THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972: Christmas Comes Early for White Sox Fans

November 29-December 5, 1971

To access all site contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 was part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. If you’d like, keep up with the 1972 papers every day on Twitter, @RoselandChi1972.

November 29, 1971

Chicago Daily Defender: Teen gospel singer shot dead

By Tony Griggs

Young bass singer John Blake Jr. was shot early Sunday morning as he arrived home in Rockwell Gardens at 2450 W. Monroe following choir practice at his cousin’s home. The “Love Specials” gospel quartet was supposed to perform Sunday afternoon for its second anniversary at Holy Temple Missionary Baptist Church, 2142 W. Van Buren.

Suspect Gregory McGowan, 19, allegedly shot 17-year-old Blake “in the back of his head after the victim reportedly refused to give up his new, multi-colored suede coat.” Several witnesses identified McGowan, who was wearing Blake’s coat when arrested.

Blake lived with his widowed mother and four sisters, attended Crane High School, and worked evenings at Illinois Children’s Hospital-School to help out at home. Mrs. Eva Geanes, Blake’s aunt, said he was “a church-working boy” following in his family’s footsteps as a gospel singer.

November 29, 1971

Chicago Daily Defender: Abernathy wants answers; Jesse, Todd mum on SCLC probe

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference is investigating whether the Rev. Jesse Jackson Jackson formed a nonprofit foundation and a nonprofit corporation to put on Black Expo ’71, held at the International Ampitheatre in October, without getting necessary permission from SCLC.

Thomas Todd, president of SCLC’s Chicago branch, and Jackson, national director of SCLC offshoot Operation Breadbasket, wouldn’t comment. SCLC national president Rev. Ralph Abernathy ordered the investigation to “check reports that the Expo, the foundation and the corporation were formed without either his knowledge or SCLC’s board of directors.”

“Mr. Abernathy conceded that he had avoided confrontation with Mr. Jackson about not following policies of the national organization previously, because the ‘freedom movement was at stake’ and he felt that was what the white power structure would need—to see internal strife within the most vibrant civil rights organization in the country.’”

But, Abernathy added, “We cannot at this time allow a department to get out of line. It can hurt the entire organization.”

November 29, 1971

Chicago Tribune: Bears in ‘Super-Must’ TV battle with Dolphins

By Cooper Rollow

This is the Bears’ very first appearance on Monday Night Football, which just started in the 1970 season. It’s the Bears’ first regular season match against the Dolphins, too. The Bears have to win every single game the rest of the ’71 season to make the play-offs.

Problems: Dick Gordon might still be out tonight. Miami’s Orange Bowl’s “PolyTurf” field “has a tendency to become slippery when there is the slightest hint of moisture in the air.” And the Dolphins are formidable.

Rollow writes that Miami “includes the top passer in the league, Bob Griese; the foremost place kicker, Garo Yepremian; the most prolific pass receiver, Paul Warfield, and a pair of running backs who won’t quit, Larry Csonka and Jim Kiick.”

“But,” Rollow concludes, “the Bears will show up.”

November 30, 1971

Chicago Daily News: Bears humiliated, confused

By Ray Sons

Chicago Tribune: Dolphins Destroy Inept Bears 34-3

By Cooper Rollow

“All of their castles in the sky came tumbling down upon the Bears Monday night,” writes Ray Sons. The Bears lost 34-3—on their very first appearance on the nationally-televised, really big deal Monday Night Football.

“And now it is time to say, ‘Wait ‘till next year.’” This was the Bears’ fifth loss this season, “but the first in which their proud defensive team had been humiliated,” writes Sons.

More from the News: “Dick Butkus said: ‘We just got beat by a better team.’ Doug Buffone was candid: ‘We got the (censored) beat out of us.’ Willie Holman used the same pungent language.”

The Bears are out. Their only score was a field goal in the third quarter as they trailed 27-0, drawing derisive boos from the Miami fans.

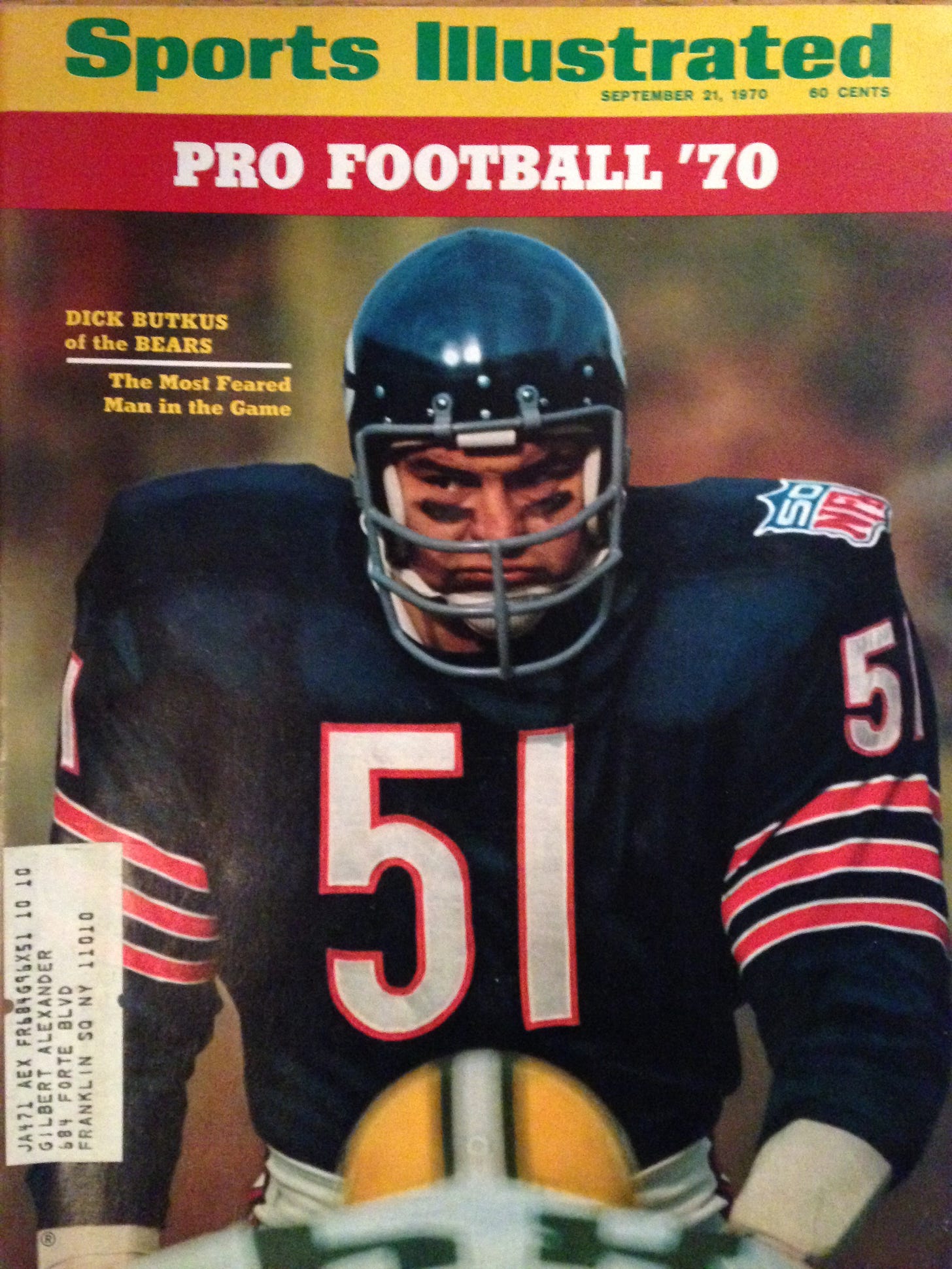

“The Bears, if possible, played even more poorly than they had last week against Detroit,” writes the Trib’s Cooper Rollow. “But don’t believe the Three Wise Men on television who made excuses for linebacker Dick Butkus, saying his physical condition hampered his play.”

The Three Wise Men are the stars of the still brand-new Monday Night football, Howard Cosell, Frank Gifford and Don Meredith. Rollow writes that “It wasn’t Butkus’ fault that the Dolphins poured around the Chicago flanks like hordes of Chinese infantrymen, riddled the Bear pass defense, and in general pushed the Bear defenders around as if they were toying with an army of plastic soldiers.” It sounds sarcastic, but I doubt it, because all the sportswriters clearly feel Dick Butkus cannot be wrong or play badly, ever.

Bobby Douglass has forgotten everything he learned when he and Coach Jim Dooley played “Odd Couple” with Dooley living at Douglass’ apartment before the earlier Lions game, says Rollow. He “completed nine of 27 passes for 111 yards. But he served up three interceptions and was forced to go to his safety valve backs on numerous occasions when he could not find the secondary receivers.” (Ironically, Howard Cosell will make several appearances on the then current hit sitcom “The Odd Couple.”)

On the other side, writes Rollow, “Griese, pro football’s leading passer, clicked on 12 of his 17 aerials for 214 yards and two touchdowns….Garo Yepremian chipped in field goals of 43 and 35 yards, and Csonka bulled over from 2 yards out. Csonka and Kiick, his running mate, terrorized the Bear defense by romping for a total of 175 yards.”

November 30, 1971

Chicago Tribune: Butkus calls Miami “One of best ever”

By George Langford

Dick Butkus (proud son of Roseland!) is so revered that even though the Bears’ defense led by Butkus was humiliated during the 34-3 loss to Miami on Monday Night Football, the newspapers cover it with a twist:

“Dick Butkus’ praise for an opponent usually consists of a grudging shrug of his massive shoulders,” writes George Langford, “but tonight even the man who more than any other player personifies the violent nature of football readily admitted to the Miami Dolphins’ greatness.”

Butkus is at once the greatest, and possibly greater for admitting the Dolphins were greater.

“They bottled up our defense on the draw plays and Griese had some scramble plays that really hurt but I don’t know exactly where our breakdown was,” Langford quotes Butkus. “They just outplayed us and they were very good.”

Bears coach Jim Dooley—and everybody else—predict the Dolphins will take a turn at the Super Bowl.

December 1, 1971

Chicago Daily News front page, top headline: Daley, Ogilvie, board to meet: School aid ‘summit’ set

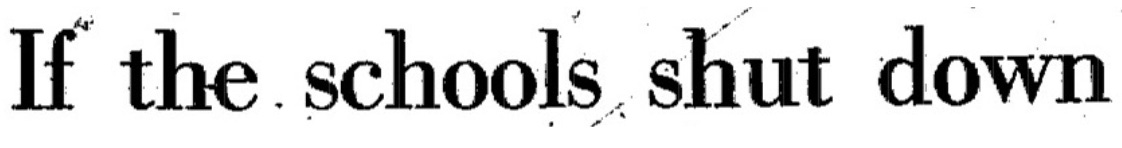

Chicago Daily News editorial: If the schools shut down

Chicago Public Schools have threatened to close 12 days early for Christmas vacation because they’re out of money, with a $26 million deficit for 1971. Next year looks worse—a projected $62 million deficit in the 1972 budget. Mike Royko writes a hilarious column on this today—see the weekly compilation of MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY for that.

You’ll need some background on this to appreciate the powerful Daily News editorial conclusion. So here goes: Teachers plan a massive march and rally against closure at the Civic Center Plaza—that’s now Daley Plaza—today after school. The Rev. Jesse Jackson, who’s always involved in major issues like this and currently runs the SCLC’s Operation Breadbasket here, says he may organize mass demonstrations too. Breadbasket is looking for volunteer teachers and temporary locations to hold class in Black communities.

So the school funding crisis is quite a big deal. Schools could shut down a week from today. On Monday, Board of Education president John Carey asked to meet with the real Mayor Daley, who received school officials in his City Hall office.

After meeting Mayor Daley, board member Warren Bacon tells reporters, “We got a lot of ideas but no money.” Bacon blamed the school crisis on Mayor Daley when he spoke to an Operation Breadbasket audience recently. But after meeting with Daley, Bacon says it’s “not the mayor’s fault.” Mayor Daley is a political Obi-Wan Kenobe. You can just picture him behind his desk sputtering, “This isn’t the funding source you’re looking for!”

Now Board President Carey says the point of the Daley meeting was “to convince the governor that the state must help. It is evident from the mayor’s budget problems that the money is not going to come from the city.” The Board was supposed to vote on school closure on Friday, but instead Daley and some Board members will fly to Springfield Friday to meet with Illinois Governor Ogilvie.

Daley reportedly favors the Board borrowing its way out of this—and the Teachers Union supports borrowing. The Board is divided. One Board member quoted today says they’re already going to be in debt $62 million in 1972, “and I can’t see much difference if we added another $20 million.” Jesse Jackson says teachers should go to work regardless: “Teachers have a moral responsibility to teach without pay.”

Prospects for the Ogilvie meeting are dim. Last week, Ogilvie said, “They’d just ask me for more money again and I’d turn my pockets inside out to show that I don’t have any.”

On Monday, Board President Carey said he wanted to meet with Mayor Daley “because of his successful mediation of a teachers’ union contract last January”. Today the Daily News editorial says Mayor Daley’s deal with the teacher’s union caused the whole problem. The editorial says the strike “was settled on terms that guaranteed a deficit.”

“Since then,” says the News, “the system has been running on hope—hope that the state would provide more money or, failing that, the city would bridge the gap.” And when Daley settled the teacher’s strike, “he confidently predicted that the money would be available to pay the increased salaries.”

The most “galling” thing is ongoing waste by the School Board and the city, says the News. “Just this week Ald. William Singer (43rd) issued a report that indicated $500,000 is being uselessly spent by City Council committees. He was labeled a ‘kook’ by fellow aldermen.” Singer is one of the few independent aldermen in Mayor Daley’s council.

The editorial’s blunt conclusion:

“The interlocking system of political favoritism and patronage that runs Chicago and its schools is clearly a costly one. But when it comes to a choice between paring down that system and turning the children out of school, it’s the children who lose out….In a town that’s run by clout, the only way to beat the system that puts children last is to get more clout.”

December 1, 1971

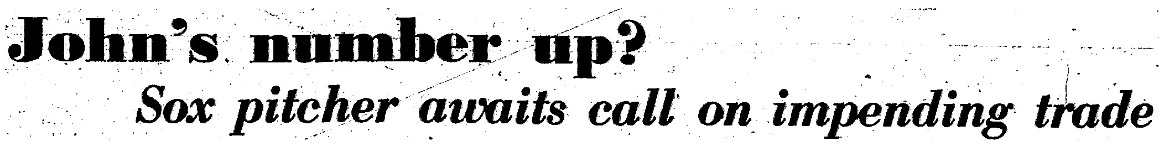

Chicago Daily News: John’s Number Up? Sox pitcher waits call on impending trade

By Dave Nightingale

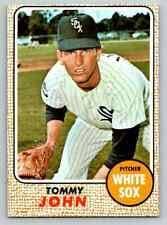

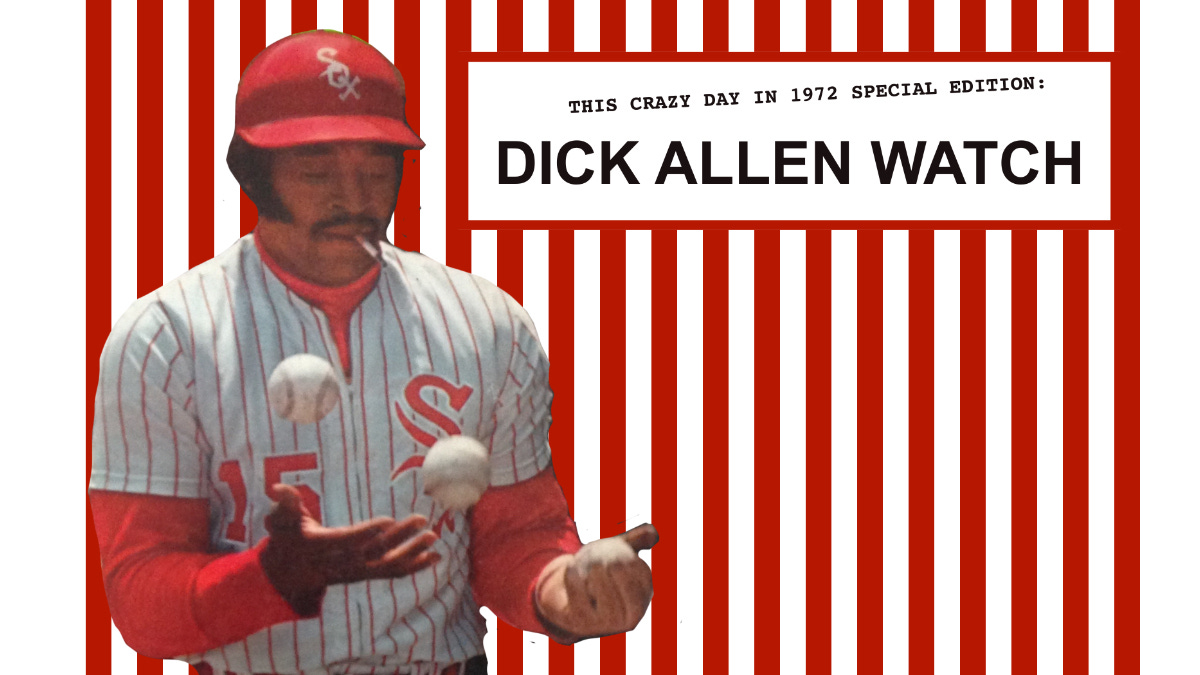

Sox fans know why Tommy John inaugurates this new special recurring edition of THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, Dick Allen Watch.

Dave Nightingale knows how to ratchet up the drama with this lede:

“The phone is white and it is attached at head height to the ivory-colored wall in the den of a seven-room ranch house in suburban Scottsdale.”

“Eight miles away, in the Arizona Biltmore Hotel owned by P.K. Wrigley, officers of the 24 major league baseball teams are meeting.” An official from any of those teams except the Sox “is expected to dial 949-1814 this week and say: ‘Tommy, you’ve just been traded to our ball club.’”

Tommy John says he tries not to think about it—he’s been happy in Chicago, but he knows he’ll be traded. “It’s logical,” writes Nightingale. “The Sox need a center fielder. And everyone needs a good left-handed pitcher.”

The Sox wanted Rick Monday, but the Oakland A’s traded him to the Cubs for Ken Holzman. (Oddly, Nightingale doesn’t mention that Holzman had to go now that the Cubs are keeping Leo Durocher for the 1972 season, and the two don’t mix.) The Sox would like Jim Northrup from Detroit, or Al Oliver from Pittsburgh. But there’s no telling what’s going to happen.

Tommy John “spent the past week digging a trench around the kidney-shaped swimming pool in his back yard. Wednesday, he began to spread 12 tons of crushed rock in the trench. He attacks manual labor with the ‘skill’ of a left-handed pitcher. Last week, for instance, he stumbled over the pool foundation and ripped open his leg all the way to the bone, necessitating a trip to the hospital emergency room and some quick stitches.”

For now, we leave Tommy John waiting by the phone. And pause to marvel that there was a time when top professional athletes did their own landscaping work.

December 1, 1971

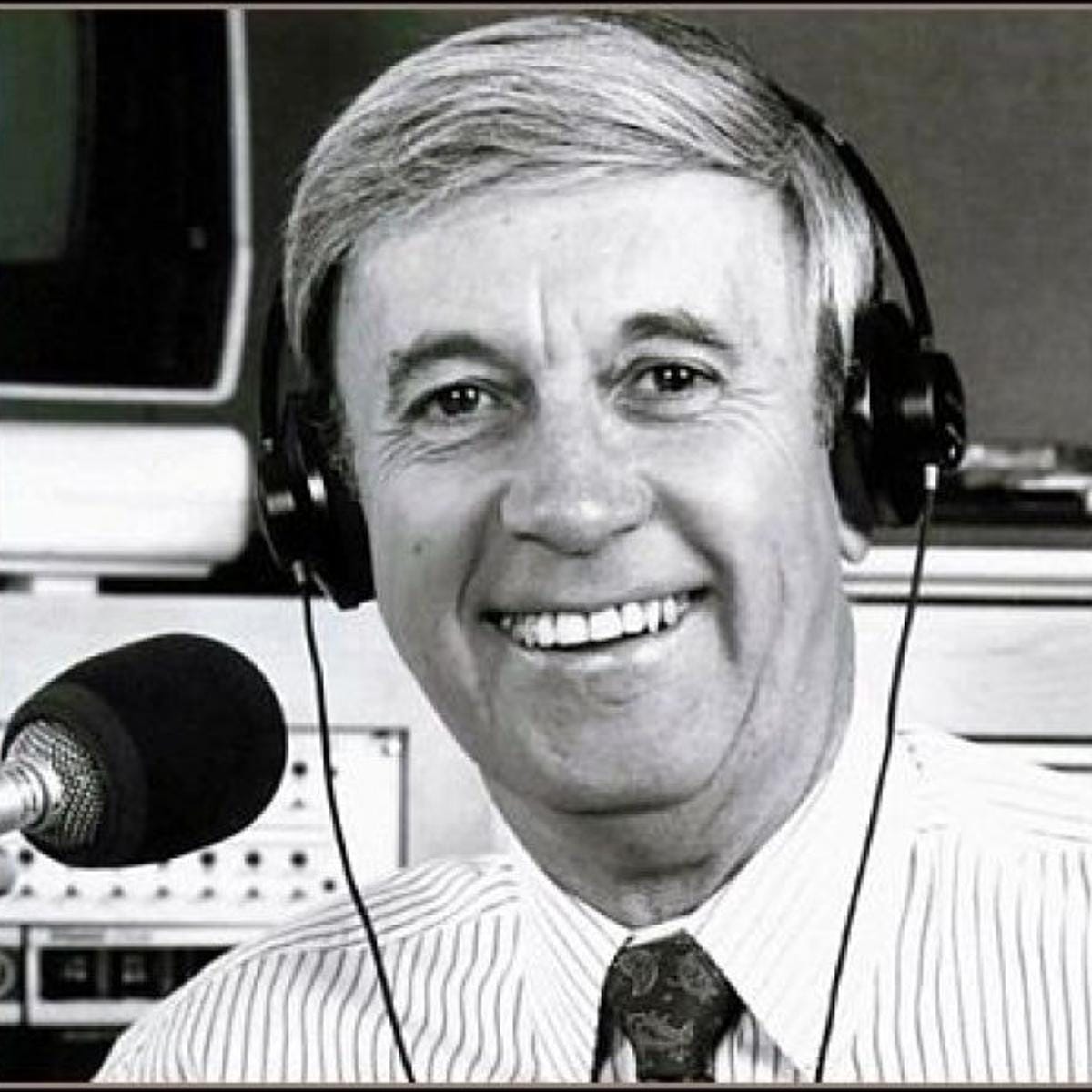

Chicago Daily News, Norman Mark column: Radio’s Wally Phillips ‘holding out’ for live TV

There was a time—and it certainly includes 1972—when you could walk down the streets of many neighborhoods on a summer morning and follow Wally Phillips’ radio show on WGN, unbroken, through the screened windows and doors.

Two reasons: Few people had air conditioning yet, and Wally Phillips controlled a 23% share of the radio audience in his time slot, 6 – 10 AM. Yes, literally one in four people in WGN’s vast radio range listened to Wally Phillips—over 1.6 million people.

And that’s 1.6 million in a concentrated, single area at the exact same time—not a disparate group of people spread out across the country or world, listening or watching when they feel like it on a phone or computer. It’s a totally different thing.

That’s why Daily News TV/radio critic Norman Mark sat down with Wally “over a good lunch while drinking some French wine” and wrote an entire column without one critical word. I won’t criticize Wally Phillips either. Wally Phillips was simply Wally Phillips. You might as well criticize the sky.

Mark says “Phillips began in Chicago as the funniest man in town. His show was filled with odd voices and quips. Later he became Chicago’s ombudsman, using the telephone and his radio show to solve problems. Now his show is a mixture of the two formats.”

He’s right: There was nothing Wally Phillips couldn’t find out, or solve; nobody he couldn’t get on the phone, and all during his four-hour show. Norman Mark seriously writes that Wally could probably call for Mayor Daley’s impeachment.

Wally Phillips was a ubiquitous presence in Steve’s house at 12426 S. Wabash in Roseland. In fact, Steve turned to Wally in a moment of personal crisis—covered in Chapter 7, yet to come. For today, a few points from Norman Mark’s December 1 column:

With his huge audience, Wally has been offered a TV show, but “I’m holding out for a live show. If a TV show is predictable, it isn’t any good.” Over lunch and wine, Wally speaks of a live show broadcast in a theater with local acts and top stars, “perhaps even a Picturephone so that Phillips’ loyal audience could call in and be seen.”

I see now that Wally thought he would become like a local Ed Sullivan, or even another national Ed Sullivan. Instead he ruled Chicago’s mornings for 21 years.

“Phillips strives to inform and entertain his listeners,” writes Mark. “He’s the kind of man who wants to look back after a week, a month or a life in broadcasting and be able to say he helped the world become a little bit better.”

And that’s true. As corny as Wally Phillips was, that was true—and it meant something.

December 2, 1971

Daily News: Richie Allen to Sox for Tommy John!

“Expect no problems,” says manager Chuck Tanner

Newspapers don’t use exclamation points very often in headlines—the giant black letters are considered sufficient to get your attention. But when Richie Allen (Dick Allen) arrives to save the White Sox, that deserves extra emphasis.

Note the headline is as big as it gets—front page, above the Daily News masthead. This is Pearl Harbor level coverage. There’s nothing today from the Sun-Times or Tribune, both morning papers that couldn’t get this giant story into today’s editions. Sadly I didn’t get to the afternoon Chicago Today microfilm for this.

Younger readers, and those who aren’t long time baseball fans, might wonder: Which is it—Richie Allen or Dick Allen? And why did the Daily News headline include a quote from Sox manager Chuck Tanner—“Expect no problems”? The answers are somewhat interwined and we’ll cover these topics more in the coming year.

Short answer on the name for now: Dick Allen prefers “Dick Allen” but got stuck with “Richie” professionally. Chicago media will finally shift to “Dick” later in his Sox tenure. Back on April 21, 1971 A.S. “Doc” Young wrote about this in his Chicago Defender column “Good morning, Sports!” “The baseball star most people call ‘Richie’ Allen prefers to be called ‘Richard’ (his given name) or ‘Dick’ (the nickname most of his friends call him),” writes Young. “But he won’t protest if he’s called Richie—a name he associates with some of the unpleasantries of Philadelphia.”

Re Chuck Tanner’s cryptic headline quote: Allen’s baseball career has been controversial, particularly his early years in Philadelphia. Today the News covers Allen’s history in the main story, AND they run an entirely separate, longish unbylined piece on this subject alone, headlined “Allen calms down.”

Main story: “PHOENIX--The White Sox took the big plunge in the trade markets here Thursday, acquiring slugger Richie Allen from the Los Angeles Dodgers in exchange for lefty Tommy John and utility infielders Steve Huntz,” writes Dave Nightingale.

“Allen, the sometimes controversial infielder-outfielder, hit .295 for the Dodgers last season with 90 RBI and 23 home runs. He stole eight bases in nine tries. Richie has played for three different teams in the last three years…and once drew the ‘curse’ of ex-Phillie manager Gene Mauch, who said: ‘No team that has Richie Allen will ever win the pennant.’”

But Sox manager Chuck Tanner, who grew up 20 minutes away from Allen’s home in Wampum, PA and knows Allen, says: “I only judge a man by what he does for me, not by what I read in the newspapers. He is a quality man…I’ve never seen him give less than 100 per cent of himself once the game starts. He’s the type of hitter who, just by his presence, can make better hitters of some of our other players.”

Companion piece lede: “In Richie Allen, the White Sox are getting one of baseball’s most controversial characters.” It’s mostly from “his stormy seven seasons in Philadelphia” where “Supposedly, he cost two managers (Gene Mauch and Bob Skinner) their jobs.” Still, Allen’s behavior has been “exemplary” in recent stops in St. Louis and LA.

Allen’s most notorious Philly episode was a fight during batting practice with fellow player Frank Thomas, a seminal event that turned many fans against Allen and affected the rest of his career and life. That happened in 1965, when Allen was just 23.

All the complex factors can’t be covered today. There were misunderstandings, Frank Thomas was a jerk who liked to bug other players, the Phillies should have handled the aftermath better, and tense 1965 race relations meant that a goodly contingent of white fans took the side of Thomas (white) over Allen (Black). This was the baggage Sox fans saw Allen bring with him to Chicago in 1971.

Today’s News quotes Allen after his 1970 trade to St. Louis: “I’m no troublemaker. I’m just human, same as anybody. They gave me the rap in Philly for everything except what I was paid to do, play ball.”

Allen’s career would end sadly early at age 35. A Philadelphia Inquirer analysis by Frank Fitzpatrick said in 2015, “Though truncated by injuries and often-mysterious absences, his career numbers of .292, 351 homers and 1,119 RBIs cause many Sabremetricians to rate Allen baseball’s best player between 1964-73, a talent-rich era when pitching dominated.”

Dick Allen died in December 2020, still not included in Baseball’s Hall of Fame. In 14 years of regular voting by baseball writers, Allen’s share never got above 16.7%--and you need 75%. But the Golden Days Era committee meets December 5, 2021, and Allen is again on the ballot. Allen fell one vote short on his last Golden Days shot in 2014. The December 2015 vote was postponed due to Covid, and Allen died that month.

Allen co-wrote a biography with Tim Whitaker in 1989, “Crash: The Life and Times of Dick Allen. And a brand-new book about Dick Allen and the 1972 White Sox comes out soon by veteran writer/producer and Tribune alum John Owens with Dr. David Fletcher and George Castle, “Chili Dog MVP: Dick Allen, the ’72 White Sox and a Transforming Chicago.” You can pre-order it here.

December 2, 1971

Chicago Sun-Times: Report on ‘the king,’ Butkus wounded and slowed

By Jack Griffin

Chicago sportswriters were not amused by Monday Night Football’s Howard Cosell, Frank Gifford and Don Meredith during the Bears’ humiliating defeat to the Dolphins 34-3.

“The Bears, if possible, played even more poorly than they had last week against Detroit,” the Trib’s Cooper Rollow wrote Tuesday. “But don’t believe the Three Wise Men on television who made excuses for linebacker Dick Butkus, saying his physical condition hampered his play.”

Today, the Sun-Times’ Jack Griffin attacks the TV trio. Monday Night Football began in 1970, but 1971 is the first season for the soon-to-be iconic Cosell-Gifford-Meredith announcing team. It’s a passionate, furious column from Griffin, so heartfelt that you see the contradictions and don’t care—you just want Griffin to really give it to those fancy schmancy TV stars.

“During these several years he has been the king of his jungle and they fled before his roar, but now he is wounded and the jackals have come to howl at Dick Butkus,” Griffin starts. “They do it with some timidity and at a safe distance…”

Like Rollow, Griffin won’t even name Cosell-Gifford-Meredith. “The other night some introspective fellows who look at this game with the magic box called television discovered Butkus was hurt, and that he did not always move with the alacrity that marked his maneuvers in other days,” Griffin sneers.

“Last Monday night in Miami one of the three comics who share a television booth announced nationwide that Butkus wasn’t playing with his old animalistic gusto. He modified this later by saying Dick was coming off knee surgery, but the implication was that people could start running over Butkus without fear of retaliation.”

Griffin has to admit Dick Butkus has physical issues, and now he does. Butkus had right knee surgery last January for loose ligaments. Butkus “obviously has not been able to play full capacity the last three games. Not just because of the knee. He wears a lot of injuries…You’re damn right he’s been playing hurt. I can’t remember when Butkus wasn’t playing hurt…And there’s been pain in him almost every game I can remember.”

“But don’t get any wrong ideas. Seventy-five percent of Dick Butkus still is better than any linebacker in the lodge. It’s impossible to miss Butkus on a playing field. By the time the whistle blows he is so damn mad he shakes with his ferocity.”

“If there is anything wrong with Butkus, and there isn’t” writes Griffin—even though he has admitted there are many things wrong with Butkus—opposing players still fear Butkus and build their entire offensive strategy off staying “out of his clutches.” “Dick may be only about 75 per cent healthy, but I have never seen him play football any less than 100 per cent.”

“If those three guys had stopped tickling their own ribs long enough in the television booth they might have noted that Butkus made 13 tackles in the Miami game. He must have been getting to some of the right places on time.”

December 2, 1971

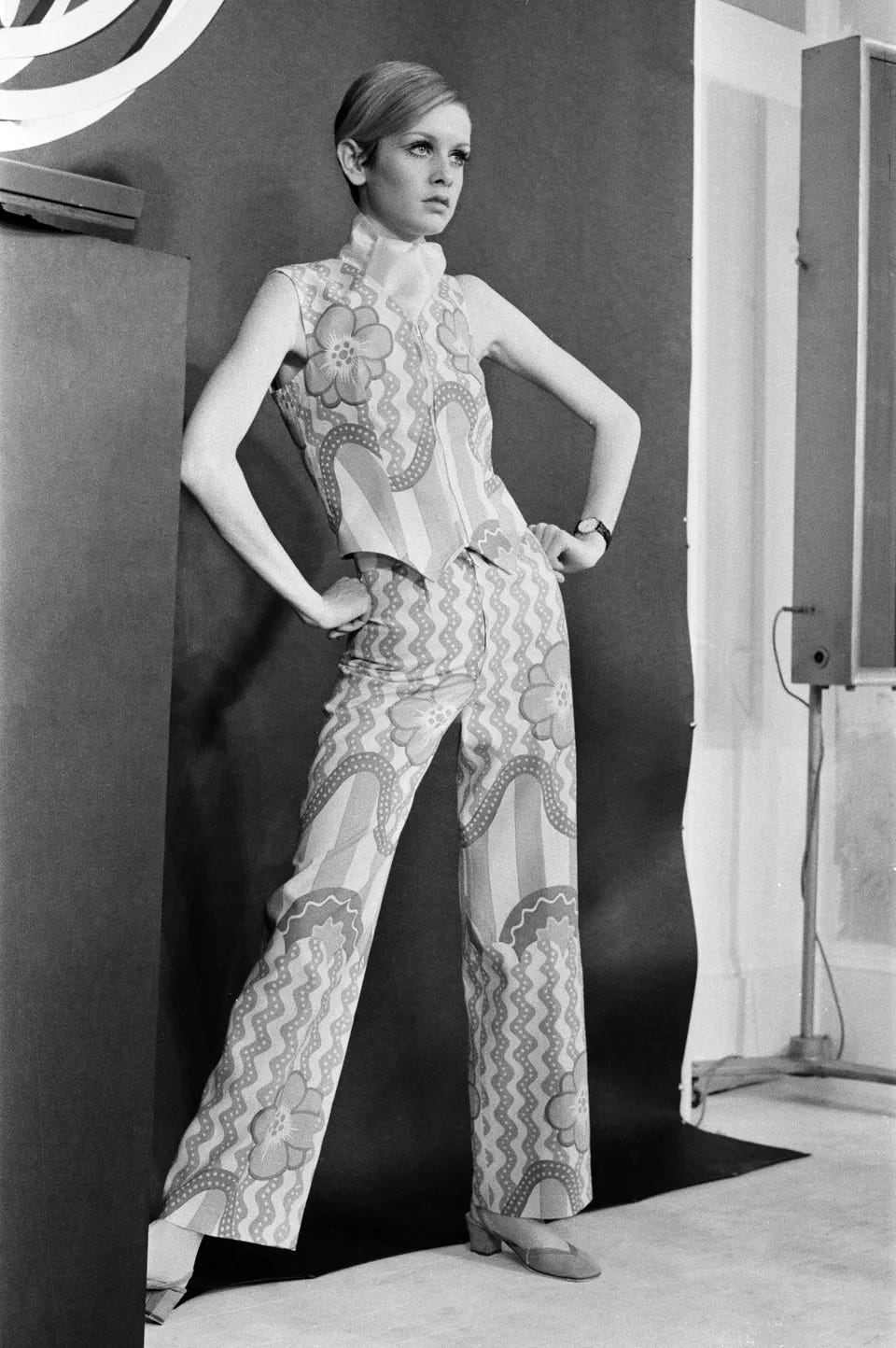

Sun-Times: A spot of tea with Twiggy

Daily News: The new Twiggy: that boyish kid is all grown up

Twiggy, the ‘60s super model who more than anyone else made it cool and thus necessary to be so thin that people should worry you have a terminal illness, is back in Chicago for the first time in four years. The Trib passed on her, for some reason, so no companion piece from them.

The Daily News’ unsigned piece proclaims in its lede, “The Twig is blossoming. She’s even wearing a bra.” Which the paper helpfully put on its front page today, right next to the headline about Dick Allen.

Barbara Varro of the Sun-Times has tea with Twiggy in her suite at the Continental Plaza. When asked if she still weighs 92 pounds, Twiggy laughed and jumped up: “Look, I’m a fatty now. I weigh between 96 and 100.” She is 22, and has put modeling behind her for movies.

Twiggy is here promoting her first film, “The Boy Friend,” directed and produced by Ken Russell, which opens here in January. It’s based on a 1950 stage production starring Julie Andrews. So this is a musical requiring real singing and dancing. Twiggy took six months of lessons to catch up to Julie Andrews. Sure.

The Daily News reminds us that Twiggy is a global household word, who’d once said she made enough money to retire before age 20. “Her top fee was $22,000 for a three-day shooting, or $1,000 an hour for a couple of shots that took less than half a morning.”

December 3, 1971

Tribune: “Allen-Melton New Murderer’s Row?

By Richard Dozer

Sun-Times: Sox get Rich Allen, Bahnsen

By Jerome Holtzman

Chicago’s morning papers finally get their chance to report on the epic trade that brought Dick Allen to the White Sox.

Yesterday, the Daily News shouted the news in a giant above-the-masthead front page headline with an exclamation mark—Pearl Harbor level coverage. Today, the Trib and Sun-Times are surprisingly calm.

“The Chicago White Sox landed Richie Allen plus the first six-figure salary in the club’s history all in the same deal today” led the Trib’s Dozer, leaving the size of the biggest paycheck in Sox history for close to the end--$110,000.

The Sun-Times runs a weirdly boring headline only on the Sports page: “Sox get Rich Allen, Bahnsen.”

Jerome Holtzman’s story doesn’t muster much more excitement: “Chicago’s White Sox swung into action Thursday and definitely strengthened themselves with the acquisition of Richie Allen, a controversial home run slugger, and starring pitcher Stan Bahnsen.”

“The 29-year-old Allen…should add considerable power to the White Sox lineup,” Holtzman adds almost with a yawn. “He has a career total of 234 home runs and has had four seasons in which he has hit 32 or more.”

But Holtzman does use the most upbeat quotes from manager Chuck Tanner: “We’ve got a guy who can win as many as 20 games for us with his bat,” he said. “I consider Allen a superstar.”

Yesterday the Daily News ran an entire separate article on Dick Allen’s controversial history, which Dick Allen fans know is quite complex. Today, the Trib and Sun-Times surprise by gliding over it quickly.

The Trib says Tanner “was bombarded” first at the press conference “about questions of how he plans to handle Allen.” Tanner, whose hometown is only 20 minutes from Allen’s in Wampum, PA, and who knows Allen, says “I know one thing. He gives 100 percent on the ballfield. I’ll judge Richie Allen on what he does for me—and only that.”

Dozer sums up the issue in a sentence, writing that Allen’s “troubles” in Philadelphia “traced to arguments with ownership and on occasion with fellow players.” He adds: “Al Campanis, Dodger general manager, said Allen had not given Manager Walt Alston the slightest trouble last season.”

Dozer notes that Allen batted .295 with 90 runs and 23 homers last year. “The latter production was less than his usual total, but Dodger Stadium is regarded as a difficult power park,” he writes. Tanner says Allen will “hit well in our park. We just could have the best 1-2 sluggers in the American League between him and Bill Melton.”

The trading session, recall, is going on in P.K. Wrigley’s Arizona Biltmore Hotel. Dozer writes that “Reggie Jackson strolled into the Arizona Biltmore lobby looking for his boss, owner Charley Finley of the A’s, soon after the deals that brought Richie Allen to the White Sox.” Jackson says “it’s the White Sox who made themselves the best deal of the week, getting Richie [Allen].”

There is a hint of possible drama to come, though, thrown in nonchalantly toward the end of a Trib’s longer article on the overall day’s major league trades: “The White Sox were having trouble locating Allen after today’s trade, but Manager Chuck Tanner said he talked with Rich’s mother in Wampum, Pa., which is the Allen home. Rich reportedly is in Los Angeles. There was no answer at his home.”

“His mother told me she was very pleased at the trade,” said Tanner. We’ll hear more on this from Defender sports columnist A.S. “Doc” Young.

December 4, 1971

Chicago Daily News, Lu Palmer column: Hanrahan, Hampton 2 years later

“Two years ago, on Dec 4, 1969, police from the Cook County state’s attorney’s office raided an apartment in Chicago’s West Side ghetto,” writes veteran journalist Lu Palmer, who will leave reporting and become a legendary Black Chicago political activist and organizer.

“What happened was immediately flashed across the nation as a police ‘shoot-out’ with members of the Illinois Black Panther Party, writes Palmer. “Four Panthers were wounded and two were killed. Chairman Fred Hampton and Peoria Panther leader Mark Clark lost their lives in what a federal grand jury later showed to be a ‘shoot-in.’”

Now, Cook County State’s Attorney Ed Hanrahan and 13 others are indicted for obstructing that grand jury investigation. “The major difference between Hampton and Hanrahan is that Chairman Fred is dead. Hanrahan is not only alive but is looking forward to being re-elected.”

[See the November 8-14 weekly compilation of This Crazy Day In 1972 for more background under November 12—”Hanrahan attacks indictments again” and “Hanrahan asks place on ticket.”]

Many Black Chicagoans believe Hampton was murdered, writes Palmer. FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover calls the Black Panthers “the No. 1 threat to the nation.” When Hampton spoke before his own death at a memorial for two brothers killed in separate police incidents, Palmer recounts, Hampton said: “’I often wonder what I would be, if I had been born free.’”

“One thing Chairman Fred—and many other blacks like him—would be if they had been born free is alive,” writes Palmer. “Hanrahan is alive and is concerned only about his political life. But he has little reason to worry. He is the protégé of Mayor Richard J. Daley…he is still in office. Few people believe he will be dumped by Daley, and if he is it will only be because Daley figures him to be deadweight.”

Hanrahan is currently trying to get his indictment thrown out of court. Palmer writes that Hanrahan claims the grand jury didn’t charge him with any crime. “And so he asks, ‘Conspiracy to obstruct the prosecution of what?’” writes Palmer.

“It’s a one word answer and it tells a world. The word is murder.”

December 4, 1971

Chicago Daily News: Wife-beating ban

UPI

“The Rhode Island Supreme Court ruled Friday that men do not have the right to beat their wives.”

The court ruled again Cranston, RI lawyer Aram K. Berberian, “who said the state and federal constitutions guaranteed his right to assault his wife ‘in accord with his fundamental right to chastise her.’”

December 5, 1971

Chicago Tribune, Vernon Jarrett column: The Odds Against A Top Black Boss

Today Dick Allen, the newest White Sox star for just three days now, is brought together with the ongoing totally confusing crisis at Cook County Hospital by Vernon Jarrett, the Tribune’s first Black columnist, who started at the paper in 1970. Some background:

The Cook County Hospital crisis is so convoluted I have no idea what’s going on—and neither does anyone else. Hundreds of doctors threatened to quit over policies of Hospital head Dr. James G. Haughton. The executive committee of the medical staff called for Haughton’s resignation. Haughton dropped that post but kept his main job as executive director of the entire health system.

Haughton fired five doctors he claimed had threatened to shut down the hospital. A judge reinstated the doctors and ordered a special committee to figure it out. Everyone seems to think Haughton wants to change Cook County Hospital from a teaching hospital to a small community hospital, but Haughton absolutely denies that.

What are they really fighting about? Part of it is definitely whether Medicare and third-party payments will go directly to the hospital rather than the doctors, who say that money goes to a nonprofit group and spent on hospital improvements and professional services.

On November 11, Mike Royko wrote a column that began, “According to my calculations, the current County Hospital crisis is the tenth crisis in the past 10 years…This one I find to be the most confusing. The others were relatively simple…But nobody except the people involved seem to understand what this one is all about, and I’m not sure if they do.”

On November 26, the Tribune wrote an editorial titled “What Future for County?” admitting they don’t know what’s going on, concluding: “The Tribune would like to see Dr. Haughton and serious critics of his policies seek first a private accommodation and then, if their search does not succeed, a public airing of their differences.”

Today, Vernon Jarrett tells us via a loquacious local sage in a South Side bar that this whole thing is because Haughton is Black, and white folks aren’t used to having a Black boss yet. But even Jarrett may not be sure about that. Jarrett gives us no background on the crisis events, and he includes one voice who says Haughton can be wrong even though he’s Black.

Jarrett’s lede: “’Hey, have you seen the newspapers?’ a pudgy black man asked the bartender as he approached his usual position at the bar in a South Side tavern that serves as a debating society for a group of evening regulars.”

The unnamed sage says he should have taken an offered bet the first time Dr. Haughton arrived on Chicago television. “I’m talking about the big one we had that night the first time we saw the new boss of Cook County Hospital on television. The black guy they fighting over right now…

‘When I saw him sitting there all businesslike, all proud acting and firm and straight and talking like he really thought he was in charge, I told all of ya that Chicago ain’t ready for a real black man.’ ‘Not in charge of white folks,’ a tenor voice chimed in.”

The “lecturer,” as Jarrett now calls the main sage, says the current situation is like when Branch Rickey hired Jackie Robinson as the first Black major league baseball player for the Dodgers, and told Robinson he’d need to ignore racial taunts and other reasons to fight.

“But let me tell you where you wrong,” says one patron called “Boston.” “’Black baseball players are just as odd as the white ones. Look at Richie Allen.’ ‘But what you don’t understand,’ the lecturer answered, ‘is people are now used to black baseball players. What you don’t understand is that any job you take that’s different—well white people have to get used to seeing you there before you can act like them.’”

“’Not only that, added the bartender, ‘he’s [Dr. Haughton] the second or third highest paid public official in Illinois—60 grand, baby.’”

“’But just ‘cause he’s black don’t mean that he can’t be wrong,’ cautioned another voice,”-- perhaps in this context Jarrett’s? --“’He can be corrected.’”

The tenor voice concludes the discussion: “’Hey don’t worry about a thing, Haughty,’ supported the tenor voice. ‘Just do you thing and do it right, and go on with you old proud West Indian self.’”

Vernon Jarrett, FYR, was one of the most distinguished Black journalists of his generation. He came to Chicago in 1946 as part of the Second Great Migration of African-Americans out of the South and started at the Chicago Defender. Jarrett moved into broadcasting by the end of the decade, producing “Negro Newsfront,” the first daily Black news show, and later hosting a Sunday talk show on Chicago’s Ch. 7, WLS. Jarrett became the first Black columnist at the Tribune in 1970—which became nationally syndicated. He moved on to the Sun-Times 1983-1994.

Like contemporary Lu Palmer, Jarrett was also an activist who saw himself in the tradition of Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells-Barnett. He was an early mover in Harold Washington’s mayoral campaign, helped found the National Association of Black Journalists, and he founded the NAACP’s ACT-SO program—Academic, Cultural, Technological and Scientific Olympics, which still awards thousands of dollars yearly in college scholarships. Vernon Jarrett died in Chicago in 2004.

December 5, 1971

Chicago Tribune, Jim Murray column

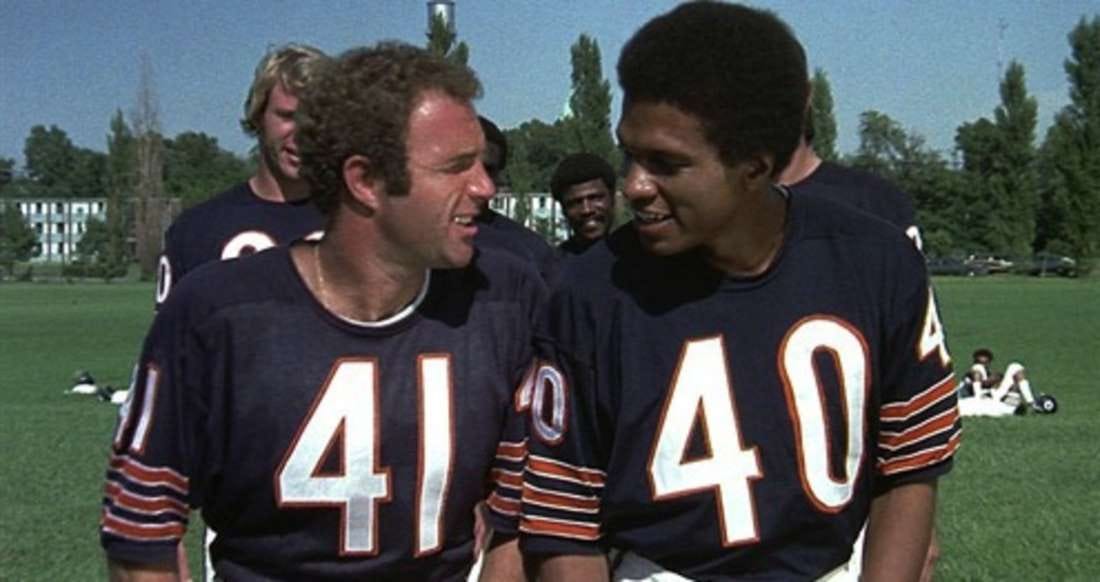

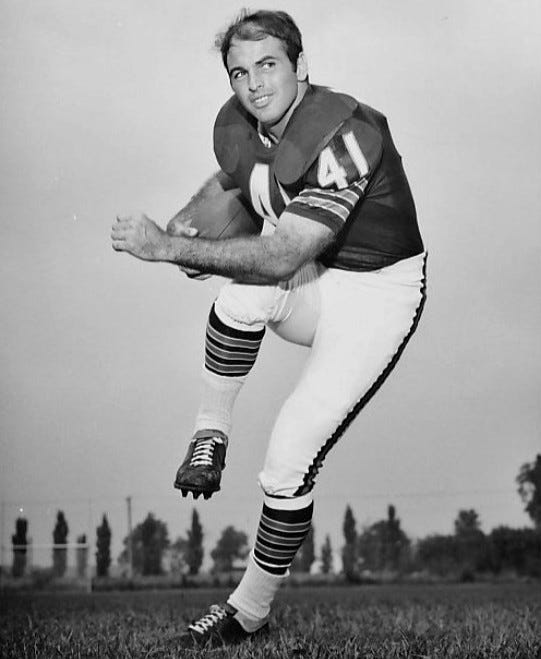

A seminal event in Steve Bertolucci’s 10-year-old life happened this past Tuesday, November 30: ABC aired the made-for-TV movie “Brian’s Song,” about the deep friendship between Bears star Gale Sayers and his teammate, Brian Piccolo, who died of cancer in 1970—based on Sayers’ autobiography, “I Am Third.”

The blockbuster movie, so popular that it came back for an unprecedented theater run after playing on TV, starred Billy Dee Williams as Gale Sayers and James Caan as Brian Piccolo. Their performances were so iconic, many if not most Americans remember both football players now while picturing those two actors.

Steve and his five brothers spent much of the movie in front of their black-and-white TV in the front room of their bungalow at 12426 S. Wabash trying not to cry in front of each other. It was not an unusual situation, as we glean today from Trib sports columnist Jim Murray.

“The kind of a guy Brian Piccolo was, facing the Minnesota Viking front four was like playing schoolyard tag,” writes Murray. “The real Purple People Eater was in his chest. He tried to run on it to the last. He met it at the line scrimmage. He was still trying to straight-arm it when the whistle blew. It was the fourth down and a hundred to go but Piccolo was still calling for the ball.”

“Tuesday night on ABC you saw the biggest [game] any football player ever had to play. It didn’t have color by Howard Cosell. It was N.F.L. Highlights of a sort. It was also a love story. ‘Brian’s Song’ was a telemovie of extraordinary poignance and importance in this day when the rhetoric of hate is otherwise drowning out the microwaves. I hope it gets a bigger rating than the Super Bowl. It’s for sure it’ll be remembered a lot longer.”

“What do you say about a 26-year-old football player who died?…He was a one-man Brotherhood Week 52 weeks a year…He ran it out all the way. He never ran out the clock in life. He was still trying for a first down when he died.”

Piccolo wasn’t big, and he was really just Sayers’ back up when the true star needed a rest. But Piccolo didn’t mind that. Chicago writer Jeanne Morris’s recent book on Piccolo, “The Short Season,” describes how Piccolo was devoted to his wife, but spent “equal time and devotion on his sister, Carol a young lady afflicted with cerebral palsy. Pick carried her out of church, swam with her, joked with her, was as attentive as he was to Joy.”

“…one of the Bears said you could get two season tickets free if you ever found a picture where Pick wasn’t smiling.” Piccolo told his own wife not to cry during his illness. “It’s a league rule,” he said.

“He was not around to enforce the league rule in your living room last week,” writes Murray.

Do you dig spending some time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the book being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.