Note: If you’re a new reader, start with Chapter One: A Good Life Ruined—and see you back here soon. To access all site contents, click HERE.

Unnecessary But Motivating Chapter Quote:

Time dissipates to shining ether the solid angularity of facts. No anchor, no cable, no fences, avail to keep a fact a fact. Babylon, Troy, Tyre, Palestine, and even early Rome, are passing already into fiction.

-- Ralph Waldo Emerson, History, 1836

Part A - The Bench

I’ve known Steve my whole life. Naturally I thought because I knew him, I knew him. For years my brain automatically soaked up all his stupid quirks, like the way he’d reach up with his thumb and index finger to rub the uneven, stubby tip of his right ear where it got mangled as a kid.

Or the double-knotted bow he always tied on his shoes. Have you ever read about somebody in a tornado getting their shoes blown off their feet? That would never happen to Steve.

Don’t even get me started on the way he’d talk about “Vince” and “Mike” like they were personal friends.

I knew all those things about Steve, but I never wondered about any of it. I never even found out what the hell happened to his ear.

And then one day I found out the guy I thought was Steve didn’t exist. My Steve was a fictional character I completely made up, as if I was a writer, which I sure wasn’t. Christ. I cranked out the most obvious, stereotypical hero possible in my head, with zero personality and no goals beyond watching the White Sox and the Bears.

If the Steve I made up had a tragic flaw, it was that he was created by me.

Have you ever done that? My guess is people who think they haven’t done that with somebody—friends, relatives, grammar school teachers—possess even less self-awareness and personal insight than I did. My guess is those people go into politics.

The day I found out my Steve was made up, at that precise moment, I was walking away from real Steve. I’d just done something entirely new for me at that time: I asked another human being a probing, personal question. Of all people, I asked Steve. I don’t know what got into me. One minute we’re sitting on a bench, and the next, I’m trying to explore the mysteries of life with Steve.

Looking back, sometimes I think it was the sitting on that bench, all by itself, that did it. What is it about benches? I don’t know.

It was a quiet fall afternoon. The bench is on a triangular island of grass and trees surrounded by the looping drive of East View Park, a one-block street in Hyde Park where Steve lives now. Three grassy berms form a smaller triangle within the island, with a bench set against each berm. My bench is set against the northern berm, on the skinny tip of the island facing the East View Park entrance on 54th Street.

A smattering of people were walking down the block, and a couple of kids were playing soccer on the island—everybody calls it “the island” as if the street is a body of water. There was a Jensen’s moving truck parked a little ways behind the bench.

I particularly remember that Jensen’s truck because Steve was so happy to see it. He said Jensen’s movers were from Roseland, and the trucks used to be all over the place. In fact, he said Dick Butkus used to work for Jensen’s. “I can’t remember the last time I saw one,” he marveled.

That’s about when I asked Steve that question. Not being used to any kind of true intimacy, I didn’t look at him while he answered me. I watched a crow hopping around on the grass instead. I knew without looking that Steve was probably rubbing his ear, or checking to see if he had his scapular on.

I listened, but I didn’t let myself take his answer too seriously.

“That’s cool,” I said when he finished.

“Juicy Fruit?” he asked, holding up an open pack of gum.

I’m not big on gum. It tastes great for three seconds and then your mouth feels like dried cement.

“No thanks,” I said. “I’ll see ya later.” I got up and started off, walking south across the island toward its wider base, where the drive loops around the southern end. East View Park doesn’t extend all the way to 55th Street, mind you. If there were a cross-street at the southern end, it would be 54th Place.

I got about halfway across the island when I glanced back in a kind of involuntary muscle movement, like blinking. I’ll never forget the look on Steve’s face as he watched me walking away. Talk about painful. Talk about embarrassing. It was like stumbling in on your dad going to the bathroom. Everything Steve was thinking and feeling was right there, and he had no idea the whole world could read his soul in the creases around his eyes and the slant of his mouth.

I couldn’t stand it, so I pretended I was looking at that crow again. It was squawking in the tree right above Steve. Then I turned right back around and kept going. Same as you’d slam the bathroom door and act like you’d never seen your dad on the toilet. The whole thing took about a second. I’ve spent more time scratching a mosquito bite.

I’d only gone a few more steps when I heard an earsplitting noise behind me. Screeching. The kind that always involves heavy metal. My head jerked back toward Steve. It was so loud, I thought the Jensen’s moving truck must’ve jumped the curb and plowed over the bench. In the split second my head spent swiveling around, I saw the whole scenario:

The Jensen’s truck driver was texting his wife to remind her to record the season premiere of 24 that night. It was his favorite show. They’d been playing endless radio ads for it all week. Everybody knew CTU agent Jack Bauer was going to say, “I need a hacksaw.” The truck driver couldn’t wait to see what Jack would do with this staple of basement workshops everywhere. The truck driver only used his own hacksaw once a year to trim a Christmas tree trunk to fit in a red metal tree stand. He knew Jack Bauer wasn’t going to use his hacksaw on a Douglas fir.

I’d finish turning around to see the truck driver draped across his huge steering wheel. He’d never find out what Jack did with the hacksaw. I’d see Steve’s white leather gym shoes sticking out from under the truck’s right front wheel. The double-knotted bows would still be tight, still in place. I’d stare at those shoes as if they were going to curl up and disappear, like the Wicked Witch of the West.

As my head completed its spin, I was thinking: What if Steve didn’t have his scapular on after all? We’ll get into all Steve’s Catholic stuff later, but let’s stipulate now that if you wear a scapular, it’s crucial to have it on if you get run over by a truck.

But of course it was all in my head. You already understood that Steve was fine, right? I wouldn’t have thrown in the picture of Jack Bauer if he was really underneath a truck. The shocking noise wasn’t even the Jensen’s moving truck. Life is seldom so conveniently dramatic. I don’t know about you, but my big moments are pretty pedestrian when they’re actually going on. Often they’re not even moments. They’re flabby, formless things that unspool for a day or a week, until you forget about them or get bored and turn on the TV. Maybe if my life had a soundtrack, I’d know when to pay attention.

What really happened, not far behind Steve, was a typical boring real-life thing— two cars in a fender bender. One driver pulled out of a parking space without looking. Nothing serious, just loud. Grating. The kind of frequency you feel in your teeth whether you have fillings or not.

Everybody in sight whipped their heads around toward the squealing sound in one mass, simultaneous reflex reaction—including me, with my ridiculous fantasy about the Jensen’s moving truck.

But not Steve. He was still sitting where I left him, his back to the accident, still watching me with that look on his face I’d never seen before on anyone.

That’s when it hit me: Steve actually believed his answer to my question. He wasn’t just talking, like most of us, to fill an awkward silence or score points as if life were an endless high school debate tournament. And he believed my answer, too, when I said, “That’s cool.” He didn’t think I’d just said it for something to say, although I had. The look on Steve’s face as he watched me walk away meant I didn’t know Steve at all. His life story wasn’t the boring plot I’d followed for years. I’d been watching a minor subplot.

I felt bad about not taking the piece of Juicy Fruit, as if that would’ve made any difference. But you know how people like to give you something.

In that moment, I knew I had to find out everything I could about Steve. His real story. Maybe it was because I thought he was crushed under the Jensen’s moving truck for that split second as my head turned. It’s kind of pathetic how people have to be killed, or maybe killed, before you take them seriously.

I’ll tell you later what I asked Steve, and what he told me. But I can’t tell you now because it won’t mean anything if you don’t know Steve. I’m not even going to tell you who I am to Steve, because that won’t mean anything either.

Maybe you’re thinking, “I know Steve, I just read about him walking to work with two black eyes in 2003.” OK, I gave you a little introduction to grown-up Steve in Chapter Two. But you don't actually know somebody from seeing them at work for a single day. I didn’t know Steve after spending a lifetime with him.

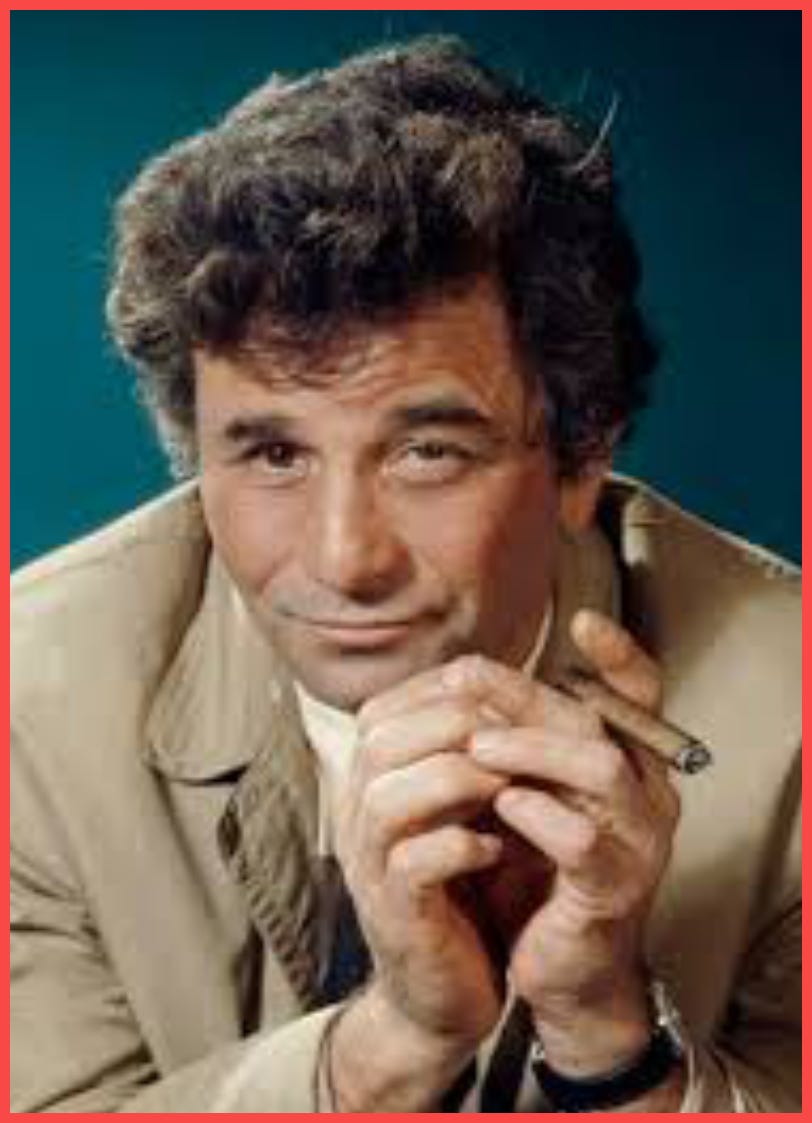

Here’s a picture of Steve at about eight years old, so circa 1970. Now you’ve seen him as a kid, and you’ve seen him as an adult—but you still only know as much about him as I did when I started out.

All in, I spent at least ten years on my Steve project. I didn’t plan that, and I didn’t figure it would turn into a book. But the more I heard and read, the more I needed to write it all down to get it straight in my own head. Steve is like a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle. Some people fit a few big pieces together and say, “Well, you get the idea. It’s a lighthouse, there’s the picture on the box. That’s enough. Let’s see what’s on TV.” I can’t do that. Yeah, it’s a lighthouse, but what else? I want to put all the pieces down on a table and move them around, see how they fit together. Why, specifically, does this piece mesh with that piece?

And when you see the whole lighthouse, you can figure out exactly which one it is. Each lighthouse is painted differently, so old-time sailors miles offshore knew where they were by the color or the pattern of the stripes. For night identification, the lighthouses flashed unique signals.

I want to know if my puzzle shows the lighthouse near the mouth of the Chicago River, or the Big Sable Point lighthouse in Ludington, Michigan. What special code would the lighthouse flash, if I were a sailor 100 years ago? To me, those details matter. And the doing of the puzzle, itself—that’s not a waste of time. Isn’t it better than watching another rerun of Gilligan’s Island?

How did I go about learning Steve’s story? I didn’t tell him what I was doing, that’s for sure. I didn’t tell anyone. I interviewed his friends and family, stealthily, never revealing my true purpose. Sometimes I had a tape recorder hidden in my pocket. Sometimes I ran home and jotted down notes. People thought they were just having a drink with me, or I’d dropped by to return a hammer or whatever. They’d say, “You ask an awful lot of questions” or “Why you givin’ me the third degree?”

And I’d shrug and say something like, “Oh, you know me. So anyway, do you remember that old building at State and Randolph, the one on the northwest corner, with some whacky store called Shoppers Corner on the first floor? Steve said it was kitty corner from Marshall Field’s, and it had a big red electric Magikist lips sign taking up most of the Randolph side. He said he thought the neon lines in the letters of the Shoppers Corner sign were pink. And there was a King Castle next door.”

I studied Steve. I read books, revisited the important places in his life, watched the formative media of his 1960’s and 70s youth. For movies, Ben-Hur, The Ten Commandments and Planet of the Apes to start. Thought I’d get all the Charlton Heston out of the way first.

Then, stuff like Cool Hand Luke and The Great Escape later on. For TV, Columbo and The Dick Van Dyke Show--not to mention enough Twilight Zone to permanently weird me out.

I spent entire weekends in the microfilm room at the University of Chicago Regenstein library, cranking my way through thick spools of the Chicago Daily News, the Sun-Times, Chicago Today, and the Chicago Defender. The Tribune was already available digitally. I started just looking up a few things, but I couldn’t read just one article and ignore everything else on that page or in that issue. The stories all fit together in a bigger puzzle—there’s that analogy again—and I couldn’t look at a picture on a box cover to see what it was. That’s where I met Gil, and where I realized newspapers were so important.

News, wrote Mark Twain, “is history in its first and best form, its vivid and fascinating form, and…history is the pale and tranquil reflection of it.”

If you’ve ever read even the most entertaining historical book and then examined an actual newspaper from the day of the exact same events, you know this is true. A newspaper, versus a narrative composed at leisure years later, has a completely different energy. It’s a local bar band jamming in front of a rowdy late night audience, versus a hyper-produced hit, created with computers in a studio cocoon, every note in place. And don’t get me wrong, I love some good history. It’s just not the same.

When a book quotes a newspaper or a diary—the personal equivalent of a newspaper—it’s not quite like holding that newspaper or diary in your own hands. A true historian doesn’t research primary sources just for information. They want that elemental level of feeling there.

But maybe you grew up after newspapers. Maybe you’ve never even seen a current one, much less come across a carefully preserved copy of, say, a newspaper from the day of the JFK assassination. People used to save newspapers from those kind of earth-shattering events, wrapping them carefully in plastic and laying them gently on a closet shelf, like pressed flowers. Why do you think they did that? I think it’s because the newspaper made the event so real that saving the paper became a form of respect for the event and the people involved, almost like a burial.

For all a newspaper story’s possible imperfections, when you read it, you know you’re seeing the same account thousands or even millions of people read on a single day in the past. This is what a reporter and some editors thought they knew in real time. Even if they got something wrong—of course they did and still do— this is what a vast newspaper audience learned about their world. This is what shaped the world for readers—including Steve, his family and neighbors.

Newspapers were a central, ubiquitous social force that we’ve already kind of forgotten, like a distant relative in a nursing home on the other side of the country. “Oh, are they still around?” you might think every once in a while. If we really want to get into Steve’s 1972 world, we all have to understand this. So let’s remind ourselves of the central place newspapers played in everyone’s lives once upon a time. And let’s do it with another big part of Steve’s 1972 world—Columbo.

NEXT UP: Columbo: Murder That’s Black and White and Read All Over

Columbo helps us understand the ubiquity of newspapers in 1972, as the Bertolucci’s watch the seminal first season episode “Lady in Waiting” on December 15, 1971 from their front room in Roseland at 12426 S. Wabash.

SUBSCRIBE - FREE

If you’re not immediately repelled, why not subscribe? It’s free, after all. You’ll receive a new chapter monthly via email, and find out why I am spending so much time on the story of this one guy. You’ll also get a weekly compilation of the daily items on social media: THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, and MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY.

And why not SHARE?

Maybe you know someone else who would enjoy reading about a ten-year-old Italian-American kid on the South Side of Chicago in 1972. Didn’t your parents teach you to share?

The photo of State & Randolph was taken no earlier than 1974. You can read Pam Grier’s name together with The Arena on the Oriental marquee to the far left. According to IMDB, it was released in 1974.

Did you know that the Obamas lived in East View Park?