To access all site contents, click on the rose icon in the upper left corner or HERE.

Why do we run this separate item, Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today? Because Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the serialized novel central to this Substack, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” lived in a Daily News household. The Bertoluccis subscribed to the Daily News, and back then everybody read the paper, even kids. And if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko. Get your Royko fix on Twitter too— @RoselandChi1972.

June 5, 1972

Did Mike just have nothing else to do last Friday, or was his legman away from their desk getting some coffee so Mike picked up the phone?

I’d love to know, since this is definitely the only time Mike Royko procured a bridal gown for one of his readers.

“The phone rang late Friday afternoon and a young woman, in a trembling voice, said:

“‘Can you help me with a terrible problem? I’m supposed to get married Sunday, but my wedding gown won’t be ready.’”

Thomasina McWeeney, a typist at the Gresham Avenue police station, was set to marry policeman James Volkman. “They had set the date way back in February. She wanted to be a June bride. And she would wear a gown made by Priscilla of Boston.”

What possessed her to call Mike Royko? This, we will not find out.

“You’ve heard of her, haven’t you?” Thomasina naively asks Mike.

Mike, of course, doesn’t know from wedding dress designers. But Thomasina’s wedding dress, which should have already arrived at the local bridal salon, is from the foremost bridal designer in the country.

Nearly everyone on the internet today writing about Priscilla of Boston—aka Priscilla Kidder—credits her with Grace Kelly’s 1956 wedding dress-to-end-all-wedding dresses.

Which is strange because everyone writing about Grace Kelly’s wedding dress credits the real designer, Helen Rose of MGM, and the properly identified dress is owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which features the dress on its website (though it is not on view at the museum just now).

So Priscilla Kidder didn’t get that plum Hollywood job, but she did design Grace Kelly’s bridesmaid dresses. Priscilla snagged the assignment via her friend Stanley Marcus of Neiman Marcus. That gig propelled Priscilla from a small profitable bridal salon in Boston to national prominence and sales.

Priscilla’s bridesmaid dresses were yellow organdy. The puffy sleeves were much admired at the time.

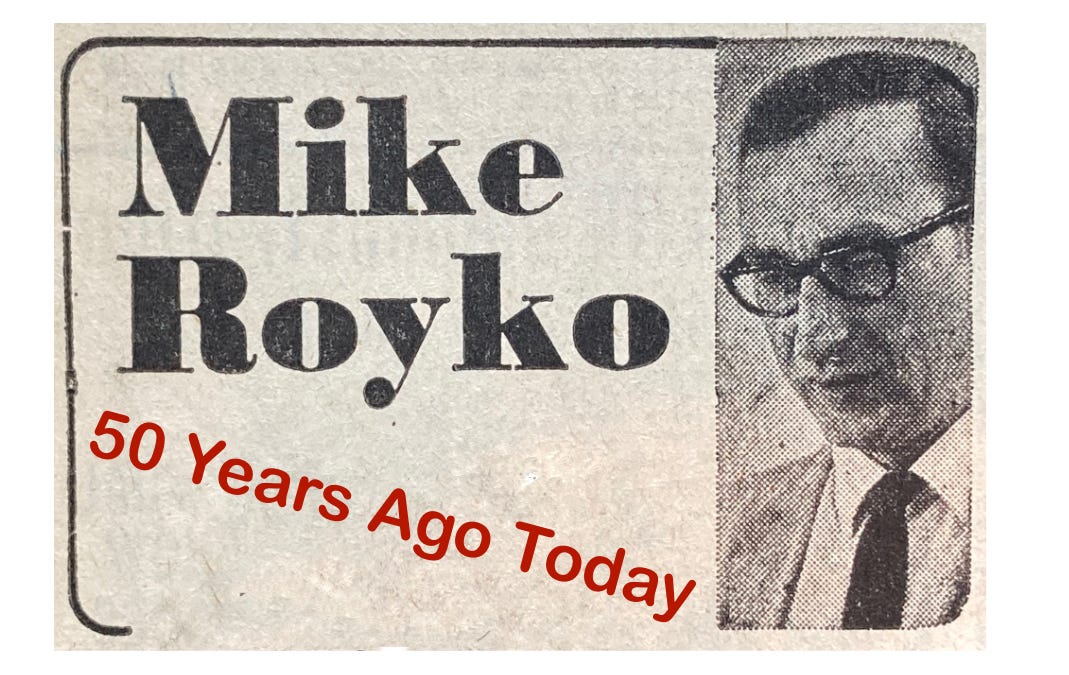

Publicity from the Grace Kelly wedding drew orders from American royalty, including President Johnson’s daughter Luci, and later President Nixon’s daughters Julie and Tricia.

Luci and Tricia both made the cover of Life in their Priscilla of Boston dresses. Tricia’s dress was controversial for being sleeveless, if you can believe it, in 1971.

Per the Tribune’s Louise Hutchinson, Priscilla moved into the White House a few days before Luci Johnson’s wedding and rode in the limousine to church with the bride and groom’s mothers, in order to oversee the dress and its train. Priscilla did the bridesmaids dresses too, and “instructed the bridesmaids…how to walk in their gowns and how to sit in the limousines that took them to the shrine.” At the church, “The minute Luci stepped out, Mrs. Kidder rushed forward and straightened the train. Luci paused twice on the shrine steps for photographs. Each time Mrs. Kidder fussed with the train. When Luci walked, she held the train up.”

So this must be Priscilla Kidder, holding the train rather awkwardly:

Priscilla of Boston remained the top name in weddings throughout the 20th century, but began to seem expensive and stuffy in the early years of the 21st. Priscilla herself died in 2003, a year after her company was sold to May Department Stores. The company changed hands again before landing with the more mainstream David’s Bridal, which shuttered Priscilla in 2011.

You can still buy used and heavily touted Priscilla of Boston dresses from online bridal sites. Her dresses topped out at $10,000 as the company closed, which is about $13,000 in 2022 money. Thomasina spent $300 on hers, which is $2,025 in 2022 money.

Mike says he decided to help Thomasina McWeeney so she’d get a new name right away, “whatever it would be.”

Readers of the Future: In 1972, women changed their surnames to their husband’s when they got married. No, really, they did.

Mike calls the bridal salon, where the manager explains that if Priscilla’s doesn’t make the dress and send it, there’s nothing he can do. So Mike calls Priscilla.

There’s a little back-and-forth with the receptionist, who doesn’t know who Thomasina McWeeney is.

“Thomasina McWeeney in Chicago,” Mike explains. “She’s getting married Sunday and she wants her gown, and if she doesn’t get it there’s going to be hell to pay.”

“Pardon me?”

“Everyone in Chicago is going to find out that the Nixon girls can get their gowns from Priscilla, but not Thomasina McWeeney.”

Mike holds for Priscilla, who he imagines apparently as Zsa Zsa Gabor.

But Priscilla, as it turns out, “talked like a drill sergeant.”

Mike gives us delicious, long, unbroken quotes from Priscilla.

“I’ve been here since 5 a.m. And I’ll be here until 1 a.m. Every girl in the United States wants a Priscilla gown. I tell the stores not to take orders with less than 11 weeks’ notice. For Pete’s sake, we have to get fabrics from all over the world, and then we have to make the gown. But they still take orders with only eight weeks’ notice or less, even though we warn them.

“And if we don’t take the order, do you know what happens? Some of them threaten to sue. I swear, every father in this country must be a lawyer. One goofy guy even threatened to bomb my place if I wouldn’t make his daughter’s gown.”

Still, Priscilla promises Mike that Thomasina will get her dress. “I’ll be here all night, and so will my girls. I don’t know how we’ll do it, but it’ll get there.”

The dress arrives at O’Hare at 4 a.m., met by the bridal salon manager. Thomasina, in the Priscilla dress, made it to St. Catherine’s Church in Oak Lawn on time—

“and now [the dress] is in a trunk where it will remain until she can show it to her grandchildren.”

Or, you may be able to find it at a resale bridal gown website.

June 6, 1972

The Steven Rand Corp. of Northbrook is distributing brand new fiberglass replicas of the old Ford Model A, “with a modern, powerful V-8 engine and other contemporary mechanical parts.”

The company offers a new Model A to Mike for a day, and it’s a toss-up as to whether they would have been pleased with the publicity.

Mike has a good time, but advises at the end that you’ll need a truss or a strong Teamster working as your chauffeur in order to steer it.

“And I can suggest some wilder ways to spend $7,000,” Mike adds. That’s $47,250 in 2022 money.

The real Model A, of course, was pretty slow. So Mike has fun peeling away from stoplights and astonishing the other drivers in this new powerful Model A— especially one young guy who pulls up at a red-light and says, “Hey, dad, what’s that?”

“This is a Model A, sonny,” Mike tells him. “They were made in the late ‘20s, before you were born, a regrettable event whenever it occurred.”

“‘Hey, that’s groovy,” sneers the young guy. ‘What’s the top speed, dad—thirty?’”

Sometimes the most surprising thing in 1972 newspapers is discovering that people talked like that in real life, not just in period sitcoms and “Laugh-In.” Mike may not have quoted himself entirely accurately there, but he’s quite clear that this guy really called him “dad”—twice—because this infuriated Mike. So the young guy probably said “groovy” too.

Another interesting marker of time: Mike drives the new Model A on the Dan Ryan and Kennedy, and notices that surprised drivers inevitably speed up to draw alongside and stare. Then, the drivers feel compelled to go faster than a Model A, and pull ahead.

To check his observation, Mike tests it.

“As an experiment, I went 60 miles an hour,” he writes. “Cars did 65 or 70 to look. I went up to 70. They went 75 or 80…

“So if you want to goad others to drive at suicidal speeds, and maybe someday cause the most fantastic of accidents, this is a practical vehicle.”

Can you imagine a time when it was unusual for Chicago expressway drivers—especially Dan Ryan drivers—to go 75 or 80? Now, of course, it’s more suicidal to go slower.

June 7, 1972

Mike looks at the race to replace former Ald. Fred Hubbard, who recently disappeared during his first term in office along with $100,000 from the nonprofit group he headed, which was supposed to get Black Chicagoans into construction jobs.

Even though Hubbard ran as the anti-Machine reform independent candidate, beating the William Dawson organization.

As Mike puts it, after Hubbard won, “He quickly reformed from being a reformer….Many other aldermen are still puzzled by what Hubbard did. They can’t understand why he didn’t learn that an alderman can quietly accumulate $100,000 and not have to run away.”

Two leading candidates are Fred Barnett—“best known for one accomplishment: He was Fred Hubbard’s victorious campaign manager”—and Arnette Hubbard, “best known in the ward for being the wife of the disappearing Fred Hubbard.”

Then there’s William Flower, who Mike wrote about in his June 2 column. Flower, a minister, believes he received heavenly instructions to run for Hubbard’s seat in a dream.

“This isn’t the first time somebody ran for alderman because of a dream, but none of them has admitted what he dreamed being an alderman would be like.”

In a few weeks, Mike concludes, the second ward will no longer be without an alderman.

“Maybe they should leave well enough alone.”

June 8, 1972

“From now on, it will be hard to look at Hubert Humphrey without feeling embarrassed for him,” Mike leads today.

“It’s the kind of embarrassment you feel for someone when they want something so desperately they will debase themselves.”

Hubert Humphrey has done something almost unbelievable: He said he could accept fellow presidential candidate Alabama Gov. George Wallace as his Vice President.

Wallace continues recuperating in the hospital from his recent assassination attempt, from which he will be permanently paralyzed.

Mike constructs the rest of the column like so: First, one or two paragraphs going over the accomplishments of young, then middle-aged Hubert Humphrey working for civil rights when it was hard to do so. Next, a paragraph about who George Wallace is.

The contrast is damning, of course.

Mike remembers 1948, when young Hubert Humphrey “shook up the Democratic convention by leading the fight for a then-radical civil rights plank in the party platform”.

Then, young U.S. Sen. Humphrey “proposed an anti-lynching bill, the creation of a civil rights commission, a fair employment practices law, a bill outlawing the poll tax, job discrimination, and Jim Crow in transportation.”

…. “Now, in the hope of picking up some Southern delegates, he says that if circumstances are right, he can run with George Wallace. George Wallace, who less than a decade ago was standing on the steps of a state university, an American governor trying to prevent black American citizens from going to a state school.”

And so on.

We all know what George Wallace stood for, but this column is rather heartbreaking for the points about Hubert Humphrey that many have probably forgotten, such as:

“When President Johnson signed [the Civil Rights Act] into law, he gave Sen. Humphrey one of the pens. And on a copy of his speech about the civil rights law, he inscribed:

“‘To Hubert Humphrey—without whom it couldn’t have happened.’”

Mike’s devastating conclusion:

“Humphrey once jokingly said of his own political ambition:

“‘I’m like the girl next door—always available.’

“It looks like the girl next door has hung a red light in her window.”

Bonus:

June 8, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Letters to the Editor

Remember last week when Mike told President Nixon what he needed to give Leonid Breshnev along with the gift of a Cadillac Eldorado? Daily News reader Joan Roma has another perspective.

If you dig Mike Royko, you’ll want to see the news he’s writing about. Check it out here!

June 9, 1972

Mike saw an ad for Amtrak the other day, and decided to take the train to the upcoming Democratic convention in Miami. Amtrak advertises that people can relax on a train.

“I have been riding trains for years,” writes Mike, “because I am convinced that if I get on an airplane, I will die. If not from a crash, from fright.”

That’s actually true—Mike had severe fear of flying. Former Tribune political reporter (later managing editor) Richard Ciccone remembers flying home from D.C. with Mike just after meeting him for the first time—and uses the anecdote to start his biography of Mike, “A Life in Print.” Mike wrote a column about that flight a few days later, on January 24, 1977. See the Weekend Edition below for their dueling versions.

In today’s column, Mike gives us a history lesson when he notes that until Amtrak recently took over cross-country trains in a taxpayer-subsidized system, he would have had to make train reservations based on what train line serviced his destination. Before Amtrak, he would have called the Illinois Central to make a reservation to Miami; Penn Central for New York; and the Santa Fe to head west.

Now he can call one number, Amtrak.

So Mike calls the number. Again, and again, and again. It’s always busy.

That’s another history lesson—there used to be busy signals! Younger Readers, a busy signal was an incredibly annoying sound. Short, obnoxious, constant beeps. When I googled to find it for you and tested the YouTube version below, my dog almost jumped out the window.

By the time Mike has tried calling for almost two hours, he writes, “Amtrak would have to pour three martinis into me, and hum a lullaby, to make me relax.”

When the phone finally rang instead of giving Mike a busy signal, it went on ringing. And ringing. And ringing.

Mike keeps hanging up and calling back. After about almost three hours, he finally gets a human being on the phone and makes his reservations in about eight or nine minutes.

“With my left hand, I loosened the grip of my right hand on the phone, and placed it gently in the cradle. Then I slammed my fist down on it once.”

Mike congratulates Amtrak.

“It would have probably taken me at least 10 minutes more than that to take a cab to O’Hare, board a plane, fly to Miami, and get off the plane. And I’d be a nervous wreck.”

June 10-11, 1972

As we here all know, weekends could be sad for a Daily News family because Mike Royko wasn’t in the Daily News’ single weekend edition. So we look for Mike elsewhere on weekends.

So we’ve run into Mike’s fear of flying for the first time here in “Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today.” Let’s look at Royko biographer Richard Ciccone’s account of flying from D.C. to Chicago with Mike in 1977, which opens his 2001 book—versus Mike’s version of that flight in a column written a few days afterward.

In 1977, Ciccone “realized exactly how many people read Mike Royko” when his phone started ringing as soon as Mike’s column appeared. People Ciccone hadn’t talked to in ten, 15 years called him—in a time when the only way to find people was to call Information (if I recall, you dialed 411), or write Bee Line or Action Line. In 1972, those public service newspaper columns are full of people hunting for long lost relatives.

Here’s how this fateful flight came about: Ciccone and Mike were both in Washington for President Jimmy Carter’s 1977 inauguration. Naturally, they met in a bar frequented by reporters. Ciccone was due for a 8 PM flight out of then-National Airport, getting him to Chicago by 10 PM. Mike planned to board a train the next day, and arrive home the day after that.

Ciccone told Mike that was crazy. He should fly home that night with Ciccone.

“I’m afraid to fly,” Ciccone recounts Mike telling him. “I was on a plane in the service that almost crashed.”

“You don’t fly?” someone in the bar asked Mike, according to his column. “Sure I fly,” Mike answered. “I flew as recently as 1953. That was only 24 years ago.”

Ciccone:

“Just a few more martinis and you won’t be afraid of anything,” I said.

Mike:

My terror, I explained proudly, is so powerful that it resists every cure known to man.

“Get drunk,” said Dick Ciccone, a Chicago reporter.

There is not enough booze in Washington to overcome my fears.

“I’m flying back to Chicago tonight,” Ciccone said. “I’ll bet you can do it if you try.”

I cannot resist a bet. “Waiter,” I said, “a double martini.”

The scientific experiment had begun.

Ciccone:

A few more drinks and I had convinced Royko to come to the airport. He resisted at every step. When we got out of the taxi at National he announced that he was getting a cab back to the bar. I persuaded him to go inside the terminal. At the ticket counter, he protested that he didn’t have enough money. I told him they’d be happy to take a credit card. He bought the ticket, and we proceeded to the gate waiting area.

“I can’t do this,” Royko said. He began shouting, “I’ve got a bomb, I’ve got a bomb.” Two airline security people came running up. I convinced them Royko was hopelessly drunk. Terrorist bombing was not a real fear in 1977. The security people gave us a smirk and allowed us to board the plane.

Note: For context, Ciccone’s book came out early in 2001, so he wrote prior to the September 11 World Trade Center terrorist attack. I’ll attribute the blasé attitude re plane bombings of everyone in this story to the general amnesia about skyjacking even at the height of the phenomenon—which was 1972, only five years before this flight.

In ‘72, there were 59 skyjackings worldwide and 14 fatalities; of those, 28 hijackings involved U.S. airlines. Yet when Mike wrote his June 9, 1972 column covered above, the FAA still didn’t require something as basic as putting all passengers through metal detectors, and the airlines wouldn’t do it on their own.

Since nobody else cared enough to stop skyjackings, in our 1972 timeline, the U.S. Air Line Pilots Association recently voted to boycott flying to countries that wouldn’t prosecute or extradite skyjackers. The International Federation of Airline Pilot Associations voted on June 8 to ground all planes worldwide for 24 hours on June 19, 1972 unless the United Nations took action against hijacker-friendly countries.

Even so, airline employees themselves in 1972 were lackadaisical about checking boarding passengers. On March 10, 1972, Mike wrote a column about two stewardesses who were considering quitting their jobs due to the sloppy airline security. “Anybody with a gun or a bomb who wants to get on a plane can do it,” they told Mike—or plant a bomb.

Bottom line, I don’t get it, but people just didn’t start taking bombs and guns on planes more seriously until it later turned into a purely terrorist phenomenon, rather than random lunatics and criminals. September 11, 2001, of course, clinched that.

But to be clear, during the skyjacking craze which had just ended prior to the 1977 flight Ciccone and Mike describe, bombs were often used both as threats by skyjackers who were physically aboard planes, as well as by extortionists who called airlines claiming to have planted bombs aboard planes. In March 1972, TWA employees found a typed noted demanding $2 million placed in two duffle bags and ready to be dropped somewhere, or a bomb would go off in four TWA planes--one bomb every six hours, starting at 1 p.m. and ending at 7 a.m. the next day. After searching all their planes, TWA found a 5-6 pound plastic explosive in a jet at Kennedy Airport. Later, a bomb they had not found exploded in the cockpit of a parked jet in Las Vegas, ripping it apart. So bombs were a real thing.

Back to that 1977 flight.

Ciccone:

As the plane engines revved up for takeoff, Royko unfastened his seat belt and bolted for the door. A stewardess insisted he sit down.

Mike:

Then we were walking through this tunnel and I was sitting down in this long, large room with lots of other people.

“Is this the waiting lounge?” I recall asking.

Ciccone laughed. “This is the inside of the airplane.”

“I can’t do it,” I yelled, and turned to run. But it was too late. They had closed the door.

I began babbling about my civil rights being abused when this pretty lady leaned over me and said something. I don’t remember what she said, but she had freckles and nice teeth.

Ciccone:

We were at the front of the plane, only a few rows back from the curtain separating coach from first class, and everyone could hear the ruckus he was causing. As the plane climbed, one of the first-class passengers stuck his head through the curtain and said, ‘That’s Mike Royko, let him come up here with me.’ The interloper was Charles Stauffacher, chairman of Field Enterprises, which operated the Chicago Sun-Times and Daily News. Royko dragged his new best friend—me—along and we settled in first class. The wise stewardess quickly slipped two glasses of vodka into our hands.

Mike:

I shouted: “I need a drink!”

People kept coming up to me and giving me little bottles filled with fear-killer. I guess they wanted the experiment to work. Or me to shut up.

Then this guy came down the aisle, apparently curious as to the source of the bedlam.

When his face came into focus, I bellowed: “Hiya Charlie, you ol’ son of a gun. What the hell are you doin’ here, Charlie? Have a drink, ol’ pal.”

Charlie is the president of the company that owns this newspaper. Boy, do I know how to make an impression on the boss.”

Ciccone:

Also sitting in first class was the heavyweight champion of the world, Muhammad Ali, who was traveling with his wife and infant daughter. Ali was lifting the child high above his head. She was giggling. Royko walked over and introduced himself to Ali, who replied with a sullen look. He clearly had no idea who Royko was. “I’m the only guy who defended you when you changed your name from Cassius Clay,” Royko proclaimed. Another sullen look.

Royko tried another tack. “You’re not that tough, you know. You ever hear of Tony Zale? Tony Zale was the ‘Man of Steel’ from Gary. Never got knocked out. Tony Zale would have kicked the shit out of you.”

Ali handed the baby to his wife. I thought, “He is going to get up and with one punch hit both of us and we will be dead.”

Instead, Ali reached behind his back for an airline pillow, turned his face from us, and closed his eyes.

Mike:

….I was howling about how terrified I was. People decided to be kind.

“Look who is aboard,” someone said, leading me down the aisle.

I looked. It was Muhammad Ali, of all people. He was bouncing a baby—his, I was told—on his knee and saying, “goo goo”

“See?” a stewardess said. “Even the little baby isn’t scared.”

“You’re right,” I said. “Ask Ali to bounce me on his knee.”

Me and the champ talked.

“Hi, champ.”

“Hiya.”

“Joe Louis would have torn your head off.”

We didn’t talk anymore.

Mike’s conclusion:

Will I do it again, now that I’ve done it once?

Sure. In another 24 years. That will be the year 2001. I’ll get smashed and go to the moon.

Unfortunately, as we all here know, instead Mike had already left us by 2001. At least Dick Ciccone’s biography was also released that year.

WEEKED EDITION BONUS

Here’s an ad from the June 9 Daily News, offering you the chance to get Mike Royko thrown on your front porch five times a week, plus the weekend edition. Oddly enough, it doesn’t say anywhere how much the subscription costs.

If you send this in and it doesn’t work, here’s the next best thing:

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Mike already trimmed the verbal fat, so he doesn’t need to be summarized Reader’s Digest-style, either. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, plus the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. You can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many iconic columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there’s riveting work covered here you will never read elsewhere.

If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career which includes a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

Do you dig spending some time in 1972? If you came to MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY from social media, you may not know it’s part of the book being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

To get MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY in your mailbox weekly along with THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 and new chapters of the book—

SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE!