The Wrigley Building Part 1: William Wrigley Jr. Conquers the World

OPTIONAL HISTORY CHAPTER

If you’re not a regular reader of this site, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” is a serialized novel/Chicago 1972 primer. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972. Each chapter comes with fun Notes on key topics that pop up as our story progresses. This is an Optional History Chapter of the Wrigley Building, which makes its first appearance in Chapter 2. See “Part 2: The Wrigley Building” here. The final installment, “Part Three: Before Chicago was Chicago,” is here. To find out what the novel is all about, see here.

The short version: William Wrigley Jr. came to Chicago in 1891 and created the biggest gum company in the 20th century world, churning out Wrigley’s Spearmint, Double Mint (later “Doublemint”) and Juicy Fruit. Wrigley made a pile of money, bought the Chicago Cubs baseball team and renamed their park Wrigley Field. Finally, he built the Wrigley Building as his company headquarters.

By day, the Wrigley Building is a bright, beautiful butterfly of a building hovering over the urban prairie; by night, a glowing, luminous moth perpetually drawn to the blazing floodlights trained on it.

Architect Charles Beersman ordered six shades of white terra cotta tiles to cover the Wrigley Building, growing progressively lighter toward the top. “The idea was that it would look like the sun was always shining on the building’s upper stories,” emeritus City of Chicago Cultural Historian Tim Samuelson explains. “In later years, I fished damaged pieces of the terra cotta from the dumpster behind the building when repairs were being made. When pieces removed from the top were placed next to pieces from the bottom, you definitely could see the difference.”

And yes, Chicago’s official Cultural Historian really goes dumpster diving for pieces of the Wrigley Building. You should see some of the other stuff he’s dug out of actual garbage dumps and buildings under demolition.

The best place to view the Wrigley Building is from the Du Sable Bridge, due east. The bridge opened in 1920 as the Michigan Avenue Bridge and was rechristened 90 years later in 2010 for Jean Baptiste Pointe Du Sable, the first permanent resident in what would become Chicago. Since our story is happening in 2003, it’s still the Michigan Avenue Bridge in this book.

Remember how the morning sun had to cross the Michigan Avenue Bridge, at the start of this chapter, to reach the Wrigley Building? It’s an apt image, because without this bridge, there wouldn’t be a Wrigley Building as we know it.

Now let’s dive deeper.

William Wrigley Jr. and his company

Thanks to William Wrigley Jr., you instinctively associate the word “spearmint” with a clean, blazing white, although the spearmint plant is green.

You hear “Doublemint,” which is not a word at all but an invention of the Wrigley Company, and now your mind imagines a refreshing expanse of green.

“Juicy Fruit” conjures a deep, sweet yellow, even though the only fruits you instantly identify with “yellow” are bananas, which are not juicy; and lemons, which are not sweet.

Such is the power of advertising. So much so, no one even remembers that Juicy Fruit spent its first decades in a green wrapper, just like Double Mint but with stripes. Someone at the Wrigley company finally figured out it didn’t make sense to use the same color for two different major products.

The legend of William Wrigley Jr., born in Philadelphia in 1861, has him selling wares from his father’s soap factory on Philly streets “as a little boy,” per the Wrigley Company’s official website. Other retellings put Wrigley’s peddling as early as age 11. In 1891, the company website says Wrigley traveled west to Chicago with “just $32 in his pocket and a dream of running his own business.” That would be his own soap business.

That number—$32--makes it into nearly every version of the Wrigley legend.

But if William Wrigley’s father owned even a small soap factory, and Junior came to Chicago to sell his father’s product in a hot new market, is it likely that he arrived almost penniless? No. For one thing, $32 went a long way in 1891. And if you read the official Wrigley Company website closely enough, another page includes a picture of William Wrigley. A small caption underneath says Wrigley came to Chicago with $32 -- “and a check from his uncle for $5,000 to start a new business.” William Wrigley Jr.’s uncle’s check would be $150,700 in 2021 dollars.

That number--$5,000 ($133,250 in 2021)—is rarely mentioned.

However, we’ll let this slide. You had to get very rich indeed in the 19th century before life was easy. Salesmen like Wrigley visited customers in horse-drawn carts. We know Wrigley wasn’t secretly driving a luxury car on his rounds, because like so many things, mass-produced cars were some years off. You couldn’t even buy a package of pre-sliced cheese in a store back then. Rich uncle or not, William Wrigley surely worked hard and exhibited a genius for sales: He was smart enough to dump his dad’s soap when the free baking powder he handed out to promote the soap took off. And then Wrigley proved himself a veritable Einstein: He dumped the baking powder when the free promotional gum he was handing out to promote the baking powder took off.

Wrigley contracted with the Zeno Manufacturing Company to produce his own gum. Juicy Fruit was created in time to hawk at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago’s Jackson Park, a stone’s throw from Steve Bertolucci’s home as a grown-up one hundred years later, in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood. (For readers who came for the architecture, this is part of “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Click here if you’d like to know more.)

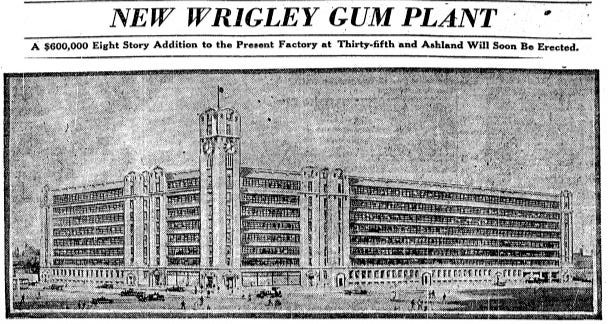

Fast forward to 1911. Wrigley’s Spearmint is literally the biggest gum in the entire world. William Wrigley absorbs Zeno to form the Wrigley Company and goes on to build a massive gum factory in Chicago’s Central Manufacturing District--which is not centrally located but on the South Side. The Wrigley factory stood at 35th and Ashland, a bit west of the White Sox’s Comiskey Park.

Here’s the Tribune touting plans for a 1919 expansion of the original plant:

By that time, Americans nationwide were bombarded with Wrigley advertising in newspapers, on streetcars, on billboards. Everyone knew “The Flavor Lasts.”

And that was around the world. Here’s Wrigley advertising seen on a postcard of Piccadilly Circus, circa 1930-40, the London equivalent of Times Square.

As the United States headed into World War I, William Wrigley Jr. was just hitting his stride. Wrigley’s canny advertising encouraged consumers to buy Wrigley’s and “send it to your friend at the front”. The Doublemint Twins would be born in 1939. Here’s a 1935 Wrigley sales brochure to feast your eyes upon.

Lovable Losers

Next William Wrigley Jr. embarked on another project that would bear his name. In 1916, he and a group of wealthy Chicagoans bought stock in the Chicago Cubs. After buying a second block of stock later that year, he told reporters his personal interest was up to $165,000:

“I wish I had more,” he said. “I think the Chicago Cubs ought to be owned by Chicago men and I’m glad to be interested. It wouldn’t make any difference to me whether they made money or not. The Cubs form a Chicago institution and there is a sort of civic pride in being interested.”

Civic pride! William Wrigley Jr. put that pride into action by 1918, buying up controlling interest in the team. In 1926, the Cubs ball park was renamed Wrigley Field. But as the saying goes, pride comes before the fall. The Cubs had played in three consecutive World Series—1906, 1907 and 1908—winning the last two. But it wouldn’t happen again for 108 years.

As the Wrigley years went on with nary a World Series in sight, Cub fans wished the Wrigley family would take a more businesslike approach to the Cubs. When William Wrigley Jr.’s grandson sold the team to the Tribune Company in 1981, Chicago Tribune sports columnist Bob Verdi declared the Wrigley family “had operated the Cubs as a civic concern rather than a going concern for years” and that William Wrigley III had “finally conceived his finest civic gesture yet. He sold the team.”

Ah, but there’s more irony to the Cub sale. Patriarch William Wrigley Jr. took out a $1 million life insurance policy on himself in 1919, to make sure his businesses would stay in the family. At age 58, Wrigley started paying a yearly $60,000 premium. “I am following the policy of many men who see largely increased federal and state inheritance taxes,” said Wrigley. “A million or a million and a half to pay taxes and to throw into the business in ready money after the death of its head would be a great help to any estate.” And it was: William Wrigley Jr. successfully passed along his company and the Cubs to his son, Phillip “P.K.” Wrigley. But in 1981, grandson William Wrigley III was forced to sell the Cubs to pay $40 million in estate taxes after P.K. and his wife died within months of each other.

After another ownership change, the Cubs finally won the World Series again in 2016.

Great-grandson William Wrigley Jr. took over as president and CEO in time for the 21st century. I agree, his name is confusing—sometimes he is referred to as William Wrigley IV, or William Wrigley Jr. II, but newspapers of the time referred to him as William Wrigley Jr. Wrigley Spearmint gum was no longer the biggest on earth, but the Wrigley Company still supplied almost half of the entire planet’s gum consumption. In 2002, the Wrigley company announced it wanted to build a grand “Innovation Center” on Goose Island, a piece of North Side land then so popular that the proposed site was the last big parcel left.

The Tribune reported the project depended on tax increment financing (TIF) subsidies from the city—a form of city charity that was supposed to be spent on blighted areas with no other hope of development. The Tribune noted that the Wrigley company, “with second-quarter sales of $708.5 million, would not seem to need a city subsidy,” but “the company is expected to argue that a location outside the city would be more economical.” In other words, in the immortal words of Paulie in “Goodfellas” via narrator Henry Hill : “Fuck you, pay me.”

How do you think that story ends? Yes, children: The profitable Wrigley Company got $15 million in TIF funds earmarked for blighted areas, to build on booming Goose Island. In 2005, Wrigley opened its fancy schmancy $45 million “Global Innovation Center” on the North Side…and closed its historic South Side plant at 35th and Ashland. Wrigley sent the South Side jobs to west suburban Yorkville. Wrigley also found enough change in its pockets that year to buy Life Savers and Altoids from corporate giant Kraft Foods, Inc.--for $1.46 billion.

But today, the William Wrigley, Jr. Company is merely a cog in the works of behemoth candy corporation Mars Inc. Great-grandson William Wrigley Jr. sold the company in 2008 for $23 billion. Mars moved the last of Wrigley corporate operations out of the Wrigley Building and into the “Global Innovation Center” center in 2011.

Mars sold the Wrigley Building that same year to an investor group including the founders of Groupon and the company currently managing this city treasure, Zeller Realty Group. Chicago named the Wrigley Building a city landmark in 2012. The new owners gave it a thorough rehab and modernization the following year. In 2018, Chicago billionaire Joe Mansueto, founder of Morningstar, bought the Wrigley Building for $255 million and released a statement saying he was committed to preserving its legacy.

As I write, the Wrigley Building is a gleaming symbol of civic pride. The abandoned factory at 35th and Ashland, not so much. After Wrigley chucked it for Yorkville, the factory sat vacant and deteriorating for 14 years. Then, in 2020, developers knocked it down and built an Amazon “last-mile” warehouse. Now, when you order something from Amazon, you might be getting it from the old Wrigley factory site.

The Cubs still play in Wrigley Field, and the North Side neighborhood around it is called Wrigleyville. If you’ve read Chapter 2, you know Steve’s best friend at work Bill, a South Sider and White Sox fan, would not be caught dead in either place.

Next, Part 2: The Wrigley Building

SUBSCRIBE

If you’re not immediately repelled, why not subscribe? You’ll receive a new chapter of “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” every month in your email box, along with a weekly compilation of the daily items on social media: THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, and MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY.

And why not SHARE?

Maybe you know someone else who would enjoy reading about a ten-year-old Italian-American kid on the South Side of Chicago in 1972. Didn’t your parents teach you to share?

We’d love to hear from you.

The Wrigley Building will shine more brightly and now I know why after reading this fascinating retrospective! I've sent a few shares to others just now