THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972: Did Gwendolyn Brooks inspire "Sylvia"?

Literary Supplement #2

To access all website contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 is part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. Follow THIS CRAZY DAY on Twitter: @RoselandChi1972.

Surely poet Gwendolyn Brooks doesn’t need an introduction, especially to Chicago readers? Here she is, nonetheless, because the look of joy on her face in this photo is a poem in itself.

Gwendolyn Brooks was Illinois Poet Laureate, but she was intrinsically Chicago. Like Saul Bellow and Nelson Algren, the other two internationally famous Chicago writers alive and living here in 1972, Brooks was born elsewhere (Kansas City) and moved to Chicago early, growing up in Bronzeville.

Per the Poetry Foundation: “Gwendolyn Brooks is one of the most highly regarded, influential, and widely read poets of 20th-century American poetry. She was a much-honored poet, even in her lifetime, with the distinction of being the first Black author to win the Pulitzer Prize. She also was poetry consultant to the Library of Congress—the first Black woman to hold that position”.

Two of Brooks’ most well known works are named for Chicago places—her first book of poems, “A Street in Bronzeville” from 1945; and “In the Mecca” from 1968. In 1972, at 55, Brooks published the first volume of her autobiography, “Report from Part One.” A future Literary Supplement will review Brooks’ life more thoroughly via “Report from Part One” because—and I hate to admit this—I don’t own it at this writing. It’s a happy coincidence that the book was released in 1972, giving an excuse to wallow in that work alone for an entire future post.

My favorite verse from “The Mecca,” also one of my favorite verses of all time from anything:

“What else is there to say but everything?”

Most of Gwendolyn Brooks’ appearances in the 1972 papers are brief accounts of her readings around town; handing out her own Poet Laureate Awards to young Chicago poets; attendance at important events such as the ribbon-cutting for the brand-new Johnson Publishing building at 820 S. Michigan, where she also recited a poem written for the occasion, sadly not included in press accounts; and receiving honors, such as an honorary doctorate from De Paul University. We’ll sample the most interesting Brooks coverage.

Here’s Brooks in the Chicago Daily Defender during an April 1972 reading at the First Unitarian Church, 57th and Woodlawn:

Chicago Daily Defender

April 8, 1972

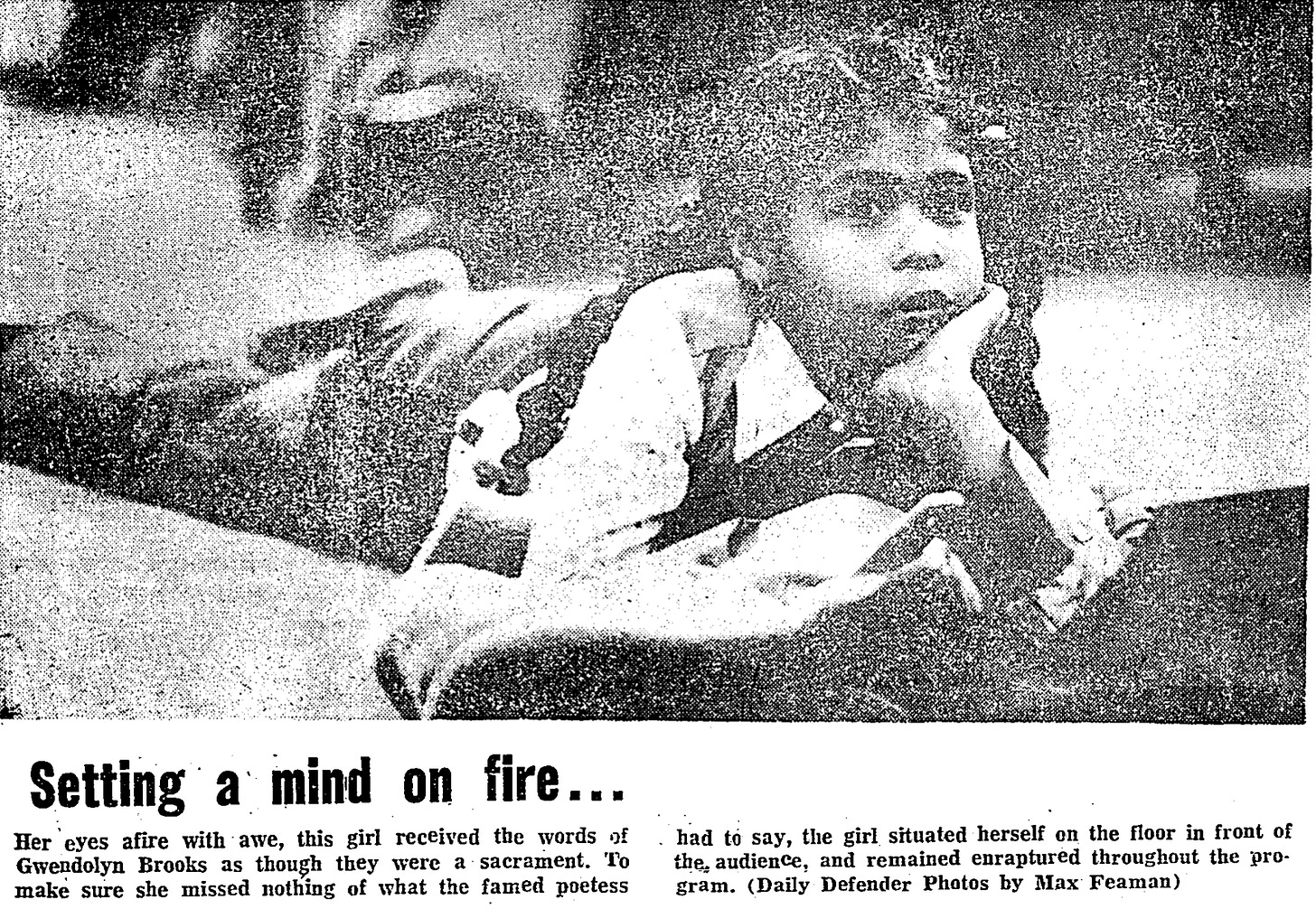

Perhaps even more captivating is this unnamed little girl, taking it all in, also from the Defender:

Brooks wrote this poem specifically for the Daily News after the death of legendary gospel singer Mahalia Jackson:

Chicago Daily News

January 29-30, 1972

Don’t miss Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today

Surprisingly, I can’t find a book review for Brooks’ autobiography in the Tribune or Defender digital archives, and I don’t recall seeing one in Chicago Today—though I haven’t thoroughly filed the December clips yet, so I may update this post. For “Report from Part One,” we just have a Charlie Cherokee Says column mention, and a Daily News review.

Chicago Daily Defender

November 15, 1972

And yes, Younger Readers, the Defender ran a social/political gossip column called “Charlie Cherokee Says,” starting in the 1940s. See this January 4 item for some background.

Chicago Daily News

December 23, 1972

Gwendolyn Brooks’ autobiography snagged the Daily News’ “Book of the Week” designation, which meant a nice long piece by Herbert Nipson, who was executive editor of Ebony magazine.

“The autobiography of a celebrated poet should be a very special thing and this one is,” writes Nipson. “There is little straight, dull ‘autobiography’ about this book. The author moves about in time and space—from childhood to now to youth and back to childhood—but every transition is smooth and right.”

Throughout the book “runs the theme of her rediscovery of blackness, starting with the opening words: ‘When I was a child, it did not occur to me, even once, that the black in which I was encased (I called it brown in those days) would be considered, one day, beautiful. Considered beautiful and called beautiful by great groups. I had always considered it beautiful. I would stick out my arm, examine it, and smile.’ It was not until she was in school that she found the hierarchy of color among her ‘colored’ classmates and learned, alas, that black was at the bottom of the ladder.”

Nipson describes Brooks’ youth in the 1940s and ‘50s on the South Side among many other Black artists, writers, musicians and dancers as a time when “liberal whites sought out talented blacks and full integration was the goal of both….Gwendolyn Brooks, first Negro ever to win a Pulitzer Prize, was the darling of the city—invited to North Side parties, sought after by publishers trying to woo her away from Harper & Row, written up by the white papers and even asked to review books written by white authors.”

Then in 1967 came the well known Fisk University Writers Conference, where Brooks appeared with writers like Lerone Bennett and Imamu Amiri Baraka, who were the “heroes” of the Black students, writes Nipson, while they only “coldly respected” Brooks.

“What was said, the excitement of the young blacks, made Miss Brooks look again upon her blackness. And, as in her childhood, she found it beautiful,” writes Nipson. “Her commitment to her blackness became a total thing. Borrowing a page from poet Don L. Lee, she stresses the importance of the new integration of ‘negroes with black people’ and that the ‘emphasis must be, not against white but for black.’”

Nipson reminds us that Brooks then switched from her major publisher, Harper & Row, and began working with small Black publishers. “She believes that if black book publishing companies are to succeed they need the best black writers. And she is dedicated enough to make that switch.”

The Tribune also ran two articles in 1972 on Brooks with lots of interesting quotes.

Chicago Tribune

September 2, 1972

by Barbara Rehm (UPI)

Barbara Rehm never mentions where she sat down to interview Gwendolyn

Brooks, so I like to imagine they were drinking coffee at Brooks’ long time home at 7428 S. Evans. Rehm describes Brooks sitting “in the half-light, hair covered by a blue bandana.”

Some choice excerpts:

Basic background:

“I grew up on the city’s South Side—43rd and Champlain. We were poor, but were not the poorest. My father was a janitor. He loved poetry and would recite to us often.

“I was quiet as a kid. Or so people thought. Inside I was raging, questioning. At 8 I had hopes of becoming a poet.

“At 16, the Depression hit. My father made $25 in a good week. There were not many good weeks then.”

Noting that she hadn’t lived with her husband since 1969, though they’re weren’t divorced:

“I never want to live with anyone again. I like being by myself. You know, free to wear a nightgown all day or your hair in tight braids. I just don’t want to have to get ready for a husband.”

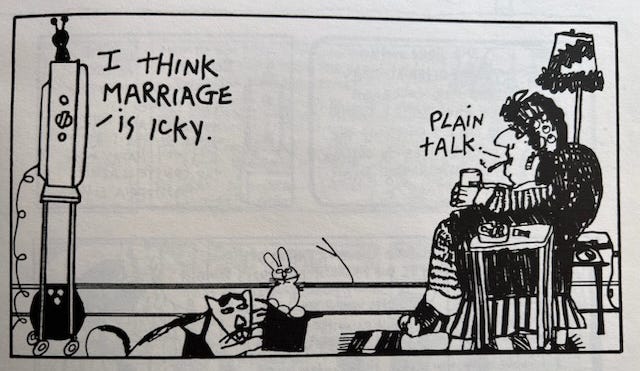

It occurs to me that Gwendolyn Brooks may gave been a partial inspiration for another creation from our lovely city: the genius comic strip “Sylvia,” by Chicagoan Nicole Hollander.

On Chicago:

“My first love is the city. Asking me why I like Chicago is like asking me why I like my blood. It’s vital. Anything can happen. I love its solitude, its isolation.

“The city is a good place for people. You’re shoved in there with more people. You have to learn about other fellows and get to know more ways of life.”

Winning the Pulitzer Prize:

“It was 5 p.m. May 1, 1950. I guess you could say I got the news in the dark. When the phone rang, the electricity was out. We couldn’t pay the bill. My feelings were so scrambled. It still seems impossible. I’m a plain, ordinary person. You wouldn’t expect anything like that to happen to me.”

Finally:

“I have no regrets with life. Things have happened to me I’m sorry for. Sure. But I’ve always spoken up for myself. And now, I’m rather old…and inarticulate.”

Chicago Tribune

November 15, 1972

by Ron Yates

Gwendolyn Brooks appeared at the Chicago Public Library’s auditorium—these days it’s the Chicago Cultural Center—and delivered a lecture to an audience of over 300, as part of a lecture series on Chicago.

Brooks wore a black scarf and brown glasses. Ron Yates describes the audience listening “in mute tribute as her words filled the room, painting vivid word pictures of their city.”

Excerpts:

“Chicago is redemptive, up-chinned, and leaning toward indelible, substantial light—uniting fever and ice in dialog and bond. I find myself celebrating the iron will, the flying smile, the hale heart of this rich rebel Chicago whose vagueness reverses in a little while.”

“I have lived in this city all my life. I discount the initial month I spent in the wilds of Topeka, Kansas. The mixtures and meshes and magics and madnesses, the miracles of the city have undeniably influenced my human condition.

“I find myself calling this a city of yeast and yield and clangor, and lunge and languor both; of maul and mercy, of repealed perils, with an even grander range and reach ahead.”

Then Brooks challenges the audience, or at least a portion she believes is present:

“Most of you probably expect me to have an interest in black people. Some two and a half or three of you might deem my stressing such an interest cruel, selfish, racist. You who deem so are probably ardent applauders of the pouring of the green in city waters on St. Patrick’s Day—applauders of green ribbons and green-ornamented parades.

“I don’t know what would happen to whatever stability of the firmament there is if blacks chose a St. Lumumba Day or a St. Nyerere Day or a St. Malcolm Day and paraded and tied black ribbon across State street, and poured black ink into the Chicago River. Yet in view of official affection for greenness—why not?”

This, Yates relates, got a few guffaws.

Conclusion:

“I tell you voyage down to 63rd Street. I tell you Lake Shore Drive is next door to the ghetto and what you leave there shall be with you still.”

Gwendolyn Brooks Field Trip

Looking for a local field trip? You can start with Gwendolyn Brooks’ longtime former home at 7428 S. Evans…

…then check out Gwendolyn Brooks Park, about a mile away at 4542 S. Greenwood. The park features a beautiful sculpture of Brooks by Margot McMahon, sponsored and funded by the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. Read more about sculpture and CLOF’s 2018 dedication at the CLHOF website here.

And thanks to Lady Topham Catt (@LadyTophamCatt) on Twitter, I learned that Gwendolyn Brooks is buried at Lincoln Cemetery in Blue Island. Her grave is well worth a visit. All photos thanks to Lady Topham Catt:

What about the legendary apartment building from Brooks’ “In the Mecca”? Here’s an 1893 ad for the then brand-new luxury residences at Dearborn at 345th, from Chicagology:

Built in time for the Columbian Exposition, the grand Mecca was originally white-only, which changed along with the neighborhood as the Great Migration brought thousands of new Black Chicagoans fleeing the South’s Jim Crow laws and lynching in the early 20th century. Many arrived on the nearby Illinois Central railroad.

The massive Mecca covered nearly two acres and became a Bronzeville icon, but “fell into disrepair” per all accounts by mid-century. Here’s a 1951 exterior view from the Encyclopedia of Chicago:

The Mecca was razed in 1952 and replaced by Mies van der Rohe’s Crown Hall, to house IIT’s architecture school. So if you’re off on a Brooks field trip, you’ll have to stand in front of Crown, itself considered a modern architecture classic, and imagine the Mecca in its place.

The Mecca inspired the famous song “Mecca Flat Blues” by James “Jimmy” Blythe, as wells as Gwendolyn Brooks’ masterpiece poem. As Brooks fans know, during the Depression she worked for a Mecca resident who sold potions, and got to know the building well as she delivered orders to neighbors.

Chicago Cultural Historian Tim Samuelson curated an amazing 2014 exhibit, “Mecca Flat Blues,” on the fourth floor of the old Chicago Library, now Cultural Center. Check out a description and wonderful slideshow gallery of the exhibit here. It was quite something to behold.

Plus: Atlas Obscura features a terrific 2018 look at the Mecca by Hannah Steinkopf-Frank, sparked by discovery of Mecca artifacts which led to an archeologic dig around Crown Hall.

Extra Note on Lincoln Cemetery in Blue Island

Thanks to Twitter—how often do you read that phrase?—Lady Topham Catt and Chicago journalist Robert Loerzel also reminded me that Lincoln Cemetery is the resting place of Eugene Williams, the 17-year-old Black teenager who drowned off 29th Street when his homemade raft drifted into a white beach area and a white man threw rocks at him. His murder started Chicago’s infamous 1919 race riot.

Loerzel wrote a fascinating account of the 1919 race riot for Chicago Magazine on the 100th anniversary, and a deeper dive into Eugene Williams. At that time, Eugene Williams’ grave was still unmarked, 100 years later. Loerzel scoured the cemetery for it. He finally identified Williams’ plot—Section 5, Lot 30, Row 6, Grave 35—by verifying the name of the marked grave next to it. A group of concerned citizens subsequently raised $5,000 to finally memorialize Eugene Williams. The marker was put in place about two years later, delayed by the pandemic. Photos again thanks to Lady Topham Catt:

“Lincoln (Cemetery) is amazing for Black history,” Lady Topham Catt tweeted to me. “I won’t share everyone, but look for Lil’ Hardin Armstrong, a musical force to be reckoned with on her own, & for a time 1/2 of a jazz power couple (the other half was Louis Armstrong). Bessie Coleman, the first Black & Native American woman to hold a pilot’s license, though she had to go to France to get it. She also has quite the marker.”

Lincoln Cemetery was founded by Black businessmen in 1911, per Wikipedia, and the list there of prominent Chicagoans is a long one also including Daily Defender founder Robert Sengstacke Abbott, blues great Big Bill Broonzy, and Rube Foster, known as “the father of Black Baseball” for his role in the Negro leagues as a pitcher and founder/manager of the Chicago American Giants. For more on Rube Foster, check out the Chicago History Podcast, episode #504.

Addendum: Nicole Hollander’s “Sylvia”

I’ll never have another excuse for this, because “Sylvia” wasn’t syndicated and appearing in the Sun-Times until 1981. So here goes. I photographed the comic strips above from one of my prized literary possessions:

Thanks to Susan Figluilo, I got this priceless autograph.

Per the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, Nicole Hollander’s “Sylvia” officially began in 1979 and retired in 2012: “The Sylvia character is a combination of three witty West Side women: Hollander’s mother and her mother’s lifelong friends, Olga and Esther. This composite gave Sylvia, in Hollander’s words, ‘a rough-edged, Chicago sense of humor.’….It is not clear from the strip whether Sylvia is divorced, though she does have a daughter and an undefined relationship with a man named Harry. Hollander, in an interview with Women’s Voices for Change, called Sylvia, ‘like a 1940s dame.’”

“Sylvia” is that rare comic strip based on the politics and culture of its times which has aged extraordinarily well, which is a great commentary on the strip but perhaps a sad commentary of the current times. Respected? Oh my yes. One anthology has an introduction by Barbara Ehrenreich, another by Jules Feiffer.

You can get a daily Sylvia hit from Go Comics here. In putting this short bit together, I discovered—I’m embarrassed to say I was unaware—that Nicole Hollander published the graphic memoir “We Ate Wonder Bread: Growing Up on Chicago’s West Side” in 2018. I’m ordering it now. I just wish it was going to have a personalized cat cartoon on the inside cover.

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

Was not a huge Sylvia fan, but always loved the dogs from hell strips.