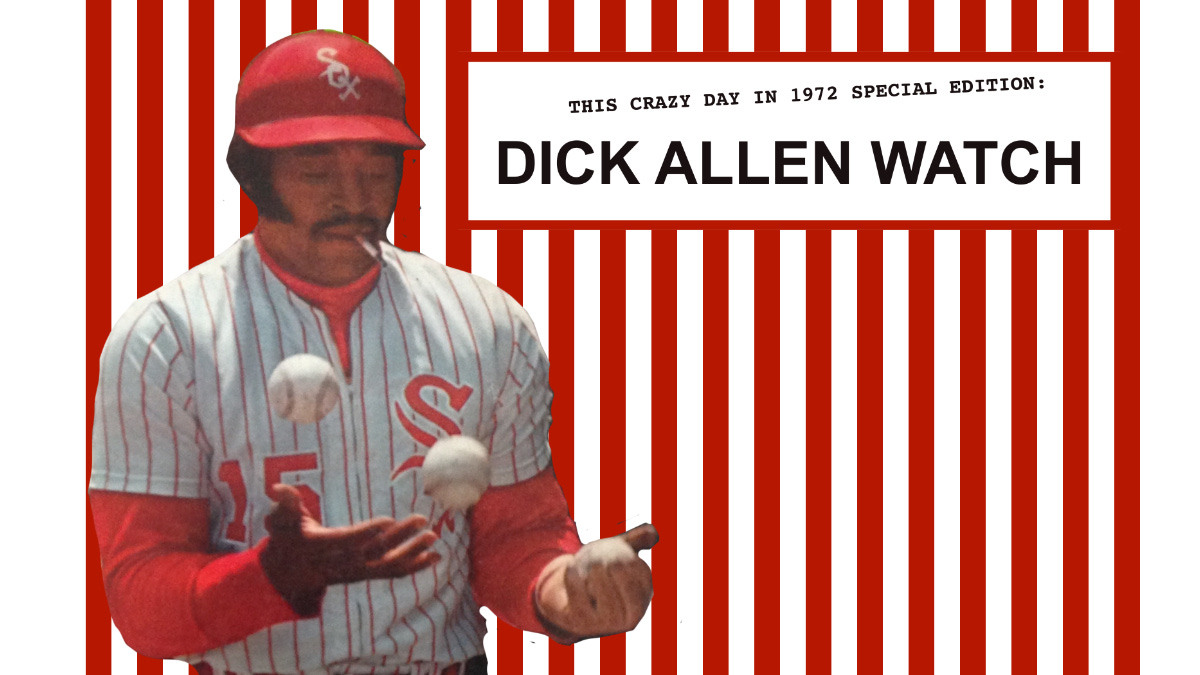

THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972: The bank time bomber revealed!

Weekly Compilation January 10-16, 1972

To access all contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 was part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. If you’d like, keep up with the 1972 papers every day on Twitter, @RoselandChi1972.

January 10

Chicago Daily News, front page: Cubs sign Jenkins for $125,000!

No byline

Tribune: Highest Paid Chicago Pro? Jenkins Signs for 2 Years, $250,000

By Richard Dozer

“Ferguson Jenkins signed a two-year Cub contract Monday that makes him the highest-paid player in Chicago baseball history,” the News exclaims on the front page. Fergie is “a 20-game winner in each of the past five seasons”.

Fergie also won the Cy Young award last year for his 24-13 record. Fergie and Cub VP John Holland held a Wrigley Field press conference to announce the contract but then “would only say the figure was in excess of $100,000. But the contract terms for the 28-year-old Canadian righthander were learned from other sources.”

Cubs owner P.K. Wrigley has a “policy of secrecy on salary terms,” but they announced Billy Williams’ $100,000 contract last year.

The White Sox have offered “newly-acquired slugger Richie Allen $110,000, and Allen may push that figure up in negotiations.”

Technically, the Tribune covers this on January 11, but we’ll break with protocol and quote the Trib’s account today. The Trib’s Dozer called it a “hastily drawn press conference” where “Terms of the contract were not divulged beyond an understatement by the Cubs that Jenkins will receive ‘in excess of $100,000 per year”.

But “an impeccable source” put the number at $125,000, “which makes Fergie the highest paid baseball player in history.

“Some speculate that Jenkins may be the highest-paid athlete of any sort among Chicago’s varied sports franchises, although Bobby Hull, whose Black Hawks contact certainly is in six figures as well, likely is in the same range with equally mysterious wage arrangement.”

“Last year was the first time in several seasons that I felt strong at the end,” Fergie said. At the. Press conference. “I’m sure Leo [Manager Durocher] wants to start me every fourth day, and that’s what I want to do…Otherwise, I haven’t set any goals for myself, but Billy [Williams] and I probably will sit down and do that sometime before the season begins.”

Fergie attended the press conference with a “phalanx” of Canadian aides headed by attorney Dave Schatia, who said the National Film Board of Canada was financing a film about Fergie shot over the coming year, and “Two books will be written on Jenkins within the next year, too.”

January 10

Chicago Daily News: Smoky room called threat to nonsmoker

By Robert Gruenberg

Who knew?? Who could possibly predict that a daily habit that leaves its adherents hacking first thing in the morning and fills their homes and offices and cars with the same noxious substance that has already been determined causes cancer, could be a problem for everybody else?

“Nonsmokers may suffer serious health injury—especially if they have lung and heart disease—merely from being in the same room or car with smokers". That's the major finding in “The Health Consequences of Smoking”—the sixth smoking study by the U.S. Public Health Service.

“Carbon monoxide, a deadly gas, is an important part of tobacco smoke and, when combined with oxygen-carrying elements of the blood can be seriously harmful,” the report says. It supports the 1964 report that concluded “’cigarets are a major cause of death and disease,’ said Dr. Jesse L. Steineld, PHS surgeon general.”

Steinfeld says 29 million Americans have quit smoking since that 1964 report, though he “conceded” that 44 million Americans did not quit.

January 10

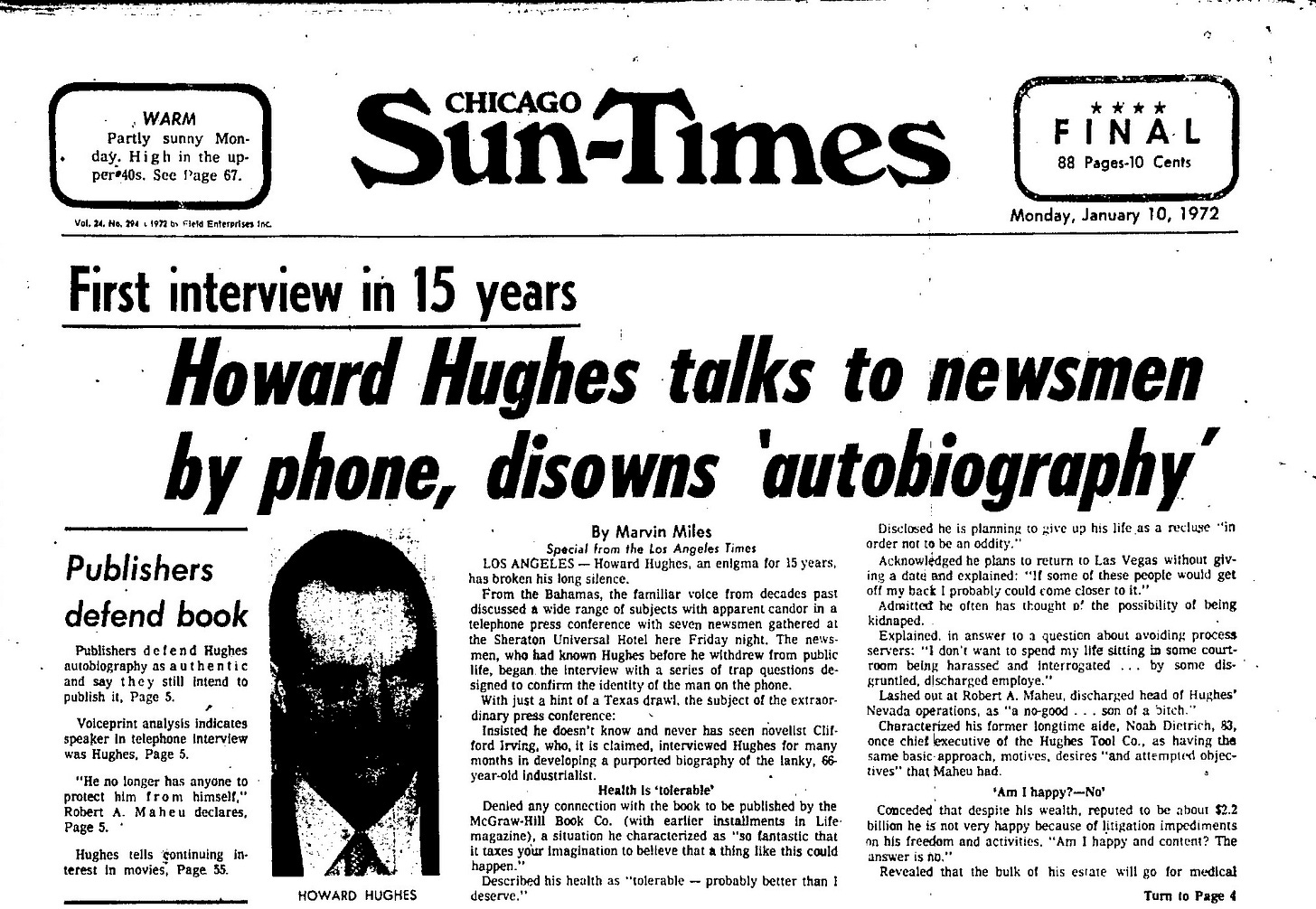

Chicago Sun-Times: Howard Hughes talks to newsmen by phone, disowns ‘autobiography”

By Marvin Miles, LA times

“Howard Hughes, an enigma for 15 years, has broken his long silence.”

FYR, Howard Hughes was THE eccentric billionaire of the 20th century. The Leonardo DiCaprio movie will catch you up nicely— “The Aviator.” You have to give it to Hughes: He really did design and fly experimental planes. Imagine if Elon Musk designed one of his rockets himself, and then was the first to fly it.

“From the Bahamas, the familiar voice from decades past discussed a wide range of subjects with apparent candor in a telephone press conference with seven newsmen gathered at the Sheraton Universal Hotel here Friday night.”

The reporters on this telephone press conference all knew Hughes before he disappeared from public view. They started by asking “a series of trap questions designed to confirm the identity of the man on the phone.” Remember, this is before Zoom!

Hughes spoke with “just a hint of a Texas drawl” and insisted “he doesn’t know and never has seen novelist Clifford Irving, who, it is claimed, interviewed Hughes for many months in developing a purported biography of the lanky, 66-year old industrialist.”

The book portrays Hughes as JPN—Just Plain Nuts, with finger and toe nails nine inches long. Americans have feasted on the crazy Howard Hughes anecdotes from excerpts in Life magazine.

McGraw-Hill and Life say they have the true Howard Hughes autobiography—and they’ll publish it in spring no matter what Hughes says. They claim to have a 10-page hand-written letter from Hughes, and that they paid him checks which he’s endorsed and cashed.

Hughes says the situation is “so fantastic that it taxes your imagination to believe that a thing like this could happen.”

Hughes says he’ll come back to Las Vegas from the Bahamas and stop being a hermit “in order not to be an oddity.” Hughes gave his last interview in 1957, and refused to testify in a 1961 lawsuit against him by Trans World Airlines, resulting in a $137 million default judgement against him.

Hughes “conceded that despite his wealth, reputed to be about $2.2 billion, he is not very happy because of litigation impediments on his freedom and activities.”

Hughes: “Am I happy and content? The answer is no.”

January 10

Chicago Sun-Times: Dunne pledges to slash 18 useless county jobs

By Thomas J. Moore

A Sun-Times-BGA investigation found traffic accident investigators for the Cook County Traffic Commission were doing a job that could be replaced by just having somebody mail accident reports to the Commission from suburban police departments.

Plus, four of them were ghost payrollers anyway.

Cook County Board President George Dunne says the County has investigated, and “The results of our study shows the same things that yours did.” So he’ll fire them all. You’ve gotta hand it to George Dunne—he can say these things with a straight face.

BGA head Terrence Brunner says a new BGA investigation also found the County Rabies Department budget grew from $94,000 to $351,000 over the last ten years even though the last dog with rabies was reported in 1954. Brunner “called for the abolition of that agency.”

Dunne said, “Just because there have been few cases of rabies, that doesn’t mean the surveillance should be discontinued. It means the department is effective.”

“When Brunner was asked at a Sunday press conference…if he thought the county’s 15 commissioners were aware of the waste, he said, ‘I don’t see how they could miss it. Just look at their new County Board room. The $20,000-a-year commissioners sit down in $236 red velvet chairs for their meetings. They put their cigarette ashes in $18.60 ashtrays and perhaps drop their cigarette wrappers into their $23 tortoise-shell leather waste-baskets with antique brass trim.”

“The County Board room was remodeled last year at a cost of $58,607, Brunner said. The redecorating job included solid walnut paneling and desks, red velvet drapes at $10.40 a yard and plush blue and yellow carpeting.”

Dunne on the remodeling: “They can talk all they want about the cost of a desk, but I don’t think there was anything that was excessive. Everything was taken at competitive bidding.”

Fun fact, long time BGA head Terry Brunner bore an uncanny resemblance to Johnny Carson. I wonder if he still does?

January 11

Chicago Daily News: Court row flares over temporary patronage

By Ed Kandlik

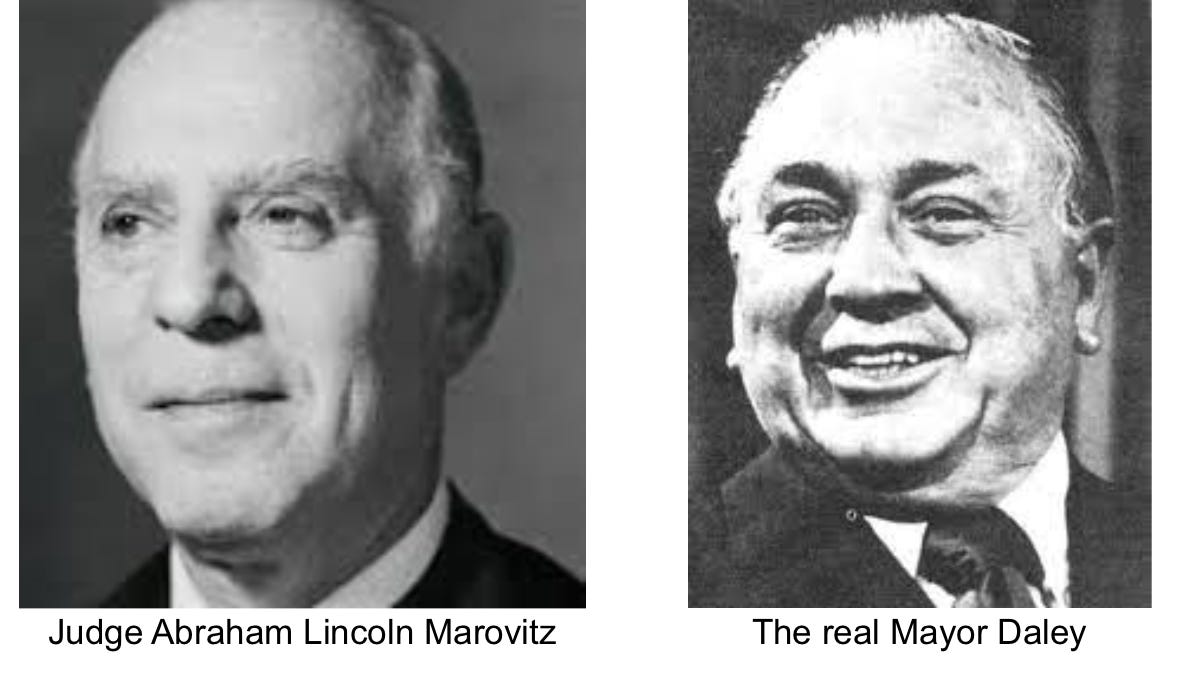

The Shakman Decree case seeking to limit Mayor Daley’s Democratic Machine patronage workers continues in front of Judge Abraham Lincoln Marovitz, Mayor Daley’s close personal friend. You read that right, Younger Readers.

Mike Royko on Marovitz & Daley in "Boss": "With the Hatch Act forbidding federal judges to do any politicking, what other judge spends every election night in the charmed inner office of Democratic Headquarters, sitting with Daley as the returns come in? That's friendship."

The Shakman Decree is named for attorney Michael Shakman, chairman of the Independent Voters of Illinois (IVI) in 1972. Judge Marovitz originally dismissed Shakman’s lawsuit, but the U.S. Supreme Court said not so fast. Shakman’s attorney negotiated the Decree with Democrats and Republicans to end firing or disciplining patronage workers who don’t do political work. But they’re still haggling over the details before officially signing off, scheduled for February 14.

Today, Republican Illinois Governor Ogilvie’s assistant attorney general Robert Tingler wants Judge Marovitz to strengthen the decree by eliminating “temporary” patronage jobs, which are summoned out of thin air to get around civil service requirements.

“We think the government should serve all the citizens and not just serve to produce Democratic machine puppets,” Tingler told Marovitz, Mayor Daley’s personal friend. “Ogilvie has estimated that the Daley organization has created about 11,000 temporary patronage jobs,” writes Daily News reporter Ed Kandlik.

Peter Fitzpatrick, representing the Democrats, jumped up and yelled, “I object!”

“Marovitz, a Democrat and close friend of Daley, sternly admonished Tingler,” writes Kandlik. “’Don’t use this courtroom for political speech,’Marovitz said. ‘Whatever you say about the Democratic Party is applicable to the Republicans. You can take your publicity releases outside this courtroom.’”

Shakman originally wanted the entire patronage system eliminated. The ACLU, which represented him, says it will probably file a new suit to try that again.

January 12

Chicago Daily News: Uniforms stolen

UPI

(DUBLIN)—A spokesman for the IRA said the organization has stolen 200 British army uniforms from a Londderry dry cleaners.

January 12

Chicago Daily News: New ‘lib’ group is tax-exempt

AP

“Gloria Steinem announced Wednesday formation of the Women’s Action Alliance, a tax-exempt organization designed ‘to assist women working on practical, local action projects.’”

Steinem said the alliance “is a natural result of the success of the women’s movement to date”. The women’s Action Alliance will “offer research and technical assistance to local groups, serve as a referral and information service, and serve as a communications center between local action groups.”

January 12

Chicago Daily News: ‘Evidence’ of mass forgery on Berg petitions filed by IVI

By Edmund J. Rooney

The saga of the obviously forged nominating petitions for Mayor Daley’s candidate for state’s attorney, Traffic Court Judge Raymond Berg, keeps going and going.

Mike Royko broke the story that when Daley dumped indicted state’s attorney Ed Hanrahan from the Democratic ticket for Judge Berg on the very day petitions were due to get on the ballot, Machine flunkies spent the day forging 20,000 signatures.

The IVI sued Daley and the Board of Election Commissioners in federal court to get voter records to compare signatures with the petitions. But the Election Board took so long to get voter records, the IVI couldn’t analyze them in time for its hearing before the entity that hears challenges to nominating petitions, the County Electoral Board. The Electoral Board refused to give the IVI an extension and threw the case out. See Mike’s January 6 column, “Why they OKd the petitions” for a fun Q & A on that fiasco.

Today the IVI is back in federal court with U.S. District Court Judge Thomas McMillen, trying to force the Electoral Board to reopen the case. They filed evidence today proving, among other things, that two signatures are definitely from dead people, there are signatures from people who say they didn’t sign, and petition circulator signatures from people who did not circulate petitions.

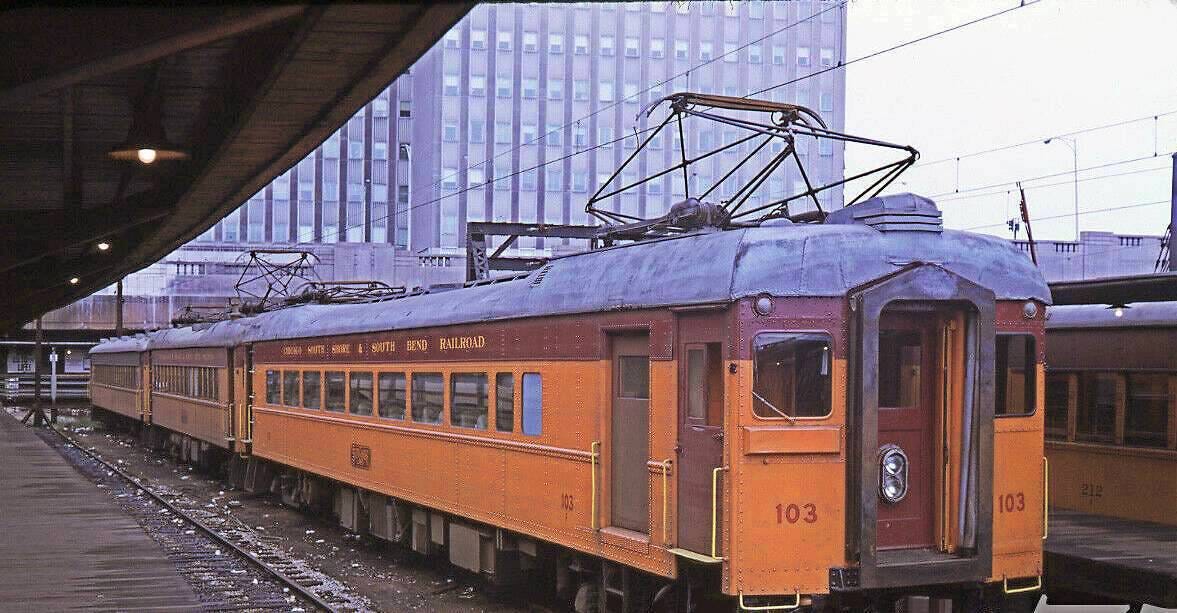

January 12, 1972: The Mighty IC #1

Chicago Daily News & Chicago Tribune

The Illinois Central Railroad’s commuter train had 18 serious delays in the last four months of 1971 alone, which brought the Illinois Commerce Commission sniffing around to see what’s up. ICC examiner Joseph McHugh came to Chicago to hold an investigatory hearing.

The Tribune’s David Gilbert reports that IC attorney Howard Koontz blamed the avalanche of delays on the IC’s new double decker train cars. The IC is slowly introducing the new double deckers, replacing their ancient single-story cars.

The double-decker cars are bigger and use more electricity, it turns out. Koontz asked the ICC “to order Commonwealth Edison Co, which supplies electricity to the I.C., to testify in a future hearing about the capability of Edison to meet increased electrical demands”.

But the Daily News’ Betty Washington reports further: IC power supervisor Everett E. Ellsworth testified that six of the 18 delays were caused by Edison’s substation near Flossmoor. “However, Ellsworth said there have been ‘other instances where power was available but because of some defect in the commuter cars or other facilities, power could not be used to operate the trains.”

In other words, 12 of the 18 delays can’t be blamed on Commonwealth Edison.

McHugh says he’ll have to investigate further to understand the true source of all the power failures. Adjourned until February.

“State Rep. Robert Mann (D-Chicago) and Rep. Bernard Epton (R-Chicago) testified that the delays continually inconvenience commuters.” For Older Readers: Yes, that Bernard Epton.

Why do we care about the IC? Since this is the first IC story of 1972, we’ll provide that background here. If you already read about the IC in Chapter 2 Notes Part 3, or you’re not interested, click here to scroll to the next story.

The Mighty IC: Even a train has to start somewhere

The Illinois Central Railroad literally runs right through the beating downtown heart of Chicago—and the South Side.

At “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” we care about the IC because the hero of the book at the center of this Substack, Steve Bertolucci, grew up riding the IC downtown from Roseland. As an adult, he takes the IC from Hyde Park to his office at Rose & Rose on the 13th floor of the IBM Building.

But there’s a lot more to the IC than the commuter line serving the South Side and south suburbs. It’s actually an integral part of Chicago history. Pull up a chair, if you have time.

As a kid, Steve took the IC with his family to see Marshall Field’s Christmas windows, and he took the IC with his rebellious Nona in 1972 on a secret journey to see “The Godfather.” Steve’s mom said he was too young, but Nona wanted company, and she wasn’t waiting months until the blockbuster film finally moved on from the Chicago Theater and filtered out to smaller neighborhood theaters—for that is how movies worked in 1972.

Back then, the seats were wicker and destroyed all the women’s nylons. And the women were all wearing nylons in 1972. The single-story train cars were nearly 50 years, ancient and delapidated. The IC was slowly adding the first shiny new double-decker orange-and-silver train cars of a fleet ordered from the manufacturer in 1969.

The IC’s main line runs on an embankment above the South Side neighborhoods it serves, always getting closer to the lake as it approaches downtown. Grown-up Steve gets on the IC at 53rd Street. The first good glimpse of the lake comes right here, but you have to look quickly as the train rumbles over the 53rd Street viaduct. After 47th, the buildings lining the track’s east side stop abruptly. Now the train runs just west of Lake Shore Drive all the way to 12th Street, where it reaches the southern end of Grant Park, often called “Chicago’s front yard.”

Here the IC tracks begin rushing through the city’s front yard like a river in a railroad canyon. The railroad canyon is soon one level below grade, with stone walls just like the real thing. Here’s a slightly newer view than the Mighty IC logo above, though this one is also before 1976, since the Art Institute’s 1976 addition isn’t there yet:

North of the Art Institute—after the foreground of this photo ends—the tracks used to pass a giant parking lot to the east, then disappear entirely underground by the time they reached Randolph. Now the tracks disappear sooner, hidden by subterranean parking garages and Millennial Park.

Here’s another postcard from John Chuckman, shot from the east overlooking the old vast parking lot. It’s like an asphalt Great Plains. You can see the Wrigley Building peeking in on the right side in the distance.

Steve gets off the IC at the end of the line, at the main station underground at Randolph and Michigan. It’s nothing special and never was. Steve and his fellow IC commuters herd themselves like intelligent cattle through the Randolph station’s corridors, so reminiscent of Stockyard chutes with the low ceilings and stuffy old air. Finally they swell up the stairs that deposit them next to the broad stone steps of the old library’s front entrance. Then Steve and his fellows all blink in the sudden sun. Their first glimpse of the Loop always radiates from that southwest corner of Randolph and Michigan.

The IC commuter train line is now part of the regional Metra train system, so Steve is really arriving downtown at the Randolph Street Metra station, which isn’t even the Randolph station anymore. It was renamed for Millenium Park after Chicago spent hundreds of millions of dollars to turn the northwest corner of Grant Park into a tourist Disneyland at the turn of the 21st century.

To anyone who grew up taking the IC back in the day, it’s still the IC, and still the Randolph station—or just “Randolph.” People who call this train line “Metra” give away their relative newcomer status. People who call it “the IC” give away their old-timer status. Which status is preferential depends on your perspective. Neither should be preferential, but we all know everybody has a preference.

The IC in the Wayback Machine

Most people remember, in a general way, that Chicago beat out other Midwestern cities like St. Louis to become the country’s central hub for transportation and, thus, trade. But that didn’t happen automatically just because Chicago sits on the shores of Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Chicago River.

As Donald L. Miller puts it in his epic book City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America, “Nature hadn’t created Chicago….she had merely made it possible. The city would not have been set on its course had not men of energy and empire first envisioned and then cut a canal”—the Illinois and Michigan Canal.

The I&M Canal opened in 1848, linking the south branch of the Chicago River to the Illinois River, running from Bridgeport to LaSalle-Peru. This 96-mile long, 60-foot wide artificial river, dug by Irish immigrants over the course of a dozen backbreaking years, connected Chicago by water for the first time with the Mississippi.

Suddenly, ships could travel from New York to the Gulf of Mexico—via the Erie Canal to the Great Lakes, on to Chicago, then through the I&M Canal to the Illinois River and finally the Mississippi.

That was Chicago’s first punch, a hefty left jab at all its Midwest rivals. The knock-out came chugging along railroad tracks.

“It was water, ironically, that guaranteed Chicago’s place as the nation’s railroad hub,” Miller explains. “With the completion of the Erie Canal and the Illinois and Michigan Canal, Chicago’s location as the terminus of an all-water route between New York and the Gulf of Mexico, the longest inland waterway in the world, made it virtually certain the city would become a major rail center.”

And it happened fast.

“By 1857, Chicago was the center of the largest railroad network in the world, consisting of three thousand miles of track,” writes Miller. “Almost a hundred trains entered and left the city every day, and everywhere its trains went, they changed frontier into hinterland and brought to the city the multiplying products of farms and forests.”

Chicago’s first railroad was the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad, starting operation in 1848. But, writes Miller, “The railroad that had the earliest and longest-lasting effect on Chicago’s physical environment was the formidable Illinois Central.”

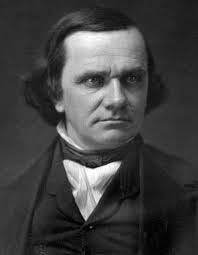

Even back then, Chicago became Chicago through clout. In 1846, Illinois’ newly-minted U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas went to Washington determined to pass the necessary federal legislation for an Illinois Central Railroad, running the full length of the state and down to the Gulf of Mexico. Douglas succeeded—and after moving to Chicago in 1847, he amended the IC plan to include a branch to his new hometown. Then Douglas bought a lot of the land that now makes up the near South Side, which an IC Chicago branch would need. Douglas simultaneously made a nice profit selling the railroad the land it needed, and made his remaining holdings more valuable as part of the IC route.

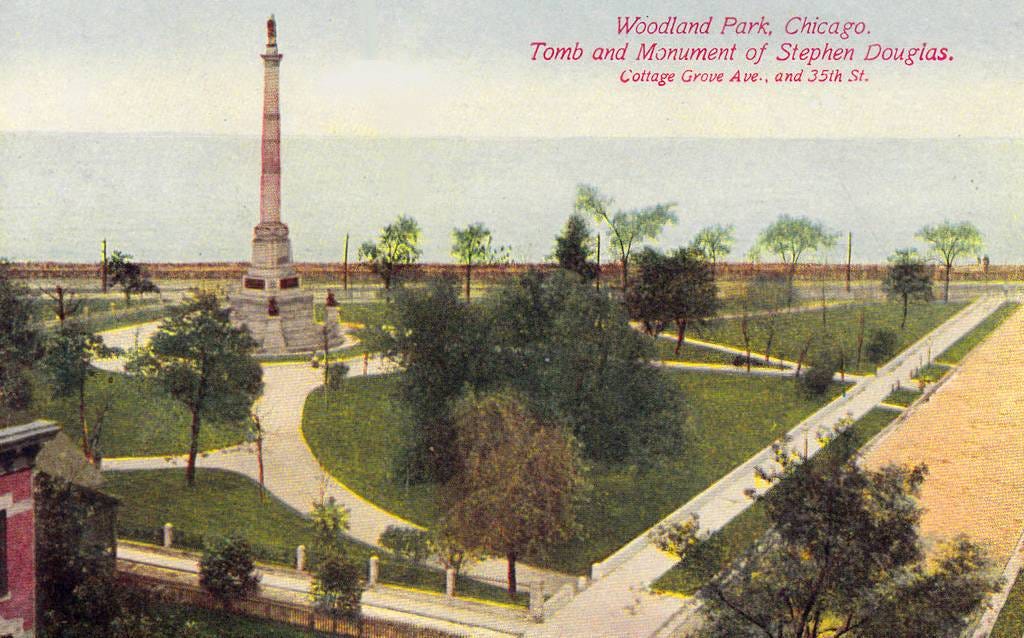

You can still see Stephen Douglas from the IC as it passes 35th Street, on the west side of the tracks. Sort of. You’re looking at a ten-foot high statue of Douglas, dwarfed by its 40-foot marble column. This seems almost a purposeful irony, since the diminutive Douglas was known, of course, as “the little giant.”

The statue tops Douglas’s tomb, no longer set in quite so large and elaborate a park as in the postcard above. Douglas is a controversial historical figure, since he argued against Abraham Lincoln’s anti-slavery position in their famous 1858 debates, when Lincoln unsuccessfully challenged Douglas’s senate seat. If you haven’t read about Douglas since grade school, though, the details are fascinating, including Douglas’s final travels to rebellious states, attempting to stave off secession. Douglas’s death from typhoid in 1861 at 48 was at least partially attributable to those travels, which left him in sight of the IC.

“In 1856 the 705-mile-long railroad from Chicago to Cairo, the longest in the world, began regular service, and Chicago immediately felt its impact,” writes Miller. “Trade on the upper Mississippi that had previously gone downriver to St. Louis was rerouted by rail to Chicago, whose boosters began calling the Illinois Central ‘the St. Louis cutoff.’”

As we know, the mighty Illinois Central’s wide, raging river of railroad tracks still gouges a canyon through Grant Park, Chicago’s front yard.

But Senator Douglas didn’t own Grant Park, so how exactly did that part happen?

Back to Donald L. Miller, and the I&M Canal. In 1836, the lakefront strip of shoreline stretching from the site of the old Fort Dearborn on the south bank of the Chicago River, down to today’s 22nd Street, was part of the canal land carved up into lots and sold by the state of Illinois. The state acted through canal commissioners whose last names will be familiar to Chicagoans still in 2022: William F. Thornton, William B. Archer, and Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard. These three men, all on their own, decided not to sell the lakeshore. Instead, they drew up the first famous map labeling Chicago’s lakefront “Public Ground—A Common to Remain Forever Open, Clear, and Free of Any Buildings, or Other Obstruction Whatever.”

Fast forward two decades. Wealthy Chicagoans of the 1850s lived in fine houses lining South Michigan Avenue, overlooking a popular lakefront park. But Lake Michigan had eaten away at the park until storms sometimes drove the waves right across Michigan Avenue against Chicago society’s front steps. Nobody wanted to pay for building a seawall or other barriers to contain the lake. So in 1852, the city council “cut a deal with the Illinois Central, giving it a lakefront right-of-way to the terminal and freight complex it had just purchased on the old Fort Dearborn estate in exchange for construction of the badly needed dikes and breakwaters,” writes Miller.

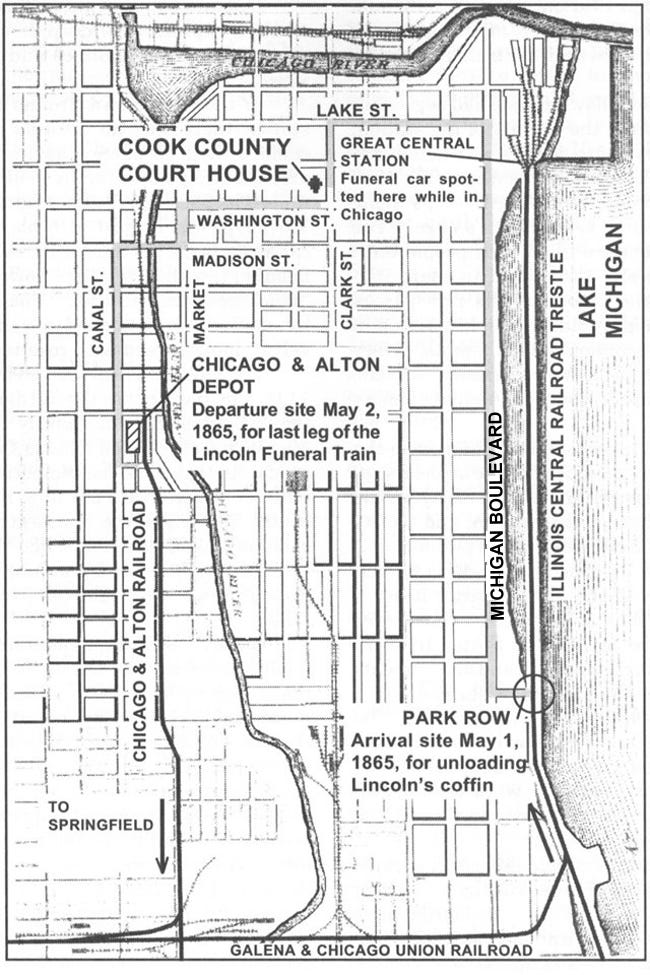

The early IC ran into Chicago on that strip of lakefront land saved by Thornton, Archer and Hubbard, though it was now underwater. So the tracks originally sat on elevated train trestles several hundred feet offshore, with a parallel line of breakwaters protecting the tracks from Lake Michigan and simultaneously saving the inner shoreline. Here is an early map thanks to the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal:

And here is a photograph of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train bound for Chicago over the IC train trestle in 1865—also thanks to the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal. The train looks like it’s literally rolling across the water.

Chicagoans would fight the Illinois Central Railroad for the rest of the 19th century over the southern lakefront in Grant Park. It would take a nearly 20-year legal battle led by Chicago merchant Montgomery Ward to finally settle the question in favor of the public. That, and a lot of landfill through all the decades since, created the Grant Park you see today.

In 1972, the IC is in the process of merging with the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad. By the end of the year, the company will technically be the Illinois Central Gulf Railroad (ICG), but everybody will still call the company and its commuter train “the IC.”

The IC (railroad) will dump—er, sell—the IC (commuter line) to Metra in 1988, the company that runs Chicago’s other commuter trains. The IC will become the “Metra Electric,” since it’s the only local commuter line that runs on overhead electrical lines rather than using diesel train engines.

January 13

Chicago Daily News: FBI hunting GI, says he planted bombs in banks

By Henry Hanson and Dennis Sodomka

His prints on letter to Daily News

By Edmund J. Rooney

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Atty Gen. John Mitchell jointly announce that last week’s time bomber is former University of Chicago research associate Ronald Kaufman. Must be a pretty big deal, to get those two guys in a room together.

Kaufman put time bombs in safe deposit boxes in three of Chicago’s biggest banks, three New York banks and two San Francisco banks—which were all disarmed successfully. Kaufman also mailed letters to media alerting them to the bombs, demanding “FREE ALL POLITICAL PRISONERS” and threatening more bombs.

Kaufman is an “AWOL Army private with a PhD from Stanford University” who was Abbie Hoffman’s “almost constant sidekick” during the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. If convicted, he’d face up to 81 years in prison. The FBI says he “should be considered armed and dangerous.”

How did the FBI finger Kaufman? Fingerprints for one thing—right on the letter he mailed to Mike Royko at the Daily News. See this week’s compilation of Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today for Mike’s reply to his new pen pal, posted later this afternoon.

Kaufman also sent letters to the Chicago Sun-Times’ Tom Fitzpatrick, Chicago Today’s Jack Mabley, Ch 5’s Walter Jacobson, the Chicago Journalism Review and the Seed. Kaufman left his fingerprints on safe deposit box contracts too, plus the safe deposit boxes and the bombs. And we thought University of Chicago students were so smart.

The Daily News says federal sources report Kaufman was never arrested, but his fingerprints were on file from his stints in the army—the first one 1956-58, under his own name; and second one this year under a different name starting on Aug. 10, 1971. Kaufman finished basic training but went AWOL a week ago.

Kaufman’s letter to Royko said he’d placed a bomb in a safe deposit box at Continental Bank, 231 S. LaSalle, and included the key. Kaufman opened savings accounts at all the banks under the name Christopher Mohr, deposited a dollar, and came back later to rent the safe deposit boxes and plant the bombs.

The bank employees didn’t recognize the FBI’s picture of Kaufman with long hair. They said he “had short hair and was well groomed.” Shown the photo, one Continental Bank employee shook her head and said, “Not with that hairdo.”

January 13, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Yellow Pages ad

No big deal, I just haven’t seen a Yellow Pages in so long.

FYR: Before the internet, if you needed to find a particular type of service or company, like say a plumber or a lamp store, this is how you found it.

January 13, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Suspect ‘quiet and nonviolent’

By Henry Hanson

The radical who planted time bombs in three Chicago banks is “quiet and nonviolent” according to unnamed sources, though the FBI calls him “armed and dangerous.”

Unnamed sources dish great gossip to reporter Henry Hanson on Ronald Kaufman, who left his fingerprints all over the bombs and letters he sent to the media. I'll throw in some extra info from the main story to round out Kaufman's bio.

Kaufman, 33, was the “almost constant sidekick” of Abbie Hoffman during the 1968 Chicago convention, says one source. “‘They gave him the nickname “Abbie’s Jewish mama.” That was because he was always worried about Abbie. He would chauffeur Abbie around town. He would try to talk Abbie out of doing things that he thought were too wild….He didn’t go along with the blood-letting philosophy of the Weathermen at that time. He said he was against that kind of violence.’”

Another friend says Kaufman was “’an upper echelon’ leader in running the Conspiracy 7 office before and during the conspiracy trial. ‘He was very level headed, a structure freak who was good at organizing things, keeping books and the budgets,’ said a friend.”

Kaufman “grew up in the wealthy Milwaukee suburb of Bayside,” “was an honor student in psychology at the University of Wisconsin at Madison” between 1955 and 1961, and served in the army 1956-58. He then earned a master’s and doctorate from Stanford, and later spent nine months in 1967 at University of Chicago as a psychiatry research associate.

Kaufman lived at 6021 S. Kimbark during his U of C days, which seems to an alley now.

Kaufman lived at 1437 W. Belmont (between Southport and Greenview) in 1968, when he was hosting Abbie Hoffman. A friend says during summer 1968, “Kaufman’s constant uniform was a yellow hard hat, a T-shirt and blue jeans.”

Kaufman mysteriously re-enlisted in the army six months ago under an assumed name—but went AWOL last week after completing basic training. That gave him time to come to Chicago to mail letters to the media, including Mike Royko, identifying where all the bombs were.

January 14, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Police probe 5 mystery murders

by Edmund J. Rooney

“Richard Stean brought his wife and infant son to his folks’ home for supper on the day after New Year’s.

“After the meal he left the woman and the boy with his parents and drove away alone in his 1971 Cadillac Eldorado. He was carrying $2,500 in cash to pay a contractor who worked on his apartment.” That’s $16,875 in 2022 money.

Richard Stean never came back to his parent’s home at 8558 S. Calumet, or his own home above the family business at 3005 W. Madison—Advance TV & Radio Sales & Service. His Eldorado was found several days later near Cabrini-Green. Now, police suspect Stean’s disappearance is connected with five recent murders.

Five other men have disappeared since last September, their cars found abandoned, and their bodies eventually washed up in the Sanitary and Ship Canal or the South Branch of the Chicago River.

The Steans are offering a $1,000 reward for information that helps find Richard—$6,750 in 2022 money. “This is a real sad mystery for us,” said Mr. Stean. “Richard was a fine son who never was in any kind of trouble. He worked seven days a week and long hours with me in the business.”

Police searched door-to-door in the Cabrini-Green area for Stean. “One investigator speculated that Stean and the other five may be the victims of a ruthless crew of stick-up men operating on the West Side.”

“‘The five murdered men all were reputable citizens who had their pockets turned inside out,’ the investigator said, ‘and we’re checking out rumors that prisoners in the Cook County jail recently have been telling of the need of killing robbery victims so they cannot testify against them court.’”

The dead men are Lee Wilson Jr. of 6655 S. University; Albert Shorter, of 4027 W. Gladys; William A. Thomas, of 933 W. 95th St.; Vernell Lollar, of 1501 S. Hamlin; and Lieutenant Scott, of 4751 W. Van Buren. Four bodies were found in different areas of the Sanitary and Ship Canal, and one in the South Branch of the Chicago River near 2051 S. Ashland. All were shot in the head.

“Assisting the police in their hunt for Stean are a number of Black P Stone Nation members and Russ Meek, a West Side activist who said ‘it’s like he went to the moon.’

January 14, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Maxine: An ear for the troubled

By Sandra Pesmen

Can you believe the Daily News didn't have an advice columnist? Dear Abby and Ann Landers are already taken. Maxine B. Inlander starts next Monday as "Dear Maxine."

She would never become a celebrity like those two sisters, but Maxine was in the Daily News, and that made her family for Daily News families, whether you agreed with her not. Which of course is pretty much the definition of family.

Maxine B. Inlander graduated from the University of Chicago. “I worked on the Daily Maroon…and later was a copywriter at several ad agencies before settling down to the business of being wife and mother,” she told Sandra Pesmen.

She worked part-time in market research, volunteered for the PTA, and most recently worked part-time as public relations director of the Highland Park Hospital. “In all these activities, Maxine has been listening to people with problems.” The article mentions Maxine has a “staff of experts”.

Maxine gives an example of a young teacher who wrote that she wanted to skip a dinner at her mother-in-law’s after work one day because she was so tired. “’But she forced herself to wash her face and put on eyelashes and go. When she arrived, her mother-in-law commented, “I see you were too tired to put yourself together.” We helped the girl understand her mother-in-law’s problem before we tried to solve hers,’ Maxine grinned.”

January 15-16, 1972

The Chicago Daily News: Insurers out to foil ghetto arsonists

By Lois Wille

Lois Wille, one of the first female reporters to break out of “women’s” stories at the Daily News, reports that the Illinois Fair Plan Association will change its procedures to hopefully spot properties in danger of arson.

The Daily News did a lengthy indepth series looking at the 1,600 fires in one square mile of Woodlawn in 1970, “most of them suspected to be arson.” “At least $1 million in insurance claims was paid in that neighborhood in an 18-month period.”

The Illinois Fair Plan Association was funded by the federal government three years ago and “permits insurance companies to pool risks in inner-city areas. It was designed to insure owners who had been turned down by individual companies, but insurance executives suspect some owners have used it to make money.”

Now the Fair Plan Association will oversee the policies directly. Chairman Clarence Rauter thinks owners “who profit from arson will be easier to spot under the new system.”

This reminded me of a recent episode of Chicago History Podcast (on Apple podcasts)— “Chicago’s Skid Row Flophouse Fires”. The ‘60s and early ‘70s are a time when fires and more particularly arson fires are widespread in Chicago’s poor areas.

January 15-16, 1972

Chicago Daily News: L.F. Palmer Jr column

A mother’s campaign for amnesty

“Lu” Palmer’s regular Saturday column today focuses on the Vietnam War, which is still not over in 1972, including for some men who refused to be drafted.

“The U.S. District Court in New Orleans last April freed Oscar E. Clinton on a charge that he refused to be drafted,” writes Palmer, because “only two members of his draft board were residents of the area it served. Clinton is white.”

Three days later, the same court upheld the guilty verdict for draft resister Walter Collins, who is Black, even though his draft board included only one member from the area—and the entire draft board was white when 2/3 of the men registered in its jurisdiction are black. “In a direct violation of the Selective Service Act, the draft board chairman lived in another county.”

The U.S. Supreme Court has denied Collins’ appeal, and he’s serving a five-year sentence in federal prison. Palmer talks with Walter Collins’ mother, “who is on the final leg of a 42-state tour…trying to win support for her son and for all young men who have been punished…because ‘they refuse to participate in an immoral and illegal war.’”

“Mrs. Collins says her son was given a particularly harsh sentence” because “He had worked on voter registration drives in the Deep South and started organizing opposition to the Vietnam War in the New Orleans black community in 1966.”

However, “Mrs. Collins is not battling just for her own son. ‘I am trying to help bring about amnesty for all men and women jailed, exiled, indicted, arrested, fired from jobs, or otherwise hurt for working to end the war and the draft,’ she said.”

“Mrs. Collins’ brave and vigorous fight for her son points to more than the racism that is and has been an inherent part of the draft system in this country. For young whites, too, have resisted the draft, gone underground to do battle with American imperialism, and died on the home front in defiance of American repression.”

“Like nothing else, the Vietnam war has unmasked official America for what it is.”

January 15, 1972

Chicago Daily News:

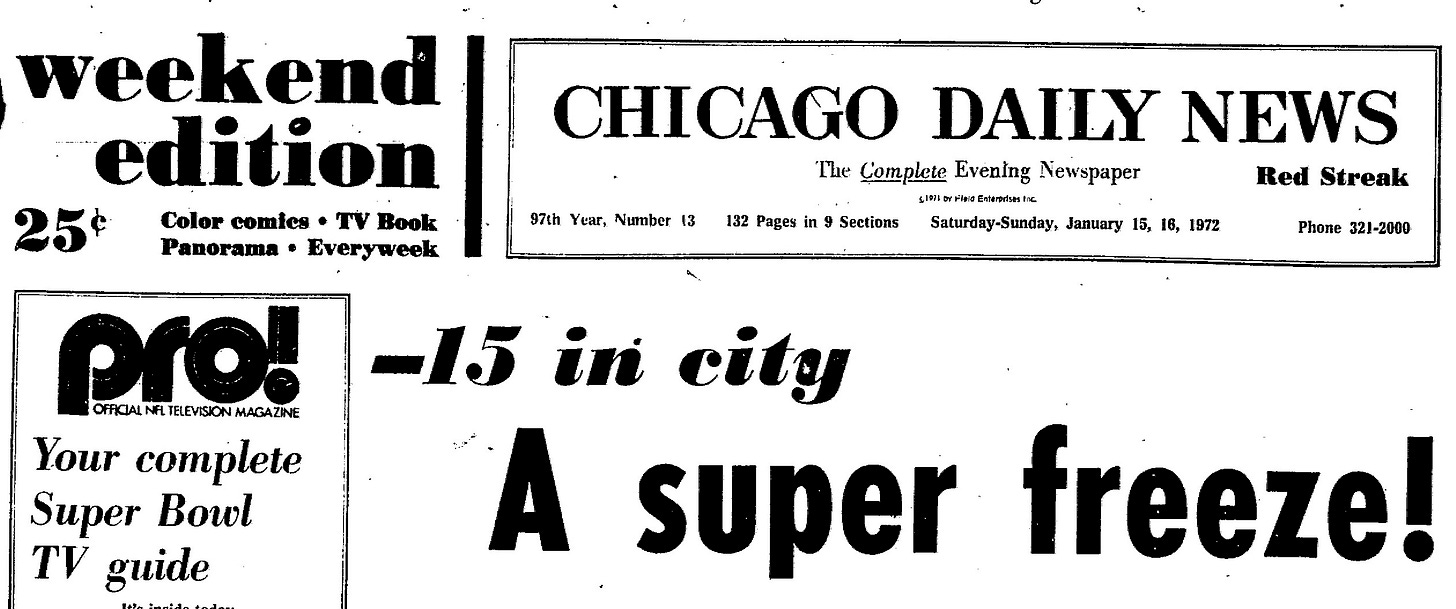

-15 in the city – A super freeze!

By Dennis Byrne

Girl, 5, freezes lips to railing

Chicago is in the middle of an artic blast, and apparently also “A Christmas Story.”

Between 1 a.m. and 8 a.m. Saturday, temperatures dropped one degree per hour until Midway Airport registered 15 below—“only one degree short of the previous record for Jan. 5”. Midway, BTW, was the official Chicago weather station 1942-1980, when it moved to O’Hare and stayed there.

It’s a massive cold front from the Dakotas, with a -55 windchill that’s brought a “rash of fires, power failures, and auto and train breakdowns”. One West Side woman is dead from a hotel fire.

And a 5-year-old girl “put her tongue and lips on a metal railing outside of the John Hancock Building Friday night in subzero weather”, getting them instantly “frozen to the metal.”

The little girl “was freed by her mother who poured hot water on the railing. Saturday, the girl was resting comfortably with a swollen lip. The girl is the daughter of Louis Sudler Jr., a Chicago realtor and head of Sudler and Co., which manages the building.” I bet that comes up every year at the Sudler family holidays!

Say, where was Chicago’s weather station before Midway? A quick search got the answer, aided by Google Streetview:

First, 181 W. Washington (formerly 162 Washington)--in 1870. Seems to be the southeast corner of Washington and Wells.

This building, “a modest, 12-story parking garage”, turns out to have a secret past revealed recently by Dennis Rodkin in a fabulous deep dive via WBEZ’s “Reset with Sasha-Ann Simons: “Today, the building is conventional, boxy and drab. But it has long-hidden a secret: It was once an ornate skyscraper, built in the 1890s with a peaked roof and columns of bay windows running up its brick façade to a frilly terra cotta crown.”

2) 427 W. Randolph (formerly 10 W ) in 1871. The closest spot now seems to be River Center at the northwest corner of Randolph and Canal.

3). 20 N. Wacker Drive (80 S. Market) 1872-73. This address seems to be taken up by the Civic Opera House building, northwest corner of Wacker and Madison.

4) The original Roanoke Building, SE corner of Madison & LaSalle, 1873-87. The current Roanoke Building includes a giant Residence Inn by Marriott.

5) The Chicago Opera House, SW corner Clark & Washington, 1887-1890. This building was demolished 1912. The spot now hosts Burnham Center, kitty-corner from Daley Center plaza. For more on the Opera House, see Chicagology’s terrific entry here.

6) Adler & Sullivan’s beloved Auditorium Tower 1890-1905.

7) U.S. Court House at 219 S. Dearborn, 1905-1925, which appears to be the southeast corner of Dearborn and Adams, now the Dirksen Federal Building.

8) Last, the University of Chicago’s Rosenwald Hall at 58th and University 1926-1942.

January 16, 1972: The Mighty IC #2

Chicago Tribune

no byline

“The subzero temperatures turned the Illinois Central Railroad into a commuter’s nightmare yesterday,” the Trib reports. This is the drawback to an electric commuter train, versus a train pulled by a diesel engine.

“Some trains were delayed as much as three hours because of frozen switches, downed power lines, broken rails, and shorted signals.”

“We’ve had terrible problems,” IC spokesman Robert O’Brien told the Trib. “Crews are working throat the weekend in hopes of having a normal rush hour Monday….Our workmen are on the job around the clock, and some are so tired they have cried.”

Do you dig spending some time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the book being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.