Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today: Eating blintzes at Ashkenaz

Weekly Compilation July 3-9, 1972

To access all site contents, click on the rose icon in the upper left corner or HERE.

Why do we run this separate item, Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today? Because Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the serialized novel central to this Substack, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” lived in a Daily News household. The Bertoluccis subscribed to the Daily News, and back then everybody read the paper, even kids. And if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko. Get your Royko fix on Twitter too— @RoselandChi1972.

July 3, 1972

This is my favorite Slats Grobnik column. It checks every Slats category—the sights and sounds of a 1930s-40s Chicago childhood, the Twain-like transcription of the Chicagoese, the wistful end, and of course the perfect sparely-written prose.

This column first appeared July 8, 1968, then slightly adjusted to run every Fourth. It originally started “It was early last Thursday morning and I heard a strange sound.”

You’ll find this column in Section One of your “Slats Grobnik and Some Other Friends,” which I assume you have beside you ready to reference, as befits the Bible that it is.

Just a few excerpts here for those who still need to purchase a copy:

“Every 4th of July morning, I hear the same strange sound. It is Slats Grobnik’s voice. He is in front of the house yelling: ‘Yoh-ho-hoooo-hoooo…can you come out?’

“He is out on the sidewalk and he has a big, brown paper bag in his arms. He points at it with a bony finger.

“He opens the bag. ‘Lookit,’ he hisses.

“‘Wow,’ I gasp.

“There are Zebras by the package, and cherry bombs, torpedoes and skyrockets, more Zebras, pinwheels and other great stuff.

“Wherejagettim,’ I hiss.

“‘Gynatruck cameroun’ sellnum,’ he hisses.”

And Mike and Slats are off to terrorize the neighborhood with their fireworks.

They use punks to light cherry bombs inside tin cans, they toss Zebra firecrackers into backyards, and they line up torpedoes on the streetcar tracks.

“At the end of the block, on the corner, all the guys are waiting. Slats’ brother, Fats; Big Head Louie; Sneaky Tony; Crazy Birdy. And they all have big, brown paper bags.

“We trot faster. But we don't get any closer. All the guys start fading away, disappearing. And Slats starts disappearing.

“It happens every 4th of July morning. And I’m awakened by the same sound. It’s the alarm clock. I listen for the ‘Yoh-ho-hoooo-hoooo…can you come out.’ Nothing.

“Ahhh, nuts.”

Don’t miss the Chicago History Rabbit Hole in the Weekend Edition, last item!

July 4, 1972

No paper at all, the whole Daily News went fishing—so no Mike!

If you dig Mike Royko, you’ll want to see the news he’s writing about. Check it out here!

July 5, 1972

“Jesse Jackson has suddenly emerged as one of the leaders of the Illinois delegation to the Democratic convention,” writes Mike. “He shows up on the network news shows with such frequency that he barely has time to change clothes six times a day.”

What the heck?

Background: Over in THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, we’ve followed as Ald. Bill Singer led a group of independent Democrats challenging the Cook County delegates to the Democratic National Convention who were elected in the primary. That includes Mayor Daley. Daley and his delegates—the “Daley 59”— were elected after being slated and backed by the Democratic Machine, in direct violation of the new reform rules the Democratic Party put in place for choosing delegates to the 1972 convention.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson became co-leader of the challenge just as Singer’s group got a Democratic Party hearing officer to come to Chicago, listen to both sides, and write a report recommending a decision to the Democratic National Convention’s Credentials Committee. At the hearing, Jackson had to admit under questioning by Daley’s lawyers that he hadn’t run in the primary for delegate himself, he hadn’t voted in the primary, he had just read those convention reform rules about a week earlier, and he didn’t know some of his co-defendants or his side’s lawyers.

Regardless, the hearing officer ruled across the board for the Singer-Jackson side, and the Credentials Committee voted to back the hearing officer.

Mayor Daley was dumped. He lost by three votes.

The U.S. Court of Appeals has just refused to overrule the Credentials Committee and reinstate Daley’s delegates. The Appeals court says the issue should be decided at the convention. That means…

But that will be next week.

See June 2 in THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 for a look at those hearings, see June 23 for Daley loyalists raiding the Singer-Jackson meetings to pick an alternate slate of delegates, and see Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today on June 26 for a look at young Richard M. Daley leading one of those meeting raids. See July 3 for Singer and Jackson’s initial reactions to winning their challenge, and July 5 for reaction after the Appeals Court decision.

Right now in our 1972 timeline, the alternate slate of delegates chosen by the Singer-Jackson challengers is set to be seated with the Illinois delegation at the 1972 Democratic National Convention.

Ald. Singer and Rev. Jackson are now the faces of Chicago’s Democratic delegation—not Mayor Daley, who has headed the Illinois delegation to the national convention every four years since 1958.

1958.

Back to Mike:

He notes that Mayor Daley’s delegates were dumped by the Credentials Committee for not following the reform rules on delegate selection. “The Jackson-Singer delegates didn’t follow the rules either,” he writes. “As far as I can tell, they became delegates by placing their hands upon each other’s heads, looking up at the sky, and declaring: ‘We are delegates.’ But they were accepted because they talk cleaner than Vito Marzullo.”

“Thus, Jackson became one of the year’s great political success stories.”

Two things to note here.

1)Ald. Marzullo led the Daley forces that disrupted the Singer-Jackson meeting to pick delegates in the 7th Congressional District. Besides telling the chairman “We will follow you to the graveyard,” Ald. Marzullo reportedly threw around quite a few F-bombs.

2) How did the Singer-Jackson caucus meetings choose those alternate delegates?

This was quite confusing. Mike’s description isn’t far off. So you know I’m not mixing it up myself in translation, let’s get it directly from Chicago Daily News political editor Charles Nicodemus on June 22:

Originally, the challengers had publicized plans to hold 48 “neighborhood caucuses” open to all Democrats, at which representatives were to be chosen for eight district conventions, where the final delegate selections would have been made.

But the challengers said Tuesday they were changing their selection method and would give only the unsuccessful nonorganization [non-Machine] delegate candidates from the March 31 primary the right to vote for the proposed alternative delegation.

Ald. William Singer (43d), a leader of the Chicago challengers, said each of the unsuccessful candidates, who range in number from 8 to 22, depending on the district involved, would be given a weighted vote proportionate to the number of votes he drew in the unsuccessful primary effort.

Each of the eight districts will elect all but one of the delegates it would normally be entitled to. Then on Saturday, the selected delegates will meet to pick eight ‘at large’ delegates.

So basically the only people who voted for the Singer-Jackson alternative slate of delegates are the people who lost when they ran against the delegates elected in the March 31 primary.

That scheme was described again by Nicodemus after the Singer-Jackson caucus meetings were held, and I saw no other news accounts claiming the voting method had been amended again.

However, you have to give the Singer-Jackson faction this: Without holding another real election at official polling places, which wasn’t going to happen, it’s hard to imagine how they could have chosen alternate delegates in a way that gave Democratic voters a say in the process.

It’s a pickle.

I wondered how progressives supporting the Singer-Jackson slate felt about that angle. I can’t go back and ask them in 1972, but I have been able so far to speak with legendary Chicago politico Don Rose and legendary UIC Prof. Dick Simpson, then Ald. Dick Simpson.

“I don't think the thought crossed my head,” says Don Rose today. “I was just against the Daley Machine.”

Prof./former Ald. Dick Simpson was more voluble on this point.

“Well, I had been involved in the McCarthy campaign for president in ‘68,” says Simpson, who helped organize and run the challenger caucus meetings. “At the convention, it was clear to me that the process was not a fair one. The Machine had too much strength because of patronage and favors and contracts. It was clearly the case that the Daley delegates were mostly ward committeeman, and the behavior of the Daley delegation at the ‘68 convention really didn't reflect the diversity of opinion. I suspect the majority of Democrats in Chicago would have supported either McCarthy or McGovern. Instead the division at the convention was 114 for Humphrey and four for McCarthy. So it was clear to me from personal experience that the Machine delegates were not a good representation of the views of Chicagoans. So I didn’t have much sympathy for the argument that they were legitimate delegates.”

Instead, Simpson adds, “I thought the critical thing was to challenge the regular Daley delegates, and many people like Ald. Singer were legitimate choices even though they had to be made at public meetings rather than the primary itself.”

More from Don Rose, Dick Simpson, and hopefully others in a post to come that will go deeper into the Chicago coverage of the delegate fight—which readers who have had enough can just skip.

Next up in the column, Mike remembers Jesse Jackson’s angry public comments immediately after the March 31 primary, particularly denouncing State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan for winning the Democratic nomination to run in the general election for a second term.

Hanrahan is indicted and about to stand trial (in our 1972 timeline) for conspiracy to obstruct the investigation into his office’s 1969 predawn police raid that killed Black Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark. Hanrahan is exceptionally unpopular in the Black community.

Mike says he became curious after Jackson’s public comments on the primary, so he went to City Hall to check the voting records and see if Jackson had voted.

“The records showed he had not,” Mike writes.

“That seemed strange because most people who dislike Hanrahan took the opportunity to vote for one of his opponents.”

Mike asked Jackson about his voting status, and “he provided a lengthy explanation….His explanation wasn’t as lame as a one-legged horse, but almost.”

“In accepting Jackson as a delegate—indeed, as a leader—the reform rules have achieved the ultimate generosity. They have given a voice to the person who doesn’t bother to vote,” writes Mike.

“That’s about as democratic a reform as I can think of, except maybe letting Republicans have a voice in the Democratic convention.”

Mike doesn’t think it sounds like a practical way to win elections.

“If they are going to open up the party to the person who doesn’t bother to vote, then they would be wise to also let in delegates like Vito Marzullo, who is capable of getting two votes out of one voter. That way, Marzullo could compensate for the Jackson-type non-voter.”

July 6, 1972

A somewhat unusual format for Mike, writing an open letter:

“Dear Ald. Singer,

“You are a spunky guy, Bill, and I like you. You served as a judge in my Penny Pitching Contest. There aren’t many aldermen I would have trusted with all those coins.

“I admire the way you stand up and tangle with the mayor at City Council meetings. In general, you are good, honest, true, as well as smart and energetic, although you could lose a few pounds.

“So I hate to tell you, but if I were a delegate in Miami Beach next Monday, I would vote to seat ‘Daley’s 59,’ not your 59.”

A shocking column on the surface—Mike Royko, author of “Boss,” backing the Machine?

Also, Mike Royko extolling a politician—any politician—with adjectives like “good, honest, true”?

I haven’t seen Mike write anything like that about any other politician except the legendary Sen. Paul Douglas—for whom Ald. Singer worked as a young man. If readers recall anything similar about another politician, please let me know.

It must have been very difficult for Singer to decide how he felt about this column. Who wouldn’t like to be lumped into the same category as Paul Douglas?

Mike writes that he doesn’t like the Machine delegates better— “most of Daley’s delegates would cheerfully string me up from a tree”— while Mike admires many of Singer’s 59: “Some are friends of mine.”

And he doesn’t support the Daley 59 simply because he thinks the Machine can hustle more votes in the general election “than your enthusiastic amateurs.”

It’s because Mike doesn’t see how the Singer-Jackson delegates represent Chicago Democrats, which is supposed to be the point of those delegate selection reform rules.

See the July 5 column coverage above for thoughts on this argument from legendary Chicago politico Don Rose and legendary UIC Prof/former Ald. Dick Simpson, neither of whom were impressed by the issue at all.

Mike acknowledges that the Singer-Jackson delegates represent women better—about half are women, versus only five of Daley’s 59. And, we should note, Daley added those women only recently by bumping some duly elected delegates, in a late and cursory nod to the reform rules he had flouted.

About a third of the Singer-Jackson delegates are black, Mike notes, many are young, and a few are in the parlance of the time “Latin-Americans.”

“But as I looked over the names of your delegates, I saw something peculiar. It might not be noticeable to somebody from another part of the country, but it jumps out at a native Chicagoan.”

There’s only one Italian, and only three Polish names in the Singer-Jackson delegation.

“Does that mean that only 5 per cent of Chicago’s voting Democrats are of Polish ancestry?” asks Mike.

“If that were true, a Republican would be mayor of Chicago.

“Your reforms have disenfranchised Chicago’s white ethnic Democrats, which is a strange reform.”

Now Mike gets to the nub of what is an unspoken early form of identity politics behind the Singer-Jackson calculus:

“Don’t tell me that it shouldn’t matter what a person’s ethnic background is. If it is important to a black that he has a black representative, which it is, then it matters to Uncle Stanley that a pierogi-eater be out in front for him.

“You can’t sit down and decide to have this many black delegates, that many women, this many Chicanos, that many young people, then almost ignore the existence of white ethnic groups.”

For Younger Readers, recall that this is 1972. U.S. immigration laws began throttling European numbers earlier in the 21st century, so that in 2022, relatively few European ethnic—aka “white”—voters in Chicago are first or second-generation immigrants. One can argue that in 2022, the “white ethnics” are largely assimilated into the larger population, more likely to identify themselves by socioeconomic class than their ancestral homeland. Not so in 1972 for middle-aged and older “white ethnic” Chicagoans—in other words, most “white ethnic” voters.

Mike points out that while Mayor Daley’s delegation is far from perfectly representative, “he does have 10 Poles, 7 Italians, 5 Jews, a scattering of WASPs, Germans, and those undefinable names known as ‘Americans,’ and 12 blacks.” So Daley has about 15% Black delegates, versus the Singer-Jackson slate’s 30%.

“While [Mayor Daley] doesn’t have a perfect balance either, his delegates come much closer to reflecting the people who vote as Democrats in Chicago than yours do,” writes Mike.

Which is no accident. Although Mike doesn’t get to it here, he has often mentioned, as in “Boss,” that the Machine’s original secret sauce was precisely what the Democratic Convention’s reform rules for delegates call for—reflecting the population demographics.

The secret sauce was invented by Anton Cermak.

“Cermak had the gall to challenge the traditional South Side Irish domination of the Democratic Party,” Mike wrote in “Boss.” “More than gall, he had the sense to count up all the Irish vote, then he counted all the Italians, Jews, Germans, Poles, and Bohemians. The minority Irish domination didn’t make sense to him. He organized a city-wide saloon keepers’ league, dedicated to fighting closing laws and prohibition. With the saloon keepers behind him, he couldn’t be stopped. He became president of the Cook County Board, took over the party machinery, and ran for mayor in 1931.”

And he won. Cermak may have continued as mayor indefinitely, thanks to the new Machine, had he not been next to newly-elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt when an assassin fired at FDR and missed.

“By creating the ethnically balanced ticket, something new, [Cermak] put together the most powerful political machine in Chicago history,” Mike concluded in “Boss.”

It’s ironic that the Machine was born by representing the population by identity, and in 1972 it’s being challenged because it didn’t extend that identity representation well enough to women, Blacks, and Latinos.

In today’s lingo, Mike is essentially pointing out the further irony that the Singer-Jackson challengers have erased the identities of working-class European ethnics who were first represented in government via the Machine a little over 40 years earlier, lumping them into the category of “white” and presuming they are thus represented by any middle or upper middle class, college-educated Singer-Jackson delegate with light skin.

In today’s letter to Ald. Singer, Mike also objects to the fact that half or more of the Singer-Jackson delegates ran in the primary election, and “got stomped.” Others, like Jesse Jackson, didn’t even run in the primary—and as noted, Jackson didn’t even vote.

“Now they are delegates, having been declared so by themselves, at meetings that were about as open as the Harvard Club,” writes Mike.

“In closing, Bill, forget what I said earlier about losing a few pounds.

“Anybody who would reform Chicago’s Democratic Party by dropping the white ethnic, would probably begin a diet by shooting himself in the stomach.”

July 7, 1972

“Idelle Goode, ace precinct captain, City Hall patronage worker, widow, and one of the loudest voices in Rogers Park, was so mad she couldn’t eat her blintz.

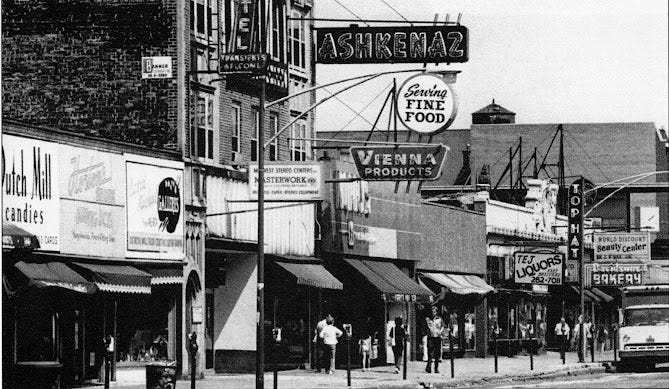

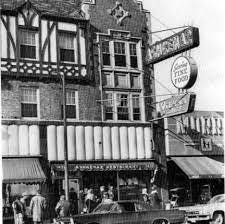

“Every time she’d take a bite, she’d think of another outrage that had been committed against her and her voice would ring out across the famous Ashkenaz Restaurant and Delicatessen, on Morse near the L.

“‘Those creeps,’ Idelle yelled. ‘Who in the hell are they? We never heard of them before.’”

She’s talking of course about the independent Democrats led by Ald. Bill Singer and Rev. Jesse Jackson, who have successfully replaced the 59 Cook County delegates elected in the March 31 primary to attend the Democratic National Convention—at least until a floor fight vote at the convention itself next week.

“I got 506 registered voters in my precinct,” Idelle Good tells Mike. “I brought out 420 of them. And I got 401 votes for our candidates. I carried for (Paul) Simon, I carried for Berg, and I carried for Seymour Simon and the other delegates.”

Note: Ald. Seymour Simon, former Machine loyalist turned independent, is in the strange position of having been elected on the Machine slate of delegates, even though he supports the Singer-Jackson challenge. In fact, Ald. Simon presented some of the most damning evidence against the Daley Machine slate at the hearings before the Democratic Party hearing officer.

“You think I had to tell my people to vote for Seymour Simon instead of some creeps they never heard of?” says Idelle Goode, meaning the independent Democrats who ran for delegate positions in the primary election, who are now the Singer-Jackson challengers. “Sure I told them to, but I didn’t have to. They know who Seymour Simon is. Everybody knows him.”

Idelle doesn’t directly answer Mike when he asks whether she maybe pulled some common Machine precinct captain tricks, like “helping an aged finger on the preferred lever”. Instead: “I don’t use no dead people,” she repeats several times, ending with:

“And if those others want to be delegates, let them win it fair and square. But they couldn’t do it. So now they cheated. Those creeps got 19 votes in my precinct and I got 401, and they say they’re the delegates.”

But Idelle Goode has news for the Singer-Jackson Democrats: She will show her voters how to split their general election ticket, voting for Machine Democrats in the city, county and state, but voting for President Nixon at the top of the ticket. And she plans to meet with other precinct captains, who she believes will do the same thing.

“It’s a wry form of justice, in a way, because the Machine’s captains have pulled every cheap trick in the book in election after election to have their way,” writes Mike. “Now they know how it feels to be on the other end.

“And the sight of Mayor Daley’s 59 whining about being pushed aside has its satisfactions. They set an all-time record for pushing people around in 1968. They won’t really know how it feels until they are hit on the head.”

However, Mike points out, Chicago has 3,200 precincts, with a lot of Idelle Goodes. The likely nominee at the upcoming Democratic National Convention, Sen. George McGovern, and his people “remember that in 1960, John F. Kennedy carried Illinois by a mere 10,000 votes. If the Idelle Goodes of Chicago were mad at him, he wouldn’t have even come close.”

The Chicago Machine, Mike concludes, “still has enough Idelle Goodes around to make McGovern wish Bill Singer and Jesse Jackson would just go away.”

As we here all know, weekends could be sad for a Daily News family because Mike Royko wasn’t in the Daily News’ single weekend edition. So we look for Mike elsewhere on weekends.

CHICAGO HISTORY RABBIT HOLE:

Blintzes at Ashkenaz

Did you wonder about the Ashkenaz Restaurant on Morse, where Mike met precinct captain Idelle Goode for his Friday, July 7 column?

I sure did, because this is not typical Royko style—naming a specific restaurant to add some atmosphere. Mike usually names such places more generally, and leaves it at that.

A perfect example came up on April 11 with another Jewish restaurant, when Mike wrote a column about the dispute between author Harry Barnard and restauranteur Lenny Minck over the price of potato pancakes.

Rather than telling us precisely where Harry Barnard paid the outrageous price of $1.65 for four potato pancakes, Mike simply wrote that Lenny Minck owned “several” restaurants in the Loop. To discuss the column, I explored where all the Minck’s restaurants once flourished, and suggested we imagine that Barnard nipped into the Minck’s at 75 E. Wacker and looked at the Sun-Times Building across the river as he ate.

So I love that Mike tells us that Idelle Goode ate blintzes at the Ashkenaz Restaurant and Delicatessen on Morse, near the L.

Ashkenaz is a storied Chicago restaurant indeed.

There’s a terrific look at the Ashkenaz Restaurant on Morse on the website of the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal from 2017, compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D. Dr. Gale has put together several pictures of West Morse with the Ashkenaz, including the one above, plus pictures of the food you would order if only you could still go there, from kishkes in brown sauce, kugel and latkes, to chicken soup with kreplach. Don’t read on an empty stomach.

Also: Stayed tuned for the end of this item, because the Tribune’s legendary Ron Grossman gets the last word on Ashkenaz.

In an encyclopedic look at 1970 Jewish food companies and delis in the Tribune, Martin Savela gave a virtual tour of Ashkenaz:

“As you enter, there is a long delicatessen counter on the right filled with trays of amber smoked chubs, chopped chicken livers, potato salad, perogen (small baked pastries filled with chopped chicken livers and onion, etc.), gefilte fish, kishkes, and pickles,” wrote Savela. “Gleaming red Vienna salamis hung from a rack on the wall.

“One wall of the restaurant is somber brown; the other is a mosaic of green, blue, and yellow tiles, an imitation ─ intentional or not ─ of the colors used by Marc Chagall in his evocative paintings of Jewish life in the villages of old Russia.

“Beyond the counter in front is an open kitchen manned by four cooks, who prepare short orders and sandwiches. There are three waitresses.” Past the counter, through an archway, was the dining room, with the “tone…of a family gathering.”

The menu, wrote Savela, included over 100 dishes and 35 dinners.

Attorney Ed Mogul gave another timeless description of Ashkenaz in the Tribune in 2002:

“The high point for family socializing in the '50s would be to go to Ashkenaz during the heat and mugginess of the summer. We would line up outside, just waiting to get inside and be in the cool of their air conditioning... (Inside) you had to wait in line against the wall. But you were already being treated to the smells and sounds of all the activity. Ashkenaz was our Moulin Rouge.”

Daily News reporter Diane Monk visited Ashkenaz in 1969 and reported that it opened seven days a week at 5 a.m. and stayed open until 1 a.m—except Sundays, when it closed at 2 a.m.

Ashkenaz was at 1432 W. Morse, just down the block from the first Minck’s at 1412 W. Morse.

Charles Percy, who’s an Illinois U.S. Senator in our 1972 timeline, grew up near Ashkenaz at 1645 W. Pratt. Here he is campaigning for Illinois governor in 1964, chomping down hard on an Ashkenaz corned beef sandwich.

Ashkenaz was “still the acknowledged focal point of the neighborhood” in 1973, soon after Idelle Goode ate blintzes while bitching to Mike Royko about Bill Singer and Jesse Jackson. That year, future Reader editor and co-owner Michael Lenehan wrote a lengthy profile of the Morse Avenue business district for the Daily News. He examined a neighborhood in flux, as the Jewish residents aged and young Chicagoans discovered the area.

Midwest Stereo Center had just moved from a small space down the street to a new, big quarters next door to Ashkenaz, Lenehan wrote. The store window next to Ashkenaz then displayed “prominently the names of modern youth heroes: Alice Cooper, Carole King, Elton John.”

Inside Ashkenaz, old-timers sat in gab sessions morning to night at the counter or standing outside its doors, wrote Lenehan.

“The place bustles literally from opening to closing, serving the community’s social needs as well as its physical cravings—it is obviously the clearinghouse for news of the neighborhood and information on old friends.”

There are slightly different versions floating around the internet and in newspapers regarding the exact beginning of the Ashkenaz Restaurant, how long it stayed on Morse, and where it went afterward.

George and Ida Ashkenaz started the restaurant in either 1910 or 1915, and son Sam Ashkenaz became the face of the restaurant by the 1960s. Some sources say the first Ashkenaz was on Maxwell Street, including a 1990 Sun-Times article on Hanukkah food focusing on grandson Steve Ashkenaz, who was then the chef at the Carnegie Deli location at 900 N. Michigan.

But Martin Savela, who interviewed son Sam Ashkenaz for his detailed 1970 story, reported that George and Ada immigrated from Russia and opened their business near the corner of Roosevelt and Karlov, which is North Lawndale.

Although Savela reports Mrs. Ashkenaz’s name as Ada—it’s “Ida” everywhere else, including her official obituary—we’ll go with Savela’s description a bit further:

“When the Jewish population moved north and west into the suburbs, the Ashkenaz family moved to Rogers Park, opening their first deli on Morse Avenue. It was a small shop, 10 by 30 feet or so, in which Ada Ashkenaz did the cooking in a tiny kitchen at the rear. During the mid-’30s they acquired the present space and opened a new restaurant. It burned in 1939, and the couple had no insurance.

“Sam Ashkenaz, who graduated from Purdue that year with a degree in electrical engineering, joined his parents to help recoup the loss, borrowed money from the restaurant’s suppliers, and has been in the business ever since.”

Some sources name Dorothy or Hy Kalmin as co-owners. From obituaries, we can see that Dorothy Kalmin was Sam’s sister, so Dorothy and Hy probably worked at the restaurant too.

In 1942, Ashkenaz placed some ads in in a brand-new paper, the Chicago Sun, looking for help.

Alas, Ashkenaz left the Morse location some time in 1976.

A short-lived location opened at 3223 W. Lake, and another location at 12 E. Cedar operated from about 1978 until 2012. Those locations are always mentioned in newspapers as belonging to a corporation, though. It’s unclear if the Ashkenaz family ever owned either spot. But the Cedar location was open long enough—almost 35 years—to be called a “neighborhood staple.” It was so well known that, strangely, New York Magazine of all places noted its passing in 2012. Michael Gebert wrote:

A Jewish resident of the Gold Coast we knew once told us that the first two calls you make when someone dies are to the next of kin, and to Ashkenaz for a deli tray for shiva. That suggests both the overlooked deli’s importance to its neighborhood… and why it closed Sunday, as its core clientele increasingly passed away.

“I thought the Rush Street version too tame,” says the Tribune’s legendary Ron Grossman, a connoisseur of Jewish cuisine, having grown up in Albany Park. “Customers weren't insulted. Part of the joy of a real deli.”

Though there are different versions of why and how Sam Ashkenaz left the Morse location, I can see for sure that he purposely moved the restaurant directly to the then brand-new Northbrook Court. That news made the Daily News Beeline column in December 1975:

In fact, the once humble neighborhood Jewish restaurant was considered a real draw both by Northbrook Court, and by what would be one of its more high profile tenants:

After Ashkenaz left 1412 W. Morse, a place called “Ashkey’s” replaced it, also serving Jewish deli food—apparently run by new people pirating the old name. A fire destroyed the building in 1978, putting an end to Ashkey’s, whoever owned it.

But how long did Ashkenaz last at Northbrook Court? The trail abruptly ends in newspapers and on the internet. I have no idea. Probably not long, since several people I know from that area only dimly remember that Ashkenaz was ever there. Sam Ashkenaz’s son, Steve, was working at the local Carnegie Deli by 1990, and briefly at another deli that made the paper in 1989. Presumably, Steve would have been at the family business if it were still around, so we can guess that Sam Ashkenaz’s restaurant in Northbrook Court lasted about ten years or less.

But those are cold facts, and what made a place like Ashkenaz great was the warmth—of the people and the food.

So let’s dig into more of that warmth—starting with comedian Shecky Greene, a once-famous son of the neighborhood.

Ashkenaz had a sandwich named after Shecky Greene, who Younger Readers will not know. But in mid-20th century America, Shecky Greene was famous enough to appear regularly on Johnny Carson’s “Tonight Show.” And that was a pinnacle of mid-20th century America. Winning an Oscar would be arguably better—but nobody won an Oscar without also appearing on Johnny Carson.

Shecky Greene grew up near Ashkenaz, which explains why he often gave the restaurant a shout-out:

“He mentions the Ashkenaz Restaurant to prove he's a hip Chicagoan,” wrote the Tribune’s Will Leonard in his “On the Town” society column in 1959, apparently unaware that Shecky Greene was from the neighborhood.

Fun fact: Don Rose’s wife went to Sullivan High School along with classmate Shecky Greenfield.

Eleven years later, Will Leonard reviewed Shecky Greene’s show at the Mill Run theater in Niles: “He told how he ruined the Johnny Carson show by coming up with stupid answers to Johnny’s stupid questions….He got in the usual plugs for the Ashkenaz delicatessen and the Hoe Kow restaurant. He tore off his coat and tie, and his shirt came out of his trousers. All traditional, and all screamingly funny.”

By the way, if you’re assuming Shecky Greene is an old-fashioned hack, I’ll note that one blog is absolutely adamant that Shecky Greene was years ahead of his time, an experimental comedian.

Per that blog, Ed Sullivan once yelled at Shecky Greene: “You dirty Jew sunofabitch, you're sicker than Lenny Bruce!”

At first I assumed that quote wasn’t true, but I didn’t care because it’s hilarious. Then I watched the Shecky Greene clip above, heard him start his act with a pretty vicious Ed Sullivan imitation, and thought, “Who knows?”

We know the true nature of Shecky Greene’s attachment to Ashkenaz, and of the Shecky Greene sandwich, because long-time New York Times sports writer Ira Berkow is also a native of the Morse Avenue neighborhood, and wrote about it for the Tribune.

“The sandwich named in [Shecky Greene’s] honor at popular Ashkenaz was the neighborhood's ultimate tribute to a local boy made good,” wrote Berkow. “The sandwich consisted of a double decker of corned beef and egg, lettuce tomato and with a generous dollop of potato salad spilling off the plate. That and the barbecue beef sandwich with the special Ashkenaz hot sauce that made you cross-eyed with the first taste were favorites of mine in high school in the mid-1950s.”

Berkow also wrote a wonderfully evocative peon to his West Rogers Park years for “Neighborhoods Within Neighborhoods: Twentieth Century Life on Chicago’s Far North Side,” a book by Neal Samors and Michael Williams with Mary Jo Doyle, published by the Rogers Park/West Ridge Historical Society in 2002 and excerpted in the Tribune and Sun-Times.

The aromas and taste of Ashkenaz acted as Berkow’s madeleines to summon up his old neighborhood.

Forty years after he left Chicago, Berkow wrote, “I’ve never gotten the Ashkenaz out of my taste buds. Besides being one of the great eateries of Western civilization, Ashkenaz was a gathering place for the kids after school, and particularly on Friday nights following a movie, usually at the Granada….Alas, Ashkenaz is gone now, torn down, not a brick or pickled herring left….It ought to have been named a national landmark and preserved, like the log cabin Lincoln was born in, for example, Instead, a parking lot—a parking lot!—exists where Ashkenaz once proudly and aromatically stood.”

Just ten years into his post-Chicago life as a young man making his way in New York, Berkow heard in 1975 that ABC’s Barbara Walters was visiting the top ethnic restaurants in the country for her then-current TV show, “Not For Women Only.” For Jewish cooking, Walters’ show had chosen Ashkenaz. Berkow tuned in to watch:

“The beloved and no-nonsense proprietor, the balding, 61-year-old Sam Ashkenaz himself, with glasses gleaming under the TV lights and natty in tied and clean white apron, wowed them by whipping up his stupendous, succulent and, yes, beautiful ‘Ashkenaz Cheese Blintz Treat,’ topped, naturally, with fresh blueberries”.

“I will never forget the motto printed on the check you were handed at Ashkenaz,” Berkow wrote. “It read: ‘Better than this there isn’t!’”

I sure wish we had an Ashkenaz check to include here.

Let’s give the Tribune’s Ron Grossman the last word on Ashkenaz, and a great last word it is:

“Rogers Park was a step and a half from where we lived in Albany Park. But when a buddy had a car we'd motor up that way and it was a place to stop. It was larger than the delis of my neighborhood but the inhabitants were roughly the same. For the price of a coffee, you could get an argument on any subject under the sun. Heartburn came with a sandwich, with no extra charge

“Countermen who doubled as philosophers. How could they not? One customer would demand: ‘No fat on the cornbeef.’ Another would say: ‘Leave a little fat. My Tzonl likes it that way. Did I tell you? He got into med school! Baruch HaShem. Maybe also a half sour pickle. And my daughter...’

“The tables would be filled with local sharpies. Twirling the keys to a car presumably outside, but who knew? They'd be swapping stories about surefire getting rich games. But when the check came each would defer to the other saying, 'Oh, I just don't have any money with me, I'll catch you next time.’

“The waitresses were blonde buxom and inured to the constant chirping: 'Sweetie, how about another cuppa?'

“I remember the shock when Ashkenaz closed. It already happened to the delis in my neighborhood. But that one seemed to be a forever thing.

“I guess the lesson is nothing is forever, even a classic deli."

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Mike already trimmed the verbal fat, so he doesn’t need to be summarized Reader’s Digest-style, either. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, plus the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. You can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many iconic columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there’s riveting work covered here you will never read elsewhere.

If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career which includes a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

Do you dig spending some time in 1972? If you came to MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY from social media, you may not know it’s part of the book being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

To get MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY in your mailbox weekly along with THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 and new chapters of the book—

SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE!