THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972: Angela Davis, Hello Charley Girls, and Dick Allen's chili dog

Weekly compilation June 5-11, 1972

To access all website contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 is part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. Follow THIS CRAZY DAY on Twitter, @RoselandChi1972.

June 5, 1972

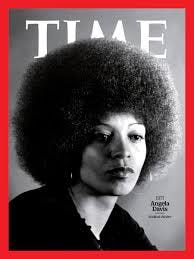

“Chicago’s black leaders Sunday were elated that Angela Davis was found innocent in her controversial California murder-kidnap trial.

“ACLU Attorney Kermit Coleman: ‘I think that the verdict of the Angela Davis jury is a clear indication of simply one more instance of the government filing criminal charges which they never have been able to prove in a court of law for the purpose of inhibiting the freedom to speak, to voice opinions and to disseminate views on sometimes unpopular subjects.”

“San Jose, Calif. — Black militant Angela Davis was found not guilty Sunday of murder, kidnapping and conspiracy in the August, 1970, Marin County Civic Center kidnapping attempt in which a judge was killed and his three abductors fatally shot.”

We’ll use a generous portion of this account since it’s a useful thumbnail for anyone unfamiliar with the Angela Davis trial. The Sun-Times front page reflects the phenomenal national interest in the case. The Berrigan brothers didn’t get this kind of coverage.

“The verdict ended a controversial and costly case that drew worldwide attention and became one of the longest criminal proceedings in California history….by a jury of seven women and five men, 11 of them Anglo-Saxons and one a Mexican-American.

“As the verdict of not guilty on the first count—kidnapping—was read to a hushed and packed courtroom, Miss Davis, 28, bowed her head and began to cry. As the verdicts of not guilty were read on the two remaining counts—murder and conspiracy—the defendants supporter, almost in unison, let out a loud shriek.”

“Later, Miss Davis encountered the jurors who had come to a press room here for a press conference. As they passed by, the defendant embraced and kissed each one. Several…warmly returned the embrace.”

Reporters asked Davis her opinion of the American judicial system. “If you’re trying to imply that I may have changed my opinion, you’re wrong,” said Davis. “The very fact that I was acquitted reveals not that I had a fair trial—because a fair trial would have been no trial at all.”

“Miss Davis was not alleged to have been at the scene of the crime on Aug. 7, 1970, but was charged with murder, kidnapping and conspiracy as a participant in a plot that led to the incident….The prosecution portrayed the Davis case as a simple criminal trial with one of the oldest motives known—love.”

“Miss Davis…delivered her own opening statement. She branded the state’s claims ‘a symptom of the male chauvinism which prevails in this society.’”

“The prosecutor’s theory…was that Miss Davis, madly in love with convict-author George Jackson, conspired with his younger brother Jonathan, 17, to free George from prison….The prosecution charged that Miss Davis had bought four guns and provided them to the kidnappers”.

“The prosecution’s case was circumstantial—in the month before the incident she bought 450 rounds of ammunition and two of the four guns used by the kindappers—including a 12-gauge shotgun, bought Aug. 5, that killed Judge Harold J. Haley.”

“As evidence of motive, the prosecution used excerpts of the letters she wrote George Jackson both before and after the incident in which she pledged her love to him and referred to herself as ‘your wife.’”

“Davis admitted buying the guns, but said she hadn’t knowingly provided them to Jonathan Jackson for the crimes. During the trial, her lawyers attacked the prosecution witnesses who testified they saw her with Jonathan Jackson at San Quentin and a nearby service station.”

June 5, 1972

by John Hillyer

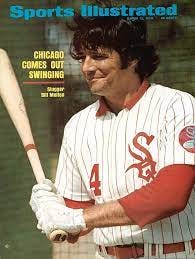

About half the 51,904 paying audience members had left by the second half of the Sox-Yankees doubleheader on June 4, writes Hillyer, when Dick Allen “in his first pinch hit role of the season, stepped into a 1-1 (Sparky) Lyle fast ball and drilled it into the left field seats for a three-run homer in the ninth inning, giving the Sox a 5-4 victory and a double-header sweep.”

But Hillyer lead the article with this irony:

During spring training, White Sox personnel director Roland Hemond “said almost flat-out he would have obtained Sparky Lyle from Boston had Dick Allen’s absence not created a temporary manpower problem.” In other words, Hemond would’ve liked to pass on Allen and take Sparky Lyle instead.

Dick Allen, of course, never ended up attended spring training at all in 1972, so his absence “created a temporary manpower problem” all the way to opening day. Meanwhile, Sparky Lyle went to the Yankees.

But Hemond is probably OK with that now.

“Dick had played every inning of the club’s first 41 games, including yesterday’s 6-1 opener triumph, before becoming the highest paid bench man in Sox history,” writes Hillyer.

“Allen’s one-out shot [No. 9]…lifted the Sox into second place in the American League’s West Division, 3 1/2 games behind Oakland. It boosted Allen’s league-leading runs-batted-in total to 37. It raised the already-incredible Sox home record to 19-3.”

After the game, teammate Mike Andrews gushed awe-struck quotes about Dick Allen to reporters, noting that “Sparky Lyle doesn’t exactly throw lollipops.”

“How do you feel?” Andrews asked Dick Allen.

“‘I feel goo-ood,’ replied the hero,” writes Hillyer.

“Dick, who has been interested in Sox attendance, was told some 11,000 had been turned away at the gates.

“‘Look out, Sox,’ he beamed. ‘I hear ya.’”

Bill Melton kidded Allen that his own home run—during the opening game, with empty bases—went further, “but it went at the wrong time.”

Elsewhere during the afternoon: “A double steal by Allen and [of all people] Melton accounted for a run in the opener. Bill used a nifty move to avoid a tag at second while Dick raced home.”

“The entire supply of 15,000 bats was given away yesterday, plus a reserve of 2,000. After that, youngsters were given gift certificates that may be redeemed for a bat at a later date.”

This June 4th game, and of course the ninth-inning three-run winning home run, is so emblematic of Dick Allen’s arrival in Chicago that it provides the title for the wonderful new biography of Dick Allen by John Owens and David J. Fletcher, edited by George Castle: “Chili Dog MVP: Dick Allen, the 1972 Sox and a Transforming Chicago.”

The book opens with a tight but panoramic look at the Sox and Chicago on that 1972 day, and Dick Allen stepping into the kind of team and fan appreciation he always deserved.

“People were standing on the walkways next to the scoreboard and behind the last rows of grandstands, and sitting in the aisles,” remembered one then-young fan who watched the game from the right centerfield upper deck.

“Unbelievable!” Yankees radio announcer Phil Rizzuto told his audience. “I know it happened ‘cause I can hear that scoreboard going off!”

What’s all that about a chili dog, you’re wondering. As the book explains, that day White Sox clubhouse attendant Jim O’Keefe cooked up a big vat of chili for the players to snack on between games. Out of the line-up for the first time that season, Dick Allen spent much of the second game in the clubhouse whirlpool.

“He was relaxing in there, having a good time, singing, all that stuff,” the book quotes teammate Jay Johnstone, also benched for the second game. “He’s sitting in the whirlpool, buck naked.”

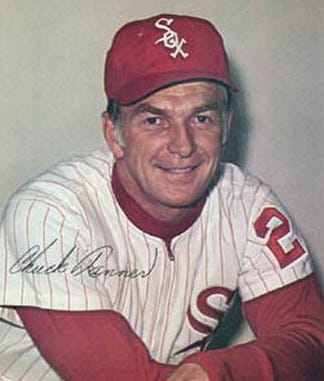

Manager Chuck Tanner finally sent batboy Rory Clark to find his star hitter in the eighth inning.

Clark found him by his locker, partaking in a chili dog that was fashioned from the vat that O’Keefe had left earlier for players in the clubhouse.

“He wasn’t even dressed—he’s in a game jersey and his shower shoes,” Clark remembered. “And I said, ‘Dick, Chuck wants you to pinch hit.’ And he looked at me like I was a Martian. He said, ‘Tell him I’m eating a chili dog.’ And I said I’m not going to tell him that. So, he had spilled chili all over his front, right? So he had to get out of that.”

And so Dick Allen, fresh from the whirlpool and chili dog, ended up at the plate with his 40-ounce bat in the ninth inning with the Yankees leading 4-2 and the fans already on their feet as if everyone knew what was going to happen.

“Despite the low trajectory, Yankees left fielder Roy White knew the ball was gone the moment it was hit, and he headed off the field almost immediately…. Sparky Lyle didn’t bother to watch; neither did Yankees third baseman Hal Lanier.”

Since this home run is such a seminal event in White Sox history—and to White Sox fan Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the novel at the heart of this Substack, who was ten years old in 1972—we’ll look at a little more coverage before moving on to the rest of the week’s news.

“One year ago, after their 42nd game, the Chicago White Sox had a record of 17-25.

“Today, they’re 25-17. That’s an eight-game shift.

“One year ago, the Sox didn’t win their 25th game until June 22 [their 63rd game]. By then, they’d lost 38.

“These simple statistics are offered for those impatient fans who want success so badly they may not recognize what they’re seeing.”

Along with that improvement, notes Talley, comes the audience.

“You had to be impressed with yesterday’s crowd of 51,904 for the double header against the so-so Yankees. Largest in 18 years and sixth largest in Sox history. And note the three-game series total of 114,847, largest since 1961 and I wonder what happened to that so-called bad neighborhood?

“Will this be the year the Sox outdraw the Cubs? Why not?”

Talley’s closer: “One request. Don’t call me for tickets to the first Cubs-Sox World Series since 1906. Not unless Leo gives me some of his allotment.”

by Jerome Holtzman

“It’s between games of Sunday’s White Sox-Yankee doubleheader and manager Chuck Tanner is in his clubhouse office, waiting for Game 2. The phone rings. John Allyn, the owner, is calling. He has seen the second-game lineup and he asks: ‘Why isn’t Richie Allen playing in the second game?’”

“Tanner puffed on his victory cigar and said with a smile, ‘Well, Mr. Allyn, I’m giving Richie a rest. He’s played every inning of every game. He hasn’t said so but I know he’s tired.’

“Tanner makes a prediction: ‘Don’t worry, Mr. Allyn. I’ll use him in the ninth inning. He’ll come up and hit a game-winning homer.’”

Holtzman describes the scene after Allen’s homer won the second game:

“The fans, the 15,000 or so still in the park, are on their feet cheering. So are the White Sox players. It’s a World Series photograph. Richie’s teammates rush out and line up along the third-base line. They want to shake his hand, pat him on the shoulder, leap on his back—anything.”

At the lockers, Allen tells reporters that teammate Pat Kelly predicted he’d hit a three-run homer.

“‘That’s right, homey,’ Kelly replies.”

“Tanner receives another call. He answers the phone. ‘Yes, Mr. Allyn, that’s what I said. He’d hit a game-winning homer in the ninth.’”

Reporters pepper Allen with questions.

“Is it tough coming off the bench hold? What did you do to warm up?

“Richie smiles.

“‘It’s like chopping down a tree. You don’t warm up. You just do it.’”

June 5, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times: Tom Fitzpatrick column

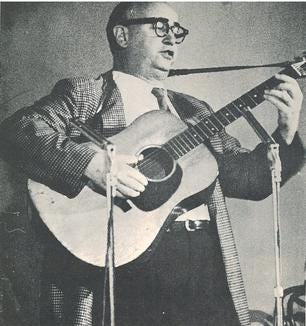

Independent Democrat Ald. Bill Singer (43rd), now in the middle of his second term, holds a tent party for the third year to fund his ward office. Folk singer Win Stracke is the main attraction.

“Win Stracke shouted down to Singer now from his place on the platform,” writes Tom Fitzpatrick in his “Fitz” column.

“‘What are the new boundaries of the ward, Bill?’

“Singer shouted back that they were from Wellington to Division on the south and from the lake to Southport on the west. That was all Stracke needed to begin a parody of ‘This Land Is My Land,’ starting out with ‘This ward is your ward.’”

Win Stracke, by the way, co-founded the Old Town School of Folk Music.

“It’s ironic that Singer’s new brand of politics should take hold in the very ward that, under the leadership of Mathias (Paddy) Bauler, used to symbolize the old politics,” writes Fitz.

“We all love Paddy, who was the last of the saloon-owning aldermen. Who will ever forget the famous picture of Paddy doing a jig on the City Hall steps the day Mayor Daley was first elected and shouting: ‘See what I said. Chicago ain’t ready for reform yet!’”

Fitz notes that Chicago still isn’t ready for reform, but “Singer is engaged in one of the most meaningful battles” right now: “an attempt to unseat the slate of 59 ‘uncommitted’ Democrats to the national convention in Miami Beach. If Singer and his group win that fight it could be the most important story to come out of the Democratic convention.”

Fitz illustrates the difference between Singer and the old ways with another Paddy Bauler anecdote: While Ald. Singer pays his parking tickets rather than fixing them, Paddy Bauler was once confronted by a cop telling him to shut his saloon doors at the legal closing time.

“Paddy ended up shooting the policeman, who was later fired for his efforts. Times change.”

June 5, 1972

Chicago Daily News

by Robert Herguth

“A 100-year-old male tradition vanished like a shot Monday morning in the Palmer House,” writes Herguth.

“A pretty farm girl from Iowa began work as the hotel’s first lady bartender.

“One hardened customer said this affected him not at all, except he might double his tip.”

Jan Koenen, 23, is from Alexander, Iowa and wearing “a silver something-or other” as she tends bar in the Palmer House’s “Den” after working there as a cocktail waitress. If she measures up, they may move her to one of the other hotel bars “to see if she stirs up business there.”

June 5, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender

Stephen Gates, the 19-year-old who stood in front of Adler & Sullivan’s Carson, Pirie & Scott store at State and Madison at midnight on May 22 before walking into the street and setting himself on fire, died at Cook County after suffering burns over 75% of his body.

See May 24 here for the full story.

“While no apparent motive was established for the tragedy, Area One Homicide Investigator William Savage told reporters that an undisclosed note found in the youth’s car referred to an undisclosed personal problem that had been troubling him.”

If you’re a regular THIS CRAZY DAY reader, you’ll probably want to follow Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today too.

June 6, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times

After facingChicagoans all over the city in community meetings following charges of police brutality by U.S. Rep. Ralph Metcalfe’s Concerned Citizens for Police Reform, Police Supt. James Conlisk faces aldermen in City Council hearings.

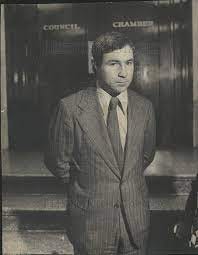

Independent Democrat Ald. Dick Simpson (44th), always a thorn in the Daley administration’s side, takes the lead— “but he succeeded only in getting Conlisk to say that he was studying the possibility of establishing civilian review boards in the city’s 21 police districts,” writes Harry Golden, then the dean of City Hall reporters.

Metcalfe and his allies aren’t there—these hearings were called by Mayor Daley stalwart Ald. Claude Holman (4th) “after the Council voted down a resolution asking Daley and Conlisk to meet with Metcalfe, who has demanded such a meeting.”

Guess who ran the hearing? Ald. Edward Burke, who is still alderman of the 14th ward in 2022—the longest-serving alderman in Chicago history, having taken over his dad’s seat in the Council in 1969.

Burke is still relatively green in 1972, just three years in office, but already chairman of the police committee and ready for anything. In 1983, Burke would ascend to the all-powerful position of Finance Committee chair during Mayor Harold Washington’s first term, lose the position for two years after Mayor Washington wrested control of the Council, and bounce back to Finance with new Mayor Richard M. Daley in 1989. Burke would stay at Finance for 30 years, until he finally got indicted in 2019.

In 2022, Burke faces 14 counts of all the big usual charges—racketeering, attempted extortion, yada yada yada. The charges include Burke’s alleged attempts to extort money from a Burger King in his ward, and to get his law firm hired by the New York developers of Chicago’s old main Post Office.

Ald. Simpson wanted to know if Supt. Conlisk approved of Rep. Metcalfe’s proposal for a civilian police review board in each police district.

“Burke interjected that Conlisk was not prepared to answer, and Simpson said, ‘I ask you again—do you support civilian review at the district level?’”

But Conlisk would only say that it’s under review.

Ald. Edward Vrdolyak (10th), soon to be known as “Fast Eddie” to the entire city, pointed out in his own “questioning” of Conlisk that there are about 3.8 million arrests every year—so 980 brutality complaints is only three charges for every 13,000 arrests.

Chicago Today

by Michael Garrett

More from Ald. Dick Simpson during the Council’s police hearings:

“What we have to do is convince enough people that the long-standing American principle of civilian control over the military should apply here. The citizen should control the policeman as he does the soldier.”

Simpson predicts the hearings could “stretch out for months. And I think they should.”

But Ald. Burke says the hearings will end tomorrow. That’s in the Daily News coverage, next item. Tomorrow’s Chicago Today will report that Ald. Burke “adjourned [the police brutality hearings] yesterday after two days without noting when or if they would resume.”

Chicago Daily News

by Jay McMullen

Despite Ald. Simpson’s belief that the police hearings would last for weeks, Jay McMullen reports that committee chairman Ald. Burke says the hearings will end tomorrow.

The Daily News account includes Tuesday testimony by officials from several police fraternal groups.

“John Dineen, president of the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge No. 7, charged that only criminals would benefit from [a civilian review board] by learning through open hearings what evidence police had against them.

“‘The people who will suffer will be the people of Chicago because criminals will be walking the streets free,’ Dineen said.”

Harold R. Herrick of Chicago Crime Fighter Local No. 1 said, “I expect to be treated with dignity and respect. But when I deal with scum, I have to treat them like scum. Please don’t put the handcuffs on us by creating a civilian review board.”

June 6, 1972

Chicago Tribune: Clarence Petersen column

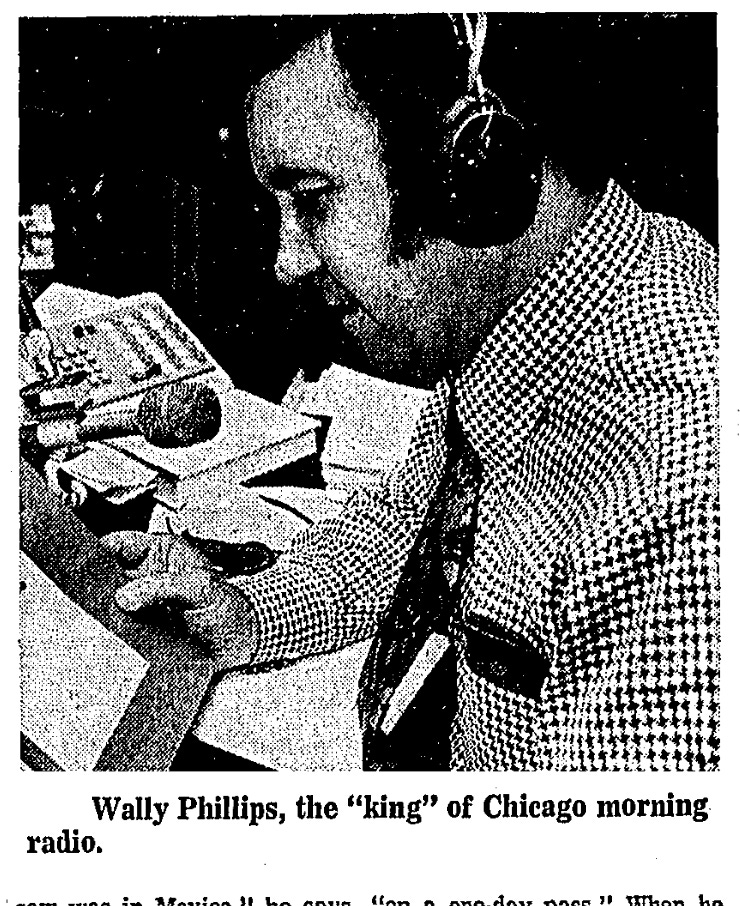

After 18 years at WGN, Wally Phillips is the undisputed king of morning radio, writes Trib radio/TV columnist Clarence Petersen. Wally’s parents enrolled him in a seminary to become a monk, but it didn’t work out.

Instead of “living alone in a cell with no phone,” writes Petersen, “Phillips has done more with the phone than anyone else since Alexander Graham Bell. He once called Ipanema to find out if they really did have a girl down there who was ‘tall and tan and young and lovely,’ as the song said.”

At WGN, Wally started by teaming up for television with Bob Bell, who would go on to fame and a lot of make-up as the Bozo in “Bozo’s Circus.” But “a series of flops” on TV sent Wally to radio.

“‘I have a dream, temporarily unrealistic,’ Phillips once told me,” writes Petersen. “‘I’m sitting in a studio with 400 telephones and six secretaries so that if anything happens anywhere in the world I can just push a button and find out all about it.’”

Right now, Wally has six phone lines in his studio and one producer, Marilyn Miller, “who works from predawn till late afternoon or early evening, screening calls that come in during the show and setting up calls for the next day. Phillips does not just up and call Mayor or Mrs. Daley…such calls are arranged in advance.”

Wally is “a newsman more than anything else” and he “has the largest broadcast news staff in Chicago: his listeners. They are everywhere, and whenever they see something unusual, they call, and Phillips puts them on the air.”

And, Petersen notes, Wally and his listeners love a good cause.

“The most recent was a fund-raising campaign for Harold Drumm, a 13-year-old Chicago boy whose severed arm doctors were attempting to restore. It happened the day before the Oscar awards were presented in Hollywood, and the next morning Phillips asked the Tribune’s Norma Lee Browning for a few Oscar mementos and autographs that he could auction off on the air for the Harold Drumm Fund.

“Miss Browning got almost everyone in Hollywood to contribute something. Zsa Zsa Gabor contributed a nightgown which went for $225. Charlie Chaplin’s autograph brought $1,500.”

“To Phillips, the news, the exchanges of information, and the charities all add up to one thing: ‘People helping people—that’s what radio is all about.’”

Harold lost the fight to save his arm just last week. For more details, see April 9 and April 11 here. Harold’s accident was a drama that captured the city’s imagination after the brave boy ran home three blocks, clutching his empty sleeve, and told Mrs. Peggy Drumm, “Mommy, don’t cry. I’ll be all right.”

June 6, 1972

All the major dailies weigh in on Angela Davis on June 6, and the Defender follows the next day—along with Charlie Cherokee. Excerpts from each:

Chicago Today

“Angela Davis’ acquittal on all charges was surprising—nearly as surprising as the exact opposite outcome would have been….But the state’s case, tho unsatisfactory to the jurors, was by no means as tenuous as the defense attorneys and Miss Davis herself says it was.”

“Some facts tend to get lost…There was a shooting during an escape attempt at the Marin County courthouse….Four persons, including a judge and a prisoner with whom Miss Davis was admittedly in love were killed, and the guns used in the attempt were registered in Miss Davis’ name.

“Miss Davis was held on charges based on these facts, not on her politics….Yet in claiming that she shouldn’t have been tried at all, Miss Davis implies that political persuasion should in some cases—notably hers—provide immunity from the ordinary workings of justice. That is as silly as arguing that white racists in the south should be immune from suspicion in crimes with black victims.”

Chicago Sun-Times

“There were three highly publicized earlier trials—of Dr. Benjamin Spock and others in Boston, of the Chicago Seven conspiracy and of the Rev. Philip F. Berrigan and others in Harrisburg. In all of these, the fact that the defendants held unorthodox political views…outweighed in the public mind the exact and narrow points in the criminal indictments for the trials.

“To the extent that this was part of the trial of Angela Davis, it was deplorable, but it points up what happens when federal and state prosecutors create a political climate in criminal trials. If attorneys general of the United States and the various states would cease and desist from panting after political convictions, greater justice would be done because defendants would be brought to trial strictly on the merits of the individual charges against them.”

Chicago Daily News

“….Angela Davis said that her acquittal… ‘doesn’t mean I’ve had a fair trial. A fair trial would have been no trial at all.’

“….Miss Davis is less fair to American justice than American justice was to her.

“….The question of guilt or innocence finally came down to the question of which set of witnesses the jury found more credible. The jury believed the defense’s witnesses, and voted acquittal.”

“The outcome does not prove, of course, that any black can get a fair trial anywhere in the United States….But it seems to us that this trial…provides important evidence that blacks can, and increasingly do, find justice in the American courts.”

Chicago Tribune

“Well, Angela Davis has had a first hand taste of American justice. As a result, she is a free woman, acquitted of charges of murder, kidnaping, and conspiracy—and free to continue denouncing the United States as a land of oppression, corruption, and injustice.”

“We cannot quarrel with the verdict….but it is hardly an argument for adoption of the Communist system, where people are jailed incommunicado for months without even being charged with anything, and where, if even a secret trial cannot serve the government’s purpose, a defendant is simply declared insane and salted away without any trial at all.”

June 7, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender: editorial

“The not-guilty verdict by an all-white jury in the celebrated Angela Davis case is a victory that transcends the ordinary bounds of legal pleading. To be sure, it was a welcome victory for a black woman whose fate was in the hands of a lily white panel.”

“However, in the perspective of contemporary history, the verdict is a triumph of the American jury system….There was much apprehension among liberals of both races that Angela’s Marxist dialectic would mitigate much against her….and that she was being prosecuted more for her politics than for her presumed guilt.

“The jury’s findings invalidate these assumptions….The American jury system achieved golden heights in the Angela Davis case.”

June 7, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender

Yes Younger Readers, the Defender ran a column named “Charlie Cherokee Says,” starting in the 1940s.

Meet Steve Bertolucci, hero of the novel central to this Substack, as he walks to work in the IBM Building in 2003 and learns the mystery behind the new conference room windows.

June 8, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Letters to the Editor

See here for Mike Royko’s take on President Nixon’s recent gift to Brezhnev during his historic trip to the Soviet Union.

June 8, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender

The Phone Company. It’s everywhere. I don’t include these, but Chicago Today’s Action Line, a public service column, devotes about 10% of its letters to getting the phone company off its readers’ backs for alleged long distance calls and other phone bill disputes.

June 9, 1972

Chicago Daily News

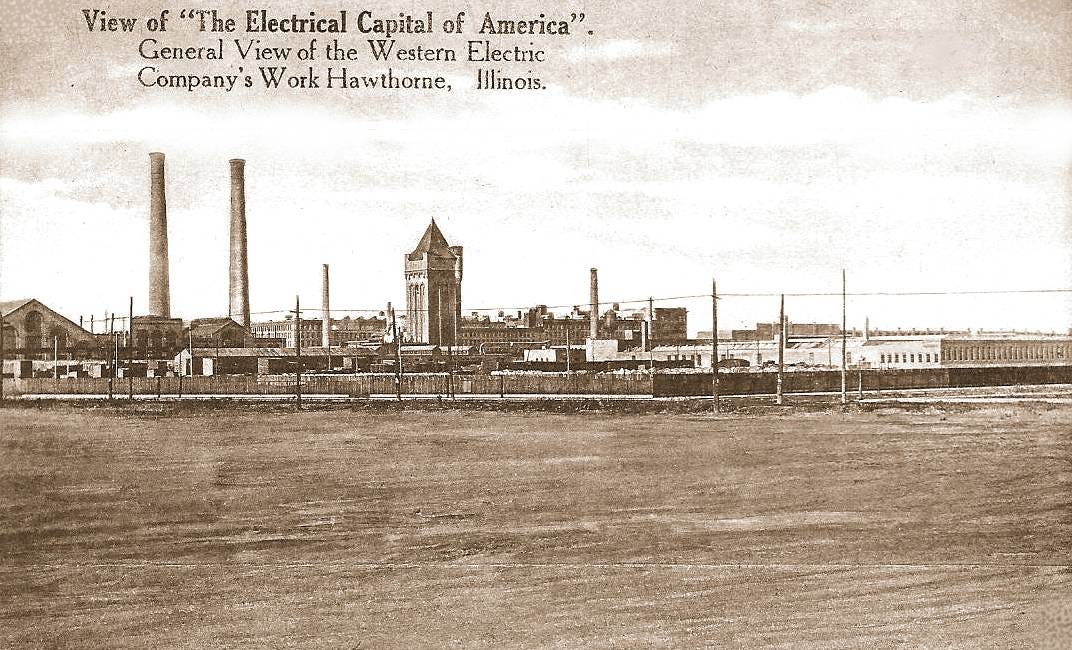

Every year, Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works factory at 24th and Cicero crowns a “Hello Charley Girl” and accompanying court. Traditionally, they “represent the company’s employees at social and service activities,” notes the Daily News.

This year, it’s Katie Cominsky, 19.

“About 300 employees gathered in the warm sunshine at the plant…to watch Miss Cominsky receive her crown. She was elected from ten finalists in balloting by 16,000 Western Electric employees in the 41st annual contest.”

Cominsky is a service clerk at Western Electric’s Western Avenue shop. The Hello Charley Girl’s picture is emblazoned on a decal for car windows, distributed to all Western Electric employees nationwide.

The Tribune covered the crowning of Hello Charley Girl nearly every year. “The ‘Hello Charley’ girl’s title is derived from the traditional greeting exchanged by vacationing Western Electric employes when they meet on their travels,” the Trib explained in 1946. “The stickers provide an easy means of recognition among motorists.”

Hello Charley Girls through the years:

As I collected the photos for the collage above, I realized something: Katie Cominsky was the last Hello Charley Girl.

She wouldn’t have known it at the time. The end of the Hello Charley Girl was not announced, at least not in a way that drew coverage from the Tribune and the Daily News, as Charley Girls had done since at least 1935—their first appearance in the Tribune, when the contest was in its fourth year.

Not having access to a Hawthorne Works employee newsletter, we can only imagine if the Hello Charley Girl concept was widely debated, or just quietly retired by executives who sensed which way the Women’s Lib wind was blowing.

It’s funny: The end of the Hello Charley Girl was one small part in the wonderful progress women were making in 1972. But the end of the Hello Charley Girl still feels sad. I picked this item to make fun of crowning events—retrograde activities that they were, and generally still are. But does a crowning event have to be entirely retrograde and sexist in every instance, before or now? Well, of course not. Sometimes it can just be fun. Having looked into Hello Charley Girls now, it’s not like they had to prance across stage in a bathing suit, or pose for nude centerfolds in Playboy, or let Donald Trump walk around their dressing room while they were in their underwear.

It’s too bad that what appears to be a sweet tradition couldn’t have been expanded into Hello Charley Chums or something. Admittedly, it wasn’t going to last much longer anyway, as you’ll see below.

Western Electric was a massive 20th century Chicago employer, though Younger Readers will almost certainly not know the name at all.

The company officially started in 1872 after moving to Chicago from a small Cleveland workshop established by partners Enos Barton and Elisha Gray, per the company’s website. The Encyclopedia of Chicago says Western Electric started here at Kinzie and State Street, moving to a factory at Clinton and Van Buren by 1900 and employing 5,300 workers.

“In 1904, when annual sales neared $32 million, the company relocated to suburban Cicero, where it had built a large new manufacturing complex known as Hawthorne Works,” writes the Encyclopedia. “By 1917, this facility employed 25,000 people…making it one of the largest manufacturing plants in the world.”

Western Electric started out manufacturing electric components for companies like Western Union. By 1881, Western Electric had annual sales of $1 million when it was bought by American Bell. As all Older Readers know, American Bell became AT&T.

That means The Phone Company, so Western Electric is/was pretty darn big. Just ask the reporters who work on “Action Line.”

Soon Western Electric invented vacuum tubes. And condenser microphones. As movies raced to add sound, Western Electric came up with systems like “Vitaphone.”

Then in 1947, Bell Laboratories invented the transistor. That means Western Electric is directly responsible for all the transistor radios still rattling around the world, including the cool ones that looked like packs of cigarettes.

“Ben-Hur”’s 11 Oscar wins in 1959 included best sound, which came from a Western Electric sound system called “Westrex.”

In 1962, Bell Labs invented the electret condenser microphone. Per the company’s website, “The vast majority of microphones used today are electrets.”

Wikipedia says Western Electric ceased to exist in 1995, but Western Electric thinks it exists enough to maintain a very nice website.

Either way, Hawthorne Works shut down in 1986, not long after the federal government broke up The Phone Company.

The always fascinating Chicagology website devotes a detailed section to Hawthorne Works with views of the main entrance, the foundry, the machine shop, water tower, interior shots of the machine shop and assembly floor, and some sweeping overviews of the entire plant.

Chicagology also explains the plant’s name: “Hawthorne” was the original name of the town that became Cicero. I did not know that.

Finally, Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works has a rather huge Chicago history connection: In 1915, the company chartered several ships to take Hawthorne Works employees to the annual company picnic being held that year in Michigan City, departing from the south bank of the Chicago River between Clark and La Salle.

One of those ships was the SS Eastland.

“Early on the morning of Saturday, July 24, 1915, a light rain fell,” writes the Eastland Disaster Historical Society. “The air was filled with anticipation and excitement. Thousands gathered along the Chicago River for Western Electric’s fifth annual employee picnic. More than 7,000 tickets had been purchased for the day-long festivities.”

The maximum capacity of 2,572 passengers had boarded the SS Eastland by a little past 7 a.m. But the ship never left its place at the dock.

“Tragedy struck as the ship rolled over into the river at the wharf’s edge….844 people lost their lives, including 22 families.”

The Eastland tragedy is considered the single largest disaster in Chicago’s history due to its appalling death toll. Fatalities from the Chicago Fire are typically set at 300, while the Iroquois Theatre fire killed 602. A fascinating 2014 Smithsonian article notes in its title: “The Eastland disaster killed more passengers than the Titanic and Lusitania. Why has it been forgotten?”

By the way: 20-year-old George Halas was supposed to board the Eastland that day, but he arrived late. Good thing he wasn’t running on Lombardi time.

June 10, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender: Letter to the editor

But before we get to the letter:

Why has the Defender gone to the trouble of typesetting a special disclaimer for a letter to the editor?

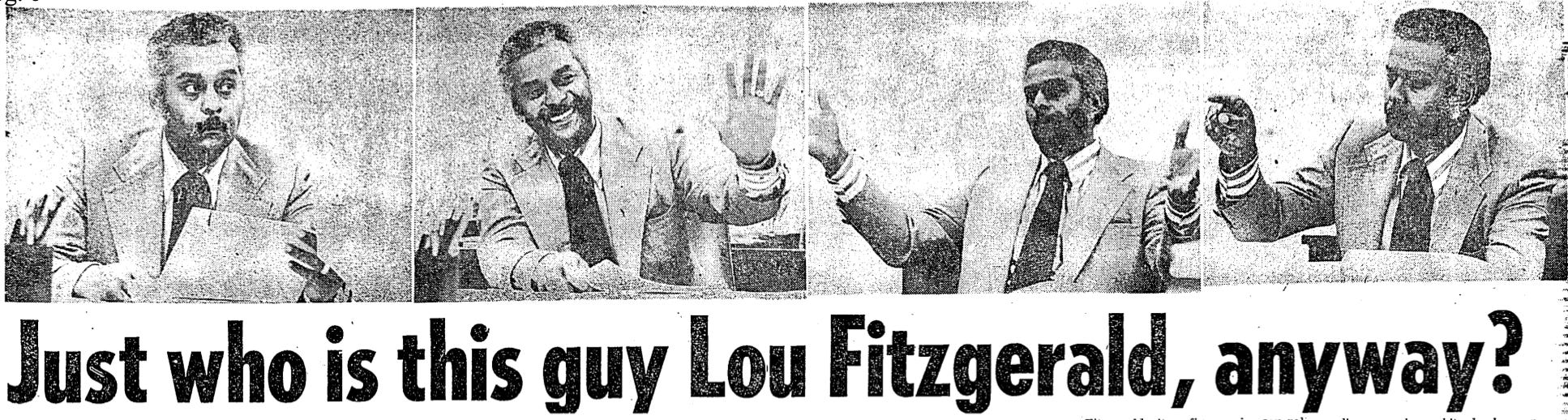

Because Louis Fitzgerald writes some truly trenchant “letters.” Even Older Readers may be surprised by Fitzgerald’s missives—and that the Defender prints them.

In a November 1972 profile, the Defender’s Robert McClory will write: “Any regular reader of the Daily Defender who doesn’t have an opinion about Louis A. Fitzgerald just doesn’t know what’s happening!”

Note: McClory doesn’t normally write with exclamation points. And yes, the Defender ran a lengthy profile about someone who writes letters to the paper.

“Fitzgerald’s articles, which appear several times a month, probably draw more comment (mostly critical) than those of all our other columnists put together,” writes McClory. “He has been called ‘the worst honky-defending, Uncle Tom ****** who ever walked the streets of Chicago.’”

Note: The Defender always prints the entire word, no asterisks. In this one regard we cater here to 2022 sensibilities rather than make everything about one word instead of one year, 1972.

“But he also regularly receives letters and calls of enthusiastic praise from other black readers,” McClory continues. “‘Thank God, thank God for Louis Fitzgerald,’ said one woman last week. ‘Here is a man who tells it like it is.’”

Fitzgerald began writing to the Defender in January. By June, Louis Fitzgerald is a bona fide 1972 phenomenon in the paper who can’t be ignored. The letters column becomes an ongoing referendum on Louis Fitzgerald.

McClory notes that most of the letters received by the Defender rip Louis Fitzgerald to shreds. We can’t really know how representative the letters are of the Defender’s readership, since most people write to newspapers when they’re angry. But we know without doubt that Louis Fitzgerald makes many readers furious.

Even journalist Warner Saunders, still in the early years of his long Chicago TV career (Ch. 2 and then Ch. 5) devoted one of his semi-regular “My Bag” columns in the Defender to answering Louis Fitzgerald back in March.

So what’s with that disclaimer? The Defender clearly enjoys the talk and attention Louis Fitzgerald’s letters create, but isn’t ready to take responsibility for him—even though his letters grow to the length of short articles by February, and by March the letters are printed outside the letters section as columns with headers like “One man’s view” or just “Opinion.” By September, the Defender will refer to Fitzgerald as a “guest columnist” in an editorial explaining why they publish his writing. By early 1973, Louis Fitzgerald is officially called a Defender columnist—with a picture.

The September editorial notes that the Defender doesn’t always agree with Fitzgerald—but makes it clear that the paper’s leadership feels Fitzgerald brings something crucial to the table: “a lonely voice, calling for a badly needed dose of critical self-appraisal while urging black pride to grow up to the fill dimension of its responsibilities.”

Fitzgerald stopped writing his column in 1984, with no official announcement that I can find in the Defender archives. By then, he’d become a radio staple, including hosting shows on WVON and a weekly Saturday night show on WIND.

Oddly, I couldn’t find an obituary for Fitzgerald in any of the papers, including the Defender, which must be due to some hiccup in the Defender digital archive. He’s not included on the valuable History Makers website. Still, as of April 2022, Honore from 84th to 86th is Honorary Louis Albert Fitzgerald, Jr. Way.

We’ll be hearing more from Louis Fitzgerald, because the Defender wants its readers to hear his views. So let’s get to know him. We’ll crib largely from McClory’s fine profile.

Louis Fitzgerald, Jr. was born January 26, 1929 on the South Side, orphaned at 10, and moved through foster homes “with stops” at the Audy Home as a teenager before joining the Army. He earned a college degree while stationed in Japan, and ended up in Chatham when he came home to Chicago.

Louis Fitzgerald’s first appearance in the Defender is March 20, 1961, as chairman of the Chatham Avalon Park Community Council’s Emergency Relief organization. The group helped 60 families affected by a tornado that touched down in the neighborhood. At that time, Fitzgerald lived at 8211 S. Michigan, a handsome red brick courtyard apartment building, then and now surrounded by blocks of tidy bungalows.

“In 1962, he persuaded WBBM-TV to do a documentary on racial change in Chatham (entitled ‘Decision on 83rd St.’) and wrote the story outline himself,” wrote McClory. “From there, he went on to become the first black account executive for WMAQ-TV, before going into government work.” According to Fitzgerald’s honorary street sign designation, he was regional director of the Midwest Division for the U.S. Department of Labor.

In 1972, McClory and readers couldn’t watch “Decision on 83rd St” on YouTube, but we can—see the embedded link below. The documentary, reported by Hugh Hill and about 36 minutes long, looks at the Marynook enclave, where many blocks were developed in 1955-56 as nearby Chatham underwent rapid white flight.

In 1962, as the cameras roll, Marynook is beginning to integrate. One white Marynook couple describes the constant phone calls they get from panic peddling real estate developers trying to get them to sell. The second Black couple to move in reports they were well-received in the initially all-white community. This is an amazing time capsule look at a South Side neighborhood when many residents really believed they could buck the re-segregating trend around them.

It’s also a look at Chatham, where Hugh Hill says some white residents stayed and some moved back after seeing that the neighborhood remained stable. After a look at early panic-peddling in Chatham, Hugh Hill says, “But now the days of panic and flight are over. The community belongs for the most part to Negroes, and they are struggling just as their predecessors did to maintain high standards in the area.”

Louis Fitzgerald enters at the 17:08 mark, walking down his street with Hugh Hill. He says whites who drive through Chatham are probably shocked that it hasn’t turned into a slum, and they might be sorry they left.

“I think that they have been brainwashed to a certain degree that all Negroes live in slum conditions…If they could see this I think their minds would change a little bit,” says Fitzgerald.

A young white couple who stayed in Chatham describe how they “exchange baby-sitting favors” and live with their Black neighbors.

“Do you think an integrated community in Chicago, truly integrated, can be successful?” Hugh Hill asks.

“I don’t see any reason why it should not be successful,” answers the wife. “Human beings are generally the same.”

Fitzgerald drives with Hugh Hill down 79th street and talks about struggling to retain businesses, and the problems with too many bars and liquor stores. As McClory notes in his profile, Fitzgerald’s Chatham-Avalon Community Organization “spearheaded the biggest local option in Chicago history when it voted 10 precincts dry in 1958.”

Fitzgerald tells McClory he made the documentary “because I wanted to show the public that a changing neighborhood doesn’t have to become a slum.” Chatham is a well-kept neighborhood, but Fitzgerald says it’s not typical, “and that’s what burns him up….He agrees that America is a racist country and that racism is the ultimate case of black problems. But Fitzgerald feels black leaders spend too much time ranting about ultimate causes (‘which can’t be changed very quickly’) and not enough about proximate causes (‘which can change if people just get off their rears’).”

Fitzgerald thinks the city doesn’t provide equal services for Black wards, but says, “It’s got nothing to do with racism. The politicians don’t give a damn what we say because they know we won’t exercise united opposition against them where it hurts—in the ballot box….We’ve been so brainwashed to think the system won’t work for us that we prevent it from working for us.”

Fitzgerald pops up in the Defender in a 1971 article that gives plenty of insight into his future letters and columns:

In 1972, when he talks to Robert McClory, Louis Fitzgerald is “a soft-spoken, articulate, Southside black man of 43. He has spent most of his adult life in Chatham, although he recently bought a home in North Beverly. He has a black wife, two married daughters and a 20-month old son.”

On Monday, the Defender ran its second column-length “letter” from Louis Fitzgerald, the provocatively headlined “Why must blacks act like animals?” “The actions by some blacks in the downtown area of Chicago is downright disgusting if not outright ignorant,” reads his lede.

Further down: “Blacks who would like to live decently are running away from blacks just as whites have been and are doing. It is not difficult to understand why blacks, too, are running…Stable businesses are moving and relocating to other areas because of threats, robberies, broken windows and the like….No one can tell me we have been programmed to be destructive….While we cry for equality on one hand we exert inequality by being destructive!”

Now, today’s letter/column from Louis Fitzgerald:

“There should not be any black folks in hell and every angel in heaven should be black because while we blacks are supposed to be blessed with rhythm we certainly are blessed with religion,” writes Louis Fitzgerald.

It’s understandable that churches have been a social focal point for Black people, he writes, “since our movement sociably was confined….Churches have been a staple of hope for our people and hopefully they will continue to be….The home is foundationless unless there is love and a belief in a supreme being.”

“But, and this is a big ‘but’ we all cannot have the calling. We cannot all be preachers, ‘but’ if you look around you, you will find the storefront churches are doing a bang-up business. In some areas churches are stacked up on top of each other with five or six in a row all espousing their method of getting into heaven.”

The preachers drive away after services, writes Fitzgerald, “in their ‘deuce-and-a-quarters’ and the parishioners catch the bus.”

Fitzgerald figures most storefront preachers are unordained and bilk “the unsuspecting out of their nickel and dime contributions…Church and religion have become big business, black and white….Storefronts in a stable community have a deteriorating effect whether we want to accept this or not.”

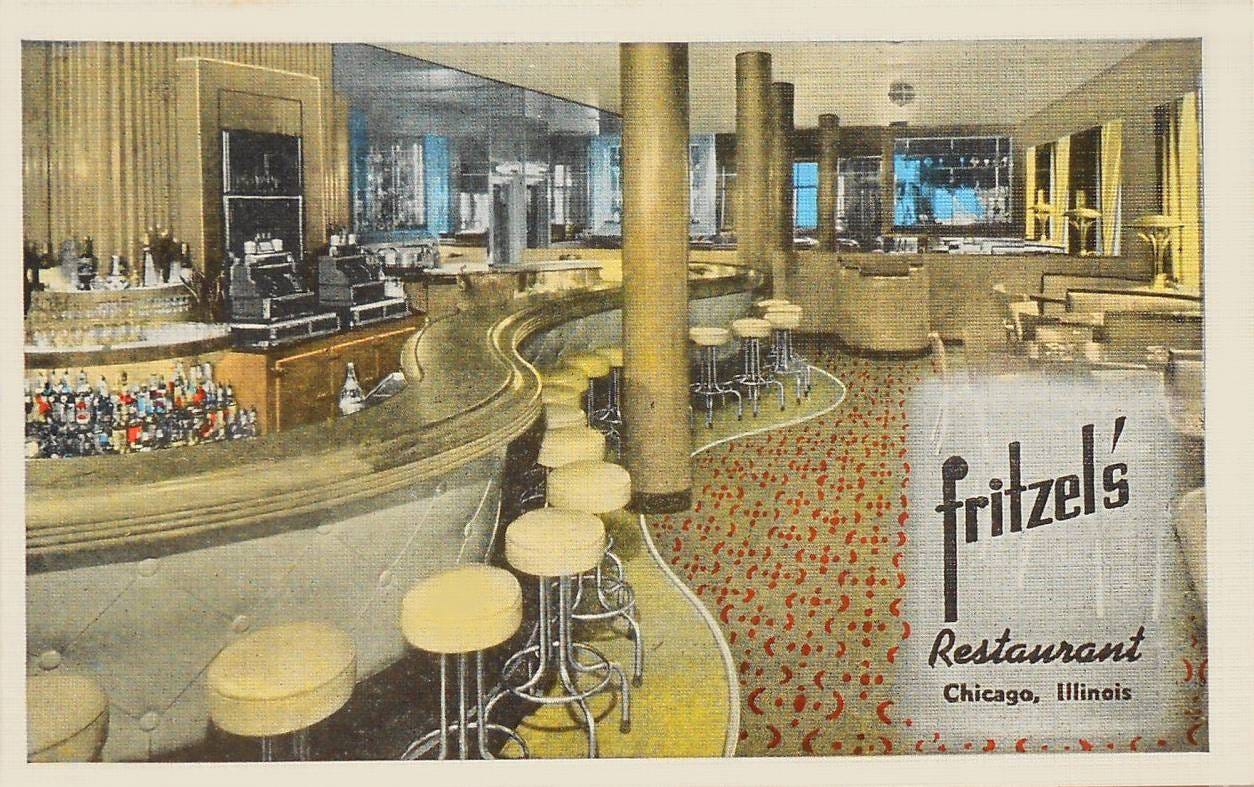

June 11, 1972: So long Fritzel’s

Chicago Sun-Times

by Hugh Hough

Fritzel’s, a Chicago restaurant institution at State and Lake, serves its last lunch crowd. Maitre d’ Jerry Rossini estimates they’ll serve up to 700 as he works the last lunch shift.

“This is how it used to be in the old days—the days when we didn’t have to hang up a going-out-of-business sign to draw crowds,” he says.

See last week, June 3-4, for a full Fritzel’s rundown with Robert Billings’ farewell in the Daily News.

Hugh Hough notes that Fritzel’s signature onion bread “was vanishing at an astonishing pace” along with the Kupcinet Special Salad, named for Sun-Times gossip columnist Irv Kupcinet, “a veteran Fritzel’s table-hopper.” That’s “finely chopped lettuce, chicken, tomato, bacon, eggs, beets, Swiss and American cheese” for $2.94—$19.91 in 2022 money.

There are some celebrities, as usual—radio personality Paul Harvey and Bear great Sid Luckman—but Hough concentrates on a table with four restauranteurs whose then-thriving establishments will also be unknown to most readers 50 years later:

“Gene Sage (Sage’s East), Stan Rapp (Red Carpet), Ray Castro (Jaques, et al) and Sam Batt (Batt’s).” (See Feb.10 for a look at the iconic Jewish deli restaurant Mama Batt’s, in that day’s “Charlie Cherokee Says” in the Defender.)

The restauranteurs “agree with the assessment of Fritzel’s general manager Wayne Boucher that Friztel’s died because of a sharp fall-off of nighttime diners in the Loop area.” Boucher stops by the table to chat with his colleagues and jokes:

“Hell of a publicity stunt, isn’t it? Look at that crowd.”

“‘Right, Wayne,’ Sage replied. ‘But what are you going to do for an encore?’”

June 11, 1972: Fitz to Fritzel’s: Drop Dead

Chicago Sun-Times

by Tom Fitzpatrick

Fitz brings us right back down to earth with a complete lack of any sentiment for Fritzel’s.

“To me, a great landmark is not a place where two people go for dinner and come out with a tab for $50,” he grouses. “A grand landmark is not a place where you drive up to the door in a Fleetwood Cadillac and give the doorman five bucks to park your car illegally without getting you a ticket.”

FWIW, that’s $337.50 for dinner in 2022 money, and $33.75 to the doorman. That is pricey, even after hearing that the Kupcinet Salad was $20 for lunch. But Fitz ignores the real issue here: A healthy downtown in a major city should be able to support a few ridiculous places like Fritzel’s. In 1972, Chicago’s Loop is becoming a ghost town at night. That’s why Fritzel’s is closing, and it doesn’t matter if you don’t care about the onion bread—this is not good for Chicago.

Fitz goes to Fritzel’s for its last dinner crowd and describes it like something out of “Madmen”—picture Pete in this scene, as seen in the last season of the show as the characters edge toward the ‘70s, plus local TV cameras covering the event:

“In the bar, middle-aged men with toupees and mod clothes have taken a night off from their families in the suburbs and are trying to make out with the ambitious young secretaries who have stayed downtown to hunt.”

In case you think he’s making that up, Fitz gives us specifics:

“But what about your wife?” One says as she sips her martini.

“My wife, dear girl,” her new friend says, “is in Lincolnwood. She’ll be watching the television later. We better not eat here.”

“Well, I’ll say this for Fritzel’s,” Fitz concludes. “It went down Friday night in its own style. The celebrities were there. They all fawned over each other. They were loud and they all uttered a lot of cheap sentiments about the passing of an era.

“It must have been a lot like that in the first-class dining room of the Titanic, too.”

June 11, 1972

Chicago Today

June 11, 1972

Chicago Today: Father Dubi profile

by Mary Leonard

Who remembers the lyrics to Paul Simon’s 1972 song “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard”?

Whoa, in a couple of days they come and take me away

But the press let the story leak

And when the radical priest

Come to get me released

We was all on the cover of Newsweek

Simon had to mean the Berrigan brothers, Fathers Daniel and Philip Berrigan, who took a star turn on the cover of Time in 1971. In 1972, Father Daniel recently got acquitted in yet another federal political conspiracy trial that came to nothing.

But radical priests, or at least politically and socially active priests, are in the air. In Chicago, we already had the more established Father George Clements at Holy Angels, and now young Father Dubi. Daily News top reporter Lois Wille profiled Father Dubi on May 2.

Now Mary Leonard surveys young handsome Father Dubi, “the 29-year-old associate pastor of St. Daniel the Prophet Catholic Church; the Southeast Side son of a steel worker; the effective, pull-no-punches spokesman for a growing number of Chicago’s ‘little men.’”

As co-chair of the now prominent Citizen’s Action Program (CAP), Dubi is in the forefront of the anti-Crosstown Expressway movement. U.S. Rep. Roman Pucinski threatened to punch him recently. Last week, Dubi “helped win a major citizens’ victory when both the City Council and County Board voted budget cuts and probable tax reductions”.

Father Dubi reveals that his family just had an “average” commitment to the church—he even attended public schools rather than Catholic as a kid. He was “scared to death of nuns”. But Father Dubi got an “invitation” to the priesthood from several different sources:

“I worked as an Andy Frain usher with a group of seminarians who invited me to join them,” he says, plus a teacher and his gramma both suggested the priesthood. Dubi started at Quigley Seminary and went on to Mundelein, where a new rector led him to “a new, deep involvement in social issues, discussions of poverty, war, peace and race”.

But Father Dubi had to learn to make his social agenda work with the needs of his parishioners, which took at least a year. “I put all middle-class people into the same bag. I thought they were all affluent—with two cars and a color TV—all racists and all super patriots…Well, it didn’t take me long to see that this model was not viable. These people do have social concerns and problems—but they are powerless to have their interests acknowledged and acted on by people in the public sector.”

Dubi started CAP as the Campaign Against Pollution in 1970, and the movement took off from there to include more issues like the Crosstown. But, he says, “First and foremost, I am a parish priest with liturgical and Christian education responsibilities.”

June 11, 1972

Chicago Today

by Bruce Vilanch

Regular readers may recall the first TCD1972 look at Bruce Vilanch’s regular column, TV Report, in which he both skewered “Hogan’s Heroes” as “probably the worst comedy show ever put on TV” and flattered former “Hogan” star Bob Crane, who was in town hosting the Chicago Auto Show and trying to make money to produce a play on Broadway.

As I wrote then:

Bruce Vilanch will leave Chicago Today and go to Hollywood. Wikipedia incorrectly says he worked for the Tribune. This makes sense from Wikipedia though: “As an entertainment writer, he began spending time with as many celebrities as would let him.” Wikipedia says Bruce Vilanch made friends with Bette Midler this way and wrote material for her 1974 Broadway show. And he was off!

You may know Vilanch for his time on Hollywood Squares, or for famously writing for the Oscars show for many years, among so many other enterprises including his 2000 off-Broadway show “Bruce Vilanch: Almost Famous.”

If Wikipedia’s bio is correct, this article would have been part of Bruce’s ticket out of Chicago and into Hollywood.

“My dear, you must hear that Bette Midler,” Bruce starts.

“First of all, she is very busy these days. Busy, busy, busy. That’s all that girl is. Running, running.

“From the studio, where she is supervising the mixing of her first singing album for Atlantic Records, to the rehearsal hall, where she is racing thru her material for Mister Kelly’s (where she opens tomorrow night) and Carnegie Hall (where she appears June 23) to the dressmaker, where she’s having new sequins stitched on her capri pants, to her Greenwich Village apartment…and leaping to the window to watch the German shepherds attack the people.

“Whew. I mean, this girl is busy.”

Bette’s road started in Paterson, NJ with a stop on Broadway as one of the three daughters in “Fiddler on the Roof,” then she “began showing up at all sorts of places around Manhattan, her hair done up like Gilda, her feet wedged into platform heels, her shoulders padded to the walls, her cupid’s bow lips parted in song as she would perform entire Thirties musicals before your eyes.”

“Then Johnny Carson started putting her on TV and she arrived at Kelly’s, singing ‘Shah-boom’ and bringing conventioneers up on stage to form her backup group, Bette and the Bang-Bangs.”

Bette backed off the camp after Milton Berle said she looked like him in drag, writes Bruce. Finally, she “found herself warming up the Saraha Inn audience in Las Vegas for Johnny Carson.”

“Right,” says Bette at the end of this breathless article. “Let’s just sit down and dish. Nobody dishes anymore. I love to dish.”

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

Don't forget that Western Electric also made portable radar units for the US Army during the Korean War. WE built that weird raised roadway around 6600 W. Grand, that confused people for years, as the ramp was removed the jeeps with the radars used to get to the top, as that was the highest point around Chicago. All that was left for decades was the short elevated road.