Chapter 3 Notes, Part A: Jack Bauer, MAD Magazine, the Enema Bandit & more

Say, too bad Jack Bauer didn't go after the Enema Bandit.

HOW DO NOTES WORK? Each book chapter comes with Notes on key topics that pop up as our story progresses—mostly fun, but like most life, sh*t can get real when you least expect it. I don’t know why it felt right to put that asterisk in ‘sh*t,’ but it did.

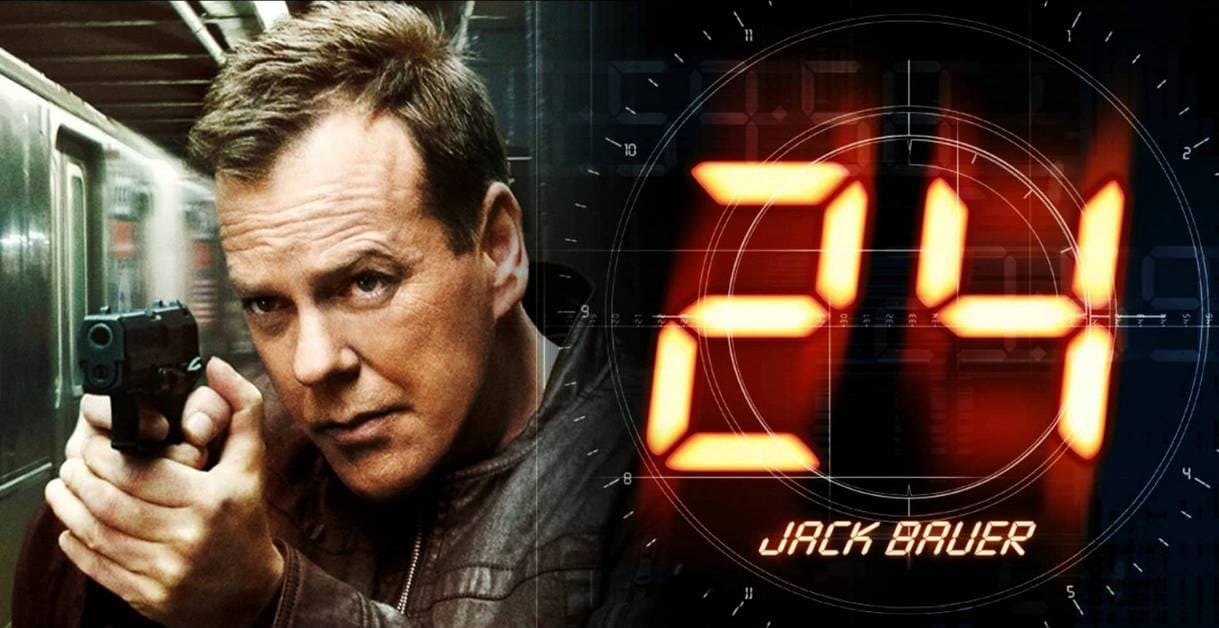

24

Early 21st century television series centering on Jack Bauer, agent for a fictional U.S. government agency called “Counter Terrorism Unit”—“CTU” for short. Each episode “occurs in real time,” as Jack’s voiceover notes at the start of every show.

Each singular threat to humanity begins and ends in exactly one day, or 24 one-hour episodes (a “season” as it was called) of 24. Jack Bauer is not a superhero, but he must constantly exercise superhuman self-control in order to say “Dammit!” rather than really swearing whenever he’s thwarted from saving the country or world, because 24 aired on network television.

Jack Bauer is the coolest, blankest secret agent, like if The Matrix’s Agent Smith was a good guy—but Jack is more unintentionally funny.

Many viewers probably felt guilty cheering for Jack Bauer since he is also a frightening personification of the post-9/11 mentality that torture was OK for suspected terrorists, despite clear evidence that it doesn’t work.

That said, go watch the first episode of Season Two and find out what Jack does with the hacksaw.

Gilligan’s Island

Gilligan’s Island is based on the premise that an eclectic group of five tourists boarded a small sightseeing boat called “The Minnow” for a three-hour cruise around Hawaii, and an unexpected storm shipwrecked everyone on an uncharted desert island.

More importantly, it’s the kind of typically awful 1960s sitcom that played nonstop in reruns weekdays when Steve was a kid. If you were home sick from school, you’d see an episode of Gilligan’s Island as surely as you’d see an I Love Lucy. Other reruns came and went on the daytime schedule—Hogan’s Heroes, Bewitched, Gomer Pyle—but Gilligan’s Island was nonnegotiable.

So Gilligan’s Island is the Uber-bad 60s sitcom. No one who watched TV in the 1960s or 1970s can escape its influence. The main characters have become societal totems equivalent to iconic folklore categories—the evil stepmother, the good huntsman, the wicked old crone.

The main characters:

Ship’s captain Skipper, bombastic but goodhearted (Alan Hale)

First mate Gilligan, stupid but goodhearted (Bob Denver)

Millionaire Thurston Howell III, bombastic but goodhearted (Jim Backus)

Mrs. Howell aka “Lovey,” ditzy but goodhearted (Natalie Schafer)

Movie star Ginger Grant, bombshell but goodhearted (Tina Louise)

Girl-next-door Mary Ann, good girl and goodhearted (Dawn Wells)

The Professor, smart and goodhearted (Russell Johnson)

The Professor could make a radio out of bamboo, but somehow could not advise his goodhearted group of fellow castaways on how to build a raft out of bamboo and get the hell out.

That said, I’ll be adding a post that is the equivalent of the Great Books course, but for 1972—GREAT AND GRATING BOOKS & MEDIA 1972. Unlike the Great Books, a goodly share of GREAT AND GRATING will be books, TV or movies I would never recommend to anyone in the usual sense of the word. The goal will be to provide a syllabus for studying the time period, and Gilligan’s Island will be on it as surely as you had to read either The Scarlet Letter or The Deerstalker in high school American Literature.

By the way, did you know the Great Books program began at the University of Chicago?

MAD Magazine

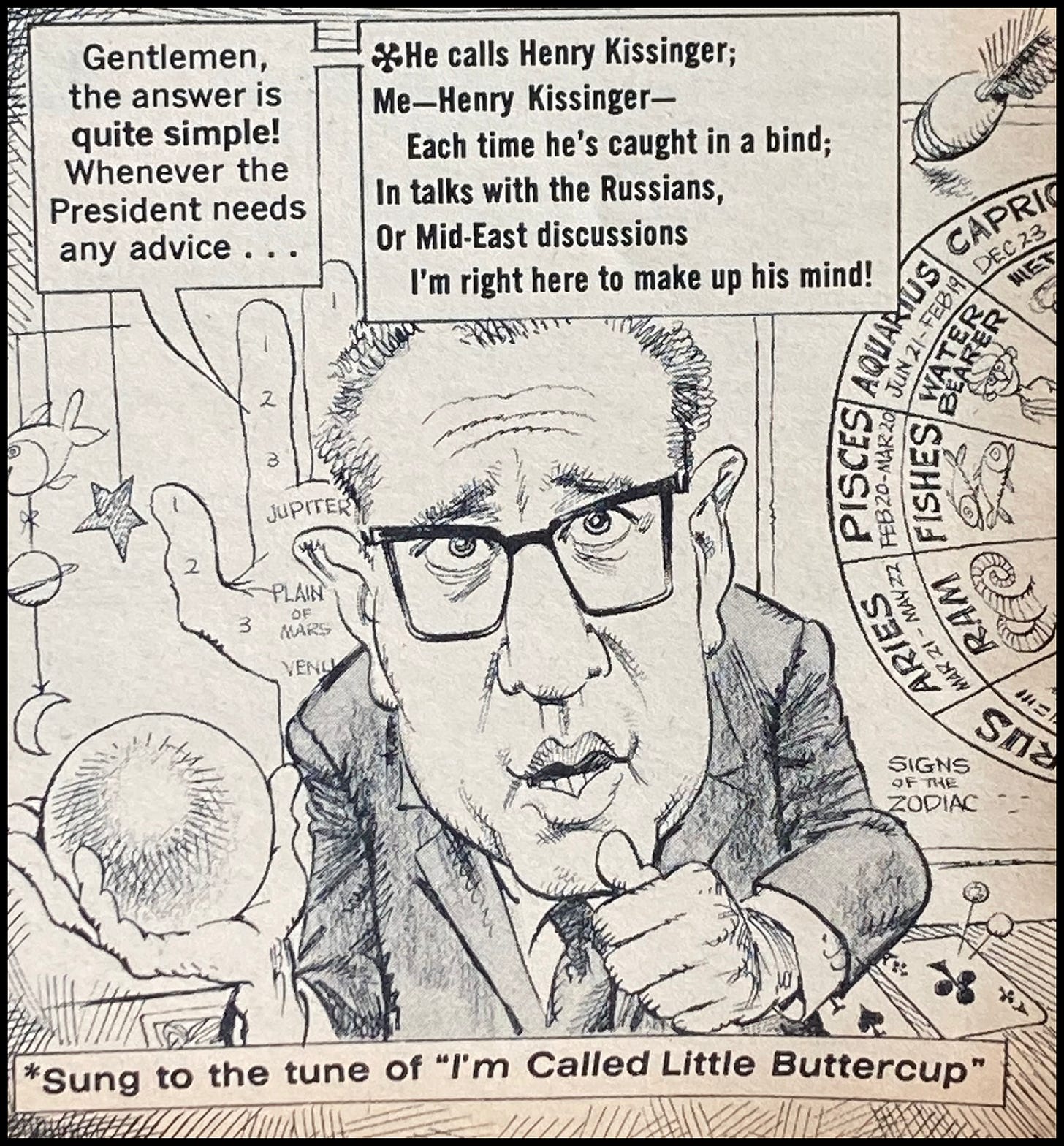

MAD Magazine was read by kids and teenagers, but written by adults for--I have to think--themselves. They weren’t writing for other adults, because adults didn’t read MAD. And you’re not really writing for kids with pieces like a look inside Ralph Nader’s wallet (March 1972), or a Gilbert & Sullivan parody set in the Nixon White House, featuring “He calls me Henry Kissinger” sung to the tune of “I’m Called Little Buttercup” (April 1972).

The important thing about MAD is that the writers and cartoonists, in aiming at themselves, aimed over (or under) the heads of the average 1950s adult and straight for the sensibilities of their Baby Boomer kids. MAD began in 1952, and the 1950s were in dire need of MAD.

Those first readers passed MAD down to their younger siblings, leaving MAD behind as they grew up to create National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live. Then poof—MAD was everywhere, though you couldn’t see it. MAD wasn’t a handful of comedic seeds spread across the cultural landscape by Alfred E. Neuman drawn as Johnny Appleseed, sprouting in every possible medium. MAD was the nitrogen in the nation’s psychic soil, from which everything grew.

“The message MAD had in general is ‘The media is lying to you, and we are part of the media,’” Pulitzer prize-winning author and cartoonist Art Spiegelman told NPR in 2004. “It was basically…’Think for yourselves, kids.’”

In the ‘50s, “Think for yourselves” was a subversive message.

In 1972, a good example of MAD’s meta subversive message was “Truly ‘Relevant’ TV Shows” from the March issue. “In case you haven’t noticed, this has been the year on Television for what the Networks like to call ‘Relevant’ programs,” read the introduction. That was another thing Steve and his friends loved about MAD—it never talked down to you. “But have you ever noticed that these so-called ‘Relevant’ shows never quite get around to taking the worst exploiters of all to task? For some mysterious reason, broadcasters haven’t yet discovered a single thing wrong with the Television Industry itself, or the Sponsors that support it!”

MAD envisions those Truly Relevant TV Shows for us, such as a WJM newsroom where Mr. Grant won’t cover the plane that just crashed outside his office window because airlines are big advertisers, and tells Murray to cut the story about the biggest company in town losing a government contract: “Forget it! I own stock in that firm, and I could lose a bundle if word leaks out before I sell!”

Think “Catch-22” in low-brow cartoon form, substituting Alfred E. Neuman for Yossarian—except MAD and Neuman came before “Catch-22.”

MAD began as a comic book published by William Gaines’ EC Comics. Gaines gave contributing writer Harvey Kurtzman free reign to create a humor title to complement best sellers like Tales From The Crypt. No surprise then that Issue #1 was a horror story parody, “Tales Calculated to Drive You MAD.”

MAD morphed to a magazine format in 1955, by some accounts forced by the repressive, censorious 1950s culture it mocked. A 2019 MAD appreciation by Jordan Orlando in the New Yorker—one of many that year as MAD ceased regular publication and newsstand sales—implies that Gaines turned MAD into a magazine specifically to avoid the new Comics Code Authority and its heavy censorship:

“In the spring of 1954, the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held hearings in New York City on the menace of comics, largely prompted by the notoriety of the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s best-selling book “Seduction of the Innocent,” which contended that “chronic stimulation, temptation and seduction by comic books . . . are contributing factors to many children’s maladjustment.” Gaines was called to testify, and disputed the arguments in Wertham’s book, insisting that “delinquency is the product of the real environment in which the child lives and not of the fiction he reads. . . . The problems are economic and social, and they are complex.” His testimony was not persuasive, and the hearings resulted in EC and other comic publishers acquiescing to self-censorship, necessitating the creation of a Comics Code Authority, which would henceforth review every issue of every title before granting permission to display a “Seal of Approval,” without which the comics could not be sold.

No EC titles survived the purge except Mad, which escaped the Comics Code by expanding its trim size to become a “magazine”—and this new, adaptable hybrid format was the key to its longevity.”

Switching formats on purpose to avoid the Comics Code would make sense, but I’m not sure that’s accurate. If enlarging the trim size was all it took to evade the Comics Code, why not do so for all EC’s comic books? In addition, William Gaines said otherwise in a 1992 interview, the year of his death at age 70, talking with Steve Riggenberg in Gauntlet. I couldn’t access the issue, so I’ll have to quote Wikipedia quoting the article:

Mad "was not changed [into a magazine] to avoid the Code" but "as a result of this [change of format] it did avoid the Code." Gaines claimed that Kurtzman had at the time received "a very lucrative offer from...Pageant magazine," and seeing as he, Kurtzman, "had, prior to that time, evinced an interest in changing Mad into a magazine," Gaines, "not know[ing] anything about publishing magazines," countered that offer by allowing Kurtzman to make the change. Gaines further stated that "if Harvey [Kurtzman] had not gotten that offer from Pageant, Mad probably would not have changed format."

I can’t think of any reason Gaines would deny thumbing his nose at the Comics Code Authority, when nose-thumbing was MAD’s entire raison d’etre. And the comically-named Authority wasn’t likely to cause anyone trouble in 1992, when kids were well on their way to committing mass murder in video games. Either way, MAD switched to the magazine format and quickly became required reading for those of a certain underage.

Founding editor Harvey Kurtzman left a year later in 1956 and Al Feldstein took over, staying until 1985. Many insist MAD never recovered from Kurtzman’s departure. Really? Well, you say schmuck, millions of kids from that time period said nudnik and subscribed to MAD.

Under Feldstein, MAD reached peak circulation in 1973 at just over two million, and those millions weren’t thinking, “Gee, this MAD cover parodying The Sting movie poster with Nixon and Agnew posing like Robert Redford and Paul Newman’s conmen characters--holding up subpoenas and tax forms instead of cards and money--isn’t as culturally astute as the May 1954 cover made to look like Life magazine with a hideous cartoon woman headlined ‘Beautiful Girl of the Month Reads MAD’”.

Since MAD’s audience was almost exclusively kids and teenagers, the typical MAD reader didn’t understand half the literary, historical or even pop culture references in the magazine when they started devouring it. Many a gentile MAD reader grew up thinking common Yiddish terms were funny words invented by MAD. After all, their parents couldn’t tell them what “meshuga” meant, and it wasn’t in their 1972 dictionary.

When the issue’s regular parody was a movie, MAD readers were mostly too young to see those films at the theater. For them, MAD’s Rosemia’s Boo-Boo was the original, and Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby the doppelganger. Consider our banner year, 1972, when the movie parodies included the R-rated Carnal Knowledge, The French Connection, Dirty Harry, and The Godfather. Steve didn’t see any of those movies except The Godfather. His Nonna took him, thinking it would be educational for him to learn about his heritage.

MAD readers were reading above their pay grade, as low-grade as MAD reliably remained. In so doing, readers learned as much about the world from MAD as they did from newspapers.

MAD was always self-deprecating, labeling itself “trash” and “garbage” produced by the “Usual Gang of Idiots.” Some cultural critics describe this now as a sign of defiance. Maybe? I bet they just thought it was funny. To Steve and his friends, it was endearing--a sign that MAD was one of the them, as if it was produced not by grown-ups in Manhattan but a kid down the block who knew how weird the adult world looked when you were looking up at it.

The avatar of MAD, or mascot as he’s often called, is Alfred E. Neuman--a gap-toothed kid with the permanent smirk that all kids know will drive grown-ups insane. Many wonder where Alfred E. Neuman came from, as if MAD writers arduously searched for a spiritual guide, a Virgil to the comic world. Nope. Alfred E. Neuman is merely a cartoonish drawing that had been floating around publishing for many years, like a free piece of clip art you’d grab off the internet today. MAD chose Alfred as the personification of its attitude, and proceeded to put his face on every possible important person and character, and into every irreverent situation. In the midst of the hot 1972 presidential campaign, naturally that meant seeking the nomination at a national political convention. I don’t see any Democrats grinning over Neuman’s shoulder, so I guess he’s at the Republican convention below.

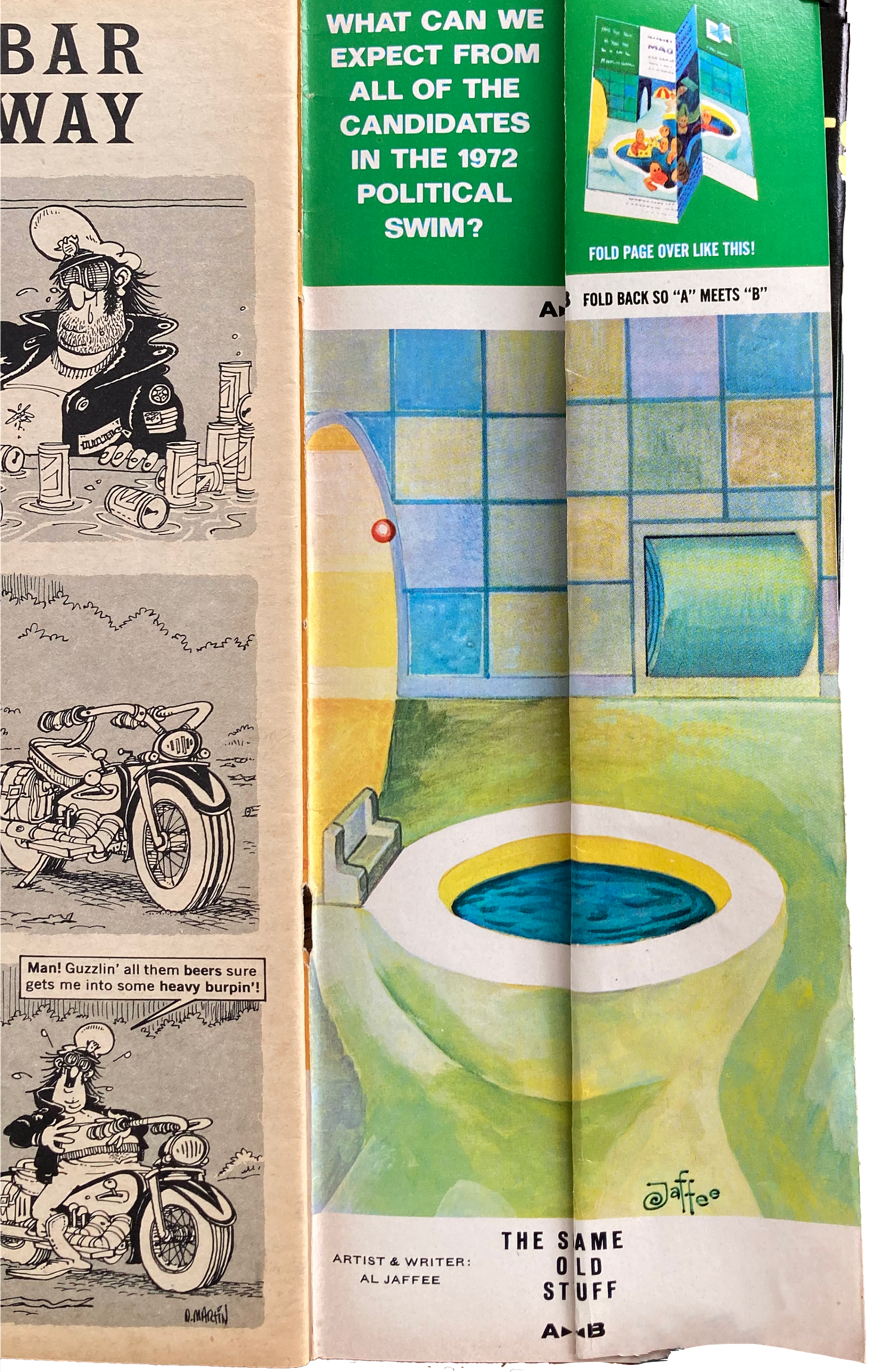

MAD managed to be political, but fair—making fun of extremes at both ends of the political spectrum, or all sides at once. Consider the MAD Fold-Ins for January ‘72 and October ‘72. The MAD Fold-Ins, by Al Jaffee, were typically the first thing a MAD reader flipped to, on the inside back cover. Each fold-in featured a sort of riddle at the top; a nearly full-page illustration in the middle; and at the bottom, a message repeating the riddle in a shortened message. When you folded the cover, matching up the A and B tabs at the very bottom of the page, you got the answer both by transforming the picture into something completely different, and altering the message at the bottom like a secret code. But first, without folding, you studied the drawing, looking for clues in the illustration at full size and struggling to imagine how the picture would change when you folded it.

You can’t fold these onscreen, so first we’ll show the full page, then the folded picture. Don’t cheat—scroll your screen to hide the answers until you’ve at least tried to figure them out. They’re not so easy—because they’re not really made for kids.

But was MAD really the most intellectually honest reading material available to Steve and his cohorts, as I claimed in Chapter 3? That was actually Gil’s observation, but he convinced me. Now I’ll try to convince you.

Let’s compare MAD to the Bible. As noted in Chapter 3, both were among the few reading materials besides newspapers reliably available in a typical Chicago working class home in Steve’s neighborhood.

If MAD seems an unlikely pairing with the Bible, consider this declaration from Pulitzer Prize-winning Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert: “I did not read the magazine, I plundered it for clues to the universe.”

You be the judge. I’m pretty sure Roger would give MAD the thumbs up.

MAD

“the usual gang of idiots,” according to the MAD masthead, usually eight times per year starting in 1952

BIBLE

an omniscient, omnipotent eternal being called “God,” via divine inspiration of often unknown people over hundreds of years, mostly B.C.E.

MAD

From the MAD movie parody of The Exorcist, October 1974 (bold-face from original text)

The Exorcist: “These are the standard tools for an Exorcism: the vial of Holy Water to douse the evil spirit, the Crucifix to hold the Demon at bay, and the Hostess Cupcake…

Assisting Priest: The Hostess CUPCAKE?!?

The Exorcist: You know it, Father! Exorcisms take time! Believe me, long about Midnight, you can get mighty hungry!

BIBLE

From The Healing of the Gerasene Demoniao, Luke: 26-39

“Then they sailed to the territory of the Gerasenes, which is opposite Galilee. When he came ashore a man from the town who was possessed by demons met him. For a long time he had not worn clothes; he did not live in a house, but lived among the tombs. When he saw Jesus, he cried out and fell down before him; in a loud voice he shouted, ‘What have you to do with me, Jesus, son of the Most High God? I beg you, do not torment me!’ For he had ordered the unclean spirit to come out of the man. (It had taken hold of him many times, and he used to be bound with chains and shackles as a restraint, but he would break his bonds and be driven by the demon into deserted places.) Then Jesus asked him, ‘What is your name?’ He replied, ‘Legion,’ because many demons had entered him. And they pleaded with him not to order them to depart to the abyss. A herd of many swine was feeding there on the hillside, and they pleaded with him to allow them to enter those swine; and he let them. The demons came out of the man and entered the swine, and the herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and was drowned.”

MAD

Don Martin cartoons; Dave Berg’s The Lighter Side; Spy v. Spy; Al Jaffee's MAD fold-in inner back cover; movie, TV and ad parodies

BIBLE

Hebrews sin, God kills them. Hebrews would like to take over other people’s cities, God tells Hebrews to kill everybody, including their animals. People sin, Bible writers assure readers God will send them to Hell to be tortured for all eternity in a lake of fire.

MAD

More Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions, by Al Jaffee, April 1972

BIBLE

Matthew 19:16-24

And, behold, one came and said unto him, Good Master, what good thing shall I do, that I may have eternal life?

And he said unto him, Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is, God: but if thou wilt enter into life, keep the commandments.

He saith unto him, Which? Jesus said, Thou shalt do no murder, Thou shalt not commit adultery, Thou shalt not steal, Thou shalt not bear false witness,

Honour thy father and thy mother: and, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

The young man saith unto him, All these things have I kept from my youth up: what lack I yet?

Jesus said unto him, If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come and follow me.

But when the young man heard that saying, he went away sorrowful: for he had great possessions.

Then said Jesus unto his disciples, Verily I say unto you, That a rich man shall hardly enter into the kingdom of heaven.

And again I say unto you, It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.

Jays Potato Chips

Long ago, right here on Earth, you could travel around America and find completely different local brands of potato chips in every little town and every big city. And they all had their own taste, unduplicated anywhere else. Something about the cut of the chip, the cooking method, and the type of oil or lard used to fry them.

Jays was Chicago’s brand, known for a relatively light chip fried in corn oil. Jays was “A Pip of a Chip,” and by 1953 everyone knew you “Can’t Stop Eatin’ Em.” In addition, Jays potato chip pencils very nearly supplanted all other pencils in Chicago, because they came free rolled up inside your newspaper, delivered on your front porch or into the evergreen bushes next to your front porch.

It all started, legend goes, when young Leonard Japp jumped off a freight train at 15th and Halsted in 1921, utterly penniless. He stopped in a nearby bar and the kind owner gave him a sandwich, let him sleep there, and helped get Japp’s first city job. Later, Leonard Japp worked nearly every job you can think of. He served as a lifeguard at Oak Street Beach and befriended Johnny Weismuller, future Olympic gold winner and iconic early film Tarzan. He sold cemetery plots, and for extra money he boxed now and then at city amusement parks like Riverview and White City. He was always trying to convince his fellow boxing chum Bob Hope to forget vaudeville and get into the promising cemetery business.

Jays got started on the South Side during Prohibition when Leonard Japp and a partner put down $5 on an old truck, bought some snacks, and started servicing Al Capone’s speakeasies. Capone discovered potato chips on a vacation to the snack’s birthplace: Sarasota Springs, New York. On his return, Capone demanded chips in the speakeasies. By 1929, Japp and his partner were making their own chips and operating 15 trucks.

The Depression took down Leonard Japp’s first business, along with Nona and so many others. But Leonard Japp put down a lucky bet on a horse one day and won enough to buy another truck. By 1940, Japp and a new partner had set up a potato chip factory at 4052 S. Princeton, five blocks due south of Comiskey Park, churning out Mrs. Japp’s Potato Chips. Do you think Leonard Japp popped over to Comiskey for a game every now and then? I do.

Mrs. Eugenia Japp became a vice president, widely known for putting recipes on Jays packaging. Mrs. Japp’s most famous delicacy was tuna casserole with potato chips crumbled on top—Jays potato chips, of course.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese war planes launched a sneak attack on the U.S. naval station in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The word “Jap” had heretofore been common shorthand for “Japanese.” The Japanese may not have cared for the term, but the average American thought nothing of it. For instance, in 1923 when a Japanese youth tried to assassinate future Japanese emperor Hirohito, the Tribune headline read “Assassin Tells of Attempt to Kill Jap Prince”. After Pearl Harbor, “Jap” became an ugly slur for the country’s arch enemy.

On December 8, grocers called up demanding to get Mrs. Japp’s Potato Chips off their shelves.

“I think people thought there was a little Japanese lady who cooked the potato chips,” Leonard Japp’s grandson Steven later told Chicago’s Channel 11. Mrs. Japp’s changed its name in either two days or two weeks, depending on which account you go with.

Jays was the number one potato chip in Chicago by 1950, according to Leonard Japp later in life, and this was probably so since the company could afford to sponsor a weekly Sunday night program that year on WGN—Jays Jamboree.

Jays designed and built a bigger factory at 99th and Cottage in 1955, on the edge of Roseland, and began filling the skies with the aroma of freshly fried potatoes.

All was well with Jays for many years. Jays fought valiantly against the spread of Lay’s and Ruffles potato chips, offspring of the national behemoth Frito-Lay’s. And Jays battled the 1970s introduction of that unholy dehydrated potato concoction, Pringle’s. By 1985, Jays employed 850 workers, with 400 working three shifts a day at the Jays factory. That year, Jays sold $64 million worth of potato chips.

But the Japp family sold Jays to national corporate giant Borden in 1986. Borden’s mismanaged the company and stopped advertising. In less than ten years, Frito-Lay brands were beating Jays in the Chicago market. The Japps bought the company back in 1994, with three generations of Japps working now—elderly Japp Sr. as chairman emeritis; Leonard Japp Jr. chairman and CEO; Leonard Jap III as a vice president, and his brother Steven Japp initially acting as the company’s potato buyer.

Then, in the space of a year, all three Leonard Japps died of natural causes. In 2004, Jays declared bankruptcy. A private equity group bought Jays and tried to make a go of it, but within three years Jays was bankrupt again. This time, snack company Snyder’s bought Jays, shut down the factory, and moved production to its own plants, slapping the Jays name on bags and shipping them back to Chicago.

Sun-Times reporter Mike Nolan attended the equipment auction at the Jays factory in 2008, where much of the machinery was being sold for scrap. “Numbered labels identifying the equipment being sold hung like toe tags in an industrial morgue,” he wrote.

For decades, Leonard Japp Sr. reported to work daily at the Jays factory on 99th and Cottage Grove. In later years Leonard Japp Sr. reported in a limousine, but report he did, inspecting the factory and picking things up off the floor himself. Many people loved Leonard Japp Sr., and many surely knew him better than Ronald Young, a Jays factory maintenance worker. Yet it was Mr. Young who offered the single most impressive accolade after Leonard Japp Sr. died in 2000:

“He always stopped to talk,” employee Ronald Young told the Tribune after Japp died. “He didn’t think he was better, and that just blew our minds. He earned our love that way.”

On Facebook, a woman whose father worked for Jays told me, “They had a golf outing every summer for all employees. Every employee got a prize no matter their score. Lots of prizes were very expensive, tvs, etc.” And, she said, there were employee dinners including families every year. “The Japps were very down to earth, generous people.”

Studs Terkel [1912-2008]

Studs Terkel was the uncle everyone wishes they had, sitting at the end of the table on family holidays with his rumpled white hair, rumpled shirt and loose tie, giving heck to stupid old curmudgeons and stupid young smart alecks alike--but in a way that doesn’t ruin dinner. Instead Uncle Studs actually gets everybody to debate something important all the way through dessert. People with wildly differing backgrounds and views actually hear each other, and learn something. Maybe you wish Uncle Studs didn't always have that cigar in his mouth, but you put up with it.

Studs Terkel was Chicago’s uncle. Like all beloved relatives, you can never replace him.

Child of the Depression, growing up in a boarding house run by Jewish parents who emigrated from Poland, Studs went on to graduate from the University of Chicago and then its law school. But he found his life’s work when he got hired by the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal program. In Chicago, the Writers’ Project also employed Nelson Algren, Saul Bellow, Gwendolyn Brooks, Margaret Walker and Richard Wright. Wow. There, Studs wrote and acted in plays and radio programs, going on to join a Chicago theater group and working in Chicago radio, including WGN. Somewhere in this period, depending on what story you hear, “Louis” Terkel got the nickname “Studs” from reading James T. Farrell’s famous Chicago novel, Studs Lonigan.

By 1950 Studs hosted Studs’ Place on the local NBC television affiliate, Channel 5. But after the network picked up Studs’ Place for national airing, as noted in this chapter, the show was canceled because Studs’ radical politics were too risky in a Communist-obsessed 1950s America. That led Studs to Chicago’s WFMT, a “fine arts” station that put him on the air for an hour every weekday at 11:00 a.m. Studs talked with everyone from Buster Keaton to Simone De Beauvoir. He started there in 1952 (the same year MAD Magazine began—coincidence?--they were both subversive for their day) and wrapped up 45 years later.

Studs was best known, best loved, and best of the best for talking to ordinary, everyday people. His incomparable oral histories, featuring unvarnished interviews with real Americans, started with Division Street in 1967. Go read some of Studs’ other masterpieces too, like The Good War, his Pulitzer Prize-winning oral history of World War II. Maybe more importantly, listen to Studs on your computer at The Studs Terkel Radio Archive.

Studs understood people, and he understood how important it was for people to know the past. That’s why he listened to so many people’s stories for so many years. I love this story Studs told about himself in an interview at Berkeley’s Institute of International Studies in 2003. It’s about Studs waiting at a bus stop near his Chicago home, and a wealthy young couple he often sees there. Studs says everyone in the neighborhood knows him and talks to him, but not these people. One day at the bus stop, he decides to make them talk to him:

There's a couple, I have to call them yuppies, because they are. Most young people are not. Most young are lost in the world, and wondering what ... but these two are. He's in Brooks Brothers, and he's got the fresh-minted Wall Street Journal under his arm. And she's a looker. She's got Bloomingdale, Neiman-Marcus clothes, the latest issue of Vanity Fair...The bus this day is late in coming. So I said, "I'm going to make conversation with them." So I say, "Labor Day's coming up." That is the worst thing I could possibly have said. He looks at me. He gave me that look that Noel Coward would give to a speck of dirt on a cuff, and he turns away.

Now I'm really hurt, you know, my ego is hurt. The bus is late in coming. So when I say something, I know it's going to get them mad. The imp of the perverse has me. And so I'm saying, "Labor Day, we used to march down State Street, UAW-CIO. 'Which side are you on?' 'Solidarity Forever.'" He turns to me and he says, "We despise unions." ....Suddenly, I fix him with my glittering eye like the ancient mariner, and I say, "How many hours a day do you work?" And he says, "Eight." He's caught! "Eight."

"How come you don't work eighteen hours a day? Your great grandparents [did]. You know why? Because in Chicago, back in 1886, four guys got hanged fighting for the eight-hour day -- it was the Haymarket affair -- for you." And I've got him pinned against the mailbox. He can't get away, you know. The bus [hasn't come], and he's all trembling and she's scared. She drops the Vanity Fair. I pick it up; I'm very gallant. I give her the Vanity Fair. No bus. Now I've got them pinned. "How many hours of week do you work?" He says, "Forty." "How come you don't work eighty hours, ninety hours? Because your grandparents [did], and because men and women got their heads busted fighting for you for the forty-hour week, back in the thirties."

By this time the bus comes; they rush on. I never saw them again. But I'll bet you ... See, they live in the condominium that faces the bus stop. And I'll bet you up on the 25th floor, she's looking out every day, and he says, "Is that old nut still down there?"

Royko on page 3.

Technically, Mike started out farther back than page 3 in the Daily News, in the op-ed section. And at first, the column appeared with a pen-and-ink drawing of Mike instead of a photograph. The drawing, frankly, looks pretty goofy to more modern eyes. He shifted to page 3 with a photo in 1966. Mike often claimed the column moved because a reader survey showed he got more readers in the op-ed section than the front-page stories. Also, later in the ‘70s, the Daily News sometimes ran Mike’s column horizontally across the top of page 3. We’ll cover Mike more in his own Optional History Chapter soon.

Co-Ed

Gil tells me that “co-ed” is what they used to call college students who were women, because women going to college in 1972 were still not just college students.

The Enema Bandit

Turns out the Enema Bandit didn't administer 10 forced enemas in 1972, as reported in the Sun-Times. Even in the Age of Newspapers, the newspapers were not always correct. But the reality is no better.

The Bandit had assaulted ten previous women who were alone in their Champaign-Urbana apartments, but the attacks dated back to1965. Michael Hubert Kenyon, the Enema Bandit—spoiler alert, he gets caught--began his anal spree while attending the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana. He continued his crimes in Kansas during 1970-72 while stationed there in the army, occasionally nipping back to Champaign and committing more assaults there too.

Kenyon came to the Chicago area to work as an auditor for the Illinois Department of Revenue at its suburban Lincolnwood office. He moved to Palatine, but visited Champaign and committed more crimes there all the way up to May 1975, a month before he was arrested for two 1974 home invasions in Glen Ellyn. There, he wore a ski mask and brought a sawed-off shotgun. He got away from one incident with a whopping $14.05 from three stewardesses, and skipped the enemas. But in May 1975 he also robbed two female college students in Wheaton—still identified as “co-eds” in the papers—and gave one of them an enema. Police said Kenyon had a speech impediment that “made his voice easily identifiable to his victims.”

Kenyon confessed and was sentenced to six concurrent terms of 6 to 12 years by an Urbana court—but just for the robberies. The assistant state’s attorney in charge of the case explained that the enemas weren’t covered by Illinois sexual assault laws, even though tying somebody up against their will, taking off at least their pants, forcing a rubber tube up their anus and filling their intestines with water is obviously a horrendous assault, even if it’s possible to think such an act could possibly not have sexual connotations.

Frank Zappa turned the sexual assault of multiple women into a comedic song entitled The Legend of the Illinois Enema Bandit, which appears on Zappa’s 1976 live album, Zappa in New York. It’s a bluesy ballad you may be able to view in a live performance at the Palladium in 1981 on YouTube. I’ve embedded the link below—we’ll see if the video or YouTube still exist as you read this. Another band member starts the song while Zappa plays lead guitar. It’s presented as a big joke, which admittedly is the normal Zappa attitude. Around the six-minute mark, Zappa takes the microphone. He’s repeating many of the same lyrics, in the same mocking manner, as his band member. But since Frank wrote the song, we’ll concentrate on his portion of the performance here.

Zappa chuckles and mugs his way through. The lyrics include:

Lord, the pitiful screams

Of all them college-educated women….

Boy, he’d just be tyin’ ‘em up

(They’d be all bound down!)

Just be pumpin’ every one of ‘em up with all the bag fulla

The Illinois Enema Bandit Juice

Bandit, did you do these deeds?

The Bandit say, ‘It must be just what they all needs’

That last line is especially striking, because it’s used as a special repeating refrain during one of the excruciatingly long tuneless segments of the song so typical of the Zappa oeuvre.

Zappa told one interviewer that he heard about the Enema Bandit on the car radio while driving between gigs in central Illinois. Zappa called it “the chance to do a folk song” because “(h)e’s like a household word here, and he should have a song.”

If you watch the YouTube video, note the brief camera cut to a female audience member at :37-:38, which includes the part about the “pitiful screams” of college-educated women. The look on the female audience member’s face clearly says: “Wait a minute—what the fuck?” Nobody else seems to think about it.

One of the Enema Bandit’s victims from 1971 went on to become an acclaimed and beloved fourth-grade teacher at an Urbana elementary school. The Enema Bandit was a local joke to many, she told Rebecca Mabry of the Champaign News-Gazette in 2009. “But it was never a joke to me,” she said. “And sometimes when I talk about it I start shaking. And that was 1971. I started teaching that fall.”

When I told Gil about the Enema Bandit, he scolded me again for losing focus and wasting time. But then he stopped and got an odd look on his face.

“Wait a minute,” said Gil. “When did that happen again?”

I told him: The Enema Bandit started his assaults in 1965, and then he attacked someone at least every year after that for a decade.

“Wow,” said Gil. “Are you serious? And they thought that was funny?”

Then Gil told me what he was thinking: The Enema Bandit tied up and assaulted his first female student victims contemporaneously and only a few hours away from one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century. The young female students were tied up first.

Late Wednesday night July 13, 1966, Richard Speck broke into a Chicago townhouse at 2319 E. 100th Street in the quiet Jeffrey Manor neighborhood—just east of Roseland, across the geographical obstructions of the Calumet Expressway (I-94, now the Bishop Ford Expressway) and Lake Calumet.

Speck forced the nine young women student nurses from South Chicago Community Hospital who lived there into two upstairs bedroom. He used a knife to tear up their bedsheets into strips, then tied them up and gagged them. A police detective later told the Tribune the knots were professionally done, so tight he had to cut them off. Finally Speck led eight of the women out of the bedrooms one by one, and stabbed or strangled each. Many of the women were both stabbed and strangled.

Speck raped his last victim before strangling her. One nurse, Corazon Amarau, survived by rolling underneath a bunkbed and hiding. Apparently Speck lost count, because he left her behind.

One victim, 20-year-old Patricia Matusek, was from Roseland.

That doesn’t make Patricia Matusek more important than the other women. But because Steve grew up in Roseland, where nearly everyone either knew Patricia Matusek or knew someone who knew her, the Speck murders loomed especially large in the background of his childhood. I’ll focus on Patricia Matusek and her family as we go on here, but that focus isn’t meant to pass over the eight other nurses. Rather, I hope reading about Patricia Matusek makes all these women—and the victims of the Enema Bandit—feel as real as your own sister or best friend.

Gil says he’ll never forget seeing the Daily News on a newsstand Thursday afternoon, with the smiling pictures of all eight murdered student nurses lined up on the front page like a high school yearbook.

They are, on the top row, from left to right: Gloria Duffy; Mary Ann Jordan; Suzanne Farris; and Valentina Pasion. On the bottom row: Patricia Matusek, Merlita Gargullo, Pamela Wilkening; and Nina Schmale.

Opening the paper was almost worse, Gil said, because reading the details of the crime scene was shattering. “I remember the papers all said the first cop on the scene said the bodies were piled up like in a Nazi death camp,” he said. All the papers also noted that it was the worst mass murder in Chicago history, bigger than the 1929 Valentine’s Day Massacre, when Al Capone’s mobsters killed seven of rival Bugs Moran’s men.

Corazon Amarau managed to free herself but stayed under the bunkbed all night, not knowing if Speck had left. Early Thursday morning, she crawled out, found her slain roommates, and kicked out a screen in the upstairs bedroom window to get out onto a large window ledge. Her screams alerted neighbors about 6 a.m. Within minutes, a dozen police cars had arrived, and by 7 a.m. the news broke on Chicago radios.

We can assume Wally Phillips on WGN may have been first with the story, but if not, his producers would have picked it up from another station or the police immediately. Wally alone would have broadcast the news to 25% of everyone listening to a radio in Chicagoland.

“Coroner Toman’s calling the murder of 8 nurses ‘the crime of the century’ was not an emotional outburst set off by the sight of 8 bodies in the nurses’ home,” wrote Jack Mabley, star columnist of the afternoon Chicago’s American, later that day. “Perhaps no single crime in American history matches this for senseless carnage. The impact of the news on the 6 million people in the Chicago community was immediate and intense. Within hours of the discovery of the bodies, virtually every Chicagoan knew about the tragedy. On buses and trains, in offices, on street corners, in kitchens it was discussed in hushed and unbelieving words.” (Mike Royko—who got his Daily News column because Mabley jumped to the American—wasn’t in the paper that week, presumably on vacation.)

Friday’s Daily News ran a heart-wrenching, eloquent meditation by one of its most distinguished writers, M.W. Newman: “The mind boggles at mass murder,” he wrote. “Where does it end and outright war begin? How could one man kill eight girls in a civilized neighborhood where the sky still is open and every house has a lawn? ‘The girls’ bodies were stacked like cordwood,’ said a shaken homicide detective as he struggled for an answer to those terrible questions. ‘Like cordwood.’”

That Thursday morning the neighbors, Newman wrote, “clustered restlessly, many holding transistor radios to their ears, straining for news reports of the murder the way baseball fans sometimes tune in to the game while sitting at the ballpark.”

Patricia Matusek had spent the previous two days and nights at home with her family at 10815 S. Michigan Ave.—Joe Matusek’s Club, a tavern, on the ground floor, and the Matusek family home upstairs. Pat was tired after the long hours at the hospital, and wanted to stay home Wednesday night too, but hospital rules required her back at the townhouse by 10:30 PM, so a friend drove her back.

Thursday morning, Pat’s mom, Bessie Matusek, heard the news on the radio. She woke up her husband. “I felt a chill go down my spine,” Joe Matusek told reporters later. He dressed and drove to the townhouse to find out if Pat was alright. South Chicago Community Hospital operated three townhouses for their student nurses, so there was no telling with the sketchy news reports.

Joe Matusek got there in time to see two Chicago cops carry Pat’s body out of the townhouse on a stretcher, covered by a blanket. According to one Tribune article, hundreds of neighbors were crowded along the sidewalks by then, and blood dripped onto the sidewalk as the police carried some stretchers out of the townhouse.

Another Tribune article described Joe Matusek’s experience:

He watched as two policemen carried out the covered body of his daughter. Tears ran down his cheeks, and his lips quivered until he bit them.

The shocked father worked his way into a group of newsmen surrounding Andrew C. Toman, Cook county coroner. He heard Toman describe the cause of his daughter’s death.

“Patricia A. Matusek died of asphyxiation by strangulation,” Toman said. “Her wrists were tied behind her with a piece of sheet. She was found lying on the bedroom floor.”

At the time, no one knew who Matusek was. A television man tried to shove him to get closer to Toman.

“Get out of the way, this is for the press,” the television man said.

“I’m the father of one of the girls,” Matusek replied. “I want to hear how she died.”

The television man apologized and turned away.

“My daughter was to be graduated in August,” the saddened father said. “Pat was going to work at Children’s Memorial hospital. She had an interview last week and was accepted.”

The papers would carry a heartbreaking picture of Joe Matusek, outside the house where his daughter died. “He looked a lot like Dick Butkus, y’know?” said Gil, his eyes shifting to the side as he looked into the gloom of the microfilm room, remembering Joe Matusek. “Like a middle-aged Dick Butkus, but still with the ‘60s crewcut.”

Rosemary Sobol wrote a wonderful story for the Tribune in 2016 on the 50th anniversary of the murders, focusing on the young nurses, where the attention of course should be. She describes John Schmale, older brother of Nina Schmale, finding an old box of Kodak slides in his basement labeled “Nina South Chicago Hospital”.

Schmale set up his old slide projector. “Clicking from slide to slide, Schmale stepped into his sister's vanished world. It was a world of hair curlers, hair spray cans, ashtrays, manual typewriters, textbooks, sheath dresses, corsages, cluttered rooms, a place where young women laughed, hugged, studied, ate, teased each other's hair.”

Sobol introduces us to Pat Matusek, and she is unforgettable.

Often after a day of classes at Fenger High School, Pat Matusek walked to Roseland Community Hospital to see her cousin Tommy.

She was 14. He was 15. He was dying.

She'd bring him water, fluff his pillow, hold his hand, tell him that she loved him. On many of those days she walked home crying, yet it was her afternoons with Tommy that made her think she could be a nurse.

Pat’s best friend, Arlene, lived next door above her family’s business, a funeral home. “Between their second-floor apartments stretched a low, flat roof, and Pat and Arlene often ran across it to tap on each other’s windows, looking for a playmate,” writes Sobol. Pat would be waked in Arlene’s family’s funeral home, with a funeral mass at her family’s parish, Holy Rosary Catholic Church.

Speck was caught within three days thanks to Corazon Amarau, who despite her trauma gave a full description of Speck to police by 6:30 a.m. that morning. Then, a massive effort by Chicago police and an emergency room doctor finished the hunt. Detectives canvassed the neighborhood, ringing doorbells, talking to everyone—and they understood that the nearby Calumet Port and the National Maritime Union Hall directly across the street from the nurses’ townhouse meant a merchant seaman might be involved. Speck was a merchant seaman who’d missed his ship. He was waiting around the area for a new gig.

In 1986, Dennis L. Breo wrote a comprehensive look back on the killings for the Tribune and described the hunt. By 11 a.m. Thursday, police had put together the pieces to name the murderer, and obtained a picture of Speck from the Coast Guard. Later, when the detectives got confirmation that Speck’s fingerprints matched those left on the townhouse windowsill, “We all cried like babies,” Detective Edward Wiolosinski told Breo. “We had our man.”

Chicago Police Supt. Orlando Wilson held a press conference on July 16, telling the world that the suspect had 13 tattoos, including “Born to raise hell” on his left forearm.

Late that night, a man with gashes in both arms was brought to the Cook County Hospital emergency room. Speck had tried to kill himself. First-year resident Dr. Leroy Smith was eating dinner across the street as he read the newspaper accounts of Supt. Orlando’s press conference, when he was paged to come back to the emergency room for a new patient. Smith thought he recognized Speck, and stepped back to re-check his newspaper, left nearby.

“I brought the paper back with me and began to scrub the blood off Speck’s arms,” Smith told Breo 20 years later. “As I wiped the blood from the left arm, I saw the ‘B’ first and the rest of ‘Born to raise hell.’….Speck’s pressure was 70/0 and mine must have been 270/150.”

Breo recounts that Smith went back to Speck and asked his name. Speck answered “Brian.” “I grabbed him by the back of the neck—there’s a major spinal accessory nerve there near the trapezius muscle—and I squeezed hard, real hard. ‘What’s your name?’ He answered: ‘Speck. Richard Speck.’ Speck gasped ‘Water…water.’ I said, ‘Did you give the nurses water?’ I let some ice cubes drip into his mouth.”

Breo also spoke with Marilyn Farris McNulty, student nurse Suzanne Farris’ older sister. McNulty told Breo she wasn’t speaking 20 years later to just say “‘Hey world, something terrible happened 20 years ago and some of us are still alive to talk bout it.’ No, I want some good purpose to come of it. I want people to know that we were all totally destroyed by this and that he—I still cannot bring myself to say his name—that he killed more than Susie and the other nurses. It should never be forgotten that he killed a little bit of all of us.”

It would be impossible to overstate how terrorized Chicagoans were by a crime of this savagery, against young women planning to spend their lives helping and healing others, in the safety of their own home—especially during the first days afterward, while a psychotic killer was on the loose. “I had my first experience with evil in the world 50 years ago when I was 12,” wrote Cory Franklin in the Tribune in 2016. Franklin, a frequent Tribune op-ed contributor, headed Cook County Hospital’s Intensive Care for 25 years. In 1966, he was a youngster on the North Shore, about as far as you can get from Chicago’s Far South Side and remain in the Chicagoland area—but for him, for everyone, the Speck murders were local, as if they happened next door.

Franklin snagged a summer gig paying $1 a day “to wrap copies of the afternoon Chicago Daily News, ride in an old Pontiac with a delivery guy and throw papers on the lawns of a new suburban subdivision.”

Most unsettling was that front page I wrapped over and over again; it carried a police artist's sketch of the killer, created through details provided by the plucky young nurse who rolled under a bed and remained there all night, lying near the bodies of her lifeless friends.

The sketch was indelibly etched in my mind -- a man with a crew cut and a thin, tapering face devoid of emotion, and cold, menacing eyes. That such a predator lurked somewhere chilled me to my bones.

That day, unnerved, I threw papers on the roofs of my first two houses. I didn't get paid, and it appeared I wasn't long for the job.

Twenty-five years later, Dr. Cory Franklin was called to treat a visiting ailing prisoner at Cook County Hospital—Richard Speck. “Before I sent him to the cardiac unit, he made some cheap, sarcastic remark that bespoke pure evil. I sensed no remorse in his taunting smile,” wrote Franklin.*

Joe Matusek retired from running his tavern in 1980, but he never retired from making sure Richard Speck stayed in prison. Speck was sentenced to up to 1,200 years, but he still came up for parole every few years. Joe Matusek would not miss a parole hearing, even after he began to walk with canes and then use a wheelchair. He died on Pat’s birthday, in 1990. “He hung on long enough to be here for that day,” Bessie Matusek told the Tribune.

“It broke my heart,” said Gil. “It broke everybody’s hearts. Not just Chicago, the whole country. After that, I don’t know how you joke about somebody breaking into a home and tying up young women students. It’s a pretty sick world.”

*Cory Franklin wrote a memoir of his years at Cook County Hospital in 2016: "Cook County ICU: 30 Years Of Unforgettable Patients and Odd Cases."

NEXT UP, Chapter Three Notes Part B: Chicago Newspapers

SUBSCRIBE

If you’re not immediately repelled, why not subscribe? It’s free, after all. You’ll receive a new chapter monthly via email, and find out why I am spending so much time on the story of this one guy. You’ll also get a weekly compilation of the daily items on social media: THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, and MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY.

And why not SHARE?

Maybe you know someone else who would enjoy reading about a ten-year-old Italian-American kid on the South Side of Chicago in 1972. Didn’t your parents teach you to share?

We’d love to hear from you.

3