Chapter Three: Me and Steve and Gil

Part B - Columbo: Murder That's Black and White and Read All Over

Note: If you’re a new reader, start with CHAPTER ONE: A GOOD LIFE RUINED or even the ABOUT page—and see you back here soon. Note: If you’re a new reader, start with CHAPTER ONE: A GOOD LIFE RUINED or even the ABOUT page—and see you back here soon. To access all contents on the site, click on the rose icon in the upper left corner or HERE.

Part B - Columbo: Murder That’s Black and White and Read All Over

The 1960s and 70s are part of a historical period, only recently slammed shut in our 21st century faces, when nearly everyone read daily newspapers.

Statesmen and titans of industry read newspapers. So did the working class and poor. Men and women, all races, ethnicities and religions, everyone--everyone read newspapers. In Steve’s childhood world, plenty of kids even read newspapers. That was a normal thing, kids reading newspapers! Kids skipped the boring front page stories about the Vietnam war, of course, but they still looked at the paper, if only for the comics. Kids had to flip through the paper to find the comics, which were always somewhere in back. As they flipped pages, they’d see the pictures and the headlines go by, and they’d absorb a little bit of the newspaper world that way.

This Age of Newspapers came about thanks to the temporary convergence of three developments, it seems to me:

1.Printing presses and paper factories made newspapers cheap enough for the average person to buy every day.

2. The average person was finally educated enough to read.

3. The average person wanted to read the newspaper because there still wasn’t much else to do. This last one is just as important as #1 and #2. Admittedly this is my theory, though I suppose it came mostly from talking to Gil in the University of Chicago Regenstein Library microfilm room. I didn’t read it in a communications class in college or anything.

You have to understand: Despite the trappings of modern life like toasters and refrigerators, the mid 20th century was a very different time from the 21st, or whenever you may be reading this. No Biblical-level flood of cute animal videos and free porn poured forth from the internet, gushing out of desktop home computers, much less phones. No cell phones or desktop computers, period. Computers filled entire rooms and buildings, and were thus confined mainly to NASA and science fiction. That’s something you may know intellectually, but after wading through the weeds of 1972 newspapers, it really gets pounded home.

In 1971, when rumpled Los Angeles homicide detective Lt. Columbo visits a ritzy private detective company run by snobby murderer Robert Culp in Columbo’s first season episode Death Lends A Hand, an employee gives Columbo a tour of the state-of-the-art computer room.

We only see a slice of the computer room, but we’re meant to imagine it goes on and on. Towering fake computers line the walls, rattling and clicking away. The place sounds like a 19th century sweatshop turning out women’s shirtwaists.

“There are more electrical impulses in this room than in your brain,” grins Robert Culp’s employee.

“Hard to believe,” Columbo marvels, shaking his head of shaggy brown hair, mouth agape, waving his cigar in one hand.

That was the closest a 1971 police detective would ever get to computers, and watching Columbo was the closest nine-year-old Steve and most other TV viewers got to computers as well. (Note that in Barney Miller, which ran 1975-1982 focusing on the detectives of Manhattan’s 12th precinct, everyone from Harris to Dietrich and Wojo still use typewriters.)

More Columbo just up ahead, but first let’s finish considering what media existed to amuse people in 1972. We’ve established via Columbo that there were no computers in a regular person’s world. You couldn’t just sit in a chair and play games on your phone all day, or watch YouTube or TikTok videos.

Broadcast television existed—no cable or streaming of course—but what could you watch?

Even if you lived in a huge metropolitan area, the main dial on your TV had a paltry 12 numbers, from 2 to 13—and only some of the channels worked. There were three national TV “networks”—groups of local stations owned or affiliated with one company, showing the same programming at the same time: the Columbia Broadcasting Company (CBS), the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), and the American Broadcasting Company (ABC). In Chicago, CBS aired on Ch. 2, NBC on Ch. 5, and ABC on Ch. 7.

Aside from the three networks, a few more numbers on a TV dial might bring you independent, non-network local stations. In Chicago, Ch. 9 was WGN (World’s Greatest Newspaper, the slogan of its owner, the Chicago Tribune) and Ch 11 was WTTW (Window to the World), the city’s public TV station. Ch. 9 was independent by default—it had aligned itself mainly with the DuMont Network, which went out of business by 1956.

Every TV also had a UHF (Ultra High Frequency) dial. The UHF dial had a seemingly random group of higher numbers, and almost none of them worked. In Chicago, if your antenna reception was really good, you got a wavy picture on Ch. 32 and Ch. 44, and maybe 26. Don’t believe me? This is what a TV dial looked like.

This is the main dial on the 1956 Zenith black-and-white TV in the basement of Steve’s childhood best friend, Paul Siciliano. The Sicilianos were the only family on the block with a second TV. That cemented their status as neighborhood celebrities.

Steve often wondered what was on channels 3, 4, 6, 8,10, 12 and 13. In Chicago, those stations were nothing but static. Steve’s Nonna said you could lose your soul to the devil just watching the static on Channel 13, because of the unlucky number. Steve doubted it but he never let the dial linger there.

UHF reception was generally so awful you had to use yourself as a human antenna extension to watch a show on 32 or 44, planting one hand on the TV to keep the picture from dissolving into static. You had to be heavily motivated to watch a UHF channel.

Television, then, was quite limited. Children’s television, even more so. Saturday mornings, the networks ran mostly awful low-quality kid’s cartoons nonstop. Weekdays in Chicago, there were basically three kid shows—all on local Ch. 9, all produced in town at the WGN studio: early morning, Ray Rayner and Friends; noon, Bozo’s Circus; and after school, Garfield Goose.

To put mid-20th century children’s TV programming in more perspective, Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood started in 1968, Sesame Street in 1969—both too late for Steve, who had just started school. In 1972, they were starting to talk about reducing the commercials during children’s Saturday morning cartoons from something like 30 minutes of ads per half hour to just 25 minutes. OK, the numbers weren’t quite that high. I don’t remember the exact numbers, but they were still ridiculous.

You may be saying: What about Captain Kangaroo? Yes, Captain Kangaroo aired weekdays on Ch. 2 starting in 1955, but the Bertolucci’s tended to stick with Chicago’s Ch 9.

Otherwise, daytime TV in the ‘60s and ‘70s consisted almost entirely of soap operas, awful game shows, reruns of old sitcoms (mostly bad ones), and old movies chopped up into a thousand pieces for commercials. Oh, but not the kind of cool adult shows and movies that kids aren’t allowed to watch. Grown-ups back then authorized the government to make sure all TV shows were tame enough for the smallest child. Movies had more leeway, but if a movie had some kick to it at the theater, they cut out the good stuff before they put it on TV. The grown-ups did this to themselves, of their own free will.

What about books? They were often scarce in a working class neighborhood like Steve’s. The only thing you could always count on was a Bible, tucked away somewhere in nearly every house. When you were really hard up for reading material, you might actually flip through that Bible, if it had enough pictures. Chicago’s municipal father figure and then-longest-serving leader, Mayor Richard J. Daley, was probably typical. He only had a three books at home: the Bible, the Baltimore Catechism, and Profiles in Courage.

MAD Magazines, and even MAD Magazine books, don’t count—though we can stipulate that MAD was by far the most intellectually honest reading material in most homes.

So you see, there wasn’t all that much media available. Sooner or later, you ended up flipping through a newspaper whether you wanted to or not. Maybe you’d check it out because you sat down at the kitchen table with a sandwich for lunch, and because it was 1972, you didn’t have an extra TV in the kitchen much less a tablet loaded with episodes of your favorite TV show. But you can bet there’d be a paper nearby.

Newspapers were cheap and laying around everyone’s house. It’s not that everyone was smarter back then, or more concerned with learning about world events so they could be good citizens and vote intelligently. They were just people, like people any place, at any point in world history: they were looking for something to do. So I’m not saying they were any better than you, although it wouldn’t kill you to read more news.

What if you specifically wanted news back then, for itself? News is important, after all. As Thomas Jefferson wrote a friend in 1787, “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

In the 1960s and ‘70s, just as in Jefferson’s time, you couldn’t get news from computers via the internet. And you didn’t get all that much news from TV, either. Local TV newscasts broadcast for a half hour at dinnertime, right before the half-hour national newscast. The local news returned from 10 to 10:30 p.m., and then everyone turned the channel to NBC (Channel 5 in Chicago) to watch Johnny Carson on the Tonight Show.

The short-lived but remarkable Chicago Journalism Review examined the local 10 p.m. newscasts in 1970. After deducting time for sports, weather, and commercials, CJR found actual news lasted 12 to 14 minutes. That was it. No 24-hour news cycle, no nonstop cable news channels like CNN. It sounds nice, actually.

Radio news? As far as young Steve could tell, radio consisted only of WGN-TV’s sister station on AM radio—and WGN radio consisted almost entirely of the Wally Phillips morning show, because that’s what was on in Steve’s house. And young Steve was 75% right, too. WGN radio, 720 on the AM dial, covered 110 surrounding counties. One quarter of that audience listened to Wally Phillips—about 1.5 million people. Wally’s groundbreaking news on any given day was either the answer to Ellery Queen’s Minute Mystery, or random information from listeners who drove by a fire or car accident and then found a payphone so they could call it in to Wally. (No cell phones!) Useful information, to be sure, but of no lasting significance.

To recap: There wasn’t much to do back then, and you didn’t get a lot of news from TV or radio, not like today. There were no computers or cell phones. But there was always a newspaper laying around.

Now, what were those 1972 Chicago papers like, those ubiquitous pieces of newsprint thrown across everyone’s kitchen tables, left behind on train seats and restaurant chairs, or bundled up and dumped in the garage to save for a Boy Scout newspaper recycling drive?

When Steve was a kid, Chicago had four major daily newspapers, plus the smaller Chicago Daily Defender covered Chicago’s Black community. The major dailies were the Chicago Daily News, the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Sun-Times, and Chicago Today (formerly Chicago’s American). The Defender was a historically powerful force in the Great Migrations north of African-Americans from the South.

Besides a few papers in foreign languages still aimed at various immigrant communities, there were dozens of smaller neighborhood papers published weekly or twice weekly. Of these, Roselanders were most like to get the Calumet Index and the South End Reporter.

Since it was 1972, the “alternative” press was kicking in too, not that a kid like Steve was likely to see them at the time unless an older, very adventurous sibling actually brought one home. The Chicago Seed, a classic underground newspaper, published its counterculture and colorful content 1967-74. The Chicago Reader started in October 1971, and still hangs on as I write. As America’s gay community fully emerged following the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York, official gay newspapers were born— “gay” being the term du jour. But again, someone like Steve would never have likely seen a gay publication back then. The Chicago Gay Crusader published 1973-76, overlapping with GayLife 1975-1986, and followed by Windy City Times and Outlines in the ‘80s, which later merged and still publish online.

Back to 1972: The four major dailies were by definition at that time the white and male press, but you might be surprised to know that the papers had begun hiring Black reporters in the ‘60s, and ran some content aimed directly at the growing Chicago Latino community. The dailies even featured some regular local Black columnists by 1972, most notably Chicago journalists Lu Palmer in the Daily News and Vernon Jarrett in the Tribune, plus the nationally syndicated Carl Rowan. And a few women journalists like Lois Wille and Betty Washington had broken into regular news beats, too. So it was a fluid time; change was happening.

Nearly everyone Steve knew subscribed to one of the major dailies, along with at least one smaller paper. Paperboys for competing publications loaded their wagons or bike baskets with newspapers every day and covered a “route,” tossing the papers onto front porches if they cared about getting a tip for Christmas. If the paperboy didn’t care, he lobbed the paper into the ubiquitous evergreen bushes next to every porch. Though an occasional girl muscled her way in, they were nearly all paperboys. The word was not just a lingering figure of speech.

Some paperboys delivered the morning papers—the Tribune or the Sun-Times—in time for breakfast. Others went to work after school delivering the evening papers—the Daily News or Chicago Today. Mayor Daley read the Sun-Times and the Tribune in his chauffeured Cadillac, driving up the Dan Ryan expressway to City Hall every morning from his home in Bridgeport. Evenings, he read the Daily News and Chicago Today as the Cadillac took him to an awards dinner, a wake, or other function.

Not only were there different papers in the morning and evening, delivered right to people’s front porches, but each paper also updated itself in several different editions as the day wore on. In the first decades of the 20th century, actual human beings—newsboys--walked around hawking the late editions. In Steve’s day, the later editions were sold on the little newsstands that used to dot city street corners everywhere. Those editions sported colorful names like “Red Flash,” “Green Streak” or “Final Markets” on the top of the front page, just to the right of the masthead.

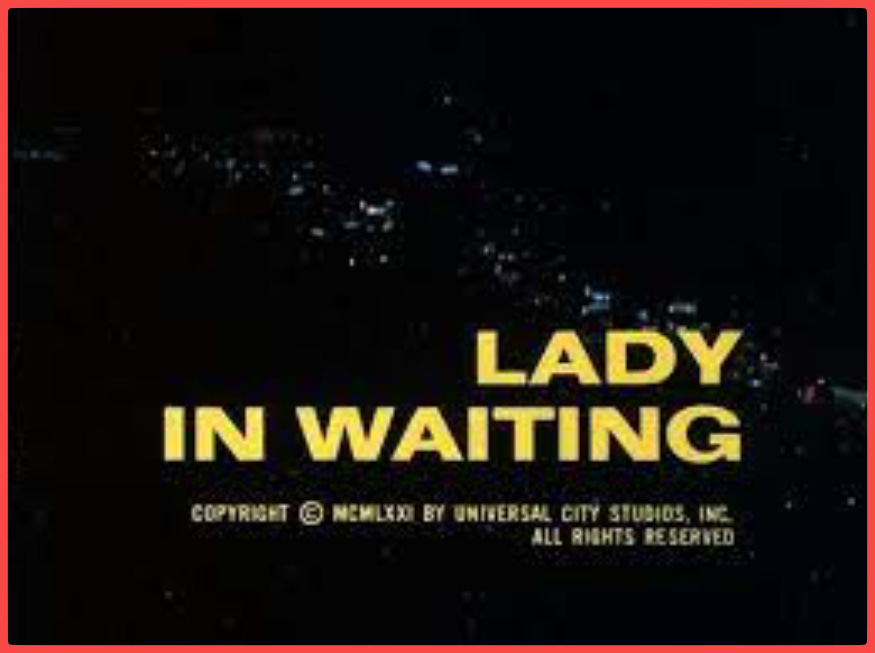

These were basic facts of life, understood and known by everyone. To illustrate, we turn again to the seminal first season of Columbo. Columbo aired on Ch. 5, by the way—on Sunday nights, one of three rotating series that made up the NBC Sunday Mystery Movie. Columbo was a whopping 90-minutes, a giant among 30-minute sitcoms and 60-minute dramas. In “Lady In Waiting,” Columbo solves a murder based on nothing more than a newspaper left on the front hall table.

We are, as always, in early 1970’s Los Angeles.

The main character is thirtyish, conservative, repressed Beth Chadwick.

Beth’s annoying older brother Bryce controls the family advertising firm and Beth’s life.

When Beth dates a lawyer in the family firm played by handsome actor Leslie Nielson, Bryce threatens to fire him.

Beth devises a plan to murder Bryce in the family mansion that night and make it look like she shot him accidentally, thinking he was an intruder. She steals Bryce’s front door key so he’ll come in that night through her ground floor bedroom’s French doors. She replaces the front porch light with a burned-out bulb so he won’t be able to see what he’s doing. Then Beth turns off her bedroom light and waits up in bed, holding her gun, ready to shoot Bryce.

Bryce arrives home carrying a newspaper and briefcase. He realizes he doesn’t have a front door key, and rings the bell. No answer. Now Bryce surprises Beth by getting in the front door anyway—he secretly kept a spare key in a plant outside.

Bryce leaves his newspaper and briefcase in the front hall and goes to Beth’s room to yell at her for not answering the doorbell. Irritated Beth shoots him anyway, drags his body outside her bedroom’s French doors, then fetches his briefcase from the front hall and throws it next to his body. She doesn’t notice the newspaper. Remember, newspapers were always laying around the house back then.

Columbo viewers saw this entire scenario play out on Dec. 15, 1971 before their hero, Los Angeles LAPD Lt. Columbo, arrived to investigate. That’s the immutable format for every Columbo episode: You see how the murder happened, then you see how Columbo figures it out. Columbo fans know the murder set-up is required in order to truly savor their hero’s powers of observation, but this portion of the show is still the equivalent of shoving vegetables down your throat so you’ll be allowed to eat dessert.

The Bertolucci family, including youngest son nine-year-old Steve, were watching Beth and Bryce that December Sunday night in the front room of their little yellow brick bungalow at 12426 S. Wabash in Roseland, on the South Side of Chicago. In Chicago, “front room” means living room. As the name implies, it is always in the front of the house or apartment, right inside the front door, behind the front window.

All eight Bertolucci’s mentally drummed their 80 fingers as they watched Beth shoot Bryce. They were waiting for the episode’s murder to finish, followed by the first commercial break, after which Columbo would finally show up.

Columbo was their hero. They were Italian, he was Italian. They were Catholic, he was Catholic. They were not much to look at, neither was Columbo. But in the end Columbo always showed the wealthy, educated WASPy uppercrust murderers that he was smarter. The Bertolucci’s liked to think they could do that too, if they ever actually met any rich WASPy people.

“You see?” Mrs. Bertolucci would say after an episode of Columbo, “We have such a wonderful heritage! We’re not a bunch of mobsters, we come from the Roman Empire! Who invented the radio? Hey! I said, who invented the radio?” She would call this after the various Bertoluccis dispersing throughout the small bungalow.

“Marconi-Marconi-Marconi-Marconi-Marconi-Marconi,” came the monotone, automatic answers from kitchen, bathroom and bedrooms.

“I hope you remember that every time you use the wagon! And now we have Columbo,” Mrs. Bertolucci would finish triumphantly. She meant their rusty old red Radio Flyer wagon.

But we’ve gotten ahead of ourselves. We’re only up to the first commercial break of this Columbo episode.

The second the first commercial started, eight Bertolucci’s jumped up to use the bathroom or get some pop and Jays potato chips from the kitchen, then race back before the show started again. There were no video recorders or DVRs, only live TV. A lingered moment at the bathroom mirror or seconds frittered away pouring Jays potato chips into a bowl could mean missing a vital clue if you were watching a detective show like Columbo.

Unfortunately, on December 15, 1971, five Bertolucci’s wound up jostling outside the bathroom door in the narrow central hall. Did I mention there was one bathroom? A Chicago bungalow has one bathroom located down the hall from the front room, midway toward the kitchen. A Chicago Catholic family like the Bertolucci’s consisted of far too many people for one bathroom.

When the jostling settled into a bathroom line, Steve was last. Did I mention Steve was the youngest? So naturally he was last.

As precious minutes ticked by, emergency measures went into effect. When oldest brother Richie exited and ran to the kitchen, Rocco and Frank, Steve’s next two brothers in age, ran in together and slammed the door over Mrs. Bertolucci’s loud protests. Everyone knew they were using the toilet simultaneously like a small public urinal. “Stop that! You weren’t born in a barn!” yelled Mrs. Bertolucci, pounding on the door.

As Mrs. Bertolucci pounded on the bathroom door, the three oldest Bertolucci brothers—Richie, Tony/Guido and Brownie respectively—were a few feet down the hall in the kitchen, dividing the contents of one bottle of Canfield’s black cherry pop between three glasses.

The goal was to create a period delicacy, the “Black Cow,” by adding one scoop of vanilla ice cream to each glass of black cherry pop. The obstacle: there were only about two scoops of vanilla ice cream left in the half-gallon carton of Sealtest ice cream, bought the day before by Mrs. Bertolucci at the nearby Home Store.

Richie aimed his spoon at the small hill of ice cream left in one corner of the rectangular cardboard Sealtest carton. Brownie perceived the danger. He grabbed the carton, drawing it back in one hand behind his head like an ice cream football.

“Guido! Go long!” Brownie yelled at Tony/Guido. He was poised to throw the Sealtest carton over the kitchen counter and across the tiny dinette.

“Don’t call him Guido!” yelled Mrs. Bertolucci from the hallway in front of the bathroom door. Guido’s name was really Tony. Brownie’s name was really Guido. We’ll cover that more thoroughly in Chapter 6: Sister Miller.

The dinette—more precisely, the short distance between the counter and the kitchen window--was just large enough to contain the horizontal width of the kitchen table.

“Go long?” said Richie, who never missed an opportunity for sarcasm. “Where daya think he’s gonna go, through the window?” “Wheredaya” was one three-syllable word.

Tony/Guido snapped to attention and dashed around the counter into the tiny dinette, turning as he slammed into the kitchen’s picture window and intercepted the Sealtest. He did, in fact, nearly go through the window. It was not long, but it was still a tricky catch, requiring Tony/Guido to squeeze past the kitchen chairs as he ran.

“Guido!” yelled Richie. “Give it back! The ad’s almost over!”

“No, I’m hijacking this ice cream to Cuba!” yelled Tony/Guido.

“Don’t call him Guido!” yelled Mrs. Bertolluci.

“Guido! It’s gonna melt!” yelled Richie.

“Let dad do the scooping!” yelled Brownie, as Tony/Guido chortled and danced around holding the Sealtest football over his head, safe behind the kitchen table.

“Goddammit,” grumbled Mr. Bertolucci, stomping into the kitchen. He grabbed the Sealtest carton from Tony. “Gimme that spoon! Gimme the ice cream!”

Tony/Guido shrugged and tossed Mr. Bertolucci the Sealtest carton. Mr. Bertolucci grabbed the spoon from Richie and swiftly dropped three stunted, roughly equivalent wads of ice cream into the three glasses of fizzing black cherry pop.

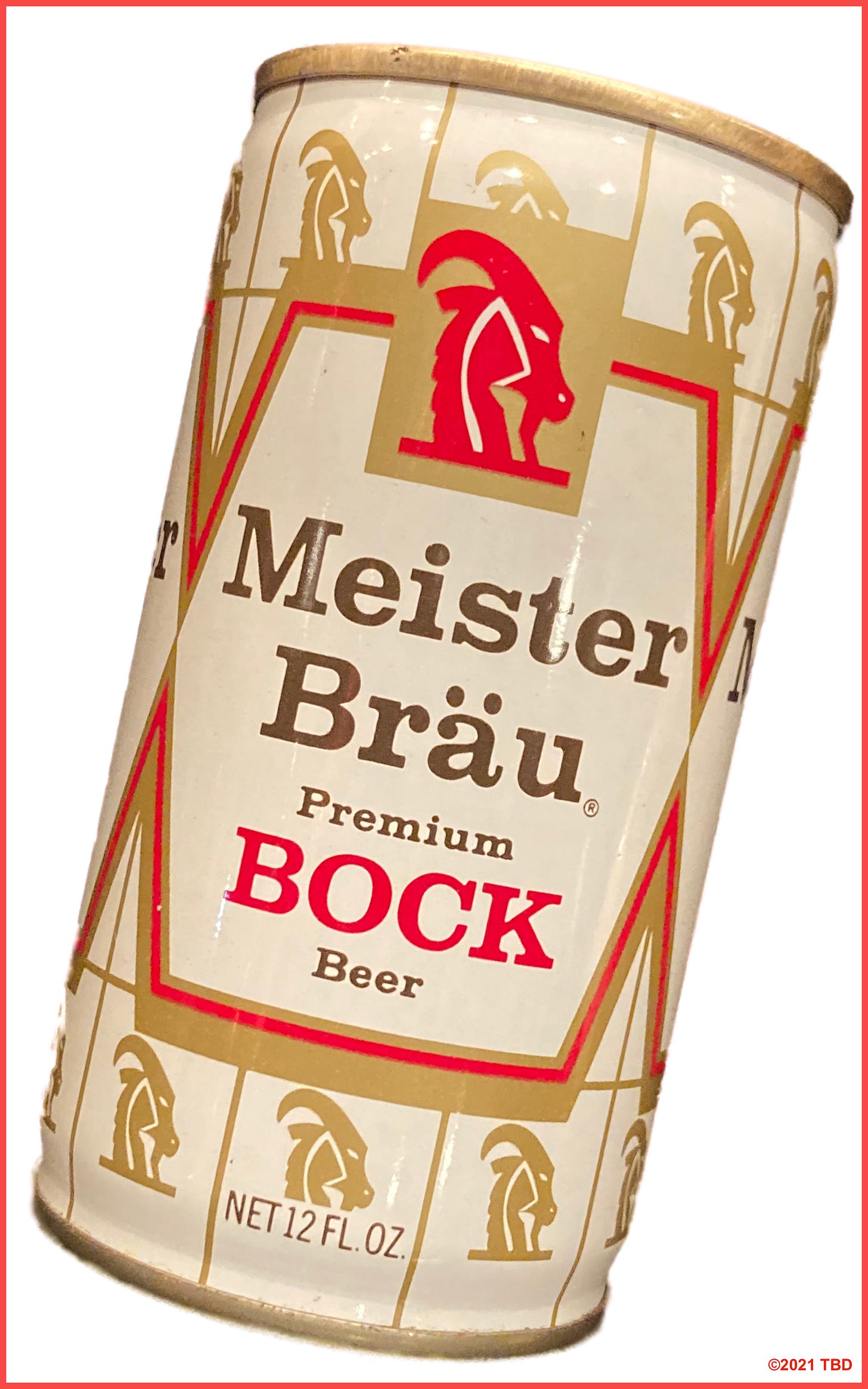

As Richie, Tony/Guido and Brownie/Guido raced to the front room with their Black Cows, Mr. Bertolucci picked up his Meister Brau can opener from the counter.

Mr. Bertolucci opened the refrigerator and stared inside, rubbing the can opener in one hand like a talisman. He yearned for the ice cold can of Meister Brau Bock beckoning from the middle shelf in the refrigerator door. It was the last of the 1970 Meister Brau Bock vintage.

Meister Brau was a Chicago beer, born and brewed. One out of every three beers guzzled in Chicago was Meister Brau, created in the company’s factory at North Avenue and Sheffield.

There was never a Meister Brau drought. But Meister Brau Bock was special--a traditional German spring brew sold for only a few weeks during Lent. Mr. Bertolucci hoarded cases of Bock all year under his basement workbench, rationing it carefully.

After the Meister Brau Bock was gone, Mr. Bertolucci switched to Meister Brau’s biggest seller, its true unpasteurized Draft beer. Never Meister Brau Lite, the first diet beer ever sold anywhere. Mr. Bertolucci never drank that. There were always a few six packs of the shunned Meister Brau Lite collecting spiderwebs and dead beachball bugs in the darkest corner under the work bench.

Why? Because Meister Brau Lite came in a pretty can with sky blue stripes.

That was Mrs. Bertolucci’s favorite color, and it also reminded her of the sky blue Westinghouse radio her childhood best friend had given her as a wedding present. Sometimes when she went shopping at the Home Store nearby on Michigan Avenue, Mrs. Bertolucci found herself unable to resist picking up the pretty sky blue striped Meister Brau Lite instead of a six-pack of boring brown Meister Brau Draft.

It was like Mrs. Bertolucci was hypnotized by the sky blue stripes on the Lite can. She was always surprised at Mr. Bertolucci’s anguished cries when he reached in a Home Store shopping bag and pulled out a pretty six-pack of Meister Brau Lite. “Now how did that happen?” she would say.

Now the last, lonely can of Meister Brau Bock glinted invitingly in the soft rays of the refrigerator light bulb. The majestic goat heads—the symbol of Bock beer—marched in circles around the can. They seemed to wink at Mr. Bertolucci.

But Mr. Bertolucci knew he wouldn’t get away with a beer on a Sunday night with the family in the front room. He took a bottle of Coke instead and savagely snapped off the metal cap with his Meister Brau can opener. He had nothing against the Coke. He just knew the can opener was as close as he was going to get to Meister Brau all night.

Everyone made it back to the front room by the end of the commercial break. Mrs. Bertolucci had let Steve use the bathroom before her, so he wouldn’t miss Columbo pulling up to Beth’s mansion in his dirty, rumbling old car.

Out of breath but back in the front room in time for Columbo, Mrs. Bertolucci held her usual glass of Canfield’s Gingerale pop.

Frank, Rocco and Steve feasted on Jays potato chips dipped in a tub of sour cream mixed with a package of Lipton’s powdered onion soup, an aromatic delicacy of the period known as “cheese dip” for no apparent reason since no cheese had been harmed in the making of the dip.

Frank had made the cheese dip. He was the cheese dip fiend of the household. Everyone who wanted cheese dip knew if they waited him out, Frank would make cheese dip any time there was serious TV-watching to be done. By Bertolucci common law, if one person made something that could conceivably be a communal food, they had to share. Frank didn’t have the option of making cheese dip for himself and forbidding others from dipping in a Jays potato chip.

“Why do I always have to make the cheese dip?” Frank would complain. He just didn’t get it.

Frank and Rocco guzzled Canfield’s strawberry pop. Canfield’s was the dominant regional soft drink manufacturer. In Chicago “a soft drink” or “a soda” is pop, with no preceding indefinite article. Steve sipped his favorite, Canfield’s 50/50, a sort of cross between 7-Up and Mountain Dew.

Mr. Bertolucci disdained the locally-produced Canfield’s pop. He drank mighty global Coca-Cola straight from the thick, sensuously-curved glass bottle. He drank, dreaming of the Meister Brau Bock can in the refrigerator and the winking majestic goat heads.

At Beth’s mansion, the Los Angeles police scurry around investigating the murder scene.

Columbo arrives and as always ignores the hubbub of the ordinary cops. He’s above all that. He picks up Bryce’s newspaper from the front hall table and examines the front page.

“You catching up on your reading, lieutenant?” a uniformed cop jokes.

“Not really,” mumbles Columbo, thumbing through the pages. He puts down the paper when the police gather around the supposedly distraught Beth, sniffling on the couch in the huge majestic living room in her bathrobe. She tells everyone how she stayed home all day, then went to bed and accidentally shot her brother.

“Did I hear you say you didn’t go out today?” Columbo interrupts. “You stayed home?”

“That’s what I said,” sniffles Beth.

The next day, Columbo comes back to the mansion. (He’s always coming back.) Over coffee poured from an elaborate silver pot, Columbo tells Beth he couldn’t sleep the previous night. There were a couple of points that bothered him. (There are always points that bother him.)

What kind of points, Beth asks politely.

“That newspaper,” sighs Columbo. “Didn’t I hear you say that you were home all day yesterday?” Beth confirms this. “See, that’s what puzzles me—how could that newspaper get here?”

“Haven’t you ever heard of home delivery?” Beth chuckles patronizingly.

“Yeah, I have the newspaper delivered to my house every morning,” says Columbo.

“There’s your answer,” says Beth.

“No, no that won’t answer it,” says troubled Columbo. “No, no the newspaper on the foyer table, that was a late edition. I mean, I even saw race track results in it.”

In other words, Beth’s morning newspaper in Los Angeles put out a late afternoon edition for the newsstands that listed winners from horse races held earlier in the day. That edition would never get delivered to anyone’s house by a paperboy early in the morning. You’d have to leave your house and stop at a newsstand to get it in the late afternoon or early evening. Which is what poor, annoying, murdered Bryce must have done on his way home from work.

In Chicago, the morning Sun-Times put out a newsstand edition with the latest information on that day’s races, called the “Turf Final.” Here’s the Turf Final edition from December 23, 1976, featuring coverage of Mayor Daley’s funeral after 21 years in office:

Back in LA, Beth pretends she doesn’t understand what Columbo is getting at, a common tactic among Columbo suspects.

“Well if you were home all day, who brought home the newspaper?” Columbo wonders.

Over the course of the episode, Columbo runs down some other little “problems” as he interacts with the other characters, like Beth and Bryce’s mom, played by the actress who played Cary Grant’s mom in North by Northwest. Bryce’s mom is way more concerned that Columbo might think Bryce was gay, than that Bryce is dead.

“He never married, did he,” Columbo muses. “Why was that?”

Bryce’s mom gets upset for the first time: “What are you implying?” she demands.

“Oh, no offense m’am,” Columbo quickly apologizes.

Beth gets her hair cut and buys cool new ‘70s clothes, so now we really know she’s a bad girl. Also she gets bossy and wants to run the family company.

Columbo finds a few more incriminating points—the lightbulb over the front door shouldn’t have burned out so soon, for instance. Ultimately, though, as Columbo tells Beth when he arrests her, “I knew it wasn’t an accident the first night. I knew it as soon as I saw that newspaper, but I didn’t have any proof. I hadda wait for the proof.”

Like Columbo, everybody Steve knew got one of the four major daily newspapers delivered to their house. And newspapers were a bit like people, even relatives. What kind of folks did your family hang around with? Besides the more targeted or local papers like the Defender or the Calumet Index, did they eat breakfast with the Sun-Times, or the Tribune? In the evening, who did your family invite inside to sit in the front room, the Daily News or Chicago Today (formerly called Chicago’s American)?

Your own newspaper—the typeface, the width of the columns, the style of the headlines—looked as familiar and natural to you as your mom’s face. Reading someone else’s paper was like seeing mom with a different pair of glasses or a nose job.

The Tribune was sometimes like having conservative, cantankerous 20th century editor/publisher Colonel McCormick hanging around your house, even though he’d died in 1955. The Daily News was like a TV uncle or dad who’d gone to college. He wore nice cardigan sweaters with leather patches on the elbows, smoked a pipe, and told you about all the interesting places he’d been. The Sun-Times was your scrappy aunt who didn’t make it to college, but she’s no-nonsense streetsmart. And Chicago Today was that fun cousin who told great stories sometimes, but then he’d get drunk and ruin a family party every once in a while.

We’ll explore each of them further in the second part of Chapter 3 Notes. For now, we’ll just note that Studs Terkel (1912-2008) read the Daily News, which doesn’t make it perfect, but counts as a certain stamp of approval. Wouldn’t it be nice to have Studs Terkel on Twitter today as an influencer? Oh well.

Steve’s family read the Daily News, and if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko. At the Bertolucci’s, “Where’s Royko?” and “Where’s the paper?” asked the same question. Nothing was more disappointing than flipping to page 3 in the Daily News and seeing the brief message “Mike Royko is on vacation” instead of Mike peering down the page from above his column.

People thought the advent of radio in the early 20th century would kill newspapers, but it didn’t. Rather, television appeared in the late ‘40s and by the ‘50s it had teamed up with radio to begin slowly choking off the financial oxygen of newspapers—advertising. As young Steve began blinking at the world around him, newspapers were still fighting back, gagging and flailing. The weaker ones went down first. Let’s say half survived into the ‘70s and ‘80s. The internet snuck up on the survivors in the ‘90s and early 2000’s, wrestling the newspapers to the ground and pressing a virtual foot on their necks.

Then came the private equity investors—buying newspapers, dismembering them like barnyard chickens, and selling off anything valuable while they slashed staffing levels. As I write this, the Sun-Times Building has been gone for over a decade, replaced by Trump Tower. A few blocks away, Tribune Tower is almost done morphing into condominiums.

The Tribune’s dwindling staff moved initially to nice digs in the Prudential Building, but in early 2021 the paper announced a further move to its Freedom Center printing plant on Chicago Avenue, west of Halsted.

The Sun-Times’ dwindling staff was sent west of the Loop on the third floor of 30 N. Racine, literally above a Good Will store. It’s one of the nicest Good Will stores you’ll ever visit, for what that’s worth.

Above, the old Sun-Times newsroom (courtesy of the Newberry Collection); below, the Sun-Times newsroom circa 2021 (courtesy Google Streetview).

Happily, the Sun-Times snagged a new lease on life in 2022 when it was acquired by Chicago’s public radio station, WBEZ. Since the paper was losing money, we’ll see if a nonprofit radio station can pull in enough foundation grants annually to keep plugging the budget holes, and whether the Sun-Times newsroom will remain editorially independent. Fingers crossed!

Unfortunately, the trend across the country has gone in one direction for decades. One by one, the papers are blacking out. I wonder if there are any left now, as you read this. Even a newspaper can only hold its breath for so long.

In any case, we’ll always have the microfilm. Here’s where I have to say a big thank you to Gil from the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library microfilm room, my gentle guide through the underworld of Steve’s past, who kindly refilled the paper tray and toner in the microfilm copier for me so many times. Once he got to know me, Gil would check my machine’s paper and toner before he went off to a long meeting, so I wouldn’t get stranded in the middle of a decade. That’s the kind of thing that sticks with you.

“You reading Royko?” Gil said one day, stopping to look at the microfilm machine’s glowing screen over my shoulder. “Best newspaper columnist there ever was. Probably the best there ever will be, you ask me.”

I was reading Royko from April 1968, on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s announcement that he wouldn’t run for re-election. LBJ was pretty unpopular at that point, but Mike was not one to cater to his audience.

“The president of the United States told the people of the United States they are so divided against themselves he dares not take part in a political campaign for fear that it could get even worse,” Mike wrote. Then he described how everybody hated LBJ. “Every smart punk grabbed a sign and accused him of being in a class with Hitler or mass-murderer Richard Speck….Maybe he wasn’t the best president we might have had. But we sure as hell aren’t the best people a president has ever had.”

“A lot of people hated Royko too, right?” I said.

“Yeah,” sniffed Gil. “Like I said, best columnist ever.”

Another great thing about Gil is that he wears colorful Hawaiian shirts to work. If you’ve ever spent time in Regenstein library, which looks like an underground bunker that got excavated and left baking in sunlight to which it was never meant to be exposed, you know how helpful it is to see a cheery bit of color in there. “Regenstein” rhymes with “Frankenstein” for a good reason: the place is a monster. In the belly of that monster, Gil’s walrus moustache and his Hawaiian shirts provided some small but crucial comfort.

Outside Regenstein, I was so possessed by my quest to find the real Steve, I even talked to Steve himself. And I finally heard what he told me, rather than using my normal system of routing everything he said through an algorithm in my head to convert his words into my own imagined gibberish.

I talked to Steve in the only way I find you ever really communicate with anyone: in casual bits and pieces while you’re cleaning the basement, or sitting on a bench watching kids play soccer, or putting ornaments on a Christmas tree. The times when no one feels pressured to say anything at all, much less communicate the deepest secrets and longings of their soul. And if anyone does end up communicating the deepest secrets and longings of their soul, you don’t make a big deal about it. You just nod and keep sweeping the floor, or hang up another ornament. You both know what’s been said, and you both know you both know, and that’s enough.

But why should I go to so much trouble finding out about Steve? He’s not famous. He’s not important, outside the web of people woven into and around his life.

That’s why. That’s exactly why.

If Steve was famous or important, he probably would’ve spent his life making himself famous or important. You get that, right? Hardly anyone becomes famous or important by accident. What Steve spent his life on--to the rest of the world, to the rest of the universe--could not be more trivial. But if Steve spent his life making himself important, he wouldn’t be important to me.

Is this making any sense to you at all? Let me try again. Let’s go back to the library. Because Gil completely disagrees with me on this whole famous and important thing, so you may not be on board with it either.

When I was scrolling through all that microfilm, the most interesting stories were one- or two-paragraph tidbits stuck at the bottom of a page to fill up space. Take April 20, 1972 in the Sun-Times, a miniscule jotting with a dateline from Champaign-Urbana, home of the University of Illinois: “Enema Bandit Attacks 3 Co-eds.” Some guy in a ski mask broke into an apartment with a gun, tied up the three women living there, and gave them enemas.

Here’s the part that really got me, tacked on at the end: “The attacks were similar to at least 10 others in the last year, police said.”

Ten others in the last year. This guy forced enemas on at least ten other complete strangers, and they still hadn’t caught him. Unbelievable. And by the way, anyone who’s ever experienced an enema understands it’s not something anyone “gives” you.

Most people would have missed the Enema Bandit story on April 20, 1972 when they were flipping through a real paper copy of the Sun-Times over breakfast or on the train. Like I said, it was just a few sentences, buried at the bottom of the page. And you only see something like the Enema Bandit story now if, like me, you’re looking for something else but you can’t help stopping for a crazy headline. To anyone who encountered the Enema Bandit, to their family and friends, that was the biggest story of the century. But to everybody else outside central Illinois, it was a blur of ink as they turned the page.

Sitting in the dark, muffled quiet of the Regenstein microfilm room, at some point my mind began to feel like it was vibrating, just thinking about all the lost bits and pieces of life stored on the microfilm, filed ten or twelve reels deep, rows upon rows, on all the shelves of the floor-to-ceiling bookcases lined up behind me on Regenstein’s third floor for literally half a city block. How with the advent of the internet there’s so much more life piling up in cyberspace, probably the equivalent of an entire library of microfilm every single day, or maybe every single second.

The vibrating brain thing would come back every now and then as I worked in the microfilm room. One dreary winter morning I picked out a microfilm reel of Chicago Today from 1969. It was the first time I’d picked out Chicago Today instead of the Daily News or the Sun-Times. I sat back down at the microfilm machine and took the reel out of its box.

There was a rubber band wrapped around the microfilm reel. I’d never seen that before. I took it off and stretched it between my fingers, contemplating the anomaly.

The rubberband was thick and tan, taut enough to use for strengthening exercises after you have a stroke. As always, I turned to Gil for answers. I stood and twisted to look over my cubicle wall and check his office, in the southwest corner of the room, behind a soundproof glass wall. The chair behind the desk was empty.

I started turning back and yelped: Gil’s bushy moustache was practically tickling my chin. For a big guy, he moves surprisingly silently over the gray industrial carpeting. At one point early on, I questioned whether Gil even cast a shadow. Then I realized there’s just no light in the microfilm room. Or rather, you can see, but there’s no discernible point of origin for the weak illumination, and it makes no more headway than shining a flashlight into a plume of thick black smoke.

“Jesus Christ, you almost gave me a heart attack,” I said.

“Sorry,” shrugged Gil. “Doublemint?” He held up an open pack of Doublemint gum. I knew it would leave my mouth feeling like dried cement, but I took it anyway. I realize now: people like to give you things, even if it’s just a piece of gum.

I stood there shaking my head for a minute, holding the gum. It’s a little embarrassing, getting scared to death by a librarian with red, green and blue parrots flying across his shirt.

“OK, let’s hear it,” said Gil, looking at his watch. “I know it feels like eternity here but we’re still on the clock.”

I held up the reel. “I was wondering…”

“Why that Chicago Today has a rubberband around it.” Gil finished my sentence, another habit of his.

“Uh, yeah.”

“They come that way.”

“You mean Chicago Today microfilm comes with a rubberband?”

“No, they all come with rubberbands.”

They all come with rubberbands. But after going through boxes and boxes, I had never seen a rubberband before.

“What do you mean they—“

“OK, I'm looking at how much film you want to get through today,” Gil interrupted, nodding at the tottering tower of square boxes next to my microfilm viewer. “Whaddaya care about rubberbands? Focus, or you’re never gonna finish this nutty project of yours. Not that I don’t enjoy your company.”

He was right, but only in the most concrete sense. I dropped the rubberband, and picked it up again as soon as Gil moved on. Gil is terrific, but he doesn’t know everything. Nobody does.

I twisted the rubberband into a figure eight and contemplated it. There was only one answer, really. The presence of a rubberband on the microfilm meant nobody had ever looked at that reel before. Someone put the rubberband on at the microfilm factory in 1969, and there it stayed. For all the other reels I’d scrolled through, at least one person had, at least once, opened the box, pulled out the reel, peeled off the rubberband, and run the reel through the microfilm machine. Then they pitched the rubberband. No one bothers putting the rubberbands back on, the same way no one ever rewound videotapes if they could get away with it, back when there was videotape.

As an absolutely useless social experiment that I will almost certainly never complete, I put the rubberband back on the Chicago Today reel when I was done, so I could go back in 20 or 30 years and see if it’s still there. Like a detective in a 1940s film noir, slipping a scrap of paper in a door so they’ll be able to tell if anyone goes through it. But I know the rubberband will be there. I never had a lot of company in the microfilm room. Hardly anybody goes there anymore.

Nobody on Earth cares about the little things that happened to some poor schlub in 1969, unless you get a big movie star to play them. Nobody cares about the Enema Bandit. In the future, when we’ve devastated Earth and died out as a species, no one in the universe will know there was an Enema Bandit or a 1969. And I get it—there’s only so much time. You can’t obsess about every little minute of the past.

This doesn’t make me feel like all that news, all that life, was pointless, an insignificant drop in the vast pool of time. It makes me feel like it’s even more important. It makes me want to take that Chicago Today microfilm reel home and give it a place of honor on the coffee table. Or build a special cabinet, place the microfilm reel carefully inside on a thick tempered glass shelf, and flick on an interior spotlight.

Maybe you don’t agree, but that’s how I feel about it, and that’s how I feel about Steve. Gil and I really had it out over this one day. Gil maintained if you don't make some huge, indelible mark on the world that everyone celebrates, recorded for posterity in history books, then your legacy is, to quote the mighty philosophers of the 1970s rock group Kansas, dust in the wind. To which I retorted, where do we get off making dust a universal symbol of insignificance? The whole world is made out of dust.

Gil was unwilling to concede my point, so I made him watch a Stephen Hawking video on YouTube about the formation of the solar system. Gil watched that video like he’d never heard of the Big Bang, perhaps because whoever narrates videos for Stephen Hawking has such a fabulous uppercrust British accent. This accent is so robust, so full-bodied, it practically pulls you in with its own gravitational field.

So this incredible accent explains that an old star blew up and formed a tremendous cloud in space called a nebula. Eventually gravity made “vast spirals of dust” form. At the center of one dust spiral, Earth took shape, “built by stardust and assembled by gravity.”

There you have it. Dust isn’t important? You’re standing on it. You evolved out of it. Sorry, Gil. But really, like you never heard Woodstock? The Crosby, Stills & Nash version of the song is the one most people know, but it was really written, and first performed and recorded, by Joni Mitchell. “We are stardust, we are golden,” she sings.

Anyway, the fact that Steve is important to me and everyone who knows him is probably still not important to you, because you don’t know him yet. Even now, even after everything I’ve told you about Columbo and newspapers and cheese dip and Canfield’s 50/50. That’s what this book is for—and to describe how Steve’s life was nearly ruined in a meeting inside St. Anthony’s church in 1972, and how that incident came back to haunt him in 2003.

For Chapter Four, we’ll rejoin Steve in 2003, this time on Sunday October 5, not long before he will receive the two black eyes that will astound his colleagues at Rose & Rose when he returns to work on Monday. (FYI if you read this chapter first, Steve’s Monday morning with two black eyes is covered in Chapter Two: The Conference Room Windows.) Fair warning, in Chapter Four we won’t stay with Steve long enough on October 5 just yet to see how he got those black eyes. All in good time. First, Steve will take a detour himself to 1972, and Gately’s Peoples Store on the Ave.

Next: Chapter 3 Notes, featuring notable topics including Gilligan’s Island, Mad Magazine, and the Enema Bandit

Next month, Chapter 4: The Gately’s Doughnut

In which Steve’s Nonna, a Gately’s doughnut, and a Roseland Little League All Stars baseball hat conspire to teach young Steve the heartbreaking truth, that you can’t have everything.

I don't remember the Enema Bandit, but I do remember the Ketchup Kreep. He skulked around the U of I library in Champaign & looked for co-eds [as they were called then], who were studying with their shoes off & poured ketchup into their shoes & then the women would put their shoes on & realize what happened. I never read that he was caught. There are some seriously strange people out there, but at least then, they rarely used guns.

My household got the Daily News. After it folded, we mostly got the Trib, and sometimes I'd see a Sun Times. Their comics were weird. Like you, precocious me loved Royko. Didn't always get the nuances of the issue of the day he'd address, but I loved his sharpness, his sneer, calling it like he sees it, putting the fat cats in their place. Aldercreatures! Never thought much about how he influenced me as a thinker and consumer of news (not to mention a writer), but for sure he did.