To access all website contents, click HERE.

Welcome to Chicago History Rabbit Hole! Regular readers know that when we dive into a lengthy digression following some interesting tidbit within a post, the Chicago History Rabbit appears as a heading. You’ll find some new rabbit hole discoveries in this section, and I’ll also gradually gather the many existing rabbit holes elsewhere on the site right here, so they can burrow together in one place.

Watch your step. This rabbit hole opened up in the February 25, 1972 Mike Royko column from Mike Royko 50+ Years Ago Today, leading to a look at the sordid past history of the South Loop…then to one of Chicago’s most famous sons…and finally to arguably the biggest single tragedy in Chicago history.

February 25, 1972

“The morning’s first defendant in the gloom of the Chicago Av. Police Court was a striking, curvy, platinum blond, wearing pancake make-up, dark eyeshadow, tight purple slacks, a mid-length coat, and shiny black boots,” Mike starts off.

“The blond’s name is Harry and he hangs around Rush St. The charge was disorderly conduct.

“Judge Thomas J. Janczy, after a moment of confusion over whether it was ‘his bond’ or ‘her bond,’ sent Harry on his way.”

As you can see, the opening of today’s column reads like “The Man With The Golden Arm” if it was written by Mike Royko rather than Nelson Algren. You’re just waiting for Captain Bednarski to show up.

“Then came a few winos, one without shoelaces or socks, and a few seedy-looking wife beaters and their punchy looking wives. It was the usual crowd of rundown and kicked-around people who show up in any police court on any morning.”

Finally the clerk calls “Louis Tornabene…disorderly conduct….”

Mike apparently got a tip that Lou Tornabene, who was on the federal list of “Chicago’s top 100 Chicago Cosa Nostra gangsters” ten years earlier, would turn up that morning in the Chicago Avenue police court.

“He was said to be a lieutenant to Gussie Alex, the Syndicate’s downtown boss,” writes Mike. “Vice was the Tornabene specialty. He used to run a Syndicate place called the Eddy Foy Club, at 754 S. Wabash. It specialized in entertaining conventioneers. The entertainment was provided by B-girls, strippers and prostitutes.”

For Younger Readers: By the early 21st century, “B-girl” has come to mean girls who are either break dancers or involved in hip-hop culture. But its original meaning, throughout most of the 20th century, was Merriam Webster’s first definition: “a woman who entertains bar patrons and encourages them to spend freely”. In other words, women paid by an establishment to hang around the bar and get men to buy more drinks.

Mike says Eddy Foy’s Club shut down after the newspapers “finally brought some heat.” Soon, he says, Tornabene did a year in prison for loan fraud, and dropped out of sight until today.

In court as Mike watches, a man with a German accent testifies that Tornabene, now a car salesman, sold him a vehicle. The man claims he told Tornabene he had bad credit. Tornabene sold him the car anyway—then demanded the car back the next day.

When the man brought the car back, he says Tornabene demanded a $25 rental fee, or he’d shoot him. The man refused, and claims Tornabene punched him and chased him as he ran out.

“Tornabene was in close pursuit, shouting: ‘You German bastard. Germans never pay their bills,’” Mike writes. The man “said he answered over his shoulder: ‘(Bleep) all Italians’”. Mike doesn’t have to tell his contemporaneous readers that these are very realistic details for the time period. For future Future Readers, FYI, this little dialogue exchange adds a genuine note of veracity to the witness’s testimony.

Tornabene denies the charges and the judge throws the case out.

Now, get this: Mike apparently messes with Tornabene on his way out! Unless Mike is quoting someone else crazy enough to screw with a former mobster:

“As Tornabene walked into the corridor, somebody stopped him and said: ‘Things have changed, haven’t they?’

‘“What’ya mean?’ he said.

“‘From the days of Eddy Foy’s Club.’

“‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ he said with a scowl. ‘I’m a car salesman. Just a car salesman.’”

Mike’s conclusion is that the sexual revolution drove Tornabene to sell cars.

“The things he used to provide are now given away quite freely in our society. You can even see them on the silver screen. But apparently Tornabene still remembers how to handle a disgruntled customer.”

Lots to dig into here!

First: Not surprisingly, Mike was correct that Louis Tornabene was a mobster, and associated with Gussie Alex. Several FBI reports are available online concerning Tornabene’s activities in the 1950s, including a lengthy report by agent William Roemer Jr., who became the most highly decorated FBI agent ever, helping convict Chicago Outfit leaders Sam Battaglia and Felix “Milwaukee Phil” Alderisio. Roemer was working on the FBI’s “Top Hoodlum Program” when he filed a 1959 report including these tidbits:

And:

Eddie Foy’s Club at 754 S. Wabash, and everything else that used to be on that block, is now the fancy schmancy Columbia College Student Center.

Here’s what Eddie Foy’s used to look like, with undying gratitude to Chuckman’s Photos on Wordpress:

Also thanks to John Chuckman, we have an Eddy Foy matchbook:

Which all explains this letter to the editor in the Chicago Tribune on July 30, 2007:

Good thing Rex Bartholomew’s family was less familiar with the nature of Eddie Foy’s Club.

Eddy Foy’s was succeeded at 754 S. Wabash by the Blue Star Lounge, and then became the first site of Buddy Guy’s Legends, until Buddy Guy moved a block north. To help you further visualize this area, a block west on State is where the Pacific Garden Mission used to be, now replaced by the colossal, amazing expansion of Jones College Prep. Just behind there is Printer’s Row and Dearborn Station, the former railroad station now housing Jazz Showcase and, last I looked, a Bar Louie. (There’s a terrific place nearby called Half Sour, too, where the Blackie’s used to be at Polk and Clark.) A little farther south on Wabash from Eddy Foy’s old spot are, among other upscale attractions, the South Loop Trader Joe’s and Eleven, the tasty modern Jewish deli.

I’m so used to the current inhabitants of these blocks that I had quite forgotten what a seedy area it used to be, gradually starting to improve during the ‘80s with little islands of gentrification here and there.

I checked in with Chicago Cultural Historian emeritus Tim Samuelson, knowing he would have some thoughts. Thank you, Tim!

Tim Samuelson:

The place [Eddy Foy’s] was definitely "all mobbed-up" as were many similar enterprises in the South Loop along State and Wabash. This area - particularly State Street - had a reputation for illicit enterprises going back into the late 19th century. State from Van Buren to 22nd was known as "Satan's Mile" - and the similar enterprises along Wabash were a spill over.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, area businesses preyed on new arrivals entering the city at Dearborn Street Station, but by the last half of the twentieth century the area's clientele was largely conventioneers staying at nearby hotels. In the late 19th century, the saloon of Michael Finn at State and 11th streets was said to have originated the knock-out drink known as the "Mickey Finn." Greenhorn new arrivals would stop there after getting off the train. When they regained consciousness, they found themselves in the alley minus their wallet, watch, jewelry - and sometimes even their clothes.

The most famous of the South Wabash dives of the later era was the 606 Club - a legend of its genre. It was the showcase for the best in burlesque and strip performances. There is an untrue urban legend that Mayor Richard J. Daley and John F. Kennedy met in a back room at the 606 to strategize winning the Democratic presidential nomination. And to carry this urban legend further, it is said that Chicago's postal zip code "606" was selected as a winking tribute of appreciation for this momentous meeting.

I got a good chuckle when it was decided to name Chicago's North Side park on an abandoned railroad right-of-way the "606". They didn't have a clue. "606" was also the name of a treatment for venereal disease. Seedy tourist magazines of the era ran ads offering the "606 Cure" to unlucky visitors.

Tim Samuelson, by the way, thoroughly researched both the zip code and Daley/Kennedy stories, so they are truly debunked. Of course, Tim also came up with a matchbook from the 606:

To be thorough, here is the 606 Club in the early ‘60s—

—and the location today.

Too bad they didn’t designate south Wabash and State historical districts, then require facade-ectomies, so that all the new buildings here would be fronted by things like the neon signs of the 606 Club and Eddy Foy’s. That would be much better than most of the new stuff, like this thing on the 600 block of south Wabash. To be fair, the Columbia College student center is quite nice.

In Mike Royko’s February 25 column, Mike says Eddy Foy’s shut down after newspapers “finally brought some heat.” In looking into that, I found still more interesting evidence of what a seedy area the South Loop used to be. Come with me down this rabbit hole too, you won’t regret it.

The Chicago Tribune only mentions Eddy Foy’s—spelled “Eddie”—in a short series of articles in April 1964, when it came to light that Cook County Building Commissioner Erwin Horwitz and his chief building inspector were part owners of a land trust that held the 754 S. Wabash building, where Eddy Foy’s Club took up the ground floor. These articles say the club closed on March 21, 1964 “when Internal Revenue Service officials padlocked it and seized the property for failure to pay excise taxes.” Unfortunately, I have no further information on that—but read on anyway.

When the news first broke that Commissioner Horwitz was the landlord for the notorious Eddy Foy strip joint that just got shut down by the IRS, then-Cook County Board President Seymour Simon called him in to talk about it.

“Simon said Horwitz reported he had not been in the building for more than eight years and [the building inspector] told him he had visited the club premises several times in the last few years but saw nothing wrong. Both told Simon they had no knowledge of any illegal or immoral conduct there.”

At first, President Simon decided landlords aren’t responsible for their tenants and said the matter was closed, without gathering further evidence. But pretty soon, it turned out Horwitz also owned the building at the southwest corner of State and Van Buren, which housed yet another notorious “B-girl joint,” Crossroads. Crossroads had just gotten its liquor license revoked. Simon was forced to do something.

“I am confronted with a moral or ethical consideration whether his [Horwitz’s] connection with buildings makes him unfit or unsuitable as building commissioner,” Simon told the Trib after this new revelation. “I am not in disagreement with the position that a person who knowingly does business with hoodlums or permits illegal activities should not be an employe of the county, especially at the level of high responsibility.”

And by the way, I know how to spell “employee.” The Tribune back then spelled it “employe” because the paper was still following the preferred spellings of Tribune owner Col. Robert McCormick, who believed the English language needed to be simplified and that he was just the man to do it. That’s why old Tribune stories are full of words like “thru” instead of “through.” Col. McCormick had been dead for almost ten years in 1964, but “employee” was still “employe” in the pages of the Tribune.

Horwitz resigned as building commissioner, and Seymour Simon accepted his resignation “with regret.” I should note for confused regular readers that in our 1972 timeline, Seymour Simon is a Chicago alderman. That’s because Mayor Daley kicked him off the County Board—a whole other story—and Simon went back to City Council before eventually ascending to the Illinois Supreme Court.

Crossroads must have been housed in the former Rialto vaudeville theater, going by its matchbook and location at 336 S. State. The following matchbook and Rialto photo are both courtesy of the amazing John Chuckman’s Photos on Wordpress. If that website ever disappears, I will cry.

And here’s the site of the Rialto Crossroads today. The park is where the Rialto used to be, and of course beyond it is the Harold Washington Library.

For the full story of how the South Loop changed from the home of Eddy Foy’s Club and the Rialto Crossroads, into a place full of restaurants, condos, fancy schmancy college buildings and the Harold Washington Library, the place to go is Lois Wille’s 1998 book— “At Home in the Loop: How Clout and Community Built Chicago’s Dearborn Park.”

Coincidentally, Lois Wille started at the Chicago Daily News in 1956, and would become a great friend of Mike Royko’s. She would win the Pulitzer Prize and wind up editorial page editor at the Daily News, then the Sun-Times, and finally the Tribune. Wille was one of the first women to break out of the society pages and work her way up to such a position on a Chicago newspaper. Rick Kogan’s wonderful obituary for Wille, who unfortunately passed away in 2019, includes this Royko quote from when Lois Wille retired:

“Over the years, I’ve seen lots of Pulitzer Prize winners in action, but I have never seen anyone who is superb at everything, except Lois. She’s brilliant…a superb writer, great reporter, marvelous organizer.”

Kogan also talked to Judy Royko, Mike’s wife, who said the book “One More Time: The Best of Mike Royko” might not have happened without Lois Wille:

“She was essential to its creation, to helping select the columns and to writing introductions to each section that not only captured Mike as a writer but as a person.

“I really believe she knew Mike better than anybody else, and we became so close working on the book. Lois was so much more than a friend to Mike and then to me and our kids, Sam and Kate. She was family.”

As elegant as it would be to end here by bringing it all back to Mike Royko, there are two rabbit holes left.

Who was Eddy Foy?

Eddie Foy Sr. was one of the most famous entertainers of his time, with his heyday running from the 1880s until his death in 1928. He was born Edward Fitzgerald in New York but moved to Chicago at age six after his father’s death.

Foy grew up here, and was considered a hometown boy. He was a popular vaudevillian who made it big on Broadway, then touring the country with hit shows. His name is variously spelled “Eddy” or “Eddie.”

Foy was so famous, there are 1,669 entries in the Tribune archives for his name. Besides reviews of his many shows, there are scads of articles covering everything from what he said in a barbershop, to how he reacted when a rude waitress spilled soup on his nice new gray pants—the writer expressing wonderment that Foy wasn’t funnier in real life. The waitress seems to be working off a script for an early Norman Lear sitcom:

Foy: What’s the matter with you? Are you crazy?

Waitress: Yes, I’m crazy!

Foy: Well, why do they keep you in a public dining room?

Waitress: To wait on actors.

Then there are the display ads for Foy performances, and eventually come the entries for his son, Eddie Foy Jr., who was a successful dancer and actor in films and then television, dying in 1983. Finally, the Foys dwindle out in increasingly rare TV guide listings for the 1955 movie “The Seven Little Foys”—though the movie is still shown, including on TCM. Bob Hope plays Eddie Foy Sr. as he and his seven children create and perform one of the most successful vaudeville acts of all time.

Eddie Foy remained a star until his death, and the name remained well known via his son. Besides playing his father in four movies, Eddie Foy Jr. appeared in movies like “Pajama Game” before segueing into numerous TV appearances through the ‘70s.

As you can see, Eddie Foy Jr. is practically a twin for his father.

If you can stand to watch Bob Hope, here’s a clip from the Seven Foys movie with Jimmy Cagney playing George M. Cohan, tap dancing on a long table with and without Bob Hope as Eddy Foy. As two successful Irish entertainers of the same period, of course Cohan and Foy knew each other. That clip is actually well worth watching for Jimmy Cagney’s dancing. Bob Hope’s dancing isn’t awful.

And here’s a YouTube tribute to Eddy Foy Sr. made up of clips from the movies in which Eddy Foy Jr. played his dad. The first scene is from Cagney’s “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” in which George M. Cohan and Eddie Foy meet for the first time. It’s pretty hilarious, because you can tell Eddie Foy Jr. is really hamming it up, doing an over-the-top imitation of his dad, and I think Jimmy Cagney breaks character because Foy Jr. is cracking him up.

Eddie Foy Sr. was particularly known for being hilarious in drag. Here he is in the hit play “Mr. Blue Beard,” playing “Sister Anne,” as pictured in the Chicago Tribune review on November 24, 1903, when the show opened the new and acclaimed Iroquois Theater at 24-28 W. Randolph. This is why the name of Eddie Foy may be familiar to some readers well versed in Chicago history. We’ll return to Eddie Foy the comedian, but first, we must pay our respects to the Iroquois Theater.

The Iroquois Theater Fire

The first three-quarters of the “Mr. Blue Beard” review is devoted to raptures over the Iroquois Theater itself:

“Wonder and unqualified admiration were the willing tribute paid to the new Iroquois theater last evening by the pronouncedly fashionable audience that assisted at its formal opening and dedication…Only the Auditorium equals it in impressiveness and beauty, and the Auditorium is of course a thing apart and not to be classed among the theaters of the city.”

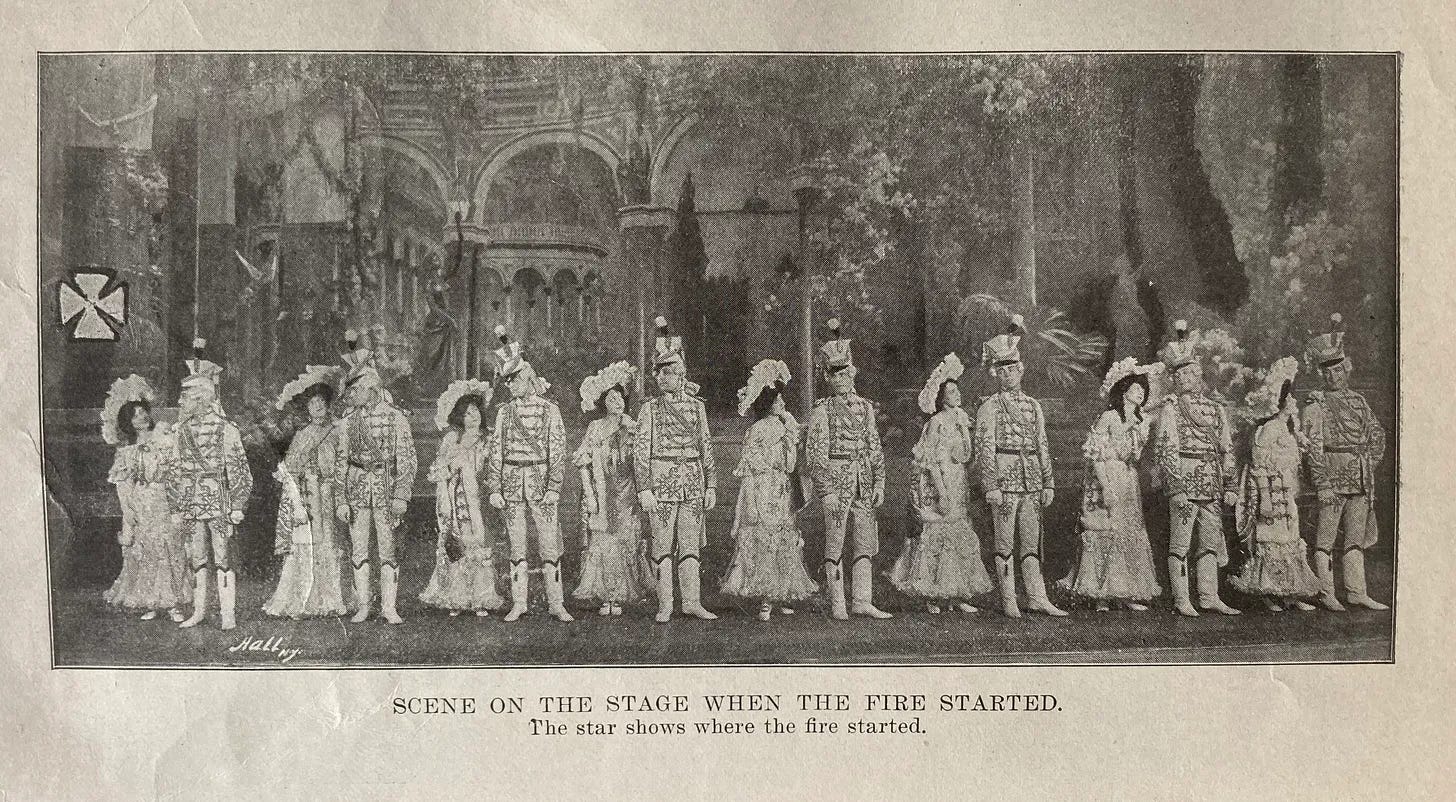

All pictures are from this 1904 Memorial Edition of “The Great Chicago Theater Disaster: The Complete Story Told By The Survivors” by Marshall Everett, identified in the book as “The Well Known Editor and Descriptive Writer.”

The Iroquois Theater, the review went on, is “a place where the noblest and highest in dramatic art could fittingly find a worthy home. That the noblest and highest in dramatic art may, perhaps, not find its home there, does not alter the fact that the theater is a place of rare and impressive dignity—a theater about as near the ideal in nearly every respect as could be desired….A curtain of deep red velour is used between scenes, a brilliantly colored autumn landscape decorates the act drop, and a woodland scene is on the fireproof curtain. All in all, a theater of surpassing beauty, comfort, and completeness.”

The review was less enthused with “Mr. Blue Beard,” if only because its costumes and scenery were not as dazzling as previous spectacles, specifically “The Sleeping Beauty and the Beast” or “The Wizard of Oz.”

“It is, of course, a brilliant spectacle, but it is not the equal of those we have already enjoyed and possibly, we are spoiled,” writes the critic. “Of story there is little or none—nobody expected there would be any, and nobody cared because there was none. There is the usual loving couple who have hard times getting their love affairs to running smoothly, there is the usual wicked persecutor of the maiden in this enamored couple—in this case he is Mr. Blue Beard—and there is, of course, the regulation good fair and the magic horn which calls her to the hero’s aid when matters get a bit too complicated.”

…. “Of the company, Eddie Foy is the chief and ablest performer. He has little that is really amusing to do, but his personality is in itself so good natured, his humor so infectious and his clearness at funmaking so great that he cannot fail to win the tribute of applause and laughter from his auditors.”

Foy sang two solos— “I’m a Poor Unhappy Maid” and “Hamlet Was a Melancholy Dane.” Per the review, “the latter being given in connection with a Foyesque impersonation of Ophelia.” So Eddie Foy was so big, a performance could be “Foyesque.”

“Mr. Blue Beard” played for six weeks, until an unusually crowded holiday matinee on Dec. 30, 1903. That day, a standing room only crowd of over 2,000 people—largely women and children—packed the supposedly fireproof Iroquois Theater.

Soon after the start of the second act, the theater erupted in flames after a stage light apparently short circuited and set a backstage curtain on fire, which quickly spread among all the flammable scenery and curtains.

The National Fire Protection Association still lists the Iroquois Theater fire #5 among the deadliest fires and explosions in U.S. history, with 602 deaths. The frenzy that followed that first spark is horrific and well-documented.

The theater was said to have an “asbestos curtain” that could be brought down to separate the audience from all the flammable materials backstage in event of a fire. But the curtain got caught on something, and didn’t come down.

In any case, a representative from the fire curtain company who appeared at the coroner’s inquest a week later admitted that the reputedly fireproof asbestos curtains were not, in fact, fire proof. And the Iroquois Theater curtain had never even been tested.

There was one small fire extinguisher backstage, which a stagehand unsuccessfully tried on the initial flames.

Exits were covered with thick curtains. Passages from upper floor seats to exits were narrow and dark. Many of the exterior doors were bolted shut, and others used inside mechanisms that panicked audience members couldn’t operate. The skylights were nailed shut.

One usher literally refused to open an exit for the terrorized crowd trying to escape a fire clearly raging out of control.

People were trampled, or incinerated by a fireball that erupted like “a cyclone” from the stage into the audience, or asphyxiated by poisonous gases from the burning backstage materials.

Some who made it out onto an upper story fire escape were pushed from behind to their deaths on the cobblestones below. At the coroner’s inquest, one witness described watching a man fall from the fire escape onto several bodies, then get up unhurt since his fall had been cushioned—only to be crushed by a woman plummeting from the fire escape after him.

In all this horror, Eddie Foy stood out as a hero. Foy had been in a downstairs dressing room preparing for his next scene when he heard strange noises coming from backstage. He’d left his son Bryan there, so he ran to check, and saw the start of the fire. Foy testified he rushed Bryan to a backstage door and gave him to a man there, then ran back to the stage to try to calm the audience so the crowd wouldn’t panic and cause a stampede before the fire curtain came down.

As the Tribune account told it, “Nearly every witness who preceded him had told of Foy’s heroic efforts to prevent panic, standing on the stage with the fire falling all around him while he tried to quiet the audience.” The subhead over Foy’s testimony is “When Clown Becomes a Hero.”

Several more pictures from “The Great Chicago Theater Disaster” before we continue:

The theater was repaired and re-opened as the Colonial Theater, and later replaced by the Oriental Theatre—recently renamed the Nederlander Theatre.

For more, I would recommend you to the marvelous Chicagology site’s Iroquois Theater page .

Wrapping up Eddie Foy

Not surprisingly, Foy was more complicated than his “clown” image. Early articles mention his deep knowledge of Shakespeare, and Eddie Foy Jr. once told the Tribune’s famed and/or infamous critic Claudia Cassidy that his father used to look at the racing pages over breakfast, muttering all the while—but he was muttering Shakespeare lines. His dream was to play Hamlet.

On the other hand, Foy’s sister had to sue him in 1916 for child support. Foy had left her to bring up his illegitimate daughter Catherine and apparently neglected to send funds. His sister got a judgement for $7,235, which according to an inflation calculator is a rather amazing $186,615.21 in 2022 money.

And there are at least two more strange Eddie Foy stories.

Weird Eddie Foy Story #1

In 1895, a Clarence “Whitey” White was among a burglary ring accused of robbing the Norman Ream residence at 1901 S. Prairie Avenue, taking $4,000 worth of jewelry and furs. At that time, this block of Prairie Avenue was still among the most exclusive address in the city. White and pals were found with the some of the stolen goods—and then it turned out at least one cop was working with the gang.

Somehow they weren’t convicted, and a month later Whitey and a pal drove up to two detectives holding two more of their friends in custody. White started a shoot-out to free his friends, but things got “too warm” and he drove away.

The Berry detective agency sent some agents looking for Whitey, and they ended up shooting and killing his brother Frank instead.

“Frank White was a hard-working, honest boy and well-liked by his neighbors. He drove a wagon for the Reid Ice Cream company and owned the horse he was driving when he was killed,” wrote the Trib.

It turned out Frank White was driving his brother Clarence (Whitey), who was planning to get out of town after that shoot-out. Clarence White eventually turned himself in with his lawyer, and told a great story of being ambushed by various detectives—getting away, while his brother Frank was killed.

“The stains of the poor boy’s blood and brains are on my coat still,” he testified later. Two Berry detectives were indicted for murder. After one detective was convicted for murdering Frank White, Clarence White disappeared with “a number of warrants” still against him for burglary.

Soon, White was under arrest again and on trial for the murder of Thomas J. Marshall during the robbery of the Golden Rule Store. “Nothing can convince me that I was mistaken when I pointed out Clarence White as the murderer of Mr. Marshall,” insisted the cashier, Miss Mattie Garretson, in court. But apparently Whitey looked a lot like another habitual criminal, a John Orme. Two other witnesses ID’d White too, but Miss Garretson eventually relented on her own identification.

The trial was nuts—the judge threatened to quit, leave the city, and write a book about Chicago justice, ending with the Clarence White case. In a wild final courtroom scene, all three men accused of murdering Thomas J. Marshall were finally acquitted.

But just before that verdict came in, who saunters into the courtroom but the famous Eddie Foy:

.

Weird Eddie Foy Story #2

About six months after the Iroquois Theater fire, Eddie Foy was starring in a show called “Piff, Paff, Pouff” when he got on the New Haven railroad to travel from Manhattan to his vacation home in Harrison-on-Sound. Per the Trib, “a lunatic seized him by the throat and began choking him.”

“‘Hold on there, partner,’ said Eddie, as he tried to raise himself from his seat. ‘Wait a minute until I talk this subject over with you.’

In the 19th century, people talked a lot prettier even while being strangled, it seems.

“‘You want to murder me,’ cried the insane man. ‘You are the man I am after.’ In a moment the car was in an uproar. Commuters who recognized the comedian rushed to his assistance, but the mad man waved them aside. The actor fought desperately, and finally when the conductor and several passengers broke the man’s hold, the latter raved and threatened to send everybody to eternity. Foy became calm and said: ‘Now, my friend, be quiet. We will take good care of you.’”

Make of all this what you will. Clarence “Whitey” White was clearly a habitual criminal, whether or not he murdered Thomas Marshall. Yet, of all the possible available actors in the city, Eddie Foy recruited Clarence White for a role.

Then, a little while after the Iroquois fire, somebody tries to strangle Eddie Foy on a train.

And why the heck would Eddie Foy Jr. put up with a strip joint in downtown Chicago using his and his father’s name? Was this the equivalent of whoring out the family name in some bad TV commercials?

And there are more Eddie Foys to consider.

This Eddie Foy was incarcerated at Leavenworth. From the scant record that goes with this mug shot, it appears he lived July 3, 1895 to November 5, 1957, and this picture may have been taken in 1930.

Among other criminal Eddie Foys, one was accused of murdering a druggist named Clarke in 1886, in between incarcerations for burglary. Could Eddy Foy’s Club be named for one of the many Irish criminals of early Chicago?

Beats me. Maybe the name “Eddie Foy” was simply incredibly common—there were an awful lot of Irish people around at the time. Maybe as Eddie Foy Sr. became famous, more hoodlums began using the moniker as a funny nickname.

Heck, maybe Eddie Foy Jr. started the club as a regular bar, sold it, and when it turned into a strip joint, he had to put up with it.

If anybody knows, let us all in on it.

If you came here from social media or another site section such as THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 or Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today, you may not know this is all part of the book being serialized here: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

To get new Chicago History Rabbit Holes and other section posts directly to your emailbox, SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE!

Hi - I am a token collector and I have an Eddy Foy's Cocktail Lounge token. It is good for 5 cents. It is made of brass and is scalloped. In case you aren't familiar with tokens - it is about the size of a quarter. But, with the shape and scalloped edges seems to be 1930's or older. So perhaps if you check out a Polk directory from 1930's or older (perhaps you library has a collection of the Polk directories) you might find your answer... In the meantime, I am willing to part with this token. You can email me at dunmoving331951@gmail.com