Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today: Marbles, pitching pennies & Morris B. Sachs

May 8-14, 1972

To access all site contents, click on the rose icon in the upper left corner or HERE.

Why do we run this separate item, Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today? Because Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the serialized novel central to this Substack, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” lived in a Daily News household. The Bertoluccis subscribed to the Daily News, and back then everybody read the paper, even kids. And if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko. Read the daily Royko briefing Monday-Friday on Twitter, @RoselandChi1972.

First:

Don’t miss the deep dive in Mike’s last column this week.

Now we return to our regularly scheduled Mike Royko coverage.

In 1972, this was one of those weeks when Royko readers didn’t get a fresh fix because Mike went on vacation. But this time the Daily News took pity on readers:

As real-time Royko readers know, sometimes when Mike was off, all you got was an announcement, not even leftovers from the fridge. Now those were tough weeks. This is a lucky week! Pull up a chair and dig in.

May 8, 1972

Mike doesn’t understand why he sees no kids playing marbles since warm weather arrived in Chicago.

“Maybe it’s because nobody plays marbles on TV,” he theorizes. “Most of the games youngsters play have been popularized on TV. Golf, bowling and sex, for example.”

Mike doesn’t miss playing marbles, because he wasn’t very good at it—and “nobody in the neighborhood was in the same class as Slats Grobnik.”

Slats was born with a natural athletic gift, like Wilt Chamberlain’s height and Ted Williams’ eyesight. “Nobody had a thumb as long as Slats’. Nobody had fingers as long as Slats’ thumb. And it was powerful. He was constantly exercising it, sitting for hours every night, just flicking it.”

The alderman heard and got excited, hoping Slats would win the city-wide marble contest they used to hold back then.

“The alderman went to Slats’ house and promised his parents that if Slats won he would have a city job some day. Slats cried hysterically until his mother explained that he wouldn’t really have to work.”

Younger Readers may have no idea how the classic game of marbles was played. Here’s a YouTube video that seems basically correct, though it suffers from having the kids play marbles inside. Really? They couldn’t find a sidewalk?

May 9, 1972

Odd that the paper didn’t run this rerun on Friday, since it’s about Friday the 13th.

“This is the dark day—Friday the 13th—when we must all beware of such unlucky happenings as our paths being crossed by an alderman.”

Savor the lede, as always.

“There was nobody more superstitious than Slats,” writes Mike as a prelude to describing a series of bad Friday the 13ths that haunted Slats over the years.

“He tried to ward off the day’s bad luck by getting good luck charms from his Aunt Wanda Grobnik, who was famous for her ability to read tea leaves, coffee grounds and to look into the future. Her powers as a seer were such that she could look at Slats when he was only a year old and say: ‘He’ll grow up to be a bum.’ Even Slats later said she was accurate.”

May 10, 1972

Mike has heard that Arlington Heights police “are said to have put some kind of ban on the playing of sidewalk hopscotch.”

That’s unenforceable, he writes.

“It would be a violation of an unwritten common law that says sidewalks belong to kids.”

Basically, “sidewalks are really long, narrow playgrounds.”

Slat Grobnik lived on sidewalks, and wouldn’t even go to nearby Humboldt Park with Mike and their pals. Slats’ feet would blister if he walked on grass too long.

Whatever Slats did all summer, he did it on the sidewalk.

“One summer, he spent all of July pitching pennies. He got so good that one Sunday morning he made 14 straight liners. The precinct captain had that penny bronzed and and it was hung up behind the bar of the corner tavern. Later, Slats’ mother put it in with his bronzed baby shoes and his first tooth, a one-inch molar, incidentally.”

Younger Readers, you may have played marbles, but you almost certainly did not pitch pennies. Mike Royko held an official penny-pitching tournament once in the Sun-Times/Daily News parking lot. According to Wikipedia, the game was played by Ancient Greek kids with their Ancient Greek coins.

Browsing around, I came up with the perfect description of pitching pennies, from a heartwarming website created by a bunch of friends who grew up around Imlay Park in the far Northwest Side neighborhood of Norwood Park.

Here’s the screenshot, with clear instructions, glossary of terms and even an annotated picture. This is not how Ancient Greek kids played—the typical description of penny pitching has players throwing their pennies at a wall, and seeing who can toss their penny closest. But Mike speaks of “liners,” so we know this is the form of penny-pitching played by his pals near Humboldt Park.

May 11, 1972

These days, kids get arrested at protests all the time. But that doesn’t mean youth of the past weren’t interested in “the grave issues of their time”.

“All during his boyhood my friend Slats Grobnik brooded about the national debt,” writes Mike.

“Nobody says much about it anymore, but the national debt used to be of great concern to everybody, especially Republican politicians and the Tribune. In his editorials, Col. McCormick always sounded like he was going to be stuck with the whole tab, plus tip.”

Mike loves to stick it to the Tribune whenever he sees a chance.

Slats became alarmed as a child about the national debt, after hearing on the radio one day how much each man, woman and child would have to pony up to pay it off.

“Slat was most bothered when the Republicans would warn that if the national debt wasn’t paid, the burden would pass to the next generation.

“One night at dinner he called his father a deadbeat for welshing on his share of the national debt and sticking Slats with it. Mr. Grobnik was so impressed by Slats’ precocity that he struck him on the head with a soup spoon…

“He took to leaving anonymous notes to his father in the mailbox. They said things like: ‘Your share of the national debt is $897. You know what happens to deadbeats.”

If you dig Mike Royko, you’ll want to see the news he’s writing about. Check it out here!

May 12, 1972

“The first time Slats Grobnik cracked one of his knuckles, dogs all over the neighborhood began barking, and a squad car came by to see who had been shot. Slats knew then that he had a special gift.”

When Slats cracked all his knuckles at once, they sounded “like a string of Zebra fire-crackers.”

“He once appeared on the Morris B. Sachs Radio Amateur Hour, cracking his knuckles in time to ‘Lady of Spain I Adore You.’ He did well, too, finishing in the judging behind a boy who clicked his teeth to ‘Lady of Spain I Adore You’ and a girl who toe-danced while playing ‘Lady of Spain I Adore You’ on her accordion.”

Three things here we must cover: “Lady of Spain I Adore You,” accordions, and the Morris B. Sachs Radio Amateur Hour.

“Lady of Spain”

“Lady of Spain” is the go-to popular song from the early years of the 20th century meant to signify a corny popular song you couldn’t get away from. When you google “Lady of Spain,” the first two pages of hits claim the song was written by mid-century singer Eddie Fisher, now best known for marrying Debbie Reynolds and fathering Princess Leia, aka Carrie Fisher, then dumping his family for one of Debbie Reynolds’ best friends—possibly even bigger movie star Elizabeth Taylor. But the video below focuses on 1931 sheet music for the song, which says “Lyrics by Erell Reaves” and “Music by Tolchard Evans,” who appear to be the correct authors.

This video is a great introduction to “Lady of Spain” because it’s played and sung by someone who sounds like a very modestly talented relative playing the piano at a family party. One of the comments on this video is “DON’T EVER PLAY ‘LADY OF SPAIN’ AGAIN!!” Yes; that’s perfect.

Reader James Costello sent the following hilarious link which explains the YouTube comment for the first link above—and gives us an excuse to watch Paul Newman. Thanks, James!

And to really be complete, here’s the popular Eddie Fisher version too, sung over a wedding picture of Eddie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds and then a string of Fisher photos. You won’t believe two of the biggest stars of the 1950s fell for this schmuck.

Accordions

Accordions were the early to mid-20th century instrumental equivalent of “Lady of Spain.” They were seemingly everywhere. Here’s a picture of Steve’s dad’s accordion school class in 1947, from Bortoli’s Accordion School in Roseland, which conveys the mid-century power of the accordion far better than words ever could.

Morris B. Sachs

Mike’s description of Slats’ appearance on the Morris B. Sachs Amateur Hour was perfect and prescient, as seen by its staying power.

In 1985, well over ten years later, Bob Hughes wrote a “Way We Were” article for the Tribune on Morris B. Sachs. Second graph:

“In the minds of many, the radio program--later a TV show--consisted mainly of an adolescent accordion player performing "Lady of Spain" with dizzying speed and flourishes.”

First came the stores

Morris B. Sachs came to Chicago an orphaned, penniless Lithuanian Jewish immigrant in 1908 or 1910, at either ten or 13 years old, depending on what source you go with. Newspapers say Morris moved in with relatives in Chicago, but a terrific account by Richard Reeder in the Winter 2014 Chicago Jewish History says nobody met Sachs at Ellis Island.

“Seemingly abandoned and unprotected, the boy was taken under the wing of a concerned stranger, a local butcher, who sheltered him at his shop, letting him sleep in a spot near the freezer,” writes Reeder. “This demonstration of kindness from a stranger was an example that stayed with Sachs his entire life. How the young Lithuanian Jewish boy found his way to Chicago remains a mystery.”

The papers say Sachs peddled clothes door-to-door in Back of the Yards, while Reeder has him starting in Maxwell Street Market, which makes obvious sense. Either way, the young Sachs saved his money, working up to a horse and wagon before opening his first Morris B. Sachs clothing store in either 1916 (newspaper accounts) or 1919 (Richard Reeder) at 6638 S. Halsted. Reeder writes that Sachs added three stories to the original building in 1940 and lighted signs: “Morris B. Sachs” and “CREDIT WITH A SMILE.” That store, once a mainstay of the mighty Englewood shopping district though not as famous as the Sears closer to the 63rd/Halsted intersection, is now a vacant lot.

The second Morris B. Sachs store opened in 1947 at 3400 W. Diversey, the intersection of Milwaukee, Diversey and Kimball. According to the Tribune’s coverage, 75,000-100,000 people “packed the intersection” for the official opening on the night of October 3. Chicago Mayor Martin Kennelly cut a ribbon to officially open the store.

“Stars of the stage, screen and radio provided entertainment,” wrote the Trib without thinking to name a single one. “Thousands of visitors inspected the new Sachs store which has been described as perhaps the most modern of post-war stores.”

Here’s the Milwaukee/Diversey/Kimball intersection in its latest shot circa 2022 on Google Streetview. The former Goldblatt’s in the center background is now a Gap at ground level. The building on the far left in the 1950 shot, with the sign for “Imperial Credit Co,” is replaced by an unremarkable two-story building for Bank of America, set farther back on its site, so you can’t really see it. A four-story red brick building is now visible farther back on the left. On the right, the drugstore building between Sachs and Goldblatt’s in 1950 is still there, now housing a Footlocker in the corner street space.

The Diversey/Milwaukee/Kimball Morris B. Sachs store closed by the mid ‘60s and sat vacant for 20 years before being bought and redeveloped by the city. It now houses the Hairpin Arts Center, a community arts center named in honor of Sol Goldberg, the building’s original owner, who made his money with a distinctive metal hairpin. Designed by the firm of Leichenko and Esser in 1930, the building is part of the Milwaukee-Diversey-Kimball Landmark District.

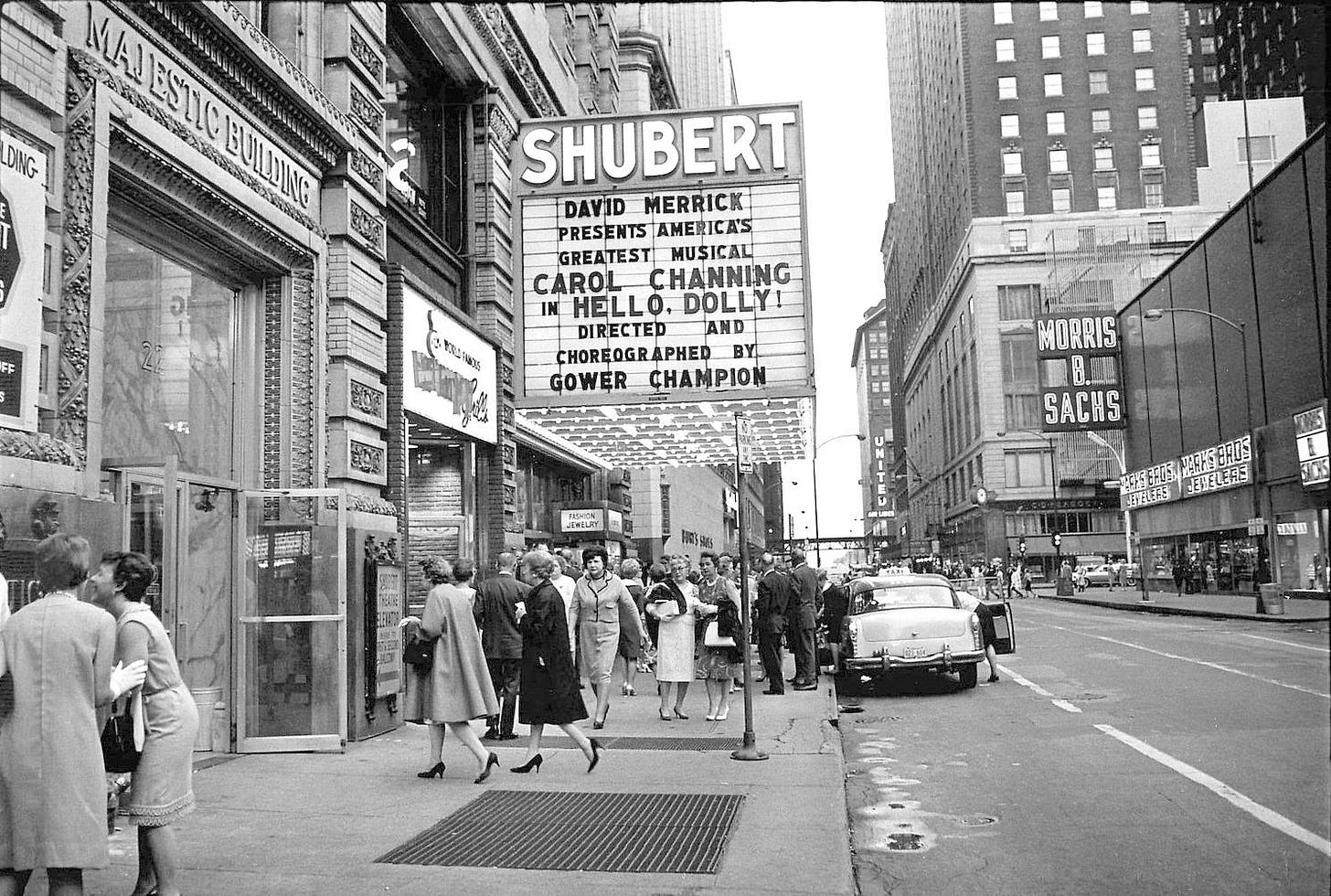

In 1957, Sachs opened a Loop store at State and Monroe. Here’s a 1966 view looking east on Monroe toward State, with the Schubert marquee in the foreground.

Here’s a similar view from the latest Google Streetview. That’s a Capital One Cafe on the ground floor in the building that formerly housed the Morris B. Sachs store on the right.

The Show

Everyone knew Morris B. Sachs’ name from his stores, but they also knew his face from the Morris B. Sachs Amateur Hour. The show started on Friday nights in 1934, broadcast on radio from the window of his first store at 6638 S. Halsted. Sachs moved the show to the Merchandise Mart when police complained about traffic jams. Soon Sachs rented the Civic Opera House every couple of months to accommodate the huge demand for tickets, switching the show to Sunday afternoons and hiring slick announcers to host.

The Morris B. Sachs Amateur Hour shifted to the new medium of television in 1949 on Chicago’s first TV station, WBKB, which later became WLS. The show jumped to WGN at some point, but I couldn’t tell precisely when that happened. WGN began broadcasting in 1948, the second Chicago TV station to spring into existence.

The Morris B. Sachs Amateur Hour helped launch careers for several stars, including Mel Torme. According to Richard Reeder, listeners/viewers phoned in their votes to name a winner. If you search “Morris B. Sachs” in the post-1985 Tribune archives, the name comes up continually in obituaries—for people whose relatives include mention of their loved one’s Amateur Hour wins. As Ronald Subeck’s survivors noted in 2020, “His obituary would not be complete without noting that he was a winner on the Morris B. Sachs Amateur Hour for his celebrity impressions as a teenager, one of the most thrilling moments of his early life.”

In 1955, as Morris B. Sachs began a run for Chicago city treasurer—oh yes, we’ll get to that next—Sachs told the Trib that while he peddled clothes as an orphaned immigrant on the South Side, he dreamed of Hollywood. “There was no chance,” he said. “There was no one to listen.”

As a teenager, Sachs almost went to Hollywood for acting school—but it cost $75. “I was lucky I didn’t have the money,” said Sachs. “Now I do my acting in the clothing business.” But Sachs said he promised himself that “if I made good, I would help people develop their talent.”

“He rarely misses an appearance on his own show,” noted the 1955 Tribune article. “Winners are given their prizes [a watch and $20 to $75] and then they shake hands with him and say a small speech, something like, ‘I want to thank Mr. Sachs for the opportunity to be on the show and all the wonderful people who voted for me.’” Morris Sachs insisted that none of the participants were coached to say that, and it’s probably true.

Of course, the Morris B. Sachs Amateur Hour was something of a publicity success for the Morris B. Sachs clothing stores. Plus, in 1955, it meant Morris B. Sachs had a face immediately familiar to voters when he went into politics.

The politics

Sachs ran for city treasurer in 1955 on a ticket with Chicago Mayor Martin Kennelly, who was running for re-election. Kennelly had been brought in by the Democratic Machine as a controllable reform mayor to spruce up the party’s image after too many scandals in Mayor Ed Kelly’s administration, even for Chicago.

Even though Kennelly was the incumbent two-term mayor in 1955, he didn’t get the Machine’s endorsement for that year’s primary. That went to the chairman of the Chicago Democratic Party—one Richard J. Daley, who beat Kennelly in the primary and went on to his first term as mayor.

But first, in the primary, Daley quickly needed to replace his own candidate for city clerk, Ald. Benjamin Becker (40th). Becker was accused of representing clients in zoning cases that he voted on in City Council. The more things change, right? Soon-to-be Mayor Daley picked popular, recognizable Morris B. Sachs to replace the errant Becker, even switching the ticket around so Sachs could still run for city treasurer. John Marcin, the guy who was running for treasurer, switched to city clerk to accommodate the change—as Tommy Henry would say on Chicago History Podcast, “because Chicago.”

The Democratic party’s Central Committee members met as usual at their Morrison Hotel headquarters and voted 46-0 to slate Morris B. Sachs for city treasurer.

Kennelly and Sachs’ other former political allies were furious, and Sachs took a beating in the press. The Tribune absolutely reamed Sachs in this March 12, 1955 editorial:

We don’t like to see a good man make a fool of himself and that’s just what Mr. Sachs has done by accepting the Democratic organization’s offer. He entered politics only a few weeks ago as the sworn enemy of the very men who have now wooed and won him. Apparently he is unaware that they don’t give a hoot for him but have picked him up in the hope that he can add a touch of respectability to a ticket that is in need of it….

We can assure Mr. Sachs that the gentlemen at the Morrison hotel do not want him for his moral worth or his beautiful eyes. We can assure him, also, that the citizens…who thought well of him when he was on Mayor Kennelly’s ticket will not think equally well of him now that he has deserted to the enemy.

….It is not an amiable weakness to desert one’s principles for the sake of a little flattery and in the hope of a little more notoriety. People who do that can expect to be laughed at and will be fortunate if they are not despised.

Despised!

This episode got Morris B. Sachs a single quick appearance in Mike Royko’s “Boss”:

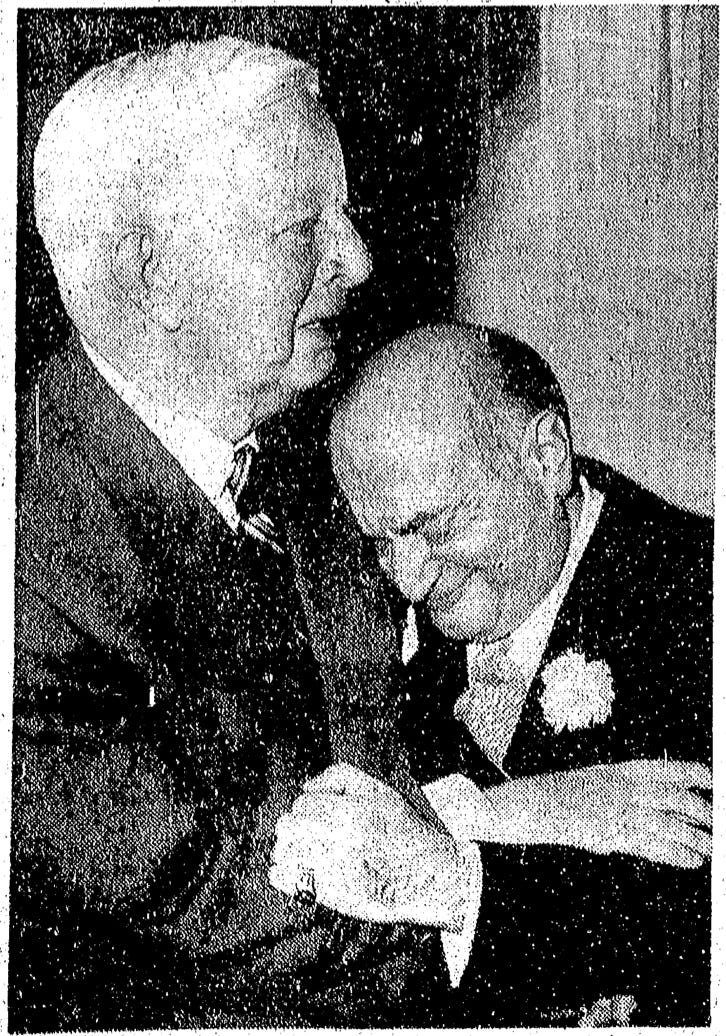

“The night they [Kennelly and Sachs] lost, Sachs became part of one of the most famous news pictures in the city’s history, wrapping his arms around the taller Kennelly’s neck and resting his sobbing, contorted face on his chest.”

“Daley called Sachs and asked him to join his team as the city clerk candidate. Sachs wrapped his arms around Daley’s neck and beamed.”

The Morris B. Sachs flip from reformer Mayor Kennelly to obvious Machine striver Richard J. Daley was a bona fide city morality play. Republican mayoral candidate Robert E. Merriam, a real tower of Chicago reform politics who left his seat as 5th ward alderman to run for mayor that year, blasted the process:

“Regardless of the public, they shuffle candidates, they drop candidates, they dump candidates like Mayor Kennelly, and then pick their own kind,” said Merriam at a political dinner. “As machine leader, [Richard J. Daley] picks the nominating [slate] committee which turns around and picks him to run for mayor. It is simply a case of Daley picking Daley. It is a cozy arrangement which insures selection of the machine choice rather than the people’s choice.”

Some Trib readers supported Sachs.

Andrew A. Steinberg pointed out that Sachs had gotten 64,000 more votes than Kennelly in the primary—why shouldn’t he get picked up by the Daley ticket? “This outpouring of votes for a man who had never been associated in politics was a tribute to his reputation,” wrote Steinberg. “Mr. Sachs has given too much of himself toward philanthropies, science, and young talent to be criticized in an aimless manner.”

“Why not give him a try,” wrote “A Faithful Reader.” “He may do good where others failed. If you get one good man in, you may be making room for more good men to get in, too. Don’t condemn him without a try.”

Others went as snide as the Tribune itself.

“Let us give Mr. Morris B. Sachs another opportunity to cry after the April 5 election,” wrote “A Former Democrat.” “He has convinced his loyal supporters that he is only a cheap politician.”

Hiram Wilson Sheridan of Glen Ellyn went even darker:

“Could I suggest that your attitude of ‘haha’ toward the lachrymose Morris B. Sachs is not well taken? The defect of human character is much too widespread to be funny. It is frightening.

“Mr. Sachs has illuminated for a flickering second the truth of the Ancient Greek—was it Aristotle?—who said, ‘Anyone who desires public office is not qualified for it.’”

Richard J. Daley won the election of course, and with him, Morris B. Sachs. Another Tribune editorial opined that Sachs “proved himself to be the champion anti-machine candidate and the champion machine candidate.” The Trib figured voters were either “sadly deficient in common sense” or so cynical, they “were not the slightest bit surprised when Mr. Sachs suddenly dried his tears and moved into the enemy camp.”

But the Trib and other naysayers had yet another surprise coming. Morris B. Sachs didn't just believe in third acts. He went for a fourth, and tried for a fifth.

Sachs won 737,169 votes on Daley’s ticket—29,000 more votes than Daley himself. He donated his $1,000 monthly treasurer’s salary to charity, arranging for a small board of advisors to pick the recipients. The Daily News reported that since taxes brought Sachs’ net pay down to $830, he tossed in $170 himself every month.

Now here’s the fantastic part you really didn’t see coming:

Sachs instantly started trouble by firing the Machine flunkies who were goofing off in the treasurer’s office. He fired three “politically influential” employees in five days, and told the rest of his employees—according to Sachs himself:

“I told them, ‘I love you all. I expect an honest day’s work from each of you. If you don’t want to give me an honest day’s work, then you’d better see your angels and get other jobs.”

Sachs fired a guy whose sponsor was 26th ward committeeman and Alderman Matt Bieszczat, who in 1972 is still one of Mayor Daley’s closest political cronies. See Mike Royko on December 7 for the hilarious story of Paul Simon seeking the Machine nomination for governor, and having to go through Bieszczat to get it.

In 1955, Bieszczat told reporters that Sachs “should drop dead.”

“Mr. Bieszczat is an honorable man,” Sachs responded. “I hope to meet him. With the type of language he uses he should be governor of the state. Maybe he can even be President. His remark was really brilliant.”

Mayor Daley told the press that Sachs’ firings weren’t “encouraging” for the morale of precinct captains. Sachs received hundreds of fan letters, but not, we can assume, from Mayor Daley.

Still, Mayor Daley couldn’t say anything bad publicly about Sachs. The new treasurer announced he would reduce his own budget by $27,355 for the following year, then announced another $10,000 reduction because he only needed one employee to process welfare checks, not the three people who were currently doing the job. That meant two more Machine flunkies out on the street.

Sachs went on to unsuccessfully run for the Democratic nomination for governor in 1956. Mayor Daley did not support him. We’ll never know if Sachs would have tried again for higher office. Sachs died suddenly overnight of a massive heart attack in 1957 at age 61, leaving his entire estate to his wife.

Much as we here love Mike Royko, we have to acknowledge that Morris B. Sachs got short shrift in “Boss.” Mike was writing “Boss” nearly 20 years after Sachs’ short stint as treasurer, knowing how it turned out. Maybe Morris B. Sachs would have gone the way of most politicians if he’d lived, but while Sachs was in office, it appears he was a pretty kick-ass treasurer—certainly by Chicago standards.

I guess it was too tempting not to contrast those two pictures of Sachs with Kennelly and Daley. But since we know that city treasurer Sachs immediately started firing the Machine city employee laggards that Mike loved to skewer, we can imagine what was really going on behind that beaming smile as Sachs shook newly-elected Mayor Daley’s hand and faced the flash of photographer’s cameras in 1955.

I wish Mike had included a few lines on Morris B. Sachs’ brief time as a thorn in the newly-minted Mayor Daley’s side. But no doubt Mike was overwhelmed writing his first book while continuing to keep the quality of his column at such a high level that he won a Pulitzer Prize for that time period, not to mention raising his still-young family. Who knows how many interesting threads simply couldn’t be entirely woven into “Boss.”

Morris B. Sachs died at home at 4950 S. Chicago Beach Drive, which is the Powhatan Apartments. I love thinking about a penniless orphan coming across the ocean by himself in 1910, working his butt off, and growing up to live in the Powhatan.

The Powhatan is easily Hyde Park-Kenwood’s classiest building. It’s the kind of place where you wouldn’t mind living in the elevator.

Here’s the swimming pool, which looks like it could be at The Overlook Hotel in “The Shining.”

This must be the ballroom. Fun fact, someone I know who lives at the Powhatan taught herself to rollerblade in the ballroom during the first winter of Covid.

Lastly, here is the living room of a current unit for sale.

Technically the Powhatan is in Kenwood, because it’s just north of 51st St. But really it’s East Hyde Park—specifically, “Indian Village,” due to the large number of high-rises with Native American names in this little wedge-shaped area nestled between the Illinois Central railroad embankment on the west and Lake Shore Drive to the east, between 51st and 47th Streets.

The Powhatan is a city landmark. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks lists its construction as 1927-29, by architects Robert DeGolyer and Charles Morgan. An old Landmarks Commission page in the Wayback Machine states:

The facade of this 22-story, luxury-apartment highrise reflects Eliel Saarinen's influential, streamlined design for the Tribune Tower competition of 1922. Terra-cotta ornamental panels feature scenes from American Indian culture, befitting a building that was named for a famous Algonquin Indian chief.

Mayor Daley and a host of other officials attended Morris B. Sachs’ funeral a few blocks away from the Powhatan at Hyde Park’s Congregation Rodfei Zedek, 5200 S. Hyde Park Boulevard—which is still there, in a new building.

Over 2,000 people visited Morris B. Sachs’ wake.

“We are hardly able to assess the magnitude of our loss and the full significance of his life,” Rabbi Ralph Simon told the crowd. “Of one thing we are indeed certain, Morris B. Sachs has already become a symbol of the fulfillment of the 20th century American dream.”

“A man doesn’t attain the business and political success that came to Morris B. Sachs without having a wide band of practical sense,” wrote the Daily News in an editorial after his death. “Undoubtedly, he was well aware of the commercial value of his kindly, benevolent and sentimental approach to matters in general.

“At the outbreak of World War II, he wrote a letter to customers of his clothing stores who went into the armed services, and sent them $88,000 worth of bills ‘Paid.’”

Note: That’s $1.5 million in 2022 money.

“This act of generosity probably was a wise investment in good will and, subsequently, in business.

“There was nothing hypocritical, however, about Mr. Sachs. He was being himself, and his sincerity added strength to his kindness. If material rewards came to him because of his open heart and hand, it should be a cause for rejoicing that fortune can be so discriminating.”

How many politicians get newspapers editorials like that?

In the mid 1960s, the Morris B. Sachs stores expanded into Park Forest Shopping Plaza and opened a large store at the southeast corner of Western and 95th, near Evergreen Plaza. The Milwaukee/Division store had already closed. The original Englewood store on Halsted, and the Loop store, lasted until the firm filed for bankruptcy in 1969. The company was initially granted permission to continue operations by bankruptcy court, but the stores closed soon afterward.

Morris B. Sachs stores tried to follow customers to the new-fangled malls, just as the orphaned immigrant Morris B. Sachs followed his customers to their homes when he peddled clothes on the South Side a half century earlier. This time, it just didn’t work out.

Morris B. Sachs is buried at Rosehill Cemetery, along with such other Chicago luminaries as Richard Sears and Montgomery Ward.

Let’s imagine he’s singing, dancing and acting up in heaven.

As we here all know, weekends could be sad for a Daily News family because Mike Royko wasn’t in the Daily News’ single weekend edition. So we look for Mike elsewhere on weekends.

This week, Mike turned up in the rest of the paper twice. Let’s take a peek.

May 10, 1972

Mike garnered a compliment from Daily News TV columnist Norman Mark in his coverage of the annual local Emmy awards—which itself may be of interest.

Norman Mark notes that Chicago’s PBS station, Channel 11, “promises to devote a Saturday night to broadcasting excerpts of the 16 shows and performers who won local Emmys”. If they do, it’ll be the first time Chicagoans see most of the winners, because these shows are typically “broadcast at odd times or before small audiences.”

“After all, excellence is no guarantee of popularity,” writes Mark.

The local Emmy’s used to be televised, but Channel 7 and 9 are boycotting them in “childish snits…about something or other and this has caused the academy to become too impoverished to present the awards on local TV.”

Instead, the awards were held unbroadcast in the Grand Ballroom of the new Playboy Towers Hotel, because in 1972 it’s perfectly normal and acceptable to hold anything from charity fundraisers to the local Emmy’s in a hotel and nightclub owned by a porn magazine if it also runs enough articles.

“B.J. and the Dirty Dragon” walking off with two Emmy’s.

Other Emmy winners included Walter Jacobson, then with Channel 5, for “Chicago: How It Works,” an interview with Mayor Daley including, presumably, plenty of fun Walter commentary. Would I love to see that. Did Mike watch, and throw underwear at the TV? Norman Mark reminds us that Jacobson used to work for Channel 2, but left for Channel 5 in 1971, “after unsuccessfully attempting to do a show about Mayor Daley”.

It’s a shame that Walter’s Emmy-winning piece on Mayor Daley isn’t on YouTube or elsewhere, as far as I can see. But, for fun, here’s a montage of promos from when Walter first teamed up with Bill Kurtis on Channel 2.

Norman Mark lists the other winners, then gets back to commentary:

“That list actually has very little to do with the local scene,” Mark writes. “In the last year we have had more pollution scares, yet no Chicago TV station did a program on that subject worthy of a local Emmy. The same goes for our continuing political scandals, the widening gulfs between the races, classes and age groups in our community, and a dozen other subjects.

“In a single month, Mike Royko alone probably does more investigative reporting than all Chicago radio and television stations combined.

“The local Emmy’s were supposed to honor excellence. Instead they highlighted how few good local TV shows we see.”

May 11, 1972

And along with the likes of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor and John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Mike turned up in Bob Herguth’s page 5 gossip column, though admittedly a little further down.

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Mike already trimmed the verbal fat, so he doesn’t need to be summarized Reader’s Digest-style, either. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, but especially to give the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. You can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there are some columns covered here you will never read elsewhere. If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career and including a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

Do you dig spending some time in 1972? If you came to MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY from social media, you may not know it’s part of the book being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

To get MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY in your mailbox weekly along with THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 and new chapters of the book—

SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE!

Another Lady of Spain link for you: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A65QFlXHyBw