To access all site contents, click HERE.

On October 18, 2022, the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame presented Rick Kogan with its Fuller Prize for lifetime achievement. It was as an evening both touching and hilarious, but mostly full of love flowing between Rick on stage, and every one in the Chopin Theater seats. You’ve never heard so many people murmuring “so well deserved” to each other at the same time.

This is a look at early Rick, a piece I was honored to contribute to the evening’s program. I hope to get a link to a recording of the event too, since any Rick fan would enjoy it immensely. Get a PDF of the whole program here, with terrific articles by so many people, from Patrick Reardon to David Mamet.

P.S. Bonus newspaper stuff at the end.

Rick Kogan’s voice warms you up like the liquor he assuredly likes to drink--he once told the Reader’s Michael Miner that Roger Ebert “God love him” failed to make him stop.

And it’s smokey, like his cigarettes.

Of course, Rick’s voice is gravelly too, the word most often applied to it. With that voice, Rick can and does call literally anybody “honey” and “sweetheart”--for a wildly divergent spectrum of reasons. Coming from Rick, the meanings of those words aren’t in any dictionary. It’s all in his voice, like a tonal language.

Rick was born for radio as surely as he was born into newspapers. Chicago radio. Chicago newspapers. Chicago, period. Hell, it’s like he was pickled at birth in a jar of Chicago history brine, and somebody unscrewed the lid and plucked him out just in time to work for the Daily News before it folded, all crunchy and fresh and ready to go.

Exhibit A: His baby shower got a plug in the Tribune in 1951.

Named for the old press haunt Riccardo’s—his full name is “Rick,” not “Richard”--Rick grew up in a classic six-flat smack in the heart of the Old Town Triangle, long before that neighborhood’s name meant “you can’t afford it.”

Just heading down the hall at 1715 N. Park Ave., young Rick might at any time run into family friends like Studs Terkel, Nelson Algren, Willard Motley, Mike Royko, Marcel Marceau. Or James Jones (“From Here To Eternity”) camping on the couch for weeks at a time.

Rick’s parents were every bit up to entertaining that caliber of guests.

Herman Kogan was a legendary Chicago newspaperman who created the Daily News’ arts section, Panorama, in 1963, and later edited the Sun-Times’ “Showcase” and “Bookweek” sections. Herman also hosted “Writing and Writers” on WFMT for 14 years, and authored books still on any required Chicago reading list, like “Lords of the Levee” with his friend Lloyd Wendt.

The sound of Herman’s typewriter must have been a staccato lullabye to baby Rick, and it was definitely the steady soundtrack of his childhood and teen years, whether at home or hanging with dad at the office.

Marilew—M’Loo to friends and loved ones—was the kind of character who had Tribune owner-publisher Col. Robert McCormick eating out of her hand. And as most readers here probably know, Col. McCormick was more the biting type.

“There are not many people around who worked for the Colonel, fewer still who knew him and perhaps just a couple left who actually rode in his limousine,” Rick recounted for the Tribune. “But my mother did all three.”

Eighteen-year-old Marilew Cavanagh worked days at the Trib, and nights she went to college classes. In the Trib’s fashion and travel departments, she did everything from writing movie review synopses to memos for section editors.

Then one day her boss gave her an envelope with strict instructions to deliver it to the Colonel personally--not one of the two secretaries whose desks flanked the Colonel’s office door in Tribune Tower. As Marilew argued the point with one of the secretaries, Col. McCormick’s door opened. The Colonel’s German shepherd emerged and ambled over to Marilew.

“She bent low to pet it,” Rick wrote, “and then said to the dog: ‘Look, you’re closer to the Colonel than anybody. You take this to him.’”

As Marilew held the letter out to the dog, Col. McCormick guffawed from just inside the doorway. Then he came out to meet the cheeky young lady. After that, the Colonel’s chauffeur often picked Marilew up after night classes for the ride home to Rogers Park.

Besides raising Rick and his brother Mark, Marilew headed the public relations department at the Art Institute, then managed Midwest publicity for Doubleday Books through most of the 1960s. She introduced her old friend Studs Terkel to her new friend, Sun-Times cub reporter Roger Ebert, just one of the matches Marilew engineered. Rick has noted that Nelson Algren probably slept with his aunt because he couldn’t sleep with Marilew.

So Rick moved through a personal Chicago history at home, kind of a live-action Studs Terkel oral history.

And his family newspaper background ensured that he saw some very public history too--like the part of the 1968 Democratic National Convention that played out at Michigan and Balbo instead of the Ampitheatre.

As a teenager, Rick watched what would be called a police riot from the glass front doors of the Conrad Hilton. He was helping out as a summer job in the press room in the hotel basement. As he put it when I interviewed him for a project a few years back:

“I was fuckin’ 16, getting coffee for these jokers. Yeah, that was an experience. I was wearing my father’s Marine Corps jacket, that was my outfit. My hair was about as long as it is now, and I remember standing behind the cordon of police that were blocking the entrance to the Hilton. And out there, there were people who looked like me, just a few years older, getting the shit beaten out of them. I was interested in girls and playing football. I mean I was not politically motivated at the time. Had no idea what was going on out there. I would say I was politicized at that time.”

That wasn’t hyperbole. Rick really was interested in girls and football in 1968. Here he is, fifth player in back of coach Art Davis, in a 1967 Daily News article by Harvey Duck on the Latin School’s hard-working but challenged football team that year. Harvey Duck proclaimed Rick “an effective back throughout the season.”

Rick learned a lot that day in 1968, and not just by noticing what was right in front of his face. He took in the police riot, and then he took in the city’s reaction.

“I was amazed at the adoration that Daley got,” Rick said, still a bit stunned. “That taught me a lot about Chicago too. They were glad, for the most part, the majority of Chicagoans were glad that [Daley] did what he did. There’s no doubt in my mind about that. They certainly sided with the police officers because again you fear things that you don’t know—these guys with long hair and strange clothes were not part of your scene. Especially in the neighborhoods where people lived. So that’s what amazed me. The real reaction had nothing to do with what was happening there. Even with Cronkite and the images on TV and the whole world is watching—OK, the whole world was watching, and [Chicagoans] said ‘Good, beat the shit out of those guys.’ Daley was a hero.”

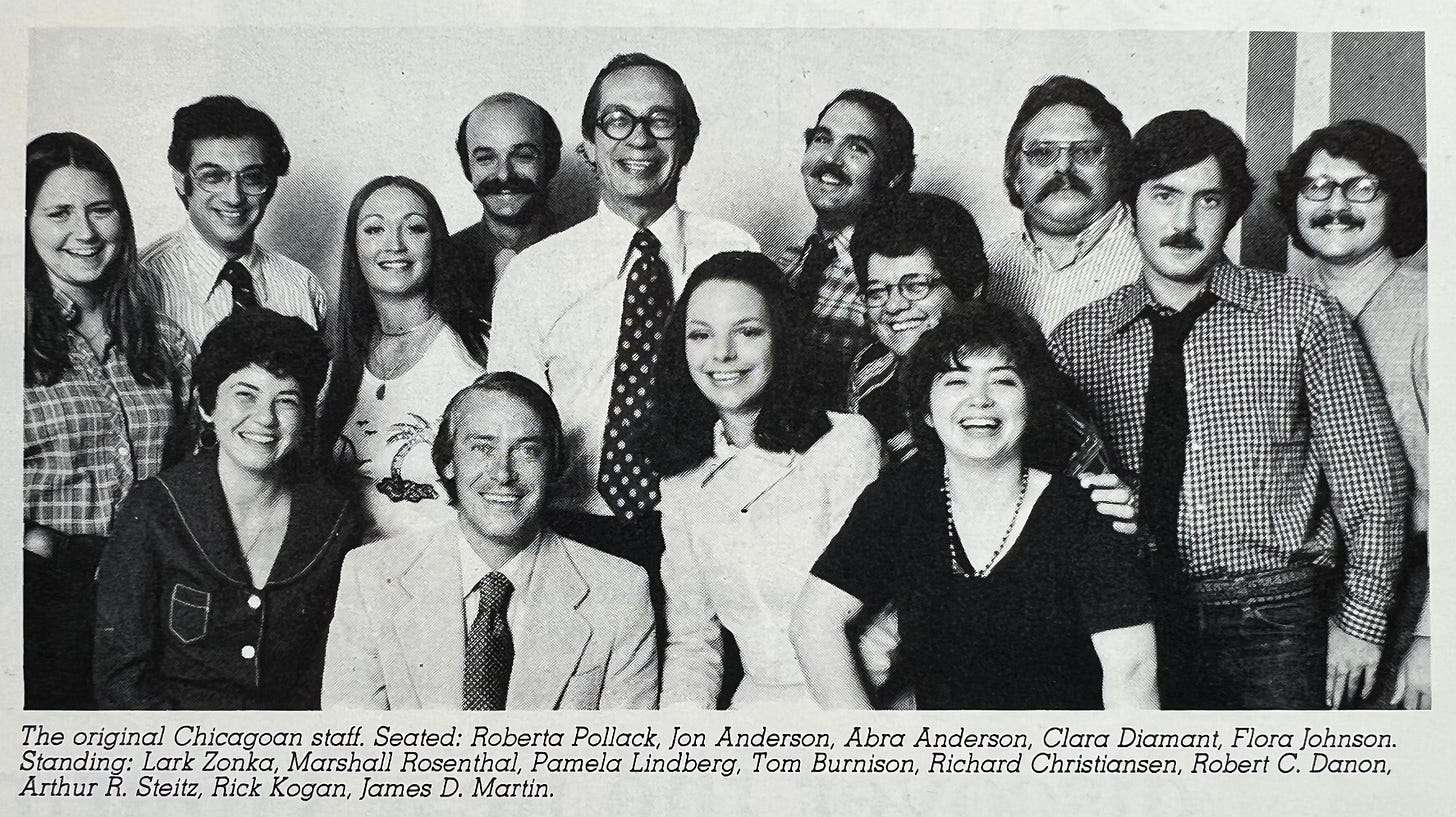

After high school, Rick spent about three months at Circle Campus, figured out it wasn’t for him, and started a Bohemian spree that included driving a cab, traveling in Spain, living in New York’s Bowery. A travel story from abroad soon helped him land a staff position at Jon and Abra Anderson’s start-up magazine, The Chicagoan—

—which unfortunately winked out of existence in about a year despite a strong start.

Next, Rick and Herman Kogan co-wrote “Yesterday’s Chicago,” a marvelously readable illustrated history. I’ll never forget how tickled I was to pick up a hardcover copy (with intact dust jacket) at Powell’s one day, and find I already had it autographed by father and son.

Then in 1977, Rick landed a spot on the Panorama staff under editor M.W. Newman—Herman Kogan had by then retired. The Panorama job lasted a whopping six months—all the way up to the Daily News’ last day on March 4, 1978. Luckily Rick moved over to the Sun-Times, and as we all know, left that paper with the Rupert Murdoch exodus, eventually landing for good at the Tribune. That’s not to mention the radio shows and the eight books, including the riveting “Everybody Pays” with Maurice Possley on mob hitman Harry Aleman.

And let’s not forget the countless shows that Rick has hosted, the speeches he rips off the top of his head. “He gave a memorial speech for a mutual friend,” consummate Chicago politico Don Rose told me recently. “It was another journalist, and it was so impressive I went up afterward and said, “I want you to give mine.”

Out of all that work, I’ve been thinking about “Yesterday’s Chicago” more and more as Rick’s Fuller Award approached, and this is why:

Between the Sun-Times and the Tribune, Rick has researched and written literally thousands of articles with one thing in common—Chicago. There are precious few Chicago topics I’ve researched that didn’t turn up a hit with Rick Kogan’s byline, always a treasured sight and key source material. Yet it wasn’t until I considered Rick’s career in its entirety that I finally realized what a downright baby he was when he wrote, as he himself would say, a goddamn history book. With his father, yes, but still, a goddam history book.

When Randy Albers interviewed Rick for his own piece in this program, Rick said, “I think that was during the time I was driving a cab, and my father said graciously, ‘Rick, do you want to help me with this book?’” Rick compared co-writing the book to “building a log cabin on the prairie” with his dad, even though he modestly referred to it as “basically a pictorial history”.

That kept coming back to me as I pondered early Rick Kogan. “Yesterday’s Chicago” is a pictorial history—but not in any kind of diminutive sense, only in that it’s both pictures and history. Split into several sections with concise overviews, each period comes alive in the curated photographs beside concentrated nuggrets of information, like historical multivitamins.

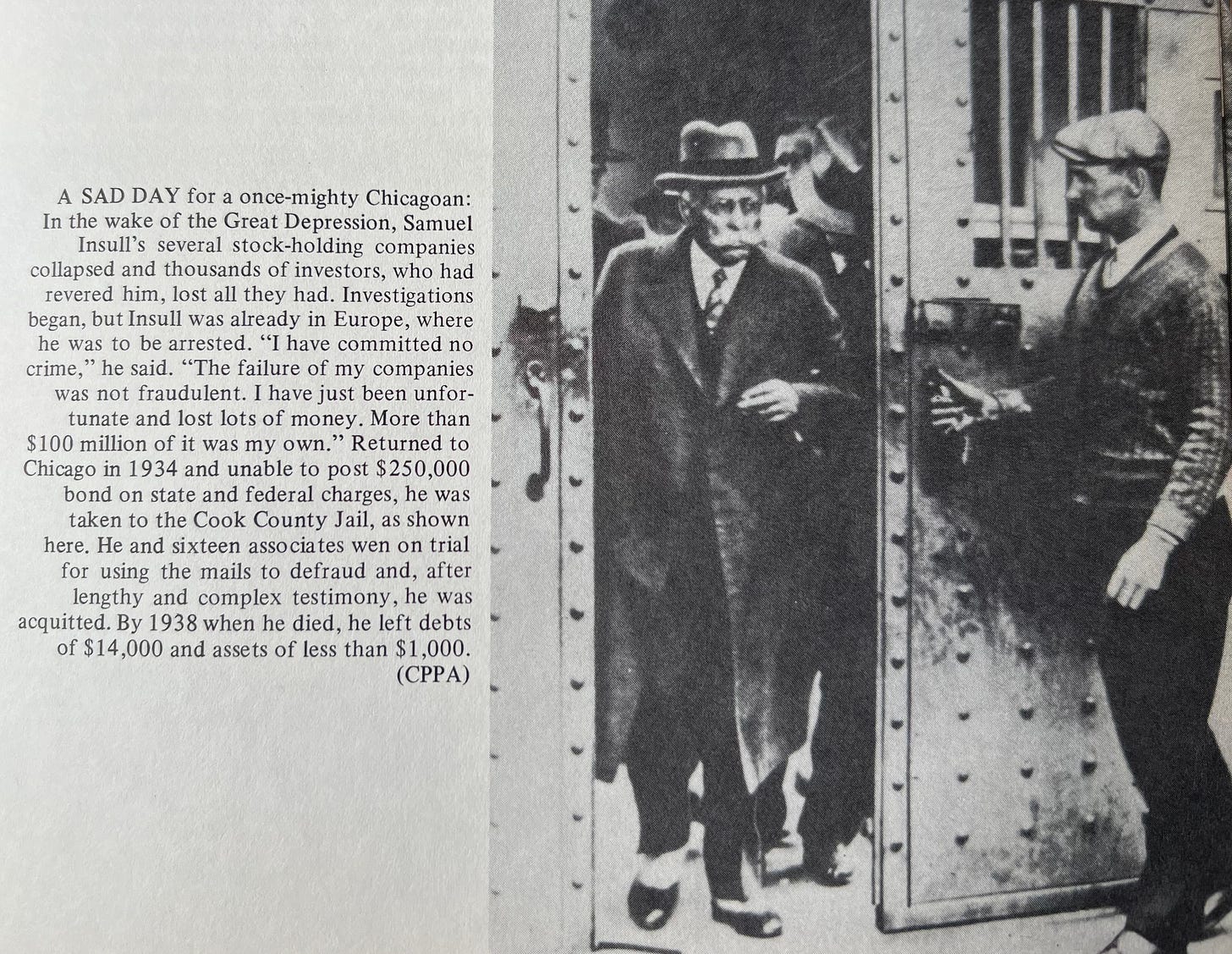

In “Yesterday’s Chicago,” the Kogans breathe life into previously flat, dead facts, like the collapse of Samuel Insull’s companies. Insull turns into a real person when you see him tentatively walking through a massive sliding steel door into Cook County Jail in his greatcoat, fedora and handlebar mustache.

Then there are the practically unknown and little-known incidents they wisely thread through the required historical milestones--balloon races, Big Bill Thompson’s rodeo in the City Council chambers, Wendell Willkie getting pelted with eggs at the La Salle Street train station during the 1940 presidential campaign. The Kogans didn’t throw that book together on the dining room table in a weekend. I mean, they may have used the dining room table, but not for just a weekend. Sifting through the facts alone, much less the pictures, would have been a gargantuan project. And we all know it’s easy to write long, but excruciating to edit down to the absolute essentials without losing the oddities and anecdotes that spark a reader’s imagination.

“Yesterday’s Chicago” is a solid log cabin, built from the ground up by a master craftsman and a talented apprentice. The log cabin, then, was a finishing school too, so that Rick took with him into his first newspaper job at the Daily News a unique, probably irreproducible blend of formal and informal training.

Which explains how Rick started with the Daily News in September 1977, and within a month his articles progressed from spritely, serviceable coverage of things like a coffee table book of George Lois’ ad campaigns and magazine covers, to painfully philosophical reviews of fading stars like Peggy Lee and Eddie Fisher.

“Peggy Lee is no longer an object of sexual fantasy,” Rick wrote of the older, heavy Peggy Lee performing at the Watertower Drury Lane.

There’s no sugarcoating Lee’s struggles after 30 years in show biz: “And yet there were moments when the years seemed to drift away; when the uneasy alliance of opulent splendor and intimacy of the theater combined with the grace of the lady’s singing and succeeded in discarding time….She still creates some beautiful moments. That may be all there is, but it’s more than enough.”

Rick’s review of Eddie Fisher reads like it comes from an author who’s gone through just as many marriages and drugs as Fisher himself: “His Friday night performance at a half-filled Blue Max was a sad glimpse at a man so tired and wasted from years in the spotlight that he appears, tragically, to be vanishing before our eyes….An odd and disturbing show, it is a combination of show biz without glitter and nostalgia without warmth….He merely exists, without the inventiveness or dynamic personality needed for a successful comeback….he seems ready, at any moment, to burst into tears….he is a dramatic portrait of all that is wrong with America’s passion for personality.”

By March 4, 1978, for the final issue of the Daily News, the kid—my God, he’s still a kid, just 26!—summons the gravitas to analyze how Chicago had changed during the15-year life of Panorama, which started in 1963 when Rick was 12.

As Rick pointed out in his lede, that day was both Chicago’s birthday, and the Daily News’ last day. “The Daily News has been here for most of those years to tell that astonishing and contradictory story,” he wrote. “And during the past 15 years we have watched things change, and change again. We have seen the architectural wizards transform the skyline, and in Chicago’s typically paradoxical way, we have seen the ghettos grow….We have seen fashionable near-lakefront neighborhoods revive themselves while Woodlawn burned itself out.”

“Look closely now,” he concluded. “Beyond the lakefront. Where is the city? It’s there, lurking in the corners behind the tall buildings, manifesting itself in small neighborhood groups that say, ‘Hey, wait a minute.’ The voices are there.”

“They almost didn’t run it,” he told me, because it was so bleak.

But you can always glimpse Rick’s optimism shining, however faintly, in the background. He’s always faced the ugly parts of his city straight on, and refused to stop loving it.

One of the bleakest days is still, for Rick and so many others, that final day at the Daily News. We talked about what the newspaper meant to him, and meant to the city, just as it got snuffed out in 1978. Rick summed it up in this story about his meeting, on that day, with a Polish immigrant cab driver:

“I’ll never forget the day the Daily News folded, I was taking a cab down to play I don’t know, fuckin’ racquet ball, with some friend from the paper. I’m in the cab, and the guy is a very deferential cab driver. I obviously said the Daily News building, and he’s driving down, and he goes, ‘I understand there won’t BE a Daily News tomorrow.’ And I said that’s true, as of tomorrow, Saturday’s the last edition. And he doesn’t say another word.

“He goes pulling into the delivery dock. I’m fumbling around for my money and he gets out and comes around and opens the door, and he’s crying. An older guy. He says, ‘Sir, I hope you work for the Sun-Times.’ I said no, I work for the Daily News. That’s OK, I’m fuckin’ 26 years old. And he goes, ‘I learned to speak English from reading that newspaper.’

Oh my God. And he was refusing to take my money.”

Rick loved the Daily News, and he loves Chicago, but Chicago didn’t love the Daily News enough for the paper to survive. A classic example of how this damn city will break your heart, and how Rick manages to portray Chicago, and Chicagoans, with a true love but with all the flaws intact.

Thanks, sweetheart, for all the words, written and spoken, about the city we all love.

Bonus Newspaper Materials

Remember, Rick is named for Riccardo’s. Fittingly, these Riccardo’s items were in the papers recently (by our standards here at this site).

Chicago Daily News

Sept. 16, 1972

October 1, 1972

Chicago Tribune Magazine

by Jack Star

“It is 8:02 p.m. at Riccardo’s, my favorite restaurant, on Rush Street near the Wrigley Building,” writes the Tribune’s Jack Star. “At the palette-shaped bar with its seven huge murals of the Lively Arts by famous Chicago artists, Rick is loudly singing ‘Come Back to Sorrento’ to an enthralled middle-aged couple, conventioneers from Dubuque. Outside, in the sidewalk cafe, four angry, young newspaper reporters are continuing (over a third martini on the rocks with lemon peel) their nightly seminar on the stupidity of their bosses. In the northern of the restaurant’s three rooms, Bruno, hovering over a chaffing dish, is miraculously transforming noodles, sweet cream, grated Parmesian cheese, and gobs of butter into fettucini a la Romana for a huge man—an offensive tackle for the Chicago Bears—who piously mutters his hope that the dish will be nonfattening.”

Riccardo’s is “a helluva place,” says Chester Kuttner, “an advertising executive who has been hanging around Riccardo’s for 25 years,” and Jack Star quite agrees, calling himself a newcomer as a “customer for only 20 years.”

The singing Rick in the lede paragraph is Young Rick, son of Old Ric Riccardo, “an Italian born ship’s cook who met Rick’s mother, a green-eyed, red-haired Irish girl, in New Orleans and jumped ship to marry her.”

The couple settled in Chicago, and so began a Chicago press haunt at that time as popular as the nearby Billy Goat, where Star notes the drinks are half the price. The first Riccardo’s was on Oakley Boulevard until after Prohibition, when Old Ric moved his business to the southwest corner of Rush and Hubbard.

“If you stand across the street and look at that ancient brick structure, you can see that it is really three buildings, one of them miraculously predating the Chicago Fire by man years,” writes Star. “The three buildings all held speakeasy-type nightclubs—the one at the corner of Hubbard Street was called Kelly’s stables in memory of its smelly origins.”

Within 15 years, Riccardo’s had taken over all three buildings, with Old Ric doing much of the work himself to knock down walls and create the paintings that became part of the Riccardo’s legend.

What about that palette-shaped bar, with its murals of “The Lively Arts”? Star writes that Old Ric got the idea because he hung art by WPA artists for free in the restaurant during the Depression. Ric did “Dance” himself, and the eager artists rendered the others.

Vincent D’Agostino painted “Painting,” Arron Bohrod portrayed “Architecture,” and William Schwartz imagined “Music.” Plus:

“You can see what Old Ric looked like in the caricatured face of the devil in Ivan Albright’s portrayal of ‘Drama’ (done in the same style as his evil ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’ in the movie of the same name).” In “Dance,” Old Ric used “his own severed ‘John the Baptist’ head, carried by Salome on a platter.”

Old Ric presided for decades, living in a “luxurious apartment” above the restaurant while a parade of prominent customers filed through, from John Barrymore to Don Ameche, besides the local press afficiandos and Chicago luminaries like Studs Terkel and Stuart Brent, plus Chicago Bears including Gale Sayers.

Jack Star describes a typical weekday lunch crowd: “Tribune columnist Robert Cromie rubs shoulders with Harry Weese, the famous architect, who rubs shoulders with Daily News columnist Sidney J. Harris and advertising agency head Ed Weiss”.

Young Rick grew up in rural Louisiana, since his mother and Old Ric had divorced when he was young. Young Rick returned by his 20s, “attending Roosevelt University by day and learning the restaurant business by night,” working every station from vegetable peeler to washing dishes and cooking.

Old Ric died while Young Rick was serving in Korea in the early 50s, and he returned to take over the restaurant. Young Rick had trained for opera at the Chicago Conservatory, and starred in a touring Army production of “Kiss Me Kate” with an orchestra. So Jack Star senses that Young Rick sometimes “feels that he really belongs more in show business.”

In 1972, Young Rick has played leading man to Betty Hutton and Betty Grable in Pheasant Playhouse productions of “Here Today” and “Born Yesterday,” but he confides to Jack Star why he can’t afford to pursue an acting career: He has two ex-wives, two alimonies, and five kids. So, Young Rick sings to conventioneers from Dubuque.

Riccardo’s was full of music, with opera singers dropping by including Vernon Dumke of the American Opera company, plus the nightly serenading from accordionist Roberto Rossi.

But Young Rick is also socially inclined. He just had to see the police riot in Grant Park in 1968. “Mike Royko and Bill Mauldin, the cartoonist, took me with them,” Young Rick tells Star. “We all three got tear-gassed—it was horrible what we saw.”

From there, Young Rick helped birth the Chicago Journalism Review, the wonderful though short-lived magazine that analyzed and criticized the city’s newspapers. The founders met upstairs at Riccardo’s hashing it out, spurred by their objections to the convention coverage.

That figures, Studs Terkel tells Jack Star: “For years Riccardo’s was just about the only downtown restaurant that would serve blacks. There was a plaque on the inner entrance door—it was stolen some time ago—that said something like, ‘We welcome all men of good will.’ And both Riccardo’s meant ALL men.”

Are there any Riccardo’s customers out there yearning for an old dish? This article includes the Riccardo’s recipes for Baked Lake Trout Livornese, Shrimp All Vesuvio, Chicken Vesuvio, Veal Scaloppine Al Marsala, Veal Scaloppine Al Limone, Chicken All Cacciatora, Pecan Pie Louisiana, Osso Buck All Toscana, and a gallon of beef stock. Drop me a line if you need one.

Oh what the heck—here’s one recipe:

Extra Credit:

According to Richard Ciccone’s Mike Royko biography, “A Life in Print,” Herman Kogan ate lunch at Riccardo’s most days, along with Daily News pals like Mike Royko and cartoonists Bill Mauldin and John Fischetti.

Per Ciccone, Royko worked on “Boss” mainly at the office on weekends.

“One Saturday afternoon in the summer of 1970 Royko finished the book and went to Riccardo’s, which was typically deserted on weekends, when only skeleton staffs manned the newsrooms that provides the restaurant’s clientele. Royko went to an empty bar and told the bartender he wanted a martini because he was celebrating. He had just finished a book.

“The bartender fixed the drink and then reached under the bar and proudly produced a Mickey Spillane paperback. ‘I’m almost finished with this one, too, Mike. I’ll give it to you when I’m done.’”

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.