Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today: A column that rivals a Shakespearean sonnet

Weekly Compilation Oct. 25-31, 1971

To access other parts of this site, click here for the Home Page.

Why do we run this separate item, Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today? Because Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the serialized novel central to this Substack, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” lived in a Daily News household. The Bertolucci’s subscribed to the Daily News, and back then everybody read the paper, even kids. And if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko. Read our Royko briefing Monday-Friday on Twitter, @RoselandChi1972.

October 25, 1971

The old man and the farm

Today is the first appearance of a classic column always included in Royko compilations, for good reason. It is a love sonnet rivalling Shakespeare, written to an old Wisconsin farmer who “was short, almost dwarf-like, and built so squarely he seemed to have no neck.”

It’s a sonnet to the old farmer, but also to every immigrant who ever came here with nothing, broke their back to make good, and didn’t think they’d done anything special. The old farmer is my grampa and my gramma--perhaps yours too, or your mother or father. Maybe it’s even you.

Mike Royko’s father, Mikhail, was literally born as his peasant mother picked potatoes in a field in Ukraine, Richard Ciccone recounts in his wonderful biography, “Royko: A Life In Print.”

After 5-year-old Mikhail’s father died, his mother left her children at her sister’s farm and went to America to earn money and send for the children later.

At their aunt’s farm, the Royko children literally had to fight their cousins for food for four years. I used the word “literally” twice so far because I really mean “literally,” not because I didn’t bother to find a synonym. Then they joined Mike Royko’s gramma in Chicago, where 9-year-old Mikhail immediately went to work running errands and such in South Side steel mills.

So Mike Royko knew this old farmer well, though they had never met.

Back to the column.

Mike has stopped at this old man’s lonely northern Wisconsin farm upon seeing a hand-lettered cardboard sign reading “Fresh honey.” In a heavy Slavic accent, the old farmer invites Mike inside, takes $2 and hands him two jars of honey from a cupboard stuffed with jars. He pours Mike a shot of vodka.

Mike learns that the farmer came from the old country in 1900, and worked for 12 years in Pennsylvania coal mines to earn the money that bought his 800-acre farm. The old farmer and his wife cleared the entire 800 acres of trees and rocks, by themselves.

As Mike leaves, he shakes hands with the old farmer: “I’ve never seen a hand quite like it. The fingers were so stubby, they all looked like thumbs. The hand was dark and calloused from the wrist to the cracked nails.”

Finally, Mike’s killer ending.

“You got regular work in Chicago?” asks the old farmer. “Good….Is that hard work on newspaper? Hard work?”

“I told him that I used to think it was. But not anymore.”

October 26, 1971

What TV really needs

Today Mike unknowingly touches off media events that will affect the course of Chicago TV news into the 21st century. Mike has done something that will come to haunt him, personally, for several decades. I wonder how many readers remember their Chicago TV news history well enough to guess what that is. I mean besides Rob Feder. Don’t worry—stick around as this project progresses and you’ll find out.

This is something I especially love: A Royko column lost to time because it would never be judged worthy of putting into a collection. Oh, the humanity.

This column, unlike 99% of all Royko columns, features photographs--three small headshots across the skinny column: Lon Chaney as the Wolfman on the left, Charles Laughton as Quasimodo on the right, and in the middle, a pleasant well-coifed middle-aged white man in a suit and tie.

“You may have proved my point already,” Mike starts. Which picture did you look at—the Wolfman, Quasimodo, or “the third face, the one with the sincere grin, the clear eyes, the well-trimmed hair?” Mike knows everybody looked at the Wolfman and Quasimodo first.

The third guy is Bob McBride, a news anchor “brought in from Detroit by Channel 2 to thrill us with his nightly readings of the 10 o’clock news.” Mike now mocks the heavy-handed ad campaign leading up to Bob McBride’s debut the night before.

And to be fair, the Ch 2 ads were completely over-the-top. As I scrolled through microfilm collecting stories for October, I was annoyed by Bob McBride too. Channel 2 was running a full-page ad in every paper it seemed, every day, with a giant picture of Bob McBride and the headline, “If you watch Fahey or Floyd, you’ll miss one of the most important events on WBBM-TV’s history. The Chicago television premiere of Bob McBride.”

For younger readers, that's Fahey Flynn, venerable anchor at Ch 7, and Floyd Kalber, venerable anchor at Ch 5, with whom Ch 2 is trying to catch up in the ratings with alleged wunderkind Bob McBride. Remember, this is 1971—there’s only three major channels, plus WGN Channel 9 and Channel 11. If you’re lucky, your antenna might also get you get 32, 44 and or even 66 on your UHF dial.

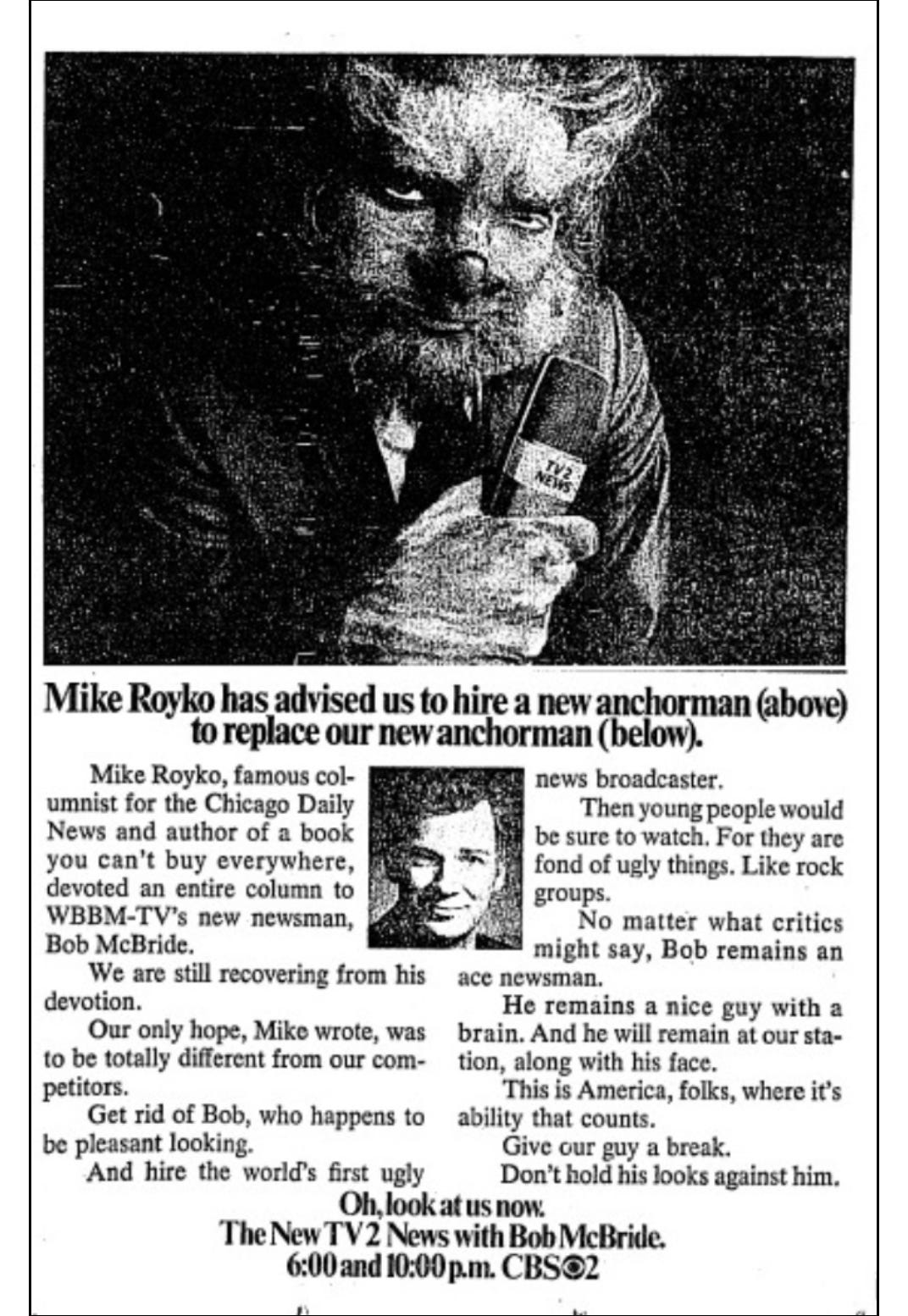

Unfortunately, I found Bob McBride so annoying I didn’t copy any of those pre-debut ads. But here is Channel 2’s first follow-up ad, which will give you a good sense:

“Because his arrival is a major civic event, according to Channel 2, I was sure to watch,” writes Mike. “As far as I could tell, McBride did a decent job…He displayed a sincere gaze, a square jaw, an attractive haircut and a well-knotted tie.”

“In a key news moment—when it was time to joke with the weatherman—he had just the right jocular tone,” Mike assents. But Mike insists that’s not good enough, that McBride will “go the way of Bob Jamieson and Wayne Fariss, Pete Hyams and Bill Kurtis, and all the other new, exciting readers…where are they now?”

Well, of course, Bill Kurtis is on “Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me,” and apparently makes every documentary you ever see anywhere. But on this date in 1971, Bill Kurtis had kind of disappeared from the media scene.

Mike says what Channel 2 needs instead of a nice guy like Bob McBride is “a really ugly TV anchorman…I mean a face who will make your jaw drop and your wife scream when he appears on the screen.”

Advertising experts say the youth market is most important, Mike notes, and the youth would love an ugly anchorman. “Their heroes, the rock stars, are probably the ugliest creatures not in captivity.”

More mature viewers would like someone ugly too, he says, “at least here in Chicago. The leading municipal heroes are Dick Butkus, Mayor Daley and Kup, none of whom resemble Tab Hunter.” Sorry, can't skip a Dick Butkus reference—proud son of Roseland, remember!

But Mike’s words, for once, are not the best part of this column. I could make you wait for this to happen in our 1971 timeline, but I can’t wait either so here goes:

As you can see, Channel 2 took Mike’s bait and ran this ad repeatedly during November—mostly full page. Mike once said the Tribune always made the hair stand up on the back of his neck, but all thanks and praise to the Trib for digitizing their entire history so I could search “Bob McBride” and “display ad” to find this.

October 27, 1971

How to beat the tax laws

Mike writes today about Frank Cerone, the obscure cousin of Chicago mobster Jack Cerone, best known as one of the mobsters convicted of skimming $2 million off a Vegas casino, the basis for the movie “Casino.” Wikipedia says Cerone helped perpetrate the almost unbelievably grisly murder of mobster William “Action” Jackson in 1961. Follow this Wikipedia link for details only if you have a very strong stomach. I mean it. It’s so much worse than you are imagining.

Early on, Jack chauffeured Chicago Outfit boss Tony Accordo, and briefly succeeded him too. But today’s column is about Jack’s obscure cousin, Frank. Frank just runs Jack’s bookie joints on the North and Northwest side and suburbs, but he has done something unprecedented.

“He’s done something that few people, gangsters or otherwise, have been able to do,” writes Mike. “He doesn’t pay any income tax. Not a nickel. And he gets away with it.” Frank files his return, but doesn’t pay. So long as you file, “you aren’t open to criminal prosecution.”

Mike points out that anybody can do the same—but the IRS would slap liens on everything they own and charge huge penalties.

Frank has that part figured out—“there is no record anywhere that Frank, or his wife Mary, own anything.” Frank once foolishly bought a car, and the IRS took it. “That was the last time he owned a car,” says Mike, concluding, “Think about him the next time you make a payment.”

When young Steve Bertolucci from Roseland read this column in his family’s copy of the Daily News in 1971 at age 10, he was puzzled. His parents shrugged and didn’t want to talk about it. His dad snorted and glanced involuntarily toward their neighbor’s house, the Siciliano’s, for some reason.

If you’ve read up to Chapter Two, you know Steve grew up to be a tax accountant. So I asked him about this column. Now Steve is the one who shrugs. “What’s his point?” he says now.

So it’s true? I asked him. As long as you file, they can’t send you to jail for not paying? “For debts?” Steve asked. “No. It’s not 17th century England. But you’ve gotta be willing to live like that, right? You’re not gonna own anything for the rest of your life. Is it worth it?”

October 28, 1971

$85 union debt wrecks career

Mike introduces today’s column as “A study of the careers of two Chicagoans.” First is “Ronald G. Becker, age: 35; occupation: sheet-metal worker.” You know #2 is going to be a big shot jerk, and the fun is waiting to find out who.

Becker went to Washburne Trade School, served an apprenticeship, and finally joined the union. He married young and had seven kids, so he needed that union salary. Even so, at 35 he just last year had enough money for a down payment on the modest home below, in the South Side Longwood Manor neighborhood. I’ll omit the exact address, though as Older Readers know, newspapers used to include the exact home address of everybody in an article, even a bystander who just casually answered a reporter’s question.

This nicely kept bungalow looks like the one I grew up in—small front room, maybe three bedrooms, one bathroom, kitchen with a dinette just barely big enough for the kitchen table. Seven kids definitely fills up that house. I hope they finished the basement.

Ronald Becker finally shoehorned his seven kids into that bungalow, but then he was so short of cash that he fell behind $85 in his union dues. The union suspended him, so he couldn’t work, and they wouldn’t let him pay his dues plus another $815 initiation fee as a penalty—not until the union board met and voted on it. Then the board kept putting him off.

Becker started driving a cab all night and looking for work during the day, while a lawyer from Legal Aid tried to talk to the union lawyer. The Legal Aid lawyer quit because the union lawyer wouldn’t return his calls for over two months.

Now Mike compares poor Ronald Becker with Michael Daley, son of the real Mayor Daley, and brother of Mayor Richard M. Daley. Michael Daley wasn’t a great student, says Mike, but he went to prestigious St. Ignatius High School, then law school, and immediately had a “wonderfully successful law career” with the “firm of Daley, Reilly and Daley,” which “has all the clients it can handle.”

One of Michael Daley’s clients is Ronald Becker’s sheet-metal union, but Daley wouldn’t talk to Mike either to explain why he wouldn’t talk to Ronald Becker’s lawyer. “Unions are, of course, (Michael Daley’s) father’s most faithful political backers,” notes Mike.

“If we had been able to talk to (Michael Daley), we might have broadened the conversation to such fascinating subjects as how much his law firm is paid by the unions each year” or “how unions will provide huge defense war chests when their top men are caught stealing from pension funds, lavish fat pensions on union bosses, while tossing a guy like Becker out of his life’s work over a lousy $85.” Mike also wonders how much the sheet-metal union has given Mayor Daley’s campaign funds.

“It’s wonderful how quickly a man can rise only two years out of school,” Mike concludes. “And depressing how far another man can plunge 10 years after apprenticeship.”

October 29, 1971

Tom and Ray a restful pair

A helpful citizen and Daily News reader strolling down the street sees two guys sleeping in a car with a sign in the window reading “Board of Election Commissioners.”

Next thing you know, Mike Royko has pictures of the snoring bozos and he’s tracked down the license plate. The license plate belongs to Thomas Cozzi, “who is listed on the city payroll as an investigator in the elections department.

“And the department has only seven investigators.” So Mike is surprised when he shows the pictures to the No. 2 guy in the department, and No. 2 says, “These are not OUR fellows.”

Mike drops by Stanley Kusper’s office, then chairman of the Chicago Board of Elections. Assistant Dennis Gallivan takes the hit. “We got caught with our proverbial pants down,” he admits.

Mike asks where the two investigators are now. “They are out in the field,” says Gallivan.

“Of course,” writes Mike. “And I hope it was a restful day, out in the field.”

Directly below Mike’s column is the headline “Kusper suspends 2 pending probe.” Since the News was an afternoon paper, they had time to report that the two sleeping investigators were suspended at a hearing Friday morning after Mike Royko caught them sleeping on the job.

WEEKEND EDITION

October 30-31, 1972

As we here all know, weekends could be sad for a Daily News family because Mike Royko wasn’t in the Daily News’ single weekend edition. So we look for Mike elsewhere on the weekends. Today, everyone enjoy this vintage Daily News wire photo of a ‘60s-era Mike. We have one reader who used to be a night copy boy at the Daily News, and fetched Mike cheeseburgers. I wonder if this is what Mike looked like at the time? My dad had those exact same glasses.

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Mike already trimmed the verbal fat, so he doesn’t need to be summarized Reader’s Digest-style, either. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, but especially to give the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. You can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there are some columns covered here you will never read elsewhere. If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career and including a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

Do you dig spending some time in 1972? If you came to MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY from social media, you may not know it’s part of the book being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

To get MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY in your mailbox weekly along with THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 and new chapters of the book—

SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE!