’t bother to explain what that means, assuming 1972 readers can fill in those details themselves. “Some thought he was an agitator but he just wanted to get on base, steal second and win the game,” writes Al Coxon.

Wendell Smith does explain, describing scrapes Robinson went through in the Army, in Montreal, and later as an established player:

“He had a feud with manager Leo Durocher and never hesitated to shower an opposing pitcher he thought was throwing at him with a volley of obscenities,” writes Smith. “He slid into Roy Smalley of the Cubs here at Wrigley Field and they almost came to blows….He never backed down from a fight, never quit agitating for equality. He demanded respect, too. Those who tangled with him always admitted afterward that he was a man’s man, a person who would not compromise his convictions.”

“Jackie became a symbol of triumph for the black people. They stormed the ball parks whenever the Dodgers came to town,” writes the Sun-Times’ Munzol. “The Dodgers were the ‘home team’ even when they were on the road. And that included Chicago. The black fans outnumbered the Cubs followers at Wrigley Field and outcheered them.”

“He shattered the nerves of the pitchers as he danced around at first base taking long leads and finally breaking for second and another stolen base,” Munzol continues. “He would upset the entire infield and have the catcher so jittery the ball would be thrown all over the place. When Robby stole second he’d usually wind up on third base because the catcher would throw wild. So one day Frank Firsch, then managing the Cubs, snapped at his catcher, ‘When Jackie steals why the hell throw to second? Fire the ball to third and maybe we can keep him from going that far.’”

It’s interesting that in 1972, the papers have two different versions of how Jackie Robinson’s career ended in 1956. The Daily News writes it both ways all by itself.

One version, here from Robert Signer’s piece: “In 1956, the Dodger organization stunned the Brooklyn fans and the baseball world. Robinson, then 37, was traded to the archrival New York Giants. But he wouldn’t go. If he couldn’t play for Brooklyn, he wouldn’t play for anybody. He came up as a Dodger; he would quit as a Dodger. And he did.”

Version #2, also from the Daily News, this time by Al Coxon: “The end of his career was a typical Jackie Robinson finish. The Dodgers shifted their franchise to Los Angeles after the 1965 season and Robinson didn’t like it. Then 37, he decided to retire, a decision announced in Look magazine. The Dodgers traded him to the Giants, who offered him a two-year contract. ‘Robinson will play,’ said Dodger general manager Buzzy Bavasi, who now runs the San Diego Padres. ‘He’s got his money from Look now, so he’ll take the money from the Giants.’ If he ever was tempted to play for the Giants, Bavasi prevented it because Robinson had pride. His career was over.”

Accounts agree that Robinson then went to work as Vice President of the Chock Full O’Nuts restaurant chain. Signer: “His job was concerned mostly with expanding and guiding the chain’s minority programs.” Later, he founded the Freedom National Bank in Harlem, and his own insurance firm.

Meanwhile, Robinson also worked in the civil rights movement—and the Republican Party, which drew criticism and disbelief when Robinson backed Richard Nixon against John F. Kennedy in 1960. In 1968, however, Robinson campaigned for Hubert Humphrey.

Sadly, Robinson’s son Jackie Jr. became addicted to drugs, overcame addiction, but died in a 1971 car crash on his way home from his job at a drug rehabilitation program, according to all accounts in the dailies.

“Branch Rickey gave Jackie Robinson an opportunity in the spring of 1947. That was all the first black ballplayer in the major leagues needed to have handed to him,” wrote the Daily News in an editorial the day Robinson died.

“Author Roger Kahn, describing Robinson, said: ‘Like a few, very few athletes, Robinson did not merely play at center stage. He was center stage; and wherever he walked, centerstage moved with him,’” the News editorial concluded, quoting Kahn’s famous book “The Boys of Summer,” which had just been published earlier this year (1972), and was already so well known that the paper could simply allude to its title in the editorial’s last sentence: “And it might be added that Jackie Robinson was a man among those boys of summer.”

Jackie Robinson’s autobiography was just about to be published when he died, as the Daily News’ Al Coxon noted. “The title of Jackie Robinson’s autobiography that will be published next month is ‘I Never Had It Made,’ and he never did, not at the start, not in his Dodger hey-day nor in the trouble-filled years after he left baseball,” Coxon wrote.

Coxon quotes the ending of Robinson’s autobiography:

“I have always fought for what I believed in. I have had a great deal of support and I have tried to return that support with my best effort. However, there is one irrefutable fact of my life which has determined much of what happened to me.

“I was a black man in a white world. I never had it made.”

“He broke the ground for the scores of black men who now are the mainstays of every major league team, the winners of numerous top awards, the unquestioned superstars who draw the fans to the ballparks in records numbers,” wrote the News’ Robert Signer in a tribute that ran October 24 in the News’ regular “Insight” slot—top of page 5 with a jump to page 6. “It was not easy. There were times when it seemed that Jackie wouldn’t make it, not because he didn’t have the ability or the inner strength, but because he was fighting a nearly unbroken wall of racial prejudice that permeated the world he was trying to move into.”

The Defender’s Norman Unger quoted one of the Black players who quickly followed Robinson:

“Joe Black, former pitcher with the Dodgers near the end of the ‘Robinson era,’ is one of the many who knew the greatest player the game has known. Black said in an interview Tuesday, after learning of Robinson’s death, ‘I owe a lot to Jackie. I have a good job, a nice home and a lot of doors are open to me that could have been closed had Jackie failed. Sometimes when I look at the grass around my house, I say, ‘Thank God for Jackie Robinson.’”

Mike’s column on Jackie Robinson

Read the whole column in “Slats Grobnick and Other Friends”—really, please go read the whole column. This one opens with a classic Mike storytelling method, backing you into the story and communicating even more about the time period and people he describes with what he doesn't say. Recall that Mike grew up in a largely Polish neighborhood near Humboldt Park, living above his family’s Blue Sky Lounge at 2122 N. Milwaukee.

“All that Saturday, the wise men of the neighborhood, who sat in chairs on the sidewalks outside the tavern, had talked about what it would do to baseball,” Mike opens.

“I hung around and listened because baseball was about the most important thing in the world, and if anything was going to ruin it, I was worried.”

Mike didn’t understand most of what he heard, but it sounded terrible. “How could one man bring such ruin?”

Jackie Robinson was about to play at Wrigley Field for the first time, and Mike had to see it. So he and a friend started walking the five or six miles to the park. The park was packed. Mike and his friend just managed to get in and find a place to stand “behind the last row of grandstand seats.”

“I had never seen anything like it. Not just the size, although it was a new record, more than 47,000. But this was 25 years ago, and in 1947 few blacks were seen in the Loop, much less up on the white North Side at a Cub game.

“That day, they came by the thousands, pouring off the northbound L’s and out of their cars.

“They didn’t wear baseball-game clothes. They had on church clothes and funeral clothes—suits, white shirts, ties, gleaming shoes and straw hats. I’ve never seen so many straw hats.”

The crowds behaved, with little jostling from Black or white. “For most, it was probably the first they had been that close to each other in such great numbers,” writes Mike.

Mike remembers the “long, rolling applause” when Jackie Robinson came to bat, even though he hit a foul and then struck out. “When Robinson stepped into the batter’s box, it was if someone had flicked a switch. The place went silent.”

A tall, middle-aged Black man standing next to Mike clapped for Robinson’s foul ball, “beating his palms together so hard they must have hurt.”

Otherwise, Mike remembers two things: First, one of his heroes on the Cubs hit a grounder and ran to first, where Jackie Robinson was stationed, then obviously tried to hit Robinson with his spikes. Mike was shocked.

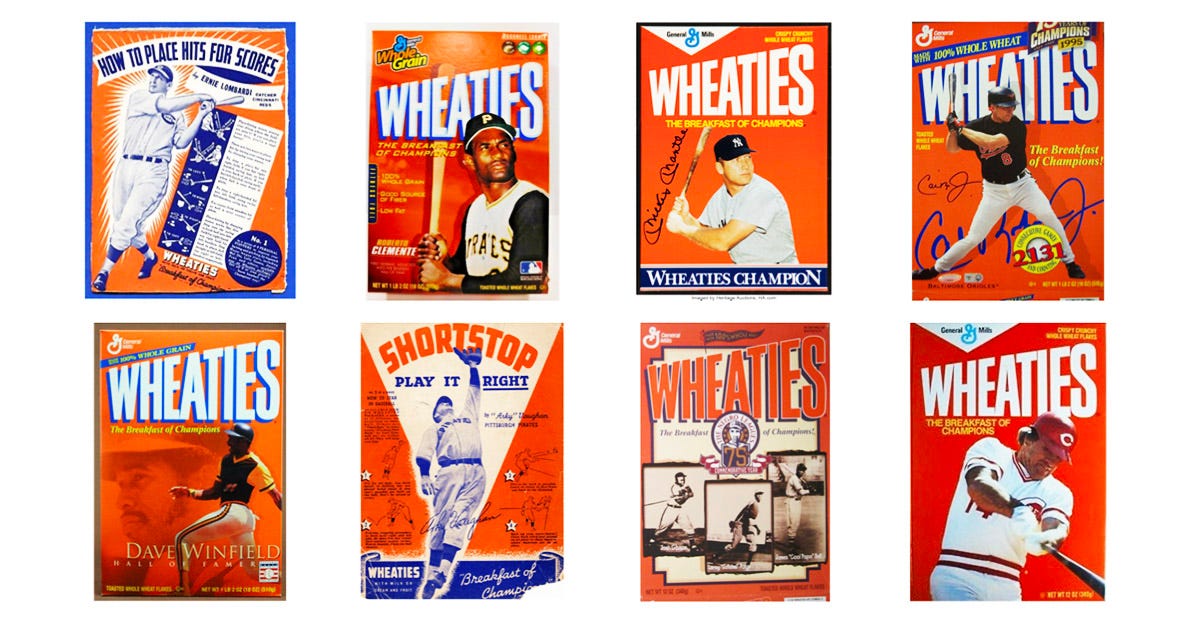

“I didn’t know that while the white fans were relatively polite, the Cubs and most other teams kept up a steady stream of racial abuse from the dugout. I thought all they did down there was talk about how good Wheaties are.”

Second, an amazing thing happened: Jackie Robinson hit another foul that flew up into the stands and landed between Mike and his friend—and Mike got it.

“Then I heard a voice say: ‘Would you consider selling that?’

“It was the black man who had applauded so fiercely.”

Mike of course doesn’t want to sell it, but the man offers $10—when men in Mike’s neighborhood considered $60/week good take home pay. That $10 would be $133 in 2022. Of course, Mike finally agrees.

“Since then, I’ve regretted a few times that I didn’t keep the ball,” Mike concludes. “Or that I hadn’t given it to him free. I didn’t know, then, how hard he probably had to work for that $10.

“But Tuesday I was glad I had sold it to him. And if that man is still around, and has that baseball, I’m sure he thinks it was worth every cent.”

October 26, 1972

“Ed” is Cook County State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan, “The county prosecutor who has to campaign for re-election at night because by day he is a defendant in the Black Panther conspiracy trial,” as a Sun-Times article recently described him.

Hanrahan is running against Republican Bernard Carey, a former FBI agent.

It’s a dynamite week for Ed Hanrahan, politically and legally.

Politically: Earlier this year, Mayor Daley dumped Hanrahan from the Democratic primary ticket after the Illinois Supreme Court refused to dismiss the conspiracy to obstruct justice charges against Hanrahan and 13 co-defendants, for allegedly tampering with evidence after the predawn 1969 state’s attorney police raid on a Black Panther apartment that killed Panthers Mark Clark and Fred Hampton.

But Hanrahan ran in the primary anyway, beating Daley’s hand-picked substitute. And now, if only because Mayor Daley doesn’t want a Republican state’s attorney digging into his business, Daley is exhorting the Machine stalwarts to get out the vote for a straight Democratic ticket. Every straight Democratic ballot is a vote for Hanrahan.

Over at THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 this week, we have an Ed Hanrahan Primer just before coverage of Tom Fitzpatrick’s Sun-Times column, in which Fitz witnesses Hanrahan’s triumphant reception and performance at Ald. Seymour Simon’s 40th ward precinct captain’s rally before the rapidly approaching November election.

Hanrahan tells the precinct captains he’s not spending a penny on newspaper advertising: “I’m keeping it and after Election Day I’m going to throw the biggest party for Democratic precinct captains that this town has ever seen. And all you’ll need to get in is a ticket from Seymour Simon showing that you carried your ward for the Democratic ticket.”

Legally:

See here for the full coverage of the over-the-top Hanramania coverage after the acquittal. All the papers review the 1969 raid, its aftermath, the 1,056-day trial, and the dramatic scene in the courtroom as Hanrahan and his 13 co-defendants went free.

Chicago Today’s Jeff Lyon covered Hanrahan’s hectic schedule that day and night, hopping from restaurant to restaurant eating, drinking, partying and campaigning. Hanrahan started with lunch at the legendary Dianna’s, 212 S. Halsted, where he took a picture with the even more legendary Petros…

…and later stopping at other vanished classics of the 1972 Chicago restaurant scene such as Nielsen’s, 7330 W. North Ave. in Elmwood Park…

…and Zum Deutschen Eck, 2924 N. Southport, which closed in 2000 after a 50-year run. It’s a parking lot in 2022.

This is where Mike Royko lay in wait for Ed Hanrahan.

“Hanrahan looked buoyant when he strode through the front door,” writes Mike, “a few seconds behind his advance bodyguards.”

Hanrahan is going fast, shaking hands as he goes. “Politicians sometimes grab a hand before they focus on the face of its owner,” writes Mike. “Thus it came that Hanrahan found himself pumping my paw.

“‘It’s me,’ I said, feeling that a warning was only fair.

“‘I know it’s you,’ he snarled, dropping my limb.

“He started to move on, then wheeled and jutted out his magnificent jaw.

“‘I want you to know,’ he said, his voice getting shrill, ‘that the rottenest column ever written about anyone, the rottenest column I’ve ever read, was the rotten column you wrote about Vince Garrity.’

“He put his nose an inch from mine. I hoped he wouldn’t sneeze.

“‘I just wanted to tell you that,’ he said.”

The strange thing, as Mike himself mentions, is that the September 25 Vince Garrity column was a perfectly nice remembrance of a colorful Chicago political character. See the Chicago History Rabbit Hole embedded in that column coverage for more. Thumbnail:

Vince Garrity figured out how to get on the radio, then figured out how to use his radio show to attain his greatest wish—political office, as a Metropolitan Sanitary District trustee. Vince was best known for popping up in pictures like a Chicago Zelig at big events, like John F. Kennedy’s wake and funeral. But Vince’s life had gone to shit a few years before he died in 1972, at age 52 or 53. Vince was always known to have a temper. Then he got arrested for beating his wife; she divorced him; he got arrested again, this time for drunk driving; and the Machine didn’t slate him for re-election in 1970.

Mike wrote about Vince four times, in 1964 and 1965, when he was still new to the column biz—those columns are also covered with Mike’s Sept. 25, 1972 Garrity tribute column. My hunch is Mike quietly dropped Vince from the line-up as he cultivated enough other sources to fill his space, and Vince’s life spiraled out of control. Mike’s memorial column for Vince recalls their hilarious first meeting and several other silly anecdotes. Diplomatically, Mike only mentions quickly that Garrity “dropped out of politics” due to his health “and an uncontrollable thirst.”

Mike says that column was a “fond remembrance of the little character,” and that’s a fair assessment. “We had become close friends during his last few troubled years. After the Machine discarded him and people like Hanrahan were too busy to see him, he had to have someone to talk to.”

After haranguing Mike, Hanrahan pushes on into a dining room where about 100 elderly people were gathered, honoring a precinct captain named Frank.

As Hanrahan approached the door, he asked his bodyguards, “What’s this about?” and learned Frank’s name. Then he swaggered inside and held forth at the microphone, praising Frank’s hard work—without people like Frank, people like FDR, Harry Truman and JFK might not have been elected. That kind of thing.

“Hanrahan put his hand on the precinct captain’s shoulder and smiled warmly at him.

“‘Frank,’ he said, as if he had known Frank for 30 years, instead of 3 minutes. ‘I see a man like Frank—take a look at him—and I see the picture of integrity, the picture of industry.’”

I see now why the Daily News ran this photo of precinct captain Frank Nimietz and Hanrahan at Zum Deutschen Eck, and right next to Mike’s column on page 3.

Bonus: Mike opens the column by noting that Zum Deutschen Eck owner Al Wirth told him that notorious Ald. Charlie Weber, “one of the Machine’s all-time rascals,” had been born upstairs in the restaurant’s building.

“Weber was a real crook,” Mike writes, “but he could get away with anything because somebody like Ed Hanrahan was always the state’s attorney.”

October 27, 1972

“If there’s one act in show business I can’t stand, it is the nightclub magician,” writes Mike.

“With their suave posturing, their frozen smiles, inane lines of patter, awful jokes, and overdone mannerisms, they make Liberace seem natural.”

And now, reading the front pages, “I get the feeling that I’m watching a nightclub magician. The act is almost four years old, and now we’re getting the final suspense treatment leading up to that last, big trick and the great burst of applause.

“For four years, it’s been one surprising feat after another.

“Look at that—he pulled a trip to China out of his sleeve. Ooooh, aaah. Take a bow, take another bow.…..Wait a minute, he’s reaching in. Wow! Some kind of an agreement with Russia. Ooooh, aaah.”

Now Mike refers to the headlines this week about peace in Vietnam.

“If you look at those peace terms, you’ll see that they are not so remarkable that they couldn’t have been obtained before. Fifteen thousand have died during the past four years, so every extra day it went on meant somebody’s life,” he notes.

But the magician “saves his best trick for the end, as we know he will all along. Or does anybody actually think that this is just the way things worked out; that after almost four years, now, only now, a few days before the election, could they finally be coming to an agreement.”

“For God’s sake, the damn treaty is right there in the hat,” Mike finishes. “Pull it out, sign it, fling up your arms in triumph, and get it over with. You’ve already sewn up your encore.”

Younger Readers: Mike means that everybody knows Nixon is about to trounce Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern. Sorry if that’s a spoiler!

October 28-29, 1972

As we here all know, weekends could be sad for a Daily News family because Mike Royko wasn’t in the Daily News’ single weekend edition. So we look for Mike elsewhere on weekends.

There was so much great and interesting writing after the death of Jackie Robinson, I’d like to share a few more excerpts.

Chicago Tribune

Oct. 29, 1972

“Jackie Robinson—like hero Joe Louis—came along just in time to keep hope alive in the breast of the black American. That fact alone, when placed in historical perspective, could ensure his immortality,” writes Tribune columnist Vernon Jarrett.

“Jackie was our black victory, our winner, our ‘living proof’ during a moment in post-World War II America, when the antiracist aims of the war had been forgotten by so many, and millions of blacks in the rural South and the overcrowded ghettoes of the North were tasting the bitter fruits of disillusionment.”

….“Black America needed a fresh symbol, a universal symbol, to keep a battered spirit alive.

“And then came Jackie.”

….. “When Jackie stole second base, it was us—all of us. When he scooped up those hot grounders it was us again—doing what we had been doing all our lives. And when he swung hard and missed for a strikeout, millions of hearts beat rapidly in the breasts of black people.

“But when he stroked that home run we rounded the bases with him. Jackie, baby, you were us.”

Chicago Daily News

October 28-29, 1972

by Betty Flynn

Our New York Correspondent

“New York—It was a joyful, musical final tribute to baseball great Jackie Robinson in the gothic towers of the Riverside Church.

“‘In this last dash, Jackie stole home,’ said the Rev. Jesse Jackson, leader of the Chicago-based Operation PUSH in the funeral eulogy Friday.

“‘He played a black chess game in which he was the black knight, checkmating King Bigotry and Queen Indifference.’”

“The massive church nave was filled with weeping mourners, more than 2,400—including well-known sports figures, politicians and the common people of the black neighborhoods that remembered Jackie as a fighter for their freedom.”

…. “He turned a stumbling block into a stepping stone,” Mr. Jackson said. “He had the capacity to wear glory with grace. Jackie’s powerful arms not only lifted bats but broke barriers, snapped the barbed wire of racial prejudice…..He was a rock in the water, creating concentric circles and new ripples of the possible.”

…. “Roberta Flack played and sang a traditional Negro spiritual, ‘I Told Jesus,’ at the end of the service.”

….“Outside, the funeral cortege of black limousines wound through the streets of the Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant black ghettoes before arriving for interment at the Cypress Hills Cemetery, near the site upon which Ebbets Fields, where Robinson made baseball history, was built.”

October 28, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender

Louis Martin, vice president, editorial director and weekly columnist for the Defender, writes that every time he saw Jackie Robinson, “I was reminded of another great American who had an interest in baseball but never made his mark in the game. Nevertheless his efforts may have helped to shake the gate which Jackie finally broke open in a blaze of glory. I am thinking of Paul Robeson.”

“Four or five years before Jackie played his first game for the Brooklyn Dodgers, I listened to the eloquence of Paul Robeson calling for an end to the color bar in a meeting of blacks with the late baseball commissioner Kenesaw ‘Mountain’ Landis. We were all members of the National Newspaper Publishers Association and we had asked for the conference with the commissioner. Paul Robeson, who was among other things a distinguished athlete and former football All American from Rutgers, was chosen to make our case.

“Landis flatly denied that there was a color bar in major league baseball. We couldn’t believe our ears. His views were so ridiculous that, despite our anger, we could not help laughing. When our spokesman got through with him, we all knew why Paul Robeson had won a Phi Beta Kappa key in college and why as a lawyer and later as an actor and concert artist, he was a superstar.”

“Jackie’s life story, almost a legend by now, is too well known to warrant retelling here. Indeed he fought and won his way into American history. As with most heroic blacks, his life can be described as bittersweet.”

October 29, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times

by Jerome Holtzman

“Suddenly, this book is a memorial instead of another retelling of the Jackie Robinson story,” writes Holtzman.

This latest Jackie Robinson autobiography comes after many other versions of the great ball player’s life, writes Holtzman—first Wendell Smith, then Bill Roeder, “both of whom traveled with the old Brooklyn Dodgers,” plus Carl Rowan, and most recently Roger Kahn in “The Boys of Summer.”

“Now Al Duckett, a Chicago-based free-lancer armed with a tape recorder, takes his turn at bat.” Holtzman finds that Duckett “begins digging into fresh turf,” and the second half, when Jackie has retired from baseball, is just as interesting.

“On the field, Robinson was an instinctive player, seldom making mistakes and always sensing the correct play. Off the diamond, Robinson concedes his instincts sometimes betrayed him. He admits to major errors in supporting Richard Nixon against John Kennedy in 1960, in opposing Martin Luther King’s stand on the Vietnam War and in resigning from the NAACP.

“The most tragic and irreversible error was his neglect of his oldest son, Jackie Jr., a dropout who was hooked on drugs and died in 24 in an automobile accident. Said Robinson, who didn’t spare himself in discussing this failure:

“Unfortunately, much of the time I wasn’t available to him, particularly after my baseball career when I became deeply involved in the civil rights movement and politics and traveled constantly. Ironically, a lot of my time was taken up at meetings and sports events sponsored by organizations that were in the business of helping youngsters.”

“The Jackie Robinson Story, regardless of how often told, is nonetheless an inspirational story—for both black and white.”

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, plus the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. Sometimes you can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many iconic columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there’s riveting work covered here you will never read elsewhere.

If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career which includes a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

You managed to misspell Edgar Munzel's name right above the Sun-Times printing his name!