To access all website contents, click HERE.

This is the first of several collections of THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 posts on a single topic, posted initially for readers interested in a deep dive into the Illinois Central ahead of the tragic crash of October 30, 1972. We begin with a brief historical look at the IC.

For coverage of the accident itself, see TCD1972: Death Train. Post-crash coverage will continue in TCD1972 through the end of its first pass through the year, at which point I’ll include it all here.

The Illinois Central Railroad literally runs right through the beating downtown heart of Chicago—and the South Side.

At “Roseland, Chicago: 1972,” we care about the IC because the hero of the book at the center of this Substack, Steve Bertolucci, grew up riding the IC downtown from Roseland. As an adult, he takes the IC from Hyde Park to his office at Rose & Rose on the 13th floor of the IBM Building. By then, the IC had been absorbed into the larger Metra commuter train family, and its official name became “Metro Electric” because the other train lines used diesel engines. But old habits die hard, and Steve was no more likely to call the IC the “Metra Electric” than he was to call the Sears Tower anything but the Sears Tower, regardless of who owned or named it.

But there’s a lot more to the Illinois Central than the commuter line serving the South Side and south suburbs. It’s actually an integral part of Chicago history. Pull up a chair, if you have time. In this Chapter Note, we pull together the IC history footnote from Chapter 2, and all the THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 newspaper items concerning the train line. Here we go:

As a kid, Steve took the IC with his family to see Marshall Field’s Christmas windows, and he took the IC with his rebellious Nona in 1972 on a secret journey to see “The Godfather.” Steve’s mom said he was too young, but Nona wanted company, and she wasn’t waiting months until the blockbuster film finally moved on from the Chicago Theater and filtered out to smaller neighborhood theaters—for that is how movies worked in 1972.

Back then, the seats were wicker and destroyed all the women’s nylons. And the women were all wearing nylons in 1972. Soon, “nylons” or “stockings” would be referred to only as “pantyhose,” once a “panty” was added to the “hose” to create a single uncomfortable garment. Who knows what Future Readers may call them, if they still exist.

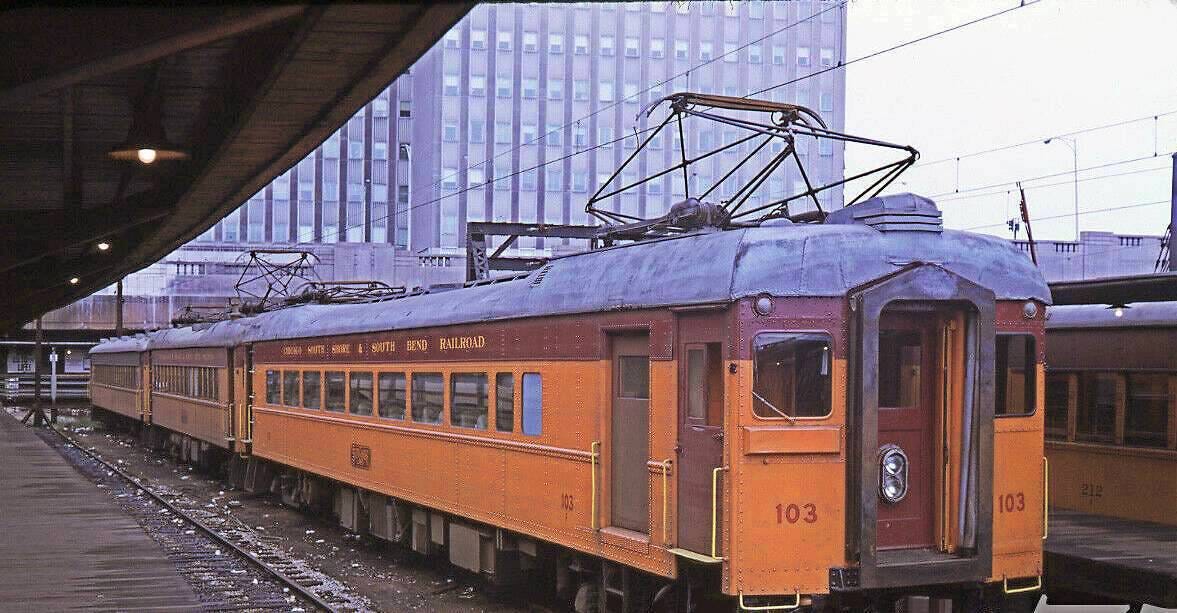

The single-story IC train cars were nearly 50 years old by mid 20th century, ancient and delapidated. In 1972, the IC was slowly adding the first shiny new double-decker orange-and-silver train cars of a fleet ordered from the manufacturer in 1969.

The IC’s main line runs on an embankment above the South Side neighborhoods it serves, always getting closer to the lake as it approaches downtown. Grown-up Steve gets on the IC at 53rd Street. The first good glimpse of the lake comes right here, but you have to look quickly as the train rumbles over the 53rd Street viaduct the lake disappears behind buildings again. After 47th, the buildings lining the track’s east side stop abruptly. Now the train runs just west of Lake Shore Drive all the way to 12th Street, where it reaches the southern end of Grant Park, often called “Chicago’s front yard.”

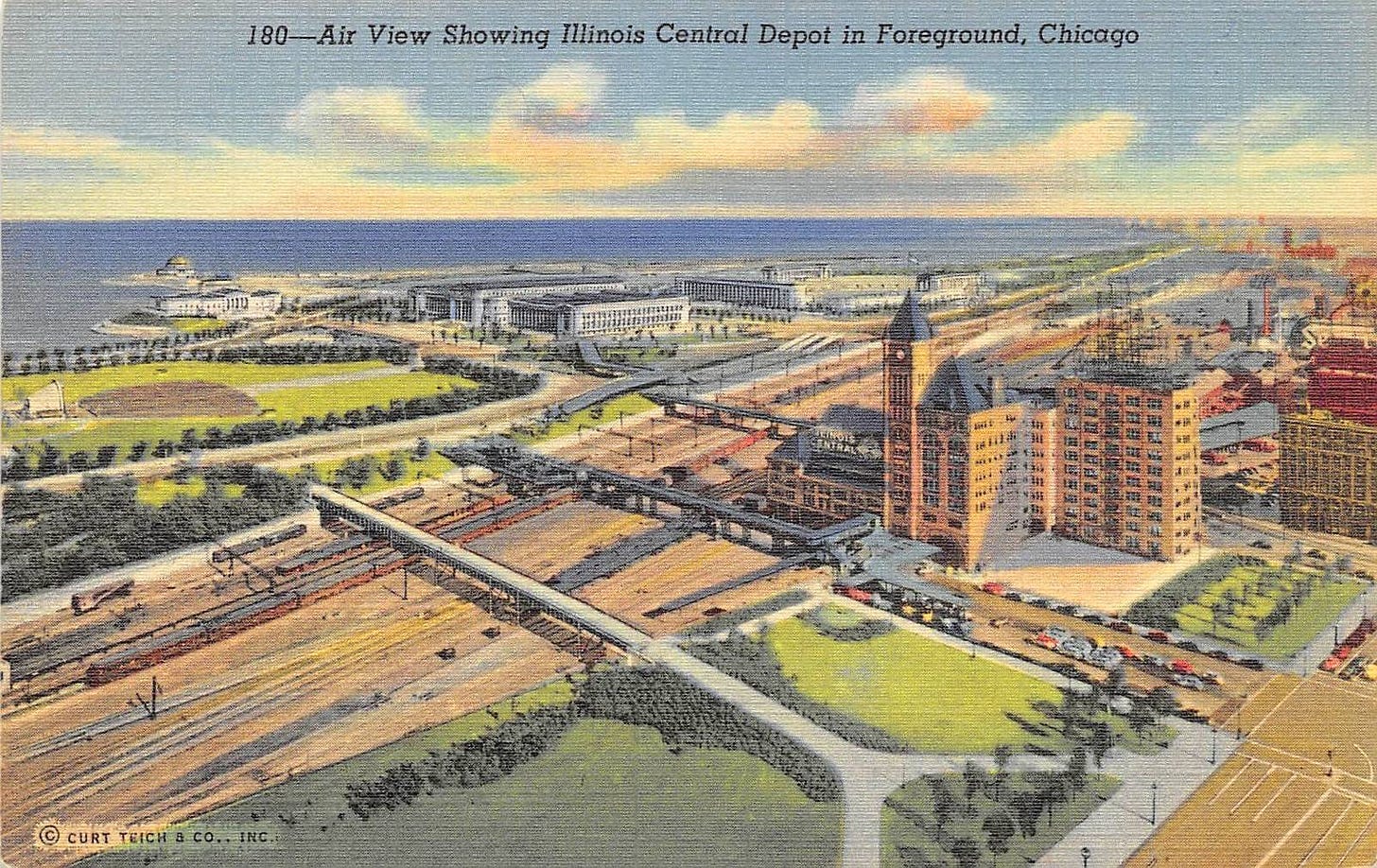

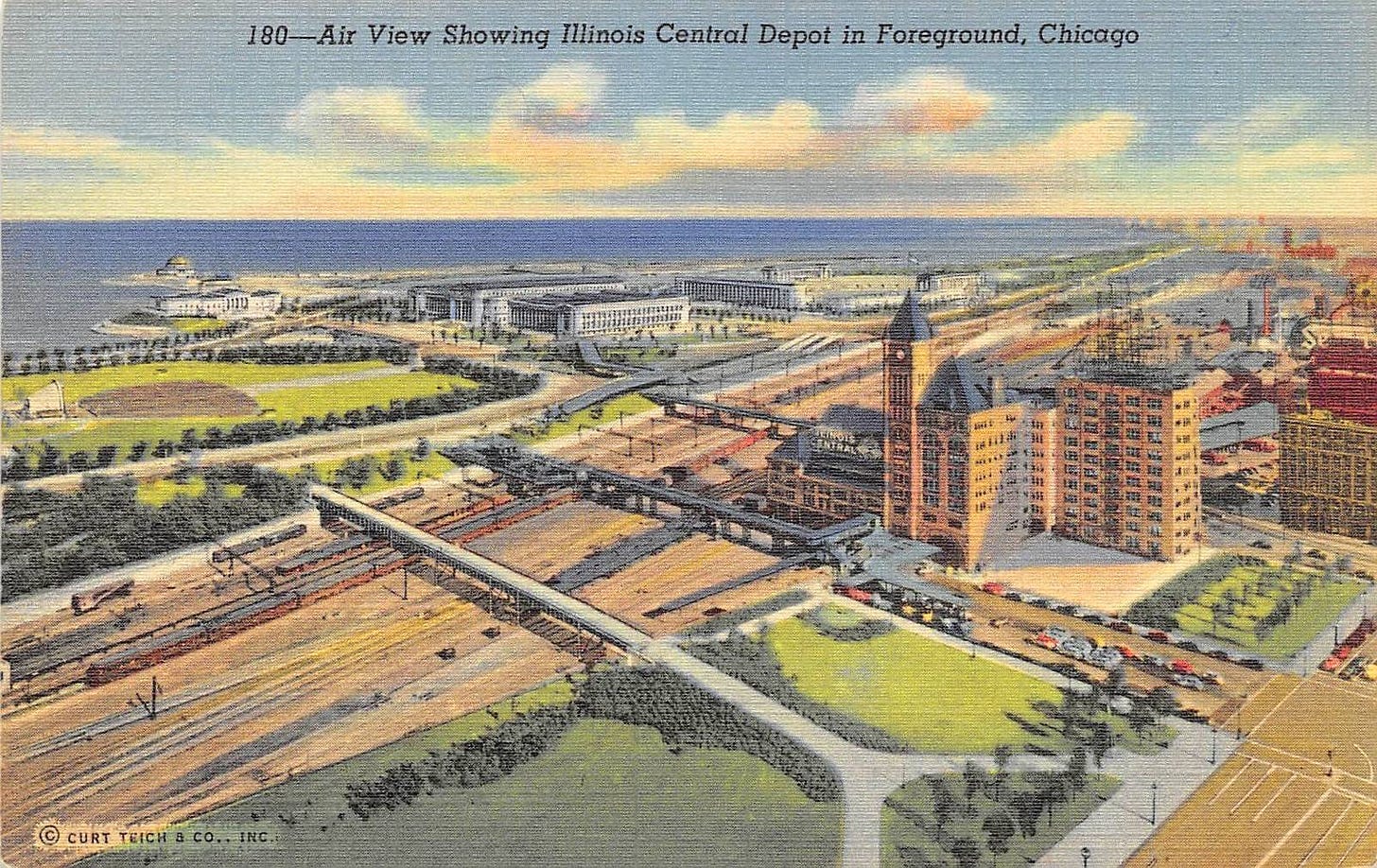

Here the IC tracks begin rushing through the city’s front yard like a river in a railroad canyon. The canyon is soon one level below grade, with stone walls built by men rather than cut by flowing water. Here’s a slightly newer view than the Mighty IC logo above, though this one is also before 1976, since the Art Institute’s 1976 addition isn’t there yet:

North of the Art Institute—after the foreground of the photo above ends—the tracks used to pass a giant parking lot to the east, then disappear entirely underground by the end of Grant Park at Randolph. Now the tracks disappear sooner, covered by Millennial Park.

Here’s another postcard from John Chuckman, looking west over the old vast parking lot. It’s like an asphalt Great Plains. You can see the Wrigley Building peeking in on the right side in the distance.

Steve gets off the IC at the end of the line, at the main station underground at Randolph and Michigan. It’s nothing special and never was. Steve and his fellow IC commuters herd themselves like intelligent cattle through the Randolph station’s corridors, so reminiscent of Stockyard chutes with the low ceilings and stuffy old air. Finally they swell up the stairs that deposit them next to the broad stone steps of the old library’s front entrance. Then Steve and his fellow travelers all blink in the sudden sun. Their first glimpse of the Loop always radiates from that southwest corner of Randolph and Michigan.

The IC commuter train line is now part of the regional Metra train system, so Steve is really arriving downtown at the Randolph Street Metra station, which isn’t even the Randolph station anymore. It was renamed for Millenium Park after Chicago spent hundreds of millions of dollars to turn the northwest corner of Grant Park into a tourist Disneyland at the turn of the 21st century.

To anyone who grew up taking the IC back in the day, it’s still the IC, and still the Randolph station—or just “Randolph.” People who call this train line “Metra” give away their relative newcomer status. People who call it “the IC” give away their old-timer status. Which status is preferential depends on your perspective. Neither should be preferential, but we all know everybody has a preference.

The Mighty IC: Even a train has to start somewhere

Most people remember, in a general way, that Chicago beat out other Midwestern cities like St. Louis to become the country’s central hub for transportation and, thus, trade. But that didn’t happen automatically just because Chicago sits on the shores of Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Chicago River.

As Donald L. Miller puts it in his epic book City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America, “Nature hadn’t created Chicago….she had merely made it possible. The city would not have been set on its course had not men of energy and empire first envisioned and then cut a canal”—the Illinois and Michigan Canal.

The I&M Canal opened in 1848, linking the south branch of the Chicago River to the Illinois River, running from Bridgeport to LaSalle-Peru. This 96-mile long, 60-foot wide artificial river, dug by Irish immigrants over the course of a dozen backbreaking years, connected Chicago by water for the first time with the Mississippi.

Suddenly, ships could travel from New York to the Gulf of Mexico—via the Erie Canal to the Great Lakes, on to Chicago, then through the I&M Canal to the Illinois River and finally the Mississippi to the Gulf.

That was Chicago’s first punch, a hefty left jab at all its Midwest rivals. The knock-out came chugging along railroad tracks.

“It was water, ironically, that guaranteed Chicago’s place as the nation’s railroad hub,” Miller explains. “With the completion of the Erie Canal and the Illinois and Michigan Canal, Chicago’s location as the terminus of an all-water route between New York and the Gulf of Mexico, the longest inland waterway in the world, made it virtually certain the city would become a major rail center.”

And it happened fast.

“By 1857, Chicago was the center of the largest railroad network in the world, consisting of three thousand miles of track,” writes Miller. “Almost a hundred trains entered and left the city every day, and everywhere its trains went, they changed frontier into hinterland and brought to the city the multiplying products of farms and forests.”

Chicago’s first railroad was the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad, starting operation in 1848. But, writes Miller, “The railroad that had the earliest and longest-lasting effect on Chicago’s physical environment was the formidable Illinois Central.”

Even back then, Chicago became Chicago through clout. In 1846, Illinois’ newly-minted U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas went to Washington determined to pass the necessary federal legislation for an Illinois Central Railroad, running the full length of the state and down to the Gulf of Mexico. Douglas succeeded—and after moving to Chicago in 1847, he amended the IC plan to include a branch to his new hometown. Then Douglas bought a lot of the land that now makes up the near South Side, which an IC Chicago branch would need. Douglas simultaneously made a nice profit selling the railroad the land it needed, and made his remaining holdings more valuable as part of the IC route.

You can still see Stephen Douglas from the IC as it passes 35th Street, on the west side of the tracks. Sort of. You’re looking at a ten-foot high statue of Douglas, dwarfed by its 40-foot marble column. This seems almost a purposeful irony, since the diminutive Douglas was known, of course, as “the little giant.”

The statue tops Douglas’s tomb, no longer set in quite so large and elaborate a park as in the postcard above. Douglas is a controversial historical figure, since he argued against Abraham Lincoln’s anti-slavery position in their famous 1858 debates, when Lincoln unsuccessfully challenged Douglas’s senate seat. If you haven’t read about Douglas since grade school, though, the details are fascinating, including Douglas’s final travels to rebellious states, attempting to stave off secession. Douglas’s death from typhoid in 1861 at 48 was at least partially attributable to those travels, which left him in sight of the IC.

“In 1856 the 705-mile-long railroad from Chicago to Cairo, the longest in the world, began regular service, and Chicago immediately felt its impact,” writes Miller. “Trade on the upper Mississippi that had previously gone downriver to St. Louis was rerouted by rail to Chicago, whose boosters began calling the Illinois Central ‘the St. Louis cutoff.’”

As we know, the mighty Illinois Central’s wide, raging river of railroad tracks still gouges a canyon through Grant Park, Chicago’s front yard.

But Senator Douglas didn’t own Grant Park, so how exactly did that part happen?

Back to Donald L. Miller, and the I&M Canal. In 1836, the lakefront strip of shoreline stretching south from the site of the old Fort Dearborn on the south bank of the Chicago River was part of the canal land carved up into lots and sold by the state of Illinois. The state acted through canal commissioners whose last names will be familiar to Chicagoans still in 2022: William F. Thornton, William B. Archer, and Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard. These three men, all on their own, decided not to sell the lakeshore. Instead, they drew up the first famous map labeling Chicago’s lakefront “Public Ground—A Common to Remain Forever Open, Clear, and Free of Any Buildings, or Other Obstruction Whatever.”

Fast forward two decades. Wealthy Chicagoans of the 1850s lived in fine houses lining South Michigan Avenue, overlooking a popular lakefront park. But Lake Michigan had eaten away at the park until storms sometimes drove the waves right across Michigan Avenue against Chicago society’s front steps. Nobody wanted to pay for building a seawall or other barriers to contain the lake. So in 1852, the city council “cut a deal with the Illinois Central, giving it a lakefront right-of-way to the terminal and freight complex it had just purchased on the old Fort Dearborn estate in exchange for construction of the badly needed dikes and breakwaters,” writes Miller.

The early IC ran into Chicago on that strip of lakefront land saved by Thornton, Archer and Hubbard, though it was now underwater. So the tracks originally sat on elevated train trestles several hundred feet offshore, with a parallel line of breakwaters protecting the tracks from Lake Michigan and simultaneously saving the inner shoreline. Here is an early map thanks to the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal:

And here is a photograph of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train bound for Chicago over the IC train trestle in 1865—also thanks to the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal. The train looks like it’s literally rolling across the water.

Chicagoans would fight the Illinois Central Railroad for the rest of the 19th century over the southern lakefront in Grant Park. It would take a nearly 20-year legal battle led by Chicago merchant Montgomery Ward to finally settle the question in favor of the public. That, and a lot of landfill through all the decades since, created the Grant Park you see today.

In 1972, the IC is in the process of merging with the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad. By the end of the year, the company will technically be the Illinois Central Gulf Railroad (ICG), but everybody will still call the company and its commuter train “the IC.”

The IC (railroad) will dump—er, sell—the IC (commuter line) to Metra in 1988, the company that runs Chicago’s other commuter trains. Then, as we noted earlier, the IC will become the “Metra Electric,” since it’s the only local commuter line that runs on overhead electrical lines rather than using diesel train engines.

Next, we hop on the IC in Steve’s 1972 world, as Chicagoans read about it in their five daily newspapers.

January 12, 1972

Chicago Daily News & Chicago Tribune

The Illinois Central Railroad’s commuter train had 18 serious delays in the last four months of 1971 alone, which brought the Illinois Commerce Commission sniffing around to see what’s up. ICC examiner Joseph McHugh came to Chicago to hold an investigatory hearing.

The Tribune’s David Gilbert reports that IC attorney Howard Koontz blamed the avalanche of delays on the IC’s new double decker train cars. The IC is slowly introducing the new double deckers, replacing their ancient single-story cars. The single-story cars have unraveling wicker seats that snag and destroy the women passengers’ nylon stockings. And they were all wearing nylons in 1972.

The double-decker cars are bigger and use more electricity, it turns out. Koontz asked the ICC “to order Commonwealth Edison Co, which supplies electricity to the I.C., to testify in a future hearing about the capability of Edison to meet increased electrical demands”.

But the Daily News’ Betty Washington reports further: IC power supervisor Everett E. Ellsworth testified that six of the 18 delays were caused by Edison’s substation near Flossmoor. “However, Ellsworth said there have been ‘other instances where power was available but because of some defect in the commuter cars or other facilities, power could not be used to operate the trains.”

In other words, 12 of the 18 delays can’t be blamed on Commonwealth Edison.

McHugh says he’ll have to investigate further to understand the true source of all the power failures. Adjourned until February.

“State Rep. Robert Mann (D-Chicago) and Rep. Bernard Epton (R-Chicago) testified that the delays continually inconvenience commuters.” For Older Readers: Yes, that Bernard Epton.

January 16, 1972

Chicago Tribune

no byline

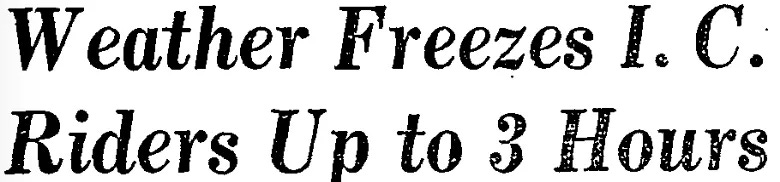

“The subzero temperatures turned the Illinois Central Railroad into a commuter’s nightmare yesterday,” the Trib reports. This is the drawback to an electric commuter train, versus a train pulled by a diesel engine.

“Some trains were delayed as much as three hours because of frozen switches, downed power lines, broken rails, and shorted signals.”

“We’ve had terrible problems,” IC spokesman Robert O’Brien told the Trib. “Crews are working throat the weekend in hopes of having a normal rush hour Monday….Our workmen are on the job around the clock, and some are so tired they have cried.”

January 22, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by David Gilbert

The Illinois Central Railroad announces it lost $1 million on its South Side/south suburban commuter line in 1971, and 5% of its riders too. That’s $6.75 million in 2022 money.

“Contrary to some folks’ belief that commuter operations are highly profitable, figures for the first 10 months of 1971 show a loss” per an IC spokesman. It’s the highest deficit since 1956, when the IC lost $1,141,000. There’s no information on whether that’s adjusted for inflation. If so, that would be $7.7 million in 2022 money.

The IC asked the Illinois Commerce Commission for a 7% fare increase increase last March, but the ICC hasn’t made a decision yet.

The IC spokesman also blamed losses on a 15% increase in costs, including labor and electricity, and the generally lousy U.S. economy.

And the IC is appealing the ICC’s order last fall to begin a 5-year program renovating or replacing 50 stations.

January 23, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by Fredric Soll

Fredric Soll—who I believe is the “Rick Soll” we see in other bylines—talks to commuters about the IC’s request for a 7% fare increase.

“Walter Hoeppner sat on the wicker-faced seat, letting the cold and the constant clickety-clack get the best of him,” writes Soll. “He was on the 5:47, on his way home to Flossmoor, a round-trip he makes five times a week.”

“Mad?” Hoeppner “rhetorically” asked Soll about the potential IC fare increase. “I’d be fuming. I’d hit the ceiling. Look at this.” Hoeppner waved his hand at the inside of the ancient IC car. “It’s cold, and and the trains are so often late. And already, I’m paying $29.90 a month for this service.” That’s $201/month in 2022 money. “I’d be mad as hell if they raised the fares.”

“Beside financial difficulties, the I.C. has been plagued by numerous breakdowns and, according to riders, delays of inexcusable length. On Jan. 8, some 8,500 commuters were delayed during the morning rush hour after an I.C. car motor assembly jammed in Hazel Crest Friday night. Several runs were an hour behind schedule.”

That little fiasco didn’t even make the papers.

Shore Shore and South Bend R.R. president James McCahey tells Soll that his company is asking the ICC for permission to decrease its service by nearly 50%—and that’s on top of crazy high prices that have Chicagoans in Hegewisch paying $44.60/month for service, compared to $31.80 for suburbanites in Matteson riding the IC. If you don’t know how far away Matteson is, check out the map above. It’s the last stop at the bottom of the map, while Hegewisch is at 130th Street.

“I know this train is awful,” one passenger tells Soll. “It’s too expensive for what you get, but I would not drive for anything. The I.C. management just doesn’t know how to run a business, and I ought to know.”

“The rider flashed an employment identification card and scurried off the train,” Soll concludes. “In large black letters across the top of the card, it said ‘Illinois Central Railroad.’”

February 7, 1972

Chicago Daily News

The West Pullman station was Steve’s station when the Bertoluccis used the IC, leaving from their bungalow at 12426 S. Wabash. That $400 would be $2700 in 2022 money.

February 7, 1972

Chicago Today: George Lazarus Op-Ed column

Chicago Today’s marketing columnist George Lazarus would reprise that role at the Chicago Tribune for decades after Today folded in 1974. This column appeared in Today’s op-ed section.

“Riding the Illinois Central can get any commuter steamed up,” Lazarus opens.

“That steam, incidentally, doesn’t come from those 1920 vintage cars of the south suburban commuter line. The cars are usually cold.

“What bothers me—and I’m sure thousands of other commuters—is the complete breakdown of service, equipment problems, and far-too-frequent delays.”

Lazarus’s normal trip downtown from Flossmoor should take about 40-45 minutes. Instead, it took 90 minutes recently when his train was blocked by a stalled train up ahead, and had to back up to switch to another track. His neighbor recently spent two hours going downtown on a Saturday.

“Some people suspect that the folks at the I.C. have purposely ordered a slowdown to justify the railroad’s proposed increase in fares, which has been under review since last March,” writes Lazarus. “The I.C. claims it lost more than $1 million last year.”

And Lazarus recently overheard this conversation on the train between two fellow passengers:

“‘In our company,’ said one, ‘two people being equal and competing for a job, our personnel manager won’t hire the one who rides the I.C.’

“‘Yep, you’re right,’ said her companion. ‘When I got my job, the boss wanted to know what I ride. I said the I.C. He answered: ‘You do have a problem.’”

February 7, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by Thomas Buck

The IC has a new reason for its declining ridership. An anonymous IC spokesman now says stations near the Dan Ryan and its CTA L service are down 40% in passengers.

It’s odd the IC didn’t mention this before, since the Dan Ryan L—known in 2022 as the Red Line—began service on Sept. 28, 1969, almost three years ago in our time line.

The Tribune’s Thomas Buck says the Rock Island, which serves customers west of the Ryan, has been harder hit according to a Tribune “survey,” but the IC claims its losses are just as bad.

“However, the I.C. spokesman explained that no determination has been made on how much of the loss was attributable to the Ryan competition and how much to other factors known to have reduced commuter riding on Chicago’s South Side.”

Reporter Buck is being diplomatic here for some reason. The other factors are the IC’s awful service and high prices, as reported on January 12, January 16, January 23, in the George Lazarus column immediately preceding this item, and lower down in this post on February 12.

The Rock Island says its 40% drop happened within three months of the Dan Ryan L service. The I.C. more vaguely says its 40% reduction happened since the Dan Ryan service began.

But then, at the very end of the article, Buck adds this from the IC spokesman:

“However, this area also has been one of changing neighborhoods. Part of our decline in commuter patronage at these nine stations undoubtedly also has been due to the change in the population of the area.”

February 12, 1972

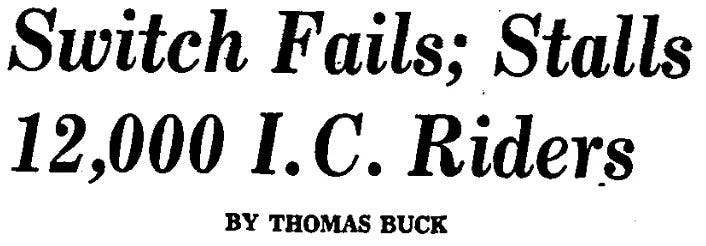

Chicago Tribune

Thirty IC trains were late during peak morning rush hour yesterday, which meant 12,000 passengers got to work late.

“With nerves on edge from this winter’s wave of delays on the Illinois Central, many of the frustrated commuters became even more irritated when they found themselves sitting on stalled trains almost within a stone’s throw of their downtown stations,” reports the Trib’s Thomas Buck.

The IC says a switching problem at 11th Place caused the 30-train back-up, lasting 5-23 minutes.

An IC spokesman said 30 trains were affected because of the crucial spot involved.

“The railroad spokesman likened the 11th Place point of the commuter system to an hour glass, with 11th place being a location where the track system narrows down and then spreads out again.”

But the Trib reports that an even worse delay happened Jan. 28, “when 75 trains were delayed for a variety reasons.”

The Trib doesn’t mention that the 75-train delay didn’t make the papers.

February 15, 1972

Chicago Daily News

February 17, 1972

Chicago Daily News

Last month, two spokesmen for the Illinois Central appeared at an Illinois Commerce Commission hearing looking into the IC’s dismal recent service record—18 serious delays in the last four months of 1971 alone.

At that hearing, one IC official blamed Commonwealth Edison for failing to supply enough power from its substations—but admitted that the IC’s new double-decker cars are bigger than the old ones, and use more electricity. The other IC official admitted that lack of electricity was only a problem in six of the 18 delays.

The ICC hearing officer adjourned until February for more investigating. At the February meeting, the hearing officer talks to Commonwealth Edison. Commonwealth Edison blames the IC.

February 17, 1972

Chicago Tribune

This time, the Tribune has more information than the Daily News:

The Commonwealth Edison representative says the 30 new double-decker IC cars introduced so draw more electricity when they’re started, causing circuit breakers to short. But Edison has modified the circuit breakers to handle the bigger surge, and they should be done installing new relay systems by the end of the month.

February 21, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by Thomas Buck

Nine of the top IC executives agreed to talk with Tribune transportation reporter Thomas Buck, apparently hoping to put a good spin on the IC’s current sorry state. Among other strange things about this story: None of the executives are identified by name, but Buck never calls them “anonymous.”

Recap: The Illinois Commerce Commission held two hearings in January and February into the IC’s recent record, after 18 reported serious delays in the last four months of 1971 alone. Part of the problem, the ICC learned, is that the IC’s new double-decker cars, slowly being added into service, use far more electricity than the old cars. The new double-deckers have been shorting Commonwealth Edison circuit breakers when they start.

The delays continue in 1972, including:

About 8,500 IC passengers were late to work on January 8 when trains were up to an hour behind, after a car motor assembly jammed in Hazel Crest.

Subzero temperatures on January 15 froze switches and broke power lines and rail ties, delaying trains up to three hours. An IC spokesman said workmen were working around the clock, “and some are so tired they have cried.”

On January 28, 75 trains were delayed “for a variety of reasons”—the worst delay so far.

On February 11, a switching problem at 11th Place during morning rush hour caused a 30-train back-up, making 12,000 passengers up to 23 minutes late for work.

The over 38,000 daily riders on the IC “are suffering thru the worst winter the railroad has experienced in its 116 years of providing commuter service for Chicago’s South Side and south suburban area,” Buck writes today. IC passengers are “plagued...by the almost daily irritation of stalled trains”.

But the men who run the IC “want the public to know that they are equally as irritated and frustrated.” They “admit that further delays and breakdowns in operations may well be in store…for some time to come.”

But the IC executives think this rocky period will be over by next winter, when 130 of the new double-decker, air conditioned cars will fully take over for their 46-year-old predecessors. Even though the new cars have caused delays by short-circuiting Commonwealth Edison breakers, the IC says the old cars have caused “most” of the problems due to frequent breakdowns—and because the old cars have no telephone or radio equipment to communicate with control centers during those breakdowns.

Finally, at the end of the article, reporter Buck discloses a “compounding” factor in the IC’s troubles— “a major decision made four years ago by the management of Illinois Central,” combined with “a delay in the delivery by the manufacturer of the new fleet of modern cars.”

That “major decision”? The IC managers, knowing they were about to get a batch of new train cars, “decided that no major overhaul work or other major repairs would be made to the old commuter cars. Instead of spending money to rebuild the old cars for 10 to 15 more years of operation, the Illinois Central officials specified that the cars be kept running on a safe basis at a minimum of maintenance expense.”

Reporter Buck charitably likens the IC to the owner of an old car “who realizes he cannot afford to buy a new auto for another year or two.”

The IC made the decision to skimp on repairing its old train cars after the Chicago South Suburban Mass Transit District was formed to qualify the company for federal funding to buy new ones. The federal government is paying 2/3 of the cost for the new double-deckers, while the IC pitches in $13 million.

Trib reporter Thomas Buck is too polite to conclude that the IC’s cheapskate move came back to bite the railroad in its big metal ass.

The closing quote, from a still-unnamed executive:

“We realize that it is a heck of a way to run a railroad, but the 500 men of the Illinois Central engaged in the commuter operations are doing the best they can under the circumstances.”

February 21, 1972

Chicago Tribune: editorial

Yesterday, the Trib ran a stunningly sympathetic story by transportation reporter Thomas Buck on the Illinois Central’s ridiculous mismanagement. The IC’s top managers admitted that after getting federal money to cover 2/3 of the cost of a new fleet of train cars, ordered in 1969, they decided to stop doing any major repairs on the old ones. And they said the major source of delays is the old cars breaking down—exacerbated by the fact that the old cars have no telephone or radio equipment to communicate breakdowns with the IC control centers.

Today, the Trib runs a stunningly sympathetic editorial. “In an unusual interview with TRIBUNE reporter Thomas Buck, officials of the line admitted that their service has been pretty poor these past few months,” writes the Trib editorial board.

The editorial ticks off the IC’s problems—sub-zero temperatures, dilapidated old cars, delivery of the new cars a few months late. Plus: “Another problem has been the line’s antiquated communications system. The only way train crews have been able to report trouble is to get off the train and use the public pay phones in the nearest station. Often there aren’t any phones, thanks to vandals and at least one angry commuter, who tried to phone in a complaint about the service and ended up ripping the phone off the wall.”

The editorial does not mention that the IC executive admitted they decided in 1969 to stop fully repairing the old cars. Instead, the Trib emphasizes that the IC officials promise service will improve as soon as all the new double-decker train cars are in service, some time this summer.

“In the meantime, the railroad asks its customers to hang on. No one can expect the commuters to be joyous, but this refreshing kind of candor is certainly preferable to the usual official attitude, in which everyone pretends that nothing is going wrong.”

February 22, 1972

Chicago Daily News

by Jay McMullen

The Greater North Michigan Avenue Association sent Mayor Daley a telegram asking him “to halt the planning for a $9 million Columbus Dr. bridge over the Chicago River.

He means this bridge.

And yes, there were telegrams in 1972—but people generally used them on purpose as an anachronism, to make the point that their message was REALLY important.

“The bridge…would link the Illinois Central air rights area with the Near North Side.”

The Columbus Drive bridge is already slated for completion in 1975, but association president Stanley Goodfriend asked Mayor Daley to delay awarding the contract for designing it “Until the association has a chance to examine a traffic study of the area made for the city by the consulting firm of Barton-Aschman Associates.”

Goodfriend says the city promised to let the association study the traffic situation before going ahead with the Columbus Drive bridge. He claims the bridge, combined with extending Columbus Drive to Ontario, “would clog the Near North Side with traffic and force the cancellation of plans to build several new buildings in the Ontario-Ohio area.”

Goodfriend scores a solid 50% for seeing the future. We all know he was right on #1, but manifestly wrong on #2.

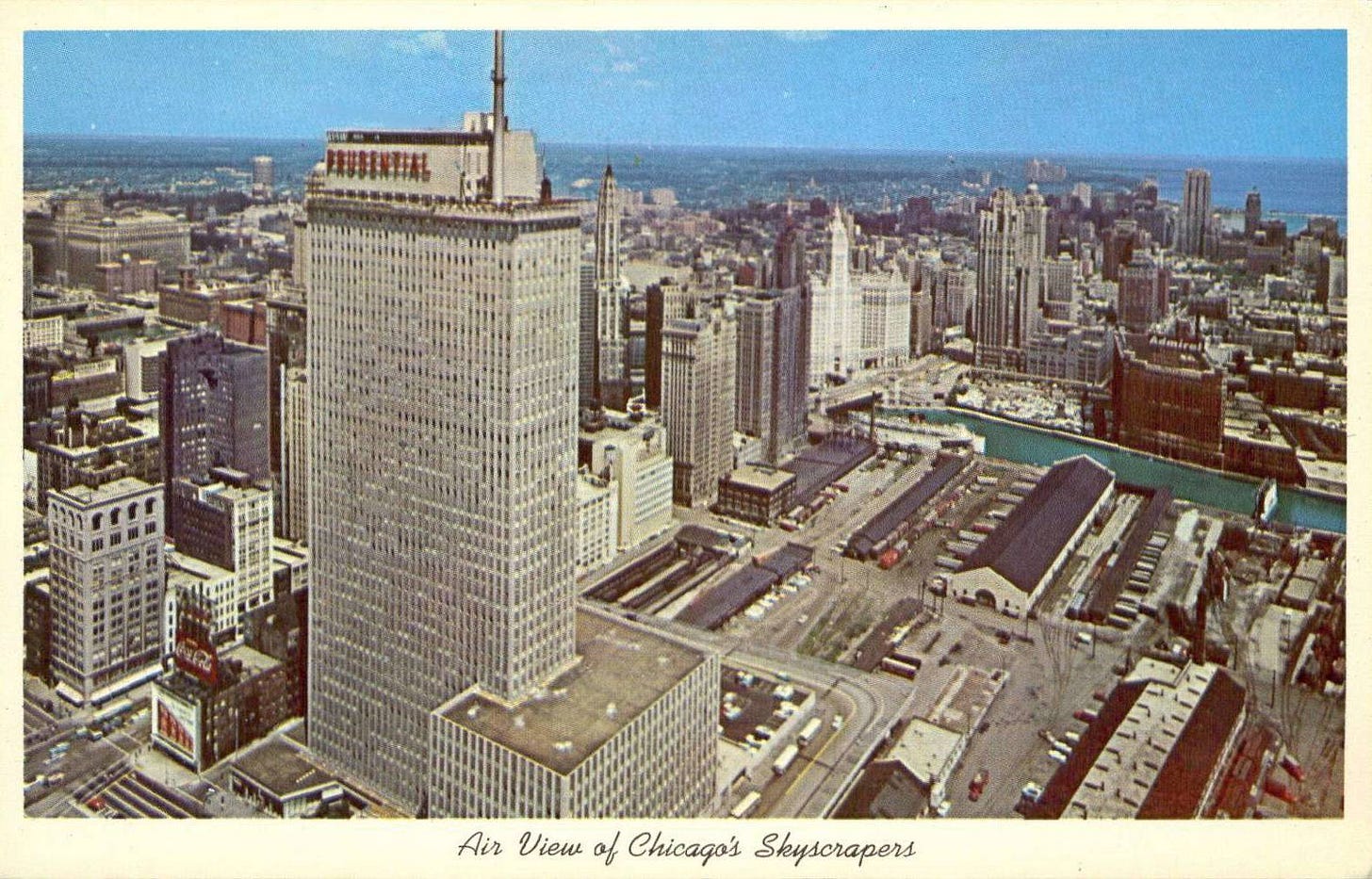

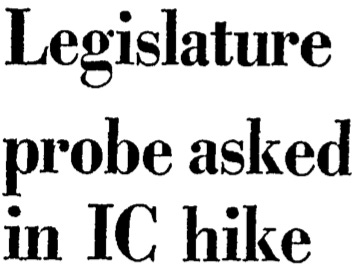

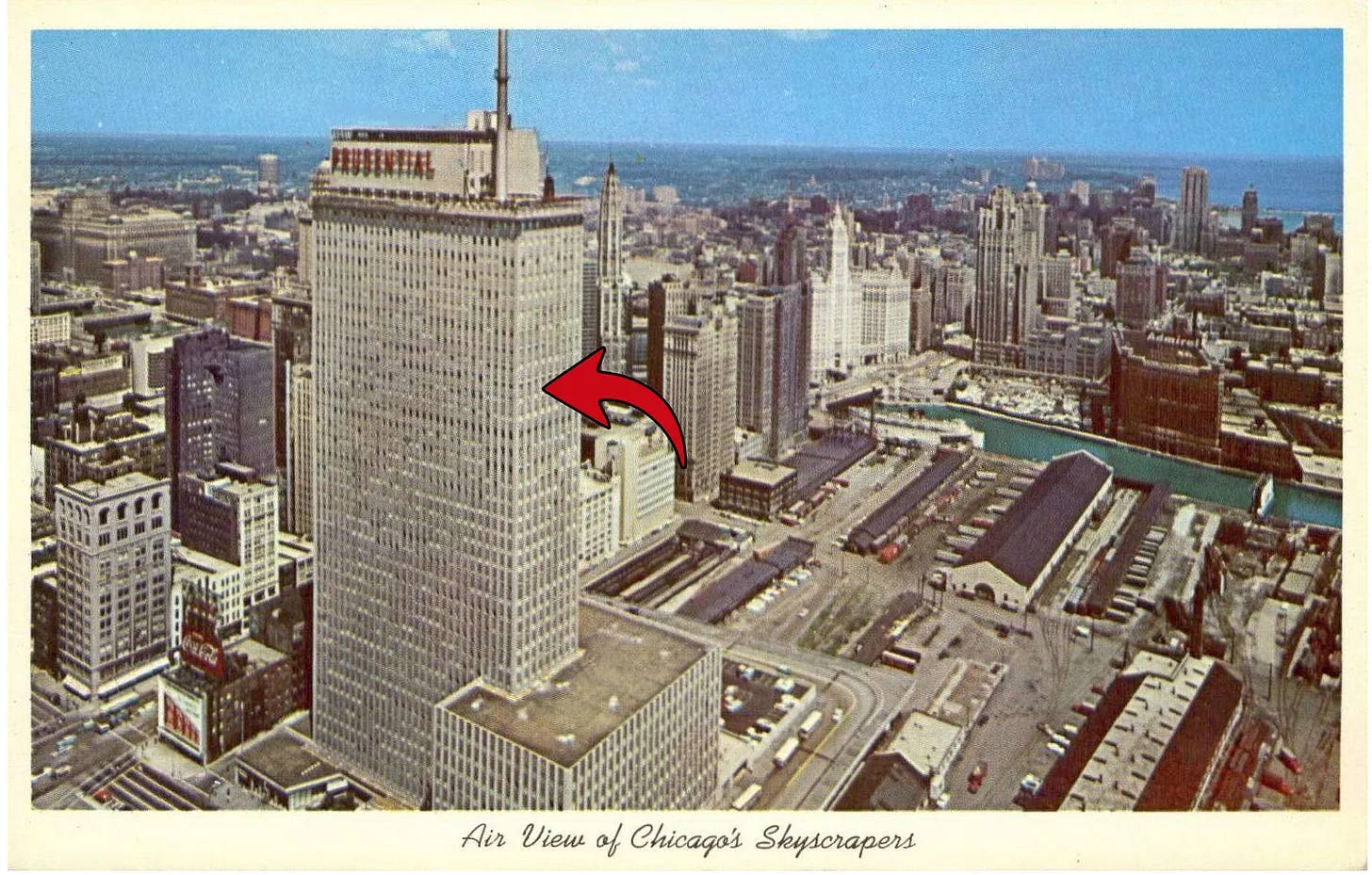

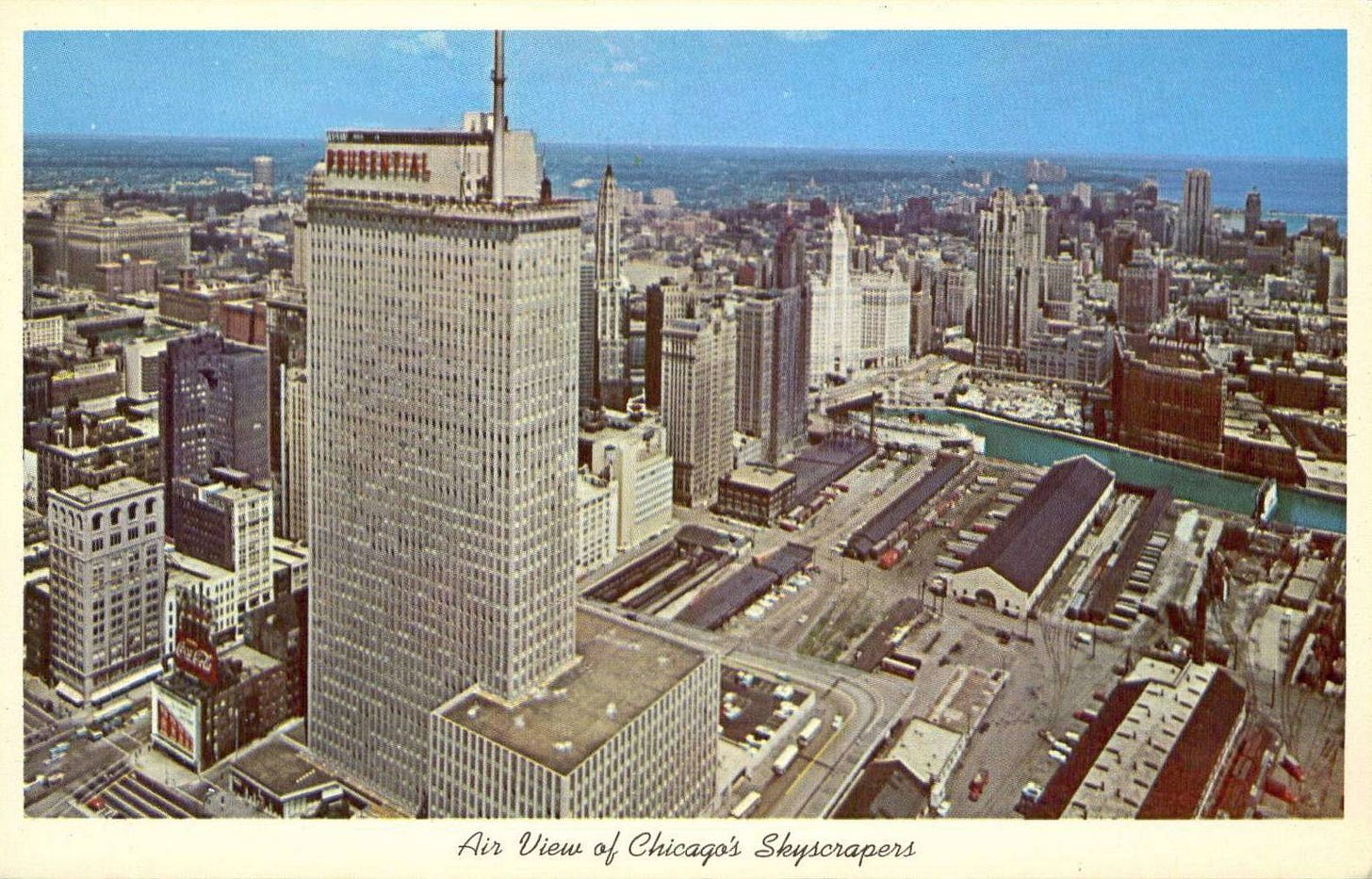

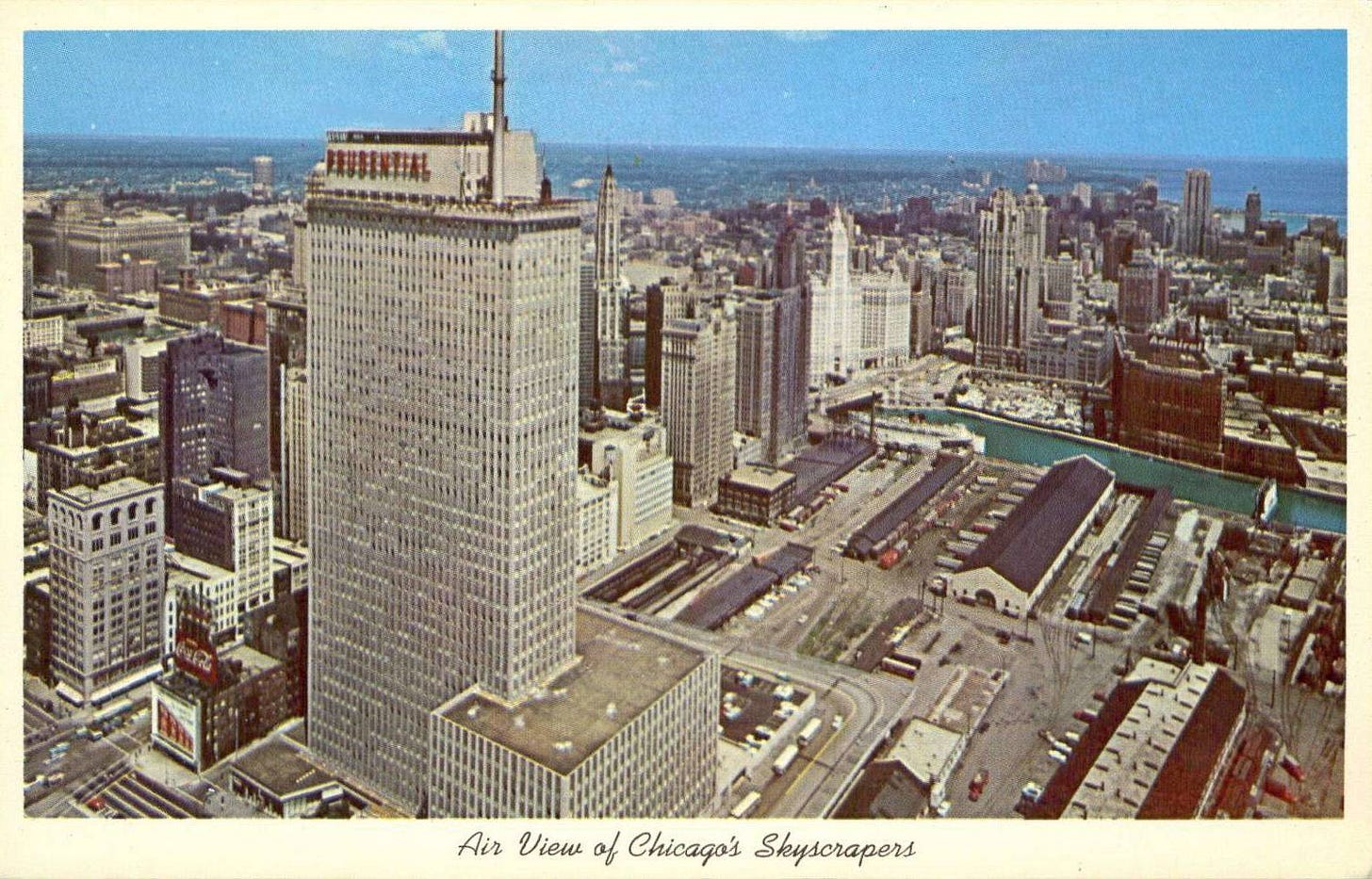

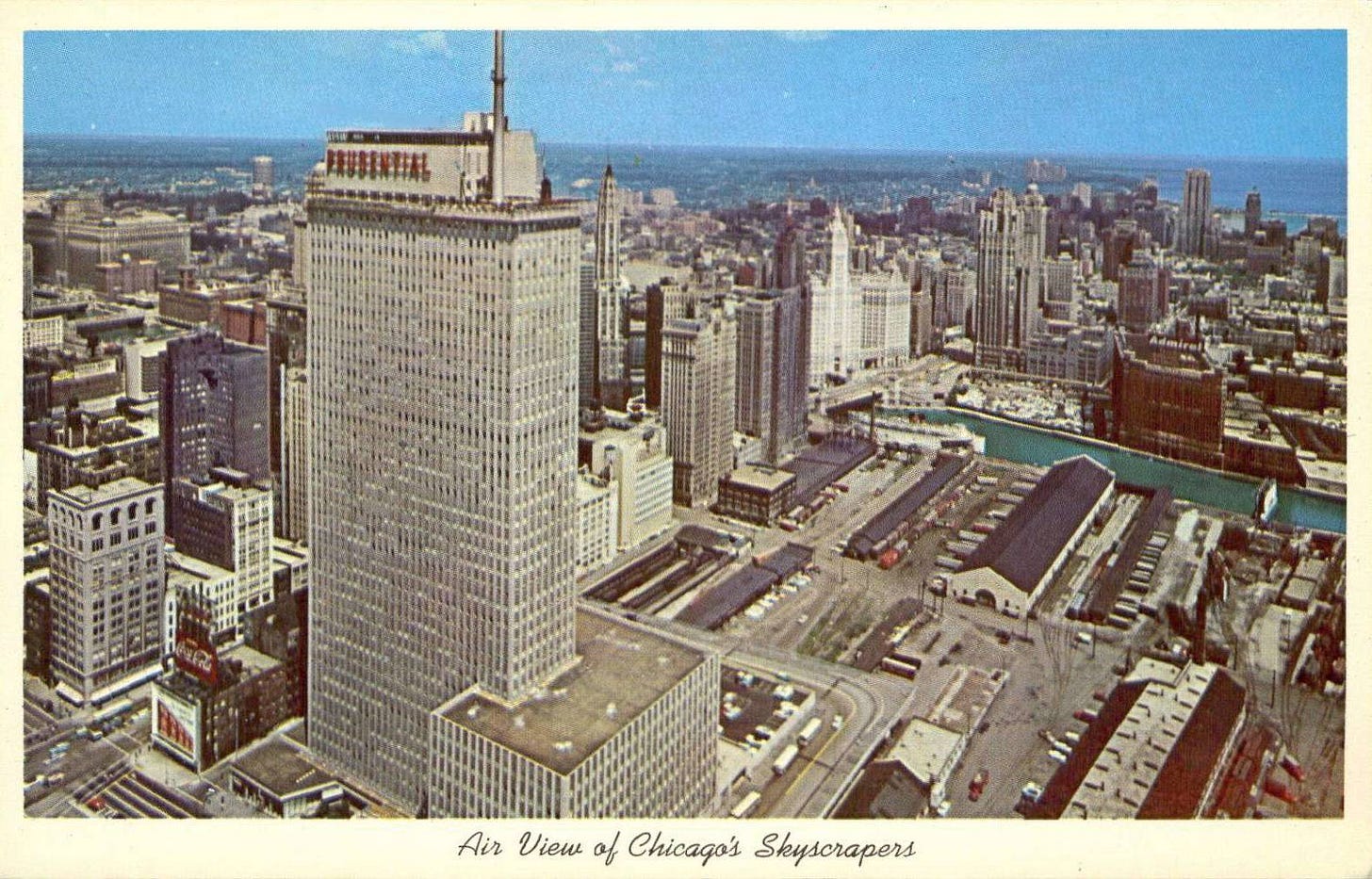

I suppose the Columbus Drive bridge can only make the Illinois Central Railroad land on the south bank of the river, the former site of Fort Dearborn, that much more valuable. Here’s what that vast area between the Prudential Building and the Chicago River looked like in 1960, before the IC started selling off the air rights—and before Columbus Drive extended across the river and into Streeterville.

February 25, 1972

Chicago Tribune

March 2, 1972

Chicago Tribune

Regular readers will recall that the Illinois Central commuter train serving the South Side and south suburbs has racked up a dismal record lately: Eighteen serious delays in the last four months of 1971, and at least five screw-ups so far in 1972, making tens of thousands of passengers up to an hour late for work.

Nine unnamed IC executives talked to Tribune reporter Thomas Buck last month and blamed the service outages and delays on their fleet of nearly 50-year-old train cars. But the executives also admitted they decided four years ago to stop fully maintaining those old cars, because they’re waiting on delivery of new double-decker cars. The IC executives asked customers to be patient, because all the new double-deckers will be in service by this summer.

Well, now it’ll be December 1.

Frank E. Rizzuto, director of commuter operations and services, told an Illinois Commerce Commission that the fleet of 130 new double-deckers will all be working by December 1.

Rizzuto also said 44 new double-deckers are operating already, and the IC is receiving deliveries of two new cars each week from the manufacturer.

“The I.C. asked the commission to rescind its order that the railroad rehabilitate and modernize 40 old commuter cars at a cost of $2.2 million to be used during rush hours.”

ICC hearing examiner Joseph McHugh “Indicated the order might be rescinded” in June, if the IC is able to get more federal and state money to buy an additional 15 new double-decker cars.

March 6, 1972

Chicago Daily News

by Terry Shaffer

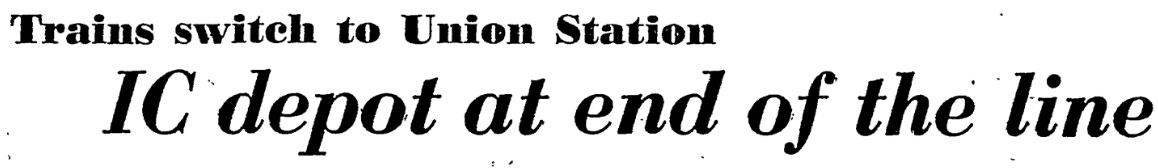

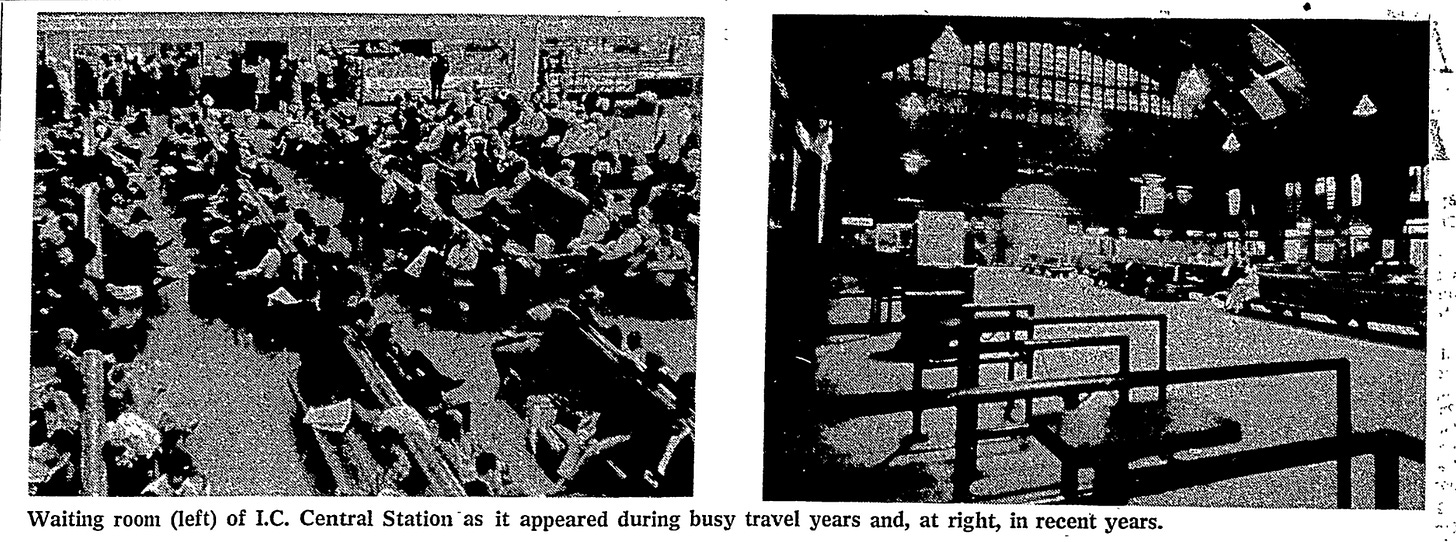

“The end of an era—an 80-year history filled with the bustle of thousands of travelers—came quietly Sunday for Illinois Central R.R.’s Central Station at Michigan and Roosevelt,” writes the News’ Terry Shaffer.

“The station, whose archaic clock tower served for years as landmark at the south end of Grant Park, lost its last three interstate trains to Union Station under new Amtrak plans to consolidate passenger services.

“The huge terminal building that houses IC’s home offices, was left astride the tracks with one foot in the past and the other in the future.”

Central Station, built for the 1893 Columbian Exposition, will remain standing for now as offices for the railroad. But it is doomed, writes Shaffer. Last May, Amtrak’s predecessor, Railpax, took over most railroads on a national basis. Then, the new Amtrak shifted all its trains to Union Station.

“And now, with the thirst of high-rise developers for valuable lakefront building sites, there is little room for sentimental attachment to a rust-red antique building with a clock tower.”

The IC commuter train is unaffected, since the 12th Street IC station is separate from Central Station.

March 6, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by Stephen Crews

The Trib’s Stephen Crews profiles the historic last two people to miss a train at Central Station, University of Illinois-Champaign students Ron and Chuck Schutz.

“You could almost hear the 79-year-old station snicker as, luggage-bent and puffing, they became the last ones to miss a train from the red brick edifice,” writes Crews.

“Ron, 21, and Chuck, 19, of 6701 S. Bennett Av., stood miserably in the nearly deserted waiting room and watched as the 6:30 p.m. Champaign Special pulled out with nary a toot.

“‘I’ve ridden this thing when it was 30 minutes late, and I’ve seen it two hours behind schedule, but this is the first time I’ve ever seen the darn thing leave on time,’ said Ron, a first-year medical student at the University of Illinois.

“….If we’re lucky enough to catch a bus, we’ll probably make it to campus by 3:30 a.m.,’ [Chuck] said with a sigh.”

March 26, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by Kenneth Ross

I’d love to know what’s up with the strange Tribune coverage of the IC. It’s like they have one editor who’s married to the IC president’s daughter, and when it’s his shift, the IC can do no wrong.

The commuter train has racked up a pathetic record lately. Besides 18 serious delays in the last four months of 1971, here are just two headlines from the five major mishaps reported so far in 1972:

The IC is so bad, Chicago Today marketing columnist George Lazarus wrote an op-ed column voicing a common suspicion—that the IC is purposely doing a lousy job to get the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC) to approve a requested 7% rate hike.

The Tribune is definitely covering IC problems. In fact, the Tribune covers more IC delays than the Daily News. Chicago Today is owned by the Trib, and ran the blistering Lazarus column. So we can’t say the Tribune is letting the IC completely off the hook.

But when Tribune reporter Thomas Buck interviewed nine IC executives last month, he covered the IC debacle like a paid spin doctor. Buck let the executives remain anonymous, without even mentioning it. And he left the most damning admission for the end of the lengthy article:

The executives blamed the constant IC breakdowns on their fleet of nearly 50-year-old cars, which are slowly being replaced with new double-decker cars. Then the executives admitted that when the new cars were ordered four years ago, they purposely stopped making thorough repairs on the old cars.

Reporter Buck merely compared the IC executives to anybody with an old car who “who realizes he cannot afford to buy a new auto for another year or two.” The next day, the Tribune ran a sympathetic editorial clapping the IC executives on the back for admitting their railroad sucked.

Which brings us to today’s strange, incredibly long interview with I.C. president Alan S. Boyd. Boyd “contends that thruout the accumulation of the industry’s poor image, ‘we haven’t spent enough time talking about what we’re doing to help ourselves.’”

“Boyd, who came to the Illinois Central as president nearly three years ago after serving as the country’s first secretary of transportation, reflected on a number of topics concerning the industry in a recent interview.”

It’s a bizarre mish-mash of sometimes unrelated bullet points like this one:

“There are some rays of sunshine peeping over the horizon as far as the railroad industry is concerned, even tho they might get lost in the clouds.”

Let’s just leave it there.

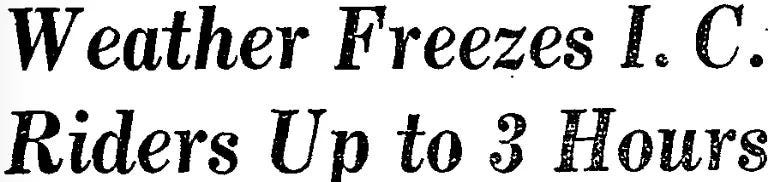

March 31, 1972

The constant IC train delays and breakdowns—like a 30-train back-up during morning rush hour earlier this year that made about 12,000 passengers late for work—have not made front pages. But this fare increase is above the masthead headline material for the Daily News.

“The Illinois Central R.R. was granted a 7-per cent increase in commuter fares Thursday, but the Illinois Commerce Commission also ordered it to make immediate improvements in its equipment, maintenance, signal system and stations,” writes the Daily News in a brief but front-page article.

An ICC spokesman cited the IC’s reported $1 million dollar loss last year as a prime reason to allow the rate increase, which can go into effect within five days after the I.C. files its new fare schedules with the I.C.C.

“An IC spokesman said the new fare will be filed with the commission immediately.”

Notably: “The commission directed the IC to continue to keep its 40-year-old cars in top shape until new cars, now on order, are received.”

That just has to be a response to a Tribune interview last month with nine top IC executives. The IC executives blamed the current avalanche of IC train breakdowns and delays on the old train cars, but also admitted that they decided four years ago “that no major overhaul work or other major repairs would be made to the old commuter cars. Instead of spending money to rebuild the old cars for 10 to 15 more years of operation, the Illinois Central officials specified that the cars be kept running on a safe basis at a minimum of maintenance expense.”

Chicago Today: New ICC hearing scheduled

by Robert Glass

The South Shore Chamber of Commerce plans to challenge the IC’s approved fare increase in court. Plus, Today’s Robert Glass reports that the ICC scheduled “a hearing into the railroad’s financial relationship with its parent company, Illinois Central Industries” on May 9.

“The hearing, part of an investigation begun by the commission nearly a year ago, will stress financial transactions between the two companies, the railroad’s expenditures for service improvement and the sale of part of the railroad’s assets by the parent company.”

It’s left unsaid, but that probably means the IC’s sale of air rights in two key downtown lakefront locations to high-rise developers. That is:

The old Fort Dearborn site on the south bank of the Chicago River, which 2022 Chicagoans will know simply as most of the high-rises now crowded between Randolph and Wacker, east of Michigan Avenue.

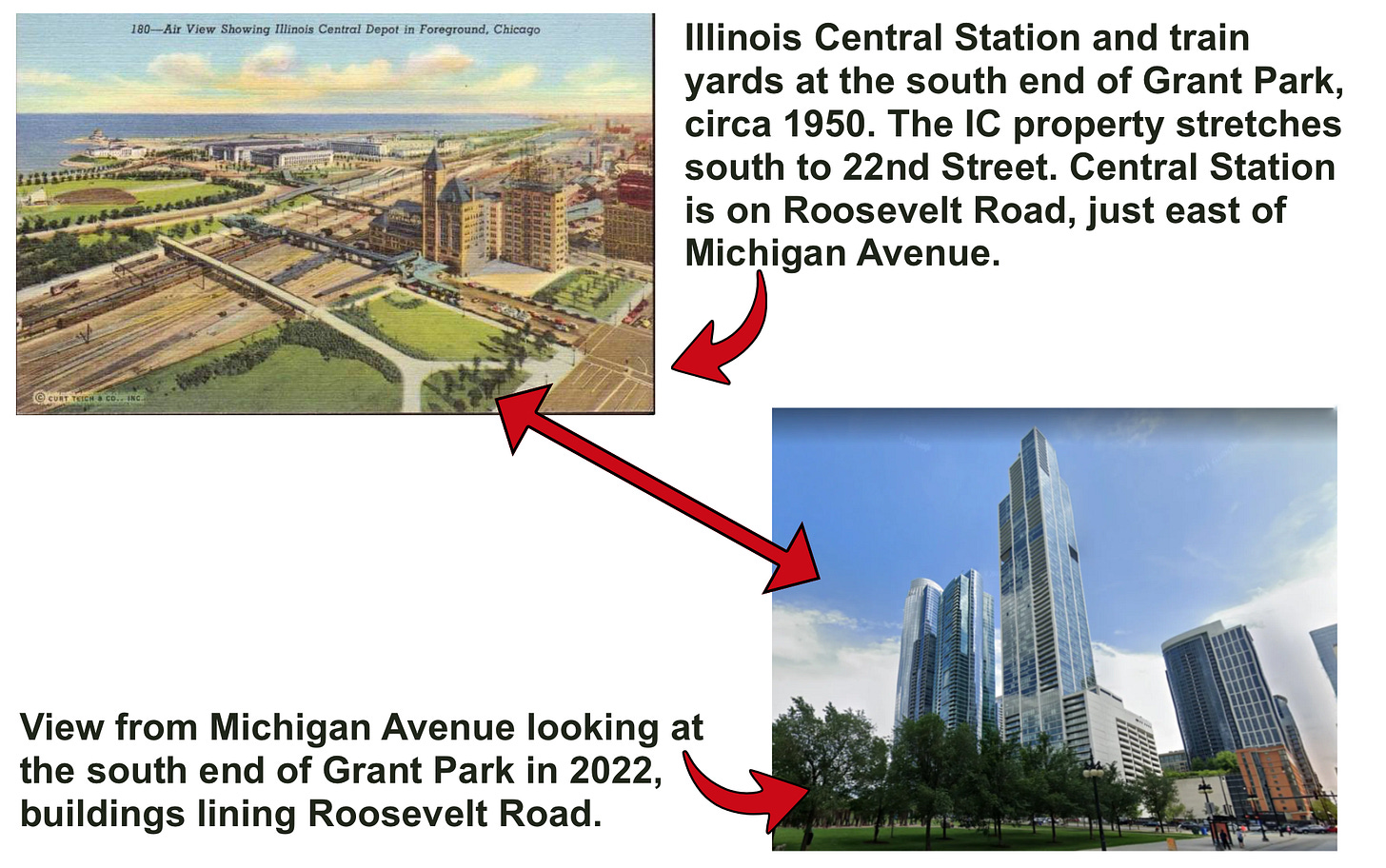

The vast IC rail yards on the south end of Grant Park, currently fronted on 12th Street/Roosevelt Road by the old Illinois Central Station depot pictured below. Chicagoans in 2022 have probably lost track of the high-rises that have since sprouted up there, along with the Central Station townhouse development. And that, incidentally, is why it’s called “Central Station.”

Do you dig 1972 news? Get more here.

April 6, 1972

Chicago Daily News & Tribune: Rep. Scariano on the IC rate increase

Last week, the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC) approved the Illinois Central’s (IC) requested 7% rate increase, and also scheduled a May 9 hearing to investigate the IC’s financial relationship with its parent company, Illinois Central Industries.

As Today’s Robert Glass reported, “The hearing…will stress financial transactions between the two companies, the railroad’s expenditures for service improvement and the sale of part of the railroad’s assets by the parent company.”

But State Rep. Anthony Scariano is calling for an investigation of the ICC’s “cozy relationship” with the IC, and the rate hike approval.

Per the Daily News, Scariano called the fare increase approval “tantamount to the regulated becoming the regulators.” He wants to “try to find out why the profit from the sale of expensive downtown property, including air rights, by the IC are not applied to the railroad’s commuter operations.”

The Trib gives the direct quote: “I am sick and tired of having the Illinois Central get permission to sell valuable tracts of property, including air space rights which are no longer needed for its carrier operations, only to have the proceeds of the sales credited to other than commuter operations.”

Scariano is talking about two downtown areas. First, the IC rail yard on the old Fort Dearborn site on the south bank of the Chicago River, seen below before the IC started selling the air rights…

…and more recently, below. I’ve added an arrow pointing at the original Prudential Building to steady yourself, since the difference is potentially disorienting.

Second, Scariano is talking about the vast IC rail yards extending south beyond Grant Park. The postcard below shows the Illinois Central Station depot circa 1950, just east of Michigan Avenue on 12 Street/Roosevelt—about where Indiana Avenue is today. The IC owns all the land between Michigan Avenue and the eastern edge of its rail yard, and extending south quite a ways—perhaps all the way to 22nd Street?

A more recent view across the south end of Grant Park from Michigan Avenue, thanks to Google Streetview:

April 5-6, 1972

Chicago Daily News & Tribune

Mayor Daley’s City Council voted 30-8 to set up procedures to let the city issue general obligation bonds without voter approval until all outstanding bonds equal 3 % of Chicago real estate assessed valuation, about $350 million.

You can guess who voted the 8 “nays,” but includes legendary 5th Ward Ald. Leon Depre, William Cousins (8th), Anna Langford (16th), Seymour Simon (40th), Bill Singer (43rd), Dick Simpson (44th), and lone Council Republican John Hoellen (47th).

“Dissenters contended the measure was a booby-trap, and said it opens the way for big tax increases,” write the Trib’s Edward Schrieber. “Administration aldermen countered that it was just a procedural measure to clear the way for what was authorized by voters when they adopted the new Illinois Constitution.”

But an even bigger debate raged over development of the IC’s property on the old Fort Dearborn site, which in 1972 still looks pretty much like this postcard, with the notable addition of the almost-completed Standard Oil Building.

Mayor Daley’s allies passed five ordinances to “appropriate money for widening and improving streets around the Illinois Central R.R. property east of Michigan Av.”

That includes $1,020,000 for the triple decking of Randolph Street from Michigan Avenue to Lake Shore Drive, $970,000 for extension of Wacker Drive to Lake Shore Drive, and $250,000 for extension of Columbus Drive from Monroe Street to the river,” writes the Trib’s Schrieber.

“Involved are 33 tall buildings under construction or contemplated in the area bounded by the river, Randolph Street, Michigan Avenue, and Lake Shore Drive.”

About $2 million will come out of the city’s take from state motor fuel taxes, per the Trib. That’s nearly $14 million in 2022 money, which still seems light for the planned streets, though state money is also promised to help pay for Wacker Drive.

The Council’s embattled independent faction again fought the good fight.

Ald. Seymour Simon pointed out that the new street infrastructure would allow high-rises on the IC land. “This is not going to make Chicago great, but grotesque,” said Simon.

“Independent Ald. Leon Despres (5th) said the ordinances cleared the way for ‘perhaps the biggest steal in all of Chicago’s history,’” writes McMullen, quoting Despres:

“All of the members of the City Council and the city planner are not going to be remembered for what they did, but for what they gave away, what they spoiled, what they ruined and what they embezzled,” said Despres.

Actually, in 2022 Chicagoans simply accept that you should not be able to see the lake from any point on Michigan Avenue between Randolph and Wacker. Most people traversing the area probably don’t even realize they’re walking on the top layer of three levels of streets.

Mayor Daley’s floor leader and Finance Committee chairman, Ald. Tom Keane, often considered the second most powerful politician in Chicago, says if the area isn’t developed, Chicago will lose jobs to the suburbs, out of reach of Chicago’s Black community—per the Daily News.

Per the Trib, Keane says corporations are moving their headquarters to Chicago from New York because of this kind of development. New York is a “dead stagnant city,” says Keane, while Chicago is the “city of the future.”

April 13, 1972

Chicago Tribune

no byline

Citizens for a Better Environment charges that Illinois Central president Alan Boyd is guilty of a conflict of interest as he heads Chicago’s Mass Transit Board, “which is responsible for building a subway to McCormick Place.”

Leave aside that the Mass Transit Board never got that done.

Mayor Daley appointed Boyd to the board in 1970. “The citizens group has charged the proposed subway will serve two lakefront developments planned on I.C. property. The developments are McCormick City, a real estate complex planned for I.C. air rights at McCormick Place, and the 83-acre Illinois Center Plaza just south of the Chicago River.”

As we’ve detailed elsewhere, the two IC properties are:

and:

“‘As chairman of the Mass Transit District and president of the I.C., Boyd is in a position not only to block off our lakefront but to use our tax money to do it,’ Duane Lindstrom, group spokesman, said yesterday. Lindstrom said without the new subway the developments planned on I.C. property would wither. ‘Boyd should resign his position,’ he said.”

April 20, 1972

Chicago Tribune

no byline

“Illinois Central Railroad officials said yesterday they expect to have all 49 commuter stations fully automated within two years.”

Here I will resist adding a laugh-cry emoji.

“The facilities would be complete with automatic ticket machines and close circuit television. The television, the officials said, would enable passengers to receive instant assistance if they ran into trouble with machine.”

Now resisting the urge to add the red-faced emoji with the line of symbols representing profanity across its mouth.

April 25, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Daley hails 36-story hotel near lake

by Robert J. Herguth

Mayor Daley ceremoniously breaks ground for the $40 million, 36-story Hyatt Regency Chicago, “apparently…the first big downtown convention hotel built here since the 1920s,” writes Robert Herguth.

Herguth has to explain where this is happening, because in 1972 almost the entire area between Randolph and the Chicago River east of Michigan Avenue is a vast rail yard for the Illinois Central—basically this postcard below, with the addition of the almost-finished Standard Oil Building just to the right of the Prudential Building.

The hotel is being “built on air rights south of the Chicago River on an extended Wacker Drive, two skyscrapers east of Michigan Av.,” he writes. That would be the Illinois Central Railroad’s air rights.

Mayor Daley, who is pushing for an airport in the lake eight miles off 55th St. and who opposes Illinois Rep. Robert Mann’s proposed Lake Michigan Bill of Rights, takes the opportunity to pose as an environmentalist.

“Our plan for the future is to open up the lake” for the people, he tells reporters. “No one has defaced our lakefront” since Daniel Burnham’s Plan of Chicago, he insists.

“‘Why shouldn’t people live in the center of our cities?’ asked Daley. ‘Why should they travel an hour on expressways…with all the tension’ such driving involves.”

Again, this is a groundbreaking for a hotel. Not a subdivision. But as we learned earlier this month when the City Council approved spending $2 million to create a three-level extensions of Randolph and Wacker from Michigan Avenue to Lake Shore Drive plus Columbus Drive from Monroe to the river, there are plans afoot to build up to 33 high-rises. Those plans are bitterly opposed by independent aldermen, state Rep. Anthony Scariano and Robert Mann, and community groups like Citizens for a Better Environment…and vigorously championed by Mayor Daley and his allies.

See Mike Royko’s April 26 column for more on Mayor Daley and lakefront development. As Mike observes of Mayor Daley’s lakefront preservation so far, “The Normandy invasion left fewer scars on the coast of France.”

Mike also notes Mayor Daley’s declaration that his plan is to “open up the lake” for the people.

“I’m sure he means it—but which people?” writes Mike. “Does he mean the Illinois Central Railroad people, who have been selling off land to high-rise people?”

Back to the groundbreaking:

“Daley and other dignitaries broke ground by shoveling dirt from a bucket lifted 30 feet in the air via crane to the level of the outside balcony of the 111 E. Wacker Building. Then they scattered the dirt back to the ground below.”

Guest appearance from “Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today”:

April 26, 1972

It’s your lake so back off!

“Mayor Daley, like any good comedian, delivers his best lines with a straight face.

“And he was getting them off to perfection yesterday as he took part in a ground-breaking ceremony for Hyatt Regency Chicago Hotel, on Wacker Dr. east of Michigan Av.”

As you’ll see, Mayor Daley’s groundbreaking speech turns into a peon to his devotion to an open lakefront for the people. Why? Background before we get to Mike’s column:

Illinois Rep. Robert Mann (D-Chicago) is trying to pass a Lake Michigan Bill of Rights in the state legislature. He got it approved by the House somehow, despite Mayor Daley’s opposition.

Mann’s bill would put the kibosh on Mayor Daley’s dream project, an airport in the lake eight miles off 55th Street. Imagine the contracts just for building the bridge connecting that monster to—what? Promontory Point? Fifty-seventh Street beach? Or maybe it would land in Jackson Park, the off ramp arcing over the Museum of Science and Industry?

As covered in THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, Rep. Mann appeared at an April 14 meeting of the Chicago City Council’s Environmental Control Committee, focused on the future of the lakefront.

“Let’s be candid about it—the next 10 years will be crucial to the life of Lake Michigan,” Mann told the aldermen. “Not only is the process of eutrophication or aging accelerating rapidly due to overdoses of pollutants, but also the lake continues to serve as a sink for toxic substances.”

But Mayor Daley’s commissioner for development and planning, Lewis Hill, appeared too—and he said the Daley administration opposes Mann’s Lake Michigan Bill of Rights because it “abrogates and dilutes the ability of the city to continue to preserve the lake.”

Instead, wrote Ray McCarthy in Chicago Today, “Hill presented an eight-point program which contained sweeping guidelines for conservation of the lake as a natural resource”.

The Daily News’ Jay McMullen (future husband of future Mayor Jane Byrne) noted that the most important points of Daley’s lakefront plan, presented by Hill, are that the “lake and shoreline area” can only be used for public purposes, and even then, nothing can be constructed if it will diminish water quality or cause ecological damage.

The issue is going to be what “lake and shoreline area” means. Hill never defined either term.

“Ald. Leon M. Despres (5th)” —legendary Ald. Despres, perhaps the thorniest of independent Democratic thorns in Mayor Daley’s side— “in a statement following Hill’s testimony, charged that the principles ‘are an attack on the lake,’” wrote McMullen. According to Despres, “‘Under the new principles, the machine plans to give away or sell off all the lakefront and to limit protection to the few feet of beach described as ‘lake and shoreline area.’”

Despres went on: “The principles reverse the burden of showing environmental damage. They clearly favor lake defacement and scarring unless someone shows clear proof of environmental damage. The burden of proof should be the other way around.”

This is why Mayor Daley will oddly spout off about protecting the lake and opening up the lakefront to the people at the groundbreaking for a $40 million, 36-story luxury hotel. Note Despres’ use of the word “defacement,” because Daley’s April 24th groundbreaking remarks are a direct retort.

Here’s the picture that accompanied Robert Herguth’s article in the April 25 Daily News on the groundbreaking ceremony, covered in this week’s THIS CRAZY DAY.

Back to Mike!

Mike chews up Mayor Daley’s dog of a speech in his usual lightning prose. After one swift column of type, there’s nothing left but the skull and spine, picked clean.

Mayor Daley, notes Mike, “shared some of his thoughts” on the lakefront. Daley boasted, “No one has defaced our lakefront.”

“He actually said that, and nobody laughed,” writes Mike. “In fact, the hotel executives rapidly beat their palms together.”

Mike recounts Daley’s recent record on the lakefront:

*Meigs Field, then an airport for private planes, built on “an island that was intended for recreation”.

*McCormick Place, which “could have been built almost anywhere” but now takes up the lake at 22nd St, plus all the attendant parking lots.

*What we used to call the “Stevenson spur” coughing cars out onto Lake Shore Drive at McCormick Place from the Stevenson, and also from the Dan Ryan and Kennedy.

*And Jackson Park, where people chained themselves to trees a few years earlier to keep them from being cut down to add four-lane Cornell Drive through the heart of the park.

“The Normandy invasion left fewer scars on the coast of France,” writes Mike.

“That thigh-slapper having been delivered, [Daley] went on to say:

“‘Our plan for the future is to open up the lake to the people.’”

Which people, Mike wonders.

The Illinois Central Railroad people, currently selling the air rights over all their rail yards east of Michigan Avenue along the south bank of the Chicago River?

Or the airline people, chomping at the bit for that lake airport?

“There is no way you can have an airport in the lake without kissing off most of the South Side lakefront. It will turn into Mannheim Rd. on the Water.”

Mayor Daley also oddly talks about having people live downtown, instead of commuting an hour to get to work—though he is at the groundbreaking for a luxury hotel, not a subdivision.

That’s something, writes Mike, that people have talked about whenever “the city administration swept away acres of little houses and replaced them with highrises that were beyond the ordinary person’s means” and “every time urban renewal took something away from the people, giving back nothing.”

“And finally, the stand-up comedian said:

“‘We should be proud of what we’re doing here. Despite all the criticism in the media, what city ever planned a Grant Park?’

Mike’s closer:

“Which city? That’s easy. The same city that will probably destroy a Grant Park.”

Want more Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today? Find it here.

April 30, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by William Juneau

Last month, the Illinois Commerce Commission granted the Illinois Central its wish: a 7% fare increase on its commuter train line serving the South Side, including Hyde Park and Roseland.

But like a bad fairy godmother, the ICC also ordered the IC to “repair and maintain existing stations, put its signal system into a reliable condition, modernize old commuter cars, and see if new train scheduling is needed,” per today’s article—which is a more detailed accounting of the ICC orders than we’ve seen before.

That had to be a response to an earlier Tribune interview with nine top IC executives. The IC executives blamed the current avalanche of IC train breakdowns and delays on its old train cars, but also admitted that they decided four years ago “that no major overhaul work or other major repairs would be made to the old commuter cars. Instead of spending money to rebuild the old cars for 10 to 15 more years of operation, the Illinois Central officials specified that the cars be kept running on a safe basis at a minimum of maintenance expense.”

More ominously for the IC, the ICC set May 9 for a new hearing into “the I.C.’s relationship with its parent company, Illinois Central Industries, Inc., to determine if the conglomerate has worked to the detriment of riders.”

The hearings will take place in the State of Illinois Building, 160 N. LaSalle.

“Cyrus J. Colter, a commissioner, said that the ICC will examine the programs and expenditures for the improvement of service by the railroad, transactions between the railroad and parent company, and utilization of proceeds from the sale of assets.”

“‘Is there an effect of the conglomerate on the commuter operation?’ asked Colter. ‘We don’t know the answer, but we want to find out. It could be that the conglomerate, which also operates soft drink, foundry, and panty hose companies, causes an artificial burden to be placed on the commuter operation.’”

April 30, 1972

Chicago Tribune

no byline

Many independent politicians, as well as groups like Citizens for a Better Environment, are working to stop massive high-rise developments using the air rights for land owned by the Illinois Central in two key downtown lakefront locations: the old site of Fort Dearborn, from Randolph to the river east of Michigan Avenue…

…and the south end of Grant Park, from Michigan Avenue to the eastern edge of the IC train yards, extending south from Roosevelt Road at least as far as McCormick Place at 22nd Street.

Today’s Tribune article, with no byline, mysteriously declares with no attribution that the city has guidelines in place for the IC property south of 12th Street that will require developers “to maintain east-west access across the project at many points using either parks or streets which will lead to the Lake Michigan shoreline.”

These guidelines are supposedly “the same concept of planning used for the Illinois Center project between Randolph Drive and the Chicago River, east of Michigan Avenue.”

However, as we read on April 5-6 in coverage of the last City Council meeting, all the independent aldermen believe the city is about to build a wall of high-rises on the site of old Fort Dearborn and call it “Illinois Center.”

“This is not going to make Chicago great, but grotesque,” said Ald. Seymour Simon.

Today’s anonymous Trib article, again with no attribution, says “The density of the project” south of Grant Park “will be varied, preventing the construction of a wall of high rises along the length of the 104-acre street of land. Two high-density areas—near 11th Place and near McCormick Place—will be separated by low density areas.”

Per this article, the IC and Ogden Development announced they’ll build a hotel, apartment buildings, and an office building on the 12 acres between 11th and 14th.

“A high-density development is planned around McCormick Place to the Stevenson Expressway. The density is lowered again south of the Stevenson Expressway where plans are being formulated for an extension of Michael Reese Hospital complex, housing and shopping.”

May 2, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by Casey Bukro, Environment Editor

The Illinois Central is currently selling off the air rights to two vast areas of its holdings in key lakefront downtown locations—the site of old Fort Dearborn, east of Michigan Avenue between Randolph and the Chicago River…

…and east of Michigan Avenue at Roosevelt Road, the southern edge of Grant Park, extending south at least as far as 22nd Street.

Yesterday, IC vice president of real estate Harold S. Jensen testified at an Illinois Senate agriculture and conservation subcommittee hearing on state Rep. Robert Mann’s proposed Lake Michigan Bill of Rights, which passed the Illinois House last year.

The IC does not like it.

“The Mann bill proposes controversial land-use reforms along a 1 1/2 mile zone bordering the Illinois lakeshore that emphasizes public access and use of shoreline areas,” writes Bukro.

IC VP Jensen told state senators the Mann bill “will stifle development of 85 square miles of the Illinois lakefront.”

Jensen claims lakefront property will lie vacant until comprehensive planning is finished.

“As taxpayers in the state of Illinois we do not think the state should expose itself to the potential liability of hundreds of millions of dollars for the damages to property owners who may be unable to develop their property during or after the preparation of the comprehensive plans called for in the bill,” Jensen testified.

“The most violent outburst during the hearing held in the State of Illinois Building came from Sen. John Knupple (D., Petersburg), in an exchange with a member of Citizens Action Program, who walked out complaining that Knuppel was criticizing the bill as chairman (of the subcomittee).

“Paul Booth, C.A.P. co-chairman, testified that studies show high rise developments do not build tax bases, but are a drain on them because of demands for increased services.”

Booth called for the committee to send the bill to the Illinois Senate floor. U.S. Rep. Abner Mikva also testified in favor of the Lake Michigan Bill of Rights.

May 9, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by Cornelia Honchar

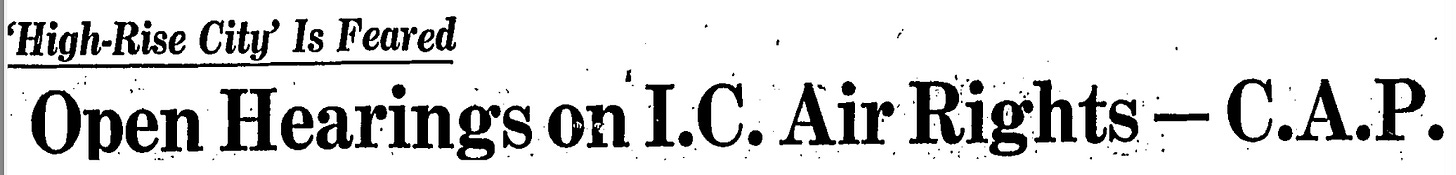

We usually follow the Citizens Action Program (CAP) as it opposes the Crosstown Expressway, sometimes with co-chairman Father Leonard Dubi coming close to a fistfight with U.S. Rep. Roman Pucinski. Today CAP is concerned about the IC’s plans to develop its vast acres between 12th Street/Roosevelt Road and 31st Street.

“The Citizens Action Program demanded yesterday that negotiations between the city and Illinois Central Industries, Inc., on plans for the development of air rights sites on the lakefront between 11th and 31t Streets, be opened to the public.”

Father Dubi’s co-chairman, Paul Booth, handles this one along with 16 other CAP members. Booth and colleagues met with Chicago Planning Commissioner Lewis Hill, “demanding that the negotiations be opened in compliance with the 1967 Illinois Open Meeting Act,” writes the Trib’s Cornelia Honchar. “The talks have been going on for several years.”

“We fear this land will turn into a high-rise city within a city, open only to those who can afford it, and the lakefront will be eaten up,” Booth tells Honchar. But the real point, he says, is that they don’t have access to the documents and meetings notes to see what the city has been privately planning with the IC for several years already.

Lewis Hill says the negotiations aren’t subject to the Open Meetings Act. CAP will have to wait until the city issues its guidelines for the 104 acres of lakefront to the city Planning Commission for review. The Planning Commission sends the guidelines to the City Council for approval.

CAP wants the Illinois Attorney General to sue the city to reveal its negotiations, but Assistant Attorney General Bernard Genis says nope. Genis says only State’s Attorney Ed Hanrahan can handle it, without explaining why.

July 19, 1972

Chicago Tribune

by Keith Bromery

IC chairman William Johnson told an Illinois Commerce Commission hearing that the IC’s commuter line contributes one third of the company’s pre-tax income, but uses two-thirds of the company’s capital funding.

“Johnson…said that the [company] had committed $82 million to the railroad since 1966 with no return.” Even with the recent 7% fare increased approved by the ICC, Johnson says the IC will lose more money in 1972. Johnson says the IC lost $1 million in 1971 ($6.76 million 2022 money), and lost another $1.4 million in the first quarter of 1972.

Money quote:

“We are not being fair to our stockholders. The suburban riders have no right to put their hands into the pockets of our stockholders,” Johnson told the ICC.

Trib reporter Bromery writes that the IC has asked for another rate increase over the next two years, “and has resisted a commerce commission order requiring it to rehabilitate 49 commuter stations and 40 of its present 46-year-old electric cars.”

Meanwhile, Park Forest village attorney Henry Dietch told the ICC that the IC has made money off real estate and air rights on valuable downtown land, and not reinvested any profits into the commuter line.

Dietch is referring to the air rights the IC is selling for the Illinois Center development between Randolph and the River east of Michigan Avenue…

…and the approximately 104 acres of IC land being developed east of Michigan Avenue between Roosevelt Road and 31st Street.

October 11-12, 1972

It’s been All Quiet on the IC Front for the last couple of months, after a year of turmoil—but the IC is ba-a-a-ck.

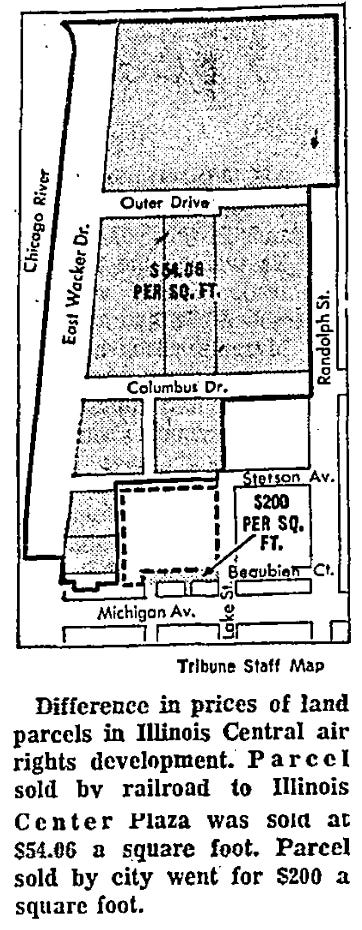

Citizens for a Better Environment has petitioned the Illinois Commerce Commission to halt any land transfers between the IC commuter line and its parent company, charging that the IC sold valuable downtown land to its parent company at a tremendous loss.

CBE research director Duane Lindstrom says the IC sold 83 acres of its rail yards on the site of old Fort Dearborn, east of Michigan Avenue between Randolph and Wacker, to parent company Illinois Central Industries for only $54.06/square foot. At the same time, “Chicago City Council records show that the Council this summer voted to sell an adjacent piece of land on Beaubien Court to the railroad for $200 a square foot,” writes the Trib’s Carolyn Toll.

That means the IC parent company bought land from its railroad for Illinois Center for about 75 % below market value, according to CBE’s Lindstrom.

“We think they knowingly took a tremendous loss, shifting the burden to commuters and shippers,” Lindstrom tells Toll. “If the $54.06 rate had been $200 a square foot, the railroad would have received $447 million on that transaction instead of only $120 million.”

Lindstrom says the ICC “is obliged to see that the railroad is managed in the interests of its consumers and not for the profit of spinoff ventures.”

But IC Industries VP and general counsel Robert Mitten doesn’t think income from selling the IC’s land should go to supporting the railroad’s commuter service. “It has been a losing proposition for a long time, and the over $30 million we’ve committed…the last five years has not been justified,” he tells Toll.

The CBE complaint “seeks to have the (ICC) reconsider its approval of the 1969 land sale,” per the Sun-Times. IC Industries denies it bought the Beaubien Court land at all, because really the land was bought by Metropolitan Structures Corp. “Metropolitan and IC Industries each hold 50 percent interest in Illinois Center Plaza Venture, but the Beaubien Court property is not part of the property being developed in the joint venture,” writes Harsh.

The ICC will hold another hearing on December 19 to investigate the financial relationship between the IC commuter line and its parent company, IC Industries.

October 24, 1972

Chicago Tribune

no byline

The Illinois Central Railroad, which runs the South Side commuter line serving Steve’s childhood and adult homes of Roseland and Hyde Park, has been crying all year that it lost $1 million in 1971 and expects to lose more in 1972, which got them a 7% rate increase from the Illinois Commerce Commission…

…despite an abysmal record for the past year in constant delays and shutdowns.

The IC has also been busy selling expensive air rights for the gigantic Illinois Center development just beginning on its rail yards covering the old Fort Dearborn site east of Michigan Avenue between Randolph and Wacker…

…and about 104 acres of more IC rail yards lining Roosevelt Road east of Michigan Avenue and extending all the way south to 31st Street.

But yesterday, parent company Illinois Central Industries announced third quarter net earnings “increased to $11.4 million, or 63 cents a share, from $10.2 million, or 57 cents a share, in the corresponding period of 1971.”

Also, the IC finished merging with Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad on August 10.

October 26, 1972

Chicago Tribune

no byline

The Illinois Central commuter line that serves the South Side and south suburbs—the IC—racked up 18 serious delays in the last four months of 1971 alone, then piled up at least five more equally bad shutdowns in the first two months of 1972. One day, there was a 30-train back up during morning rush hour, making at least 12,000 passengers late for work.

Top IC executives told the Tribune in an exclusive interview earlier this year that the whole problem is the nearly 50-year-old IC cars, which are being slowly replaced with new double-decker cars. But the executive also admitted that after they ordered the new replacement cars in 1969, they “decided that no major overhaul work or other major repairs would be made to the old commuter cars. Instead of spending money to rebuild the old cars for 10 to 15 more years of operation, the Illinois Central officials specified that the cars be kept running on a safe basis at a minimum of maintenance expense.”

And then they got a 7% fare increase approved by the Illinois Commerce Commission, claiming a $1 million loss for 1971.

Which brings us to today.

“A derailment near the Roosevelt Rd. station of the Illinois Central R.R. caused a major tie-up in the line’s commuter service Thursday, delaying commuters as much as 90 minutes,” report the Trib.

“Hundreds of commuters walked off trains that were backed up behind the derailment, streaming over tracks to the station or into Grant Park to catch buses or walk to their offices.”

This time, the IC doesn’t blame the shutdown on one of the old, antiquated cars about to go out of service. The problem is one of the shiny new double-decker cars, which derailed as it was going through a switch at 11th Place.

“It couldn’t have happened at a worse place,” said the IC spokesman, who said they think the problem was a faulty switch.

“Railroad officials attempted to back up some trains behind the derailed cars to 67th St. but passengers began jumping off the cars, some of them as the trains were moving.”

One IC passenger fumes to the Tribune: “They sat us there for an hour in the yards without saying a thing, not a word about a derailment, which we could understand. Finally some people forced open the door of a car, and passengers began flowing out…The conductor warned the engineer not to move the train but it suddenly began moving while people were jumping off.”

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to this collected post on the Illinois Central from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Plus, regular posts of THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 and Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today. Check it out here.