THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972: Nostalgia for John R. Powers' nostalgia

Literary Supplement #4

To access all website contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 is part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. Follow THIS CRAZY DAY on Twitter: @RoselandChi1972.

The first sentences of Chicagoan John R. Powers’ 1973 “The Last Catholic in America” belong right up there with “A screaming comes across the sky” or “Call me Ishmael.” Consider:

“I didn’t say good-bye to all my imaginary friends or do anything stupid like that before I went off to my first day of school,” wrote Powers. “Not that I didn’t have imaginary friends. At that time I had two, Joe Brown and Pete Brown. By the time I was fifteen, I had forty imaginary friends. I still hang around with a few of them.

“Joe Brown was the bartender in the upstairs bathroom. Joe was the owner and Pete was his assistant. Pete Brown got his own place when we put in a bathroom downstairs.”

And that’s before he even gets to the Catholic stuff.

Do I exaggerate? As always, you be the judge. But Powers fans will agree that he catalogued mid-century Chicago Catholic life as meticulously as Melville did 19th century whaling, and the resulting scenarios were as zany as anything conjured up by Pynchon, albeit Powers’ writing was always good clean fun.

John R. Powers chronicled what it was like to be a Catholic kid on Chicago’s South Side as realistically as James T. Farrell’s “Studs Lonigan,” and with a lot more laughs.

“Besides being under God’s constant surveillance, Sister Eleanor told the class that each one of us had his own personal guardian angel who had been assigned by God to do nothing but watch every move that was made by the kid whom the angel was told to guard,” Powers wrote of his first grade nun. “I already had double coverage and I hadn’t even reached the age of reason yet.

“On the days that Sister Eleanor was feeling a little fruity, she’d tell us to sit on one side of our desk seats so that our guardian angels would have room to sit down. We’d do it, too. We were as crazy as she was.”

I know what you’re saying: Why are we talking about a book that came out in 1973? But Powers wrote several pieces for the Chicago Tribune Magazine in 1971 and 1972 that were almost verbatim building blocks for his first book, including the piece from March 12, 1972 which we’ll excerpt today.

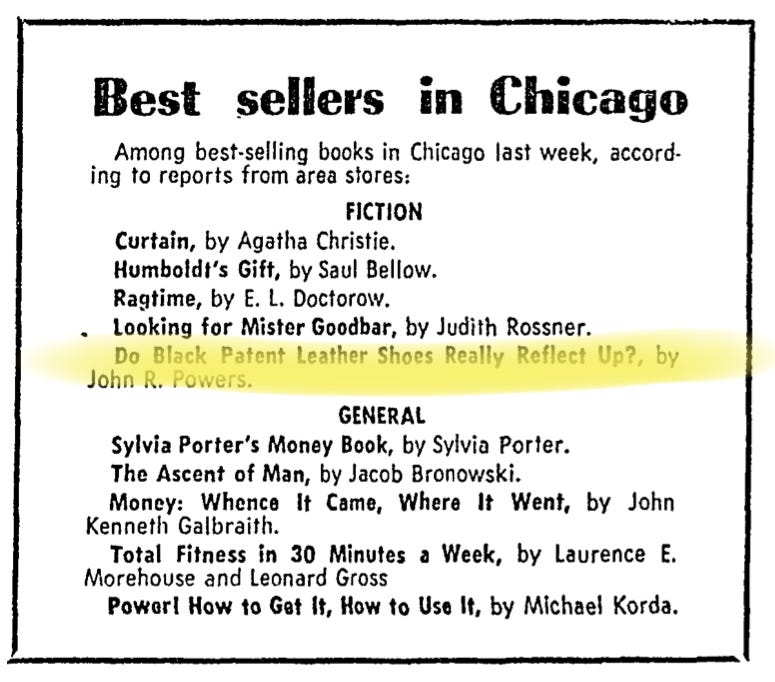

Although “Last Catholic” just missed our 1972 deadline, Powers’ three novels recounting his Catholic school days and neighborhood were an essential piece of the overall 1970s Chicago zeitgeist. “Last Catholic” and “Do Black Patent Leather Shoes Really Reflect Up?” tell the story of Eddie Ryan’s grammar school and high school years. “The Unoriginal Sinner and the Ice Cream God” follows Eddie Ryan to college but under a different name—which Powers himself later said “fooled no one.” As Maureen O’Donnell wrote in Powers’ 2013 obituary in the Sun-Times, “In the 1970s, the books of Mr. Powers became popular paperbacks that could be spotted in the hands of commuters on buses and L trains all over Chicago.”

In 1973, “The Last Catholic in America” was a revelation to 11-year-old Steve Bertolucci in the same way that Nelson Algren’s “The Man with the Golden Arm” affected Mike Royko.

Royko was floored as a young soldier in a tent in Korea when a pal tossed him Algren’s masterpiece, as he suddenly realized somebody could write a book about his neighborhood around Division and Milwaukee—including “the dopeheads and boozers and card hustlers.”

Don’t miss Mike Royko 50+ Years Ago Today

Steve Bertolucci, hero of the serialized novel at the heart of this Substack, was stunned to find somebody could write about a Catholic South Side neighborhood— and make fun of everything from nuns to confession. Wouldn’t that guy get in trouble? Wouldn’t he go to hell?

It was also confusing to Steve and his friends that “Last Catholic” was about a neighborhood called “Seven Holy Tombs,” which should have been due west of Roseland, but wasn’t there. The grown-ups explained that Powers was writing about Mount Greenwood, but then why didn’t he just say “Mount Greenwood”?

“Last Catholic in America” seemed so real to Steve and his pals, they came to believe, without thinking about it, that there was a Seven Holy Tombs, and a St. Bastion’s parish. It was easy. Even though Powers was writing about the early 1950s in “Last Catholic,” 20 years before Steve’s time, everything was basically the same, though it was fading fast.

The houses, streets, and stores of Seven Holy Tombs sounded just like Roseland and St. Anthony of Padua. Despite all the brouhaha about Vatican II changes after 1965, day-to-day Catholic existence didn’t suddenly whirl out of religious orbit just because Mass was in English and Lenten fasting became slightly easier. You still got baptized, made your first Confession and First Communion, got confirmed, and feared priests and nuns.

The Chicago Archdiocese in 1972—and 1973—was still the largest in the country, and Chicago newspapers followed the doings and pronouncements of the Pope as if he still commanded armies. Pope Paul VI made as many speeches as any politician.

Typical coverage of Pope Paul VI from the September 13, 1972 Daily News:

These days, we may forget how central the Catholic Church was to 20th century Chicago. The first Catholic baptism here took place in 1822; the first official Catholic church was built at today’s State and Lake by 1833; and the Diocese of Chicago was created in 1843. Catholics work fast: When the Great Fire swept through the city not quite thirty years later in 1871, the Catholic Church lost about $1 million in property. By 1892, according to the Chicago Catholic newspaper, “Chicago had become the most Catholic of American cities.”

John R. Powers never won a Pulitzer or a National Book Award. His books aren’t taught in literature classes. But he captured a specific, real world in more complexity than he gets credit for, in books that were simple enough for ten-year-olds to read and appreciate.

Powers was born in 1945 and raised in Mt. Greenwood, attending St. Christina’s for grammar school, Brother Rice for high school, and Loyola for college. He got his doctorate in communications from Northwestern, and became a speech professor at Northeastern.

Powers adapted “Do Black Patent Leather Shoes Really Reflect Up?,” his account of a Catholic all-boys high school, into a 1979 musical which ran three years at the Forum Theater. At that time, it was the longest locally-produced show in Chicago theater history. The show barnstormed the country with three productions running at one point.

“When I was in third grade, a nun walked up behind me and caught me making a sarcastic remark to a fellow student,” Powers told the Trib’s Clifford Terry in 1981, at the height of his musical’s success. “She slapped me on the back of the head and said, ‘Mr. Powers, if I were you, I’d spend more time with your books because you are never going to make a living with that smart mouth of yours.’ Of course, she was wrong. I make a very nice living with it.”

“Shoes” would go on to smashing failure on Broadway, however, closing in a week. “The critics were expecting a biting, anti-Catholic satire, and when they didn’t see it, they let us have it,” Powers told the Trib’s Richard Christiansen in 1987 as “Shoes” prepared to reopen in Chicago.

“Others have said that he keeps playing the same tune about Catholic nostalgia over and over,” wrote Terry, pitching that jab as a question to Powers.

“It could be true if I continued writing about Catholics—which I’d be surprised if I did,” Powers answered. “Still, presuming I’m good at what I do, that’s like saying, ‘Johnny Carson is a good talk-show host, but can he dance?’ It’s, ‘Powers is good writing about Catholics, but can he work in the Ford assembly line as a welder?’ Who cares? Besides, I write a lot of neighborhood humor, which has nothing to do with Catholicism.”

The other common criticism of Powers’ books is that they’re too light, too sweet, or too nostalgic. Novelist William Brashler had a different take on that when he reviewed “Shoes” the novel in 1975 for the Daily News. Brashler, author of the acclaimed “The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings” and “City Dogs,” grew up in Michigan but worked in Chicago at Lerner Newspapers in the ‘70s.

“Imagine,” wrote Brashler, the “delight of devout and lapsed Catholics…when they discover that John R. Powers’ second book is as funny as his first….As likable and outrageous as the book is, it finally points an accusing finger at Powers. He seems satisfied for the most part to run with his wit and his anecdotes in what is a comfortable achievement. But the book’s very excellence nags for something better, more, something that would make a difference.

“Although it is a mortal sin to criticize a book for what it isn’t, Powers’ work asks for it. I think he is good enough, controlled enough, the master of his fictional voice so that he could have put together his own ‘Catcher in the Rye’ or ‘Confessions of a Spent Youth.’

“There are many scenes in ‘Patent Leather Shoes’ that prove it. They are often touching, insightful, and damn memorable, and they give the book its breadth when the one-liners run out. In writing these as well as he does, Powers signals that he may be ready to finish off his entertaining trysts with his past in favor of a full-blown treatment of the present. Here’s one reader who’s waiting for it.”

Did Powers rise to the height Brashler envisioned for 1977’s “The Unoriginal Sinner and the Ice Cream God?” Hm, no. It’s worth reading, but no.

Rick Kogan pretty much hated it.

“This latest novel by Chicagoan John R. Powers is not a novel at all,” Rick wrote in a blistering review. The lead character’s life, Rick wrote, “flashes before us like a Henny Youngman routine: fast and forgettable…Powers is a fine humorist with a deft touch. But in this latest effort he is just clever and cute. His story becomes superfluous. For a writer there can be no greater sin.”

Henry Kisor, who would go on to be the Sun-Times book editor for years, also panned “Unoriginal Sinner” in a 1977 overview in the Daily News:

“John R. Powers is a fine South Side Irish comic writer, but he faltered badly in his third novel, ‘The Unoriginal Sinner and the Ice Cream God,’ in which his attempts to answer cosmic questions had all the substance of Woolworth-counter nostrums.”

However, per a John Schulian Daily News column on Bill Veeck that year, “Unoriginal Sinner” delighted that Chicago icon. And, like Powers’ first two books, “Sinner” was a Chicago best seller.

Still, it’s true that John R. Powers is not a Nelson Algren, a Saul Bellow, or a Gwendolyn Brooks. He’s also not, say, Stuart Dybek, an acclaimed Chicago writer of the his own generation. So why did Powers strike such a nerve with Chicago readers?

EXTRA CREDIT: If anybody can tell me the address of John R. Powers’ childhood home in Mt. Greenwood, it’s worth a fabulous, like-new Jays Potato Chips pencil. I know Powers lived on Drake—but where? It seems wrong not to have a picture of the real home of Eddie Ryan in this post. Let me know in comments, or RoselandChicago1972@gmail.com.

UPDATE: Thank God for readers. Vicki Quade, intrepid co-creator of Late Nite Catechism—see below for more —immediately had the good sense to look in an online 1950 Chicago phonebook and found the Powers address, so I was able to update a general picture of South Drake with the Powers home earlier in this post. Here’s the phonebook listing, which may interest Younger Readers unfamiliar with such things. Waiting to hear if Vicki wants that pencil, because she may already have a houseful: It turns out her dad’s cousin was Leonard Japp, and her father came to Chicago to work for his cousin at the beloved Jays factory.

“There aren’t a lot of other writers who focused on the Catholic upbringing, and Chicago is a very Catholic city,” said Vicki Quade when I called to ask her, and she should know. Quade, who grew up very Catholic in southwest suburban Burbank, is the Chicago treasure who brought us “Late Nite Catechism,” a show that opened in 1993, ran seven years off-Broadway, and is still playing literally here, there and everywhere. “You write what you know, and he knew that Catholic upbringing,” said Quade. “It was a time when you didn’t identify yourself by your address. You didn’t even say your neighborhood, you said your parish. ‘I live in St. Christina’s.’”

“A lot of people identified with his work,” Quade went on, “because that’s the culture of Catholicism, and if you ask why does his work resonate, because we have that cultural Catholicism and it’s worldwide. It isn’t just a Chicago phenomenon.”

“Late Nite Catechism,” Quade relates, has played in places like Singapore and Australia. “When we were in Melbourne, at the end of a performance, a woman came up to me and said, ‘I’m from the bush, and you’ve written about my life.’”

Quade agrees with Powers critics who think his work is nostalgia—but she doesn’t think it’s criticism. She thinks it’s a good thing.

“You go back to your childhood for everything,” she pointed out. “If you have an emotional issue, when did it start? When you look up friends on Facebook from 50 years ago, that’s to connect with them, because you have the same upbringing and memories. Memories are so strong in entertainment. If you can connect somebody with a memory, I think that’s great. Nostalgia’s good.”

And now…from the March 12, 1972 Chicago Tribune Magazine, excerpts from John R. Powers’—

—which readers of “Last Catholic in America” will recognize as Chapter VII: Lent.

“In Catholicism, the name of the game was pain. The more one suffered the higher he got in heaven. After all, Christ, Who began the whole thing, was a great connoisseur of pain. He started off by being born Jewish. That, in the eyes of most Catholics, is a fair amount of pain right there.”

….

“Christ led the life of a loser. It was an existence of persistent, pounding, penetrating pain. He was the first Catholic and we all faithfully followed in His footsteps.

“The members of St. Trazer’s Parish, located on Chicago’s South Side, suffered constantly and loved every second. Stubbed toes, cars that wouldn’t start, ruptured appendices, rainy weekends, and scraped knees were all moments of misery that the parishioners savored.

“According to the rules, the more suffering you did on earth for your sins, the less you would have to do in purgatory.”

….

“Altho pain was a year ‘round pastime at St. Trazer parish, the apex of agony was those 40 days before Easter: the 960 hours of Lent when the pain of simply surviving on the South Side fell far short of the sacrifices necessary for salvation….

“Lent was a time of ‘give-ups.’ At the beginning of the 40 days, fathers would give up smoking and swearing, mothers would give up nagging, and children would give up sweets. A few more weeks and we’d all give up….

“About the only people who kind of looked forward to Lent were the fat Catholics. Thruout the Lenten period, everyone between the ages of 21 and 59 was allowed to eat meat only once a day. Snacks between meals were also prohibited. In addition, two of the three daily meals could not equal in size the main daily meal. Of course, if you ate like a savage at your main meal, you could still manage, within the rules, to gorge yourself two more times a day and still remain in good standing with the Church.”

….

“During Lent, we kids at the parish school had to attend the 8 o’clock mass every morning before going to class. On Wednesday and Friday afternoons, we had to go back to church after school and sit thru an hour-long Lenten service….

“An after-school Lenten service included, among other things, a journey through the stations of the cross. A stations of the cross consisted of 14 illustrations depicting the story of Christ’s crucifixion, from His agony in the garden to the time His body was placed in the tomb.

“During the Lenten services, as the priest made the stations of the cross, he would stop and stand in front of each station, holding a cross which was mounted on a staff. An altar boy, holding a candle, would stand on either side of him.

“The priest’s words would meander thru our minds as he explained a particular station of the cross, his voice giving emphasis to the pain points. He didn’t make any of this stuff up. He read it all out of a little blood-red-covered pamphlet. Each kid in the church also had a little blood-red-covered pamphlet so we could all read and shudder along with him….

“‘The 11th station of the cross,’ the priest would cry out as he began reading from the blood-red pamphlet. ‘Jesus is nailed to the cross. Mary, holy mother of Jesus, is pierced anew as she sees wells of her son’s redeeming blood dug in His hands and feet by the nails of the cross. Oh, Mary, thru Jesus’ wounds, help me renew my baptismal vows and with those nails bind me to Jesus forever.

“‘Forgive me, oh, Jesus,’ the priest would continue to read from the pamphlet, ‘for I know that it is my sins that have put You on that cross. I realize, dear Jesus, that each time I disobey my parents, each time I lie, each time I don’t listen to the good sisters and priests, I am driving the nails deeper into Your hands and feet.’

“Besides being held personally responsible for Christ being crucified twice a week, Wednesday and Friday afternoons at 3 o’clock, each kid at St. Trazer’s was expected to ‘give up’ something for Lent.”

….

“‘I think, children,’ the nun said to us as we began getting ready to go home, ‘that you should all give up something of real importance for Lent this year to show God how sorry you are for the sins you’ve committed against Him. Remember, it’s your sins that put Christ up on that cross.’ She looked solemnly up at the crucifix that hung high on the classroom wall and then back at us. ‘Tomorrow is Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent, so tonight is your last chance to tell God what you’re going to give up for Him during Lent.’ The meaning of her words was clear. Don’t goof it up.

“On the way hone from school, I asked myself, could I give it up for 40 days? I looked down at it. My mother had been after me to quit. My father had warned me that if I didn’t break the habit I’d be socially retarded, whatever that was. Our family doctor insisted that it was loaded with germs and that I’d ruin my health. my dentist said I’d get ‘buck’ teeth. But I liked it. It was an inexpensive, convenient, and tasty habit. I thorny enjoyed sucking my thumb.”

Find out if Eddie makes it for 40 days! I see that on Amazon, you can purchase “Last Catholic in America” for $10.99 on Kindle, while I’m shocked to say a hardcover will run you at least $47.57. If you live in Chicago, I bet you can get the paperback at a used book store like Powell’s. But maybe I’m wrong. There are only 15 copies on eBay, and the cheapest is $17.88 for the paperback.

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.