If you’re not a regular reader of this site, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” is a hybrid novel/Chicago 1972 primer, posting one chapter per month. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972. Each chapter comes with fun Notes on key topics that pop up as our story progresses. This is an Optional History Chapter on the Wrigley Building, which makes its first appearance in Chapter 2. See “Part 1: William Wrigley Jr. Conquers the World” here. The final installment, “Part 3: When Chicago Wasn’t Chicago,” is here. To find out what the novel is all about, see here.

The Wrigley Building

William Wrigley Jr. hit his stride in the late teens of the 20th century. He was everywhere, donating and raising money for the Red Cross in World War I; serving on a committee to raise money to vaccinate Chicagoans against the deadly 1919 Spanish flu; commissioner of the Lincoln Park board, just to a name a few civic past times. He founded and owned the largest manufacturer and distributor of gum on Earth. He owned the Chicago Cubs, who won the National League pennant in 1918. By 1919, Wrigley owned Catalina Island and was turning it into a resort as well as spring training headquarters for his baseball team.

But to any lover of architecture, or Chicago, that was all just a warm up for the Wrigley Building.

“Fifty concrete pillars, resting on bed rock a hundred feet below the surface of what is now Chicago level, support the Wrigley building. The building superintendent is said to have laid a layer of the finest spearmint chewing gum between these pillars and either that far away bed rock or the structure itself, so that its owners can truthfully say that it rests on the foundations of the fortune which built it. What strange aspects sentiment takes at times!” –Chicago Tribune, February 30, 1921

Some drunk reporter probably made that up. Still, I hope the Wrigley Building really does have some Spearmint gum stuck to the bottom of its concrete pillars, a hundred feet underground.

Chicagoans instantly fell in love with the Wrigley Building.

Not because it broke any big records. The Wrigley Building was only 3 ½ feet taller than the city’s then-tallest building when it went up—the Montgomery Ward Tower at Michigan Avenue and Madison, named for another Chicago business mogul known for his civic pride. The Wrigley Building clock tower, at 398 feet, was quickly and easily surpassed by the 568-foot Chicago Temple in less than two years.

No; from the beginning, Chicagoans loved the Wrigley Building in a pure, chaste, old-fashioned way—just because it is beautiful.

Accounts trace Architect Charles Beersman’s inspiration for the Wrigley Building to both a tower of Spain’s Seville Cathedral, and to the neoclassical buildings of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park, where young William Wrigley Jr. hawked his brand-new Juicy Fruit gum.

The Columbian Exposition’s buildings were designed by the biggest architects of the day under the leadership of Chicago’s uber-architect, Daniel “Make no little plans” Burnham. The Columbian Exposition gained the nickname “White City” because the buildings were all covered with a cheap sort of white plaster called “staff.” It was a quick, affordable way to give the appearance of stone and marble on buildings that looked monumental, but were actually more temporary than a teepee. A teepee is sturdy—regularly dismantled, folded up and reconstructed in a new location—while all but one of the 14 gigantic exposition halls from the White City vanished within a year after the fair closed. Some burned to the ground by accidental fires, the rest were demolished. So too went nearly all the hundreds of smaller buildings.

A century later, the only building left in Jackson Park for Steve to see was the Palace of Fine Arts, transformed into the Museum of Science of Industry. The Fine Arts Palace survived because it was the only one built with a solid brick infrastructure, plus an iron roof and floors to make it fireproof for the priceless artwork inside. Even then, it took Sears Roebuck president and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald—yet another Chicago mogul with civic pride--to save the Fine Arts Palace. Rosenwald donated $3 million to create the Museum of Science and Industry. The cheap plastery staff covering the Arts Palace was replaced with real limestone.

From some angles and distance, the Wrigley Building looks like a single coherent structure. From others, the building appears to have a deep perpendicular divot slicing through, just north of the clock tower. That’s because the Wrigley Building is two structures—the original south building with its clock tower, and the larger northern “annex” which opened several years later, at that time across North Water Street.

In 1957, the Wrigley company decked over North Water Street between the two towers—from Michigan Avenue to Rush Street—and built the landscaped plaza in between. (The original plaza was designed by L.R. Solomon, J.D. Cordwell & Associates.)

The Wrigley Building is covered with approximately 250,000 shiny white terra cotta tiles. “I always heard the story of how they washed the building regularly like a dinner plate,” recalls Chicago’s official cultural historian (now emeritus), Timothy Samuelson. “Sometimes when driving by with my family, we’d see men on scaffolds scrubbing away.”

They had to scrub the Wrigley Building, especially in the early days when Chicagoans burned coal to stay warm. The Tribune ran a huge picture of the south tower just before it opened in 1921, pointing out the difference between the white half of the building that had just gotten washed, and the dark half waiting for a bath. The Tribune called the stark difference “an eloquent lesson” in the smoke that “rolls out of thousands of chimneys and spreads in gray curtain between the city and the blue spring sky.”

Cladding the Wrigley Building in white terra cotta was like putting on a white dress to go mud wrestle all day. You have to admire the optimism.

Architect Beersman ordered six different shades of white tiles for the Wrigley Building, growing progressively lighter toward the top. “The idea was that it would look like the sun was always shining on the building’s upper stories,” Tim Samuelson explains. “In later years, I fished damaged pieces of the terra cotta from the dumpster behind the building when repairs were being made. When pieces removed from the top were placed next to pieces from the bottom, you definitely could see the difference.”

And yes, Chicago’s official Cultural Historian really goes dumpster diving for pieces of the Wrigley Building. You should see some of the other stuff he’s dug out of actual garbage dumps and buildings under demolition.

Like the Columbian Exposition’s White City, the Wrigley Building is beautiful by day, enchanting by night. Since 1921, the entire Wrigley Building has been lit like a giant Christmas tree by varying forms of flood lights from dusk to dawn, not counting World War II and the 1973-74 energy crisis.

At night, the White City dazzled late 19th century crowds with thousands of newly invented electric lights and streetlamps illuminating the massive buildings and fair grounds. It must have been like a nonstop fireworks show for the wondering fair goers, used to homes and city streets dimly lit by gas lamps. Those 19th century people had literally never seen anything like the Columbian Exposition lighting. The Wrigley Building still produces that level of awe in 21st century people, who still stare at it by night from the Michigan Avenue Bridge, now named the Du Sable Bridge--even though these people now live in a world so used to computerized special effects that real life is seldom any match for movies, TV or video games.

I can’t truly convey to you the difference between looking at a picture of the Wrigley Building, and what it feels like to stand on the bridge at night and take in its glowing presence. The best photographers can’t capture it either. This is no fault of mine, or the photographers. You have to be there to feel the soul of the building.

Location, Location, Location

The Wrigley Building’s beauty would not shine as brightly, or burn so deeply in Chicago hearts, if it were hidden away near, say, the old Stock Yards. The genius of the Wrigley Building lies as much in its location as its design or lighting, both then and now. But surprisingly, this inspired location was not initially the garden spot of this urbs in horto, city in a garden—Chicago’s official motto.

Walking north up Michigan Avenue toward the Chicago River, the Wrigley Building looks like it’s standing on the bridge, waiting for you. That’s because on the north bank, smack where the Wrigley Building stands, Michigan Avenue suddenly jogs east to connect with what used to be Pine Street.

Until 1920, there was no Michigan Avenue north of the river, and no bridge. Both sides of the riverbank were lined with factories and warehouses. Michigan Avenue ended at the south river bank, and on the north bank, a bit further east, narrow Pine Street was residential. Prominent Chicagoans planned and plotted for nearly twenty years to build the Michigan Avenue Bridge and transform the north side of the river into an upscale extension of downtown. The Michigan Avenue Bridge was a major feature of Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago. But big dreams require big money and land acquisition, and both take time. Bridge construction finally started in spring 1918, just as William Wrigley Jr. went shopping for the site of a grand world headquarters for his company, which, let’s say it one more time, was the largest manufacturer of gum on Earth.

There’s the Wrigley Building, waiting for you on the north side of the bridge like an old friend on a crisp fall day. Maybe you’re meeting each other for lunch to catch up.

And here’s the Wrigley Building waiting for you on a chilly night just before Christmas. Maybe you’re going to walk over to Marshall Field’s on State Street and look at the Christmas windows. Admittedly Marshall Field’s is, as I write, now Macy’s. But at least it’s still there.

In 1919, as the Michigan Avenue Bridge construction continued, William Wrigley Jr. bought the best construction site in the city for $217,920—about $3.5 million in 2021 dollars. When the Wrigley Building opened for tenants in 1921, the gleaming windows in its shining white terra cotta walls looked out over brand new north Michigan Avenue.

Unfortunately, the front windows also looked at the sprawling old Kirk soap factory right across the street. The back windows looked at a warehouse serving as offices, research laboratory and small factory for another global corporate giant born in Chicago: the Kraft Cheese Company. More on Kraft in the Trump Tower section of Chapter Two Notes.

As you can see below, early hand-colored linen postcards viewed the Wrigley Building from the south bank of the river, pointing the camera northwest. That angle stops the frame just before the poor ignored Kirk soap factory, to the right (east).

Notice how the day-time scene pulls back a little further to angle the shot so that the southeast corner of the brand new Michigan Avenue Bridge obscures the area behind the Wrigley Building, to its west. You can just barely see that area in the night-time postcard—there’s a squat red building with a black water tank on top. That’s Kraft.

Soap to the right of them, cheese to the left of them.

James S. Kirk founded his soap company only two years after Chicago became a city in 1837. Kirk manufactured national brands like American Family Soap and Jap Rose Soap, soon household names—more on that in a bit. Before the 19th century ended, Kirk was already one of the city’s biggest employers with 600 workers. Kirk’s first factory sat on the river’s south bank, on the former site of Fort Dearborn. Kirk moved to the north bank in 1867—just in time to go up in flames during the 1871 Chicago Fire. Kirk bravely rebuilt, and the Kirks became a leading city family. James S. Kirk’s son, Milton, served as a director of the Columbian Exposition. Then came the Michigan Avenue Bridge project.

After the Kirks had spent 80 years creating jobs and paying taxes in Chicago, the city was outraged when Kirk refused an offer for the southwestern portion of its property. Kirk insisted it wasn’t standing in the way of the “boulevard link,” as the Michigan Avenue Bridge project was called. But the Kirks wanted more money—and more time to finish building a replacement plant on the west bank of the Chicago River’s North Branch at North Avenue.

The impatient Chicago Tribune ran a front page editorial cartoon on October 18, 1917 showing one way to build around Kirk—by John T. McCutcheon, who would become known as the “Dean of American Cartoonists.”

Eventually, the city condemned enough Kirk land to bulldoze through and build the bridge. The soap factory continued operating on the rest of its land. You can’t blame Kirk for following the more accurate Chicago motto coined by future Chicago newspaper columnist Mike Royko: “Ubi est mea?”, or “Where’s mine?” After all, in true Chicago fashion, the whole Michigan Avenue Bridge project had tripled in cost by the time Kirk’s land was condemned. As the Tribune itself said of the city’s excuses for the cost overruns, “who can swallow it?”

The Tribune had its own reasons to wish Kirk away. The paper was about to build its elegant new headquarters, Tribune Tower, on Michigan Avenue just north of the Kirk soap factory.

Remember that space between the Wrigley Building’s two towers? According to the building’s official website, that space was originally covered with a “glass screen” to blot out the existence of the Kirk soap factory, as well as the Kraft factory to the west. Presumably the glass screen didn’t cover the entire distance from the ground to the top floor.

“For Tribune Tower tenants who sniff long and bitterly when the wind is from the south,” wrote the Tribune in 1928, “for Wrigley building dwellers who do likewise when the breeze is from the lake and for the occupants of ‘333’ and the London Guaranty building who wrinkle their noses with annoyance when the wind hails from the north side, here’s a word of cheer: the old Kirk soap factory overlooking the Michigan Avenue Bridge plaza probably will shut down on or before next January.”

Would you want a soap factory across the street? If so, you aren’t familiar with how they made soap in the 1920s.

But no one remembers that Chicago had the Kirk soap factory to thank for the first lighting of the Wrigley Building. The Tribune ran a picture on July 27, 1921. “The Wrigley Building at night—it looks like a snow palace, a tower of frost,” the Tribune marveled. “The effect is produced by 129 X-ray floodlights, strung on the roof of the Kirk soap factory opposite.”

(X-rays did exist at this time. Chicagoan Clarence Darrow, probably the most famous lawyer of the 20th century, ordered notorious clients Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb X-rayed top to bottom in 1924 as they awaited trial in the old Cook County jail. Darrow hoped for a physical reason to explain Leopold and Loeb’s cold-blooded murder of young Bobby Franks. However, the term “X-ray” to describe the Wrigley Building’s floodlights was, hopefully, metaphorical.)

Here’s a 1920s photo of the north side of the Kirk soap factory, probably shot from Tribune Tower, looking southwest. The spanking new Wrigley Building is a sliver on the far right. I was astounded to finally find any picture of Kirk Soap—and of course, it was on the most incredible private internet treasure trove of Chicago pictures I know, John Chuckman’s Photos On Wordpress.

You’re wondering about that sign for “Jap Rose Soap.” Yes, that’s short for “Japanese.” If 1972 isn’t a safe year for the timid, as I warned in Chapter One, the 1920s were downright dangerous. The term “Jap” wasn’t considered offensive by Americans back then. In fact, in the late 19th century/early 20th century, Americans believed the Japanese bathed daily, which was substantially more often than the average American of that time period. So the Kirk soap company named its fanciest soap “Jap Rose Soap” to signify it excellence. Americans starting calling the Japanese “dirty Japs” only after Japan bombed American naval ships at Pearl Harbor in a surprise attack in 1941, thus beginning the Pacific portion of World War II. During World War II, Americans were encouraged to de-humanize their opponents, and they did so with gusto. But before World War II, Chicagoans considered the Japanese people the epitome of cleanliness, and they happily ate Mrs. Japp’s Potato Chips. After Pearl Harbor, Mrs. Japp’s Potato Chips became Jays Potato Chips. Although I wasn’t able to sniff this out, I strongly suspect this is when Jap Rose Soap also disappeared from American store shelves.

Soon after Kirk Soap Company moved to its new digs on North Avenue in 1929, Procter & Gamble gobbled up the company. You’ve probably heard of them. The P&G plant still employed 600 people in 1980, but shut down in 1989 after “a thorough economic analysis” concluded P&G should throw Chicago under the bus. The factory site soon turned into a 137,000 square foot Home Depot.

Then in 2005, the Wrigley company closed its historic gum factory at 35th and Ashland and moved all its jobs out to suburban Yorkville. At the same time, the profitable Wrigley Company moved its headquarters out of the Wrigley Building and into its fancy schmancy $45 million “Global Innovation Center” on booming Goose Island, built with $15 million in TIF funds earmarked for blighted areas.

And that’s how the Wrigley company ended up, 76 years later, right across the street again from its old nemesis the Kirk soap factory, albeit its former site.

Many grand plans for the Kirk soap factory site came and went in the decades afterward, including a restaurant and nightclub designed by Daniel H. Burnham Jr., son of Chicago uber-architect Daniel Burnham. All were for nought. At first the vacant lot served as a baseball field for office workers on their lunch hours. By 1932, the land was paved to create the second largest parking lot in the city.

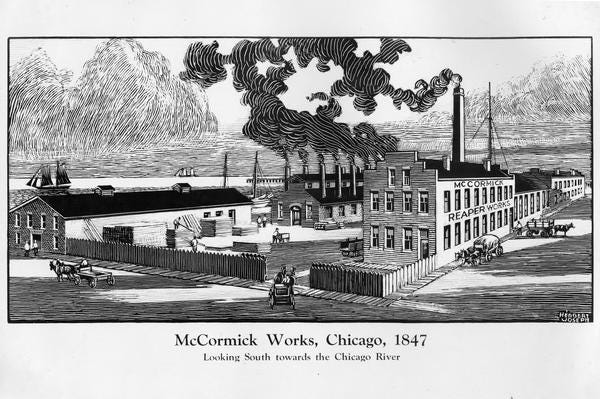

Then in 1963, the 35-story Equitable Building began sprouting on the eastern end of the land. The vast area in front of the Equitable Building, lining Michigan Avenue, would become Pioneer Plaza. Mayor Richard J. Daley and other officials posed with a shovel for the ground breaking. Before Kirk soap, this particular slice of the site had hosted the first McCormick Reaper Works, which later merged with several other farm equipment companies to create International Harvester. International Harvester grew so exponentially, it opened its own steel mill on the South Side, confusingly named “Wisconsin Steel.” Fittingly, International Harvester leased 11 floors of the Equitable Building —the largest office rental lease ever in Chicago at that time.

Pioneer Plaza originally included a 48-foot diameter pool with small fountain jets in the center. Not much to look at, but the flat raised edge was like a big round park bench, very nice to sit on in the summer and look at the Wrigley Building. I rather miss it. The names of 25 early Chicago “pioneers” were set in bronze on the fountain’s outer rim.

The 25 Chicago “pioneers” honored on the Pioneer Court fountain included among others: Architect Daniel Burnham, author of the Plan of Chicago and chief overseer of the Columbian Exposition; Sears Roebuck president and philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, who saved the building that became the Museum of Science and Industry and took no credit for it in the name; William Rainey Harper, first president of the University of Chicago; Montgomery Ward, founder of an eponymous mail order catalogue business and later department store, as well as the driving force behind saving Chicago’s lakefront as public land; John Whistler, first commander of Fort Dearborn; Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable, usually described as a Haitian trader, who settled on that very spot by about 1770 and thus is most deserving of the title “first citizen” if you forget about the existence of Native Americans; and John Kinzie, who bought Du Sable’s land in 1803 and would intermittently long and undeservedly bear the title of Chicago’s “first citizen”—at least as late as the day in 1965 when the Tribune wrote about Pioneer Court’s new fountain. Again, it was 1965, so it is also not surprising that the fountain acknowledged only one woman as being present at the creation of this vast metropolis--Jane Addams, tireless social pioneer and founder of Hull House.

The Pioneer Plaza fountain disappeared in a 1992 redesign of the plaza. Since then I feel like they tear up the whole thing and repave it just slightly differently every other year. In 2017, global computer giant Apple opened a glamorous glass showcase store with a flat, shiny metal roof on the riverbank portion of Pioneer Court.

In the 2017 picture below, the uninspiring Equitable Building marks off Pioneer Plaza’s eastern end. As is often the case, you can just barely make out the wafer-thin metal roof of the riverside Apple store that seems to hover in mid-air above the plaza at about the level of the Equitable Building’s first row of windows.

Imagine trying to describe or explain the Apple store to Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable, 19th century soap tycoon James S. Kirk, or William Wrigley Jr.

Wrigley Building: Architect Charles Beersman of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, a successor to Daniel Burnham’s firm; south tower with clock completed April 1921, north tower completed May 1924; 400 and 410 N. Michigan Avenue. DuSable Bridge, originally Michigan Avenue Bridge: Architect Edward H. Bennett with Thomas G. Pihlfeldt, city bridge engineer and Hugh Young, engineer of bridge design, 1920.

Next, Part 3: The Wrigley Building before Chicago was Chicago

SUBSCRIBE

If you’re not immediately repelled, why not subscribe? You’ll receive a new chapter of “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” every month in your email box, along with a weekly compilation of the daily items on social media: THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, and MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY.

And why not SHARE?

Maybe you know someone else who would enjoy reading about a ten-year-old Italian-American kid on the South Side of Chicago in 1972. Didn’t your parents teach you to share?