To access all website contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 is part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. Follow THIS CRAZY DAY on Twitter, @RoselandChi1972.

Cold. Blooded. Murder.

And so many murders. What was the Tuskegee Study but a slow mass murder? In addition, there’s a grisly group murder this week; a sadistic murder from last week, decried in an op-ed; and an especially poignant future death you will sadly see coming.

July 31, 1972

Chicago Today

A most unusual cigarette ad, from Carlton. This is the entire ad—not just the small print from a larger ad with, say, a young couple on a sailboat or something.

July 31, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender: editorial

“The shocking revelation by the U.S. Public Health Service of an experiment known as the Tuskegee Study in which 600 poor and uneducated black men, from Tuskegee, Alabama, were used as guinea pigs to study the effect of syphilis after death, could not have descended to a lower depth of moral responsibility,” writes the Defender’s editorial board.

See July 25 for coverage of the first expose of the Tuskegee Study.

“The sole objective of the experiment was to determine from the autopsies what the disease does to the human body. That information is already available by hundreds of cadavers in scores of medical school morgues where patients prior to their deaths have donated their bodies to science.”

…. “The human body, black or white, even after death, is sacred. It should not be used as a toy to be dismantled, torn apart just for curiousity’s sake. What good is the Tuskegee Study?”

July 31, 1972

A giant national political bombshell, via front pages and one smaller headline, from today and tomorrow:

From the Tribune’s page 3—because this headline describes such a weasely McGovern strategy, which turns out to be accurate when you read the article:

August 1, 1972

Imagine being so prominent that you’re a top four pick for VP. Almost none of us will ever be that prominent, even if the job is kind of a joke.

Then a few decades later, nearly everybody reading Substack thinks, “Who the heck is that?”

August 1, 1972

Chicago Today

by Milton Hansen

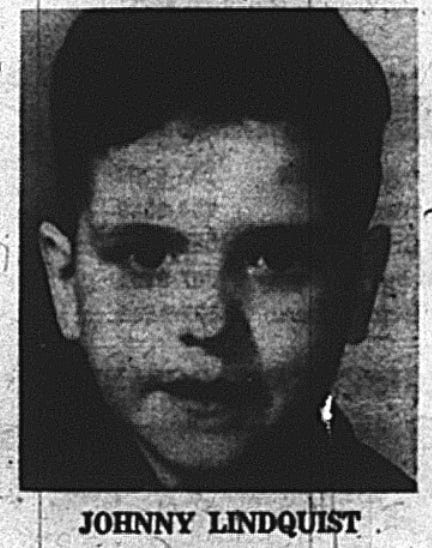

“Johnny Lindquist prayed each night not to be sent back to his parents, but the Circuit Court judge who ordered him home last March 28 apparently didn’t hear those prayers.”

That’s the chilling first sentence Chicagoans read of what would become an all-consuming tragic tale playing out across all four major dailies, every day this week and continuing intermittently for months. Chicago Today covered Johnny Lindquist first.

Note: It’s unclear whether the Defender covered Johnny Lindquist before its first digital archive entry in September with his name. The Defender’s digital archives and microfilm are unfortunately not complete. Entire days will come up empty of any articles at all, about anything. Usually, it’s just a day here and there. But lately, entire weeks have come up almost empty digitally. Going back to the library to check the microfilm, I was able to fill in many missing days, but not all. This week, for instance, August 2 and August 4 were missing. From what was available, there were no Johnny Lindquist articles in the Defender this week.

But that wouldn’t be unusual. The Defender normally passes on stories of murdered, missing, or otherwise hurt white children, even the most high profile cases, unless a Black person is somehow involved—as in the current case of Joseph O’Shea. Instead, the Defender covers stories of Black children that don’t make the major dailies. So far in 1972, those have been one-off Defender articles rather than the constant blanket coverage Johnny Lindquist will get in the major dailies, or as regular readers will remember, Harold Drumm saw earlier this year.

The major dailies do cover stories about hurt/missing/murdered Black children, but obviously not like the Defender. The case of Joshua Taylor, a Black child from Cabrini-Green, appears to be an odd exception. Joshua’s coverage came entirely from the major dailies, with none in the Defender that I could find. The Daily News and Tribune followed Joshua’s story after he was shot by a sniper near his Cabrini-Green home on December 7, 1971. (I don’t have complete enough microfilm coverage of Chicago Today and the Sun-Times to definitively say that they never covered Joshua, but I didn’t see him in either paper, and they don’t have accessible digital archives.)

However, the major dailies jumped in late on Joshua’s story. The first Daily News article came on December 22, 1971, two weeks after Joshua was shot—and probably only then because he was one of their paperboys. Joshua’s coverage wasn’t constant, and once he could take a few steps with Gale Sayers (see April 5), he never made the papers again. One of Joshua’s Daily News clients started a fund for him that reached about $3,500 ($23,625 in 2022) by his last newspaper appearance.

Compare that with Harold Drumm, whose face and name were plastered across the papers for weeks starting April 10 after his arm was severed while he was playing in a trash compactor behind a South Side Zayre. Harold benefited from funds raised by WGN’s king of morning radio, Wally Phillips, and matched by 1972 Chicago’s resident famous rich philanthropist, W. Clement Stone. When last we heard, Harold’s fund was expected to reach $27,000 ($182,250 in 2022).

BTW, there are one-off tragic stories about children of all backgrounds in all the papers every week that I don’t include, waiting instead for unusual, high profile and/or continuing cases that consume the city, like this one.

“Today, the 6-year-old boy is in a coma in St. Anne’s Hospital, his skull fractured and his body a mass of bruises.

“His father, William, 31, of 4729 W. Erie St., is being held in Cook County Jail on charges of aggravated battery.

“It was something that never should have happened.”

Johnny Lindquist’s background, as we hear it today: At about age two, Johnny was sent as a foster child to Robert and Florence Karvanek, who then lived on the Southwest Side. We don’t hear what caused Johnny’s first removal from his family.

The Karvaneks moved to Tigerton, Wisconsin near Green Bay when Johnny was four, along with another foster son. Johnny’s natural parents never visited him anyway, and the Karvaneks decided “the city’s Southwest Side was no place to raise children”. The Karvaneks bought “a 40-acre farm with a trout stream and barn for the pony the boys would ride.” Mr. Karvanek works there as a painter.

Johnny was ordered to visit his parents for Christmas in 1971, and returned with stories about his father’s violence. “He said that, when he got mad at something on the television, Lindquist threw a chair thru the screen,” Mr. Karvanek told Today’s Milton Hansen.

The Karvaneks tell Chicago Today there was no hearing for them to attend and appeal Johnny’s return to the Lindquists. Per Today, “Mrs. Lindquist said a caseworker told her the boy’s presence in the house would mean a larger welfare check.” Today hasn’t talked directly to Mrs. Lindquist, so presumably she said this to police.

“‘Johnny must have known what it was going to be like with his parents,’ Florence Karvanek says. ‘Each night he would pray, ‘Please God, don’t send me back home.’”

“Irene Lindquist told police Johnny was beaten Friday night because he wet his bed. She said her husband would tie the boy’s wrists and legs with a plastic clothesline and suspend him over a door for punishment.”

“‘Johnny must have gone through four months of hell,’ Mrs. Karvenek said. ‘I don’t see how anyone could treat a child like that.’”

The Karvaneks sit next to Johnny’s bedside now in the intensive care unit.

“Johnny holds on to his foster father’s finger and tries to open his swollen eyelids. ‘We’re going to take you back to Wisconsin, son,’ Karvanek says. And Johnny tries to squeeze Karvanek’s finger a little harder.”

August 1, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times

“Strange but true,” writes our Roger, first film critic to win a Pulitzer Prize. “Animated pornography is a lot more fun than films of real people doing the same things. But then movie pornography has never seemed like much fun to me; the abstract notion of a sexual fantasy loses something when we see real people acting it out. They aren’t disembodied enough, if you see what I mean.”

Porn has improved since stag nights, says Ebert, but he’s still not impressed.

“Animation, however, can separate sexual fantasy from the physical impossibilities of real life, and that’s what happens in ‘Fritz the Cat.’ Take the bathtub scene, for example: There are maybe a dozen animals in that bathtub at the same time, and the staggering proportions of their mutual grope makes it funny, not dirty.”

“Freed from the embarrassment of photographing real people, the movie is able to demonstrate how ridiculous, how funny, how revealing of human nature, our pornographic fantasies are.”

This is not an R. Crumb movie, Ebert notes, but a movie by Ralph Bakshi based on the characters of that uber-underground comics artist. Fritz the Cat is a white liberal college student dropout who careens around “a tour of the last decade” including the civil rights movement, smoking pot, orgies, and burning down New York University. It’s all based on real times and places, Ebert writes, just like the opening shot pictured above.

“It is, at least, one more brave demonstration that feature-length cartoons don’t necessarily have to be made for kids,” Roger concludes, “and that animation is the most unfairly neglected of all movie processes.”

Fun Fact: An old pal of mine who will enjoy reading this had a Fritz the Cat movie poster hanging on his teenage bedroom wall, so I’m well aware that the ad below is a family-friendly version for the 1972 newspaper. In the real poster, Fritz’s right paw is smack on the girl cat’s right breast. I was surprised my friend’s mom went along with that. He was surprised that I was surprised.

Here’s the real thing:

August 1, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender

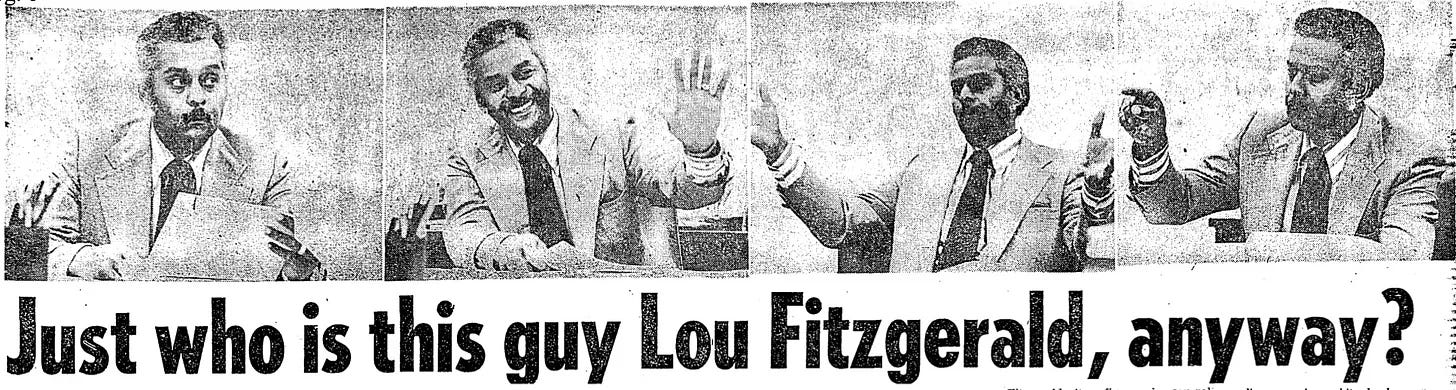

by Louis Fitzgerald, Jr.

Why did the Defender go to the trouble of typesetting a special disclaimer for a letter from a reader—when they run this piece not in the letter section, but as an op-ed article?

Because Louis Fitzgerald is not your average correspondent. His views are trenchant, plain spoken, and many people today would call him racist despite the fact that he’s Black. While the Defender takes care to separate itself from Fitzgerald with its disclaimers, the paper’s leadership clearly thought its readers should hear his viewpoint.

The Defender’s Robert McClory will write a profile of Fitzgerald in November, and he’ll soon become a regular Defender columnist. See TCD1972 on June 10 for a dive into Fitzgerald’s fascinating background.

Today Louis Fitzgerald writes in reaction to a sad story covered by several papers last week, which attracted sorrowful reader letters lamenting the state of society. The lede paragraphs in each version are depressingly similar, because the facts of the case are so stark and simple.

The Defender’s headline for the story by Joe Ellis, on July 25:

“An elderly ice cream vendor was fatally shot in a robbery attempt Monday afternoon on the sidewalk at 111 E. 47th St.”

The vendor only had $3, which is $20.25 in 2022 money.

74-year-old Sandy Reed, of 4321 S. Michigan, was “living on a veteran’s pension and supplementing his income from a pedal-driven [ice cream] cart” according to police Sgt. William Boresczky from Wentworth Homicide.

Reed was peddling ice cream when two teenagers demanded his money. “Reed ran, yelling, into the doorway of the building…for someone to call police. He then ran back to his cart, the witnesses said, and appeared to be trying to chase the youth away, who was then sitting on the cart.

“The youth then pulled a gun from a pocket, police were told, and shot Reed in the chest.”

According to the Sun-Times version also from July 25: “Witnesses said one of the youths told Reed he should have given him his money, then shot him once in the chest.”

The shooter jumped on a westbound 47th street bus, and Reed died an hour later on an operating table at Michael Reese Hospital.

Per the Sun-Times account, police arrested one 15-year-old and one 16-year-old, who were taken to the Audy Home for children. It wasn’t known whether they would be tried as children or adults.

This is, in a city like Chicago, a small story. But sometimes a small story has a big impact on readers for precisely that reason.

Louis Fitzgerald’s brutally direct lede:

“Alright, OK, you win, but you better believe I am not in love with you, you filthy, dirty, little punks who have allegedly murdered the 74-year-old ice cream vendor on 47th st.”

He goes on: “This needless, senseless killing was so unnecessary. So brutal; so wanton; and so cheap that it makes one wonder why and what makes life so cheap in the, not only the Black community, but any community. As stated before I am not a lover of the Chicago Police Department but I’ll be damned if I can stomach Black on Black Crime!”

Fitzgerald wonders “Where and when will the local politicians begin to crusade against Black on Black crime?” and “What kind of parents are we producing?”

“We all know Blacks have had to live under oppressive conditions; we know of the bigotry, racism, unemployment, and inadequate school systems, but must these conditions be a necessary adjunct for wanton murders?”

He advises that courts need to deal out “stiffer sentences” and hold parents accountable for their teenagers’ crimes— “and you will find a decline in youthful marauding.”

“The police Department has made some drastic mistakes,” writes Fitzgerald. “ (1) by being racists; (2) by being too stupid to understand the needs of the people and (3) not being able to police themselves…however, what qualifies us to condemn the police when many of us are no better than they are?”

…. “We tend to overlook and comment how awful the crime and proceed to live in fear and buy German Shepards, iron bars, additional locks, and carry guns for self protection which is not the way to solve the problems.

“Blacks had better get off their butts and begin to take some action and not leave the driving to someone else….

“Now run and tell that!”

August 1, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender

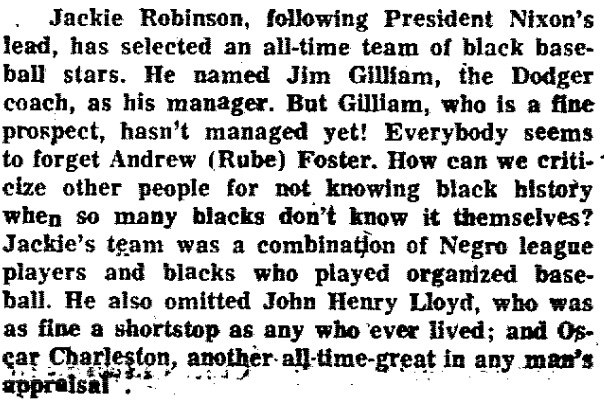

Note: See the Chicago History Podcast episode #504, “Chicago Baseball: Rube Foster and American Giants” for more background on the Chicago angle to this story. The Giants played for a time at the now-vanished South Side Park after the White Sox moved into Comiskey Park, and at Comiskey too after 1941 when the Sox were out of town.

August 1, 1972

Chicago Daily News

August 1, 1972

Chicago Today

Letter #1 is from an official of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization, who brings up points that make you realize skyjacking is even more dangerous than you already figured. There are hijackings going on this week, by the way, but there’s only time for so much 1972 news in any one post.

August 2, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times

Last week, two Black youths broke into the O’Shea home at 9311 S. Throop, one of two white families left on the block in racially changing Brainerd, just north of Roseland. The teens beat 11 (or 12)-year-old Joseph, who was home alone, leaving him in a coma. Then they set fire to a rug and turned on the stove’s gas burners. Luckily Joseph’s family returned before the fire reached the stove. He’s still at Little Company of Mary Hospital in Evergreen Park following surgery for a fractured jaw. See TCD1972 on July 28, July 29 and July 30. A 12-year-old has been arrested in the attack.

Now, the O’Shea’s neighbors have started a fund for Joseph and another local boy.

“The decision to help both the families of O’Shea and the family of William Vickers, 7—whose eyes were burned with cigarets on May 31 allegedly by the same suspect—came after a community meeting Monday night. Mrs. Gail Christian, secretary of the Brainerd Community Council, said it was also decided to increase on-street time of a private crime patrol and to ask more police protection of Police Supt. James B. Conlisk Jr.”

Chicago Today reports that Mrs. Shirley Griffin, Vice President of the council, says the fund has already collected $40 from about 100 people.

“The council is teaming with another predominantly black group of the South Side, the Brainerd Action Committee, to pressure juvenile judges to become stricter with delinquents.

“Howard Brookins, treasurer of the committee, said groups of at least 50 persons are going to Juvenile Court to ‘let the judge know we don’t want these punks back in the community.’”

If you’re a regular THIS CRAZY DAY reader, you’ll probably want to follow Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today too.

August 2, 1972

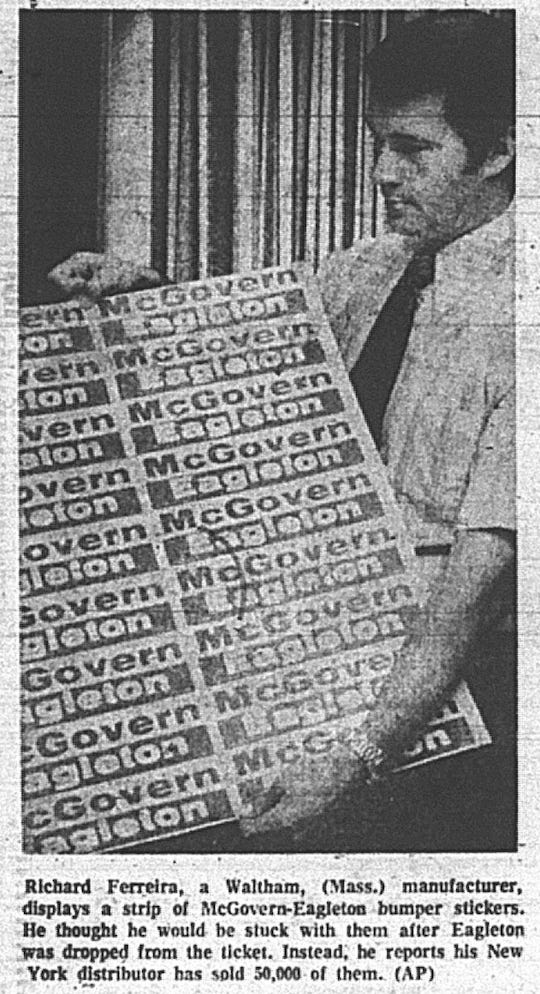

Chicago Daily News

David Ross, president of the company contracted to churn out McGovern-Eagleton tchotchkes, was afraid he was stuck with a warehouse of junk. Instead:

“We have such a demand we are now manufacturing more.”

Some of these bumper stickers are going to collectors who’ve ordered lots of 1,000 each. Ross claims one woman told him, “Nobody is going to get these Eagleton buttons from me—they’ll be worth a fortune.”

But exactly 50 years later, you can get this 3.5” button for as little as $2 on eBay. And I’m pretty sure this is the only place you’ve read about the 50th anniversary of the only time in U.S. history that a vice presidential candidate dropped off a major party ticket.

August 2, 1972

Chicago Today

by Pat Krochmal and Milton Hansen

“A Family Court judge returned Johnny Lindquist to his natural parents despite warnings by social workers that the boy’s father was ‘immature,’ CHICAGO TODAY has learned.

“Johnny, 6, is in critical condition today with a fractured skull at St. Anne’s Hospital.”

Today’s report fills in some blanks on Johnny Lindquist’s short life:

Johnny Lindquist was placed in St. Vincent’s orphanage immediately after birth in 1965, where he joined his sister Jane, two years older. “Mrs. Lindquist said the children were placed in the orphanage because she had tuberculosis.”

“Records show that from the time of their marriage, the Lindquists have been on welfare. Caseworkers who visited the many apartments the family lived in called William Lindquist ‘immature…a marginal person…unable to assume the responsibilities of a family.’ He has never held a steady job.”

St. Vincent’s asked the Lindquists to give up the children for adoption, but they refused. Jane was sent back to them, while Johnny went directly to Robert and Florence Karvanek on the Southwest Side as a foster child. The Karvaneks moved to a small farm in Wisconsin later, where Johnny was happy with his foster brother, and they had a pony to ride.

But in December 1970, “the Lindquists petitioned Family Court for Johnny’s return. A caseworker told Mrs. Lindquist that Johnny’s presence would mean a larger welfare check.” Was that a state caseworker? Or someone from Catholic Charities? We don’t know, assuming the statement is correct.

Judge Thomas Rosenberg held three hearings in 1971 and “heard evidence from a Catholic Charities caseworker stating that Johnny should not be returned to the Lindquists” Today reports, but confusingly adds: “Whether Rosenberg granted or denied the Lindquist’s request will not be known until the records of the case are released by the court.”

That’s because the Lindquist records were “removed from public files yesterday” by the Family Court supervising judge, pending an investigation. We read that Johnny visited his family’s home once in his entire life, for Christmas 1971, and called it “a madhouse” when he got back to the Karvaneks.

Judge Rosenberg is former alderman of the 44th ward. His resignation after being elected an associate Circuit judge in 1968 opened the seat first for Ald. Bill Singer’s election, and then current 44th ward Ald. Dick Simpson, after redistricting put Singer into the 43rd ward. They’re both key players in the meager independent faction of aldermen in City Council.

“Ralph Bauer, Chicago regional director of the state Department of Children and Family Services, said that after the court session, ‘there was a discussion with the understanding that the return of the child was the recommendation of the court and we proceeded to return him.”

Today speaks with Dr. Edward Flutterman, director of the University of Illinois Medical Center’s child psychiatry clinic, who explains that “Under present law, a child must belong to someone—he is a piece of property in the custody of its parents or, if need be, the state. What is needed is a legal concept which endows the child with its own rights and appoints a necessary agency to protect those rights.”

Chicago Daily News

by Karen Hasman

The Daily News account agrees that the Karvaneks were never allowed to testify at Johnny’s 1971 custody hearings, but if anything, this report muddies the waters even further.

With no testimony from the Karvaneks, “when a social worker recommended that Johnny be removed from the Karvanek home and sent back to his natural parents, Juvenile Court Judge Thomas Rosenberg thought he was doing the right thing,” writes Karen Hasman.

“Court records show there was no formal order to return Johnny home. But a decision was reached at a hearing on Feb. 25 that an attempt should be made to return the child to his natural family, who had asked for his return…jointly by Judge Rosenberg, the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services, and Catholic Charities”.

Recall that per Chicago Today, Catholic Charities specifically recommended not sending Johnny back. Ralph Bauer, Chicago director for the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services, tells the Daily News that “The caseworker was not able to detect anything that showed that Johnny was unhappy” about going back to his natural parents. “When the parents show evidence of trying…we go along with it.”

Does Bauer mean the Catholic Charities caseworker? That’s left unclear. Johnny’s Catholic Charities caseworker had left the agency, and refused to speak with a Daily News reporter.

Chicago Sun-Times

by Calvin Lindsay

Johnny Lindquist may not live. His biological mother, Irene, “told police her husband…tied the boy’s arms and legs with rope, then hung him upside down for 8 hours a day for days in a row.” Mrs. Lindquist only called the police on Friday because Johnny was unconscious.

“Johnny was being punished, his mother said, because he wet his bed. She said he wet his bed in rebellion because he wanted to return to his foster parents.”

Chicago Tribune

Additional info from the Trib: Mrs. Karvanek says Johnny’s Catholic Charities caseworker told them in March that he would be returned to the Lindquists. “They said we couldn’t be in contact with him again.”

When Johnny first came to the Karvaneks, “He stuttered and wet his pants,” she said, but those problems cleared up. His ordered visit last Christmas with the Lindquists was his first time in their home, per Mrs. Karvenek. After the Karvaneks moved to Wisconsin, she says, “They never even sent him a birthday card.”

“Johnny will be 7 on August 28. His father is scheduled to appear in North Felony Court on Sept. 11.”

August 3, 1972

August 3, 1972

Johnny Lindquist’s story is now front page news.

by Ronald G. Bergquist

The sad tale of Johnny Lindquist is an example of how news stories can change as new information comes to light. Johnny did go directly after birth to St. Vincent’s orphanage, but it turns out he did not leave St. Vincent’s for the Karvaneks. First, Johnny went to the Klein family of Oak Forest at age three months. He lived with the Kleins until 1968, when Mr. Klein was hospitalized with kidney disease, from which he died in 1970. Catholic Charities told the Kleins they were taking Johnny back during Mr. Klein’s initial kidney failure, and they assumed it was due to Mr. Klein’s illness.

Neither family knew about the other one. They met for the first time at St. Anne Hospital, where Johnny Lindquist remains in critical condition in intensive care with a fractured skull and bruises over his entire body. The Karvaneks have traveled from their current home in Wisconsin to be with Johnny, and try to regain custody.

Mrs. Bernadine Maynor—the former Mrs. Klein, Johnny’s first foster mother— tells Chicago Today that Johnny had a one-day visit with the Lindquists for Christmas 1966, when he was a little over a year old. The Lindquists picked Johnny up at 11 a.m. and brought him back at 10:00 that night.

“What we saw was unbelievable: He had a wet, filthy diaper on, was running a fever and was filled with scratches from the parents’ dogs. The clean clothes and food we had provided hadn’t even been used,” said Mrs. Maynor.

In a separate article, we learn that “reporters could not reach Judge Rosenberg, who is assigned to the Criminal Courts building at 26th Street and California Avenue.”

Chicago Today also runs a full inside page of pictures with Johnny accompanying a short interview with Mrs. Karvanek. “If all kids were as good as Johnny it would be a perfect world,” she tells Today.

After Johnny’s 1971 Christmas visit at the Lindquists, says Mrs. Karvanek, he came back with a bloody nose and told his foster parents how his natural father had thrown a chair through the TV, while his two younger brothers picked on him and shoved him against a brick wall. He called it “a madhouse.”

“Her voice is stronger now, the anger deep within her rising just a little:

“‘He was such a lovable kid, always smiling, so good. Everybody liked to just grab him and hug him. I can’t understand why anyone could beat him.

“‘The day he left us he told me wasn’t going to be good when he got [back to the Lindquists] because he wanted to come back to us and thought that if he was bad they would send him back. I told him not to be foolish, he didn’t know how to be bad.’”

Chicago Daily News

By Ellen Warren

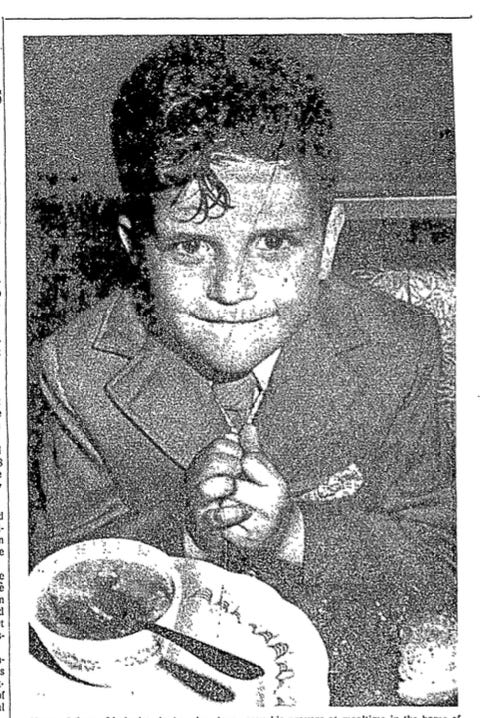

This heartbreaking picture of Johnny Lindquist takes up most of the lower righthand of the News’ front page.

“On Aug. 28, Johnny Lindquist will be 7 years old—if he can hold on long enough.

“Johnny is still in critical condition…with a fractured skull. He has been kicked and beaten. There are rough red welts on his back.”

There are more pictures when the story jumps inside, and an unexpected comment from Judge Rosenberg.

“Thinking back, Judge Rosenberg doesn’t recall Johnny’s case,” writes Ellen Warren. “‘I have no knowledge of the case at all. I would hear 60 or 70 of these cases a day,’ he said.

“Rosenberg said what probably happened was that the public defender, at a custody hearing last winter, told the judge that the natural parents could take care of their son.

“‘They have to show that they have a home, that they can keep him clean and they can take care of a child,’ Rosenberg said. ‘We always try to return the child to his natural parents…It’s not that they can’t give the niceties of life like the foster parents. If that were the case, most of these persons would lose their children.’”

Do you love the Wrigley Building? It’s not just a pretty face.

CHECK OUT:

The Wrigley Building Part Two: Built On Spearmint

August 4, 1972

Chicago Tribune: Siskel reviews

by Gene Siskel

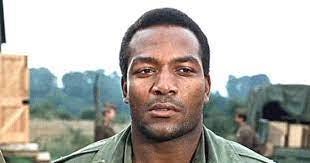

“A building in West Germany collapses, killing the President of the United States and the speaker of the House of Representatives. The Vice President [Lew Ayres], confined to a wheelchair, gets the bad-good news and promptly sets the cabinet on its collective ear by announcing that he is too sick to handle the top job.”

So who’s next in the line of succession? “According to the 1966 rules of succession, the president pro tempore of the Senate [Sen. James Eastland of Mississippi now has the job] is next.”

In “The Man,” that’s Sen. Douglass Dilman of Massachusetts.

“What’s the big deal?” asks Gene Siskel—rhetorically, since we all know who stars in the movie. Answer: “His skin—it’s black.”

Without having gotten a film degree, I am going to guess that this may be the first “first-Black-man-becomes-president” movie. Siskel tells us the movie was originally made-for-TV by ABC, which then decided it was good enough for theaters. Siskel says they were right.

“And as Douglass Dilman, a quiet intellectual played by James Earl Jones, learns of his new job, his terror-filled face turns toward the camera, the image is frozen, and the film title appears in big, gold letters: ‘The Man.’”

It’s based on the 1963 novel of the same name by Irving Wallace, best-selling 20th century author and born incidentally in Chicago. Wallace wrote fun dispatches from the July 1972 Democratic National Convention for the Sun-Times, which we’ll sample in the upcoming addendum post focusing on more craziness from that week in Miami.

“‘The Man’ is one of the most entertaining motion pictures of the year,” writes Siskel. “Most of the credit for its success belongs to James Earl Jones, who, with this film and ‘The Great White Hope’ two years ago, deserves recognition as one of America’s finest actors.”

By 2022, we all know and love James Earl Jones, of course. As the voice of Darth Vader, Jones is as close to immortal in the film world as you get. And his role as grouchy Terence Mann looms large since “Field of Dreams” has become one of the most beloved films of the late 20th-century.

But my favorite James Earl Jones performance is his very first appearance on the big screen.

Back to Siskel’s review:

“What Jones does is bring intelligence to the story. It could have been an exploitation movie, and by that I mean a movie that featured bigotry. Right now many of the advertisements for ‘The Man’ are playing up that angle. Fortunately, in the movie, the southern senator who doesn’t like Jones’ pigmentation [Burgess Meredith] has a small part.

“Jones, however, makes us feel what must be awesome pain in his heart when he realizes what it is like to be President and hated. If you ever have really been scared in your life—so scared that it physically hurt inside your chest—then you will be enthralled by the Jones performance.”

President Dilman takes office just seven weeks before his unidentified party’s nominating convention, and the party honchos want to keep him under wraps and nominate a white guy. “How Douglass Dilman reacts to being politically castrated forms the story line,” Siskel tells us.

Guess what? You can watch “The Man” for free on YouTube at the link above—and it starts with Jack Benny delivering a monologue at what is supposed to be the White House Correspondents Dinner, as news breaks about the President’s death.

That big James Earl Jones close-up Siskel mentions comes right around the seven-minute mark.

And as the cabinet exchanges one-liners with each other, Burgess Meredith, the prominently racist senator, says: “The White House doesn’t seem white enough for me tonight.”

August 4, 1972

Chicago Today

by Jack Queeney

All the papers run stories, though they’re short, when 25-year-old Peter La Rocca is “brutally beaten and stabbed late last night as he bicycled thru Palmer Park” in Roseland.

“Police said that La Rocca, accompanied by a friend, had been cycling around the park at 112th Street and Vincennes Avenue, when he was attacked by almost a dozen youths who demanded his racing bike.

“When La Rocca refused, police said the youths began beating him and stabbed him twice in the upper chest, once in the right shoulder and twice in the back.”

Police Sgt. Francis Lee of Burnside homicide classified the stabbing as a racial incident, the second in two weeks in the park. “More than two weeks ago a white man was set upon by a group of black youths and beaten in the park,” writes Today.

The Daily News calls it the second area racial incident in a week due to the home invasion on July 26 at 9311 S. Throop, when 11 (or 12)-year-old white Joseph O’Shea was brutally beaten by two Black teens who invaded his home at 9311 S. Throop. See TCD1972 on July 28, July 29 and July 30.

“According to La Rocca’s friend…the blacks marched across the park and deliberately blocked the cyclists’ path.

“‘After they did this,’ Lee said, ‘they swarmed all over La Rocca, beating and stabbing him before taking his bike.’”

La Rocca, of 11742 S. Normal, is one of three sons of Mrs. Pieta La Rocca, 55, “a widow for 19 years” who “pleaded for more police protection in the racially changing neighborhood.” The former La Rocca home is now a vacant lot.

“Mrs. LaRocca kept a vigil at [Roseland Community Hospital] while her son underwent three hours of surgery.” He remains in serious condition.

Peter La Rocca works in marketing at Union National Bank of Chicago, after attending Loyola University on a full academic scholarship.

August 4, 1972

Chicago Tribune

no byline

“A bullet fired early yesterday smashed the window of a business owned by a man who has protested the brutal beating of 11-year-old Joseph O’Shea, who was attacked in his home last week,” writes the Trib in an unbylined article.

As mentioned earlier, white Joseph O’Shea was home alone last week when two Black youths broke in, beat him up, and left him in a coma. The O’Sheas are one of two white families left on the racially changing block. See TCD1972 on July 28, July 29 and July 30.

“Howard B. Brookins, owner of the Brookins Funeral Home at 9315 S. Ashland Av., found the door window shattered when he went to work yesterday, he told police.”

“Brookins is treasurer of the Brainerd Action Committee, a predominantly black group that launched a campaign to fight crime in the community hours before the shot was fired. The committee and the Brainerd Community Relations Council have united in the fight.”

Chicago Today reported on August 2 that Brookins said his group is sending up to 50 people to Juvenile Court to “let the judge know we don’t want these punks back in the community.”

“‘I can only surmise [that the window was broken] because of the statements I made,’ Brookins tells the Trib.

Howard B. Brookins is also the father of 21st ward Ald. Howard Brookins, Jr., who has represented the ward since 2003, and is still in office in 2022.

“The groups met Wednesday to organize citizen patrols to help police and to aid Joseph O’Shea.”

August 4, 1972

August 4, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times

Shirley Knutson for governor!! Sorry, couldn’t help it.

That’s right—you couldn’t just buy pre-packaged meat in many grocery stores in 1972.

Background for next letter: Abortion in 1972 is exactly like it is in 2022—a big political issue as voters try to decide how legal it should be, or not, because it isn’t protected as a constitutional right by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The letter concerns an article published in the Sun-Times on July 27 by Eunice Shriver. She is actually Eunice Kennedy Shriver, prominent as the sister of assassinated President John F. Kennedy and Sen. Robert Kennedy, as well as then- living Sen. Ted Kennedy. Shriver wrote a lengthy anti-abortion opinion piece originally for the Los Angeles Times.

Shriver is most remembered for her long interest and work around intellectual disabilities, which led her to found the Special Olympics in 1968, in Chicago. Though it has nothing to do with the following letter, Eunice Shriver’s husband is also about to become George McGovern’s running mate because Sen. Tom Eagleton just dropped out of the race.

Eunice Shriver has five children in 1972, and will ultimately have 19 grandchildren. Like all Kennedys, Eunice Shriver is Catholic, which surely informed her opinion on abortion—though in reality, the majority of Catholics were not anti-abortion even then. The letter writer below clearly feels Eunice Shriver’s great wealth informed her abortion opinion too.

Unfortunately, I somehow didn’t copy the first part of Shriver’s piece during my microfilm research, and only have the last half of it. I don’t have access to a Sun-Times digital database for 1972, though maddeningly, it does exist, just beyond the grasp of most people. Even a cheap trial subscription to the LA Times couldn’t get me to an archive back to 1972 with Shriver’s full article. So.

Here’s what I can tell you from the second half of Shriver’s piece: She decries abortion and proposes a campaign called One Million for Life, in which she hoped to get one million couples to sign up for a registry volunteering to adopt children.

According to Shriver, “when so-called unwanted children are adopted, studies show that they may bring great joy to their new parents and grow up to become successful and well-adjusted adults.”

Shriver admits that “Much spiritual courage is required to carry a child to term and then give it up.” But she does not, at least in the last half, note the physical and financial requirements that might make a full-term pregnancy fatal or impossible.

Maybe Shriver allows for those issues in the first half. However, she closes with the bizarre and insulting implication that anyone who is pro-choice no longer values human life because of the Vietnam War.

“Life has been cheap to us since we have been mired in Vietnam,” Shriver writes. “And I fear there has been a transference of this attitude to any matters here at home. That inclination must stop.”

This gives her a circuitous way to bring in brother Robert F. Kennedy, and on her side. RFK’s assassination is still a fresh wound for the country, while most of his questionable actions are yet to be written about in-depth, so in 1972 he has a particularly saintly status.

“I hear my brother Robert’s words in a song about Vietnam and the youth that we left there. Which one, he asked, would have built the bridge? Who would have written the poem or been the peacemaker? We cannot sing this song just for the dead of war.”

A key phrase comes next:

“Those who oppose us”—people who are pro-choice— “cannot have it both ways—to abhor death in Southeast Asia while rejecting the case for life in Los Angeles or Manhattan.”

Shriver’s conclusion: “We must act where we have the power to act and move to preserve what others would abuse and destroy. For we are human beings. The destruction of human life is contrary to our nature.”

August 4, 1972

Johnny Lindquist remains front page news. Inside: “Johnny Lindquist lies near death today, kept alive only by a machine,” writes reporters Warren Shore and Milton Hansen.

“The constant vigil by his foster parents, the unceasing efforts of the St. Anne’s Hospital staff and the prayers of thousands of persons who never knew the six-year-old boy were unavailing.

“Doctors say the beating the boy received caused such extensive damage to his brain that, even if Johnny should survive, it would only be as a vegetable.”

The debate continues about the current law on child custody.

“William Sylvester White, supervising judge of Juvenile Court, admitted that the system of virtually unlimited power over children given to the State Department of Children and Family Services ‘might need some rethinking.’”

But Judge White “was still unable to give an accurate description of what happened in the Lindquist case.”

White tells Today that Rosenberg granted the state request to send Johnny back to the Lindquists for a four- to six-month placement, but “maybe” there should have been progress reports.

Yet Today says a letter from the Catholic Charities caseworker shows there were progress reports, and three visits made to the Lindquists after Johnny was returned. “Reports on those visits show that Johnny expressed a desire to return to his foster parents but made no mention of beatings.”

The caseworker decided the other four Lindquist children could stay with Mrs. Lindquist as long as her husband was in jail, even though she never intervened when her husband tied Johnny up and hung him upside down for several days.

“Irene Lindquist has never visited her stricken son, but a bedside vigil has been kept by Florence Karvanek, Johnny’s foster mother.”

by Dennis Byrne

Although Judge Thomas Rosenberg was quoted in the Daily News yesterday saying that he did not have any recollection of Johnny Lindquist’s case, because he was hearing 60 to 70 such cases a day, Dennis Byrne reports today that Rosenberg “denies earlier reports that he had ordered Johnny taken from his foster parents”. The discrepancy is not addressed.

This heartbreaking picture of Johnny again covers about 25% of the front page.

“[Rosenberg] told The Daily News that the Department of Children and Family Services apparently ‘took it upon themselves to return the child to the parents.’

“Rosenberg said that a representative of the department appeared before him on Feb. 25 and asked for a ‘four to six months’ continuance until a plan could be worked out for the eventual return of Johnny to his natural parents. He said that at that time the next hearing was set for Aug. 4.”

Judge Rosenberg says it’s not illegal for the agency to return children to parents without court permission, but it’s not normal procedure.

Chicago Tribune

by Robert Unger

The Trib’s Robert Unger adds more information from Mrs. Lindquist’s statements to police:

“Johnny couldn’t adjust after being gone so long, Mrs. Lindquist told police. Her husband couldn’t either, she said. He couldn’t understand why Johnny didn’t know them, and it infuriated him to the point of beating Johnny with a metal-lined belt, Mrs. Lindquist said. Then it was fists, Mrs. Lindquist told police, then worse.

“Eventually, it was a plastic clothesline tied to Johnny’s wrists, hanging him over a door for up to nine hours, she told police. He wet his pants, his father argued, and must be punished, Mrs. Lindquist said.

“Last Friday night, it was too much for Johnny. He became hysterical—couldn’t stop crying, His father pulled him into the bathroom and hit him and kicked him, Mrs. Lindquist said.”

“Suddenly, no one seems to know how Johnny’s return to his parents happened.”

August 5, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times

Helen Smith read Eunice Shriver’s article and isn’t having it either. Smith will get her letter into the Daily News too, but next week.

August 5-6, 1972

This is an astonishing day for two young Chicagoans, who get to see their names in the top headline of the Chicago Daily Defender. Nine-year-old Shinette Smith amassed an astonishing 366,200 votes for Queen!

To give you an idea of that accomplishment, Vernon Bey, 7, won King with 78,000 votes—which we would marvel at if not for Shinette’s landslide.

Voting for the King and Queen of the Daily Defender’s 43rd annual Bud Billiken parade began on June 26, and ended July 29. The parade is set for August 12. Rules stipulate that “Contestants must live in the boundaries of the City of Chicago and must be between the ages of 7 and 12 years of age.” How does the voting work? The Defender includes a free coupon in each issue that readers can fill out and return, each worth 100 votes. That means the Defender received 3,662 vote coupons for Shinette Smith.

The Bud Billiken parade grew out of the Defender’s children’s newspaper page, the first of its kind.

On June 24 we saw the first Defender ad urging readers to vote for their favorite contestant, and on July 22-23 we looked at the contestant standings. At that time, Shinette of 6935 S. King Drive led for Queen with 121,900 votes, and Theodis Williams of 2350 S. State led for King with 21,100 votes.

“For weeks now, nearly 200 youngsters from Chicago’s West and South sides have been competing for the titles of Billiken King and Queen and the opportunity to sit on their thrones to greet the hundreds of thousands of people who are expected to be on hand,” writes the Defender today. “Queen Smith is a student at St. Anselm Catholic school and King Bey is enrolled at the University of Chicago Lab School.”

“In addition to all the gifts and prizes that the Bud Billiken King and Queen will receive, they will also have the privilege of riding in the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company’s blimp ‘America,” the Defender reports in another story.

Plus, a few days before the parade, Goodyear “will also use America’s Super

Skytacular night sign which will read ‘Put on a happy face for Bud Billiken Parade King Drive August 12’.”

“More than 7,000 lights, winking and blinking and nodding in a kaleidoscope matching the weirdest of flying saucer tales, are mounted” on signs on each side of the blimp, and each sign is 105 feet long and 24.5 feet high.

“With the America flying 1,000 feet above the ground, the ‘Super Skytacular’ night sign can be read by people on the ground from one mile on either side of the airship.”

“Former all-pro Cleveland Browns fullback turned super film star [Jim Brown] is the newest addition to the personalities in the million-dollar lineup of stars in the 43d annual Bud Billiken Parade,” the Defender further reports today in its headline story.

Jim Brown stars in “Slaughter” opening August 24 downtown at the Roosevelt Theatre. As the Defender notes, Jim Brown had already starred in the classic World War II movie “The Dirty Dozen.”

“Only 11 men in football history have racked up 200 yards or more rushing in a single game,” writes the Defender. “Nobody has done it more than once except Brown, who accomplished the feat four times.”

“Big, dynamic and powerful, Brown is a man of many images. One of his interests is Maverick’s Flat, a Los Angeles discotheque which he owns and where he makes the scene in white satin Dr. Zhivago shirt and love beads.”

“‘I don’t think about my image and I don’t care about it,’ actor Brown said. ‘Images are just that—shadows in the minds of people who don’t even know you. A man and his image are seldom similar.’”

August 5, 1972

Chicago Today: “Movie play in pictures”

This is a regular Chicago Today feature on Fridays, but the point is to show the basic plot of a movie via three pivotal scenes from the film. This week, it’s an excuse to run three pictures in a row of Robert Redford. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

And here’s the ad running for “The Candidate” in all the papers every day this week, another excuse to run a big picture of Robert Redford:

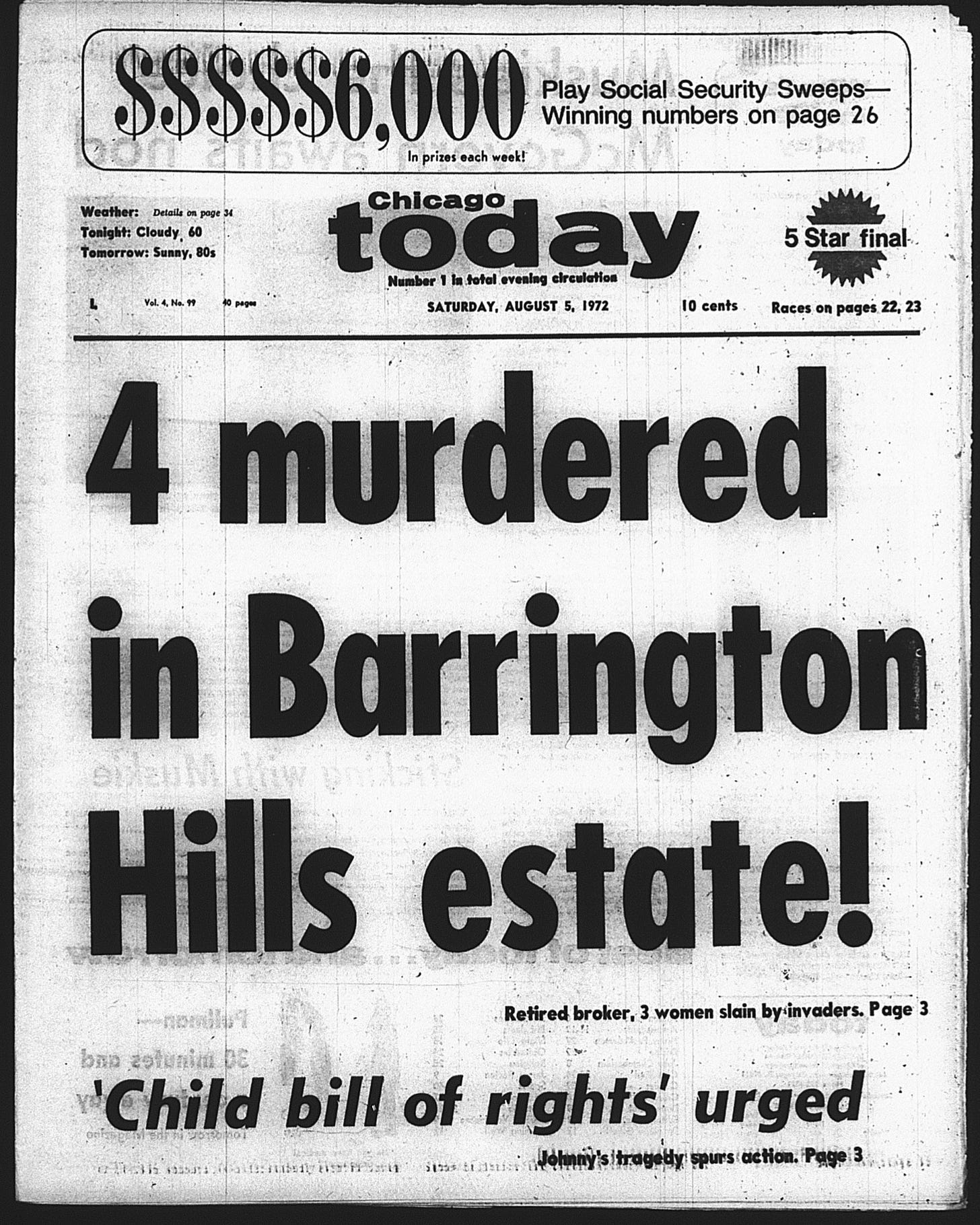

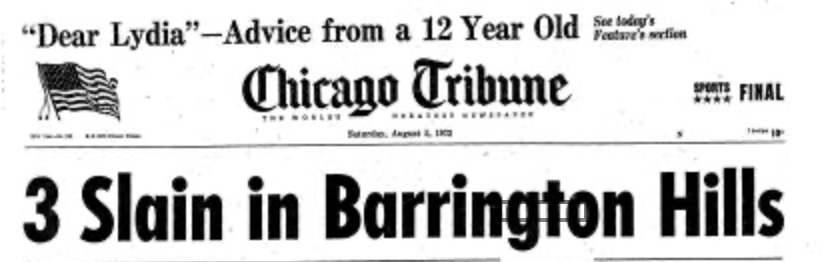

August 5, 1972 and August 5-6: Corbett murders

by Jack Queeney and John Marino

by Edmund J. Rooney and Terry Shaffer

no byline

by Steven Pratt and Philip Watley

And the winner for most sensationalistic lede on the first day of what will prove a truly sensationalistic murder case is…the Tribune! Who knew?

“Three persons were slain and one other critically wounded last night in an exclusive area of Barrington Hills when invaders marched them into a pantry of the home, riddled their bodies with bullets, and left them sprawled on the floor,” write Steven Pratt and Philip Watley.

Inside the pantry, “the invaders opened fire with a .25-caliber automatic pistol and a .30-caliber carbine, leaving the pantry ‘with so many bullet holes we couldn’t count them all.’”

“Paul M. Corbett, 64, and his wife Marion, 57, were found alive in their Bateman Circle home beside the bodies of Mrs. Corbett’s daughter, Barbara S. Boand, 22, and Mrs. Corbett’s sister, Mrs. Dorothy Derry, 60.

“Mrs. Corbett died hours later in Elgin’s Sherman Hospital.”

At press time, Mr. Corbett was in critical condition at the same hospital.

The area was sealed off, roadblocks set up and “a manhunt of the neighboring forests was reported to be underway.” The Chicago Police sent a crime lab unit to help inside the house.

From the Daily News:

“Police said the four were slain during what apparently was a robbery break-in by at least two gunmen.

“‘It looked like a slaughterhouse,’ said Barrington Hills Police Chief Ralph Hummel.

“The gunmen invaded the 14-room home Friday evening and herded the victims into a pantry.

“Hummel said the four ‘were slaughtered without resistance.’”

Each victim was shot at least once in the head.

“It was the worst mass murder in the Chicago area since eight student nurses were slain on the city’s South Side in 1967 by Richard F. Speck.”

The mansion was protected by a burglar alarm, but it wasn’t on.

“We don’t have a damn clue at this point,’ Hummel said.”

The victims were discovered when Anthony Boand, 24, son of Mrs. Corbett and brother of Barbara Boand, arrived at the home about an hour after the murders, at 9:45 PM.

Anthony Boand had borrowed a family car to take his own wife and two children house hunting in the suburb. Luckily, when Boand came back and went inside, his wife and kids stayed in the car.

From Chicago Today: Anthony Boand found the front door ajar and walked in. “The house looked undisturbed, Chief Hummel quoted Anthony as saying, and it wasn’t until a few minutes later that he found his mother and the others lying in the bloody pantry.

The Tribune mentions that Boand told police the small pantry “was flowing with blood.”

“Hummel speculated that the invaders herded the four victims into the pantry and then ‘shot the hell out of them’ before ransacking the upstairs.”

The house, noted Chicago Today, was set back from the road about 50 yards on its 10-acre lot. The Tribune mentioned that it was a two-story gray brick house. The papers all mention the house is “on Bateman Circle” but the precise street address is never mentioned—a bizarre anomaly in 1972, when newspapers include the numbered street address for crime witnesses and random people stopped on the street for a comment.

Anthony went next door to call for help and was still gone when Officer Robert Swenson arrived first on the scene.

“‘The house was well lit with the television set on in the living room,’ Swenson said.”

“Partially filled coffee cups were on the kitchen table, indicating that Mrs. Derry had been paying a social visit to her sister, Marion.

…. “The Corbett's six autos, including a 1923 Rolls-Royce, were still in the attached garage.

“Three shotguns in Corbett’s den were not taken. An inventory of the contents of the home will be made later, police said. They were unable to question Anthony about what was in the home because he was in mild shock.”

Paul Corbett’s wallet was found on a living room table, cash taken but otherwise untouched.

The last murder in Barrington Hills was eight years ago when a real estate broker shot his wife. But just last October, Today recounts, three gunmen entered the Barrington Hills home of the Payes family in the early morning hours and held the family at gunpoint while stealing $200,000 in cash, jewelry and rare coins.

“The bandits, however, were termed considerate and did not harm their victims.”

By the way: I didn’t leave out the Defender’s coverage accidentally, or because their weekend edition wasn’t available. The Defender took a hard pass on this sensational murder story.

We discussed on August 1, with Chicago Today’s first coverage of Johnny Lindquist, that the Defender doesn’t cover murdered, missing or injured white children, unless Black people are directly involved. The Defender didn’t even bother with the dramatic story of 13-year-old Harold Drumm, who got his arm cut off while playing in a trash compactor behind a South Side Zayre, then ran home clutching his sleeve and told his mom, “Mommy, don’t cry. I’ll be all right.” That’s quite a local story to ignore.

The other dailies couldn’t get enough of Harold for two weeks, and they likely got a nice boost in news stand sales with the exciting front pages. The Defender only mentioned Harold a month later, on May 13, and only because an all-Black sixth grade class at Delano School sent Harold sympathy cards, “letters of encouragement and a check for $5.”

Instead, the Defender covers murdered, missing and injured Black children, who are not as well reported in the major dailies. Murdered, missing and hurt Black people/children are no longer all but ignored in the major dailies in 1972, as in earlier decades, but they sure don’t get the same attention.

August 5-6, 1972

Chicago Daily News

The National Urban League’s recent 62nd convention in St. Louis was disrupted by some members of “a militant St. Louis group known as ACTION,” writes Lu Palmer this week.

The ACTION members passed out pamphlets calling the League “an Uncle Tom outfit” and charging that “it always takes sides with white racist institutions against black people.”

“That may be a harsh assessment of the Urban League, but it does express the feelings of many blacks,” writes Palmer. “This distrust…springs from the fact that they are largely financed and controlled by white institutions and to some extent by the government.”

Palmer notes that 28 of the 53 outgoing board members were white, the president of the board was white, two of the four vice presidents were white, the board secretary was white, and so was the assistant secretary. Only four of the nine board officers were Black.

The election, Palmer, writes, “totally changed [the] complexion of the board, which now has 33 blacks and 23 whites. However the dominance of corporate executives was strengthened from 17 to 18. What emerges then is the picture of an organization which is supposed to be in existence to fight the institutional racism that afflicts America but which is under the domination of one of the most racist institutions of all, the awesomely powerful corporate structure.”

The NUL’s budget is about 68% funded by the federal government, he writes, apparently referring to contracts from entities like the Department of Housing, Education and Welfare. That money raises doubts, he writes, “as to whether the League’s priorities are on the side of the masses of black people or on the side of its benefactor, the government, which, like corporate America, is racist in design and function.”

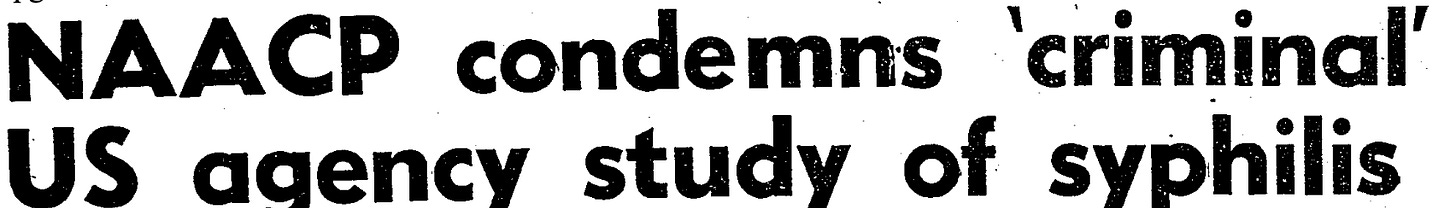

August 5-6, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender

no byline

Gloster B. Current, director of NAACP branches, called for legal action in a statement against “all persons involved in the conduct of the dehumanizing” Tuskegee Study, which was revealed last week initially in an exclusive report from the Associated Press—covered in last week’s TCD1972 on July 25.

“This heinous offense was criminally compounded by the deliberate withholding of curative drugs when they became available,” read the statement, meaning penicillin. “It is further demonstration of how cheaply the conceivers and executors of this diabolic plot hold black life….It is not enough to deplore and suspend it. All perpetrators of this racist crime must be exposed and punished.”

The statement was sent as a telegram to Elliot Richardson, then secretary of Health, Education and Welfare.

The study began in 1932 under assistant surgeon general of the Public Health Service’s venereal disease section, ten years before the discovery that penicillin cured syphilis. As described last week, the study included a cohort of participants with syphilis who were not treated with the drugs available before penicillin, or treated with penicillin after it became available.

At the beginning of 1972, according to this article, “74 of the men were still alive.”

August 5-6, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender: Service Federal Savings ad

August 6, 1972: O’Shea case

Chicago Sun-Times

by Jim Casey

Though a 12-year-old was arrested earlier in the Joseph O’Shea home invasion case, that boy was released from the Audy Home after police arrested three teenagers in the assault.

Police tell the Sun-Times they didn’t think a 12-year-old could have carried out the crime, even though Joseph O’Shea identified him as one of four youths who broke into the O’Shea home at 9311 S. Throop.

“We figured [the 12-year-old] looked like one of the four and that it was a case of mistaken identity,” said investigator Jim Houtsma. Police continued questioning neighborhood teens.

After taking Rodney Mastin, 17, of 9220 S. Ada into custody, Mastin allegedly admitted taking part in the O’Shea raid, claiming he didn’t participate in the beating or arson. Rodney Mastin named two other teens—Phillip Moore, 18, of 9330 S. Aberdeen and Lindsey Smith, 17, of 9200 S. Aberdeen, plus another teen “in the House of Corrections for violation of probation.”

Moore and Smith allegedly admitted trying to set fire to the O’Shea home “to cover their tracks”. Mastin led police to a hiding place with the items taken from the O’Shea home during the invasion—a radio clock and a camera—as well as a saxophone at another location.

“Police Saturday had planned to have a showup at the O’Shea boy’s bedside in Little Company of Mary Hospital, but doctors turned them down because the boy had begun bleeding again.”

August 5-6, 1972

Chicago Daily News, full page ad in Panorama section

In case you were wondering where David Mamet got the idea for “Glengarry Glenn Ross,” Part 1.

August 6, 1972

Chicago Today: full page ad in Chicago Today magazine

In case you were wondering where David Mamet got the idea for “Glengarry Glenn Ross,” Part 2.

August 6, 1972: Corbett murders

Just two front pages for the Barrington Hills murders today because the Daily News only has one weekend edition, and the Sun-Times, incredibly, gave the front page to Sargent Shriver replacing Sen. Tom Eagleton as George McGovern’s Democratic running mate.

Chicago Sun-Times

by Larry Weintraub

Paul Corbett has died of his wounds, completing the slaughter of four family members in a Barrington Hills mansion Friday night.

“Investigators were considering the possibility that the intruders were known to at least one of the victims because the house is fitted with an elaborate burglar-alarm system that is rigged to sound at the Barrington Hills police station.

“No such alarm rang.”

There’s no explanation for why readers were told by all the papers yesterday that burglar alarm wasn’t on—then at the very end of the story, it is noted that the alarm wasn’t set.

“Also the police could find no signs of forcible entry,”

As reported yesterday, the family’s valuable cars including a Rolls-Royce were left behind. The upstairs was ransacked, but “some valuables, notably jewelry, had been left in the bedrooms,” so that Barrington Hills Police Chief Ralph Hummel says they haven’t decided whether the murders were part of a burglary or robbery.

“I don’t know what the hell happened,” said Chief Hummel. “I just know we have four dead bodies.”

Chicago Sun-Times: Michael Miner

by Michael Miner

Reporter Michael Miner, who would go on to become the city’s only press critic for decades in an illustrious career at the Chicago Reader, visits the Corbett house and sets the scene on Saturday, the day after the grisly murders of four family members.

“It is a steep hill up Bateman Circle from its private entrance off Bateman Road and the young girl in jean shorts found herself having to walk her bike up most of the way.

“An older man, apparently her father, had pedaled as far as the first house on the right—a gray brick house set well back in a wooded lawn—and he waited for the girl to catch up. Mosquitoes dropped to his arms.

“‘Is that the house?’ the girl said. ‘I didn’t even know that house was there.’

“The man’s face broke into the grin of one who already knows something that someone else doesn’t.

“‘I think I just stripped my gears,’ the girl said, and bent down to look at the spokes of her 10-speed. The bike was all right, and the two of them pedaled off.”

Miner then takes us back to Friday night, when Anthony Boand, 24, returned to his family’s mansion and found the front door open.

“He had, by all accounts, run screaming from the house, jumped into the green Oldsmobile he was returning to Paul M. Corbett, and raced, horn blaring, back onto Bateman Circle and into the driveway opposite, that of Fred Pollak.

“‘He just kept saying, ‘Hurry up, call the police, something terrible has happened at the Corbett’s house,’ Michele Pollak, 13, recalled Saturday.”

“Fred Pollak sat by his pool Saturday under a red umbrella and slapped at mosquitos. Reporters came down the incline of his side lawn to use the poolside telephone.”

“Pollak thinks someone wanted to kill Paul Corbett. He bases this hunch on the fact that Corbett’s burglar alarm, which rings at the police station, didn’t go off and there was no sign of forced entry. So Pollak thinks it is someone Corbett knew, who wanted him dead.

“Up from Pollak’s pool, along the side of Bateman Circle, a man and a woman on fine brown horses clomped by. ‘It’s a beautiful day, isn’t it?’ the man said.

“If you can’t get away from it on Bateman Circle in Barrington Hills, can you get away from it anywhere?”

Chicago Today

by Leonard Aronson

“As you wind along the blacktop and gravel roads running thru the manicured wilderness of the forest preserves, you’re cautioned by signs to beware of ‘Deer Crossing,’” writes Leonard Aronson in his own atmosphere piece on the murders.

“This is Barrington Hills, the richest, poshest, most picturesque community in the Chicago area—a sprawling, majestic Camelot where persons don’t have homes but estates, and where children grow up feeding not squirrels and alleycats, but horses.

“This is almost a dream. The charms and amenities of rural security and privacy, tinged by just the right amount of natural wildness—only 40 minutes from the bustling diversity, and excitement of the big city.

“It’s a delicately balanced dream, however, and the 2,700 residents of Barrington Hills awakened yesterday to discover it had been shattered by the nightmarish slaughter of four members of one of its most prominent families.”

Aronson goes over the facts of the case, adding that as the assailants ripped the phone out of the wall before forcing the four victims into the 8 x 12 foot pantry where they would be riddled with bullets.

“It is not known whether the Corbett’s two dachsund dogs, Fritzie and Mittzie, tried to protect their masters, but the female was found lying in the living room with the deep gash of a knife in her shoulder.”

“But, however dreamlike its life style may appear to the Chicago area’s other 6.97 million residents, Barrington Hills is still part of the metropolis,” Aronson concludes.

“And it is in the nature of dreams that one must, from time to time, wake up.”

Chicago Tribune

no byline

An unbylined story in the Tribune brings us that most chilling of story archetypes, the one in which we learn how a victim almost avoided a grim fate.

“Mrs. Dorothy Derry didn’t like to drive alone after dark. Friday night that fear trapped her in an encounter with her killer,” starts this Tribune sidebar to other Barrington Hills murder stories.

“That night she turned down a dinner invitation that might have saved her life.”

Mrs. Derry’s husband was fishing in Montana, and she attended a funeral that afternoon for a friend, where other friends invited her to dinner. But Mrs. Derry wanted to drive home while it was still light out.

So instead, Mrs. Derry went home and visited her sister at her beautiful Barrington Hills mansion.

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

I never saw that “cleaned-up” version of the Fritz the Cat poster before. But boy am I familiar with the real one, and here’s the difference: It’s not just that Fritz’s hand is on her breast. It’s that his hand is *down her shirt* and on her breast. And if you know the way Crumb draws breasts, you know that this girl’s underwear drawer was empty. Great post! Thanks for covering this piece of movie history.