The Great Chicago Reporter Rebellion of 1971, Part One

TCD1972 Special Edition: Electing Mayor Daley

To access all website contents, click HERE.

It’s 1971. As Mayor Daley finishes an unprecedented fourth term in office and campaigns for an unprecedented fifth, his political power appears—of course— unprecedented. Not to mention impregnable.

But 1971 Chicago newspaper reporters are ready for a fight. This is the forgotten story of how some reporters charged into political battle wielding their traditional 20th century weapon—the typewriter.

The battle scene: Mayor Daley is running for office yet again after a string of historic controversies—his “shoot to kill” order during the riots following Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination; the police riot in Grant Park during the 1968 Democratic National Convention; the 1969 Cook County State’s Attorney office’s predawn police raid on a Black Panther apartment that killed Fred Hampton and Mark Clark.

Yet all five Chicago daily newspapers in 1971 publish editorials endorsing Mayor Daley for a fifth term…even though they agree his opponent, independent Democrat-turned-Republican Richard Friedman, is terrific.

Reporters lob back their own editorials, printed as paid ads in two papers and as an op-ed in another—a singular journalistic coup d’état both then and now, over 50 years later.

As you’ll see, we can consider the Great Chicago Reporter Rebellion as both a battle between two institutional actors—Mayor Daley versus reporters—and as a civil war between newspaper publishers and their staffs. The reporters rebelled against the Boss, and against their direct bosses. There were internal divisions among the reporters themselves too, of course.

And like so many interesting ethical questions, you can argue every way ‘til Sunday over who was right.

Every great battle begins with reconnoitering the landscape and studying the combatants. So…sorry to make you wait for the real fireworks, but we’ll break it into four parts, starting here with the first installment. If you don’t know Mayor Daley, none of this makes sense. If you do know Mayor Daley, of course, you can wait for the last installment.

For the brave readers who venture into the fray now: Don’t worry, it’s not your father’s political primer.

Contents

Part One: Electing Mayor Daley (You Are Here)

A massive squad of political workers must fan across the city to find a way to elect Richard J. Daley mayor of Chicago for the first time in 1955.

Coming Soon

Part Two: They Were Expendable

Mayor Daley defeats more Republican foes in his second, third and fourth campaigns. Spotlight on the return of Ben Adamowski, Mayor Daley’s archenemy, for the 1963 campaign; plus quick skirmishes in 1959 (Timothy Sheehan) and 1967 (John L. Waner).

Part Three: Run Republican, Run Scared

It was actually Mayor Daley running scared in 1971, even though the Machine was still a fearsome unconquerable enemy. Former Democrat Richard Friedman runs Republican.

Part Four: The Reporters Strike Back

Armed with nothing more than typewriters, intrepid Chicago reporters enter the 1971 political field of battle.

Also:

I’ll warn you when we get there so you don’t twist an ankle.

The easiest way to make sure you don’t miss Part Two, Part Three or Part Four in the coming weeks:

“The mayor, legend has it, first appeared during the Chicago Fire of 1871,” wrote Mike Royko in 1968. “He doused the fire with one hand and milked Mrs. O’Leary’s cow with the other. Before the ashes cooled, he hired Frank Lloyd Wright to redesign the city, dug Lake Michigan to cool it, organized the White Sox and set aside land for two airports in case airlines were ever invented.”

Fittingly, you can’t beat the cover of “Boss” for an illustration of American Folk Hero Mayor Daley:

“Boss” is easily the most celebrated biography of Mayor Daley, written by the star columnist for the Chicago Daily News in a time when a handful of people got their pictures in the paper next to their work. There was no internet, no websites, no blogs or social media to compete with newspapers, though radio and TV were already whittling down print circulation numbers. Of those few writers in town whose names and faces appeared in the paper and made them local celebrities, Royko was a journalistic supernova whose work easily blotted out his competitors.

Royko’s tall tale in “Boss” sounded only a smidge bigger than average to 1971 ears. If you were around, you know that as well and deeply as the pattern of freckles on the back of your own hand. For Younger Readers who remain skeptical: Remember Johnny Appleseed was a real person too, and read on.

Young Richard J. Daley worked his way up through the Chicago multi-ethnic Democratic political machine first put together by Bohemian immigrant Anton Cermak, who used it in 1931 to crush Republican Mayor Big Bill Thompson…

…who’s best remembered now for giving the key to the city to Al Capone.

Big Bill’s campaign song that year declared, “I won’t take a back seat to that Bohunk.” Thompson also called his opponent “Pushcart Tony,” since Cermak had started out as a pushcart peddler.

For Younger Readers: “Bohunk” was a then-common slur for Bohemians, extended to the entire burgeoning horde of various Slavs coming to these shores. It would be shortened to “hunky” and may be the origin of “honky.” Let me tell you, my Polish immigrant Gramma did not appreciate the word. She was being called “hunky” at precisely this time—though she found it especially galling coming from other Poles who had been here longer and looked down on her accent. “I said, ‘I’ll show them who’s a hunky,’” she told me once, in a story about some mean girlfriends who were stuck up because they were more Americanized. I was only surprised by Gramma’s story because “hunky” had gone out of fashion by the 1970s when Gramma told me about it. At that time, I thought everybody called us “Polacks,” since the world was then awash in stupid Polack jokes. If you’ve ever watched “All in the Family,” it was pretty realistic. Anyway:

“Bohunk” wasn’t a long-term winning strategy in a city of newcomers. The headline below tells the story, but don’t miss the cartoon version of Pushcart Tony running over Big Bill.

Anton Cermak won by nearly 200,000 votes. “Thompson…was the worst beaten candidate in the history of the municipality,” noted the Tribune.

Republicans have yet to wrest back the mayor’s seat as of 2023.

Chicago’s Democratic Machine would finally begin clanking and sputtering with the ongoing loss of patronage jobs (government jobs contingent on getting out the vote) due to the Shakman decrees starting in 1972, and Mayor Daley’s death four years later. But young Richard J. Daley came up in the Machine’s heyday.

Besides political offices, the Machine at its peak controlled about 40,000 patronage jobs to reward the little people who got the politicians elected in exchange for collecting government paychecks, according to Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor’s mammoth, well-written biography “American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley: His Battle for Chicago and the Nation.”

That’s a lot of hands ringing a lot of doorbells…and whatnot.

Born in 1902 into Chicago’s ancestral mayoral neighborhood of Bridgeport on Chicago’s South Side, just north of the massive Union Stockyards, Daley came from an immigrant Irish family. He grew up in an apartment at 3602 S. Lowe, then lived his entire adult life one block north in a classic Chicago bungalow at 3536 S. Lowe with his wife, Eleanor “Sis” Daley, née Guilfoyle. They raised seven children there.

Daley was baptized at Nativity of Our Lord Roman Catholic parish just two blocks away at 37th and Union, where he also attended grammar school, made all his sacraments, served as an altar boy, attended mass almost daily as an adult…

…and left this world from the church steps in 1976.

In “Boss,” Mike Royko makes fun of early Daley PR that made him out to be a cowboy at the Stockyards. “For years, the legend goes, he herded cattle during the day then dragged himself to law school at night,” writes Royko. Instead, per Royko, Daley was certainly riding a desk at the Stockyards using the secretarial skills he learned at De La Salle Institute, then a three-year technical high school aimed at placing graduates in office jobs.

Or, according to Daley’s later political archenemy Ben Adamowski: “That is just so much bull. He got on a public payroll almost as soon as he was able to vote, and he’s been there since.”

But other biographies say Daley at least herded cattle in the morning. Per Bill Gleason’s “Daley of Chicago”: “Young Daley…found a job with Dolan, Ludeman & Company, a commission house…in the Stock Yards…The Mayor is proud of his years with Dolan, Ludeman. He had to be up at 4 a.m. to walk to the Yards from his parents’ home at 3602 South Lowe Avenue. In the early morning hours he was on horseback, helping to move cattle from trucks to pens to the ramps that led to the slaughterhouses in the noxious Yards. When the ‘roundup’ was finished, Dick went into the office, where he used the skills he had acquired at the Institute.”

Either way, Daley did take “pre-law classes” and got his law degree via night school, all from DePaul.

Royko and other biographers note that like many immigrant young men, Daley belonged to a “social club” that probably doubled as the kind of street gang that beat up outsiders who wandered into the neighborhood. If Daley didn’t participate in the notorious Chicago race riot of 1919, wrote Royko, “it is certain that some of his friends” in the Hamburg Social and Athletic Club did.

The Hamburgs were young Daley’s gateway drug to the Machine, because an older Hamburg president had already gone into politics—first as alderman and eventually Congressman. Daley became a Democratic precinct captain, then ward secretary, with a clerking job in City Council—besides serving as Hamburg president himself for 15 years, starting at age 24.

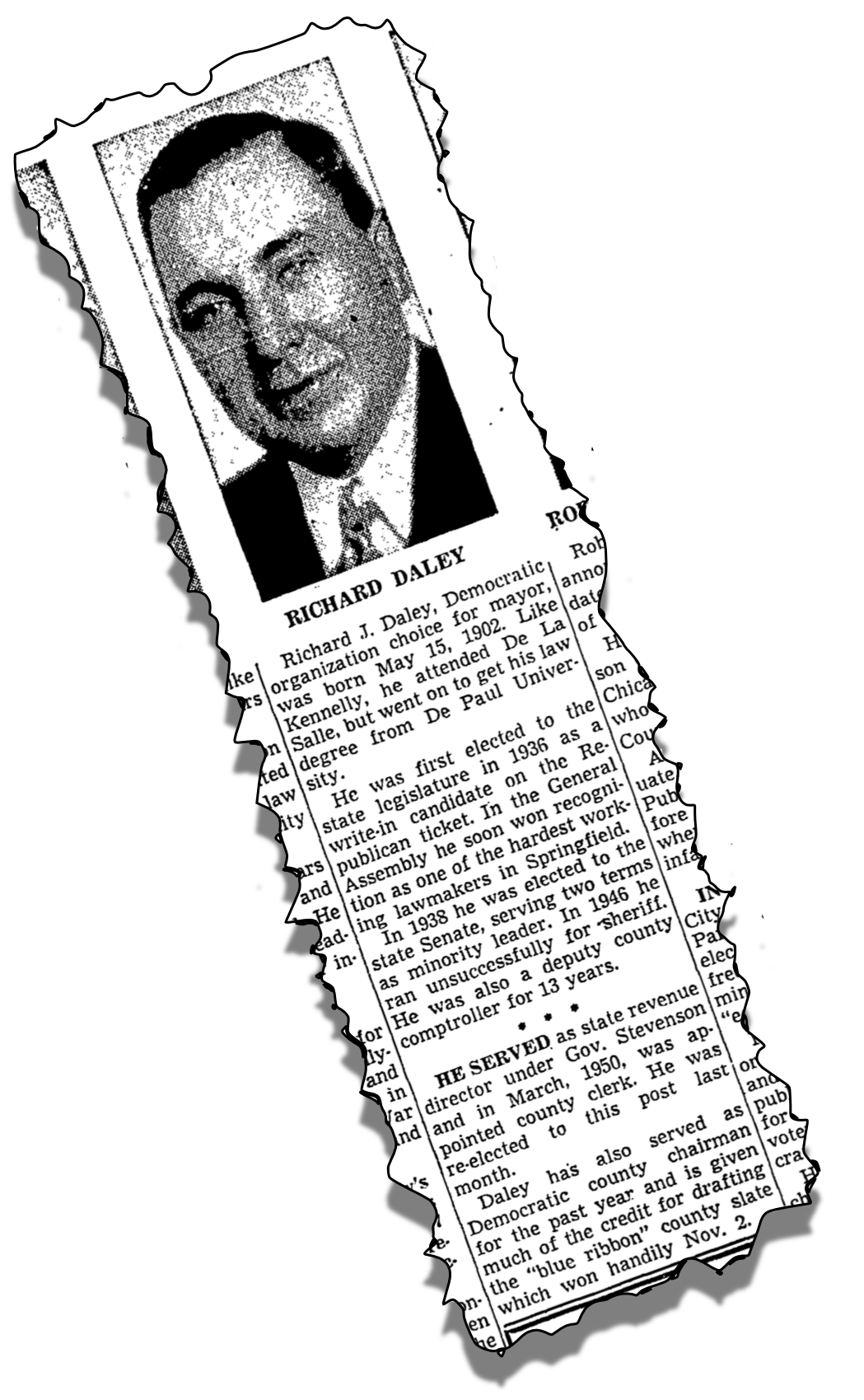

Here’s Daley’s political history from the Daily News during his first mayoral campaign:

Note the recurring early press theme that Daley is “hard-working,” which comes up often in Daley’s premayoral years along with “intelligent.” Why?

Daley earned the “intelligent” part by working diligently in financial positions such as deputy Cook County comptroller. Biographers agree that Daley the student was remembered as dutiful, not notably bright. But Daley the politician was deeply schooled in all the math necessary for budgets and government finances, clearly outweighing his lack of language skills.

Plus, respectable Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson II appointed Daley state revenue director, distancing Daley from his Machine roots. Stevenson “became so enamored of his state revenue director that he inscribed a framed picture of Daley, Sis, and the seven children with a bold pen: ‘To Dick Daley, God love him!’” according to Len O’Connor’s “Clout: Mayor Daley and His City.” Daley hung it behind his desk in the State of Illinois Building, then kitty-corner from City Hall.

As for “hard-working,” reporters knew Daley personally walked the straight and narrow, focusing on work and eschewing normal political activities like graft and girlfriends. Reporters knew this because back then, legislators didn’t have to hide their carousing from the press. The reporters frequented the same bars, and Daley wasn’t there.

Daley briefly lost his “hard-working-intelligent” media sheen with a run for Cook County Sheriff in 1946, his only unsuccessful campaign. At that point, the papers pegged him as “the tool of” Mayor Ed Kelly, per Royko in “Boss.” But Daley got his sheen back and well-buffed soon afterward by working for Gov. Stevenson.

Younger Readers, don’t underestimate the value of Daley’s association with Adlai Stevenson. Did you know Peter Sellers based his portrayal of President Merkin Muffley in “Dr. Strangelove” on Stevenson? He did, because Muffley was the one guy in the movie who was supposed to be a good, rational, ethical, moral character.

If you didn’t read Daley’s pre-mayoral newspaper clip above, here’s the digest: State representative, then state senator, deputy Cook County comptroller, state revenue director, Cook County Clerk, and finally, most important of all, chairman of the Cook County Democratic Organization—aka, the Machine.

Does that sound easy? The Machine obviously made it possible, but no—not easy. Daley’s seemingly unassailable power in 1971 was a battlement that truly took hard work and years to cement in place, with more construction delays and setbacks through four mayoral campaigns and terms, starting in 1955.

The Machine made Daley’s political rise possible by pushing him up through the ranks as new jobs opened, often through deaths which proved serendipitous for young Daley. Even Daley’s ascent within the Machine depended on death, particularly the all-important Democratic chairmanship. That position would almost certainly have gone to Judge James McDermott, former 14th Ward Alderman as well as Cook County Treasurer. Key McDermott backer Clarence Wagner, the then-current 14th Ward Alderman, even stopped the initial Democratic Central Committee vote to put Daley in the chair. But then McDermott went on a fishing trip and got killed in a car accident.

Convenient deaths aside, Daley’s “hard-working” image was definitely true—starting with Catholic school, as any former Catholic student can tell you. According to “American Pharaoh,” it took Daley ten years of night school while working full-time to earn his law degree. Imagine that schedule, all the while toiling on ward matters and campaigns at the 11th Ward Democratic organization; serving as president of his Hamburg social club; and managing the Hamburg baseball team.

Hamburg team manager was a deceptively important role since the club played for what was then big money in side bets, per “American Pharaoh.” As one former Hamburg team member told Gleason, “Dick often came to practice carrying books. He was either coming home from classes at DePaul or going down there. He was a very busy guy, but he took his job as manager seriously. He made the lineups, booked the games, and ran the team on the field during games.”

Later, the patronage jobs that fueled the Machine’s political army had to be managed. As mayor, notes “American Pharaoh,” Daley met with all 50 ward committeemen to dole out the jobs, using prepared tabulations “of how each precinct in each of the fifty wards had performed in the last election—more than 3,000 separate vote tallies that Daley personally pored over in making his patronage decisions.”

Not everybody saw it that way. According to Daley’s archenemy Ben Adamowski, “He made it through sheer luck and attaching himself to one guy after another and then stepping over them.”

1955: First shots in the primary

Daley’s first run for mayor began with a tricky maneuver, required because the Machine had backed itself into a corner. Here’s what happened:

Machine founder Mayor Anton Cermak had died in 1933, just a few years after making it to City Hall. Cermak accidentally took an assassin’s bullet meant for president-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt, while sitting in an open convertible with FDR in Florida. There’s a story that Cermak was the real target, a mob hit, that is likely an early version of JFK conspiracy theories. We’ll go down that rabbit hole some other time. Cermak died, is the crucial point now.

The Machine dropped Bridgeport-born Ed Kelly into Cermak’s empty fifth floor seat at City Hall.

Mayor Kelly found three ways to “nurture” the toddler Machine, Roger J. Biles explains in “Richard J. Daley: Politics, Race, and the Governing of Chicago”: federal money from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal; luring Chicago’s Black voters away from Republicans; and collecting money from the mob, or “syndicate” as it was called in Chicago.

“By allowing the free operation of gambling, prostitution, and other forms of vice in his city, Kelly made Chicago a ‘wide open town’ and obtained more of the ‘grease’ necessary to keep the political machine operating,” writes Biles.

In other words, Kelly found it expedient to take some cues from pre-Machine Mayor Big Bill Thompson. Sounds like Chicago wasn’t “shut down” for very long.

In “Clout,” Len O’Connor claims “an educated guess” is that the mob paid about $20 million yearly during Kelly’s 1933-1947 mayoral reign, “for the unharassed operation of horse books and gambling joints,” plus “whoremongering, the numbers…syndicate-controlled slot machine operations, and other such illegal pleasures.” $20 million 1947 would be about $273 million in 2023.

Like Big Bill’s Capone-friendly days, the Machine sensed Kelly’s corruption was wearing out its welcome among voters. The city’s high schools almost lost their accreditation under Kelly. Plus, some white voters didn’t like Kelly’s support for integrated housing.

So in 1947, the Machine installed boring Bridgeport-born businessman Martin Kennelly as a reform replacement, in order to look like it was cleaning up its own house.

“Running a reformer was risky,” Royko notes in “Boss,” “because he might take things seriously and run amuck, but it would be better to have their own reformer than a Republican reformer, because they could get rid of their own when the time was right.”

Enter Martin Kennelly, who was just as dynamic as he looks here.

Two terms later, Mayor Kennelly had done his janitor’s job—too well in fact. Though the newspapers did criticize Kennelly, he was generally seen as a good-government type for running a clean city purchasing department and a civil service board that replaced about 12,000 temporary political jobs (Machine patronage jobs, that is) with permanent civil servants not obligated to campaign for Machine candidates in order to pay rent and buy groceries. Many of those “replaced” temporary jobs belonged to Democratic precinct captains, noted the Tribune, which “aroused the wrath of Democratic machine leaders”.

After eight years of Kennelly’s political scrubbing, Chairman Daley felt the Machine’s house was spic and span. But how to get the keys back? Daley had to choreograph the dumping of Mayor Kennelly. It all began with the slating.

For each election, the Cook County Democratic Organization formed a “slating committee” to interview candidates who wanted to run in the Democratic primary with the Machine’s backing. Chairman Daley now appointed all the slating committee members. The committee Daley chose then selected a “slate” of candidates, one for each office, from aldermen to mayor. Then the Machine—the 50 ward committeemen, directing their precinct captains and legions of patronage workers—campaigned for the slated candidates; the slated candidates won the Democratic primary and became nominees; and the Democratic nominees won the wild majority of general elections.

So the first step, the slating, was key.

Don’t miss the latest breaking stories from 1972, right here!

Daley biographies all describe how the 1955 slating committee swept Mayor Kennelly out the door. It was no secret at the time. The Machine leaked stories to the press about how Machine officials and allies didn’t want Kennelly, playing it as a groundswell to slate a supposedly reluctant Daley instead.

Daley played coy throughout, refusing to say if he’d run. But he didn’t attend the opening of Kennelly’s campaign headquarters, held just before the slating committee meeting—nor did any of the slate makers.

You don’t use Santa and his flying reindeer as an excuse if you want to fly under the radar.

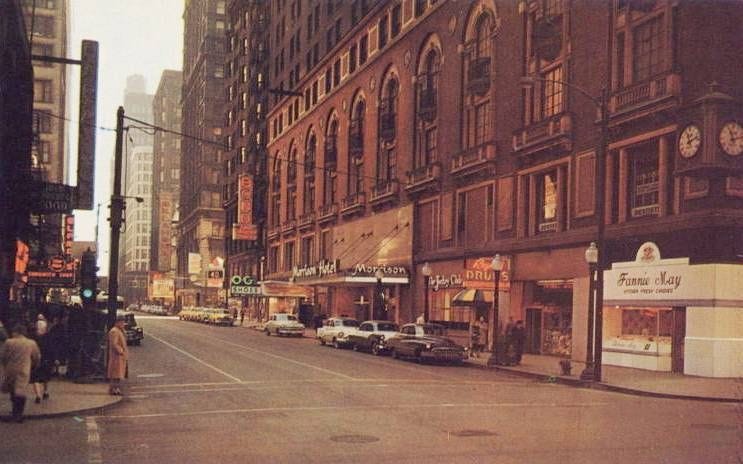

When the time came, the slating committee listened to Mayor Kennelly’s six-paragraph prepared statement in the Machine’s offices, then in the Morrison Hotel at Madison and Clark—replaced by today’s Chase Plaza. “Morrison Hotel” in this time period is shorthand for “Machine.”

Nobody asked any questions, nobody shook hands, and Kennelly left.

“That was short shrift?” asked a reporter waiting outside in the corridor.

“It was,” Kennelly answered.

Some accounts describe the exiting Kennelly as “pale and shaken”. Later in the campaign, when he’d had time to get brave again, Kennelly talked tough to a campaign rally: “I went over there to the Morrison hotel and they gave me a fast deal,” he declared. “I thought that was the way it would be, but maybe not that crude. I thought I was in a deaf and dumb show.”

A few days after “interviewing” Kennelly, the slaters “drafted” Daley for mayor.

The 50 ward committeemen confirmed the choice, 49-1.

The one guy who sided with Kennelly would lose all his people’s patronage jobs, and eventually end up in jail.

Mayor Kennelly issued a blistering statement: “The phony ‘draft’ is over. The question is whether the people of Chicago will rule or be ruled by the willfull, wanton inner-circle of political bosses at the Morrison Hotel….The nominating committee was selected by the county chairman (Daley). He sat in at its sessions. Who engineered the ‘draft’ that resulted in his endorsement?”

The move didn’t go over well on the editorial pages, before…

…or after.

Note that the editorial writers seem to twist themselves in linguistic knots to both blame Daley, and not blame him—to put it on “the organization backing Daley,” when Daley was the head of the organization backing Daley. Still, it wasn’t a good look.

Daley found it necessary to claim immediately, in his speech to the slating committee accepting their backing, that he wouldn’t “sabotage” Kennelly’s Civil Service Commission, or fire the head of Kennelly’s purchasing department.

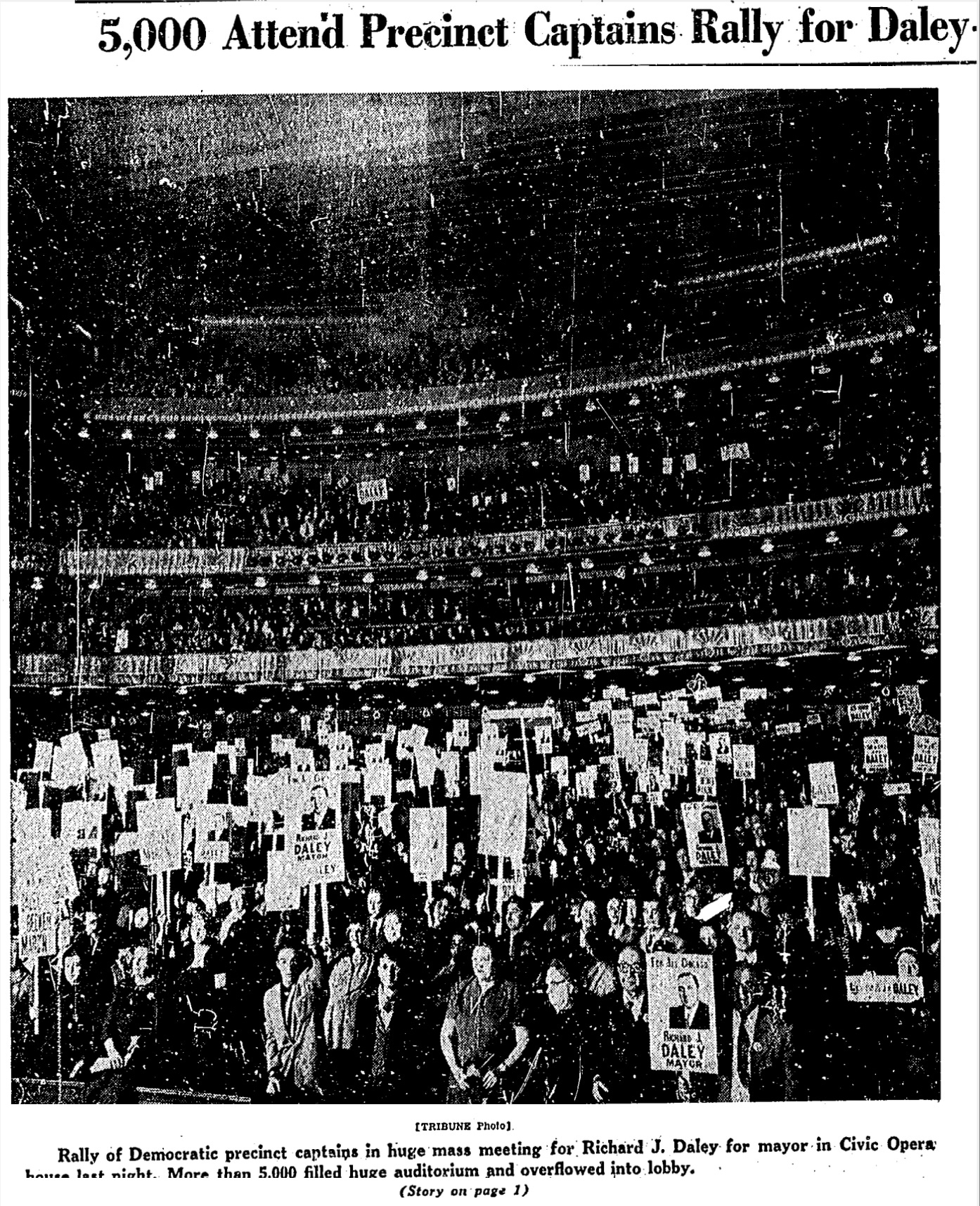

A few weeks later, Daley told an overflow crowd at a gigantic precinct captain’s meeting at the Civic Opera House: “My opponent says, ‘I took the politics out of the schools; I took politics out of this and I took politics out of that.’ I say to you: There’s nothing wrong with politics. There’s nothing wrong with good politics. Good politics is good government.”

Technically, George Orwell’s “1984” had been published five years earlier, but Daley was not a big reader of literature. As Mike Royko notes on the first page of “Boss,” Daley’s home bookshelves “hold religious figurines and bric-a-brac. There are only a few volumes—the Baltimore Catechism, the Bible, a leather-bound Profiles in Courage, and several self-improvement books.” So Daley almost certainly came up with his Newspeak Opera House speech all by himself. “Good politics is good government” would become recognized through the years as Daley’s main slogan.

Machine Chairman Daley was now running in the Democratic primary against two formidable anti-Machine candidates—Mayor Kennelly, and ambitious attorney Ben Adamowski, fast becoming Daley’s archenemy.

Adamowski, per Gleason’s “Daley of Chicago,” guessed wrong that Kennelly would fold and drop out. “I didn’t think Kennelly would run, and if he did declare, I didn’t expect him to stay in,” Adamowski told Gleason. “My experience with him was that in a contest, he’d back off.” So much for Adamowski’s plan to win by joining Chicago’s huge Polish community with Kennelly voters.

Adamowski mirrored Daley in many ways—incredibly ambitious; DePaul law school grad; known for being strait-laced in the bawdy political world of Springfield while serving in the legislature; quietly married with kids, two sons; the kind of regular guy who lived in a modest family neighborhood home (1647 N. Nagle)—so regular that he had a basement workshop and had sliced off the tip of a finger there with a planer.

Oh, but their differences. Adamowski had strayed from the Machine early. And unlike Daley, he was a glib, eloquent speaker, the kind of guy who gets better with rage rather than turning all shades of spluttering red and purple.

Here’s the skinny on Adamowski from the Daily News:

The 1955 Democratic mayoral primary was some three-way.

Let’s see:

Daley had politically stabbed Kennelly in the back, after Kennelly had often helped Daley in the past, including slating him for his then-current office of County Clerk before Daley ascended to the Machine chairmanship.

Adamowski and Daley were former friends turned archenemies. Adamowski befriended Daley during their days together in the Illinois legislature. Per many sources, including Adamowski himself, they often took long walks around Springfield together to unwind along with fellow legislator (future judge) Abraham Lincoln Marovitz, because they were some of the only guys who didn’t use their long days and nights away from home to basically lead a double life. “The Three Musketeers in Springfield were Daley, Marovitz and Adamowski,” Gleason quotes Adamowski.

But by 1955, Adamowski was an implacable Machine foe. His former friend Dick Daley had become Machine Chairman one year earlier. Seriously, isn’t this a Scorcese film?

And then there’s the Adamowski-Kennelly leg of the triangle. Adamowski had served three years as Kennelly’s first corporation counsel—Kennelly’s first appointee in fact—and then quit. Why?

Depending on the source, either Kennelly didn’t give Adamowski the necessary backing to get slated for the 1950 Democratic nomination for U.S. Senator, after Adamowski had his ballot petitions all printed up; or Adamowski was disgusted with Kennelly for not standing up to the Machine enough.

Probably a bit of both. Everybody is clear: The City Council and the Machine ran Chicago during the Kennelly years.

“Dollarwise, [Kennelly] was one of the most honorable men I have known,” Gleason quotes Adamowski from a 1969 interview. “But my argument—to his face—was that he was morally dishonest, because he let the boys at Democratic headquarters use him as a front.”

But Mayor Kennelly still had pull in the slating process before Daley ascended to the Machine chairmanship, and it looks like Kennelly kept Adamowski from running for the Senate in 1950. Adamowski dropped his Senate dreams after a two-hour meeting with Mayor Kennelly.

“I wasn’t being coy about it,” Adamowski told a reporter afterward about his decision to (not) run for the U.S. Senate. “I had been unable to give my answer until I had had the final discussion with the mayor.”

A year later, Adamowski threatened to run as an independent in Kennelly’s 1951 mayoral re-election campaign, only relenting because he said his own surveys showed his candidacy would get the Republican elected.

During the 1955 primary, Adamowski enjoyed attacking his old friend and his old boss at the same time:

“After eight years [Mayor Kennelly] says that, if reelected, he will get rid of the men in the Morrison hotel,” Adamowski told reporters. “Now he is telling the truth about the men with whom he has been associated, but he is telling it only because they refused to indorse him for a third term.” (That’s Tribune owner/publisher Col. Robert McCormick misspelling “endorse,” not me.)

“When politicans fall out, honest men get their just dues,” Adamowski quipped at a League of Women Voter’s primary forum, referring to charges that Kennelly and Daley had been flinging at each other. “I agree with what these two candidates are saying about each other.”

Personal beefs aside, all three men wanted the top job in the second largest city in the most powerful country on Earth. Of course it got ugly.

It was the kind of campaign that unabashedly stooped to juvenile pranks, like when Daley’s Machine flunkies snuck his voter petitions in a literal back door of the city clerk’s office to beat Kennelly’s guy, who was waiting at the clerk’s door the day petitions were accepted. The candidate whose petitions made it in the door first got top billing on the ballot. Kennelly’s guy brought in his petitions when the city clerk’s doors opened and got them stamped “8:18. a.m.”

“His men smiled,” writes Royko in “Boss. “Just then, somebody noticed another mail bag, outside the private office of the city clerk…stamped ‘8:13 a.m.’ In it were Daley’s petitions.”

That’s the same story repeated in Biles’ “Richard J. Daley” and in Cohen and Taylor’s “American Pharaoh,” but Gleason insists it was “the version accepted by the press, but the old fellows in the big fedoras with the broad brims turned up all around told stories of how easy it is to turn back time when it is being kept on a stamp.” (The “old fellows” are the “City Hall types” Gleason describes early in his book, groups of Machine flunkies with nominal jobs in their wards who hung out at City Hall all day, whose “most essential item of apparel was a wide-brimmed fedora…worn squarely on center” with “the brim…upturned all around.”)

Later in the campaign, according to O’Connor’s “Clout”: “Some registered Democrats in the low-income areas reported that they had found envelopes containing dollar bills in their mail boxes, together with a message that said, ‘This is your lucky day. Stay lucky with Dick Daley.’”

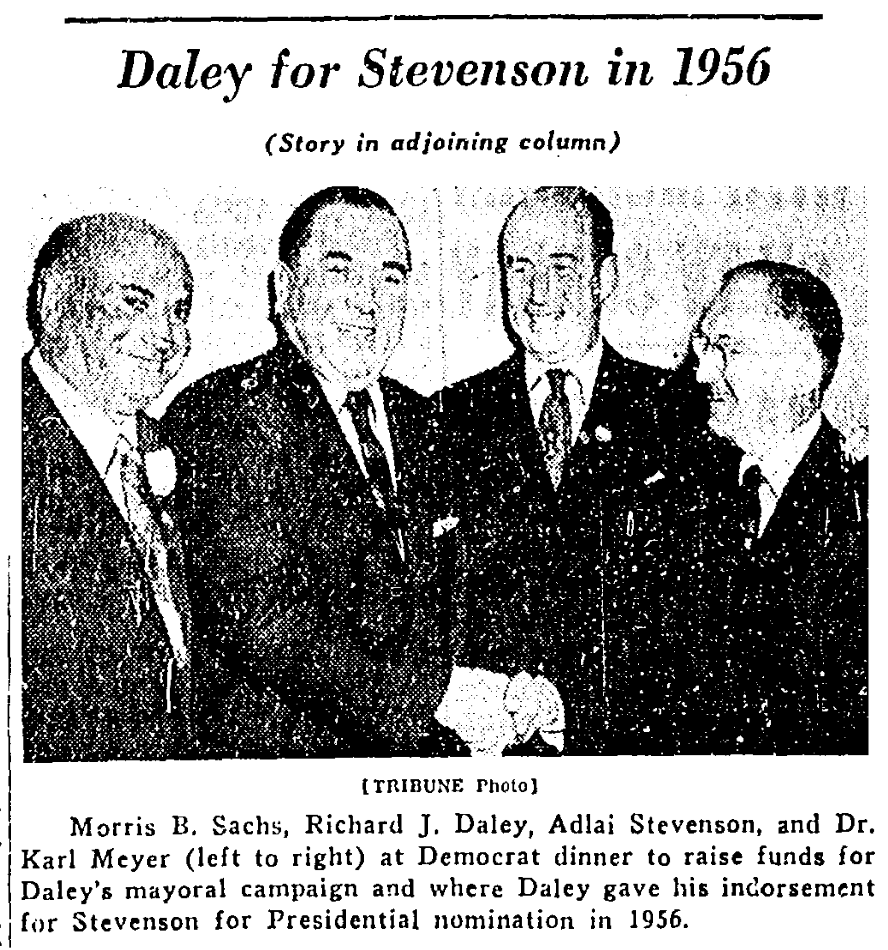

Oh, and Daley got now former Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson to formally endorse him.

“The Chicago Machine had launched Stevenson’s political career, and he would need its backing when he sought the 1956 Democratic nomination for president,” write Cohen and Taylor in “American Pharoah.” “Win or lose in the race for mayor, Daley would be the head of the machine when that decision was made.”

Another equally valuable endorsement came from Illinois’ esteemed U.S. Senator Paul Douglas, former 5th Ward Alderman and certainly the only former member of the Chicago City Council to ever appear on the cover of Time Magazine, not once but twice. Paul Douglas was dubbed “the conscience of the Senate.” Martin Luther King Jr. once called Douglas “the greatest of all senators”. Look at him. He looks like Spencer Tracy, for God’s sake. And yet, the Machine got Douglas elected, which technically makes Douglas part of the Machine, which then elected Daley.

Because Daley and his Machine won the primary, of course. His opponents’ constant and obviously true accusations of bossism couldn’t quite stick. It didn’t matter that Daley’s campaign message was weak and internally inconsistent, as he implicitly approved of Kennelly’s performance by insisting he’d stick with Kennelly’s good government programs.

The Machine won. Daley won. Daley was the Machine now, as surely as if he was a bionic politician.

Again, was that easy? No, it was hard Machine work. Machine lunches, Machine rallies, Machine parades. Machine…whatnot. Polls actually showed Kennelly beating Daley close to the primary Election Day. But in the end, Daley won by about 100,000 votes, with nearly the entire margin of victory coming from the Machine’s “Automatic Eleven” strongest wards, including U.S. Rep. William Dawson’s five Black “submachine” wards, and the mob-controlled 1st ward.

We will see Ben Adamowski again as Mayor Daley’s story continues, unlike Mayor Kennelly.

Chicago Trivia Rabbit Hole Straight Ahead

Remember Stephen Hurley, president of Kennelly’s civil service commission, lauded by the papers for replacing 12,000 Machine patronage jobs with protected civil service employees? With Kennelly’s primary loss, Hurley tendered his resignation effective at the end of Kennelly’s term.

“Informed of the development Ald. [Paddy] Bauler [43], a Democratic wheelhouse, danced a jig and said: ‘This is victory No. 1, Chicago isn’t ready for reform yet,’” reported the Tribune. Boldface added.

This is possibly the most famous quote in Chicago political history, so it bears some study.

First, Paddy Bauler did not in a million years say “isn’t.” He could not have said “Chicago isn’t ready for reform.” Bauler was one of the last bar-owner aldermen, spending most evenings behind the bar himself or carousing with the customers. Here he is on his 65th birthday, during the 1955 mayoral primary. “When not singing, Bauler lavishly praised Richard J. Daley, Democratic machine candidate for mayor,” per the Tribune. “He told newspaper reporters that ‘Chicago papers should be on their guard against those phony reformers’.”

Newspapers usually cleaned up quotes at this time, unless they wanted to mock someone for ungrammatical speech. So Paddy Bauler’s real quote is certainly that most famous and infamous of Chicago political phrases so well known and repeated ad infinitum:

“Chicago ain’t ready for reform!”

(The ‘yet’ was quickly dropped.)

That’s a good bit of trivia in itself, but we’ll go one better: Somehow, the story handed down in Chicago lore has been that Paddy Bauler first uttered this immortal phrase when Richard J. Daley won his first mayoral election later that April. If so, Paddy Bauler would have been talking about the defeat of Daley’s upcoming Republican opponent in the general election, Robert Merriam. But as we saw just above, Bauler actually put his indelible stamp on Chicago history on February 23, when a Tribune reporter told him about Civil Service Commission President Stephen Hurley’s resignation, after Mayor Kennelly’s defeat in the primary.

We should add that Paddy Bauler is credited in most Daley biographies with following up his most famous line with another quotable bit of wisdom, naming other Machine leaders at the start of the quote:

“Keane and them fellas—Jake Arvey, Joe Gill—they think they are gonna run things. Well, you listen now to what I am sayin’: they’re gonna run nothin’. They ain’t found it out yet, but Daley’s the dog with the big nuts, now that we got him elected. You wait and see; that’s how it’s going to be.”

The entire quote, starting with “Chicago ain’t ready for reform,” is attributed in later biography footnotes variously to the Chicago Tribune on April 6, 1955 (the day after the general election), as quoted in Len O’Connor’s “Clout”; a New York Herald Tribune article in 1960; a Time Magazine article from April 7, 1955; and from Eugene Kennedy’s 1978 Daley biography, “Himself! The Life and Times of Mayor Richard J. Daley.”

But as far as I can see, Paddy Bauler isn’t quoted in the Tribune on April 6 at all, about anything.

O’Connor doesn’t give any attribution in his own text or footnotes. I don’t see the quote in Time Magazine. Some biographies say Kennedy’s “Himself!” cites the Tribune on 4/6/55, but the quote just isn’t there. Even if it was, it would have been a repeat, since it had already appeared in the paper on 2/24/55. Kennedy uses Bauler’s famous quote after Daley thrashes Robert Merriam in the general election, but he doesn’t give it any attribution at all. And his book has no footnotes.

All signs point to Bauler’s famous phrase getting moved understandably from post-primary to post-election. And it happened quickly. Already in 1959, a Sun-Times editorial on the election of already-notorious Paul Powell as speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives notes: “Both Paddy and Paul have contributed much to the enrichment of Illinois lore and language. Who will ever forget Paddy’s jubilant jig after the local Democratic machine triumph in 1955 and his loud crowing that ‘Chicago ain’t ready for reform yet’?”

The “yet” is still there in the January 9, 1959 editorial, but the true context—that defeating incumbent Democrat Mayor Martin Kennelly and his Civil Service Commission was the initial Machine triumph in 1955—is gone.

We know Bauler definitely said it first post-primary, so the question is, did he say it again after the general election, given how much everybody loved it the first time? That would make sense. The guy obviously enjoyed attention. Except I don’t see this quote in any of the newspapers on 4/6/55, or soon afterward, either.

So when did Paddy Bauler say the great line about Daley being the dog with the big nuts? At this time, unknown. I’ll continue looking into it.

Now let’s climb out of the rabbit hole and get on to the general election.

On to the general—election

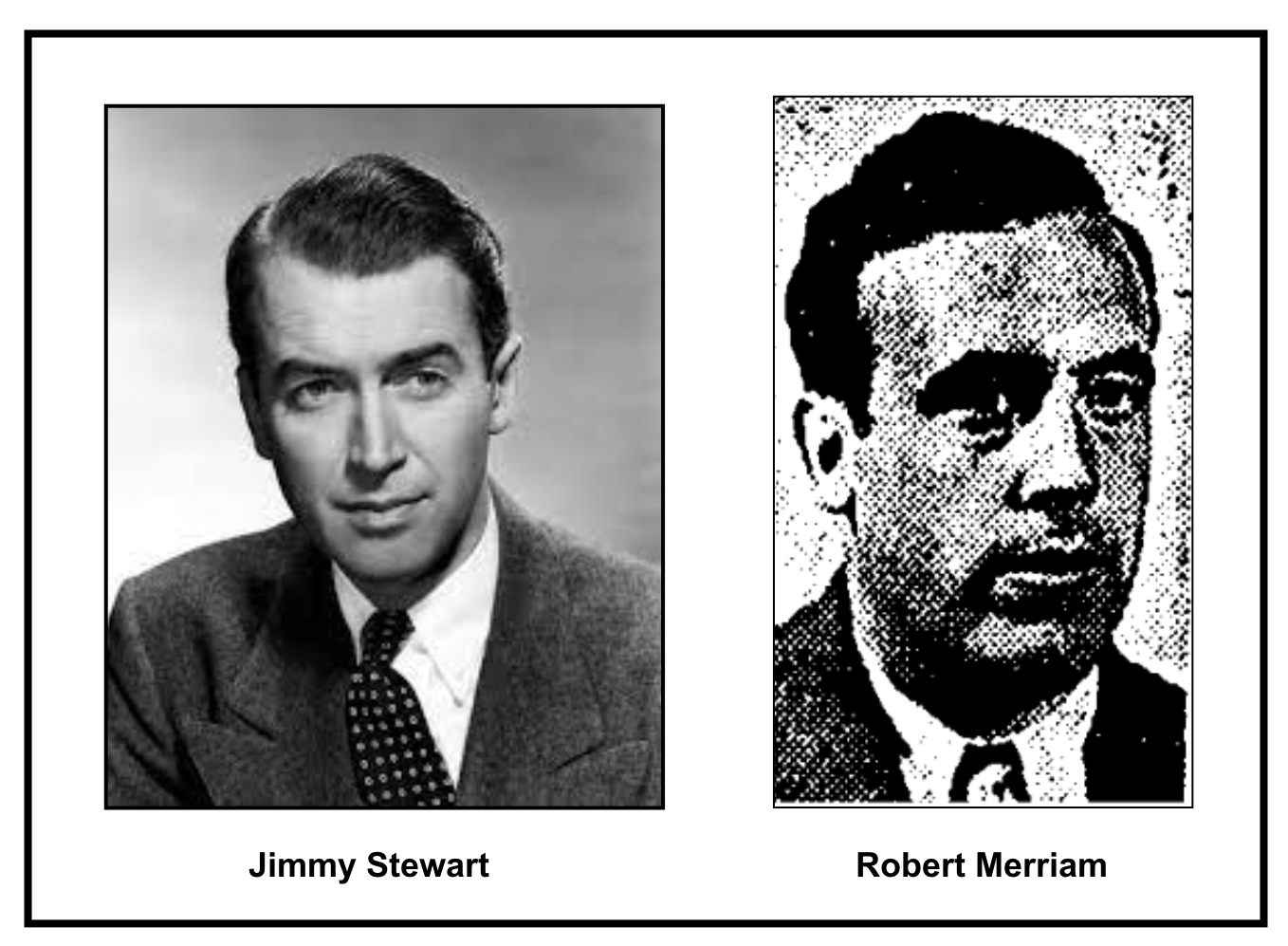

In the general election, Daley was a jowly Machine politician running against a young, handsome and articulate war hero—5th Ward Ald. Robert Merriam.

“A splendid orator, good-looking, knowledgeable, energetic, and youthfully mature, Merriam would have been expected to crush Daley in any city but Chicago,” observed Royko in “Boss.”

Merriam, son of renowned University of Chicago professor and former 5th Ward Ald. Charles Merriam, was proofing his memoir about fighting in the Battle of the Bulge as he campaigned for his first term as alderman in 1947.

Ald. Merriam was the kind of guy who’d chase down a thief, which is exactly what happened one day in 1953. As Merriam was dictating a letter to his secretary in the rear room of his storefront ward office at 1463 E. 55th St., a man sauntered in the front door and left after the secretary called out, “May I help you?” She quickly checked and saw her purse had been opened, and $25 taken—almost $300 in 2023 money. Merriam jumped in his car and chased the thief down Harper, then hopped out of the car to continue on foot after the man jumped a fence at 56th St. Merriam followed, but the thief got away. Merriam came back later to help police search the area, from backyards to garages and basements.

Merriam was the most perfectly conceived Hollywood version of an anti-Machine candidate, running against the literal head of Chicago’s Machine. Merriam was good-looking and young, Daley was paunchy and middle-aged. Merriam was an orator, Daley had to take lessons from a Northwestern speech therapist for his Bridgeport accent—but no amount of therapy could stop his lips from turning “th” into “d,” or cure his fluent malapropisms.

In a classic movie, Merriam would have been played by Gary Cooper. The secretary would be Jean Arthur, and they’d get married. He’d run for mayor against the heavyset big city political machine boss, a fun role for Edward G. Robinson. Merriam would almost lose after some Machine dirty tricks, but then win in the end after a big dramatic speech.

In reality, you know Merriam will not win the 1955 election as our story unwinds. But he will come rather close.

Besides acting as one of the few good-government aldermen in City Council in what was called the “economy bloc,” Ald. Merriam gained particular civic prominence because he served on, then chaired, a special City Council “emergency crime committee” investigating political and police corruption in Chicago.

In 1954, WGN even ran a nine-part series starring Ald. Merriam. For “Spotlight on Chicago,” Merriam appeared “in the role of crusader for civic decency,” as the Tribune put it, “exposing political corruption.”

“A few weeks ago his name would have been only vaguely recognized by most Chicagoans,” wrote the Tribune TV critic, but Merriam had become “a TV figure possibly recognized by a million or more viewers….Today he has become a vital figure in public life.”

How convenient, with the mayor’s race coming up! I don’t mention any specific crimes uncovered because, as far as I could see, Merriam’s show didn’t result in any actual convictions. Neither, really, did the Council’s crime committee. I don’t get it either. Perhaps, as Tommy Henry of the Chicago History Podcast likes to say, “because Chicago.”

Merriam was a Democrat turned Republican for the mayoral race, theoretically capable of going beyond the city’s tiny Republican voter base to attract independents and disaffected Democrats as a “fusion” candidate. By rights, Merriam should have inherited Kennelly and Adamowski voters from the primary—but he couldn’t get Kennelly or Adamowski to endorse him. He had turned Republican, and that was a bridge too far.

Daley also had an advantage as a true regular neighborhood guy. He had union backing. He could campaign at the Stockyards by climbing on a horse and claiming he used to be a cowboy there. Meanwhile, Merriam later complained, according to “American Pharaoh,” “You know what party workers say? They say to each other, ‘Have you ever seen this Merriam take a drink? Does he ever drink? I mean, have you ever actually seen him take a drink?’”

If you’ve read this far, I know you like Mike Royko. Catch up with Mike in 1972 here, and get the political and pop culture context to his columns, so you’ll get all the inside jokes.

The Independent Voters of Illinois (IVI) gave Merriam the nod. The Tribune, Sun-Times, and Daily News all endorsed Merriam. The Tribune did so reluctantly, since Merriam was a fake Republican, but still. The Herald-American (predecessor of Chicago’s American/Chicago American and finally Chicago Today) and the Daily Defender backed Daley.

“The American decided that Daley was a man of vision and potential greatness,” wrote Royko in “Boss.” “It was also rumored that Daley had promised the editor that his precinct captains would push subscriptions for the paper, which at the time had the lowest circulation in the city.”

Merriam got plenty of campaign press by railing against Machine voter fraud. He got even more press when Daley had to drop his running mate for city clerk, Ald. Bernard Becker. The Chicago Bar Association charged that Becker was representing zoning clients on cases that he voted on in City Council.

But the vote fraud charges didn’t stick, and Daley actually profited by bouncing Ald. Becker, then shifting his candidate for treasurer into the clerk slot so he could bring in popular Chicago department store owner Morris B. Sachs for treasurer instead.

Sachs had been Kennelly’s treasurer running mate in the primary. He was even more well known than Merriam, due to his long-running local weekly Morris B. Sachs Amateur Hour radio show, which started in 1934 and shifted to television in 1949. See Mike Royko 50+ Years Ago Today here for a deeper dive into Morris B. Sachs, because Slats Grobnik once performed on the Amateur Hour.

But I mean, popular? Sachs had to move his Amateur Hour to the Merchandise Mart, and later the Civic Opera House, to accommodate the crowds.

As the campaign wore on, Daley tried to ignore Merriam’s attacks, while his Machine launched attacks of its own.

“Merriam had been divorced from his college sweetheart, the marriage a wartime casualty,” writes Royko in “Boss.” “The Machine’s agents sent out unsigned letters saying nobody knew how many children he had abandoned without support. Copies of his divorce papers were circulated in Catholic neighborhoods….Then a rumor was spread in white neighborhoods that Merriam’s second wife, who was born in France, was part Negro…Letters from a nonexistent ‘American Negro Civic Association’ were sent into outlying residential areas, urging a vote for Merriam because he would see to it that Negroes found homes and building sites in all parts of the city.”

In late March, less than two weeks before the election, Daley got to slather himself with Adlai Stevenson again at a Palmer House rally for the Volunteers for Daley.

Daley endorsed Stevenson for a second presidential run, and Stevenson really laid it on thick backing Daley for mayor. Stevenson got a standing ovation when he started and when he finished: “He charged that the Republican ‘right wing, cynically masked by the heroic picture of gallant St. George, is shown spearing an evil Democratic dragon,’” per the Trib.

Stevenson also said he wanted to pay his regards to Robert Merriam, calling him “my esteemed friend”. I could not tell from the paper accounts if that was sincere, or classic political trash talk. But it was probably trash talk.

Then, “Fred Hoehler, former director of public welfare under Gov. Stevenson, told the crowd: ‘If there’s a machine, Daley will be the engineer and he’ll run it.’”

Daley got in some great digs at Merriam at the Palmer House that night too, continuing one of his main campaign themes:

“The Republican candidate is in the impossible position of trying to walk a rope, with both ends dangling the air,” he declared. “He is trying to convince Republicans that he isn’t a Democrat, and trying to convince Democrats that he isn’t a Republican….The Republican candidate seeks to portray me as a man who would unleash all the forces of evil on the people Chicago.”

On the last big campaign day, the Sunday before the election, Daley made two television appearances. The Daily News said the “stocky, earnest candidate….repeated his contention that ‘good politics is good government, and good government is good politics.’ Daley attacked his Republican opponent…for ‘telling us that Chicago is an evil city and thereby telling us that we are evil.’”

Adlai Stevenson popped up on Daley’s TV spot “via a film record,” per the Daily News. I guess that means a pre-recorded film clip.

The Machine pulled it out for Daley on April 5, thanks again to its most loyal wards, especially Dawson’s Black “submachine” wards. But Daley’s first win was a modest one—708,222 to 589,555, a mere 55% victory. Merriam took 19 wards. Observers thought Merriam could have won with a higher voter turnout.

“The misgivings we felt over the possibility of Daley’s election were sincere,” wrote the Daily News editorial board. “We shall be glad if Dick Daley proves they were mistaken.”

“We congratulate Richard J. Daley upon his election as mayor,” wrote the Trib, adding that it hoped “he will do nothing in the coming four years to sully his good name.” And: “We start with the gravest doubts about many of the new mayor’s political associates but with much confidence in Mr. Daley himself.” Besides guys like Paddy Bauler, the Trib was talking about the mob-connected Machine politicos from the 1st Ward.

Again, note the editorials playing it both ways—they didn’t want Daley, they hoped he wouldn’t screw up, but what they were really worried about was his “associates.”

What about Robert Merriam? It’s like Frank Capra wrote his concession speech.

“In acknowledging defeat…Merriam appeared almost jubilant,” wrote the Tribune. “Believe me, as far as I’m concerned, the campaign was well worth it,” he told his cheering supporters in his jammed offices at 105 W. Monroe. “There’s always another day. We will awake tomorrow, after a good night’s sleep, refreshed and ready to carry on our efforts for a better city. Whenever we can cooperate with Mr. Daley to that end, I know you will all help.”

Maybe I should have cast him as Jimmy Stewart.

The papers had speculated that Richard J. Daley would resign the chairmanship of the Cook County Democratic Organization before running for mayor. Then they speculated he’d resign if he won the mayor’s office. During the campaign, Daley even claimed he would resign as chairman if he won.

Nope.

Next: They Were Expendable

A dip into Mayor Daley’s second and fourth blow-out elections, with the spotlight on his third campaign in 1963 against archenemy Ben Adamowski. I would not want Ben Adamowski for an enemy.

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.