Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today: Attack of the 10-story Mayor Daley

Weekly Compilation June 19-25, 1972

To access all site contents, click on the rose icon in the upper left corner or HERE.

Why do we run this separate item, Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today? Because Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the serialized novel central to this Substack, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” lived in a Daily News household. The Bertoluccis subscribed to the Daily News, and back then everybody read the paper, even kids. And if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko. Get your Royko fix on Twitter too— @RoselandChi1972.

UPDATE on last week’s column of June 15, 1972: In “Penny-ante bystanders,” Mike told the story of Bob Donofrio and Rena Friedman. The young couple got mugged when they sat down near Oak Street beach on a beautiful summer night, lost track of time, and were attacked by two muggers. Bob gallantly distracted the muggers so Rena could get away, while Rena literally ran across Lake Shore Drive, stopping cars and screaming for help to save Bob.

It’s like a Chicago “The Gift of the Magi,” but with a great, unironic ending. The two guys in the luxury high-rise who won’t call the police for Rena unless she gives them a dime is a great twist worthy of O. Henry, but the story didn’t end there. Our heroine, Rena, runs back out on the street and right into a carful of plain-clothes cops, who then scare off the muggers and give the couple a ride home.

I wondered if Bob and Rena stayed together, got married, and told their story to children and grandchildren. Somehow I forgot that I could try to find out.

Indefatigable reader Bernie Cicirello took the initiative and found the answer:

“Apparently, Bob and Rena did get married and had a daughter,” he writes, with this attachment from the Tribune on January 13, 1978—it also ran in the Daily News:

Thanks, Bernie! That is heartwarming.

June 19, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Letter to the Editor

This letter responds to Mike’s June 13 column, “Generation of vandals,” in which Mike took a tour of the beautiful landmark Auditorium Theater with managing director Monte Fassnacht, who described all the awful ways that fans at rock concerts destroy pieces of the gorgeous architectural and interior design details of Adler & Sullivan masterpiece.

Like H.M., I was surprised that rock fans destroying the Auditorium hadn’t been previously reported. But as I mentioned last week, I couldn’t find any mention in the Daily News or Tribune archives, so it appears that Mike got a tip and broke this story. That is, of course, what reporters do, and Mike does it all the time—so I guess H.M. and I should not have been surprised.

June 19, 1972

The official 100th anniversary celebration of the Chicago Fire in 1971 didn’t excite many people, writes Mike, “besides firebugs.”

“But it might have if one of the wildest ideas ever hatched in City Hall had come about.”

The wild idea was overseen by Col. Jack Reilly, inevitably ID’d in Chicago newspapers as “Mayor Daley’s director of special events.” Not Chicago’s director of special events, mark you. Mayor Daley’s director of special events.

Mike enjoys mocking Colonel Reilly, a character from Chicago history who comes complete with eye patch.

Actually, I don’t think it’s really an eye patch, although that’s how it’s always described. In more clear pictures, I believe you can see that the Colonel simply had a black lens in the left side of his eye glass frames. Maybe I’m wrong. Let’s just say eye patch. Way more interesting.

Younger Readers will not know the Colonel, and even many Older Readers may not have heard the name, though it was household-level in Chicago for the entirety of Mayor Daley’s reign. Let’s have a peek at Col. Jack Reilly.

First, the “eye patch,” because it seems to be the reason Col. Reilly became a piece of Chicago history:

Col. Reilly’s 1988 Tribune obituary says the eye patch followed mid-1950s eye surgery that caused him to quit his job with the city Building Department. In a 1974 interview with Ellen Warren, then with the Daily News, Reilly said he ended up with the eye patch because he was “too busy” for cataract surgery and put it off.

“I never would take time off,” he told Warren. “Stupidly.”

But in a classic case of a City Hall door closing and a better window at City Hall opening, newly-elected Mayor Daley immediately created the role of director of special events just for Col. Jack Reilly in 1955.

Many sources (including Reilly’s Trib obituary) credit the Colonel with inventing the now classic tradition of dying the Chicago River green on St. Patrick’s Day, but Ron Grossman’s 2017 look at St. Patrick’s Day traditions in the Tribune gives that honor to Stephen Bailey, a business agent of the plumbers union. My money is generally on Ron Grossman.

However, getting the credit for dying the river green shows you the size of the shadow Colonel Jack Reilly cast across the Chicago landscape during his 22 years as the city’s director of special events. What Col. Reilly definitely did do was invent Chicago’s Venetian Night in 1958, starting it off in grand style with 400 boats. Venetian Night is recognized as the city’s oldest ongoing festival.

The Colonel ran five of Mayor Daley’s six inaugurations, and he also oversaw the Mayor’s funeral in 1976.

Before Mayor Daley (B.M.D.), the Colonel was born in 1899 in Ossining, N.Y. and served in World I, rising to sergeant. Back in Chicago, he eventually landed in Samuel Insull’s PR department, and ended up running the 1933 World’s Fair. Col. Reilly moved on to running the 1939 New York World’s Fair, then rejoined the service for World War II, becoming a lieutenant colonel and serving as military governor of Mannheim, Germany in the post-war years.

After retiring from the military, the Colonel came back to Chicago, where he oversaw special events for the Chicago Railroad Fair, and then for the Museum of Science and Industry, before joining the city building department. Presumably, during all those stints the Colonel had many opportunities to meet and schmooze with Richard J. Daley, which paid off big-time.

As Mayor Daley’s head of special events, the Colonel was by definition everywhere something was happening. His exploits, then, are also a record of Mayor Daley’s reign, which is a record of mid-century Chicago.

In 1959, Col. Reilly organized Queen Elizabeth’s Chicago visit. The queen and Prince Philip were set to disembark from their yacht in Monroe Harbor and come ashore at Buckingham Fountain, where there would be a grandstand seating 700. Initially, the seats were reserved entirely for muckety-mucks, but that didn’t play well in the media.

So Mayor Daley sent Col. Reilly to explain how the grandstand would seat a perfect cross-section of Chicagoans, drawn from every civic organization, especially featuring “youth.” Reporters questioned how that was possible, since there were more than 700 such groups.

“Let’s not seek perfection,” Reilly told reporters. “There will be nothing to strive for in the world hereafter if we attain it here.”

Regardless, the queen’s visit did go off pretty perfectly from all accounts.

The Colonel tried and failed to control the Beatles when they invaded Chicago in 1964 to play the Ampitheatre. Reilly ordered secrecy for the Beatles’ arrival at O’Hare, to avoid mobs of fans. But the Beatles’ local press agent, Allen Edelson, called everybody with the details anyway.

Col. Reilly found out about the leak when then-Tribune reporter Tom Fitzpatrick (later Sun-Times columnist) called to ask about crowd control measures at O’Hare.

“Reilly’s reaction was direct,” wrote Fitzpatrick.

“This has been the cheapest publicity stunt in the history of the United States,” Reilly told Fitzpatrick. “There is no purpose served in announcing their arrival point.”

Col. Reilly switched the Beatles to Midway instead—see, he could do that!

But press agent Allen Edelson passed that information along to reporters too.

Edelson was the one to inform the Colonel about that leak. Col. Reilly didn’t take that well at all.

“In fact,” Edelson told Fitzpatrick, “he told me he was so mad that he didn’t care if the kids tore the Beatles apart.”

At that point, the Colonel apparently gave up keeping the arrival a secret, but he still managed to whisk the Beatles away from the airport without seeing their fans.

Paul McCartney pronounced the Colonel’s restrictions “a drag.”

The Colonel was defiant: “The city of Chicago isn’t going to be a patsy for the Beatles,” he declared.

Here’s some fabulous 1964 home movies outside and in the Amphitheatre:

In 1966, when the Rev. Martin Luther King led about 5,000 marchers to City Hall and taped a list of 14 demands to a La Salle Street door, it was Col. Reilly who removed the paper and said he’d give it to Mayor Daley later.

And according to Elizabeth Taylor and Adam Cohen’s “American Pharaoh,” it was Col. Reilly who called Mayor Daley at home on April 4, 1968 to tell Daley that King had been assassinated.

The Colonel was ripe for all lampooning. The Chicago Bar Association thus did so in its annual Christmas show in 1971, and the Tribune obligingly printed a big block of the script.

“In the opening sketch, Mayor Daley, dressed in Army frontier blues, yellow kerchief, and with large saber, enters with Col. Jack Reilly, his director of special events.”

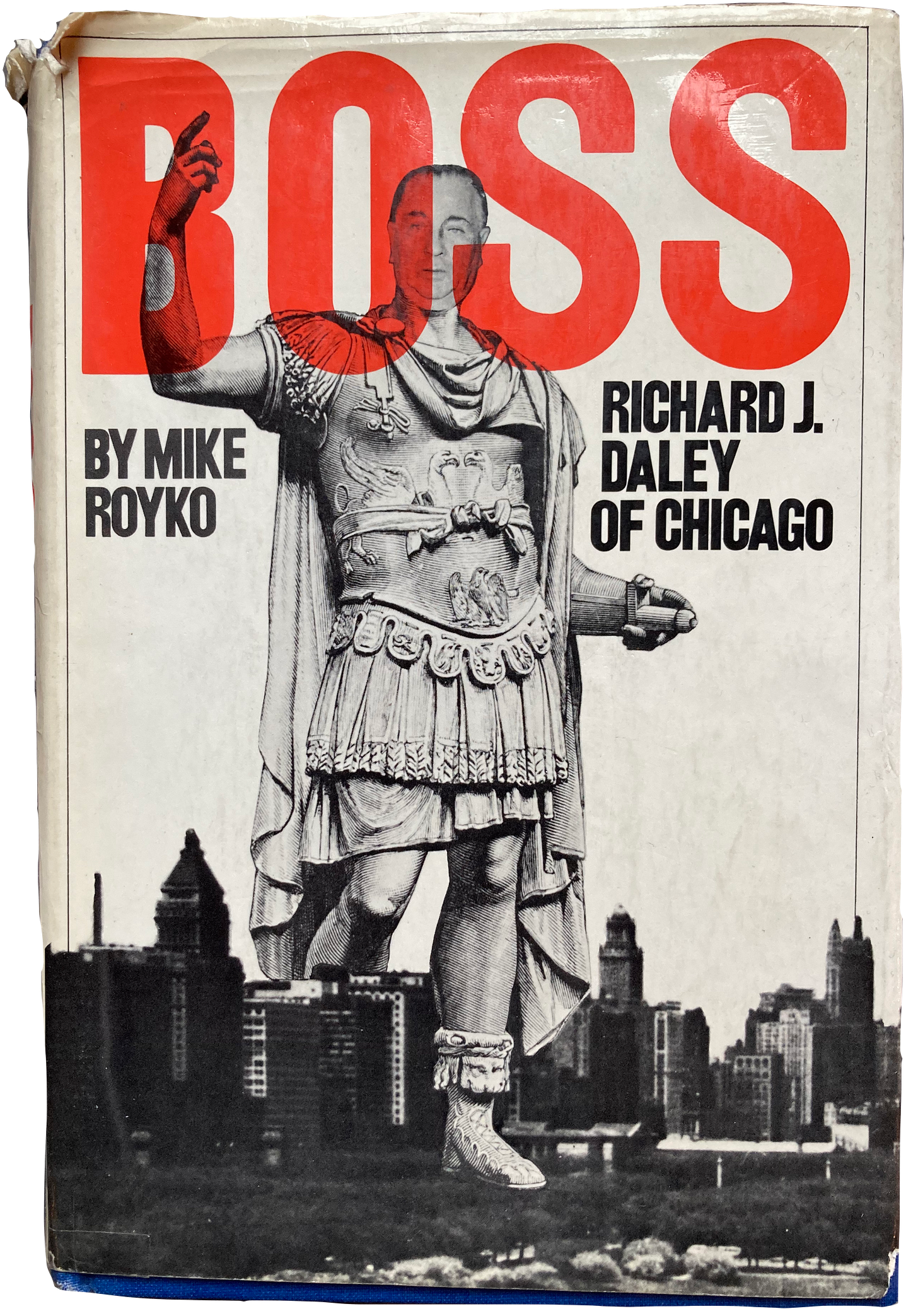

You know the lawyer playing Col. Reilly had a big black eye patch. Unfortunately, the skit was not funny so not worth quoting, though sketch Col. Reilly continually called Mayor Daley “Boss— because Mike’s Royko’s biography of the mayor had just come out.

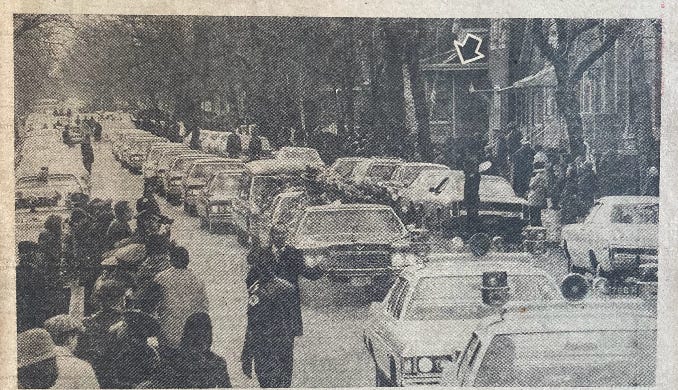

Reporters could count on the Colonel for good dialogue at any of the events he continually organized and ran. Good example, the 1968 Miss Chicago contest. The Colonel oversaw the initial competition at the Chicago Yacht Club, whittling down 40 contestants to five finalists.

George Harmon, who would go on to a long career as a professor at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism and helped at least one student avoid flunking their required newspaper internship, covered the festivities:

This year’s contestants wore circumspect one-piece bathing suits as they preened before the judges…There were some bulges in the right places and some bulges in the wrong places.

“Let me talk to the fat one,” said a judge.

“We have no fat ones,” countered Col. Jack Reilly”.

Later:

“Reilly said the finalists didn’t have to give out their addresses.

“‘Too many wolves,’ he chuckled, eyeing several young executives who had been lurking in the club since dusk.”

After the Picasso was unveiled in what was then Civic Center Plaza, the Colonel was unhappy about the space the sculpture would take away from holding events there. He told the Tribune: “If it is a bird or an animal, they ought to put it in the zoo. If it is art, they ought to put it in the Art Institute.”

You have to appreciate the Colonel’s unflagging love and devotion to Chicago, though I’m sure he confused the city with his boss most of the time. Here’s the Colonel bragging to Ellen Warren in 1974 about how he’d recently scored a Chicago visit by Olympic Russian gymnast Olga Korbut:

“I wrote a cablegram and signed Daley’s name to it—to (Soviet leader Leonid L.) Brezhnev—and pointed out to him that America is right here in Chicago.”

Now, today’s column.

Mike has learned that Col. Reilly had an idea for the Chicago Fire centennial “so bizarre that it was kept secret during the long planning stages. Then, after it was dropped, nothing about it was ever made public.”

The general idea doesn’t sound so crazy from a 2022 POV, but the devil is in the details.

“The plan was to turn Grant Park into the largest outdoor movie theater in the world, and for one week to show a giant film on a giant screen about Mayor Daley, the Chicago fire, and the city as it is today.”

An entire week, OK—that’s a bit overenthusiastic. But here are the really crazy details of this plan, which came about after Col. Reilly called a California theatrical company and asked them to come up with something spectacular:

The movie screen would be ten stories high and 13 stories wide, “attached to some kind of tower just north of the Grant Park bandshell.”

There would be a giant movie projector, necessary to fill that monstrous screen. It “would have a bulb 10 times brighter than the one used in the Palmolive Building beacon,” at this time known as the “Playboy Beacon” for the pornography magazine that owned the building at the time.

The giant projector would require special film, ten times the size of regular film.

The sound system would consist of transmitters buried underneath the grass, which would communicate with radio headsets that could pick up the soundtrack in six different languages.

Also, the soundtrack would be piped into places like the observation decks of the John Hancock and the Prudential Building, where people could watch the film on the giant screen.

The movie itself would be a Hollywood production that would begin with a 10-story high Mayor Daley since he would be projected on a screen that size; go on to spectacular scenes of Chicago taken from planes and helicopters; and finish with a recreation of the Chicago fire.

Sadly, this event did not take place.

Mike writes that Col. Reilly, who again began and famously ran the annual Venetian Night boat parade on the lakefront, was disappointed that there was no plan for a water show in front of the gigantic screen.

“The most vexing question, however, was what to do with the movie screen when the show was over,” writes Mike. “They couldn’t just leave it there. But if they tore it down, and chopped it up, people might laugh at them.”

“It was probably a wise decision,” Mike concludes. “Who knows what the impact of a 10-story Mayor Daley might have been upon planes and ships approaching in the night.”

Actually, what it makes me think of is the cover of “Boss,” minus the Roman outfit.

June 20, 1972

Background: Last week, U.S. Sen. Adlai Stevenson tried and failed miserably to unseat Mayor Daley from his traditional role as head of the Illinois delegation to the Democratic National Convention, an office Mayor Daley has filled since 1958.

1958.

For the fun details, see THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972: Fight! Fight! Mayor Daley v. Adlai Stevenson, on June 14, 15, 16, and 17.

Early in the week, the headlines were all like—

But by the end of the week, they were all like—

Which had a lot to do with the headlines in between that were all like

Stevenson claimed to have 90 votes, which was four more votes than he needed, but he dropped out of the race anyway due to pressure on his supporters. Chicago Today’s Joel Weisman gave us some specific examples of why Stevenson supporters were rethinking their votes, such as:

“Delegate Michael Bakalis, state superintendent of education, reportedly received word the appropriation for his office would be held up or cut in the legislature.”

“Several delegates who are attorneys were warned that some critical clients could decide to take their law business elsewhere if they didn’t vote for Daley.”

“One ambitious northern Illinois delegate was warned he would never be slated for state office.”

After Mayor Daley’s resounding re-election, Stevenson bitterly told reporters that “tactics used [on Daley’s behalf] disrupt the party and frustrate the rising expectations of many for a voice in the conduct of their own affairs.”

Now to Mike.

“Sen. Adlai Stevenson sounded indignant after he failed in his attempt to bump Mayor Daley as chairman of the Illinois delegation to the Democratic National Convention.

“He said some of his loyal supporters were bullied and intimidated after they let on that they intended to vote for him as chairman….They became less loyal to him when they were told that they might lose some political favors and benefits that flow from the Daley organization.”

Mike notes that in losing to Mayor Daley, Stevenson “won the sympathy” of many people he has never met, people who have gone through the same thing.

Like all the independents who gather signatures for petitions and try to get on the ballot, mostly for lower offices. Once the petitions are filed with the city clerk’s office, “somebody looks at the petition and says, ho-ho, these are no good because you did not dot your G’s or cross your I’s.”

Of course, Mike notes, “that has never happened to Sen. Stevenson. When he runs for office, the Machine’s precinct workers help round up his signatures, and if the names were written backwards in disappearing ink, they would be accepted.”

Poll watchers might protest when they see precinct captains doing imaginative things like “pulling the levers for voters”.

“But Sen. Stevenson wouldn’t know about that,” writes Mike. “Since embracing the Machine a few years ago, he is one of the candidates who benefits from the precinct captain’s skills.”

Stevenson is also unfamiliar with city building inspectors who show up before elections if someone has the wrong candidate signs in a window, or the trials of small businessmen who are “constantly being urged to buy expensive ads in strange magazines published by ward offices.”

“But Sen. Stevenson can’t very well complain about the arm-twisting of businessmen, because the money from the ads helps finance the organization he has become part of.”

“Some may remember when [Stevenson] said something to the effect that Daley was a feudal boss. But he stopped saying that when Daley ran him for senator, and somebody observed: ‘He never said Daley was a bad feudal boss.’”

“So it was surprising to hear Sen. Stevenson complaining about intimidation and arm-twisting.

“But, of course, those were his friends getting pushed around, and that was his ambition being thwarted.

“Sen. Stevenson’s motto seems to have become: ‘Do unto others, but not to me.’”

June 21, 1972

“At first I didn’t believe George Borkowski’s story,” Mike writes today. “I thought he might have been drinking too many boilermakers.”

George Borkowski makes men’s hairpieces in a shop in Arlington Heights. A customer named Al came in recently.

“I fixed him up with the top of the line, a custom job on a silicone base,” Borkowski tells Mike.

But soon after, George Borkowski and his wife were out to dinner and saw Al at another table, his head entirely bandaged. George told his wife not to ask what happened. They got out fast.

“But a few days later, Al walked into Borkowski’s shop, and he was all smiles,” writes Mike. “He pumped Borkowski’s hand and said:

“‘You may have saved my life, George. The hairpiece was the best thing that ever happened to me.’”

Al was sitting in his parked car at Arlington Race Track when some maniac raced into it at high speed.

“Glass was flying all over the place, but the pieces just bounced off the hairpiece,” George tells Mike. “He got some cuts in his forehead, but the hairpiece protected his head. He said if he didn’t have it on, his head would have been cut to ribbons.”

George asks Mike what he thinks of that.

“I told him I thought I would move to the other end of the bar, which I did.”

If you dig Mike Royko, you’ll want to see the news he’s writing about. Check it out here!

June 22, 1972

Today Mike addresses the currently raging scandal that’s taken over the city:

The papers report that the FBI thinks there’s a “hit squad” of Black police officers mixed up in narcotics trafficking, and responsible for murdering six to seven Black men gangland-style, shot in the head and dumped in the Chicago River or the Sanitary & Ship Canal.

For more details, see this week’s THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, on June 20 in particular; but also June 21 for both a news story and a Tom Fitzpatrick column; June 22; and three items on June 25.

“Every time policemen get in trouble, the blowhards who run the various police fraternal organizations loudly cry that everybody is picking on them,” Mike opens today.

We’re seeing why Mike has noted elsewhere that “most cops hate me”.

A good example of these blowhards, he writes, is the recent letter to Mayor Daley from the 6,000-strong Confederation of Police. Mike quotes the letter and supplies corrections.

The letter declares that Chicago police “are under vicious attack” because “newspapers allege corruption” and “Publicity-seeking agitators scream brutality.”

“The newspapers are not the parties who ‘allege’ corruption,” he corrects. “It is being alleged by the United States Department of Justice.”

Plus, he notes, allegations have already led to indictments and convictions for cops shaking down people for protection money. (Note: Here, Mike refers to an earlier but ongoing police scandal, in which two cops will be convicted this week for shaking down bar owners in the Austin District for protection money.)

Re the “publicity-seeking agitators” mentioned in the letter: “That’s a heck of a way to describe the FBI.”

It’s the FBI, after all, that’s “gathered evidence about policemen murdering people and tossing their bodies into the canal. While in uniform, yet. You would think they would limit their moonlighting activities to off-duty hours.”

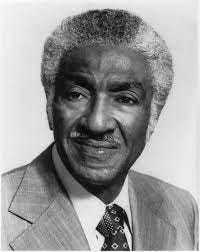

Another section of the Confederation letter says police await the “final catastrophe” of a civilian police review board—one of the main demands by U.S. Rep. Ralph Metcalfe and his Concerned Citizens for Police Reform. See TCD1972 on April 25 for the initial presentation of those demands to Police Supt. James Conlisk—

and May 24 for a Metcalfe interview with Chicago Today’s Jeff Lyon.

Mike marvels at the Confederation’s chutzpah.

“For years, scandal after scandal has been hushed up by the police force’s internal investigation unit,” he writes. “It has white-washed cases of incompetence and misconduct. A member of that unit even admitted it before a federal grand jury.”

The Confederation letter complains that police morale is low—in fact, “it simply does not exist.”

“Of course it is low,” writes Mike. “Anytime you have a scandal of this dimension, it should be low.

“I’ve never seen it as low as it was in 1960, when the Summerdale Scandal broke.

“Until that scandal—in which cops were using squad cars to haul away their loot from burglaries—policemen had easy years of scooping graft with both hands, Then it came to an end, and morale dropped.”

The letter claims the reform regime of Police Supt. Orlando Wilson, brought in from out-of-town by Mayor Daley after Summerdale, sent morale even lower. Wilson retired in 1967.

Mike has an interesting theory about the high police morale since Wilson’s retirement:

The police “have been riding a wave of favorable public opinion. They won it during the 1968 Democratic convention when they busted the heads of long-hairs, a highly popular exercise.

“Since then, they could do no wrong….So they took further advantage of this public sentiment. Now, if morale is low, it’s because they didn’t know where to stop.”

June 23, 1972

Another fun installment of “Letters, calls, complaints and great thoughts from readers”—and, of course, Mike’s response.

“MARIE NOVAK, Chicago: I read that Mayor Daley attended a conference of other mayors and urged them to get behind the President’s war policy ‘in the name of God, as fine American citizens.’

I also saw a picture of a terrified little South Vietnamese girl, burned by napalm, dropped by our South Vietnamese allies, running naked down a street. Her face was contorted in a scream that almost could be heard through the newspaper. How do you think God feels about that?”

“COMMENT: Not being the mayor of Chicago, I am not authorized to speak in the name of God. But my personal opinion is that I’m tired of people talking about getting ‘behind’ this or that war policy, after they and theirs have stayed 8,000 miles ‘behind’ where the fighting is going on.”

See this week’s TCD1972 on June 22 for Mayor Daley’s speech at the mayor’s conference, which per the Associated Press swayed the conference’s vote on gun control and its resolution regarding the Vietnam War.

It’s correct that Daley exhorted the other mayors to support President Nixon, but his position was actually more nuanced—a word that admittedly is not typically used in association with Mayor Daley.

Daley advocated for a resolution asking for the war to end after an internationally-supervised ceasefire and a release of prisoners, rather than naming a specific withdrawal date, saying he felt they should support the president in foreign affairs. Daley’s full quote was:

“In the name of God, let us stand behind the President and hope and pray he can end it [the war] tomorrow.”

Regarding gun control, Daley persuaded Mayor Roman Gribbs of Detroit to strengthen his gun resolution. Gribbs’ resolution called for a national ban on handgun sales and possession except for police, military and “sportsmen’s clubs.”

“In caucus, Daley got him to expand the ban to include (a ban on) manufacturing and importation (of handguns) and add a clause calling for a national handgun registration law,” according to the Tribune’s Peter Negronida.

One more letter:

“W.C. ADAMS, Chicago: I read that a member of the state Legislature was caught driving 100 miles an hour on Route 66 twice in the same day, but the police couldn’t hold him because law says a legislator has some kind of immunity. Can that be true? Why should a politician be allowed to drive like a maniac?”

“COMMENT: It is true. The state Constitution provides that a legislator cannot be detained on his way to a session of the Legislature. It makes no sense to me. Considering the kinds of laws they pass, legislators should be seized at every opportunity.”

FYI, this is about State Rep. Michael Zlatnik (R-Chicago), who per a Chicago Tribune editorial was the subject of their “Action Express” column because he was caught on Route 66 doing 114 mph. in his Cadillac. Oddly, the originally “Action Express” simply cannot be called up from the Tribune archives, and the only mention in the Daily News seems to be a letter to the editor.

Anyway: There is indeed an “immunity clause” in the new Illinois constitution, though it doesn’t apparently protect Zlatnik entirely.

“Tho he was required to appear in court on the speeding charges, the police were not permitted to arrest him and take him into the station, as they surely would have done with some lesser mortal,” writes the Tribune editorial board.

The Tribune is not amused in general by politicians ignoring traffic laws:

“We have made numerous trips to Springfield by auto and can recall many occasions when, driving at the 70 mile-an-hour legal limit, we were passed by an endless succession of cars bearing legislative license plates which quickly disappeared into the distance.”

It’s off-topic, but the editorial also notes that State Sen. Charles Chew (D-Chicago) has “won the wrath of many a Springfield motorist by parking his Rolls-Royce in all manner of illegal places including, once, in the middle of a downtown sidewalk.”

As we here all know, weekends could be sad for a Daily News family because Mike Royko wasn’t in the Daily News’ single weekend edition. So we look for Mike elsewhere on weekends.

June 24-25, 1972

Mike is in the real Daily News weekend edition this week, via Bob Herguth’s page 5 column:

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Mike already trimmed the verbal fat, so he doesn’t need to be summarized Reader’s Digest-style, either. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, plus the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. You can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many iconic columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there’s riveting work covered here you will never read elsewhere.

If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career which includes a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

Do you dig spending some time in 1972? If you came to MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY from social media, you may not know it’s part of the book being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

To get MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY in your mailbox weekly along with THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 and new chapters of the book—

SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE!

Jack Reilly was a total asshole!

My dad was a cab driver & there was a jerk just standing in a crosswalk & not moving. So my dad honks at him.

A day later he's told he has to go & apologize to Reilly, who was the jerk in the crosswalk!