To access all site contents, click on the rose icon in the upper left corner or HERE.

Why do we run this separate item, Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today? Because Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the serialized novel central to this Substack, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” lived in a Daily News household. The Bertoluccis subscribed to the Daily News, and back then everybody read the paper, even kids. And if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko. Get your Royko fix on Twitter too— @RoselandChi1972.

July 10, 1972

“MIAMI BEACH—George Meany dropped it into our conversation so casually that at first I couldn’t believe he was really saying it.”

It’s Mike’s first column from the 1972 Democratic National Convention.

“For a half an hour, he had been sitting across the table, lambasting the candidacy of George McGovern, but denying that he came here to lead the stop-McGovern movement. Nothing he said was new…. McGovern’s reform rules are foolish; McGovern can’t win; McGovern’s no friend of the working man….and he (Meany) has never even chatted about politics with his fellow old-guard politician, Mayor Daley.”

For Younger Readers: George Meany’s power may have been waning in 1972 as Mayor Daley’s was, but both had plenty of punch left in them. Let’s take a look.

George Meany \ ˈjȯrj\ \ ˈmē-nē\: 20th century big shot labor leader, started out as a plumber from the Bronx. Time Magazine’s 1980 obituary noted that news stories so often referred to him as “Crusty George Meany” that he once said, “Don't they know my first name isn't Crusty?”

President of American Federation of Labor (AFL), 1952-55. Engineered AFL’s merger with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), then served as AFL-CIO’s first president 1955-79, representing up to 111 unions and 17 million workers at a time. Here’s Meany’s speech to the first AFL-CIO convention in 1955. And here he is in 1952 talking about the AFL backing a presidential candidate for the first time—Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson.

Anti-Communist stance on the level of General Jack D. Ripper.

Not only did Meany not oppose the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act’s requirement for labor leaders to sign loyalty oaths against Communism, he said he’d “go further and sign an affidavit that I was never a comrade to the comrades”.

Meany’s Associated Press obituary called Title VII of the 1965 Civil Rights Act, which bars employment discrimination, “perhaps his greatest legislative accomplishment”. However, Meany is particularly known in 1972 for supporting the Vietnam War, from LBJ through President Nixon, plus despising the ‘60s/’70s New Left. Here’s a great quote that I can’t verify from Wikipedia re the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention, but too good to pass up: “Meany sided with the police by calling the protesters a ‘dirtynecked and dirty-mouthed group of kooks’”.

No surprise, Meany is a leading opponent of nominating Sen. George McGovern as the 1972 Democratic presidential candidate.

Still, Meany is more complicated than all that sounds. The AP noted that Meany was “the first national figure to call for Nixon’s impeachment” in 1974, admitting “he was wrong to support the Viet Nam War.”

Meany also worked against union corruption and organized crime influence. Per Time, “If he lacked the missionary fervor of a Eugene Debs (“Ideology is baloney,” Meany scoffed) or the organizing zeal of a Samuel Gompers, he clung with consistency to his conviction that no nation could be free if its trade unions are shackled. Meany fought hard for the basics: higher wages, shorter hours, safer working conditions, and limits on corporate profits in any wage-price control plan.” Meany expelled corrupt unions from the AFL-CIO, including the Teamsters. So he was not buddies with Jimmy Hoffa.

“One of the beauties of a free society is that you can disagree with a man on just about every conceivable issue and still recognize the essential role that he has played in the country,” the Chicago Tribune editorial board wrote after Meany’s death. “George Meany was such a man.”

However, the Tribune went on to claim that Meany’s answer for all problems was “more spending and higher pay,” so that Meany and the labor movement had transformed labor from “being the oppressed” to “in many ways…the oppressor.”

But the Trib editorial board concluded:

“Meanwhile we’ll miss Mr. Meany’s cigar and his scowl and his dry wit….But we’ll miss him also as a man who was never devious, who was highly patriotic, and who devoted his life to the conviction that the workingman can prosper best in a country that is free.”

It’s interesting that the Tribune, generally an opponent of George Meany, specifically described him as “not devious,”— because “devious” is exactly what Mike believed him to be at the 1972 Democratic convention.

Mike had chatted with Meany for a half hour. “All the while, his five gin rummy-playing cronies” were sitting nearby and chuckling “at his jibes” and “puffing on cigars”.

“Then Meany got a reflective look on his face, tapped the ash from his stogie, and said:

“‘You know, I’ll give McGovern credit for accomplishing one thing.’

“What’s that?

“‘Ten years ago, he was broke. Now he’s got a big house, expensive works of art, a swimming pool, a vacation home, a big bank account. He’s done all right for himself.

“Meany paused for a long moment then said:

“‘I wonder where he got it all? That would be something for somebody to look into, where he got it all.’”

And right away, Meany got up from the table and left.

Mike knows why, and explains it to his readers:

“When you drop that kind of thing, you always end the conversation right then and there. Timing is important, when you are delivering one of the oldest, dirtiest, political groin-kicks.”

Mike knows that Meany, like so many others before, “floated that kind of balloon” hoping a reporter would print it without investigating. “I wonder where he got it all?”

“Until that moment, I had felt impartial about this convention,” writes Mike. “My impartiality has even put me in the unfamiliar and uncomfortable position of having sided with Daley’s coat holders in their fight with the Singer 59. (See Mike on July 6, when he wrote that he would have voted for Daley’s delegates to represent Chicago at the Democratic National Convention, and also July 5 and 7.)

“But Meany’s cheap stunt—which reminds me so much of Chicago-style politics—has shoved me towards McGovern’s corner. If the cigar-chompers have reached the point where they have to use the whispering-campaign approach, maybe we do need a new politics.”

Mike does some back-of-the-envelope math after speaking with Pierre Salinger, the old JFK standby now with McGovern, about how much McGovern might make from speaking fees. Mike figures McGovern must make a bit over $100,000 annually, which in 2022 is almost $700,000.

“And if Mr. Meany wants something more specific, he should be the one to ask the questions,” Mike concludes. “If you want to play politics at its dirtiest level, don’t ask me to dive into the mud for you.”

July 11, 1972

As always, Mike pinpoints the heart of this story with this lede:

“Many months ago, when he was warned that it might happen, Mayor Daley said something like: ‘Who in the hell is going to throw us out?’

“At 2:30 this morning, he found out who.

“With a throaty roar, the red-eyed delegates threw Richard J. Daley of Chicago out of the Democratic National Convention.

See this week’s THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 for the frenzied, astonished news coverage of Mayor Daley’s dumping, and an explainer for background.

“For the first time since 1924, when he was a coat-holder for Big Joe McDonough of Bridgeport, Daley won’t attend a Democratic convention in some capacity—onlooker, delegate or king-maker,” writes Mike.

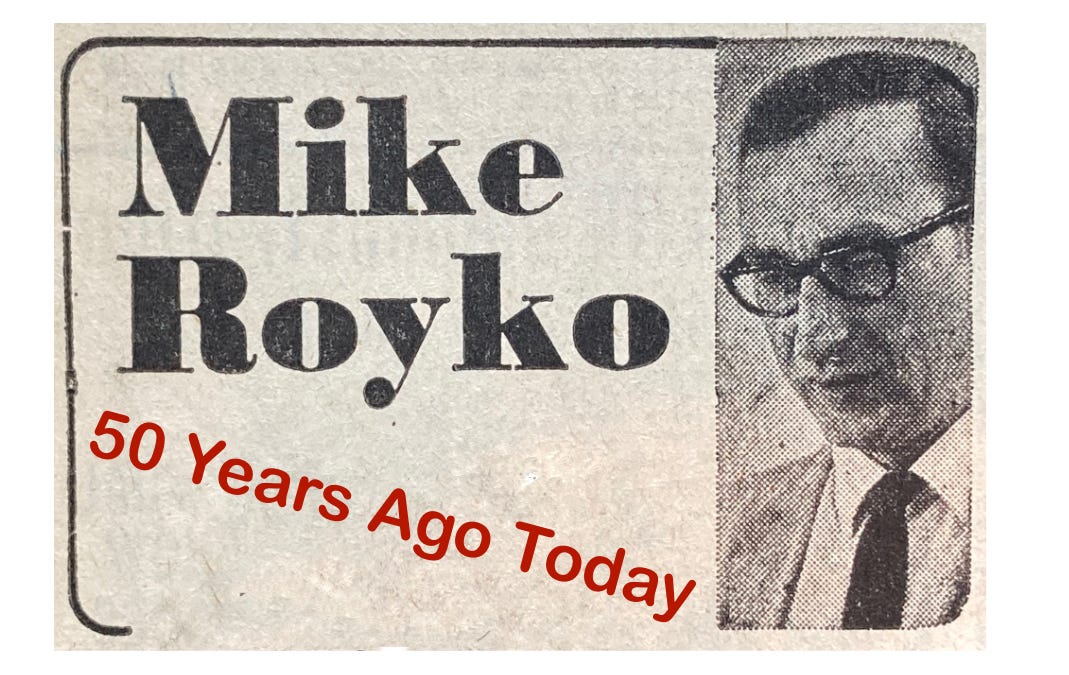

Mike is just sorry it all happened so late at night that hardly anyone saw the “fine entertainment,” including “beautiful movie star” Shirley MacLaine getting up to the convention rostrum to rally the convention to expel Cook County Coroner Andrew Toman of all people.

“Toman, a white-haired cadaver-counter, was probably thrilled,” writes Mike.

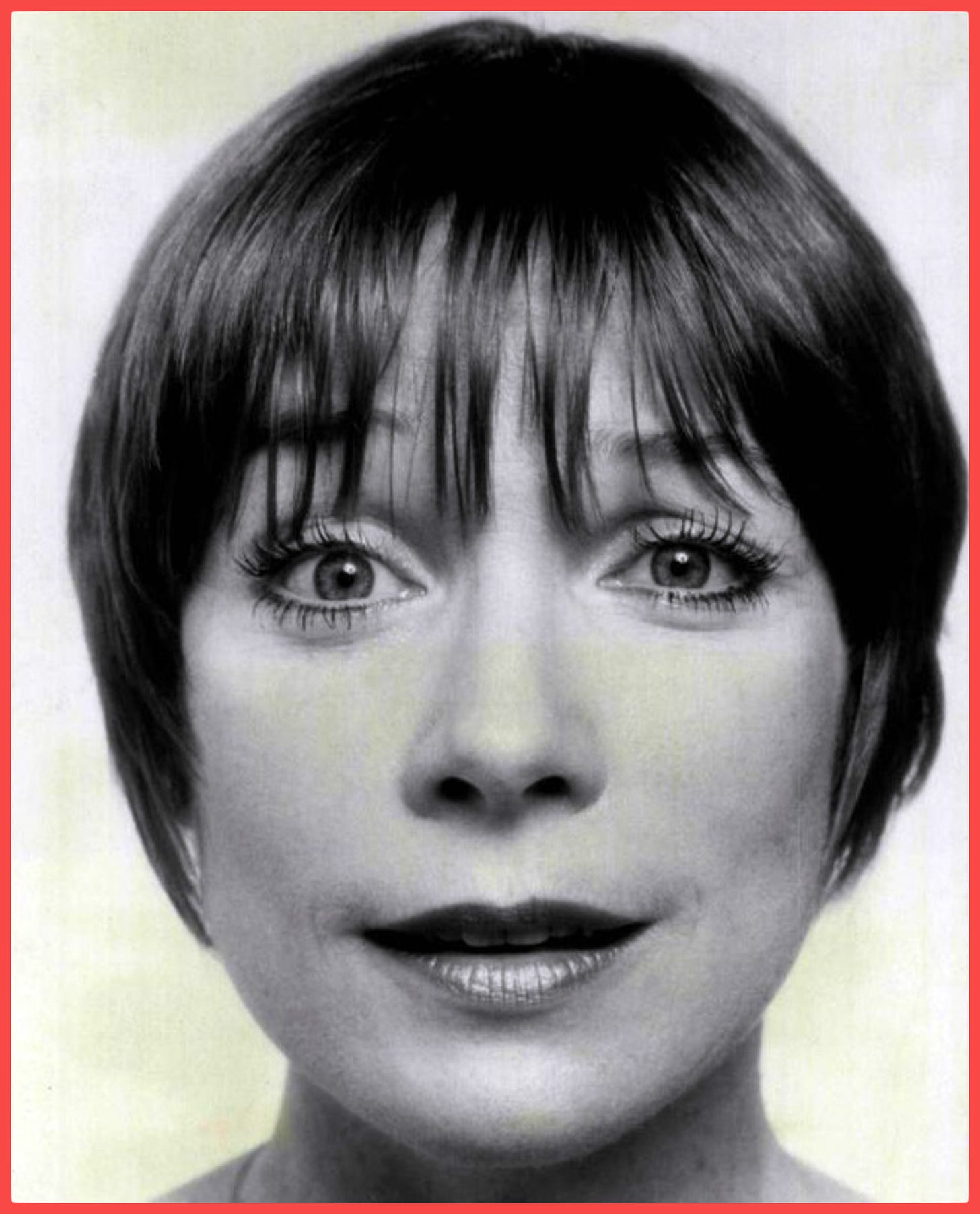

But soon Mike gets down to more analysis. He describes Rev. Jesse Jackson as the guy who really brought home the bacon for the slate of independent Democrats looking to replace Mayor Daley’s elected delegates at the convention, in a room-shaking speech.

“He hit the convention where it is at—in its own identity,” writes Mike. “He poured it on, about how Daley’s delegation didn’t have enough women, enough Latins, enough blacks, enough young people. Since the building was packed with women, with Latins and blacks, and with young people, they naturally shared Jackson’s indignation. That the Singer-Jackson delegation is short on white ethnics, older people and working-class people was ignored.

“Jackson brought them to their feet, screaming for total victory. Then he loped back to the convention floor to try for an expedient compromise that would keep Daley at the convention, despite his many sins.”

But, Mike says, “It could not have turned out any other way. It would have been unthinkable for Daley to have sat down with Singer’s reformers. That would have made them his equals, and he wouldn’t want to do that for his Chicago political enemies.

“At the same time, McGovern could not sacrifice Singer’s delegation completely, or his integrity would have been laughable.”

Still, as soon as the cheering stopped, Mike says the smarter Democrats realized they don’t know if a Democratic presidential candidate can win Illinois without Mayor Daley.

And even the Machine, writes Mike, can’t know if it can elect its own people without supporting the guy at the top of the ticket.

“My guess is that they can do enough damage to McGovern so that they can survive but he can’t win Illinois,” Mike concludes.

“But that’s only a guess. Maybe Jesse Jackson will prove me wrong. Maybe he will get out that big Chicago vote for McGovern. Maybe Jackson will even vote for himself.”

DON’T MISS ALL THE 1972 DEMOCRATIC CONVENTION COVERAGE AT TCD1972!

July 12, 1972

With the really important issue settled at the 1972 Democratic National Convention—Mayor Daley—the party moved closer toward nominating a candidate for president.

Today, Mike describes the convention appearance of Alabama Gov. George Wallace, who was shot by a would-be assassin on May 15 at a Maryland shopping plaza during a campaign appearance.

“Wallace fell to the ground and blood began to pour out of the right side of his chest,” wrote the Daily News’ Robert Gruenberg at that time. Wallace survived, but it was understood immediately that he would be paralyzed for life.

Wallace was notorious for his opposition to desegregation, including his gubernatorial inaugural declaration, “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” During his first term as governor, Wallace stood in the doorway of a University of Alabama building to physically block Black students from entering.

When Wallace was shot, he was doing well enough in the Democratic presidential race that some people feared a Wallace nomination. Wallace won the Michigan and Maryland primaries after the assassination attempt. But his reception at the convention doesn’t suggest his earlier successes.

Wallace was pushed to the convention stage in a wheelchair, writes Mike, “then lifted up, chair and all, so from the floor it appeared that he was standing.”

“When he came in, the band began playing a rousing tune. In such moments, conventions can go crazy. But you don’t often see them as indifferent as this one was.”

“Most people stood up, but that was all they did. Off in the distance, the Texas delegation and a few other Southern groups jumped and waved signs and cheered. But that just emphasized how many others were silent.”

….. “Wallace pretended not to notice. He kept saluting his pitifully small number of supporters whose cheers sounded feeble in the huge hall….Even from a distance, the effects of the assassination were obvious.”

As for Wallace’s speech, it was the same as his campaign material—perhaps “more moderate than a few years ago, when his race-baiting wasn’t at all concealed.”

Wallace’s delivery was flat, and he was tuckered out after ten minutes. “The swagger and sharp edge were blasted out of him in the shopping center, probably forever.”

Most delegates didn’t bother standing again as Wallace was wheeled away.

“You might consider that rude,” writes Mike, “but many of the people at this convention were in Alabama during the mid-1960s when murder was an accepted tactic for keeping uppity people in their place and Wallace was Alabama’s symbol.”

…. “They booted Daley on Monday and yawned at Wallace on Tuesday. It’s a new party,” Mike concludes. “I don’t know if it can win, but it has raised its standards.”

July 13, 1972

“MIAMI BEACH—It happened exactly at midnight, and sitting there in the convention hall, I felt proud,” writes Mike. “Not just because it was the Illinois delegation that put George McGovern over the top, but because it was our state Rep. Clyde Choate who spoke the thrilling words into the microphone, touching off the bedlam.”

Clyde Choate is the subject of Mike Royko’s Nov. 9, 1972 column, which I compared favorably to Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” It’s about Choate, a bona fide World War II hero with a Medal Honor, who joined the Illinois Legislature and got chummy with now-deceased Illinois Secretary of State Paul Powell. You might remember Powell as the guy whose hotel room closet was found to contain about $750,000 in small bills, including a large sum in a shoebox. Powell’s lasting scandal legacy includes shady racetrack stock he also owned, which former Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner is now indicted for. See Jan. 1-2 for a fun explainer on all that. Clyde Choate also owns thousands of shares of that shady racetrack stock. Choate didn’t like Mike’s Nov. 9 column, which led to Mike’s Nov. 16, 1971 column, “Punch me in the nose!?”

Mike’s proud to have a prominent member of the “racetrack-scandal crowd” still in place, representing the state. After the Singer 59 got Mayor Daley kicked out, in a bid for unity, they supported Choate to lead the Illinois delegation.

“Illinois’ reputation for political color is not completely gone when its delegation is led by the prize pupil and protege of Paul (Shoebox) Powell,” says Mike.

“There were other encouraging signs that the new Democratic Party has retained some of the old traditions,” Mike goes on. “One old tradition is that a party believes the history of all evil can be traced back to the day the other party seized office. This, coupled with the belief that all goodness begins the day you take office, accounts for the way most political speeches sound.”

Example: A Wednesday speech had one politician yelling about how the Republicans haven’t ended the Vietnam War. Huge applause.

“I waited for him to yell how Lyndon Johnson hadn’t ended it, either, and had even made it bigger, because I wanted something to cheer about, too.”

As for nominee Sen. George McGovern, Mike heard him at the convention “hailed as ‘a man of great vision and courage,’ as well as ‘a man who shown he’s a winner,’ and ‘a man of conscience and courage”.

“I hope he has all those qualities,” writes Mike.

“But I’ve heard the same things said about the last several Presidents, too, and this time I would happily settle for someone about whom it can be said, with 100-per cent assurance, that:

“He is a man who won’t mess things up.”

July 14, 1972

As Mike waits to hear George McGovern give his acceptance speech for the presidential nomination at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, he remembers seeing McGovern two years earlier at a VFW in Chicago Heights.

Mike felt sorry for him.

Mike was there for Illinois state Rep. Tony Scariano’s fundraiser. He calls Scariano a friend, who “asked me to introduce the politicians with insults, which I accepted as a sacred duty.”

But Mike couldn’t think of any insults for McGovern, because he just felt sorry for this poor schmuck forced to hang out in the south suburbs two years before an election, trying to scare up some points “to add a fraction of a fraction of a point to his wispy support.” Kennedy, Johnson, Muskie and Humphrey didn’t have to do that, Mike figured.

Now Mike realizes that George McGovern was simply “doing what old-time politicians used to do so well before they became complacent and let it slip. He was gathering up the votes, here and there, a few at a time.”

And, of course, it worked.

AFL-CIO president George Meany—see his definition under July 10 above—says George McGovern and his supporters have created a shambles, writes Mike. “But his definition of a shambles must be any situation in which he can’t point his cigar at a grateful candidate and say: ‘You’re it.’”

“The worst shambles I’ve seen in politics was not—as McGovern’s enemies are saying—the year Goldwater’s people took over the Republican Party. Instead it was 1968 in Chicago. That shambles was a gift from Richard J. Daley and Lyndon B. Johnson, who virtually handed the election to Richard Nixon. Now they are crying that McGovern has snatched their party away from them and is ruining it.”

“Maybe that’s how they see it,” writes Mike. “But I see a man who took as many of the broken pieces as he could find and put them together.”

Mike also thinks the convention isn’t a shambles as far as the delegates go.

“For years, the Democratic Party milked the black vote. In return it provided handouts in the form of welfare, and civil rights laws that people had coming anyway. But it didn’t give them a voice. Now they are getting it. I don’t see anything ‘divisive’ about that.’”

…. “The most significant new faces are those of women.”

“There’s truth in the complaint that McGovern’s organization and his delegates are short on blue-collar workers, union members and the kind of people who were called ‘the silent majority,” Mike observes, without mentioning that he has been one of the more prominent voices to point that out.

“Whose fault is it if people prefer being silent to speaking up? Who says they have to endlessly watch pro football, instead of a few political debates?”

Mike considers that for the last twenty years or so, people have been finding more and more leisure activities. “But many have found that fun and games aren’t enough,” he writes. “They have found that they can’t identify with a quarterback who peddles shaving lotion.

“Now, they are finding that politics gives them something they can actually do, and feel they are part of something….For this, they are being called elites. I don’t know what that means. If it means somebody who takes an active interest in the course of his country, then they are elites. But those who slump on the sidelines I call vegetables.”

Mike admits he’s made fun of Shirly MacLaine—he sure has—but he admits she’s been working hard at the convention, organizing.

“And I find her less elite than millionaire Bob Hope, a joke-maker using his dough for the Republicans or Spiro Agnew hobnobbing with Frank Sinatra and Zsa Zsa.”

“When they say elitists, I think about Ald. Anna Langford, a McGovern delegate, and I have to laugh.

“Ms. Langford is a brilliant and humane black woman, born poor, who put herself through law school late in life, barged into politics, and got herself elected to public office in Chicago.

“If that background makes Anna Langford an elitist, then so was Abe Lincoln.”

As we here all know, weekends could be sad for a Daily News family because Mike Royko wasn’t in the Daily News’ single weekend edition. So we look for Mike elsewhere on weekends.

In honor of Mike’s abiding fondness for writing about Clyde Choate, let’s look at moment for which Clyde Choate would become most famous. Mike mentions it in his July 13 column, but I didn’t include it there. By the way, besides partaking in the shady racetrack stock for which former Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner will go to jail, the other thing to know about Clyde Choate is that he is from Anna in downstate Illinois.

“Choate even added a fine touch of zaniness during the moments he announced the Illinois vote,” Mike wrote. “He prefaced the vote by saying that Illinois has ‘banned the use of lettuce.’

“Not eating lettuce has become a very big issue at the Democratic convention, just as not eating California grapes was popular among liberals some time ago.

“State after state, delegations have announced at various points that they are joining in the boycott. When candidates were put in nomination, among the signs bearing their names were other signs saying: ‘Boycott lettuce.’ A foreign visitor might have thought that one of the front-runners for the nomination was named Boycott Lettuce.

“But only Choate said that his state was ‘banning the use’ of lettuce, rather than merely urging that it be boycotted.

“After he said it, several reporters pondered the remark and one of them finally concluded:

“‘It is exactly midnight, and Choate has turned into a bumpkin.”

Immediately below Mike’s column on July 13, the Daily News ran the above headline with an article by Karen Hasman.

“It probably came as a great surprise to many Illinois residents to learn that there is a consumer boycott of head lettuce here.

“The boycott became an instant ‘in’ cause this week at the Democratic National Convention. Even state Rep. Clyde Choate (Anna), chairman of the Illinois delegation at the convention, stood up and expressed his support for the national lettuce boycott.

“On network TV, Choate announced:

“‘Illinois has banned the use of lettuce.’

“His comments were taken as a sign of growing support for a faltering boycott conducted by the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee.” That’s the union run, of course, by Caesar Chavez—a student of Chicago’s own Saul Alinsky.

Hasman reports that when the Illinois delegation caucused together, the Singer-Jackson delegates introduced a lettuce resolution to support the Farm Workers boycott, which began in September 1970 “to force lettuce growers to negotiate with the union. The boycott was called off in early 1971, then renewed again last March. Until now, however, the lettuce boycott did not have the publicity of a grape boycott successfully carried out by the Farm Workers.”

The Chicago Tribune wrote an editorial about the “lettuce ban” on July 16:

“One of the more startling episodes of the Democratic convention was to hear Sen. Ted Kennedy greet the delegates not only as fellow Democrats but as ‘fellow lettuce boycotters,’” writes the Tribune editorial board. “Earlier in the show, several state delegation chairmen had proclaimed their support of the lettuce boycott while announcing their vote tallies. Illinois Chairman Clyde Choate used a broader brush when he declared over network TV that Illinois was joining other states ‘that ban lettuce.’”

The Tribune points out that Chavez’s Farm Workers belong go the AFL-CIO, and its lettuce boycott is largely a dispute over the fact that the rival Teamsters have contracts to harvest about 70% of all California lettuce (which is almost all U.S. lettuce), while Chavez’s Farm Workers have contracts for less than 5%, and nonunion workers pick the remaining 25%.

“In effect, then, all those fellow lettuce boycotters at the Democratic convention were merely supporting an AFL-CIO union against the independent Teamsters. Maybe they got their orders from their new leader, Sen. George McGovern, who is trying to patch up relations with the AFL-CIO and has praised Chavez as ‘one of the greatest living Americans.’ Mr. McGovern has no such affection for the Teamster leaders, who are generally in Mr. Nixon’s camp.”

As we know from Mike’s first column this week, AFL-CIO president George Meany has no affection for George McGovern. Is the lettuce boycott thing really a way to win George Meany’s heart? Hm.

In any case, the Illinois delegation unanimously backed the Singer-Jackson delegates’ lettuce boycott resolution, and Clyde Choate made convention history.

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Mike already trimmed the verbal fat, so he doesn’t need to be summarized Reader’s Digest-style, either. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, plus the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. You can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many iconic columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there’s riveting work covered here you will never read elsewhere.

If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career which includes a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

Do you dig spending some time in 1972? If you came to MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY from social media, you may not know it’s part of the book being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

To get MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY in your mailbox weekly along with THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 and new chapters of the book—

SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE!