To access all website contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 is part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. Follow THIS CRAZY DAY on Twitter: @RoselandChi1972.

MONDAY

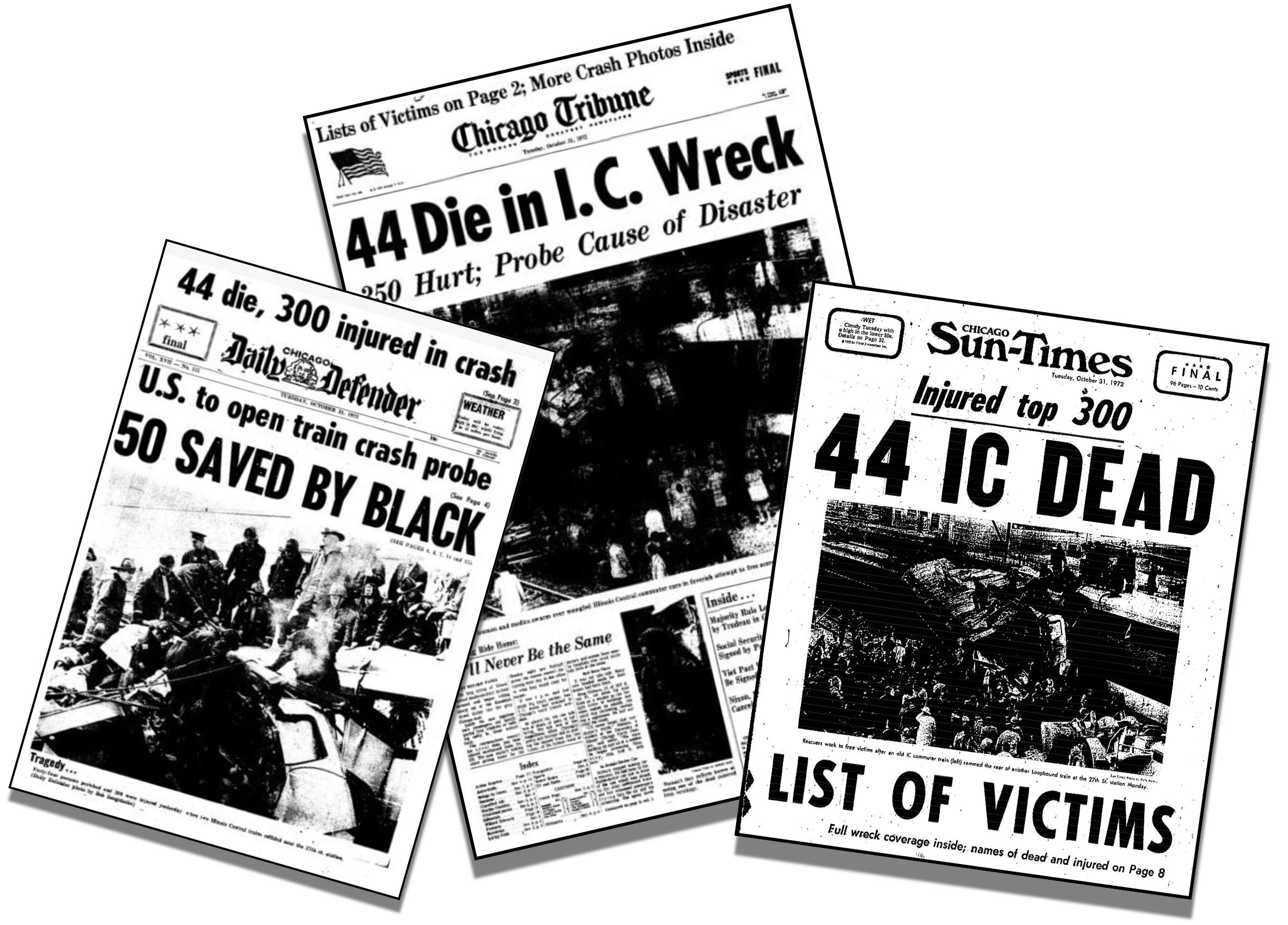

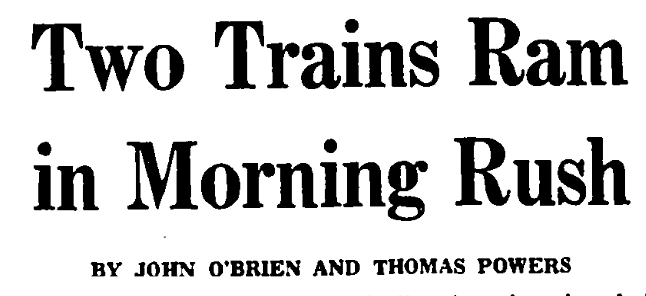

Oct. 30, 1972: The Mighty IC Disaster, Day 1

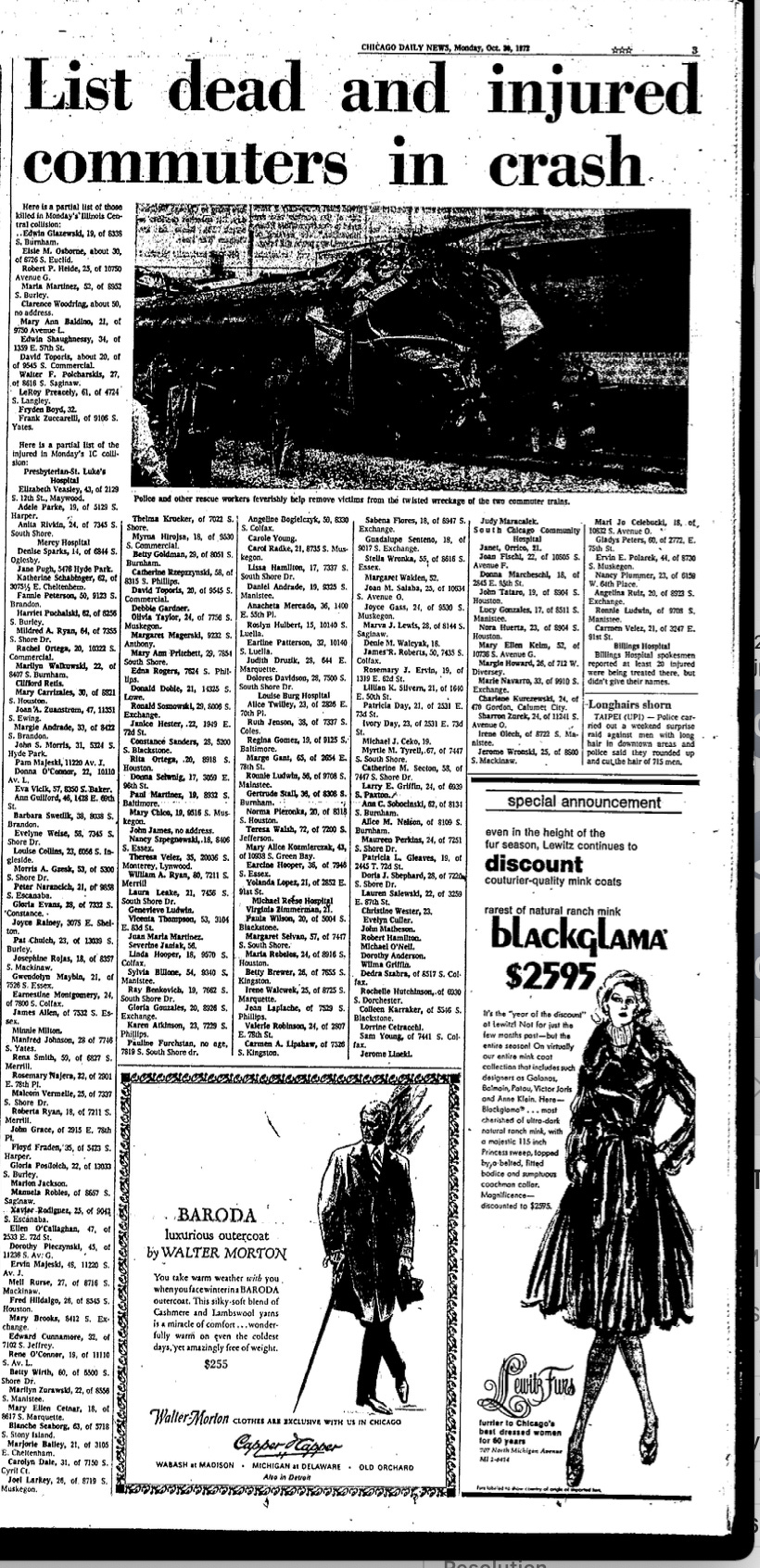

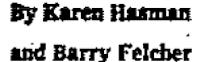

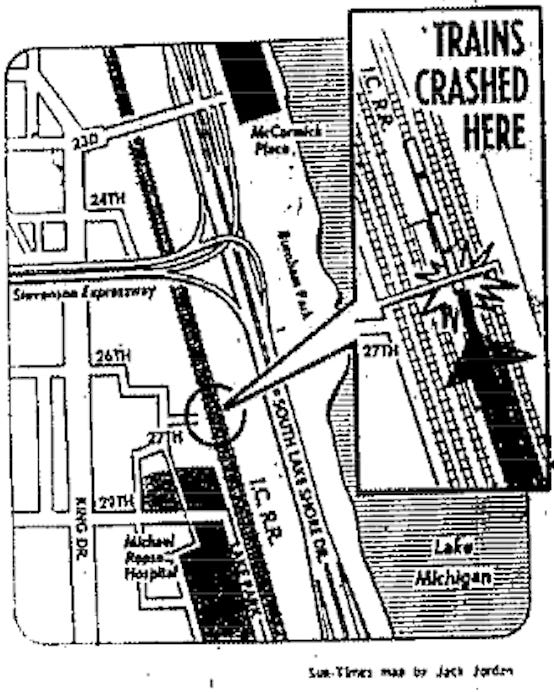

“At least 44 persons were believed killed and more than 300 injured Monday morning when a Loop-bound Illinois Central commuter train rammed the rear of another commuter train at the 27th St. station near McCormick Place.

“The death toll made the disaster among the worst train accidents in Illinois history.”

The lead paragraphs in the Daily News and Chicago Today cover stories are almost identical. The graphs above are from the Daily News.

Chicago Today also puts the accident in more specific context: With the death toll still climbing, this is the worst train wreck in the country since 1958, and the third worst in U.S. history.

It's one of those lines of time and place that separate us: Do you call the commuter train that runs alongside Lake Shore Drive to 47th St. "the IC," or "the Metra Electric?" If you call it the IC, you remember this day. You can't forget it, even if you were a child in 1972.

Monday morning’s IC disaster shows again the advantage afternoon papers still have in 1972, when colossal events happen in time for their deadline. So we begin covering the coverage with Chicago Today and the Daily News, though both papers will be gone in six years.

Chicago Today: “From the air it appeared that the rear car of the first train—a new four-car double-decker—was sliced open, ‘like you put a can opener to it,’ by a following six-car, single-deck train, reported Officer James Cavanaugh from the W.G.N. police trafficopter.

“The double-decker carried about 624 passengers, and the second train 504 passengers.”

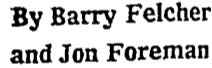

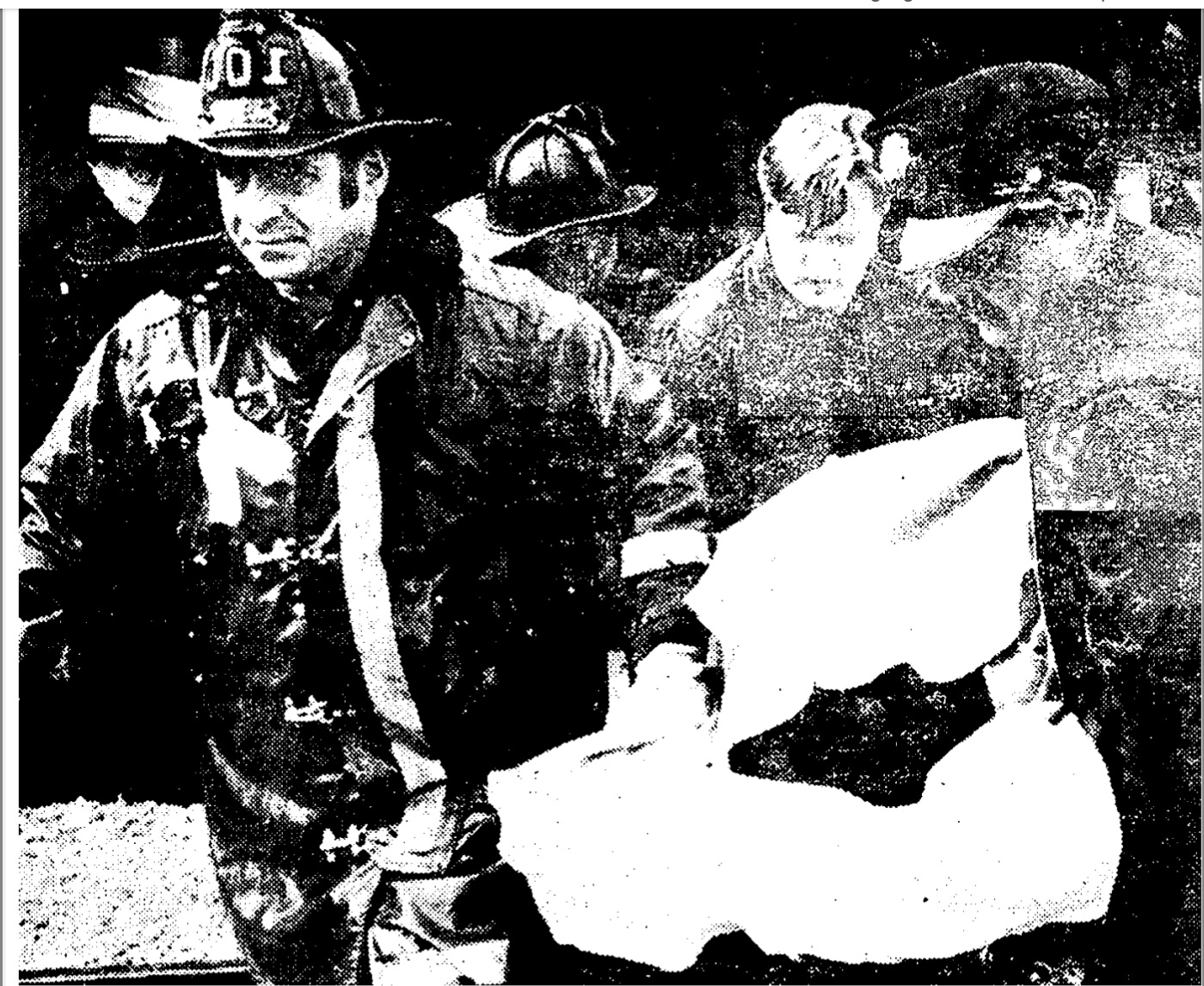

Daily News: “Sweating, grunting and cursing firemen from all over the city used winches, tackleblocks and other equipment to rip loose large hunks of twisted sheet metal and free persons trapped inside.”

Both papers immediately add this grim detail, here from the Daily News:

“Many passengers, including some who were seriously injured and maimed, were trapped for hours in the tangled wreckage of the two crowded rush-hour electric trains.”

Let’s break to recap the Illinois Central and its already tumultuous year. To skip directly to finishing today’s coverage, scroll down to “Back to 1972” or click here.

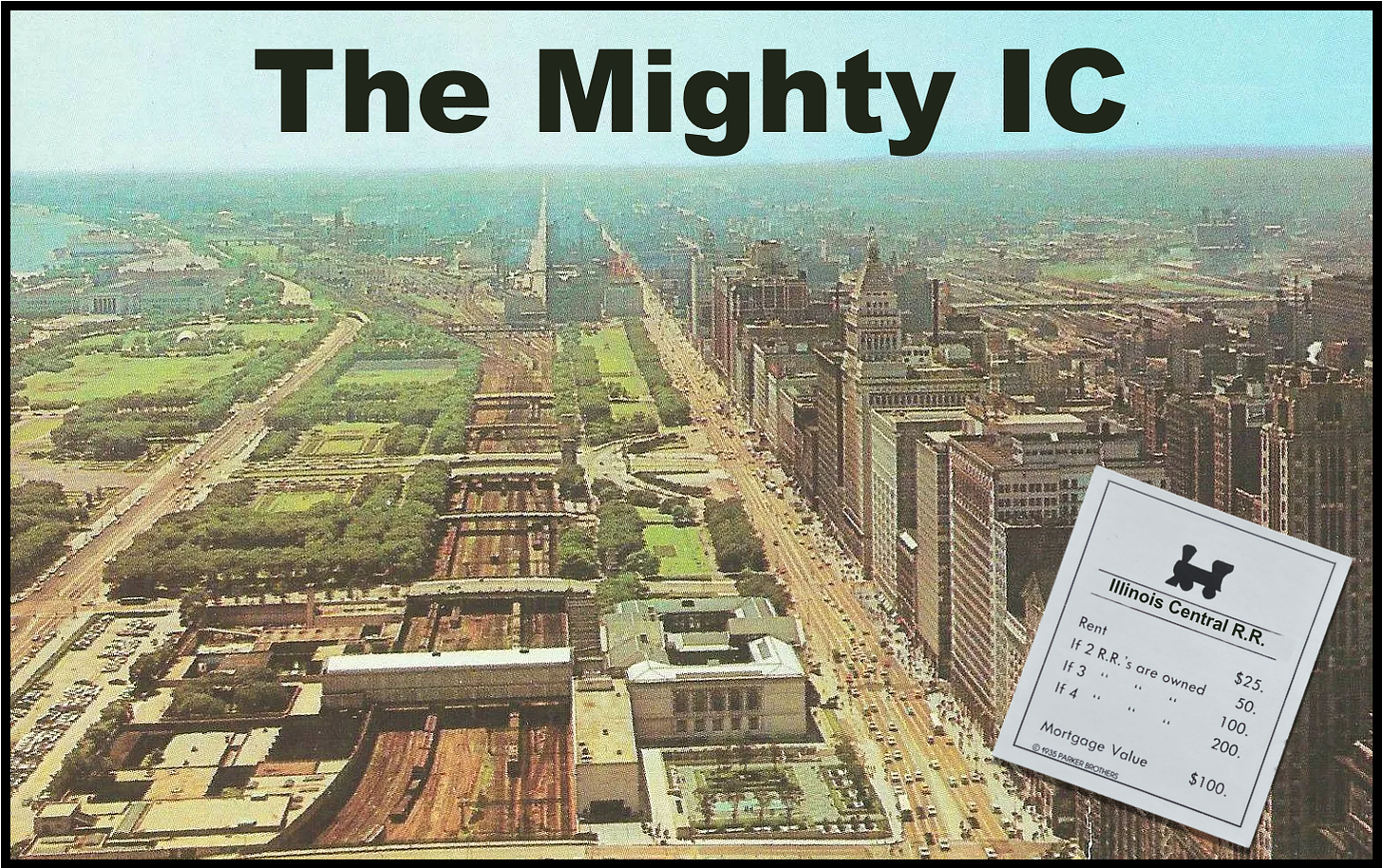

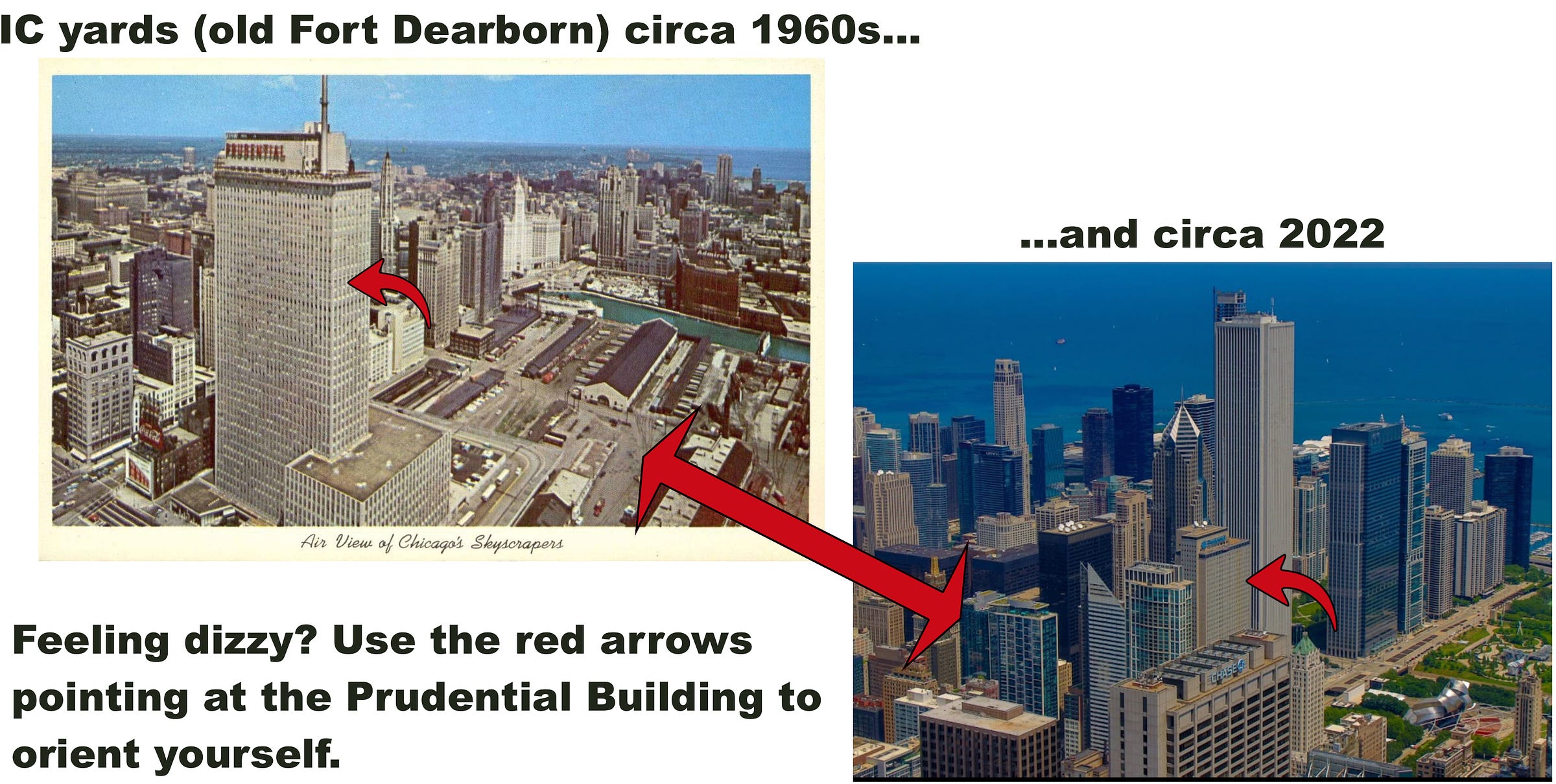

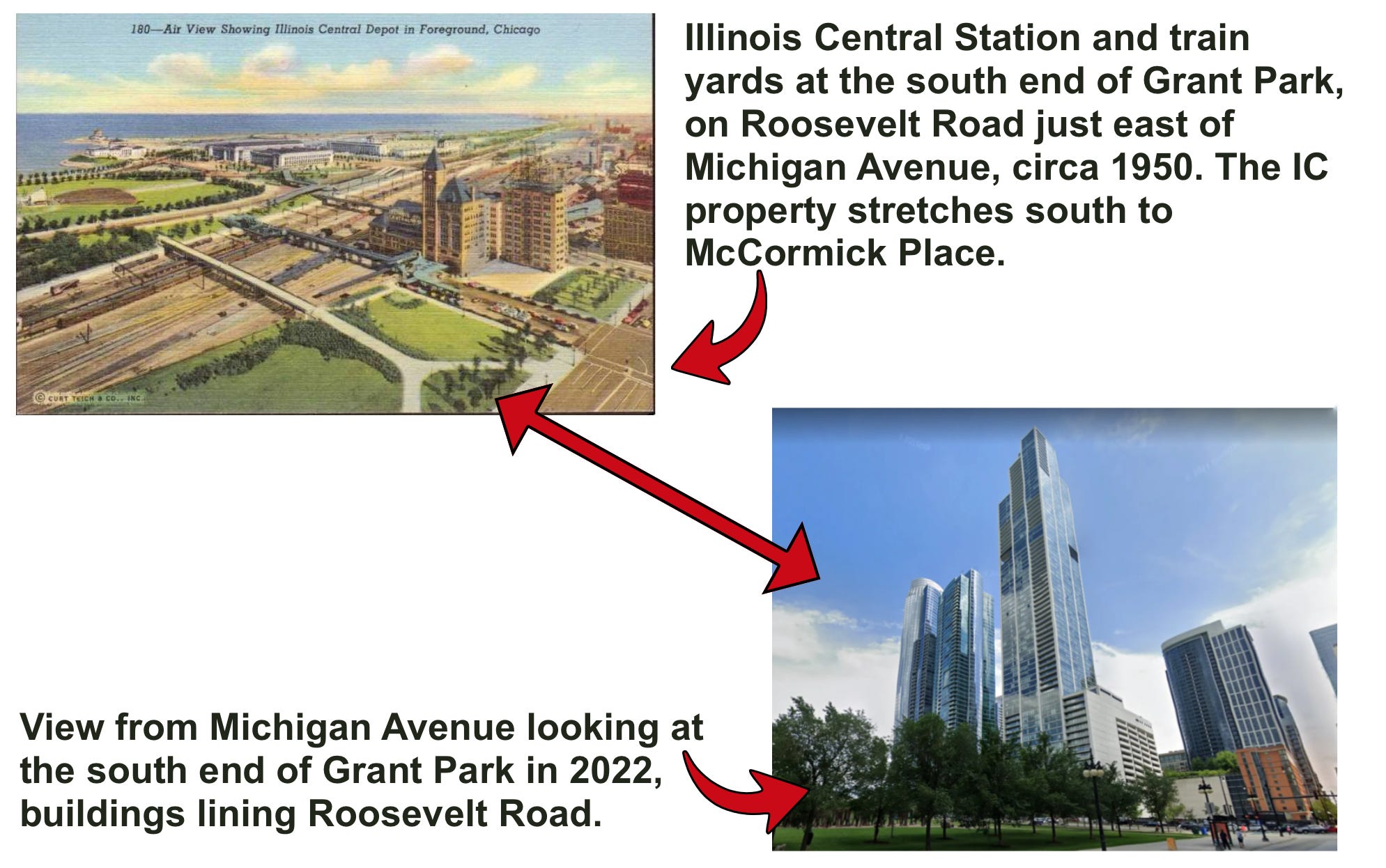

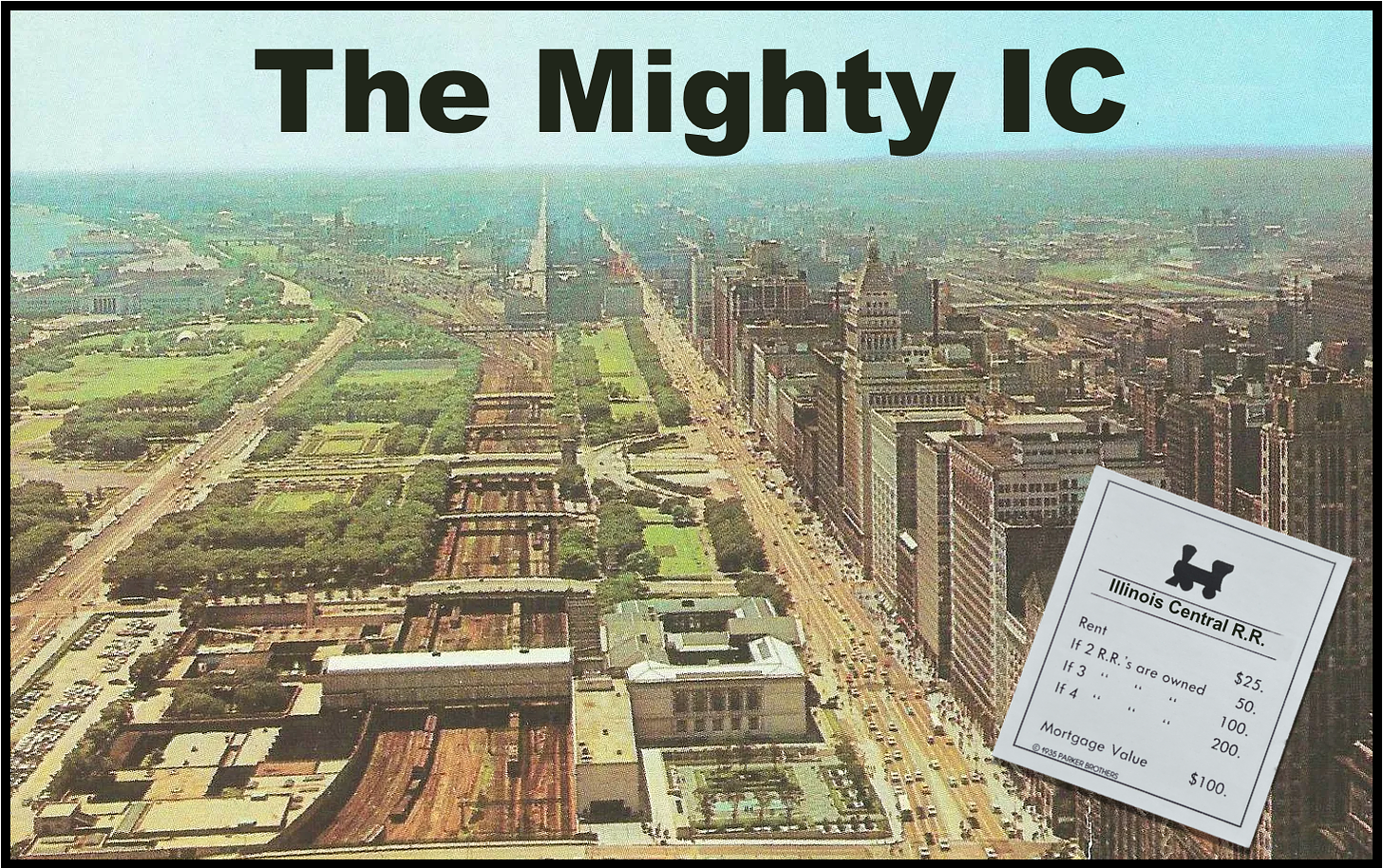

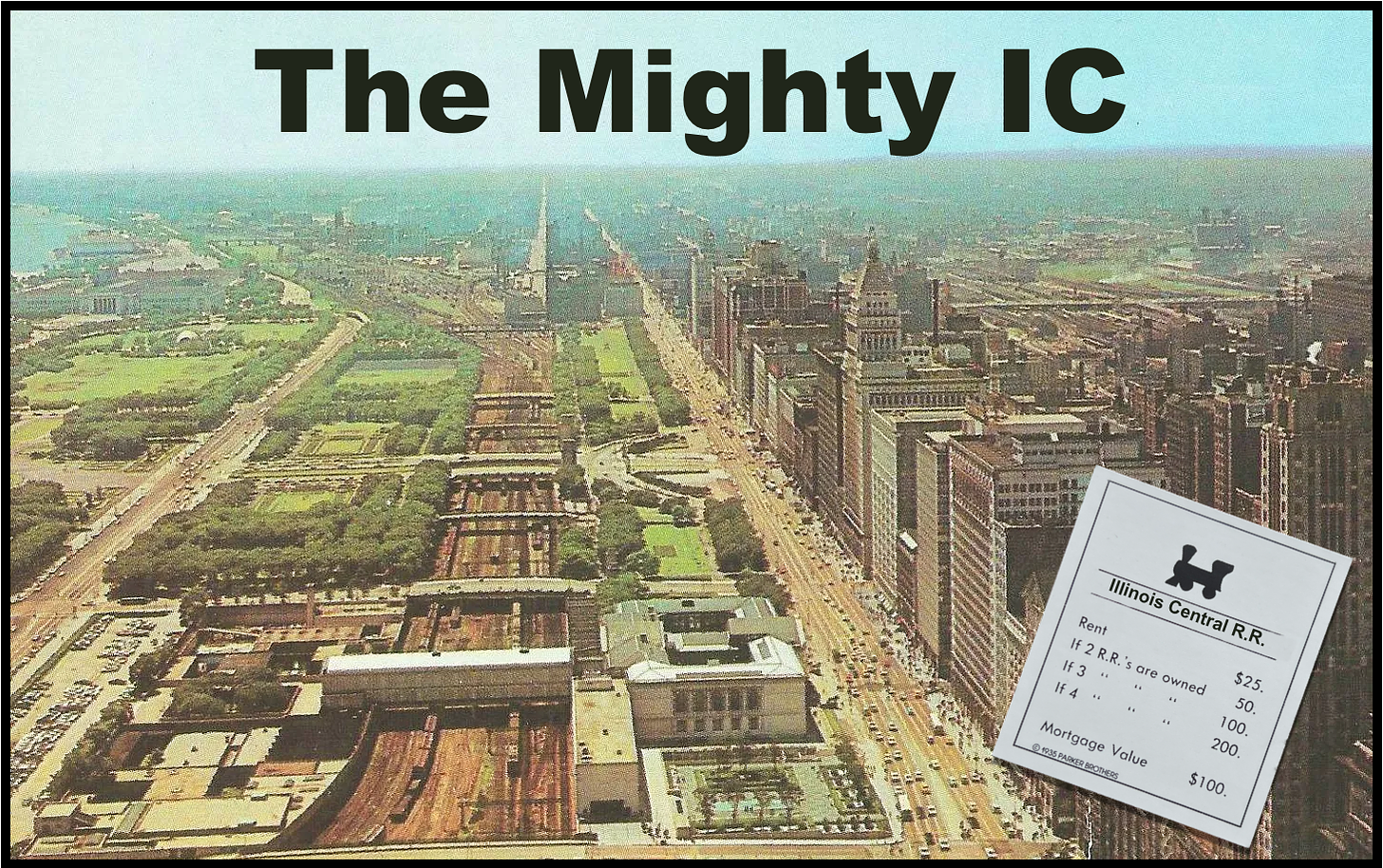

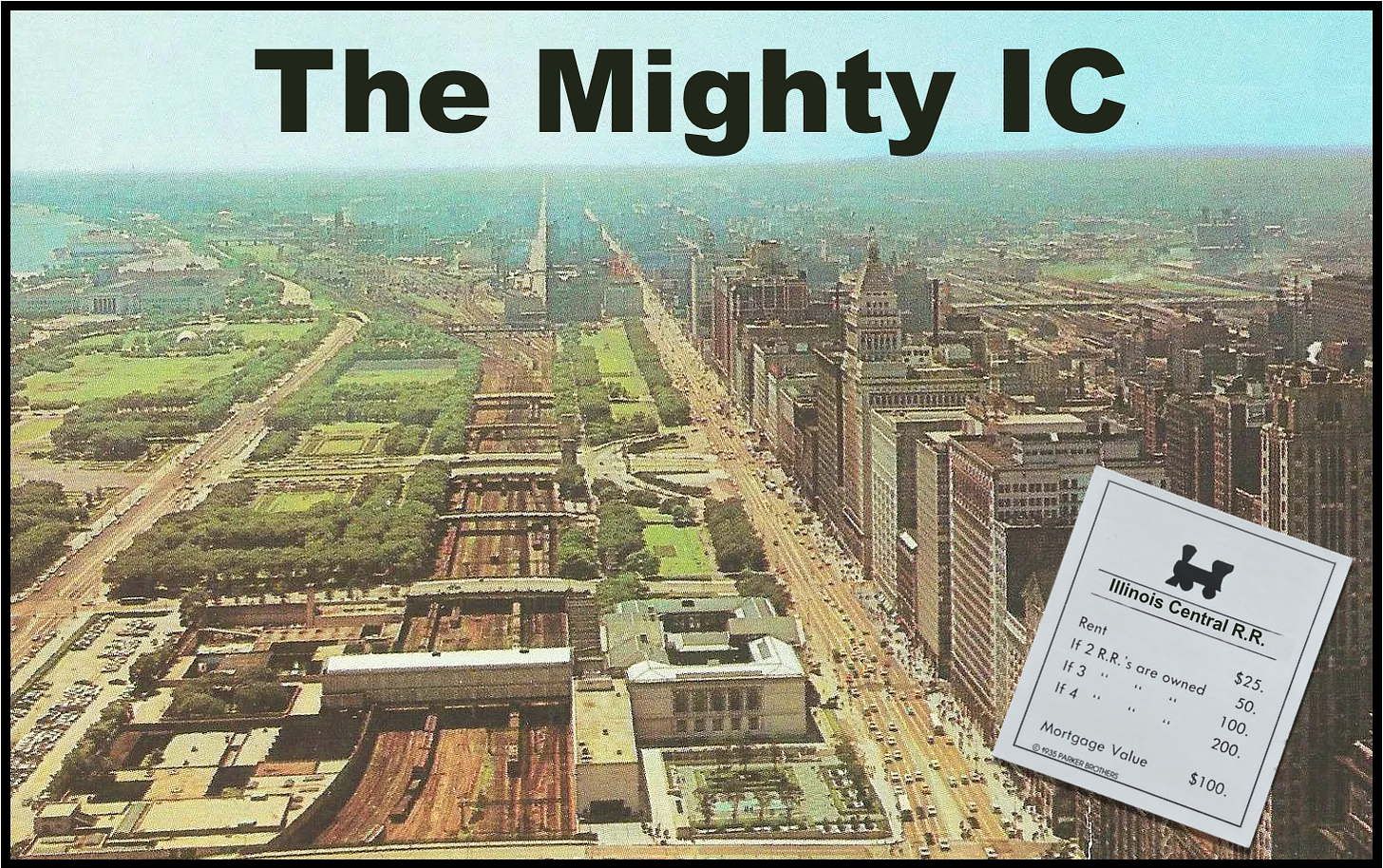

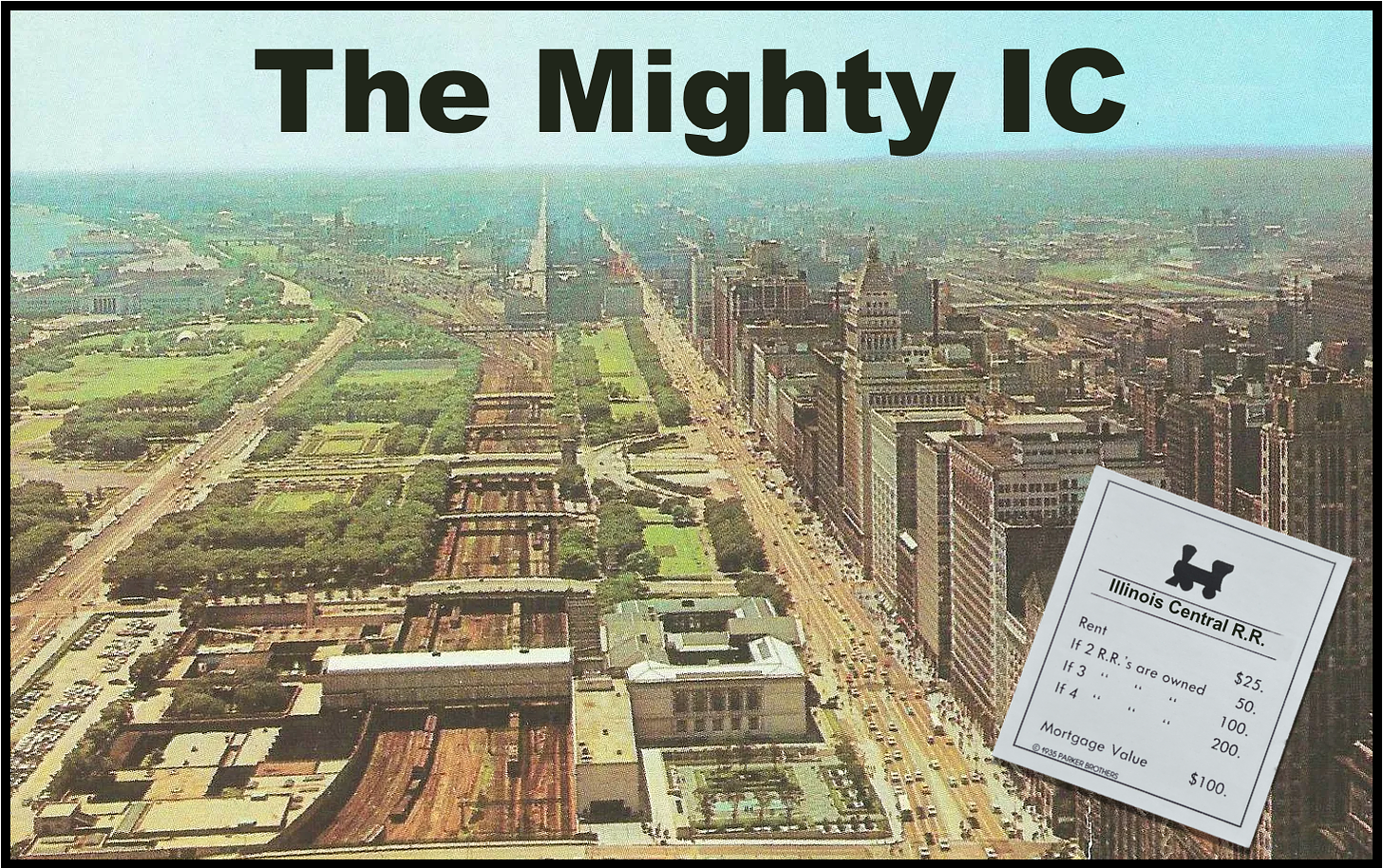

The Illinois Central Railroad literally runs right through the beating downtown heart of Chicago—and the South Side. You can see in the Mighty IC logo above how the IC tracks rush through the city’s front yard in Grant Park one level below grade, as if they’ve carved out a rock canyon through years of service. That’s fitting, because the IC is integral to the city’s history. See here for an extended version.

Here’s another view:

You probably know generally that 19th century Chicago beat out other Midwestern cities like St. Louis to become the country’s central hub for transportation and, thus, trade. But that didn’t happen automatically just because Chicago sits on the shores of Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Chicago River.

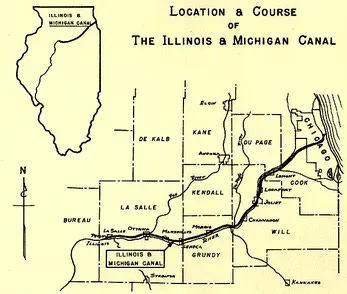

Chicago took the lead first thanks to the Illinois & Michigan Canal, which opened in 1848 and connected the South Branch of the Chicago River with the Illinois River, between Bridgeport and LaSalle-Peru. The I&M linked Chicago to the Mississippi River and created an unbroken water route from New York to the Gulf of Mexico for the first time.

As Donald L. Miller writes in City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America, the I&M Canal created the longest inland waterway in the world, making it “virtually certain the city would become a major rail center.”

Railroads were conquering the country in the mid-1800s, so becoming the nation’s rail hub was integral to Chicago’s rise. The Illinois Central made that happen. The IC “had the earliest and longest-lasting effect on Chicago’s physical environment,” writes Miller.

Newly-minted U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois had gone to Washington in 1846 determined to get federal legislation establishing the Illinois Central, to run the entire length of the state and on to the Gulf of Mexico. Douglas didn’t just succeed—he added an IC branch to his new hometown, Chicago.

“In 1856 the 705-mile-long railroad from Chicago to Cairo, the longest in the world, began regular service, and Chicago immediately felt its impact,” writes Miller. “Trade on the upper Mississippi that had previously gone downriver to St. Louis was rerouted by rail to Chicago, whose boosters began calling the Illinois Central ‘the St. Louis cutoff.’”

In 1972, among other things Illinois Central Industries runs the the IC commuter line serving the South Side and suburbs. The IC is owned by Metra by 2022, renamed the Metra Electric. Steve took the IC from Roseland as a child to see Marshall Field’s Christmas windows with his family. Grownup Steve takes the IC/Metra Electric from Hyde Park to his office at Rose & Rose, on the 13th floor of the IBM Building.

The picture below, from 1975, shows the IC’s aging single-deck cars at the lefthand platform, and its new double-decker orange-and-silver cars at right. The new double-deckers were ordered in 1969. They’re just now starting to be delivered by the manufacturer in 1972, a few cars per month.

Meanwhile, the single-deck cars are 46 years old, and literally falling apart. Train malfunctions, derailings and other delays have been tormenting IC customers since 1971. A few headlines tell the tale:

The IC blames the old cars. But IC executives also admitted in a February Tribune interview that when they ordered the new double-decker fleet, they “decided that no major overhaul work or other major repairs would be made to the old commuter cars. Instead of spending money to rebuild the old cars for 10 to 15 more years of operation, the Illinois Central officials specified that the cars be kept running on a safe basis at a minimum of maintenance expense.”

In February, Chicago Today marketing columnist George Lazarus wrote an op-ed about the lousy IC service he suffers commuting from Flossmoor. Lazarus and a Daily News letter writer both voiced the common suspicion that the IC is purposely screwing up to persuade the Illinois Commerce Commission to grant its request for a 7% rate hike.

The Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC) began investigating the awful IC service last year. The ICC has been holding regular hearings about the IC all year in 1972.

The ICC granted the IC’s requested 7% fare increase--

—but also “ordered it to make immediate improvements in its equipment, maintenance, signal system and stations,” reported the Daily News. The IC has been fighting that ICC order ever since.

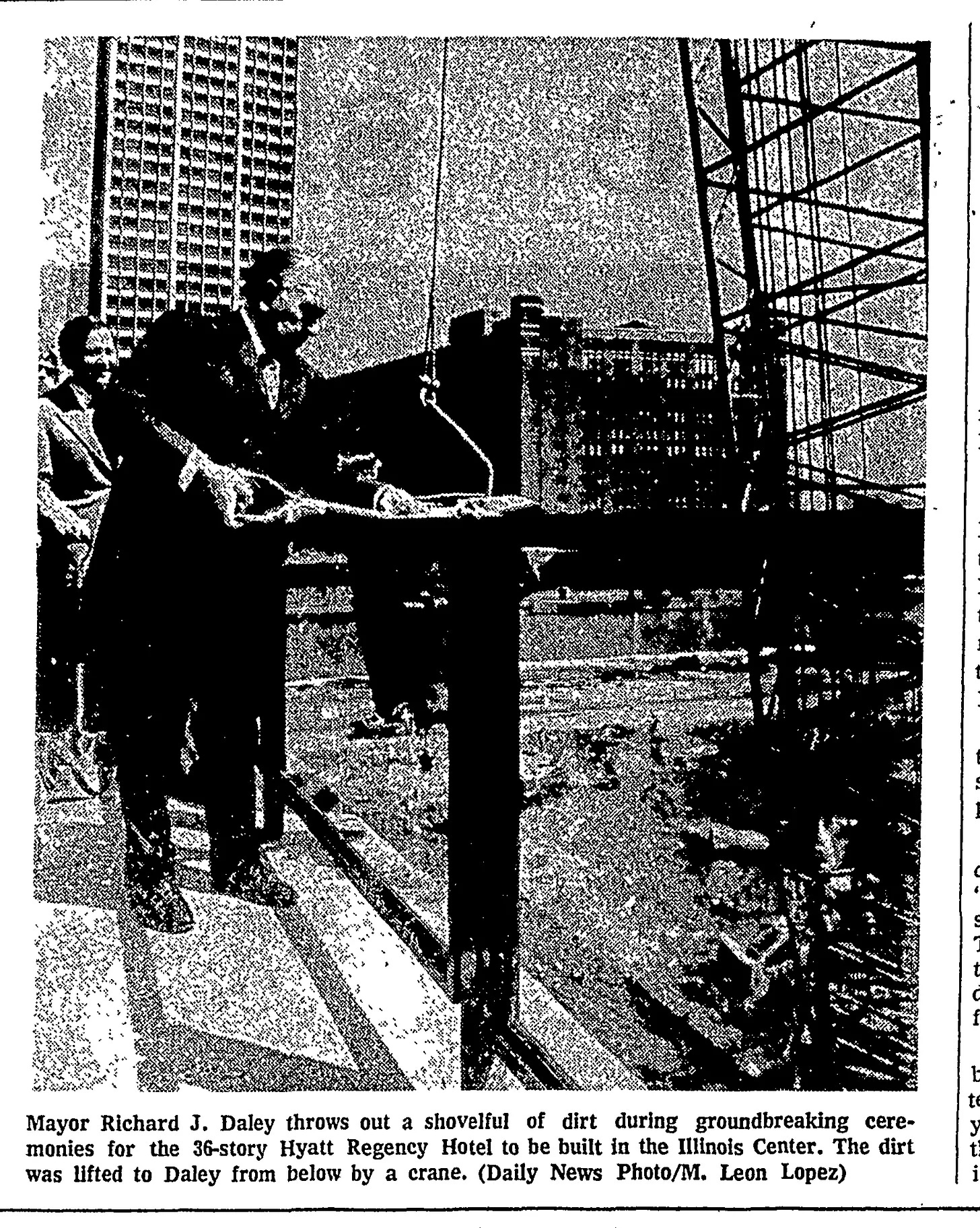

Meanwhile, many Chicago politicians and community groups are worried that walls of high-rises are about to spring up and block Chicagoans from the lakefront in two key areas where the IC is profitably selling its air rights for gigantic developments.

The IC is selling off the air rights for its rail yards on the site of old Fort Dearborn, starting with the land that is already sprouting Illinois Center—

—and the IC is also planning developments on its holdings at the south end of Grant Park, fronting Roosevelt Road and stretching back to McCormick Place.

Pushed by politicians like Illinois Representatives Anthony Scariano and Robert Mann, along with community groups like Citizens for a Better Environment and Citizens Action Program, the ICC began another series of ongoing hearings looking into the financial relationship between the IC commuter line and its parent company, Illinois Central Industries.

As Rep. Scariano put it, he wants to “try to find out why the profit from the sale of expensive downtown property, including air rights, by the IC are not applied to the railroad’s commuter operations.”

Nonetheless, the IC is seeking another rate increase over the next two years. In July, IC chairman William Johnson complained at an ICC hearing that the IC commuter line is a drain on the company. “We are not being fair to our stockholders. The suburban riders have no right to put their hands into the pockets of our stockholders,” Johnson told the ICC.

Last week, train No. 320 derailed near 11th Place, which the IC blamed on a bad switch.

“Hundreds of commuters walked off trains that were backed up behind the derailment, streaming over tracks to the station or into Grant Park to catch buses or walk to their offices,” per the Daily News.

It turns out No. 320 is the same train that slammed into the double-decker cars at 27th Street today.

Back to 1972

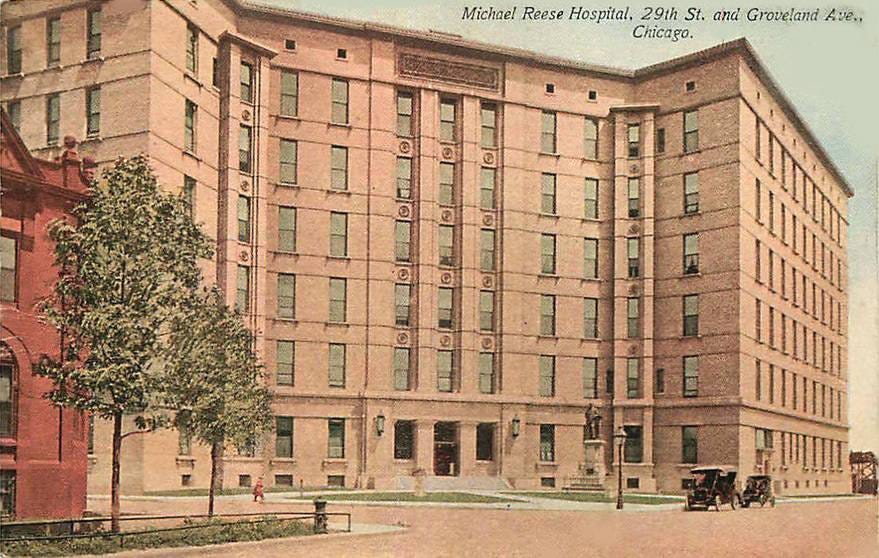

In a twist of luck, if we can use that term for such a tragedy, the crash happened right behind the now defunct and demolished Michael Reese Hospital, which all IC passengers seated on the west side of the train saw every time they rode downtown. Mercy Hospital is several blocks away, and Billings Hospital, the original unit of today’s University of Chicago Hospital, is a quick drive almost directly south on 59th Street.

Chicago Today columnist Jack Mabley rushes to the scene and focuses on Michael Reese personnel attending to victims. Mabley is the most prominent columnist in town after Mike Royko, which is ironic since Royko got a shot as columnist almost 10 years ago because Mabley quit the Daily News for Chicago’s American, which turned into Chicago Today.

“The city’s rescue machinery was still mobilizing,” writes Mabley. “White-clad doctors, nurses, interns, and medical students from Michael Reese Hospital were running across the I.C. tracks toward the wreckage. They carried morphine and syringes in small white boxes under their arms.”

Mabley spends time on the platform with some victims waiting to be carried away by stretcher, as well as unconscious victims stretched out about 20 feet away.

“Arms and legs were twisted grotesquely, and blood covered most faces. Those who weren’t unconscious were given merciful relief with a shot of 10 milligrams of morphine.

“A white-clad woman medic pumped violently on the chest of an unconscious woman on the platform as firemen watched anxiously.

“In spite of the incredible physical chaos, there was no confusion. There weren’t enough ambulances even an hour after the crash. The bodies were along the railroad siding, some entirely covered with blankets, some with unseeing eyes in bloody faces at one end of the stretchers, and mangled legs at the other.

“Dr. C. Barros was on duty at the hospital when the public address system called out Reese’s disaster plan.

“‘We’ve rehearsed for this,’ Dr. Barros said. ‘We were ready. Everybody possible raced to the crash. We administered morphine and helped pull people out of the wreck…No, the morphine doesn’t knock them out. It stops the pain immediately. It lasts two or three hours.’”

…. “He was the calmest man at the scene. Helicopters roared overhead. Sirens shrieked as ambulances carried victims away and empty ambulances returned for more of the injured…..Some of the bodies being carried out under sheets weren’t even in human form. They were round figures under sheets.”

“Firemen ran across the tracks to pick up huge wooden ties, probably 10 by 10, and prop them against the leaning wreckage so it wouldn’t fall over onto the firemen, policemen, workers, and doctors.”

Back to the Daily News and Chicago Today cover stories:

Patrick Townsend, a passenger on the first train of double-decker cars, tells Chicago Today that 27th Street was a “flag stop”—not a regularly scheduled stop, but a passenger on the platform can flag down the train.

“Apparently someone [on the platform] held his hand up at the last moment,” said Townsend. “The train overshot the platform by about 15 feet. The conductor told the engineer to put the train in reverse.”

The IC’s initial explanation comes from Jack Humbert, Vice President for operations. Humbert says the first train, the new double-decker, overshot the 27th Street station platform, tripping a warning light 1 1/2 miles south down the tracks, turning it from red to yellow.

Then the first train backed up in order to line up with the platform, which turned the warning light back to red.

“But by that time, the second train,” the older single-deck train, “had already passed the signal,” per Today.

So the second train kept coming, though it had slowed to 30 m.p.h. after seeing the yellow light.

The conductor of the double-decker new first train was in the last car. When the train overshot the platform, the conductor called the engineer over the intercom and told him to back up to platform. Then the conductor looked back and saw the single-deck old second train coming. He called the engineer back and told him to stop. Realizing the trains would collide, the conductor leapt out the back door. Per Chicago Today, the conductor was still injured, but we don’t hear his condition.

George Richardson was riding in the front car of the double-decker first train. He tells the Daily News he heard a voice come over the intercom and tell the engineer to back up.

“About a minute afterward, there was another order over the intercom,” says Richardson, of 6953 S. Merrill. “Someone said, ‘Hold it.’ That was the only thing he said. I couldn’t really analyze the tone, but it sounded like they wanted to hold it in a hurry. It was just a few seconds later that the impact came. It was just a big jolt. Everyone got thrown forward.”

“Motorman Robert Cavanaugh of the second train was finally removed from his tiny compartment at the head of the lead car about 3 1/2 hours after the collision,” writes Chicago Today. Cavanaugh was conscious, but couldn’t talk according to a doctor at Billings Hospital, where Cavanaugh was flown by fire department helicopter.

“Mayor Daley and Fire Commissioner Robert J. Quinn were on the scene almost simultaneously with the first emergency squads,” writes Today.

“Daley, standing with his bodyguards at the east side of the wreckage, watched firemen and emergency crews work to free the injured passengers,” writes the Daily News. “An IC employee burst past the bodyguards and went up to the mayor and said, ‘Mr. Cavanaugh, the engineer, a good Irishman, was in there.’ Daley nodded in acknowledgement.”

Both engineers were veterans with the IC.

“One unidentified fireman at the scene said, ‘The last time I saw something like this I was in Bonn during World War II.’”

Per the Daily News, the later IC trains were backed up 40 blocks to 67th Street.

“It was like a battlefield,” write Felcher and Foreman.

“The violence had ended, and the medics had taken over.

“‘More morphine, more morphine,’ yelled nurses as they tended to seriously injured passengers….Half a dozen bodies—only some of the dead—had been covered and placed neatly together at one side of the tracks.

“For half an hour, a red-headed woman screamed as she lay pinned beneath the lead car of the moving train that had slammed into one stopped at the station.”

“A woman was carried from the wreckage on a stretcher, with blood covering her head and no shoes on her feet. Somehow, she managed to smile and wave her hand.”

“The Fire Department chaplain said he had performed the last rite for four or five persons inside the standing train. ‘I couldn’t find any heads on a couple of them,’ he said.”

“Sirens wailed continually as half the city’s ambulances rushed to the crash scene.”

“Hundreds of commuters from other trains that had stopped for the accident walked down the right-of-way and were directed to the sidewalk at the crash scene. Many kept walking toward the Loop, a couple of miles away.”

“The only warning the passengers on the 7:15 South Chicago train had was the screech of locked metal wheels on the steel rails.

“Then they were flying through the aisles. ‘They were coming from everywhere,’ said Glorio Gonzalez, 20, a passenger on the 7:15…. ‘There was blood everywhere.’”

Mrs. Mary Brooks, 19, of 8412 S. Exchange, was riding on the single-decked old train.

“I was riding in the front of the first car when we approached McCormick Place,” she tells the Lu Palmer or Edmund J. Rooney. “The engineer came out—he’s a real nice man—and told us to get down, that the train was going to crash. Then he hit the floor, and the train crashed.”

“In the final reckoning it comes down to luck.

“Some live. Some die. Some are scarred or disabled for life.

“There was no rational explanation, after the Illinois Central train disaster Monday, for the fine line that separated victims from survivors.

“‘This was the bizarre thing—the number of dead bodies around the live ones,’ said Dr. Peter Rosen, one of the doctors on the scene. ‘It’s a matter of luck who gets killed and who doesn’t.’”

Dr. Rosen is emergency room director at nearby Billings Hospital, now University of Chicago Hospital. He jumped in his car and drove straight to the crash, where he crawled underneath the wreckage of the lead car of the second train, which had crashed into the the first train.

“He found a young woman named ‘Sue’ and stayed with her for about a half an hour.

“‘She was hanging with her head down. A fireman was holding her head. He had started to give her an IV. She had trouble breathing. We put some oxygen on her for a while and gave her 10 micrograms of morphine.’”

Sue was freed three hours later and taken by helicopter to Billings.

Between the two papers, we get stories both of one regular IC passenger who missed the accident because she got on a later train, and one passenger who was in the accident because he took an earlier train than usual.

“Marie Kavel is alive today because she took a later train so she could smoke on her way to work.

“Her brother, Robert Heide, was among those killed in today’s Illinois Central Railroad wreck.

“Marie, who suffered cuts on her leg, was on the train that smashed into the one carrying her brother.

“After being treated at a nearby hospital, Marie, 30, was taken to her home at 10750 S. Avenue G. A relative told this story:

“‘They both work downtown. He got on the first train, but she waited for the second one so she could smoke.”

(This might mean that Marie wanted to stay and smoke on the platform, or it might mean that she knew the next train had a smoking car.)

…. “Robert, 25, of the Avenue G address, was employed by a Loop insurance firm. He wanted to be a teacher and was attending Olive Harvey Junior College.”

And from “Who lives, dies a matter of luck” from the Daily News, by Karen Hasman and Barry Felcher, we meet Robert Johnson of Hyde Park “as he sat in a wheelchair at Michael Reese Hospital, overlooking the scene of the crash.”

Johnson left for work a half hour earlier than usual this morning, “so he could pick up a roll and a cup of coffee before work.”

“Johnson, chief of legal services for the Office of Economic Opportunity in Illinois and Indiana, escaped with cuts and bruises. But he was confined to a wheelchair by a leg injury.

“Johnson was a passenger in the train that was standing in the station when it was struck from the rear.” He was in the last car, the one that took the direct impact of the second train.

“I looked out and saw another train coming from behind,” he said. He was standing in the aisle, and started running toward the front of the car.

“I was thrown to the floor. Glass and dust and all sorts of materials kept coming down on top of me. It just seemed to go on and on. I remember thinking, ‘Isn’t it over yet?’ I don’t remember hearing much noise. I may have blacked out.

“I could see what looked like bodies all over. Lots of people were encased by bars and partitions. There was a lot of horror in that car. Two or three other passengers helped me out. I couldn’t stand.”

“Seated in his wheelchair at Michael Reese, three hours after the crash,” Johnson had coffee and a roll. “I finally got it,” he said.

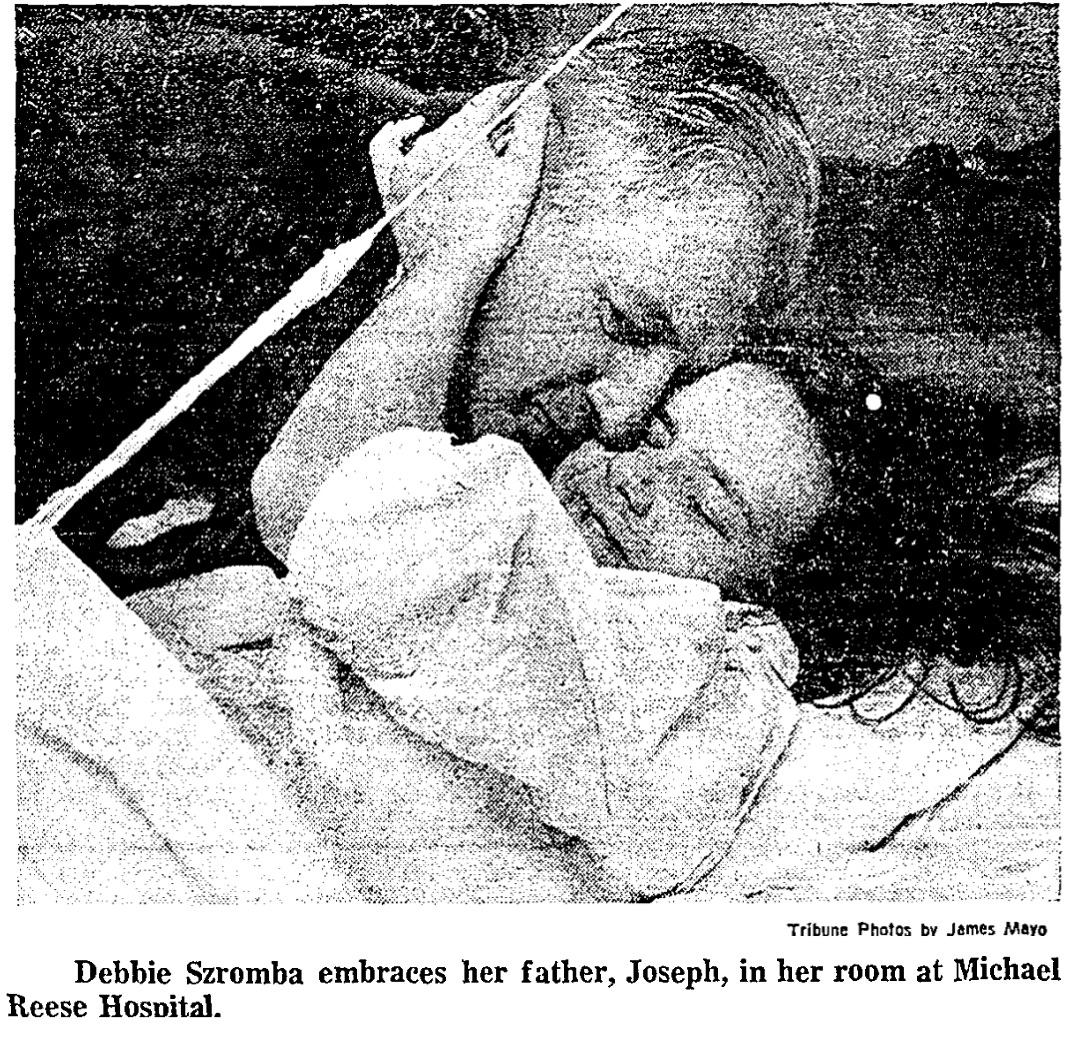

Daily News reporters Keith Bromery and Edmund J. Rooney brought Chicagoans the first story on two girls who would become symbols of the IC tragedy, though today they are not named.

“Nearly 100 Chicago firemen worked for more than five hours Monday in a dramatic effort to rescue two girls who were trapped in the twisted wreckage of the two Illinois Central commuter trains.”

The girls were seated just ten feet from the front of the first car of the second train, the one that crashed into the double-decker train stopped at 27th Street.

“The rescue effort proceeded cautiously because firemen feared that a big shift in the wreckage would kill the two young girls, according to (Fire Marshall Harold) Prohaska.

“Three giant cranes were maneuvered into position to help pull the wreckage off the girls.

“‘Take it up easy John, take it up easy,’ one of the crane operators was told by radio.

“Firemen used hacksaws, chains, picks, hammers and clawed debris with their hands in an effort to rescue the girls.

Mayor Daley watched the nearby, along with Police Supt. James Conlisk and U.S. Rep. Roman Pucinski. A Fire Department helicopter was kept nearby to fly the girl to Billings Hospital.

October 30, 1972

Chicago Daily News: Letters to the editor

CTA and parking stories just never reach their expiration date.

Note: That $4.15 for three hours and five minutes would be $28 in 2022. And that is ridiculous, even by 2022 standards. I won’t pay more than $18 to park for the entire day in a lot. And the insane street rates foisted upon us by the Faustian deal made by Mayor Daley II with a private contractor is $7/hour in the Loop—which would still only be $21 for M. Yellin. Unless M. Yellin got back to the car five minutes late and got a ticket too.

October 30, 1972: De Mau Mau Week 3

Chicago Daily Defender: De Mau Mau letter

On October 15, Chicago was hit with a weeklong blitz of horrifying headlines about an alleged terrorist group of Black Vietnam veterans bent on randomly killing white people, possibly numbering up to 3,000 members nationwide.

For a full rundown, see the introduction to Mike Royko’s October 16 column on the topic or scroll through that week’s TCD1972, reading the daily coverage under the De Mau Mau heading. For a recap of the original horrifying crimes involved, see here. It began, for newspaper readers, when four members of the Corbett family were executed in their Barrington Hills mansion’s pantry in August.

The sensational coverage quickly drew criticism from Black leaders. The papers were pulling back on De Mau Mau coverage by the end of the first week, with nearly all the weekend coverage consisting of stories about the criticism, not the story itself.

By week two, the story had fallen off a cliff—certainly off the front pages. Criticism and newspaper self-criticism continued, with no news until Wednesday-Thursday October 25-26. Those stories were stuffed far back in the paper. Nobody was arguing anymore that a nationwide group of thousands of Black Vietnam veteran were hunting random white people, but the guilt of the arrested men began to look more possible as suspect William “Butch” Jackson testified at a preliminary hearing about the Corbett murders, and the case was sent to a grand jury. Three detectives testify that four of the suspects admitted participating in the Corbett murders and gave oral statements, though only one signed a confession.

October 30, 1972

Chicago Sun-Times: Women’s girdles for pants

Last week, I noticed how prevalent ads still are for girdles—the kind you expect to see in 1930s through 1950s ad or movies—and included a few, like this one:

This week, I noticed that the girdle manufacturers must have figured out that their product is going the way of men’s hats (and buggy whips earlier this century). The girdle manufacturers must be hopeful that this is not because women have figured out how awful girdles are, but only because they are wearing pants.

In looking back to last week, I realized that I’d already included a Sears ad for a pants girdle without even noticing the shift. I’m surprised they’re not advertising girdles for hot pants. The pants girdles do come in capri length, after all.

October 30, 1972

Chicago Daily News

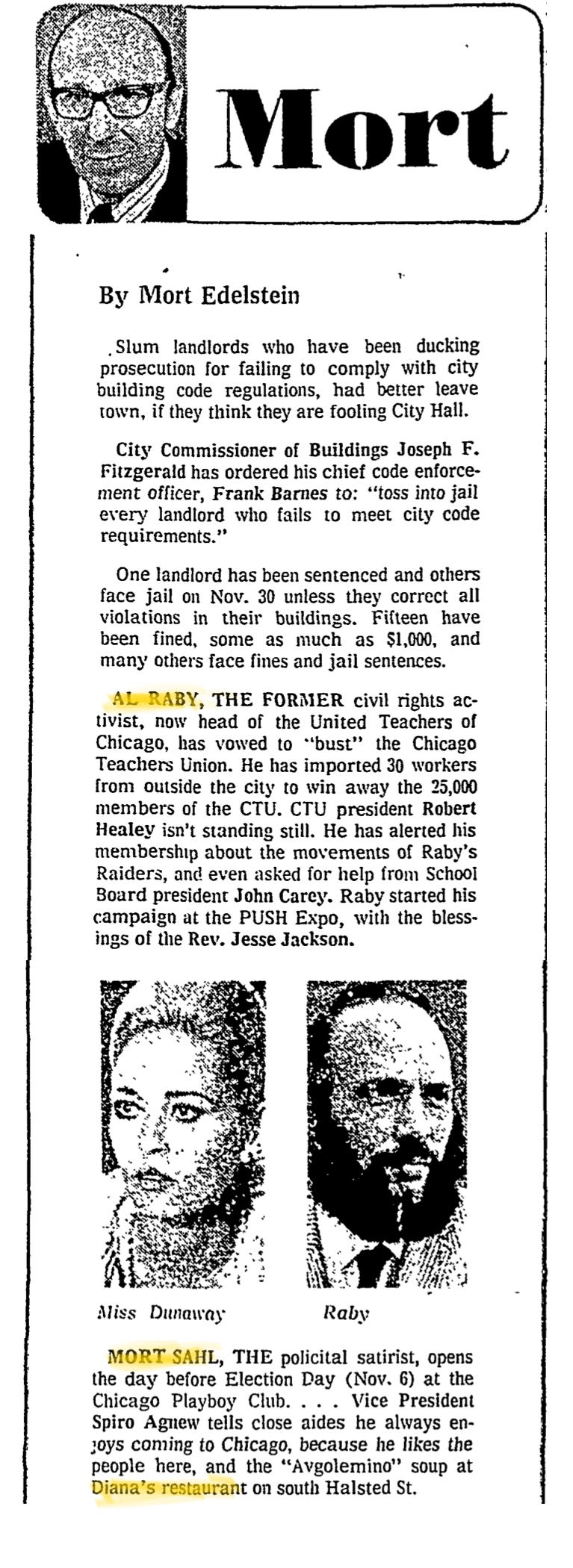

Mort Edelstein recently started a column that runs on the first page of the Daily News “Everyday” section, a mainly woman-oriented features section that’s surprisingly modern from a 2022 POV. They even pretend it’s not aimed at women, as if 1972 men are interested in things like how maternity homes are doing now that women have birth control and more abortion access—today’s main piece.

Mort seems to be a pal of Mike Royko’s, since per a 1973 Chicago Journalism Review bit of gossip, Royko interceded in a potential fistfight between the Sun-Times Tom Fitzpatrick and Mort—about something Mort wrote in this column. See the Feb. 19-20 weekend edition in Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today for more on that.

Mort’s column is a mix of reportage and gossip, as you’ll see below. Today he covers an interesting development in Chicago schools, in which prominent Chicago activist Al Raby now heads an alternative teacher’s union, hoping go elbow out the Chicago Teacher’s Union (CTU). We in 2022 know this is not going to happen.

Lower down, Mort Sahl will be playing the Playboy Club right before the 1972 face-off between Nixon and McGovern. Wouldn’t you love to hear that set?

And Mort includes a plug for the legendary Dianna’s in Greektown by having Vice President Spiro Agnew tout a traditional soup there. Now we know where Mort likes to hang out.

Dianna’s came up just last week when Cook County State’s Attorney Ed Hanrahan went straight there for lunch with his co-defendants and lawyers after they were acquitted of trying to obstruct the investigation into Hanrahan’s offices 1969 raid on a West Side Black Panther apartment that killed Fred Hampton and Mark Clark.

Don’t miss Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today

TUESDAY

October 31, 1972: The Mighty IC Disaster, Day 2

The Morning Papers

Monday morning’s crash between two Illinois Central commuter trains is officially “the worst in Chicago transit history,” reports the Tribune’s lead story, with 44 dead and over 350 injured.

“A train composed of the old, dusty green cars plowed into the rear of a train of new cars close to the 27th Street station, about three miles south of downtown Chicago,” writes Frank L. Spencer in the Defender’s main story. “The lead car of the old train ground into the new double decker, shredding it…like tinfoil. Bodies dangled in the wreckage of both. The dead and injured were concentrated in the lead car of the old train and the rear car of the other train, which was backing up at the moment of impact.”

In another Defender article, James M. Stephens writes that it was difficult to describe what the crash looked like:

“The rear of the first train, one of the newer aluminum models, was literally smashed like an accordion. The 7:15 train, the older model of the IC which had been in operation for years, had plowed through at least one-half of the last car of the earlier train. Metal was spewed over the tracks and blood was everywhere and on pieces of broken glass from the windows of the train.”

The Sun-Times main story notes that the first train was four new double-decker cars, while the second train “was composed of six 1926 model cars”. The Illinois Central went electric in 1926, per the Sun-Times, so the older cars are the original ones that started the IC’s electric service.

Back to the Trib: “The two trains were filled with nearly 1,000 passengers as the second train, traveling at a speed estimated by railroad and other investigators at 30 to 40 miles an hour, plunged into the backing train.

“The lead car of the second train veered to the right after striking and virtually demolishing the rear car of the first train. The car jumped up over the base frame of the first train’s rear car, splitting that coach in half. Most of the dead and those more seriously injured were in the rear coach of the front train.”

The Sun-Times’ Paul Galloway and Dennis Fisher tell it this way:

“The old train struck the new one in the rear as the new one backed up at the station…The first car of the old train rammed the last car of the new train, tearing it open like a giant crowbar ripping the length of a soft metal cylinder. It lifted the front train slightly, then crashed down the new car’s aisle for about 40 feet.

“The two cars fused into a twisted mass of metal, grotesquely festooned with bleeding bodies, train seats, and pieces of clothing and steel.”

The Trib also reports that “President Nixon sent John Volpe, secretary of transportation, to the crash scene, where he inspected the debris for 40 minutes and then interviewed victims at Mercy Hospital….At Mercy Hospital, Mrs. Frannie Peterson, 53, of 8123 S. Brandon Ave., told Volpe the new cars ‘are built like pie crust.’”

“Volpe…said the accident raised serious questions about the new light-weight steel and aluminum cars which commuter railroads have been buying for years.”

Investigations are under way by the NSTB, federal and state transportation departments, the Illinois Commerce Commission, and the Cook County coroner.

There doesn’t seem to be new information yet on the cause of the crash. The engineer of the second car, Robert Cavanaugh, survived but still couldn’t be questioned after spending five hours in the wreckage before being freed and rushed to the hospital. The Sun-Times reported one official said Cavanaugh was saved by the heavy metal door of the engineer’s compartment, though an unidentified man with him was killed instantly.

The Trib confirms that “The 27th Street station was a flag stop for the front (new double-decker) train, meaning it only would stop if someone wanted to get on or off.”

IC spokesman Jack Humbert still thinks the first train overshot the platform after being waved over by someone on the platform, then backed up to pick the customer up.

The Tribune explains the light signal system again: When the first, new double-decker train passed the 27th Street station, “a block signal at 31st would have turned yellow, with signals at 35th and 39th streets turning green.

“But when the first train backed up to the station…the light at 31st would have turned red, the one at 35th yellow, and the one at 39th would have remained green.”

But by the time the new double-decker train backed up to the 27th Street platform, turning the signal at 31st St. red, the oncoming second train of old single-decker cars had already passed 31st St. signal, and wouldn’t have seen it.

The IC says the engineer and conductor on the first train could communicate by radio—and we know from yesterday’s coverage that passengers heard the conductor giving instructions to the engineer over the intercom. But the old second train had no radio equipment at all, so “there was no contact between crews of the two trains.”

The IC says both trains were running on time, but passenger Isaac Johnson, 22, of 7337 S. South Shore Drive, tells the Trib that the first train was already nine minutes late when he boarded at 71st and Yates. Johnson thought the first train overshot the 27th Street platform and sat for about five minutes before backing up.

“As it moved into the station area, Johnson said, he saw the conductor, identified by the railroad as (Ernest R.) Cummings, jump out of the back coach and, after apparently looking at the other train approach, stood there on the platform and put his hands over his eyes.”

The Sun-Times reports that Michael Reese Hospital reported treating an Ernest Cummings, of 7808 S. South Shore Dr., for minor injuries. He was released.

“A block from the Reese emergency room, hundreds of relatives and friends of the passengers awaited word in the nurses’ buildings, which was set up as a temporary information center,” writes the Defender’s Robert McClory in another sidebar.

“With almost unbelievable organization, the hospital staff had responded to the situation. A mobile telephone truck had been set up outside. Coffee and sandwiches were available for those who felt like eating. Priests, ministers and hospital employees singled comfortingly with the crowd. Over the loudspeaker every few moments, a list of the names of patients and their condition was read.

“But in spite of the calm efficiency, there was untold agony for many. John Mills, 55, 7047 S. Constance, sat in a chair, tears streaming down his face. He hadn’t head a word from his wife, Agatha, since she left for work. He didn’t even know for sure if she was on one of the wrecked trains. But she hadn’t arrived for work, and she hadn’t called.

“‘No one there knows what happened to her,’ said Mills sadly. ‘I’m just hoping and praying.’”

I couldn’t find Agatha Mills’ name on the lists of dead or injured. However, as the Sun-Times notes, “It took more than 15 hours before the coroner’s office identified all the dead. Even then, the identification of one woman remained tentative.”

The Sun-Times’ Bruce Ingersoll reports from the morgue.

“Bodies are stacked up this high downstairs,” a “burly deputy coroner” tells Ingersoll, holding a hand shoulder high.

“The shelves in the refrigerated crypts in the morgue’s basement were rapidly filing up Monday as police squadrons and ambulances kept arriving.

“At noon there were nine squadrols parked bumper to bumper in a macabre line in front of the morgue, waiting their turn to back up to the unloading dock, Two squadrols, their rear doors flopped open, were already butting up against the dock. One was dripping blood that had oozed out of a canvas bag.”

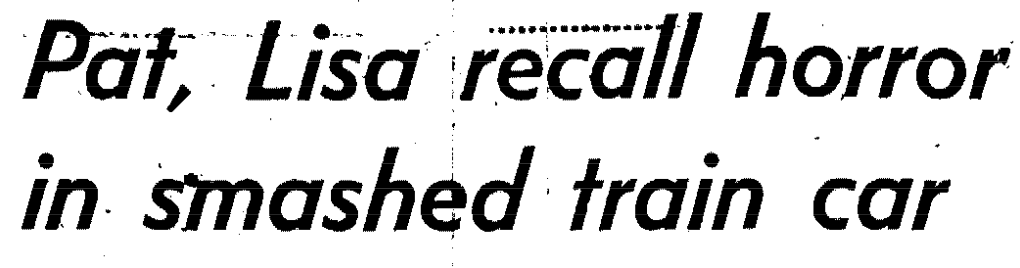

Sun-Times columnist Tom Fitzpatrick describes firefighter Billy Nolan following the sound of Patricia’s cries— “Please help us”—coming somewhere near the front of the mangled first car of the second train, which had slammed into the double-decker train at 27th Street.

Nolan finally finds Patricia Wysmierski and Lisa Tuttle, both 17 and pinned down side by side. They’d been sitting right behind the train engineer, in the very front of the car.

“‘Are you in pain?’ Nolan asked.

“‘I’m numb,’ Patricia said. ‘I can’t feel my legs.’

“‘Can you get us out?’ Lisa asked. ‘Are we going to live?’”

Billy Nolan reassures the girls—yes, they’ll be fine.

“When the car in which Patricia and Lisa sat telescoped itself into the modern Highlander, the impact of the crash flattened their seat,” writes Fitz. “Now they were pinned underneath the weight of the steel bulkhead of the motorman’s cab and the pressure from the pushed-in front end of the train.

“On either side of Patricia and Lisa were a middle-aged man and woman. They had died instantly. But the two girls didn't know that and no one ever told them.”

Fitz watches Nolan talk with his boss, Fire Captain John Wiendle. “Billy, you stay with these girls,” Wiendle tells Nolan, off to the side. “It’s gonna be a while before we can get them out. Stay with them, Billy. Keep talking to them. If you don’t, they’ll panic. If they go into shock, we’ll lose them for sure. Stay with them, Billy.”

Wiendle and Chief Deputy Fire Marshal Curtis Volkamer agree on a strategy for extracting the girls. “Curt, those two kids are wedged in pretty good,” says Wiendle. “We’re gonna have to be very careful with this job. We have the tools. We’ll lift the door off them just a little bit at a time. Then we’ll shore it up and move it up a few more inches.”

Wiendle goes back to Patricia and Lisa, and tells them the firemen will put an aluminum blanket over their heads.

“He told them that it was being done so they wouldn’t be burned or be overcome by fumes when the other firemen began using acetylene torches to cut the steel that was holding them captives,” writes Fitz.

“You won’t be alone,” Captain Wiendle tells Patricia and Lisa. “Billy Nolan here, is going to be under the blanket with you. I’m putting him there with you because he’s the gabbiest guy we have at our station and besides that he’s got seven kids of his own.”

Fire Department Dr. Joseph Carl gives the girls morphine injections for the pain, then Billy, Patricia and Lisa are under the blanket—for about six hours. Captain Wiendle tells the girls what noises they’ll hear, and keeps reassuring them. The girls need two more morphine injections as the hours drag on.

“Rescuers had two concerns,” Fitz explains. “If they lifted weight off and it fell back, the girls would be killed. If they lifted the weight off too quickly, that could kill the girls, too, because the weight of the train was now acting as a tourniquet on their injured legs.”

Patricia and Lisa will be the very last survivors freed from the train.

Monday morning, Lendale Pruitt went to his IC station at 75th and Exchange and got on his usual train, a special that ran express from 71st to 12th Street. He sat down in the second car from the front.

Pruitt, an Illinois Bell Telephone installer who worked in the Lasalle National Bank building, told the Defender’s Tony Griggs that the special he took always passed another another train at 27th Street.

“All of a sudden the ride started to get bumpy and the women started screaming,” said Pruitt, of 7541 S. Kingston. “We were going about 45 or 50 mph and the driver was unable to stop…”

After the tremendous jolt of the impact, Pruitt said the exit doors were jammed shut in the first two cars, but the passengers could move between cars. So, he said, “me and some other men went to the second car getting people off that were pinned in. We had to go through the first and second cars to get out (through the third car).”

“Recounting the ordeal from Michael Reese Hospital where he was being X-rayed for possible broken shoulder bones, Pruitt said, ‘Scores were injured and killed…I saw heads decapitated! I had to cry. I’ve never seen anything like that before—legs and feet cut off! Horrible! A lot of injured people were lying next to dead people. We helped off maybe 50 or more people. These were the same people that ride the same train all the time. I’m on it every day.’”

Prutt described how gradually police arrived to help first, then firemen about ten minutes later.

“Pruitt said he was on the train working side by side with the rescue team when he realized he had been injured in the shoulder. He left the crash and walked to Michael Reese Hospital.

“‘Most of the people who could walk walked over,’ he explained, ‘because there were a lot more people in a lot worse shape.’”

“‘This is a tragedy for the city—the city’s people are dead,’ said Mayor Daley.

“He was solemn and sad. He didn’t say much. But he watched closely for four hours as rescue teams probed and pried apart the twisted steel wreckage which had become coffin for many.

“One by one, bodies of the dead were carried past the mayor to waiting squadrons. His eyes moistened now and then. He would not say the thoughts that were running thru his mind.

“At one point there were gasps from the crowd as the bloodied body of a dead woman was lifted thru the top of the wreckage.

“‘Jesus,’ said the mayor softly. ‘God help us.’”

Hours later, after the last survivors are rescued from the mangled train—17-year-old friends Patricia Wysmierski and Lisa Tuttle—Mayor Daley goes inside the twisted cars for a tour.

“Standing on the station platform after the tour, the mayor, visibly shaken by what he saw inside, expressed deep regret for family and friends of those killed. He asked that the tragedy serve as a lesson in preventing further such disasters.”

The Afternoon Papers

The engineer of the first train in the disastrous IC crash tells Chicago Today that the brakes on the new doubledecker cars are faulty. That caused the crash, he says, because the bad brakes made him shoot past the 27th Street platform.

“Engineer James A. Watts, 51, a 24-year veteran with the I.C.,told Chicago Today in an exclusive interview that he overshot the 27th Street station yesterday because ‘the brakes didn’t work like they should.’”

When Watts backed the train up to line up with the platform and let a passenger off, the second older train coming from behind smashed into the new train.

“I’ve complained to my boss many times about the brakes on these new trains,” says Watts. “They are a little erratic. Sometimes they work fine. And sometimes they don’t.”

Today, we learn that the first train stopped at 27th Street for a passenger who requested to get off, not for a passenger on the platform who waved to get on.

Watts tells Today that his train was running about three or four minutes behind schedule, and traveling at 65 mph. The conductor pushed a button that signaled a passenger wanted off at the station.

But Watts says when he applied the brakes, they didn’t work right—and the train shot 320 feet beyond the platform.

Watts says he asked the conductor if he could back up. The conductor looked, saw no train coming, and gave the go ahead. IC officials confirm that this is a permissible maneuver. Watts says he wasn’t worried about a train coming from behind, because he thought the signals farther down the track would be red.

IC Vice President Jack Humbert repeats his message from yesterday—that when the first train backed up, the 31st signal would have turned red again, but the older train following had already passed by that signal when it was yellow, which only means to slow down.

Investigators will also look at the “head time” between the two trains. These trains run nine minutes apart as they leave the 71st and Stony Island station, but as the first train makes more local stops, the second train catches up. By the time the two trains normally get to 12th Street, they’re only two minutes apart.

Chicago Today’s Ronald Bergquist talks to engineer Watts and his wife in their south suburban home. Wilma Watts calls her husband very stable and safety conscious.

“She credits his temperate disposition to his war experiences during service for six years in the United States Navy.

“‘The railroad accident,’ she said, ‘recalled that terrible experience of returning from maneuvers on a destroyer to Pearl Harbor in 1941 and finding all that destruction and devastation.’”

Chicago Today’s lead columnist Jack Mabley—the most well known columnist in town behind Mike Royko—rushed to the IC crash scene and wrote a fervent piece for Monday’s paper. Today, he writes about the IC again:

“Perhaps I shouldn’t dwell on this, but I am incapable of writing on any other matter with the scenes on the I.C. tracks still burned into my mind,” writes Mabley.

“The hardened reporter who is unaffected by the physical suffering and the emotional tragedy of his job is a myth. The same is true of firemen and policemen. They go about their work at the scene of a tragedy, but they are tight-lipped, and sick inside.”

You’ll never get him sit in the last car of a train again, Mabley writes.

“The fragility of the new commuter cars was shockingly revealed in the wreckage.

“Pieces of metal were skimmed back along the right of way behind the wreckage. Many reports said it looked like a giant can opener had ripped open the last car of the front train. The thinness of the sides and roof fittings would make a can opener an appropriate tool.

“The old train which struck the new one was built like a tank, its weight and momentum crunched it into the packed commuter car like a knife going into a jar of peanutbutter.”

The chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board told a Chicago press conference that it’s “premature” to announce the cause of Monday’s IC disaster, but “the new rail cars did not measure up to the old cars in their ability to withstand impact, from the evidence on hand.”

“Daily News reporters during the Tuesday morning rush hour observed many IC commuters passing up the trains made up of the new Highliners and waiting for trains with the older cars.”

“I don’t have any idea if we can stay in business,” say Robert O’Brien, the IC’s director of press relations. “But let’s face it, an accident like this obviously doesn’t help any company.”

The IC was just about to get a $11.2 million federal-state grant to buy 15 more of the new double-decker cars, beyond the original 130-car order from the manufacturer. Now, says an Illinois Department of Transportation official, they’ll want to re-evaluate the safety of the new cars.

“A spokesman for the St. Louis Car Division of General Steel Industries,Inc., said that the new cars were made of high-strength, low-alloy steel, and built to the railroad’s specifications.”

If you came here from social media and have no idea what the heck this site is all about, here’s the place to find out:

October 31, 1972

Chicago Today: Flair pen ad

Flair pens came to market in the mid 1960s, but in 1972, they are still the cool, fun, almost subversive writing instrument of choice. A Flair pen is sort of a hybrid between an ink pen and a magic marker. Like magic markers, they come in many colors, not just blue, black or red. In its day, the Flair was revolutionary.

The nuns at Steve’s school, St. Anthony of Padua, didn’t allow Flair pens.

Note that the man in the suit, who is apparently the source of all the Flairs, is holding an iconic transistor radio of the early ‘70s—the round Panasonic transistor radio. This is a sign that the man in the suit is listening to rock music.

Here’s the Panasonic ball radio Steve got for Christmas in 1971, technically called a “Panapet” although I’ve yet to run into anyone who knows it by that name:

Wikipedia and other sources—which are perhaps working off Wikipedia, or vise versa —say that Panasonic issued the Panapet to honor the World Expo held in Osaka in 1970. The Parapet was only made through 1971-72. Online prices for a Panapet in 2022 range from about $30 to $129.

Here’s the Radio Geek on YouTube showing off his red Panapet:

October 31, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender: Letter to the editor

F.J.J. is a frequent Defender correspondent. Today, he or she is referring to the unprecedented October 15 press conference by Cook County Sheriff Richard Elrod and State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan, when the two officials announced the arrest of the De Mau Mau suspects. That kicked off days of breathless reporting among the major dailies that petered out by the weekend. It is true, as F.J.J. notes, that Malcom X President Dr. Charles G. Hurst is vigorously supporting President Nixon for re-election, and urging other Blacks to vote Republican too.

October 31, 1972

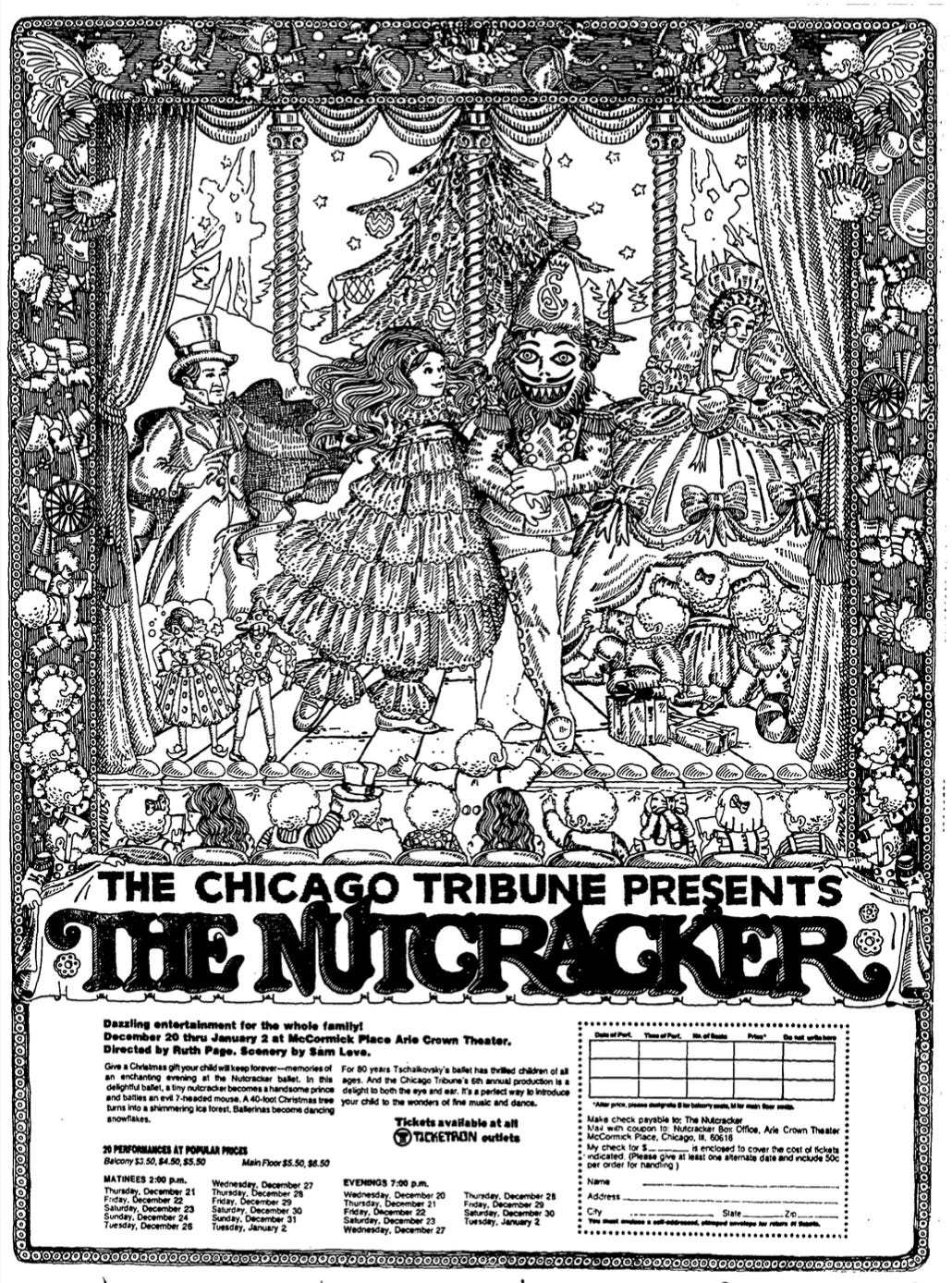

Chicago Tribune: Tribune’s 6th Annual Nutcracker

This Nutcracker preceded the Joffrey Ballet version at the Auditorium.

WEDNESDAY

November 1, 1972: The Mighty IC Disaster, Day 3

The Morning Papers

We have to start with IC spokesman Robert O’Brien’s interview with the Defender, because he seems to know less about the accident today, rather than more.

O’Brien won’t even state definitively that the first train overshot the 27th Street platform, and then backed up—despite unanimous agreement on this point by every single witness, including the engineer of the first train, who gave a long interview to Chicago Today yesterday.

Regarding whether the train overshot the platform and backed up, O’Brien says: “Apparently, and I have to say apparently, because this has not been borne out as of yet”.

There are two more crucial questions. For both, O’Brien’s answers read like a Monty Python sketch.

What happened with the train signals for the oncoming second train?

“There are signals there, and that question is a very complicated thing. I suspect that will be a very crucial part of the investigation.”

Are the new double-decker cars too weak? Why did the first train’s double-decker rear car sustain so much damage?

“I don’t know anything about the mechanics of a moving object and one that is standing still. It stands to reason that the old train had the momentum and that kind of force. If the circumstances had been reversed, it probably would have been the same thing.”

Yesterday O’Brien told the Daily News, “I don’t have any idea if we can stay in business….But let’s face it, an accident like this obviously doesn’t help any company.”

Today, O’Brien talks about himself in the third person to address that explosive statement:

“O’Brien also refuted rumors that the IC would be forced to go out of business. Citing a downtown newspaper for ‘misquoting an official and inaccurate headline writing,’ O’Brien said that the IC is ‘financially capable of handling situations like this. We will take things as they come.’”

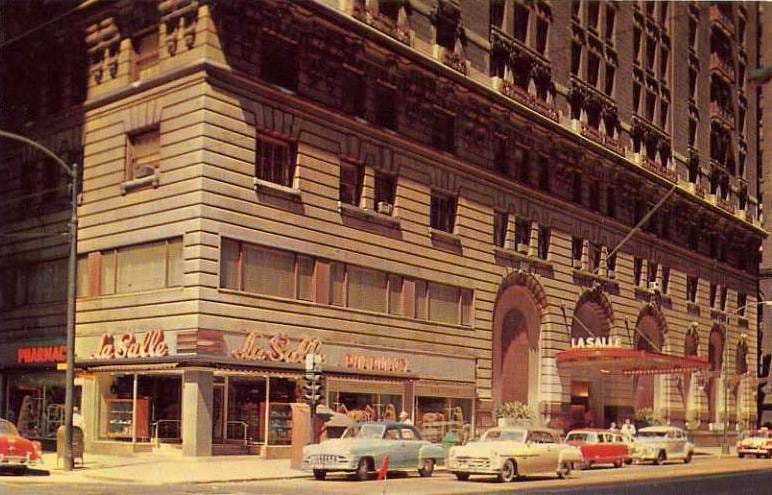

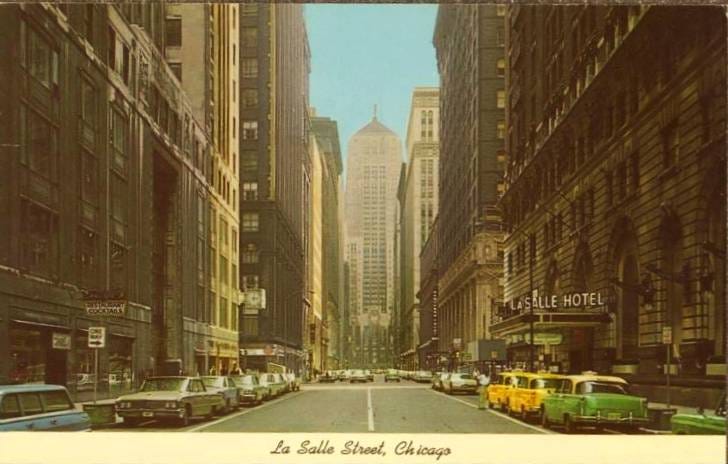

National Transportation Safety Board chairman John Reed, who toured the IC wreck himself on Monday, holds a press conference at the La Salle Hotel on Tuesday that forms the basis of the other main articles today. The death toll stays at 44 as of Tuesday, with 66 victims still hospitalized in ten area hospitals.

Reed says the NTSB investigation will be the main inquiry, with public hearings in Chicago within four weeks. But the federal investigators “had few answers Tuesday,” writes Joel Havemann on the Sun-Times front page.

“They said the IC’s new cars were unable to withstand the impact of the crash although they might be strong enough to meet federal standards.” And a thorough investigation will be necessary to answer why the first train backed up.

“The integrity and structural ability of the new equipment to withstand impact did not measure up with the old equipment,” the Sun-Times quotes Reed. “That was obvious.”

Indeed, as the stories all note, when the second train made up of six 1926-vintage single-deck cars crashed into the first train of four new double-decker cars, the second train’s front car sliced through half of the first train’s rear car.

“Reed said the old cars were more heavily and solidly built than the new ones, but he said specialists would have to determine whether the new cars provided inadequate protection,” per the Sun-Times.

The IC insists both old and new cars are made of steel—the new ones aren’t aluminum, as some people think. A vice president for the new cars’ manufacturer says they were “tested by being subjected to pressures of 800,000 pounds at each end,” and withstood that pressure. But he added, per the Sun-Times, “Obviously the pressure in Monday’s crash was greater.”

Reed wouldn’t comment on the interview by James Watts, the engineer in the first train, who told Chicago Today yesterday that he overshot the 27th Street platform and had to back up because the new cars have undependable brakes.

Also, none of the other papers name Chicago Today as the source of the Watts interview—per standard operating procedure in 1972. This morning’s Tribune includes a phone interview by reporter Stanley Ziemba with Watts’ wife, Wilma.

“‘He'd mention from time to time that the new cars were harder to stop than the older ones,’ said Mrs. Watts, trying to avoid tears,” writes Ziemba. “Until late Monday, neighbors visited the Watts home at 16044 S. Emerald Av. in Harvey, as the engineer watched re-creation of the tragedy on television.”

Mrs. Watts tells Ziemba that she and her husband aren’t sleeping well, because he’s “very conscientious.” Their neighbors tried late into the night to console Watts. “He’s no hot rodder,” says Wilma Watts.

At the La Salle Hotel press conference, Reed says it was conductor Ernest Cummings’ job to tell Watts whether it was safe to back up. As we read yesterday, Cummings jumped off the train before the crash. One witness said he saw Cummings standing on the platform, watching the oncoming second train, and covering his eyes.

The IC bought 130 of the new double-deckers, sometimes called “Highliners,” costing $40 million. Federal subsidies paid for 2/3 of that. Yesterday, we learned that Gov. Richard Ogilvie put a hold on a $11.2 million state grant for 15 more Highliners, until the safety is studied.

NSTB chairman Reed said if the new cars are found “very inadequate,” he would recommend for the Interstate Commerce Commission to ban them. “At this moment, I know of no reason to recommend cessation of carrying passengers by the IC,” the Sun-Times quotes Reed. “I hope we can find steps to cure the situation without shutting down the entire system. We could shut it down, but I do not foresee this.”

The Defender’s Robert McClory adds this information, amazingly skipped by the other morning papers: Reed “told newsmen that the IC had been warned to improve its safety precautions several times in the last few years because of serious accidents involving the railroad in Salem, Ill., Ashkum, Ill., and Glendale, Miss. But he said he didn’t know if the IC had implemented the recommendations of the safety board.”

Incredibly, as far as I can see, no morning papers mention that IC executives told the Trib’s Thomas Buck in February that when they ordered the new double-decker fleet in 1969, they “decided that no major overhaul work or other major repairs would be made to the old commuter cars. Instead of spending money to rebuild the old cars for 10 to 15 more years of operation, the Illinois Central officials specified that the cars be kept running on a safe basis at a minimum of maintenance expense.” Even Buck, author of today’s lead Trib cover story, doesn’t include this.

And nobody mentions either—again I’ll stipulate “as far as I can tell,” since it seems impossible—that in late March when the Illinois Commerce Commission approved the IC’s request for a 7% fare increase, the agency “ordered it to make immediate improvements in its equipment, maintenance, signal system and stations,” as the Daily News wrote at that time. The IC has been fighting that ICC order ever since.

Per the Defender’s McClory today, “Under questioning, Reed admitted that it is possible because of lawsuits and other legal problems that the full cause of the crash may never be made public.”

“Ironically, 15,000 of the nation’s top safety experts are in Chicago this week to attend the 60th annual conference and exposition of the National Safety Council,” McClory notes. “The conference opened Monday, the day of the wreck, and Reed addressed the delegates [Tuesday] about ‘railroad safety.’”

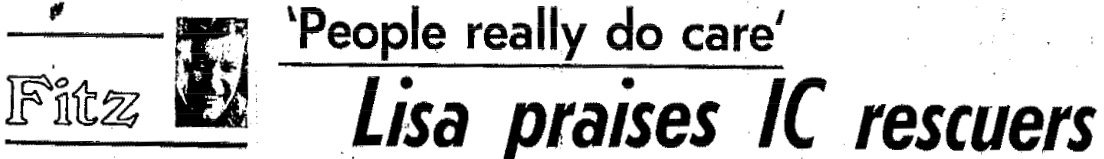

“Patricia Wysmierski and Lisa Tuttle, the last survivors extracted from the wreckage of the Illinois Central R.R. crash, were out of danger and cheered by visits from their families in Billings Hospital Tuesday,” writes the Sun-Times’ Paul McGrath on the front page.

Billings is the original name of the University of Chicago Hospital, where many victims were brought by helicopter on Monday.

The 17-year-old friends were trapped under heavy metal debris for six hours Monday as firemen used heavy equipment and torches to free them. Now, doctors are deciding whether they need more surgery on their crushed legs.

“Miss Tuttle, of 8413 S. Colfax, suffered fractures of both legs and of her collarbone, hospital officials said. Miss Wysmierski’s left ankle was crushed.”

The Billings spokesman says there is a danger that Wysmierski, of 8446 S. Green Bay, could lose her leg if infection sets in.

The girls’ friend Constantine (Dean) Lamperis, 18, of 8214 S. Exchange, sat nearby, and died in the crash…

…along with Pat Wysmierski’s neighbor, Linda Melendez, 21, of 8448 S. Green Bay.

“Miss Tuttle’s father, Robert Tuttle, 46, employed in the accounting department of the U.S. Steel Corp. South Works, 3426 E. 89th, remembered that when he dropped his daughter off at the train station Monday morning, she spotted Constantine.

“‘Lisa said, ‘O, there’s Dean. I’m going to talk to him,’ Tuttle recalled. ‘He often rode downtown with the girls.’”

“The friends were on their way to part-time jobs at Time Inc. The girls were seniors at Bowen High School and participated in a program in which they work in the morning and attend school in the afternoon.”

Mr. and Mrs. Tuttle didn’t know what had happened to Lisa when they arrived at Michael Reese Hospital. Like so many other families, they couldn’t find out where Lisa was.

“Then I heard two girls were still trapped in the wreckage,” Robert Tuttle tells the Sun-Times. “I had an eerie feeling—somehow I just knew one of the girls was Lisa. I turned to my wife and said, ‘That’s Lisa and Pat.’ Then we went out to the crash.”

Chicago Archdiocese Cardinal John Cody—or as they say in the papers, “John Cardinal Cody”—offers a “concelebrated” mass for IC victims at noon in Holy Name Cathedral.

“Veteran Illinois Central Railroad trainmen blamed the lack of emergency procedures and faulty brake systems on new equipment as contributing causes of Monday’s crash which claimed 44 live and scores of injuries,” the Trib’s James Strong reports.

Strong talks to M. Stuckey, general chairman of the I.C. committee of the United Transportion Union, AFL-CIO. Stuckey says brakes may or may not have been the issue on Monday, “but we have had 200 overshooting in the last year and on a short run I make from Richton Park, we’ll overshoot at least five stations,” he says.

Stuckey says the IC is the only Chicago commuter line that doesn’t have emergency signal equipment on the trains. Also, the IC stopped including a flagman as a third crew member to warn oncoming trains of unscheduled stops.

“We don’t care to go into that,” says an IC spokesman.

Stuckey say the crew size was the issue in 1969 when the union struck for a week, insisting the IC add a flagman as a third crew member. Stuckey says the union got the third crew member, “But to prove they weren’t needed they would not allow the crewman to flag oncoming trains at unscheduled stops and gave them conductors or collectors duties.”

The Afternoon Papers

Still just two afternoon papers, but we see two editions of Chicago Today.

A lot can happen in the course of a day.

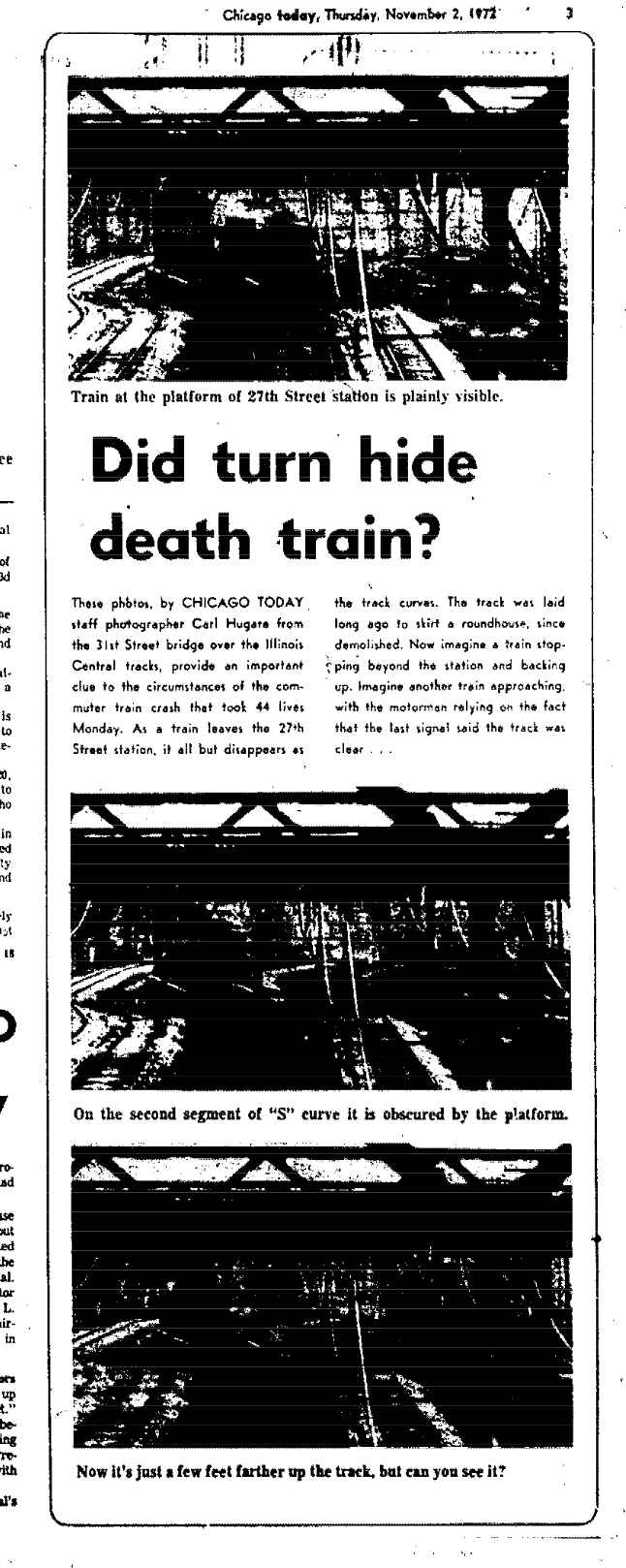

We better start with “Was death train hidden?”

Unfortunately, the microfilm for Chicago Today seldom reproduces well, even digitally. Though you won’t be able to decipher the pictures, the captions on this repeat on page 3 tell the story.

“An apparent violation of railroad safety rules may have led to the collision of two Illinois Central Railroad commuter trains that killed 44 riders and injured more than 300 persons, railroad officials said today.

“Jack C. Humbert, I.C. Vice President in charge of operations, confirmed reports received by CHICAGO TODAY that a flagman was not used to protect the first train as it backed up to the 27th Street platform.

“Conceeding this was a violation of the line’s rule, Humbert said when a train leaves one block and enters another it ‘can’t back up unless a flagman protects the rear of the train.’

“A block is a section of track protected by signals and designated to prevent the type of collision that occurred Monday.” In this case, the block signals we’ve been hearing about were at 31st, 35th and 39th Streets.

The flagman is required to walk “a sufficient distance” behind the stopped train and place two “torpedoes” on the tracks—devices that go off if a following train runs them over, a warning the engineer to stop.

But on Monday, conductor Ernest Cummings either stood on the 27th Street platform and looked south, or looked from the train, depending on which account you go with.

Chicago Today now reconstructs the events with current knowledge:

Train #1 approached 27th Street at 65 mph, and conductor Cummings pressed the buzzer alerting engineer James Watts that a passenger wanted to get off, because 27th Street is a “flag stop.”

Watts already told Chicago Today in an exclusive interview that the new double-decker cars have unreliable brakes, and when he tried to stop on Monday, the train overshot the platform by about 320 feet.

“That meant the train also would have passed a block signal about 100 feet north of the platform. This caused the signal at 31st Street to change from red to yellow. The yellow signal indicated that no train occupied the tracks thru 27th street and a following train could proceed at reduced speed.”

Though Today leaves this out, we’ve also read that passengers heard conductor Cummings give Watts the go ahead to back up to the platform. When the train backed up, the block signal at 31st Street would have changed back to red—but train #2 had already passed that signal, and wouldn’t have seen it.

Now we hear yet another version of conductor Ernest Cummings’ actions after train #1 overshot the platform, this time from passenger Theodore E. Williams, 44, of 7803 S. Bennett Avenue, an adjuster for the Social Security Administration.

“The conductor plugged his microphone into the wall, opened the door facing west and hung out of the door while the train backed up for about one minute, Williams said.

“Williams said the conductor never went to the back of the car, but rather opened the door in the middle of the last car, about 40 feet from the end of the highliner.

“As the train rolled into the station, the conductor told the engineer ‘Hold it,’ but then it looked like the engineer picked up more speed and the conductor said ‘Stop…stop…stop,” Williams tells Today.

Williams says Cummings sounded “desperate” at that point.

“The conductor was jumping and trying to hold up his hand to warn someone to stop.”

Reporters Morris and Marks inspected the 27th Street platform views and determined “because of the curvature of the platform, it would have been difficult for the conductor to see an on-coming train….[T]he platform and shelter obstruct the view of any train on track three at the station or to the immediate north.

“Also, the rear of the Highlanders are painted black which causes the train to blend in with the black and grey color of tracked railroad structures, right of way and the buildings to the north.”

Finally: “The stage for Monday’s disaster was apparently set when both trains were routed on track three—the northbound local track. An I.C. tower man, who asked not to be identified, said express trains such as 720 normally are routed on track four, and locals like 416 are kept on track three.

“Efforts by investigators to learn all of the details of the accident were hampered yesterday when conductor Cummings refused to talk with I.C. officials.”

Open Letter from the IC to Chicago

This full-page or almost full-page ad starts running in the late editions today and will appear in all the papers by tomorrow.

The letter is signed by IC President Alan S. Boyd. He’s the subject of a strange, disjointed and incredibly long interview in the March 26 Tribune. Rather than discuss the IC’s challenging year of delays and disrailments, which had already stranded IC passengers for hours and made up to 12,000 people late for work on several occasions, Buck talked about the railroad industry in general.

The Boyd interview followed up the even stranger February 21 Tribune article in which nine IC executives told Trib reporter Thomas Buck that they felt badly that 1972 was the worst winter of service in the entire 116-year history of the IC—but then admitted that when the IC ordered replacements for their current ancient fleet in 1969, the company “decided that no major overhaul work or other major repairs would be made to the old commuter cars. Instead of spending money to rebuild the old cars for 10 to 15 more years of operation, the Illinois Central officials specified that the cars be kept running on a safe basis at a minimum of maintenance expense.”

But again, IC President Alan Boyd didn’t address that in his lengthy March interview.

During the six hours when 17-year-old friends Lisa Tuttle and Patricia Wysmierski were trapped beneath mangled metal as firemen used heavy equipment and acetylene torches to free them, each girl told the rescuers to help the other one first.

“Lisa kept saying, ‘I’m OK, take Pat. She’s hurt worse than I am.’ And Pat kept saying, ‘Take Lisa. I’m O.K.,’” Dr. Peter Rosen of Billings Hospital tells Today’s Pat Krochmal.

“Even here in the emergency room, Lisa was asking how Pat was while she was getting treatment in another room. Then someone supposedly tried to treat Pat and she yelled. Then Lisa leaned back and said, ‘I heard her voice, she’s still O.K.’”

Rosen decribes an even more chilling picture of the accident scene than we’ve read so far:

“The girls were surrounded by bodies….Pat was pinned under Lisa, and there was a dead woman under her.”

We also hear more about Sue Milano, 23, of 11115 S. Avenue M, the woman we first met hanging upside down. Milano was trapped for five hours. Dr. Rosen:

“She’d say, ‘I’ll be OK. Just get me out of here so I can go to bed.’ She didn’t complain. She never lost hope. She never whined. No one did. They knew people were working as hard as they could….One fireman lay under the train the whole time with Sue, holding her head. All we could get to was one hand and her face. The air tanks from the car, which I think had something to do with the brakes, was covering her from the pelvis up.

“When we removed the pressure from the tank, she fell apart fast. People were in profound shock. When the metal pinning them was removed, they’d start to hemorrhage. Sue took an unbelievable number of transfusion. Maybe 25.”

Sue Milano remains in critical condition with a fractured pelvis, ruptured bladder and liver, and a broken leg.”

November 1, 1972

Chicago Today

Spring and summer, Chicago papers send a photographer to Lake Michigan for cheesecake pictures, using the weather as a news peg: “Look, it’s hot in August and young women are wearing bathing suits at Oak Street Beach!”

Fall and winter, Chicago papers run bikini pictures from Australia via the AP or UPI, and don’t even really try to make up a news peg.

November 1, 1972

Chicago Today: A car with its own Levi’s

November 1, 1972

Chicago Today: Reader’s Digest ad

Must men die younger? It’s a good question, Reader’s Digest—tip of the hat.

In researching Steve’s life, I remember talking to one of his clients, who was probably about 40 in 1972. Just reminiscing about his life, he mentioned off-handed that he’d never expected to live into his 80s. I stopped him, and asked why. The answer: In his childhood and youth, it was just normal for men to drop dead in their 60s.

And that makes sense when you look at the CDC’s chart of expected life expectancy. American men born in 1900—this man’s parent’s generation—had a life expectancy at birth of only 46.3 years on average, which went up to 65.6 years for men born in 1950. Steve’s client was born around 1930, so his “average” life expectancy at birth would have been somewhere in between, presumably. Those averages skew so low due to higher infant mortality and, for anyone living before World War II, the lack of any antibiotics. But still. When you think about it, adults in mid-20th century America were emerging from an almost Dickensian youth.

November 1, 1972

Chicago Daily Defender

The church is an unassuming building that you may not have noticed driving by, unless you live in the area and know it more intimately, but it still stands in 2022, and looking quite new.

November 1, 1972

Chicago Today: Yet another FM rock station, WMAQ

THURSDAY

November 2, 1972: The Mighty IC Disaster, Day 4

The Morning Papers

Already, the all-consuming tragedy of mass death on the lake at 27th Street begins to fade. This is life. This is, accordingly, the news. One friend of mine who was an adult in 1972 still remembers driving by on Lake Shore Drive and seeing the mangled hulk of steel from Monday’s crash—already shoved to the side so Tuesday’s commute wouldn’t be impacted.

And so the devastating crash of an older IC train into a newer, lighter train, killing 44 people and injuring hundreds, has left the Defender’s front page by day four. In the Sun-Times, the IC disaster falls below the expected 1973 Chicago budget reaching $1 billion for the first time. That’s $6.75 billion in 2022 dollars. The actual Chicago budget in 2022 is/was $16.7 billion, and it wasn’t big news.

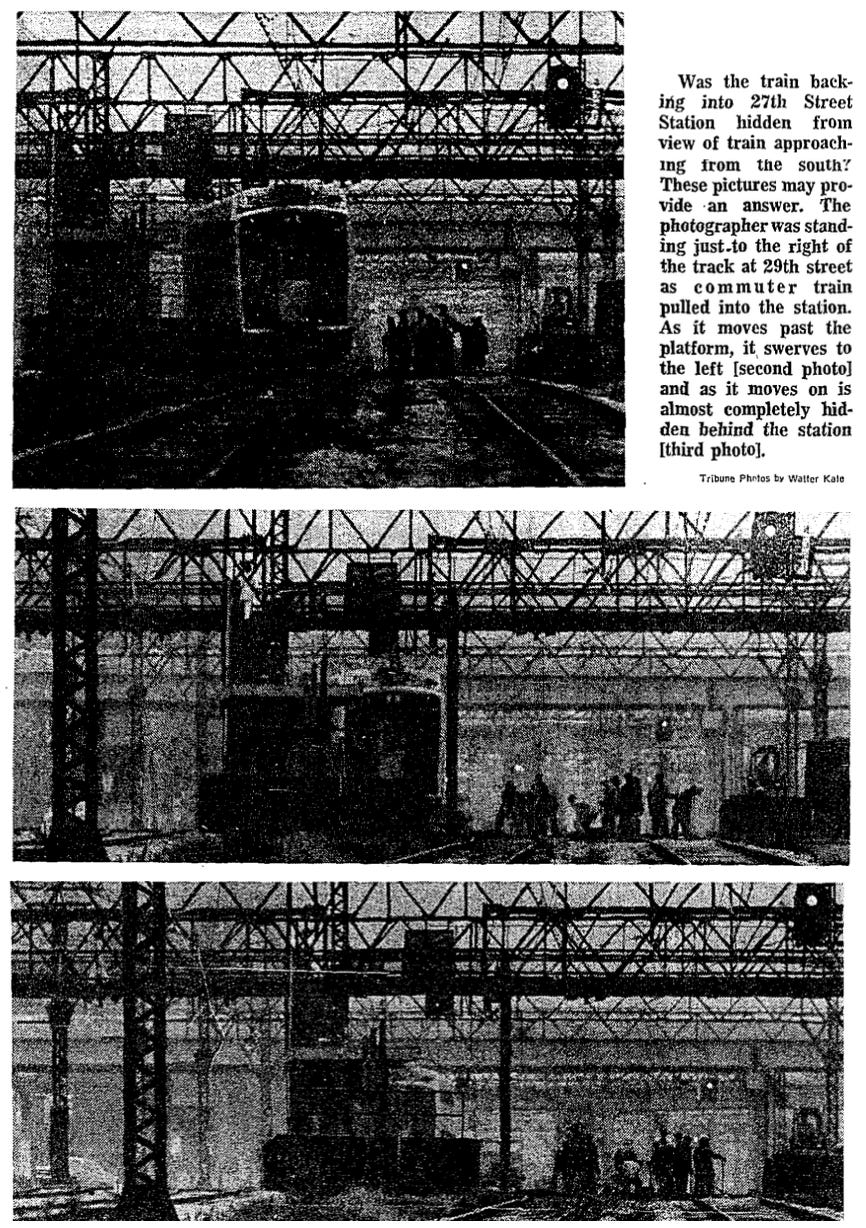

The Sun-Times and Tribune feature the same basic pictures on their cover as Chicago Today did yesterday, showing the curvature of the IC tracks that could hide a train at the 27th Street platform from an oncoming train. Luckily, the Tribune photos reproduce well enough to get an idea of what everybody’s talking about:

The Sun-Times and Tribune go over the current theory of the crash laid out in yesterday’s afternoon papers, but with an interesting extra emphasis on one point, and a surprising new twist. We’ll go with the more detailed Trib version.

First, the signals: As we’ve read before, the first train must have tripped the block signals further down the track when it overshot the 27th Street platform. Those block signals would have indicated further south at 31st Street that train #1 had left the 27th Street station. When train #1 one next backed up into the station, it would have re-activated the block signals to give oncoming trains a red light at 31st—but train #2 would have passed 31st Street already.

Perhaps worse, when train #1 backed up over the block signals, that action would have turned the signal just north of the 27th Street platform green. Since train #2 had past 31st Street, the engineer would have been looking at the next signal, at 27th Street—and seeing green. So he may have even sped up.

Second, the visual issue shown in the pictures above: The Tribune calls this “a significant factor,” writing that “the general visibility” was “impaired by overhead structures and supporting columns in the area. Further, as [train #1] backed toward the station, [second train engineer Robert] Cavanaugh’s view of it was largely obscured by the station itself. The track curves to the west along the station platform. The train would not have been in full view of Cavanaugh until the rear car was alongside the platform.

“The confirmation of this ‘hypothesis’ apparently lies with Cavanaugh, who suffered multiple fractures in the accident and remains in serious condition in Billings Hospital.”

And the Tribune buries this nugget at the end of its long article: The design of two crucial posts at the end of the new double-decker cars is “highly suspect in design.”

“These are vertical metal posts which extend up from the strong base structure of the car and form major supports of the superstructure. The strength of the end posts in the accident is of importance because the front car of [train #2] went over the base structure [of train #1’s rear car] to cut thru much of [train #1’s rear car].”

And the NTSB and Federal Railroad Administration already knew this is a problem. In 1969, a similar accident happened in a smaller collision in Darien, Connecticut, NTSB chairman John Reed told reporters at the La Salle Hotel. The NTSB recommended that the FRA should test the crash worthiness of the new cars.

“As a result, the FRA asked Congress for a $100,000 appropriation for the study, but this was rejected. Using other funds, the Department of Transportation has begun such tests at its railroad testing center at Pueblo, Colo., with a view to recommending improved standards.”

This is mind-boggling news that, if you ask me, should have been a front page headline.

Monday’s crash took place on track 3. A split second before train #2 plowed into the back train #1, an express train from Flossmoor sped by on adjoining track 4, going 60 mph since it was nonstop between 53rd Street and Roosevelt Road.

During the crash, the “force of the impact sent the lead car of [train #2] careening across track 4 where [train #3] had just passed.”

“‘If the Flossmoor train had been slightly later who knows how many more lives would have been lost,’ said David H. Strong, chairman of the Illinois Commerce Commission.

Train #3 was so close to the deadly crash, flying debris damaged the last car. Passengers told the conductor “they heard a ‘clunk.’ When the conductor inspected the train at the Roosevelt Road station, he found two handrails were damaged and paint scraped from the last car.”

Psychic Joseph DeLouise, “a much sought after personality in the field of extra sensory perception,” predicted a South Side train crash, on the June 27th edition of Wesley South’s WVON radio talk show, “Hot Line.”

A woman contacted the Defender about the prediction, writes Tony Griggs, and Wesley South was able to find tape of the interview. The exact prediction:

“I feel very soon—when I say soon I mean anywhere from six months to tomorrow—I feel that there will be a train crash on the Southside of Chicago in the very foreseeable future, very soon.

“Over 30 to 37 people will be killed. But when I receive the numbers I really don’t know if it refers to people or something else. I see a train being derailed. This is an exclusive prediction.”

Speaking to Griggs, DeLouise says he knew the crash would happen on the IC, “but declined to indicate that to the listeners for fear that panic would follow.”

“I thank god when I’m a little off on my predictions,” DeLouise tells Griggs. “Just think, if I predicted the exact number of 44 dead and the exact spot where the crash would take place that would dangerous. I could go crazy and people would be afraid to live their lives.”

“Tears as mournful as the drizzling rain fell inside three south side funeral chapels last night when hundreds of persons consoled the families of victims killed in Monday’s tragic train crash,” writes the Trib’s Rick Soll.

“As the mourners crowded into the hallways of the chapel at 2939 E. 95th St., very few words were spoken. Mourners walked by five rooms containing five closed coffins, covering their eye and moving their lips in silent prayer.”

Five parishioners of Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church, 3208 E. 91st Street, were killed. “We all know each other here,” Father James Mahoney tells Soll. “And what can I tell them to make their grief easier to bear? I tell them this, that the only way to continue loving the ones they’ve lost is by continuing to love the ones still on earth even more.”

Last, the Sun-Times offers this article, which is brief but a real doozy, especially if you’re IC President Alan Boyd:

Glenwood resident and IC passenger Michael S. Froman of 510 Pleasant Dr. wrote an irate letter to IC President Alan Boyd, and Boyd wrote back on Feb. 17.

“In the letter, Boyd…said the IC was having ‘an increasing number of failures in electrical power supply’ and ‘problems with portions of the track.’ He descried the signaling system as ‘so old now that it consists of patches upon patches,’ and told Froman he was ‘bitterly disappointed at our inability to provide continuing high-level satisfactory service.’”

Boyd’s only comment to the press Wednesday came as a written statement that he has instructed all IC employees to only speak with investigating agencies, to “avoid confusion.”

Meanwhile, NTSB chairman John Reed held another press conference at the La Salle Hotel—perhaps he’s staying there during the 60th annual conference and exposition of the National Safety Council which is, ironically as the Defender’s Robert McClory pointed out, meeting in Chicago this week.

Reed did say that a preliminary investigation shows no malfunctioning in the IC’s signal system, but he added, “We have not eliminated the possibility of a malfunctioning of equipment.”

The Afternoon Papers

“The doctors were ripping our shirts to give us pain shots. We asked to be given something to put us to sleep so we wouldn’t know what was going on. But they said no, they’d have to know how we were doing.”

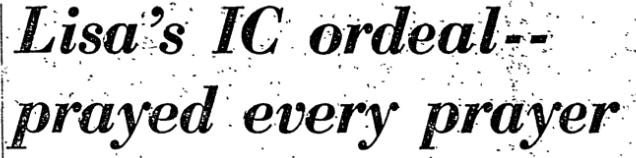

Pat Krochmal leads her front page story on Lisa Tuttle and Patricia Wysmierski with Lisa’s recollection. As you can see below, Lisa met with reporters in her hospital bed, with her legs traction. Both her ankles were fractured and dislocated, and another unspecified bone was also fractured. Pat has a broken thigh bone, a fractured ankle and torn knee ligaments. She did not participate in the press conference.

Lisa and Pat, both 17-year-old seniors at Bowen High School, were trapped underneath steel for six hours as firemen worked to cut them out. “The story of their courage…moved thousands off persons in Chicago and throughout the nation,” write James Kloss and Edmund J. Rooney in the Daily News.

“The flame throwers were the worst thing,” said Lisa, meaning acetylene torches used to cut through the metal.

“Fireman William Nolan stayed with the girls during most of the time they were pinned in the wreckage,” writes Krochmal. “‘He was absolutely fantastic,’ Lisa said. ‘He kept telling us they’d get us back to work in time for the coffee break. He kept asking us about our classes and he really tried to keep our minds off what was going on. At the time, we wanted mostly to get the pressure off our legs.’”

“I prayed every prayer I could think of,” the News quotes Lisa. “Then, she recalled seeing a sign hanging over her head,” writes Krochmal. “It read ‘God is the Answer’ or ‘God will See You,’ she couldn’t remember exactly.”

“We thought about other people a lot,” said Lisa. “We thought about our families. We weren’t that concerned about ourselves.”

“Her blue eyes flashing and almost jubilant, Lisa told reporters she was ‘looking forward to having her casts autographed.’”

Illinois Commerce Commission chairman David H. Armstrong signed an order prohibiting commuter trains from backing across block signals the way train #1 did just before Monday’s deadly IC crash.

“Most railroads already have regulations that prohibit backing across block signals in certain cases, he said. Some allow the backing if a flagman walks before the train to warn following trains, he said.”

Even backing over block signals with a flagman will be prohibited until the crash investigation is complete.