Mike Royko 50 YEARS AGO TODAY: The Lincoln Park pirate visits Mike's office

Weekly compilation January 17-23, 1972

To access other parts of this site, click here for the Home Page.

Why do we run this separate item, Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today? Because Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the serialized novel central to this Substack, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” lived in a Daily News household. The Bertolucci’s subscribed to the Daily News, and back then everybody read the paper, even kids. And if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko. Read the daily Royko briefing Monday-Friday on Twitter, @RoselandChi1972.

January 17, 1972

A flowery bit of generosity

Mike sticks up for a secretary done wrong. This is one of those columns where Mike, like a magician, begins with misdirection so we don’t see the trick until the end.

“Big men in finance and commerce are often thought of as cold and hard-headed, their eyes fixed upon the ledger’s profit column,” Mike begins. “There are such men, with their tape-ticker hearts, but there are also men like Tom Mills. Mills is president of Tom Mills Brokerage Co., 333 N. Michigan”.

Mike figures Tom Mills would be too modest to tell everyone about how he treated his new executive secretary, Mrs. Karen Britt—so Mike steps up.

Mrs. Britt worked for Tom Mills for a month, without incident, when her mother was suddenly diagnosed with cancer and days to live on New Year’s Eve. Her husband called her office on Monday to say Mrs. Britt needed to be with her mother and would not be in that day.

Mrs. Britt’s mother died that very day. Mrs. Britt called the office to say she would return after the funeral, set for Thursday.

“On Wednesday—the day before the funeral—a letter arrived at Mrs. Britt’s home,” writes Mike. “She opened the envelope as she was being driven to her mother’s wake. It contained a check for two weeks’ pay. There was also a letter from Mr. Mills.”

Mr. Mills explained in the most cold, technical language possible that “we” have sympathy for anyone whose close relative passes away, but a seven-day absence isn’t “a good beginning”. So the paycheck was severance. “You have a responsibility toward a mother. But you also have a responsibility toward an executive position when you take one on,” Mills finished.

Take a moment to enjoy imagining Mr. Mills’ surprise when Mike Royko called to chat.

Mr. Mills told Mike that Mrs. Britt should have come back to work for the two days between her mother’s death and her funeral. He had to hire a temp, which is “a lot of bother and a lot of work.”

So why did Mike say Mr. Mills was not a hard-hearted businessman?

“Because he proved that down deep he has a heart of gold. At the very same time that he fired Mrs. Britt he sent a plant to the funeral home. What a softy.”

This week, Monday was an unofficial 1972 Secretary’s Day. See this week’s THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 for another secretary’s 1972 tale in the January 17 entry.

January 18, 1972

Lullaby of Clark St.

Another of Mike’s regular columns of “Letters, calls, complaints and great thoughts from readers”. So many good letters to choose from today, but we’ll have to go with one:

“J.G. Chicago: I was walking east on Superior St. this morning, toward the lake, when I saw an illegally parked Rolls-Royce. On the dash there was a kind of official police business sign. The license of this protector of the law was Illinois 67. Have you any idea which of our lawmen has a big Rolls Royce?”

“COMMENT: The car belongs to Anthony G. Angelos, a wealthy banker and real estate man, who dabbles in politics. He is the man who flew to Greece to try to rescue a former Playboy magazine Playmate who was locked up for possessing marijuana. Angelos is one of many prominent businessmen who are deputy sheriffs, authorized to carry guns and badges and make arrests. They get this authority by being listed on the sheriff’s roster as weekend police court bailiffs. They say they take these weekend jobs because they are public-spirited citizens. And because the badge, gun, and parking permit make them feel big.”

But Anthony G. Angelos was so much more than just a rich guy using a fake deputy badge to park his Rolls wherever he wanted. His true notoriety came in 1973.

As it turns out, Anthony Angelos is so ridiculous, it would take a New Yorker or Chicago Reader profile to do him justice. But we’ll streamline a bit.

Looking back from the date of this column: Angelos was a wealthy connected banker, but he was also a slumlord. In 1955, the city building department ordered his Eagle hotel at 516 S. State to post signs “warning the building is dangerous and persons who entered did so at their own risk.”

A real renaissance man, Angelos owned or co-owned quite a few different bars and liquor stores over the decades. In 1954, he owned “several rooming houses” like the dangerous Eagle, as well as a bar at 512 W. Madison where two teenage maids who worked in Winnetka got drunk and then accepted an invitation to Angelos’ apartment at 27 E. Bellevue—where they tried to jump out his third-story window to the adjoining building to escape from him.

Barbara Kieta, 18, made the leap successfully. Lorrie Braaten, 16, did not.

Braaten was hospitalized with injuries from the three-story fall. According to the Tribune, Miss Kieta said “they feared Angelos and the apartment door was locked. He said they asked to come to his apartment to use the bathroom.”

Going forward, in 1973, newly-elected Illinois Gov. Dan Walker appointed Angelos to head the scandal-plagued state insurance agency. The Tribune soon printed a lengthy article of literally nothing but direct quotes from Angelos denying all the allegations that surfaced against him. He felt they were all unfair.

A Tribune editorial headline called the Angelos affair “Mr. Walker’s Watergate.” It's not surprising Walker went to jail for bank fraud a few years later for something else, since the main issue here was that it was illegal for anyone in the liquor industry to give political donations, and multiple bar-owner Angelos had given Walker hundreds of thousands of dollars. Eventually Walker claimed those donations were loans, but Angelos had to decline the appointment to run the state insurance agency.

In 1984, Angelos was convicted of defrauding the failed Des Plaines Bank, which he owned. The federal judge sentenced him to five years in prison and called him “the most corrupt banker in Illinois in the last decade”.

One of the charges involved mail fraud for secretly buying the Dallas Playboy Club.

January 19, 1972

Cascio works on his image

What Chicagoan can’t hum Steve Goodman’s 1972 classic “The Lincoln Park Pirates”?

Thank Mike, whose columns about the infamous Lincoln Towing Services made owner Ross Cascio almost a household name—and this is one of Mike’s best Cascio entries

“Several years ago I discovered Ross Cascio, the tow truck terror, and predicted he would become a big success,” starts Mike.

He describes how Lincoln Towing employees towed cars and charged owners twice the going rate to retrieve them. “To intimidate those who objected, Cascio hung bats, blackjacks, chains and other pacifiers on his office wall. And a huge, red-eyed, black-tongued dog encouraged people to pay.”

“If a person tried to escape with his car, or acted tough, Cascio’s men would dance on his chest….And every time I wrote about Cascio, he would say, ‘That just brings me more business.’ Which was true….I knew that someone with Cascio’s qualities—greed, pitilessness, and a 19-inch neck--had to become a success in Chicago.”

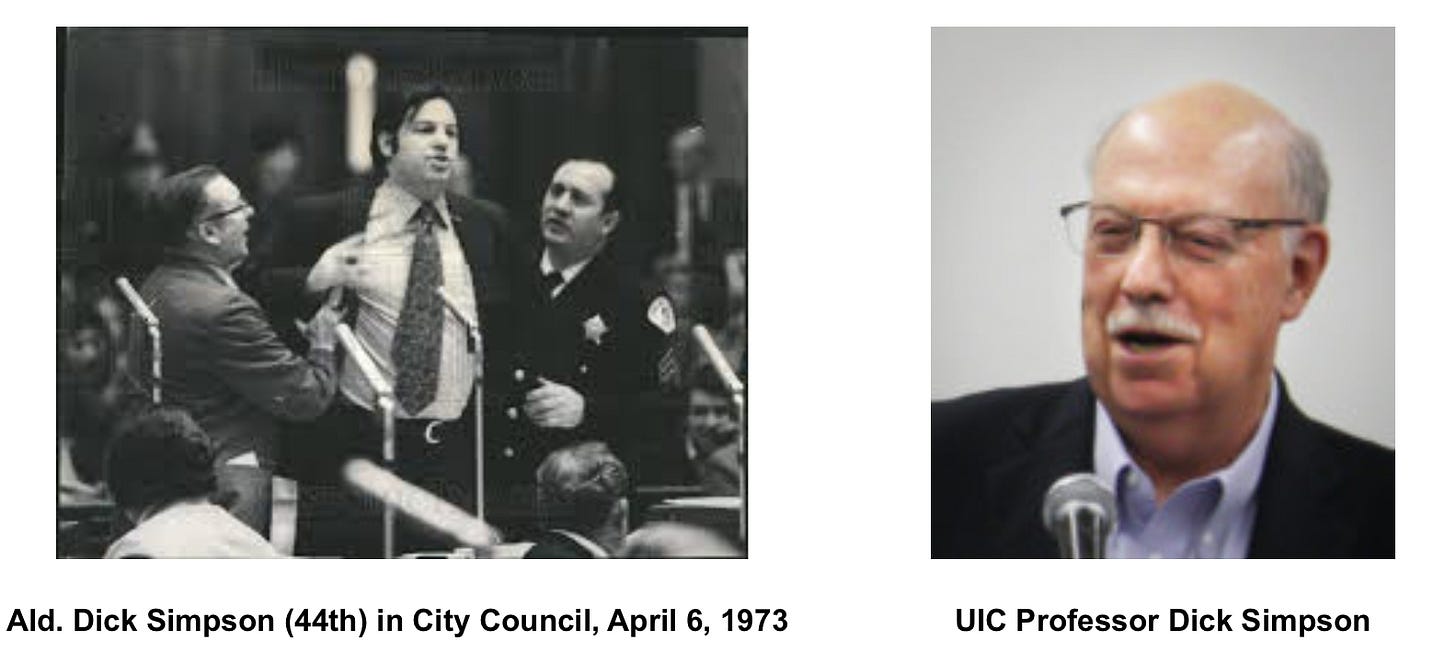

Mike started writing about Ross Cascio’s towing company in 1967 and kept it up, so by early 1971 Lincoln Towing Services was an issue in aldermanic campaigns. Aldermanic candidate and Circle Campus political science professor Dick Simpson filed a $1 million lawsuit against Lincoln Towing, telling the Tribune that other area firms charged $12 -$15 per tow compared to Lincoln’s $28.

Simpson went on to win office and become one of the biggest thorns ever in Mayor Daley’s mayoral side—

—but his lawsuit was dismissed. After his election, Ald. Simpson (44th) and Ald. Bill Singer (43rd) introduced an ordinance to license and regulate the towing companies, but it got buried in the Licensing Committee.

“It was one of the things that helped get me elected,” Prof. Simpson said when I called him. “They created fliers in favor of my opponent because I had attacked them in a press release saying if I was elected I’d work to try and solve the Lincoln Park Towing problem.”

Ironically, the Lincoln Parkin towing people put the fliers under car windshields in the 44th ward. And they went further, says Simpson: “I had a series of run-ins with them and I had death threats which I think came from some of their drivers.”

In 1972, as Mike wrote today’s column, Lincoln Towing had already lost a civil case brought by chemist Hysam Chekali. According to a Tribune account, Chekali “said his car was towed from a legal parking space and that when he went to retrieve it from the towing service, he was attacked and knifed by one of the employees.” Chekali won $34,000 in damages.

Ross Cascio would sue Mike for libel twice, and lose.

Mike writes about Cascio today because he visited Mike at his office with his new PR man.

“’I am Pete Harlib,’ the PR man said, sticking out five fingers, the smallest of which was circled by a diamond ring. ‘I’m here to tell you that we have an operation at Lincoln Towing Service that is as clean and respectable as anybody’s….We are as clean and legitimate as Marshall Field and Co.’”

“I didn’t argue with Mr. Harlib,” writes Mike, “but I have never heard of a customer at Field’s being sliced from navel to nose, as happened to a motorist who tussled with one of Cascio’s men.”

Mike has an entertaining visit with Cascio and his PR man. As they left, Harlib claimed to know a Daily News executive, and encouraged Mike to ask around about him.

“So I did,” writes Mike. “I asked a veteran police reporter about Harlib’s police career. All he could remember was that when the infamous Summerdale Police Scandal erupted in 1960, the desk sergeant in the Summerdale Police Station was Pete Harlib.

“He ought to do wonders with Cascio’s image.”

Not familiar with the Summerdale police scandal? We’ll have a post on that eventually, but in the meantime, check out the Chicago History Podcast episode here.

January 20, 1972

Wide world of poison peril

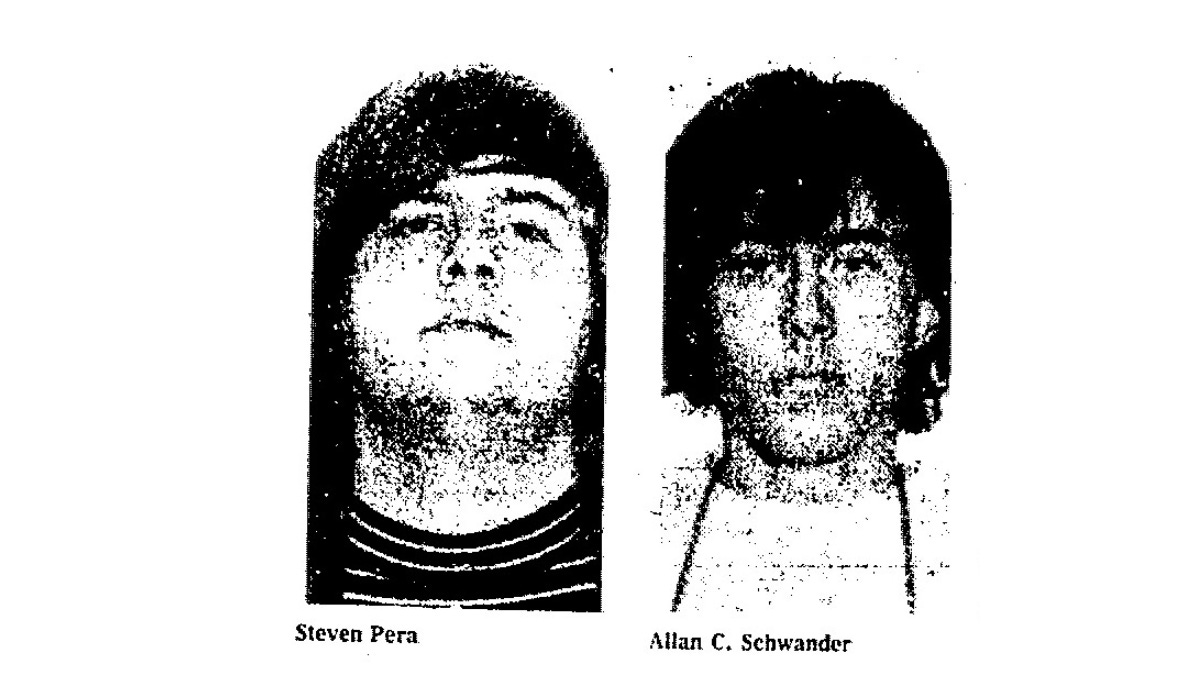

Remember how the FBI and local police arrested two long-haired City Colleges students this week, and State’s Attorney Ed Hanrahan charged them with conspiracy to commit mass murder by poisoning Chicago’s drinking water?

The two long-haired young men had grown some bacteria cultures at a lab at the Mayfair campus, now Truman College. A friend of theirs, invited to join their secret group meant to survive the water poisoning and create a new master race, told the FBI. See this week’s THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 for more.

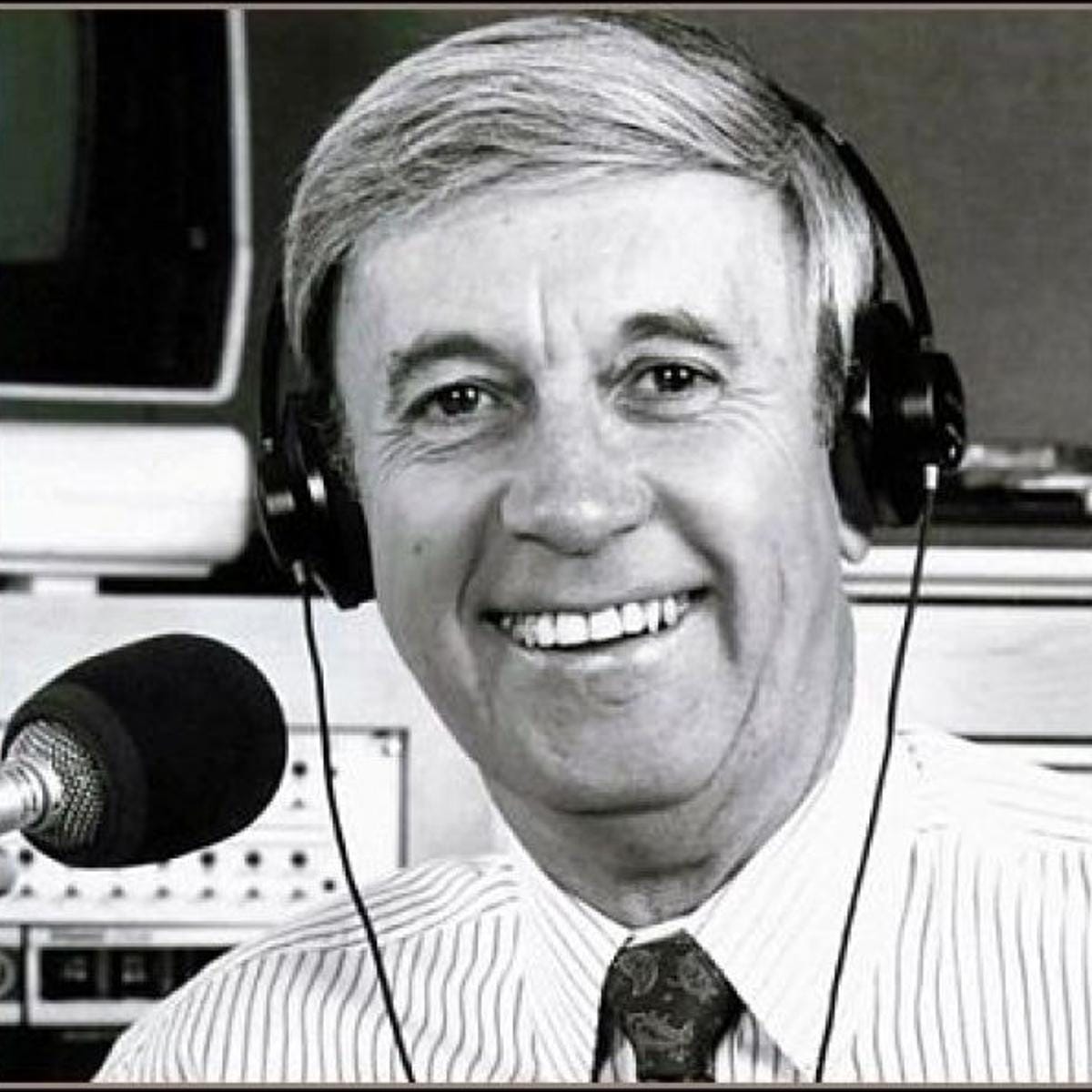

Wally Phillips broke the news to Chicago on his top-rated WGN radio show, and many Chicagoans were afraid to drink the water for a while, though annoyed Chicago Water Commissioner James Jardine called it “a hare-brained scheme” that could not possibly work, if only due to chlorination.

Mike may not be taking this threat to public safety very seriously.

“The great water menace touched off concern and fear among many Chicagoans,” Mike notes. “Moments after the first alarm was spread by a morning disk jockey, switchboards everywhere lit up.”

There are so many questions! Mike offers to help with a Q & A on the crisis.

“Q-On the first morning of the Great Thirst, I was afraid to drink the water. However, I had to use water to brush my teeth…I was careful not to swallow any of the water. But should this threat again occur, am I endangering myself?”

“A—Only slightly. Had the danger been genuine, only your teeth would have had typhoid fever…use a substitute. I suggest wine. With a strong-flavored, striped toothpaste, try a full-bodied red wine such as a Burgundy, or a Rhone.”

“Q-A friend and I have taken a physics course at school, and we have decided to create a nuclear device powerful enough to make the world rotate the wrong way. What is our next step?”

“A- Have a third friend tip off Ed Hanrahan about your plot and call your favorite morning disk jockey. It should be fun to see everyone in the city digging a shelter.”

January 21, 1972

Things tough, but he can’t kick

Recently, Mike was in line at a vending machine that was cheating people by taking their money and not producing coffee. Mike advised the cheated person in front of him how to kick the machine, if only to get revenge. Then he wrote a column explaining the best way to kick vending machines, so as not to hurt yourself.

Now, 21-year-old Jim Johnson has come to Mike because he’s in trouble after kicking two cheating vending machines at the Illinois Central RR employee cafeteria, on behalf of two female colleagues who’d lost money.

“Both machines promptly gave forth candy and sweet rolls” after the kicks, Mike notes. But Johnson “didn’t know the entire scene had been observed by an informant, a spy, a company fink, or maybe somebody who was jealous of Johnson’s success with the ladies.”

Johnson’s boss calls him into his office. He’s irate. “They said that they thought I might have broken the machines by kicking them, because on Monday they didn’t work. I told them that of course they didn’t work on Monday, because they weren’t working very good on Saturday. I wouldn’t have kicked them if they had been working right. A person doesn’t kick a machine when it works. What is the sense of that?”

Johnson can’t kick the machines anymore, or he might get fired. Mike compares him to John Henry, who drove more steel than a new machine, though it killed him.

“Give the candy machine one more kick, Jim Johnson,” Mike concludes. “Don’t you want people to sing about you some day?”

FYR: The word “fink” was very popular at this time. Mike used it just now when he wrote that Johnson didn’t know he’d been observed by “an informant, a spy, a company fink”.

In the popular Wizard of Id cartoon, a character would walk around with a sign that read “The King is a Fink.” I think I have a Wizard of Id book around here somewhere—yes. Here it is.

January 21-22, 1972

As we here all know, weekends could be sad for a Daily News family because Mike Royko wasn’t in the Daily News’ single weekend edition. So we look for Mike elsewhere on weekends.

Let’s take a stroll in the “People I Have Known, Or Heard Of, Or Imagined” section of Mike’s first book of columns, 1967’s “Up Against It.” This is one of Mike’s books that doesn’t include the column date, but by definition, it’s somewhere between 1963 and 1967.

Dutch Louie

“Dutch Louie never gave much thought to whether he and his position in life had much dignity,” Mike begins, giving us a clue about what brings Dutch Louie to his mind after all these years. It’s the new Great Society poverty programs.

“If he were alive today, he’d probably think about it because dignity has become part of the social welfare package. It is not enough today to have a job. The job is expected to have dignity.”

“Someone who didn’t know Dutch might have thought he was a bum,” writes Mike, but those who knew Dutch did not consider him a bum because he had a job. Dutch worked in a neighborhood tavern near Logan Square, doing everything from sweeping and mopping to “acting as backup man to the watchdog in the event of a burglary.”

Is Dutch an alias for someone who worked for Mike’s family’s tavern, the Blue Sky Lounge at 2122 N. Milwaukee? The family lived upstairs from the bar. I don’t recall this being covered in Richard Ciccone’s great biography (“Mike Royko: A Life In Print”), and I don’t see it in flipping through for this post. “I think it may be one of Mike’s Slats-like characters,” says Rick Kogan. If anybody has information on this, please let the rest of us in on it via the Comments section, or email me at RoselandChicago1972@gmail.com.

“His pay was a clean cot in the basement, a reasonable supply of whisky, three meals a day, a few dollars for special occasions and new clothes when he wanted them, which was every Easter.”

Dutch saved some tavern patrons by volunteering to test a double shot of whisky from salesman during World War II, when the quality of supplies was questionable. “The color of his skin and the flow of tears from his eyes was a good gauge of the liquor’s quality.”

Among other community services, Dutch would get a horse and wagon to go junking up and down the alleys during the summer, taking neighborhood kids with him to see the city. Was Mike one of those kids? It’s great to imagine.

“Considering everything, it wasn’t a bad life,” writes Mike, “at least for someone who wasn’t cursed with too much ambition.”

One day, Dutch didn’t come upstairs from his basement cot, and the tavern owner found he’d died in his sleep. “There is nothing more dignified than going quietly, everyone agreed.”

But then they found and informed Dutch’s sisters, who lived in a toney North Shore suburb.

The sisters whisked Dutch away from the neighborhood funeral home where he was about to have a dignified wake and “They snuck him into a funeral home where nobody knew him or them…the two sisters got it over quick and went home. It wasn’t a very dignified thing to do.”

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Mike already trimmed the verbal fat, so he doesn’t need to be summarized Reader’s Digest-style, either. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, but especially to give the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. You can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there are some columns covered here you will never read elsewhere. If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career and including a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

Do you dig spending some time in 1972? If you came to MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY from social media, you may not know it’s part of the book being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

To get MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY in your mailbox weekly along with THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 and new chapters of the book, SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE!