Note: If you’re a new reader, start with CHAPTER ONE: A GOOD LIFE RUINED or even the ABOUT page—and see you back here soon. To access all site contents, click HERE.

Unnecessary But Motivating Chapter Quote:

It is claimed that from the beginning of time he foresaw everything that would happen in the world. If that is true, he foresaw that Adam and Eve would eat the apple; that their posterity would be unendurable and have to be drowned; that Noah’s posterity would in their turn be unendurable, and that by and by he would have to leave his throne in heaven and come down and be crucified to save that same tiresome human race again. The whole of it? No!....None of them at all except such Roman Catholics as should have the luck to have a priest handy to sandpaper their souls at the last gasp, and here and there a Presbyterian. No others savable. All the others damned. By the millions.

-- Satan writing home to his pals, the archangels Michael and Gabriel, in Mark Twain’s “Letters from the Earth”

Time: 8:15 a.m., Sunday, October 5, 2003

Place: Steve’s front porch in Hyde Park, a little over 54 blocks south of his office in the IBM Building.

Weather: Sunny, 52 degrees Fahrenheit, cooler by the lake.

It was the gum.

A big grayish-white wad of gum stuck flat on the sidewalk, still fresh. A sheen of saliva covered the gum and glinted in the early October sun. Teeth marks rose in a ridge along its back like the armored plates of a stegosaurus.

To Steve, the gum might as well have been a severed head.

That is, Steve saw a typical, run-of-the-mill blob of chewed-up gum on the sidewalk, but he reacted to a severed head. He had no idea what was happening. But you, dear reader, instinctively understand why Steve might massively overreact to a mundane urban irritation like gum on a sidewalk. Don’t you?

The gum reminded Steve of a long-dead childhood memory, the kind best left buried under tons of concrete and a steel sarcophagus the size of a football field, like a personal Chernobyl. Don’t we all have memories like that? Alas, yes. Childhood is overrated. Childhood is as dangerous as a badly designed, poorly operated, aging Soviet nuclear power plant.

The grisly visual stimulus shot straight from Steve’s eyes to the tiny almond-shaped part of his brain we call the amygdala, which in turn activated his hypothalamus and every possible automatic fear response his middle-aged body could muster. If Steve harbored a traumatic childhood memory that actually did involve a severed head, his amygdala could not have performed more admirably. Dozens of stress hormones spurted into his bloodstream. For a moment, he stopped breathing.

In that moment, his lungs stilled, Steve’s body remained on his front porch in Hyde Park in 2003 while his soul, or his consciousness, whatever you want to call the essence of Steve, soared back to 1972.

Too dramatic? Fine. Let’s just say he remembered 1972:

Roseland, his old neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side.

St. Anthony of Padua Roman Catholic Church and Grammar School, 115th Street and Prairie Avenue.

The start of a mystery that would dog Steve his entire life. And that is not too dramatic, so I won’t rephrase it.

The malignant presence that terrorized St. Anthony’s that steamy spring was forever unidentified, but not unnamed. Every child there learned one indelible lesson:

The devil is real. He takes many shapes. And he lived among them.

Steve Bertolucci--41 years old, father of three, head of the tax department for the accounting firm Rose & Rose on the 14th floor of the IBM Building between State and Wabash on the north bank of the Chicago River, third office on the right past the conference room—stood on his front porch in his new neighborhood, Hyde Park, and blinked down at the gum on the sidewalk below.

His porch was at the corner of 54th Street and East View Park, a one-block street on the South Side overlooking Lake Shore Drive and beyond that, Lake Michigan.

He willed himself back to the present.

He realized his lefthand fingers were currently engaged in rubbing the thin brown ribbon of the scapular around his neck. He instantly disengaged those fingers, pushed the scapular ribbon back under his shirt, and let the hand drop down to his side.

“It’s probably Spearmint,” Steve thought, the deduction flowing from the gum’s grayish-white color, even though he knew gum was all pretty much the same color no matter what they called it or what color the packaging, especially once it got chewed. It wasn’t even necessarily Wrigley gum—there were plenty of other gums in the world.

Forget it. No time for gum, Roseland, or 115th Street in 1972. He needed to get to the French bakery before the chocolate croissants sold out. The chocolate croissants were vitally important, procuring them every Sunday morning a meticulously planned operation. They were chocolate.

It was a beautiful Sunday morning in early October. To be precise, this is the day before Steve showed up at work with two black eyes in Chapter 2. Steve had slept in, getting up with the chirping American Robin stationed at 7:00 on his Audubon Singing Bird Clock. Usually he was up by 5 a.m. with the honking Canadian Goose; if it was tax season, by 2 a.m. with the trilling American Goldfinch.

He’d found 7:00 very pleasant that day, lying in bed comparing the clock’s robin song with the actual robins outside his window. For once the neighborhood crows weren’t drowning out the real birds, as Steve thought of any bird that was not a crow. The crows liked mobbing together in one or two trees, cawing like a demented crowd at a monster truck derby. Real birds didn’t caw, Steve felt. They chirped and whistled. There was no crow on the Audubon clock. Who would want to wake up to that?

Now, on the porch, Steve refused to let a disgusting gob of gum spoil a beautiful, chirping, glittering fall Sunday. “It’s just a piece of gum,” he told himself. “So what? I wonder if Amy still has that Juicy Fruit necklace she used to wear.” Funny how insignificant things like cheap promotional necklaces rattle around our heads for decades.

It didn’t work. His soul already felt endangered because Steve knew he was about to skip Mass.

“Would Vince do that?” he thought. “No,” he had to admit. Vince would not do that, not ever. Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi had been that most hallowed form of lay Catholic, a daily communicant: He’d attended Mass and received the body of Christ every single day of his life in the form of a thin, round white wafer technically called “the Eucharist” but more commonly known as “Communion.”

With a twinge, Steve remembered that as an adult, as a Super Bowl-winning adult football coach, Vince would sometimes serve as an alter boy at the 8:00 mass he attended every morning in Green Bay.

Steve knew all too well that he himself had not served as an altar boy since 1972.

Steve shoved his hands into the front pockets of his navy blue Bears jacket. He was just tall enough that no one considered him short, and not quite tall enough for anyone to describe him as tall. Nonstop sports from childhood through having children himself had left Steve with a good build, now obscured by a slight spare tire because he no longer had spare time for sports. His deep brown Italian eyes could easily have been called dreamy, if he had leisure anymore for dreams.

Now his left hand came out of the Bears jacket left pocket to tug the collar of his white Hanes undershirt, peeking out of the opening left by the undone top button on his yellow polo shirt. This was as daring as Steve’s wardrobe got. His Land’s End plain front chino pants were just the shade of khaki that constituted no color at all. Land’s End called it “stone.” He resisted the temptation to let those lefthand fingers snake under his undershirt collar and seek out the thin brown ribbon of the scapular again.

Steve bent and checked the laces of his white gym shoes: Good. A tight double-knotted bow. He brushed back his short, thick dark brown hair, neatly parted on the side and politely skirting his ears by a wide margin. The thumb and forefinger of his right hand lingered for a moment on his stunted right ear. He adjusted his glasses and glanced down.

The gum was still there.

Steve wavered on the edge of the top step, eyeing the gum. He wondered if Nonna, his grandmother, would have called the gum bad luck. It sure felt like bad luck.

BAM.

Steve’s amygdala fired up again, catapulting him back in time once more—and still further this time, to 1967, thanks to Nonna.

i. Nonna

Almost anything was bad luck to Nonna. The number “17” was bad luck in Italy, and America too. In Italy, gravestones often carried an epitaph that looked like a slight rearrangement of the Roman numerals for “17.” Nonna didn’t know Latin, but she knew gravestones meant dead people, and dead people had by definition suffered some very bad luck.

In America, the regular numerals for “17” look like a man hanging from a gallows, the kind Americans draw to play a game of hangman. Nonna didn’t play hangman herself, but she’d seen the grandchildren play it, and that was enough.

“Why is it bad luck to die?” Steve’s oldest brother Richie would argue. “We’re Catholic. Aren’t we going to heaven automatically? Isn’t that supposed to be good?”

Richie was the only Bertolucci grandchild who bothered arguing with Nonna. You remember Richie; he was one of the three brothers who had a Black Cow during the first commercial break of “Columbo” on Dec. 15, 1971, when Beth shot her irritating brother Bryce.

“It’s good if you’re a hundred years old!” Nonna would yell. “You can’t ask God for more time than that! If you die before 100, that’s bad luck!”

“Maybe God wants you to die before you’re 100!” Richie might shoot back, racing down one of his many alternative routes for this recurring fight. “You know what God wants?”

Nonna would be ready for him. She was always ready.

“Yes!” Nonna would yell.

“Oh right, you know what God wants!” Richie might try next. “Prove it!”

“Prove I don’t!” Nonna would yell, whacking the counter triumphantly with the nearest wooden kitchen spoon. “Now go get a goddam haircut!”

No matter how often Richie started this or any other argument with Nonna, no matter how many surprise turns he took, he could never find a path to victory…except once, in the dark summer days of 1967, when he would wish so desperately to be wrong. More on that later.

Other numbers were trouble for Nonna too. The number “13” was good luck in Italy, but it was bad luck in America. In this one thing Nonna instantly ditched the land of her birth and embraced the New World wholeheartedly. “We’re American now,” Nonna insisted to others who clung to the old ways regarding thirteen. “What are you, a stupid peasant? Wise up! Here, thirteen is bad!”

Numbers were only the beginning. If you got home and put your hat on the bed, you were as good as dead. If it was hot and you opened a window, a nice cool draft of air was bad luck and could kill you. If a bird flew in the open window, someone in the house was going to die.

“Nonna!” Richie would argue. “Everyone in every house is gonna die, it’s only a matter of time.”

“So what?” she’d yell. “You wanna die now? I didn’t think so, close the damn window!”

Richie would realize that Nonna had somehow outsmarted him once again, and close the window.

Nonna’s chief weapon against bad luck could be found always on her wrist--a ponderous, clanking charm bracelet. The thick silver chain links carried a dizzying array of objects and symbols, all freighted with special powers and meaning.

Some charms looked completely random, like the dog on a leash. These were the most versatile—Nonna invented new meanings for these charms as the need arose. Other charms were easily interpreted, such as the crucifix and the St. Jude medal. There was a tiny state of Kansas, because Nonna and her family had first settled in tiny Frontenac, Kansas so the menfolk could work as coal miners.

The silver frame with a picture of Nonno was the most powerful, an all-purpose charm sure to ward off anything but Satan himself.

But even Nonno’s picture charm could not ward off the Depression. So banks were supremely bad luck, since Nonna and Nonno had lost what little money they had when the Roseland State Savings Bank closed on July 6, 1931. And when you have almost nothing, a little money is rather important. By 1932, national income had dropped 50%, unemployment reached 25%, and investors were willing to pay the U.S. Treasury for the privilege of investing in Treasury bonds—negative interest—because it was the safest thing to do with their money.

Nonna and Nonno were hardly alone in their financial misery. Fellow South Sider Leonard Japp and a partner had managed to buy an old truck in 1927. They gradually worked up to 15 trucks supplying cigarettes, sandwiches and potato chips to Al Capone’s speakeasies--until the stock market crashed on October 29, 1929. The South Side’s Casper State Bank failed, and Leonard Japp lost everything, just like Nonna and Nonno. It would be years before Japp worked back up to delivering snacks, finally founding Jays Potato Chips and thus providing Steve’s friend Bill with his typical weekday breakfast at Rose & Rose in 2003.

“Chicago area banks suffered one of the highest failure rates in the US, especially in the first halves of 1931 and 1932,” notes Natacha Postel-Vinay of the London School of Economics in her study “What Caused Chicago Bank Failures in the Great Depression? A Look at the 1920s.” “Indeed, out of 193 state banks in June 1929, only 35 survived up to June 1933.”

Nonna spit on the sidewalk whenever she passed a bank or a savings and loan association. The technical differences between financial institutions meant nothing to Nonna. When the Bertolucci’s watched “It’s A Wonderful Life” at Christmas, Nonna yelled that everybody should have taken their money out of the Bailey Brothers Savings and Loan when the Depression hit Bedford Falls; the Bedford Falls bank closed its doors; town despot Mr. Potter bought out the bank and offered fifty cents on the dollar for every share in the Bailey Brothers Savings and Loan, hoping to gain a controlling interest; and George Bailey begged his Savings and Loan customers to stand together against Mr. Potter, keep their shares, and withdraw just enough money to get by for a few days, until the bank reopened.

“Nonna!” Richie would argue. “If everybody took all their money out of the Savings and Loan, then Mr. Potter woulda owned the whole town!”

“He owned it all anyway!” she’d yell, and as so often happened, she was just right enough that Richie would be stumped.

Richie couldn’t argue with Nonna about banks because she remembered. She had been there, she had seen.

She knew, and he did not, what it was like to walk around the corner by your own home and smack into a mob of desperate people surging around the local bank like the roiling waters of a broken dam. So many people, there should have been Andy Frains keeping order, the way they did at baseball games at Comiskey Park and Wrigley Field, at the Chicago Stadium for the Blackhawks, and for all the other big events in town. Andy Frains were ushers named for ushering firm founder (and South Sider) Andy Frain. Andy Frains were at least six feet tall, well-built and well-groomed in their blue military-style jackets with the gold braid, shiny black polished shoes and smart matching caps set firmly atop indisputably short hair. Andy Frains were unfailingly polite, but always ready for a tussle.

Like city garbagemen, Andy Frains did Chicago’s dirty work. They reasoned with drunken Sox fans and herded escaped sheep in hallways or off Halsted during the annual International Livestock Exposition at the Amphitheater. Chicagoans expected Andy Frains to keep State Street parade crowds on the sidewalk and Beatle fans off the stage (again at the Amphitheater).

But there were no Andy Frains organizing lines at failing banks during the Depression. No Andy Frains directed hysterical people to the nearest box office where they could get their money back.

No one got their money back. No one Nonna knew, anyway. Nonna—and her money—never crossed the threshold of a bank again.

No one knew where Nonna kept her money instead of the bank, including Nonno. Nonno drove a Magikist Rug Cleaners delivery van plastered with the Magikist logo, a pair of giant flaming red lips. Nonno had arrived in America an unschooled peasant with no money and no English. Now he had heavily accented English, but he still had very little money. He got by on customer tips he hid from Nonna, who never revealed what happened to his modest Magikist paycheck after he handed it over to her. Steve and his brothers spent hours searching for Nonna’s money in her tiny apartment above a hardware store and a bar on 115th and Prairie, around the corner from St. Anthony’s. The place was a nonstop game of treasure hunt.

That was fine with Nonno. When the grandchildren came over, he got a nice cold Meister Brau from the refrigerator and settled down at the kitchen table. “You keeds loooook for your treasurrrre,” he would chuckle in his thick accent, rolling his r’s as hard as a championship bowler. “I got my treasurrre right heeerrrre!” Then he’d crack open the Meister Brau and take the first cold foaming draught of it, surveying the foraging children as if he and the Meister Brau were factory foremen overseeing a shift of workers. Whatever kind of Meister Brau Nonna bought at the Home Store, Nonno drank: Bock, Draft, Premium or even Lite. He had learned to save his objections for truly important subjects, and few things were ever important enough to cross Nonna.

But the treasure hunts drove Mrs. Bertolucci nuts. “Nonna doesn’t even have any money,” she insisted as the kids threw seat cushions everywhere and rolled up the mismatched rugs abandoned by Magikist customers who, for whatever reason, had never paid their cleaning bills. “If Nonna had money, would she still be living in this crummy place, on top of a hardware store, looking out at the alley?”

The kids ignored her. Mrs. Bertolucci’s logic persuaded no one. They thought it would be great to live on top of a hardware store and a corner bar, with a busy, interesting alley instead of a tiny boring backyard. And the apartment didn’t look crummy to them, since Nonna made Nonno paint it every few months with the free paint she made Steve’s dad bring home from his job at the nearby Sherwin-Williams paint factory.

Nonna’s broad, open face was either staggeringly happy and bursting with love, or contorted into unfathomable rage capable of decimating entire civilizations. There was little in between. Her beady eyes peered out from behind crooked neutral-colored plastic frame glasses with lenses that were permanently smudged even when brand-new. Nonna’s four-foot, eleven-inch frame housed the strength of a giant underneath an unruly pile of gray hair sometimes unaccountably died a stark black. She wore an interchangeable wardrobe of flowered housedresses. At that time, legions of housewives spent their days in a “housedress,” an article of clothing which for some ineffable reason was considered better than wearing, say, pants and a shirt, but still not good enough to wear farther than your front porch or your backyard. Inside, you could meet the Pope in your housedress. Outside, you might as well be naked in a housedress. Nonna was one of the few who rebelliously wore housedresses beyond sight of their houses. Winters, Nonna topped off the flowered housedress with a coat that was nominally fake brown fur, but resembled medium pile wall-to-wall carpeting with buttons. Richie said Nonna sent the coat to Magikist with Nonno in the spring to get cleaned with the rest of Chicago’s dirty rugs. It was true.

Spring, summer, fall and winter, Nonna carried her genuine alligator clutch purse from Cuba, a Christmas present from Nonno in 1955.

The youthful reptile that gave its life for Nonna’s purse stared eternally at the world from the cover flap, its entire skull mounted there diagonally as absolute proof of authenticity. When Steve thought of the purse as an adult, he usually saw the alligator peering through the crook of Nonna’s elbow, pressed firmly into her flowered housedress against her ample side.

If you opened the purse’s front flap and laid the whole thing down flat, the alligator’s entire flayed pelt sprawled before you. The hind legs bent at the knee, stitched in place with strong brown thread, as if to prevent the animal from leaping at passersby. Steve wondered why the alligator’s tail wasn’t there too. “Because he doesn’t need it anymore,” said Richie.

Young Steve was careful to keep his fingers away from the alligator’s mouth whenever he unsnapped the cover to rummage through Nonna’s purse. He might be looking for something, but mostly it was just something to do. Nonna’s alligator carried her wallet, keys, whole and half-used packs of Life Savers, lipsticks, her many travel packs of Kleenex, and an encyclopedic collection of free promotional plastic rain hats folded into vinyl pouches advertising every Roseland business, from Tony Aurelio Insurance to Doty-Panozzo Funeral Home; through Gately’s People Store, the Home Store, Jays Potato Chips and Jensen’s Movers; on to Panetti’s grocery, Pesavento’s Restaurant and Pullman Wine & Liquors; swinging through Root Brothers hardware and building supplies to Sherwin-Williams; and ending finally with Ziggy’s golf range, where Nono also worked on weekends, officially named “Sheldon Heights Golf Range” and featuring “Ziegfield A. Troy, Golf Professional.”

Tony Aurelio Insurance, 10956 S. Michigan; the Home Store, 118th and Michigan; Jay’s Potato Chips, 825 E. 99th; Jensen’s Movers, 11636 S. Halsted; Doty-Panozzo Funeral Home, 214-218 E. 115th; Panetti’s grocery (11529 S. Michigan); Pesavento’s Restaurant, 11500 Front Street; Pullman Wine & Liquors, 305 E. 115th; Root Brothers, 103rd and Michigan; Sherwin-Williams, covering 104 acres at 115th and Cottage Grove; Ziggy’s golf range, 115th and Halsted.

Nonna also collected any other brand of plastic rain hat handed out free, and free promotional plastic rain hats were nearly as common as promotional matchbooks. She was partial to the Wonder Bread rain hat handed out one year in the Home Store’s basement grocery store, even though she would never have considered eating the stuff. Nonna didn’t eat store-bought bread for the first 15 years of her life, and didn’t believe Wonder Bread was even made out of the same ingredients as the loaves she and her mother baked in Kansas.

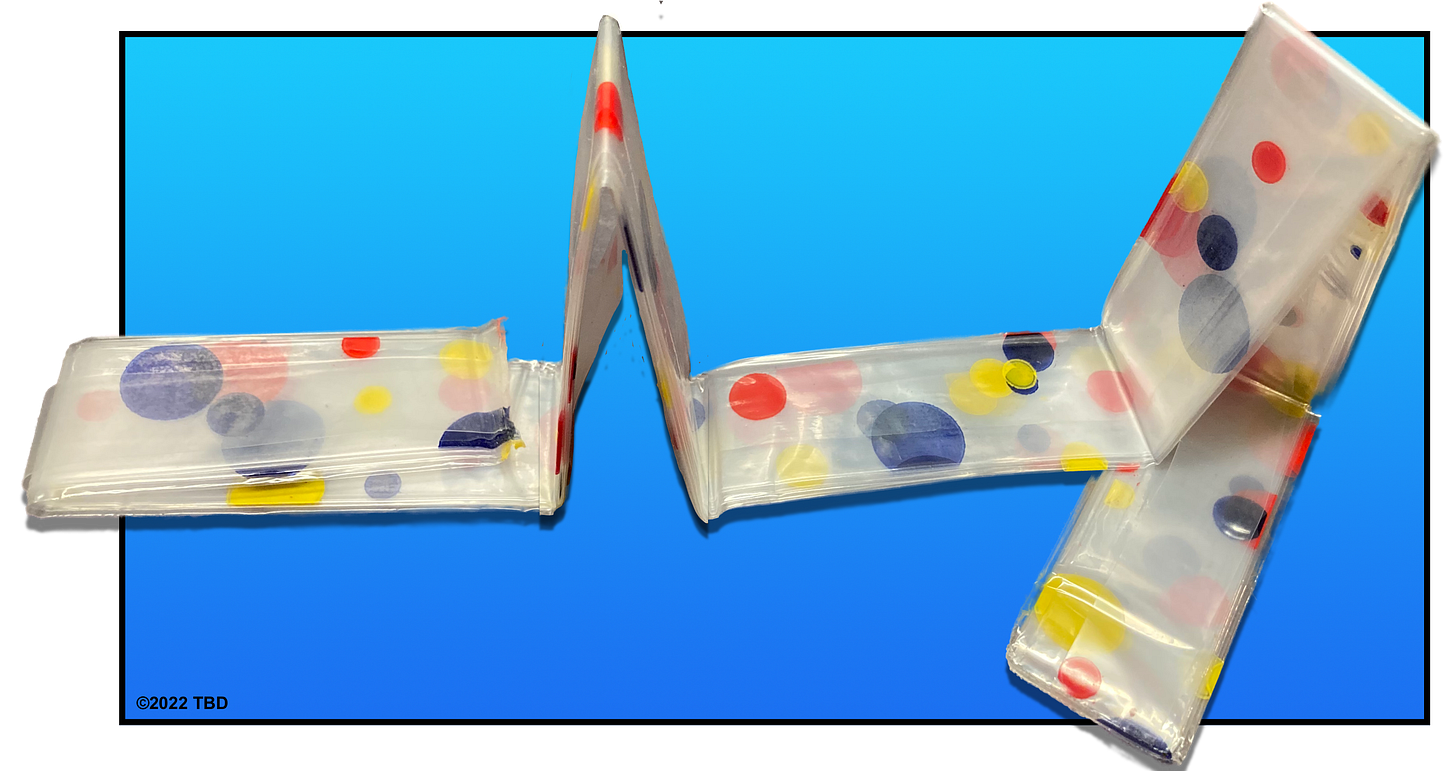

Oh wait. You probably don’t even know what a plastic rain hat looks like. I’ve seen them out of their pouches. They’re more like plastic scarves than hats, with long plastic ribbons on either end to tie under your chin. When did adult women stop walking around with their heads wrapped in plastic like a dessert at a bake sale whenever it rained? Did they all just agree to stop one day? I asked Gil, and for once, he was stumped.

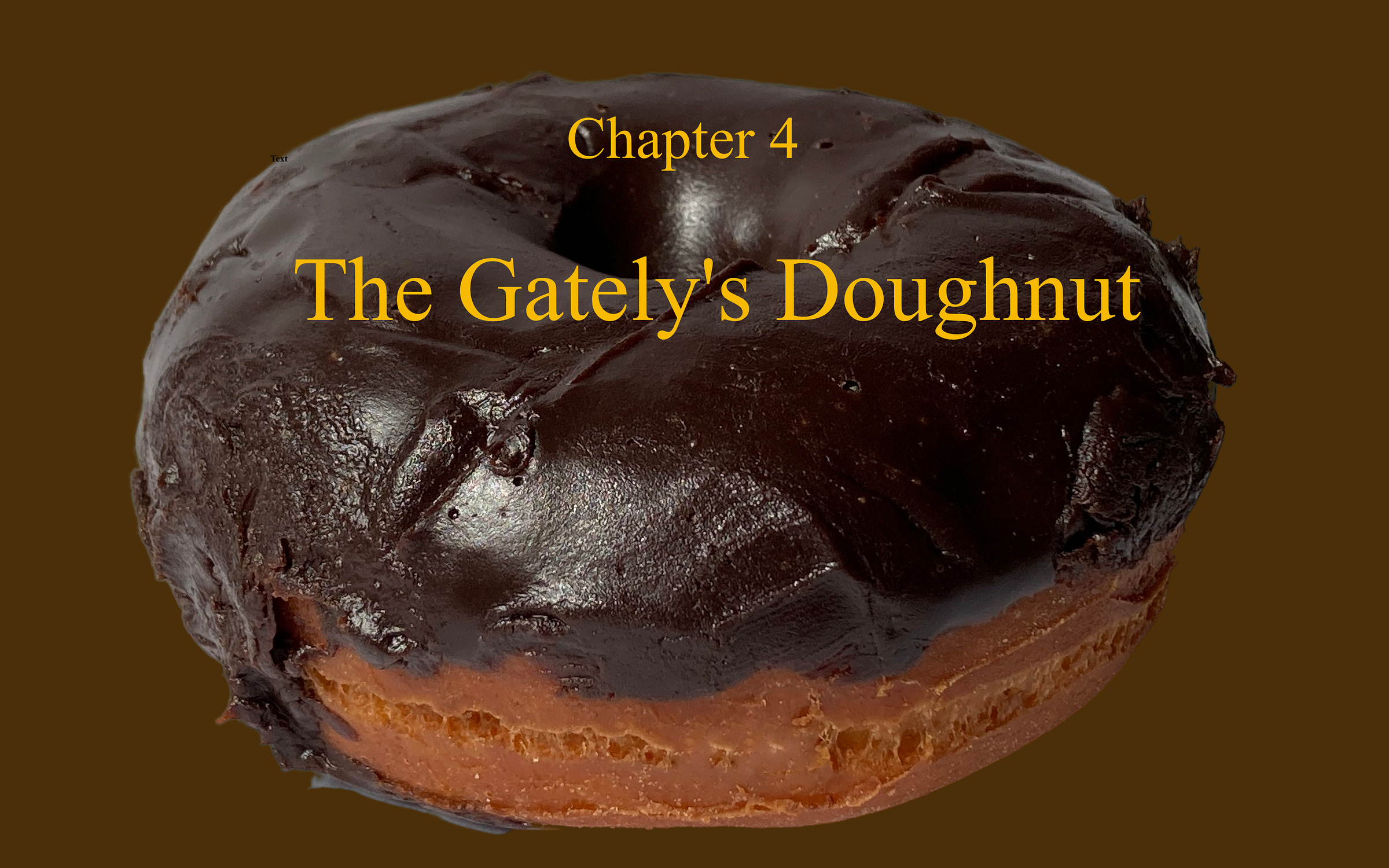

Here’s Nonna’s Wonder Bread plastic rain hat, inside its red vinyl pouch:

Here’s the Wonder Bread rain hat itself, neatly folded in accordion form like all rain hats to fit snugly inside their vinyl pouches.

And here’s what Nonna’s head looked like inside her Wonder Bread rain hat. Just imagine her wild hair trapped inside that wrapper instead of the Wonder Bread, either grey, stark black, or both if her roots were growing out.

Nonna’s plastic rain hat collection was only slightly larger than the average woman’s. If you were to guess the mortal dangers facing humanity in Steve’s childhood based entirely on promotional products, you’d have to go with the chance of women’s hair getting wet from natural precipitation as the most pressing global concern of the day.

Nonna’s alligator glared at the world from tiny glass eyes that seemed to change with the humidity, the paint fumes from the Sherwin-Williams paint factory, or Nonna’s moods. The eyes shifted silently from a sickly yellow to a menacing amber and all points in between, stopping on the most dire occasions at a flat neutral darkness that merged with the round black merciless pupil.

Nonna had expected that her purse would double as a toy for young grandchildren, but it was a rare youngster who didn’t find the alligator threatening rather than playful. Young Steve sometimes read out loud to the alligator, but he was careful to prop it up to listen at a safe distance.

“Why won’t you kids play with him?” Nonna wondered.

“Because he’s evil,” said Richie.

“He’s not evil!” yelled Nonna. “He’s just misunderstood!”

Steve never understood why carrying a dead animal around was not, itself, bad luck.

“Bad luck for him, not for me!” Nonna would laugh, patting the alligator on its rough scaly head.

So you see now that Nonna’s bad luck signs were completely unpredictable. And the most unpredictable bad luck sign—most unpredictable for Steve, at least—came one day when Nonna and Steve were waiting for a bus on the Ave, as everyone called Roseland’s bustling commercial district on Michigan Avenue.

ii. What Happened on the Ave

The busiest part of the Ave was 111th to 115th, but many would measure the Ave from about 103rd through at least the Home Store at 118th. The Ave was a Chicago neighborhood edition of the Bedford Falls Main Street in “It’s A Wonderful Life,” stuffed with neighborhood shops and anchored by Gately’s Peoples Store at 112th, a miniature version of Marshall Field’s majestic department store on State Street in the far away land of the Loop. Roselanders seldom bothered with Marshall Field’s and the Loop. What did anyone need that you couldn’t get on the Ave? Besides, it was a pretty long trip downtown on the IC, by bus, or driving on Chicago’s most dangerous expressway, the Dan Ryan.

One morning in late 1967, just before Thanksgiving, Steve and Nonna stood at the bus stop on the Ave after a trip to Gately’s. This is not the day Steve encountered something that looked like chewed-up gum which would haunt him for decades, but it was a seminal day in Steve’s life nonetheless, and it will come up again.

Nonna raged happily at the Christmas decorations already looped across Gately’s storefront and hanging from the Ave’s streetlamps. “It’s too goddam early!” she yelled. “It isn’t even Thanksgiving, goddammit!” She’d been in a great mood ever since the White Sox lost a four-way race for the American League pennant in late September, insuring the Pope would not come to Chicago, which is another story for later.

Here is Gately’s and the Ave in the 1950s, a tad earlier than the day we’re on right now. But this picture is a close-up of Gately’s, and more how Steve remembers 1967, but with buses instead of streetcars:

A pleasantly plump young white woman sashayed up to the bus stop and stood right next to five-year-old Steve. In those days, a healthy, robust Marilyn Monroe was still a beauty icon; I mean the sort of Marilyn Monroe you see in “Some Like It Hot,” busting out of her dress in every direction. This woman was no Marilyn Monroe, but she had won the title of Miss Roseland a couple of years earlier. She had every reason to consider herself a good catch.

Steve noticed the pleasantly plump young woman because she was holding a package of Kent King-Size cigarettes, but she was making no move to take out a cigarette and light it up.

This was strange. In 1967, adults were forever reaching in a pocket or purse to pull out a pack of cigarettes; expertly sliding one out; and lighting it up with a cigarette lighter they’d pulled from somewhere else. They were all so dexterous when it came to cigarettes, the simple act of smoking was like a magic trick. Grown-ups didn’t just stand around holding a pack of cigarettes without smoking. That would be like a kid standing around holding a Hershey bar and never eating it.As Steve studied this anomaly of nature, the young woman flipped open the top of her pack of King-Size Kent cigarettes. What was inside? Not two rows of perfect white cylinders stuffed with tobacco, but two round dials with delicate tiny teeth dotting the circumferences, like gears in a machine. The young woman fiddled with the righthand gear.

Now Steve caught sight of a slender, almost invisible white cord snaking up from the Kent cigarette pack and disappearing into the hard hair-sprayed blonde sphere around the young woman’s head. Ahhh. This was not a pack of Kent King-Size cigarettes, this was a pocket transistor radio made in the likeness of Kent King-Size cigarettes! Long before receivers were implanted in babies’ skulls prenatally, before iPhones or even Walkmen, pocket transistor radios ruled. If you wanted to walk around listening to music, or anything, your only real option was a pocket transistor radio. Pocket transistors typically only provided an AM dial, and they came with a single earphone—no impulses delivered directly to your brain internally, no stereophonic headphones or earbuds.

Steve guessed correctly that the young woman was listening to the end of Wally Phillips’ morning show on WGN, 720 on the AM dial, and as so often happened with radios, the reception had drifted and she needed to adjust the tuning dial.

Nonna took one look at the pleasantly plump young woman and shoved Steve so hard he fell down, dropping the fresh chocolate-frosted doughnut he’d just gotten at Gately’s for breakfast.

Steve’s chocolate-frosted Gately’s doughnut landed on its side and wobbled.

Nonna had already consumed her own breakfast--a cupcake, since she considered doughnuts too savory for breakfast. Nonna ate dessert for breakfast every day. “You never know what the hell’s gonna happen by dinner time, I’m not gonna miss dessert!” she yelled.

Though she herself had no use for doughnuts so early in the day, Nonna had let Steve watch the doughnut machine in Gately’s basement for nearly a half hour that morning. The doughnut machine mesmerized him: the raw dough emerged magically from a hole, dropped into an oval-shaped well of oil, sizzled, got flipped by a mechanized basket and finally tossed onto a tray, all without the help of human hands. A doughnut counter lady sprinkled the finished doughnuts with powdered sugar or dipped them in chocolate frosting.

Steve considered Gately’s doughnut machine the Roseland equivalent of an exhibit at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, where the Mold-O-Rama machine created white or green plastic busts of Abraham Lincoln right before your eyes for 35 cents. The Bertolucci’s had two Lincolns on a shelf in the front room, one white and one green. As a rule, Roseland kids went to museums only on school field trips, which occurred approximately almost never. Thus five-year-old Steve had never been to the Museum of Science of Industry, and could only listen greedily to his older brothers’ field trip tales, in which the Mold-O-Rama machine was a major exhibit on par with the German submarine from World War II.

So Gately’s basement doughnut machine was the Museum of Science of Industry for Steve, on the Ave at 112th. Likewise, he considered the Home Store, at the southern end of the Ave at 118th, to be his Field Museum of Natural History. Steve’s brothers had told him all about the Field Museum’s landscape dioramas with the taxidermied animals behind glass walls. The Home Store, he was sure, was just as good. The Home Store’s basement was a grocery store, and at that time the shelving in one aisle was topped by a promotional display of Chuck Wagon dog food’s red-and-white checked covered wagon drawn by horses. You could practically hear the tiny cowboy sitting in the wagon’s box yelling “Giddap!” at the brown horses.

But back to that doughnut.

Steve was still holding a whole Gately’s doughnut because just as he was about to take his first bite, the pleasantly plump young woman had walked up with that package of Kent King-Size cigarettes that turned out to be a radio. Instead of tearing into his doughnut, Steve had wondered at a grown-up holding a pack of cigarettes without taking one out to smoke.

The chocolate frosting on a Gately’s doughnut was the same color as Nonna’s fake fur coat, which she was wearing that day since Thanksgiving was reliably cold in Chicago back then. The chocolate frosting was darker than Nonna’s genuine Cuban alligator clutch purse, and the tiny alligator skull mounted on the purse’s front flap, but the two shades would have appeared on the same Sherwin-William gradient paint chip card. The alligator’s baleful yellow eyes now looked down at Steve on the ground, and those eyes glittered pitilessly.

When Nonna shoved Steve, his prized 1967 Roseland All-Stars Little League baseball cap flew off his head and onto the ground along with him and the chocolate-frosted Gately’s doughnut.

The 1967 Roseland All-Stars Little League cap--red with a big white “R” on the crown and too big for Steve’s head--belonged to Brownie, his third-oldest brother. Brownie had played catcher that summer as Roseland became the U.S. championship team, barreling all the way to the final game of the Little League World Series before losing the world title 4-1 in a heartbreaker to West Toyko. Some Einstein had not yet invented a method to make baseball hats truly adjustable, so Brownie’s hat was just the right size for Brownie’s 12-year-old head, but many sizes too large for Steve’s five-year-old head. The tiny bit of elastic sewn into the back of the hat helped not at all. Still, soft-hearted Brownie let his youngest brother wear the valuable cap because he and Steve were soul mates on an elemental level: both boys were in constant thrall to their unquenchable desire for chocolate.

You remember Brownie, right? He was another of the three brothers who had a Black Cow during that “Columbo” episode in 1971—the one who threw the Sealtest ice cream for a long pass that was really very short.

On this day just before Thanksgiving, mere weeks since the Little League World Series, Steve wore the cap constantly—to bed, to the bathtub, to anything. “What are you, Jewish?” Nonna would say when she saw Steve in the house with the All-Star cap on his head. He had no idea what she meant, and since she didn’t wait for an answer, he let it go.

The world stood still for a panicked moment as Steve sat on the cold sidewalk, the freezing cement searing through his brown corduroy pants, and beheld with horror the simultaneous endangerment of both his chocolate-frosted Gately’s doughnut and his 1967 Roseland All-Stars Little League cap.

The doughnut cost five cents; Nonna would never agree to buy another one that day. “Whaddayathink, I’m made-a-money?” he knew she’d yell. “We lost all our money when that lousy bank closed!”

The 1967 Roseland All-Stars were the first Chicago team to ever reach the final match of the Little League World Series; the cap was irreplaceable.

Steve faced a terrible choice for one so young.

The late November wind lofted the red 1967 Roseland All-Stars Little League cap and sent it slowly pinwheeling toward the street as a roaring CTA bus lumbered toward the bus stop.

The chocolate-frosted Gately’s doughnut still wobbled on its side like a slowing top, its momentum grinding to a halt with no hint of which way the doughnut would fall: frosting-side up, or frosting-side down.

No baseball fan, Nonna thought only of the five-cent doughnut.

“Pick up the doughnut!” yelled Nonna. “Kiss it up to God!”

Though yelling was Nonna’s normal tone of voice, Steve understood in this context that Nonna also meant to communicate urgency.

The minute Nonna commanded Steve to save the doughnut, he instantly knew what he really wanted to do was save the hat. And somewhere farther back in the recesses of his mind, he dimly remembered he’d faced a similar choice before. He’d had a similar moment of absolute clarity, and failed to act on it. Now, with the fate of his doughnut hanging in the balance, Steve desperately yearned to act on this shining, startling clarity. But it was impossible. A higher force was in charge: Nonna was a grown up in 1967, and she had told him what to do.

Faced with a direct order from an adult, Steve instantly obeyed and saved the doughnut first, snatching it from the ground microseconds after it landed.

He touched the doughnut to his puckered lips before lifting it toward the sky and God for a final ablution. He wholeheartedly believed God would eradicate whatever germs the unfortunate doughnut had picked up during its brief sojourn on the sidewalk.

As Steve raised the doughnut high above his head into the grey November sky, he saw the red 1967 Roseland All-Stars Little League cap roll into the street and under the front wheels of the dirty, wheezing CTA bus pulling into the bus stop.

The pleasantly plump young lady moved toward the bus door as it groaned open. Nonna leaned down to Steve’s ear. Her crooked glasses tilted another half inch off-kilter. Sometimes the glasses slanted so far, Nonna looked like a Picasso.

“It’s bad luck to touch a fat lady’s skirt!” she hissed, adjusting her fake fur coat as if it were a valuable mink. “None of my charms will work on that,” she added, holding up her wrist and jangling the heavy charm bracelet in Steve’s face. The big round dog-on-a-leash charm clipped him in the right eye.

This information was both new and confusing. First, Steve had never heard Nonna’s voice lower than a yell. Second, he’d never heard anything about fat ladies being bad luck. Third, that lady was fat? Fourth, Nonna herself carried a fair amount of spare flesh.

As they stood there at 112th and the Ave, Steve could see Nonna’s physique was barely altered by her recent 1967 summer of intense fear when Richie had been right about how to read baseball standings, which showed the White Sox might make it to the World Series, which meant the Pope might come to Chicago. Again, this is a story for later—see Chapter Six: St. Anthony’s Crucifix. The point is, many hot mornings, Nonna had barely eaten her dessert for breakfast. Yet she still looked like she’d had second and third helpings. Nonna always angrily denied being fat, pointing to the skinny legs protruding from the hem of her flowery housedress. Nonna counted anything above her thighs as part of her expansive bustline, and in Nonna’s world big breasts were never fat, they were always desirable, among the most valuable assets anyone could possess.

Steve didn’t have time to reflect on this unexpected new source of bad luck, because he had to save the Little League cap.

He darted over the curb and plucked the cap from the street, now red with a sooty bus wheel track striped across the center of the crown.

Steve jumped back on the sidewalk and looked down at his hands. In his right, the wholly undamaged chocolate-frosted Gately’s doughnut. In his left, the formerly pristine red 1967 Roseland All-Stars Little League cap, its proud white “R” splattered into a dispiriting grey.

There would be more Gately’s doughnuts in the future--not that day, but soon. There would be no more 1967 Roseland All-Stars Little League caps. Brownie would kill him. Literally kill him. Steve had made the wrong choice, and he could never go back.

Poor Steve. Even as he stared at the ruined Roseland All-Stars Little League cap, his mind struggled to recall that past calamity, his first lesson in the perils of free will and wrong choices. He had learned from that previous mistake, he had tried to act on his moment of clarity, but he was powerless against a societal authority figure. He was only five, and in 1967. I will tell you about Steve’s first run-in with free will and a mind-boggling choice, in Chapter 10: Jack Cassero. It had happened almost exactly one year before the Gately’s doughnut debacle, during the International Livestock Show at the Ampitheater.

Before Steve could absorb this new reality in which Brownie’s All-Stars cap was ruined and he was the one who ruined it, Nonna propelled him up the bus steps and into a seat. At that point riding the bus was like getting a piggyback ride from the guy who just murdered your mother. After a few blocks, Steve licked the chocolate frosting. He tasted nothing.

iii. The Little House

One week after Nonna knocked Steve over at the bus stop, Steve was still alive.

Brownie had not killed him over the Roseland All-Stars hat. “What are you talking about,” Brownie said when his little brother started sniveling about the smudged black stripe across the red crown. “It’s a baseball hat. It’s supposed to get dirty.”

Aunt Mae was in town for Thanksgiving from Frontenac, the little coal-mining town in Kansas where Nonna’s family had first settled in the new country. Nonna had freshly dyed her hair black for Aunt Mae’s visit. She was still leaving coal-black smudges on towels and furniture, driving Steve’s mom wild. Already, Nonno had taken one of the Bertolucci’s two front room upholstered chairs to work in his Magikist van to remove evidence of Nonna’s latest makeover.

Aunt Mae knocked on the back door that morning just as Nonna finished harvesting coupons from the previous day’s Daily News at the Bertolucci’s kitchen table and started work on the Chicago’s American she’d brought with her. The Bertolucci’s got the Daily News, but Nonna was strictly a Hearst reader—which means she wanted sex, she wanted sensation, she wanted blood-and-guts crime. The Chicago Tribune had bought the Herald-Examiner from Hearst about ten years earlier, renamed it the American, and toned it down considerably. That infuriated Nonna. She blamed Colonel McCormick even though he was dead when his paper bought her paper. But Nonna had nowhere else to turn. The other papers were respectable. The worst thing you’d see in the Daily News was an AP or UPI picture of a pretty girl tangentially related to a news topic.

Nonna was listening to Mrs. Bertolucci’s kitchen radio, a heavy sky blue Westinghouse table model from the old vacuum tube technology days, before the tiny, light transistor was invented. Mrs. Bertolucci loved this radio, a wedding present from her childhood best friend, Jackie Siciliano, nee Covelli, who now lived next door. Mrs. Bertolucci kept the sky blue radio where it would always be close to her, on the kitchen counter near the phone hanging on the dinette wall. The sky blue Westinghouse should have had two round dials on either side, instead of the two sticks of metal you see sticking out in this picture.

One knob turned the sky blue radio on and off and adjusted the volume; the other moved a thin red line across the radio band to tune in different stations. Frank and Rocco had pulled off the knobs one day when they were playing Checkers and needed to replace some lost pieces. Then, of course, they lost the knobs. The radio generally stayed on now because it was so hard to turn off. It was always tuned to WGN anyway, so losing the tuning knob was less of an issue.

Wally Phillips had just played the second half of Ellery Queen’s Minute Mystery, the solution to the crime Ellery Queen was investigating that day. It turned out the guy picking blackberries was a murderer. Ellery Queen figured it out from a tiny detail, like Columbo.

When Aunt Mae rapped on the back door, Nonna yelled for her to come in and reached for the counter to snap off the radio. As always, Nonna had a hard time gripping the slippery metal stick where a dial should have been, so she was swearing when Aunt Mae skipped up the back steps and into the kitchen. “Goddammit that radio’s too loud!” started Nonna’s string of curses. Nonna was hard of hearing, yet anyone else’s radio or television was “too goddam loud!” in her estimation. That included anything playing on a radio she couldn’t turn off because Frank and Rocco had lost the knobs.

Aunt Mae was considered voluptuous in Kansas, and she arrived in a good mood because two different old Italian men had whistled at her as she walked over to the Bertolucci’s. She was pleased to hear her sister in fine spirits, judging by the lilt of Nonna’s curses regarding Frank, Rocco, and the radio. Aunt Mae let Nonna finish her profane soliloquy while she took off her plastic rain hat and attempted to fold it back into an accordion. It wasn’t raining, but Aunt Mae was one of those women who used plastic rain hats as more of a windbreaker for her head.

Nonna gave up trying to turn off the radio and wrapped Aunt Mae in a bear hug.

Steve instantly shoved Nonna away from Aunt Mae.

Nonna stumbled into the table in the cramped dinette. About two inches of the table corner disappeared into a dent of Nonna’s flowery housedress. She shrieked.

“It’s bad luck, Nonna!” little Steve bleated. “She’s wearing a skirt!”

It was not the last time Steve would be confused by shifting cultural standards for the female form. Voluptuous? Fat? Who could keep up?

Nonna clobbered him with the nearest wooden kitchen spoon.

“Are you crazy?” she yelled. “That’s my sister!”

After Aunt Mae left, Nonna found Steve sitting on his bed, the bottom bunk against the north wall in the bedroom off the kitchen, reading “The Little House” by Virginia Lee Burton to his friend Smarty Jones and the alligator purse, propped up at a safe distance on the far side of the mattress. The tiny alligator skull’s yellow eyes glittered with apparent interest in the story.

Remember, books were usually scarce in working class neighborhoods beyond the Bible, and that included children’s books. Books weren’t all that cheap. Even at the Bertolucci’s there were only a handful, though Mrs. Bertolucci was a bona fide neighborhood intellectual thanks to attending almost a full year at St. Xavier’s, a small Catholic college on the Southwest Side. Every book at the Bertolucci’s, including the Bible, bore the pencil scars of a run-in with Tony/Guido, Steve’s second-oldest brother. Tony drew tiny stick figures on the bottom corner of each page to create flipbooks. When you riffled the pages of “The Little House” backward, for instance, two stick figures with Roseland Little League hats played catch at the bottom of the left hand pages. If you riffled the pages front to back, a Roseland Little League stick figure swung a bat on the lower right hand pages and hit a home run.

Besides “The Little House,” Steve could choose from Virginia Lee Burton’s more well known “Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel;” Maurice Sendak’s “Where The Wild Things Are;” Elsa Holmelund Minarik’s “Little Bear’s Visit;” and Arnold Lobel’s “Frog and Toad Are Friends.” To go with the handful of books, the Bertolucci’s had an infinite supply of bookmarks, one of many uses for the Sherwin-Williams paint chip cards that fell off Mr. Bertolucci like loose colorful feathers everywhere he went.

Steve picked “The Little House” most often. Smarty Jones had to go along with Steve’s book choices, since he couldn’t read. Smarty was sensitive about that.

“No, I can’t read, so what?” Smarty said once when they were sitting on the front porch reading “Where The Wild Things Are” and Tony/Guido came home from school and said Smarty should read to Steve sometimes.

“You’re so smart,” sneered Smarty, “you do it.”

You remember Tony. He was also one of the three brothers who had a Black Cow in 1971 during that “Columbo” episode where Beth kills her annoying brother. Tony was the one who caught the carton of Sealtest ice cream and yelled, “I’m hijacking this ice cream to Cuba!” The others kept calling Tony “Guido” over Mrs. Bertolucci’s strenuous objections, because that was his nickname.

“OK, I will,” Tony had told Smarty that day on the porch, and he took “Where The Wild Things Are” from Steve and read it to both of them. Three Sherwin-Williams paint chip card bookmarks fell out of the book as it traveled from Steve to Tony.

When Tony finished reading, he riffled the pages and watched the Roseland Little League stick figure hit a home run. “I should’ve made him hijack a plane,” he said. “Why didn’t I do that? I guess they weren’t hijacking planes so much, back when I read this. I wonder why.”

He closed the book and looked thoughtfully at Steve. “I never get how Max is gone for a whole year with the wild things, but his dinner’s still hot when he gets back,” he said.

“See, you’re not so smart,” snickered Smarty. “He didn’t really go anywhere, he imagined it! That’s why it’s still hot!”

“Whaddaya think Stevie, did Max really go somewhere for a year or not?” Tony/Guido asked.

“Yes,” Steve said instantly.

“How?” squawked Smarty.

“Magic,” said Steve. “And it was magic that his dinner was still hot, too.”

“I wish I could do that,” said Tony/Guido, riffling the book pages to watch his old pencil stick figures play catch. “Anyway, it’d make a good ‘Twilight Zone.’”

On the day of Aunt Mae’s visit, Steve had picked up “The Little House” over Smarty’s sharp objections just before Nonna found them.

“Aunt Mae left, here!” yelled Nonna. Through the open space between the upper and lower bunks, Steve could just see the bulging middle of Nonna’s flowery housedress. Now a hand came through the opening.

Nonna gave Steve a piece of the gustoli she’d just made. Gustoli was a delicacy even better than a Gately’s doughnut--a thin bow-shaped piece of pastry, deep-fried and doused in powdered sugar.

“I’m sorry, you lousy son-of-a-bitch,” she yelled, tenderly patting Steve’s head, which unfortunately resulted in Steve’s head getting hit repeatedly by several heavy charms on her bracelet. “You were just looking out for your old Nonna. But it’s OK, Aunt Mae isn’t bad luck.”

“Thanks Nonna,” grinned Steve, accustomed to Nonna’s abrupt reversals. “Can Smarty have a piece too?”

Nonna winked and held out another glistening piece of gustoli. “Sure, I brought one for Smarty,” she yelled. “Even though that lousy son-of-a-bitch never says thank you!”

She was right. Smarty just stared and said nothing.

“And turn off that goddam radio!” she yelled on her way out the door.

“What radio?” said Steve.

“I thought I heard a radio!” she yelled.

Steve and Smarty went back to “The Little House,” happily munching the gustoli. Steve was using a Sherwin-Williams bookmark of orange paint chip samples, because the darkest orange on it matched the autumn leaves falling around the Little House during the apple harvest. His friend next door, Amy Zoccoco, had shown him how the Sherwin-Williams paint chip cards could be matched with almost anything.

The eponymous Little House was just big enough for a friendly front door with a rounded top and a large window on either side. The door and windows together constituted a contented, happy face as recognizable as the real face drawn on the smiling, winking and yawning sun as it rose at the bottom of one left hand page, gamboled over the Little House in a high golden arc, and set at the bottom of the right hand page.

The story was as engrained in Steve’s young brain as the oldest fairy tale:

The Little House is built once upon a time in the country, on a hill covered with white daisies and apple trees all around. She watches the seasons go by, and the moon and stars at night.

The Little House can see the city’s lights in the distance. She is curious about the city and wonders “what it would be like to live there.” Steve had another Sherwin-Williams bookmark of yellows for “The Little House” selected by Amy that perfectly matched the city lights.

Then a steam shovel rips through the hill covered with daisies and knocks down the apple trees for a paved road. Cars replace the horses and wagons. More houses get built all over. The other houses turn into “apartment houses and tenement houses,” all crowded around the Little House. An elevated train line is built down the middle of the street, right in front of the Little House. Skyscrapers go up on both sides of the Little House, skyscrapers so tall the upper stories are ringed by clouds. A subway gets built underneath.

“Now the Little House only saw the sun at noon and didn’t see the moon or stars at night at all because the lights of the city were too bright,” Steve read to Smarty.

By this time, the Little House’s two big window eyes are broken. Her friendly rounded front door nose/mouth is cruelly nailed shut with criss-crossed wooden boards. The Little House looks like a bunkhouse in a prisoner-of-war camp. She looks worse, in fact, than Steve McQueen’s prisoner-of-war bunkhouse in “The Great Escape.”

Much as they loved the book, Steve and Smarty also found “The Little House” disturbing, because the Little House hated the city. To Steve and Smarty, the book’s drawings of the city were beautiful, with the colorful cars and trollies and L train; the puffy white clouds ringing the tops of the skyscrapers; the glowing yellow lights at night. That was how Steve and Smarty thought of Chicago’s Loop—pretty and exciting, a rare and amazing destination.

But that was not how the Little House thought of her own unnamed city. The book said the Little House couldn’t tell anymore when Spring came, or Summer or Fall or Winter: “It all seemed about the same.”

Steve and Smarty knew this wasn’t true at all in Chicago. You sure knew the difference between summer and winter in Chicago, in Roseland or the Loop. They wondered what they were missing. Was Chicago as ugly and horrible as the Little House’s city, but they somehow could not see it? All they knew for sure was that they could spend a good hour on a slow day matching Sherwin-Williams paint chip sample cards with the daisies, apples, and sun in the Little House’s country, or the buildings, buses, trains and street lamps in the city. It was something to do.

Finally, the great-granddaughter of the man who built the Little House finds her, jacks her up off her foundation and moves her to the country, where the family lives in her again. The Little House is happy: “Once again she was lived in and taken care of.”

Steve and Smarty understood this was supposed to be a happy ending, so they tried to be happy for the Little House. But it bothered them that the Little House would “never again…be curious about the city”. It was hard not to take that personally.

On this 1967 day just before Thanksgiving, Steve nibbled the gustoli and turned to the last page, where Tony’s stick figure finished hitting a home run. Just then, Tony’s head popped in the door.

“Hey, did Nonna give you any gustoli?” Tony whispered.

“Yeah,” said Steve. “Why’re you whispering?”

“She’s mad at me, shhh. Hey Smarty, lemme have a piece.”

“Hey waitaminute—“ squealed Smarty.

“Oh you can’t finish it anyway,” hissed Tony, closing the door and sitting down on the bed. “What’s that, ‘The Little House’? I remember this. I usedta read this all the time before we had MAD. You don’t read MAD yet?” Tony glanced over at a MAD on Rocco’s bed. The cover featured gap-toothed Alfred E. Neuman in four darker incarnations besides his usual peachy-pink self—in a straw hat as some sort of Asian peasant; as an American Indian with headband and feathers; in a turban as perhaps a Sikh; and as a generic African. “SPECIAL RACIAL ISSUE” blared the headline. He feinted toward Rocco’s bed, then seemed to think better of it and headed to Steve’s bunk.

“Lemme see,” said Tony, taking the book and flipping back to the page where the Little House is nestled between the two skyscrapers with rings of puffy white clouds around the upper stories. “Here’s what I never get,” he said, pointing at the Little House dwarfed by soaring skyscrapers. “Now why doesn’t the great-granddaughter just leave the house right there, fix it up and move in? You know how valuable that land would be now that it’s downtown? She’d be a millionaire. Her husband could get a job downtown and just walk to work.”

It didn’t occur to Tony, in 1967, that the great-granddaughter could get a job and walk to work. Or that she might not be married. Or that since the land would be so valuable, she would never be able to afford the taxes and would have to sell the house if she didn’t move it someplace cheaper.

“The whole thing is nonsense,” said Gil when we discussed it one day. “If the family abandoned the house, which they clearly did, they weren’t paying real estate taxes on it. Look at it, all boarded up. That didn’t happen overnight. That house would’ve been seized by Cook County and auctioned off. Really, one of the companies that own those skyscrapers next door would’ve gotten their expensive lawyers to get the lot from the city for one of those $1 leases for a hundred years.”

“It’s a children’s book,” I said. He shrugged and walked away.

Back to Tony’s analysis of “The Little House”:

“Or you could get on the L, right there, to go to work,” Tony added, pointing at the cute little green L train running past the Little House.

Steve stared at the picture. Why hadn’t he seen it before? “Yeahhhhh,” he said slowly. “Wouldn’t the Little House be happy as long as the family lived in it and took care of it again? No matter if it was in the city or the country?”

“It’s a house, why not?” scoffed Tony. “What’s it gonna do in the country, go hunting?”

Tony could be as sarcastic as Richie sometimes. In a classic nature versus nurture mystery, this may have been the result of growing up in Richie’s sarcastic shadow. We’ll never know.

“What’s so great about stars anyway?” said Smarty, staring out the window. “I like streetlamps.”

“Then maybe you should marry one,” said Tony.

“I’m never gettin’ married!” squawked Smarty.

“That’s good ‘cause I don’t think even a streetlamp would marry you, you’re so short!” laughed Tony.

“C’mon you guys,” said Steve. Tony and Smarty could barely talk for two minutes without bickering.

“He started it,” Smarty sulked.

“Of course I started it,” Tony smirked at Smarty as he handed the book back to Steve and peeked out the door for Nonna before starting out. “You can’t start anything, you’re such a dummy!”

“Why’s Nonna mad at you?” Steve whispered as Tony slipped out.

“Rod Serling got in the front hall for a minute when we came in to get some gustoli,” he hissed, and then he was gone.

Rod Serling? Don’t worry, it will make sense later on. I can’t tell you everything at once.

At this point Steve bumped the brim of the Roseland Little League All-Stars cap against the top bunk bed mattress just above his head, since of course he was still wearing it. He took it off and he and Smarty regarded the awful black stripe across the now dirty red crown. He still couldn’t quite remember that earlier incident involving free will and a difficult choice. It would come to him later, he knew, when he least expected it. Regardless, Steve was positive he had made the wrong choice when he obeyed Nonna and snatched the doughnut. Then again, he knew losing a Gately’s doughnut would not have been an inconsequential event either.

“Maybe sometimes nothing is right,” Steve told Smarty.

Smarty just looked at him like he was crazy.

Then Steve and Smarty started the book over again. Somehow it always felt like if they read “The Little House” just once more, this time the house would like the pretty city lights and the cute L train and the puffy clouds ringed around the tops of the skyscrapers. But no. The house never changed its mind. At least Tony’s stick figures always caught a ball or hit a home run.

Steve was drawn to “The Little House” for its beautiful pictures and simple prose. He was also drawn by the startling idea that a city grew and evolved, though he didn’t understand the source of his attraction in those terms. He was shocked when Mrs. Bertolucci pointed out that “The Little House” was just like Roseland. Roseland, she explained, had started out as a Dutch farm community in the countryside outside Chicago.

What? Steve saw Roseland and Chicago as eternal and unchanging as Lake Michigan. Technically, even at five, he knew America used to be inhabited only by Native Americans, then called simply “Indians.” You couldn’t turn on the TV and not see western movies that made this point quite clearly. But his young brain had a parallel track in which Chicago had somehow always been there too, the same way he knew and did not know that Santa Claus wasn’t real.

No, said his mom. Once upon a time, she said, Roseland was open country. One day, a few settlers started farms here and there. Before long, little wooden stores went up in a line down a muddy road, and that became Michigan Avenue. Eventually the little wooden stores made way for bigger brick stores, and finally Gately’s Peoples Store at 112th.

The ancient, dilapidated wooden house at the end of their own block on Wabash, where Steve’s friend Jack Cassero lived, was a Little House in Roseland, said Mrs. Bertolucci. Jack’s house had once stood on a prairie farm, looking at twinkling stars in the dark night, long before Mayor Daley’s city workers installed blazing mercury vapor streetlights in the early 1960s.

Mrs. Bertolucci was quite correct, as far as she went. But like all of us, she only went as far as she knew. And for all the time Mrs. Bertolucci had spent reading about ancient Greece and Rome in her one year of college at St. Xavier’s, she knew only the big events in the history of her own city, and nothing really about the land that became Chicago. There was Fort Dearborn, then a big fire, and then the Loop got built. Mrs. Bertolucci didn’t know what Indian tribes had lived in the region, or if they had nearby settlements, so she didn’t mention any of that. See “When Chicago Wasn’t Chicago” in Notes for more on that time period.

Here’s one way to imagine Chicago before Chicago:

“To the east were the moving waters as far as eye could follow. To the west a sea of grass as far as wind might reach.”

That’s how Chicago novelist Nelson Algren described the land in the opening lines of his classic poem-book, “Chicago: City On The Make.” The prairie “moved in the light like a secondhand sea,” wrote Algren, as if he had really seen it.

A sluggish river ran through the sea of grass into the southern tip of Lake Michigan. As the river met the lake, it bent and ran a little further behind a sandbar that formed a natural breakwater sheltering what would become a bustling harbor. The river banks and surrounding prairie teemed with a plant variously described as wild garlic, leek or onion. The abundant plant led to the local Native American name for the area, “the wild garlic place” or “place of the wild onion,” spelled in English just as variously as Cheecagou, Chicagou or Chicagoua.

The local Native American tribes—the Potawatomi by then--didn’t live permanently in the area where the river flowed into the lake. Their two closest settlements were northwest, at the Des Plaines river; and just south of Lake Calumet, which is quite close to Roseland, nearly due east.

Of course, the story reaches further back than the sea of grass and Native Americans, too. It could start with the wooly mammoths, giant tree sloths and other animals that roamed North America before the first modern humans arrived and hunted them to extinction, somewhere around 12,000 B.C.

Or the glacier that melted into Lake Michigan at the end of the last Ice Age.

Or dinosaurs.

Or a vast global sea filled with trilobites and other prehistoric sea life.

Or cosmic dust coalescing into planet Earth.

Or the unfathomably black void filling Earth’s future spot before the Big Bang.

iv. Back to Nonna

Steve wavered on the top step of his front porch in October 2003 and decided he couldn’t blame Nonna. If you were a kid like Nonna in a little Kansas mining town and you found your dead mother’s finger laying outside on the ground, he reflected, you were bound to see bad luck everywhere when you grew up. And yes, that is yet another story for another time.

He suddenly became aware that his left hand had gotten out of his Bears jacket pocket and was going for his throat—going for his scapular, that is, under the collar of his white undershirt. He stopped the hand and shoved it back into his jacket pocket. It was getting to be like Dr. Strangelove, that hand.

Steve had lived in the building at the corner of 54th Street and East View Park for over 20 years by then, but since he hadn’t grown up in Hyde Park, he was still technically new. He hadn’t lived in Roseland for over 20 years, but since he’d grown up there, Roseland was still home.

He felt all this in a few seconds, wavering on the step. He didn’t think about it, he just felt it, the same way he felt the autumn sun on his face. That’s Chicago for you.

Neighborhoods are critical identifiers. Hyde Park and Roseland were and are like any two planets in our solar system. They orbit the same source of life—in this case the blazing lights of downtown Chicago, the Loop--but at the closest point in their orbits, they remain light years apart.

So we must briefly leave Steve poised on his top step to discuss Roseland versus Hyde Park. Don’t worry. The gum, the traumatic childhood event the gum represents, St. Anthony’s, and the devil will wait for us.

The devil, especially, has all the time in the world.

Ha! First of all, that link--classic depiction of a Wonder Break rain bonnet, wow. Second, much as I hated these things as a kid, I was just watching The Queen's Gambit and I have to admit when that actress wears one in a circa 1966 or something scene, she and the plastic rain bonnet look fantastic.

You have awoken so many memories. The one I am pining over - the promotional rain bonnets. I had forgotten about them! If I didn't live in a climate where it almost never rains, I would hunt one down. https://img0.etsystatic.com/000/0/5128310/il_570xN.203175714.jpg