The Shoreland: Life, Death, Tragedy and Money at "The World's Finest Residential Hotel"

Chicago History Rabbit Hole

To access all website contents, click HERE.

Welcome to Chicago History Rabbit Hole! Regular readers know that when we dive into a lengthy digression following some interesting tidbit within a post, the Chicago History Rabbit appears as a heading. You’ll find some new rabbit hole discoveries in this section, and I’ll also gradually gather the many existing rabbit holes elsewhere on the site right here, so they can burrow together in one place.

New Year’s Eve 1937 in the Loop was off the hook.

“State street was a bedlam from Lake street to Van Buren,” the ground covered in confetti, exulted the Tribune’s front page story. Partying was back baby after the worst of the Great Depression.

The reason was simple, the Trib explained: “Better business, better spirits, no prohibition.”

Randolph between State and Clark was “a solid mass of shouting and laughing humanity…It was impossible to escape the crush. One could not walk a block in less than 15 minutes.”

A long line of tipsy strangers, now best friends, did a snake dance at Randolph and State. The jammed Palmer House charged $25 a couple in the Empire Room—about $550 in 2023 money.

Mike Fritzel claimed that his celebrity-magnet restaurant at State and Lake ran out of 50 cases of wine and had to go find more.

Unfortunately for Dr. Leopold S. Gumberts of the Shoreland Hotel, he’d wandered east off gay State Street onto Monroe, ambling toward Wabash.

Dr. Gumberts was walking down the sidewalk you see above—in 2022 via Google Streetview (left), and in 1960ish via a postcard from John Chuckman’s Photos on Wordpress (right). He strolled along with all the same buildings looming over him, surrounded by happy New Year’s Eve partiers. Was he heading for the Palmer House to meet wife Sadie and perhaps son William at the Empire Room?

Dr. Gumberts could probably afford the Empire Room’s steep New Year’s Eve charge. According to the 1940 census, his Shoreland digs cost $170 per month—about $4,000 in 2023 money—and remember the country was just coming out of the Depression. Or did Dr. Gumberts leave Sadie and William home at the Shoreland? Either way—

—a tall man and a shorter guy stopped Dr. Gumberts, 72, on the sidewalk. The scene on Monroe was as wild as State Street. As their conversation progressed, nobody noticed the elderly physician raise both hands high over his head.

Dr. Gumberts was getting robbed. The short guy pointed a gun at the good doctor.

“This is New Year’s Eve,” Dr. Gumberts protested. “Don’t you fellows ever take a holiday?”

According to the Tribune, “The bandits shook their heads. They took, instead, his diamond ring valued at $600 and $6 in cash.”

That’s a $13,000 ring and about $130 cash in 2023 money. See? Dr. Gumberts could afford the Empire Room.

You have to love how cavalier the Tribune was about a venerable doctor getting held up at gunpoint in the Loop, possibly right in front of the uber high class Palmer House:

Dr. Gumberts should have stayed home. According to the Tribune, the Shoreland Hotel was overflowing for New Year’s Eve, no doubt with a big band swinging in its Crystal Ballroom.

Which brings us to the Chicago History Rabbit, blinking at you from the top of this post in front of the gorgeous Shoreland—55th and the lake, as its address was called back in the day. More specifically, 5454 S. Shore Drive. I’ll repeat the postcard so you don’t have to scroll back up.

The view is a fantasy 1920s view imagining Daniel Burnham’s completed vision for the south lakefront, with protected lagoons all the way downtown and no racing bikers or electric scooters terrorizing pedestrians on the lakefront trail.

Just kidding! There would have been plenty of bikes already, just no bike shorts.

On our way down the Shoreland rabbit hole, we’ll look at the hotel’s history and architecture, plus a slew of recent pictures. And of course we’ll meet people like Dr. Gumberts who made the brick-and-terra cotta Shoreland a living, breathing part of Chicago.

Heck, the Shoreland’s permanent residents connected the hotel to every major event in the city’s history, sometimes just by being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Shorelander Eliza Wilhartz survived both the great Chicago Fire in 1871 and the 1903 Iroquois Theater fire, still officially the fifth worst in U.S. history with 602 dead. (See the “Who the #$@!% is Eddie Foy” Chicago History Rabbit Hole for the Iroquois Theater disaster.)

We’ll weave some Shorelanders into this post while covering the building itself, saving celebrities and more resident stories for another post. Heads up, several of the famous people always mentioned in connection with the Shoreland were almost certainly never there. Everybody loves a rumor, especially repeating them.

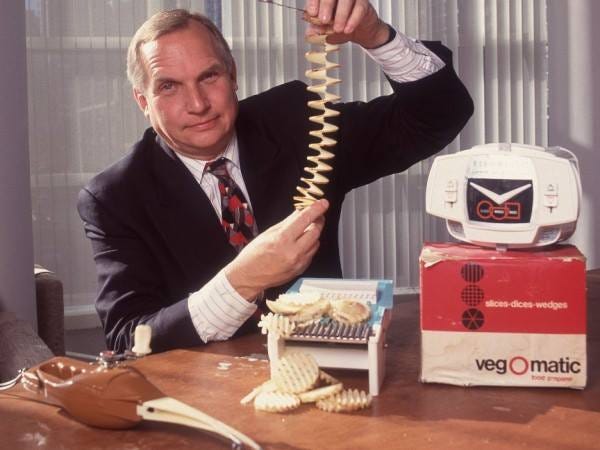

For instance—no Elvis! However, several far more interesting people were at the Shoreland. At least three Shoreland visitors literally changed the course of 20th century history, one of whom made two speeches at the hotel. One semi-permanent guest became the most repeated meme in American pop culture before the internet.

Some unknown Shorelanders are also better than an imaginary Elvis visit, including a couple of tasty cab driver stories about Shoreland fares. Subscribe for free below to get that coming post straight to your emailbox.

We won’t hear much about the hundreds of workers who toiled at the Shoreland. They’re usually out of sight, changing beds and carrying bags. So let’s give them a shout-out now—including my Gramma. She was a maid at the Shoreland and several other Hyde Park apartment hotels during the Depression. Here she is posing on a day off, coolly showing some leg beneath what is either a fake or borrowed fur. She’s enjoying some winter sun in front of the Windermere Hotel, where she also worked, at the northwest corner of Jackson Park. The fountain is no longer here, and alas, neither is Gramma.

Chicago’s Residential Apartment Craze

First off, what is a huge luxury hotel like the Shoreland doing in a regular old South Side neighborhood? Just minding its own business, these days.

No double decker tour buses cruise by the Shoreland. Tourists don’t stumble across it on their way to a Wendella boat ride. To know the Shoreland you must seek it out, or live nearby.

The Shoreland rose in Hyde Park because this is not your typical neighborhood. Hyde Park began as a bucolic bedroom community far from the madding crowds of Chicago, planned by New York lawyer Paul Cornell after he bought up 300 acres in 1853 between what is now 51st and 55th Streets. Cornell shrewdly gave 60 acres to the Illinois Central railroad “in exchange for a train station and the promise of 12 stops daily” downtown, according to the book “Hyde Park Illinois” by Max Grinnell.

Between 47th and 56th Streets, the IC—today known as the Metra Electric—runs from one to three blocks west of DuSable Lake Shore Drive, dividing East Hyde Park from the rest of the neighborhood and creating a (very) rough right triangle of buildings. The pointy northern tip is at 47th Street, the wide base at 56th. The Shoreland rises near 55th St. on the hypotenuse of Lake Michigan.

Hyde Park grew first as a middle and upper middle class suburb, and later as home also to workers and visitors for the 1893 Columbian Exposition world’s fair in nearby Jackson Park. Simultaneously, a little thing called the University of Chicago started up.

Hyde Park’s lakefront remained an attractive get-away from downtown Chicago at the turn of the 20th century. According to Grinnell’s neighborhood history, over 100 hotels were built in East Hyde Park in the first two decades of the century. That sounds a tad high to me for just the eastern part of the neighborhood, but why quibble.

Let’s just say there were a lot of hotels, nearly all part of the residential hotel craze—including the Shoreland.

“The apartment hotel was an unusual 1910s-1920s phenomenon,” Chicago Cultural Historian emeritus Tim Samuelson explains. “You could stay there as a regular hotel, but a considerable percentage of the occupants were permanent residents who wanted hotel amenities like laundry, room service and a convenient place to eat.”

People “only recently have been realizing the sleeping beauty of Chicago’s wealth of 1920s apartment/hotels,” says Samuelson.

Apartment hotels sprang up across the city due to Chicago’s explosive growth after the Great Fire of 1871, which brought higher land values and housing prices. Can’t afford a house in your favorite neighborhood? Get in line. By the late 19th century, many middle class, upper middle-class, and even wealthy Chicagoans found single family homes in their favored areas more expensive or trouble than they were worth. Snooty polite society began accepting apartments as suitable dwellings. The apartment hotel, with its many services and attractions, was better still. The Shoreland and its fanciest brethren were the logical pinnacle of the trend.

Apartment hotels of varying socioeconomic levels mushroomed across Chicago in the first decades of the 20th century. The smaller, low-end examples were basically the bed-and-breakfasts or SROs of the time. The luxury versions popped up mainly near the lakefront. Besides Hyde Park, when you walk around places like Edgewater, Uptown, Lincoln Park, Lakeview, and South Shore, the most impressive terra cotta-ornamented apartment buildings you’ll see were originally apartment hotels.

East Hyde Park still has loads of surviving small apartment hotels, a few big ones, and five very large specimens, all now apartments or condos. That includes the Windermere on 56th Street at the northwest corner of Jackson Park, seen earlier peeking out from behind my Gramma…

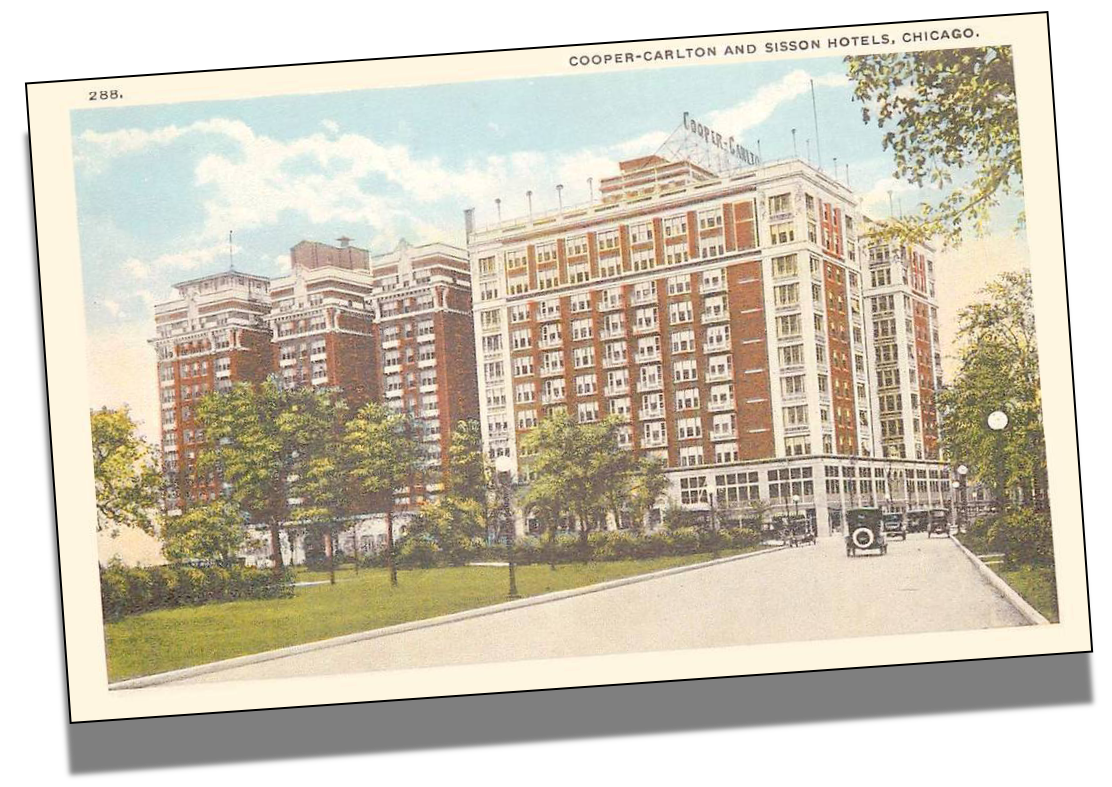

…and at 53rd Street and the lake, the former Sisson Hotel (left), where Mayor Harold Washington lived in the 1970s until his death in 1987; which is next to the former Cooper-Carlton Hotel (right), later renamed the Del Prado Hotel.

That’s a 1920 scene above. Lake Michigan is immediately left, but out of the frame. The hotels look north on Cornell Park, donated to the community by Hyde Park founder Paul Cornell. Here’s the view from the Del Prado’s rooftop restaurant veranda in 1956 when my parents held their wedding reception.

The 1923 Belden-Stratford at 2300 N. Lincoln Park West is a fabulous North Side example of the apartment hotel, designed and built first by the 1926 Shoreland’s architect and general contractor. Shockingly, even though it’s on the National Register of Historic Places, the Belden-Stratford is not a city landmark. I mean c’mon—the old White Castle on Cermak is a landmark, which is good and right, but not the Belden-Stratford?

“With its recent big money restoration, the Belden-Stratford indeed seems like a no-brainer for landmark status,” explains Tim Samuelson. “But before the restoration, it gave the impression of being a seedy dump. And it suffered many seemingly irreversible changes which were miraculously reversed in the recent restoration.”

The Belden-Stratford’s rehab does look nothing short of supernatural. Check it out at the building’s official website, and a great look here, just before its grand reopening this summer, from Crain’s Dennis Rodkin.

One of Tim Samuelson’s personal favorites is the Webster Hotel, just south of the Belden-Stratford.

“The former first floor ballroom that’s now a pre-school was the temporary recording studio of Victor Records in the mid-1920s,” says Samuelson. “Many great records of the era were recorded there, including classic jazz pieces by Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers.”

I’m especially partial to the former Belle Shore Apartment Hotel for its gorgeous green terra cotta. It’s a landmark, but oddly, its entire Landmark Designation report is in black-and-white. Here’s a look instead from Google Streetview—for the green, and to give you an idea of what a large, nice-but-no-ballroom apartment hotel looked like:

Of Chicago’s grand apartment hotels, the Shoreland was topped only by the magnificent Edgewater Beach Hotel. The Edgewater Beach complex was so monumental, its address was often listed simply as “5300 block of Sheridan Road.”

The Edgewater Beach Hotel and its Tower addition were demolished in 1970-71. What an incomprehensible loss for Edgewater, and the city.

Luckily, the University of Chicago bought the declining Shoreland Hotel for a student dorm in 1974, selling it for redevelopment in 2004. The hotel was landmarked by the city in 2010 and rehabbed into “luxury” apartments by Studio Gang, which produced a short video of their work well worth a look.

So the Shoreland endures, though like most of the South Side, it’s forgotten by the larger city. Heck, even most of the neighbors have no idea they could be tracing famous footsteps as they walk their dogs past it on the way to the lake.

Today, if you drive south on DuSable Lake Shore Drive to the Museum of Science and Industry, the Drive’s terminus for most non-South Siders, you’ll glimpse the Shoreland just before you arrive.

Below, I’m pleased to include a literally and figuratively soaring photograph of the Shoreland by 606 Vision, known on Twitter as @Jay3130Jay. Contact him there if you’re looking for a photographer for anything from architecture to weddings. He also does a gorgeous Chicago calendar that makes a great gift. Back to the Shoreland: The only major differences here from the hotel’s heyday are at the ground level entrance:

The horseshoe drive may have been a different color, and it curved around a huge fountain. The fancy wrought-iron covering at the front door—which is a porte cochere, as Max Chavez from Preservation Chicago kindly informed me—was painted a lighter color in earlier years, though not necessarily the glowing gold often depicted in tinted postcards.

The Shoreland’s design is called Spanish Renaissance Revival—hereafter “SRR”—a style that began with the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, a sort of world’s fair in San Diego honoring the opening of the Panama Canal.

SRR “dominated commercial and residential architecture” in the US for a few decades, per the city’s Landmark Designation Report. SRR took every possible Spanish influence and literally threw it at the walls. It all stuck, including “late Moorish architecture, medieval Spanish religious architecture, the Baroque architecture of colonial Spain, and the American Pueblo and Mission styles.”

Chicago’s SRR style buildings, like so many others here of that era, feature beautiful terra cotta cladding—because it’s pretty; because it’s lighter and cheaper than stone; and because it’s fireproof, a major plus in a city that had so recently almost burned to the ground. The Shoreland’s terra cotta ornamentation came from the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company, one of three major manufactures once located right here in Chicago. Now, I am told by Will, the Chicago Brick Guy who leads terrific walking tours in many neighborhoods, there are only two terra cotta companies in the entire country.

The rest of the Shoreland, even the back, is covered with “buff-colored Kittanning brick”—Kittanning being a venerable, still extant Pennsylvania company.

For more close-ups of the Shoreland’s exterior, scroll down to the photo spread section titled “The Shoreland, 2023.”

Wondering what this website is all about anyway? Find out here.

Money money money mon-ey, MONEY!

The Shoreland began as a gleam in the eyes of its developers and investors, the dollar sign kind you see in Loony Tunes.

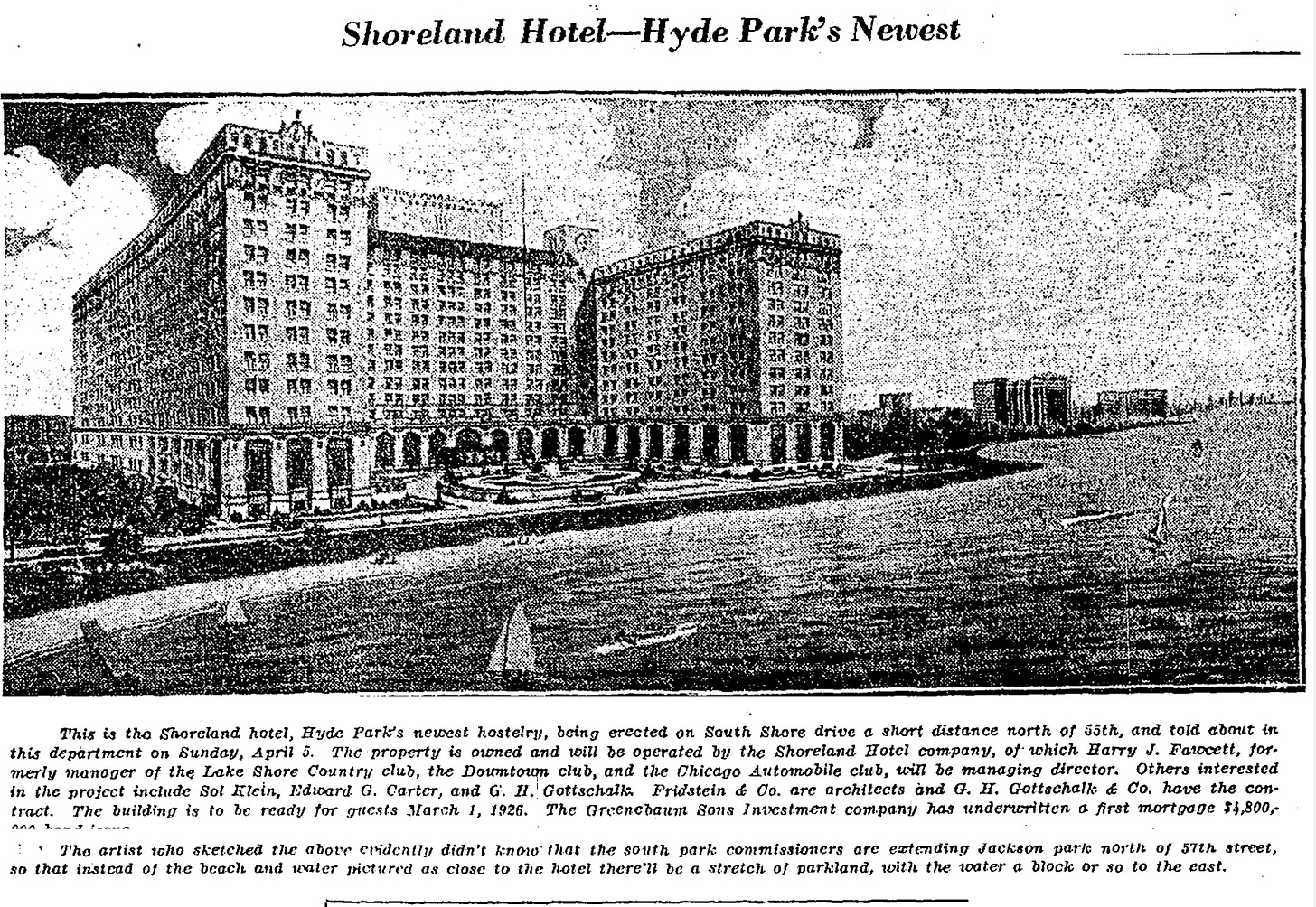

Basic stats: The hotel was designed by architects Fridstein & Co. to rise 13 stories, but “with foundations capable of carrying five additional stories later on”. Meyer Fridstein also designed the Belden-Stratford Hotel, Congress Theater, Logan Theater, and Tivoli Theater. The general contractor was G.H. Gottschalk & Co., with Avery Brundage builders.

The Shoreland cost $6-$10 million depending on who you believe—$100-$200 million in 2023, per the Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation calculator. Not shabby! No wonder the hotel billed itself as “World’s Finest Residential Hotel” in its first ads—though they soon ramped down their slogan just slightly to “Chicago’s Finest Residential Hotel.”

A lot of people owned a piece of the Shoreland early on, since it was partially financed by a $4.8 million bond issue ($85 million in 2023) from Greenebaum Sons Investment Company, which called itself the “oldest first mortgage banking house.”

Shoreland general contractor Gustav Gottschalk already lived next door in the gorgeous Rapp & Rapp-designed Jackson Shore Apartment building, which his company had built ten years earlier…

…while Greenebaum & Sons Investment Company President Moses E. Greenebaum, whose company had also issued the bonds for Jackson Shore, moved into the Shoreland.

This early drawing accurately shows the Shoreland’s original proximity to Lake Michigan, with nothing but the modest street Shore Drive separating hotel grounds from the beach…

…until landfill extended Burnham Park and the early version of DuSable Lake Shore Drive south from downtown to meet Jackson Park, just a block south of the Shoreland. The final leg of that project began during the Shoreland’s construction. As Tim Samuelson points out, the newly reconfigured lakeshore left the hotel “literally high and dry.”

The Shoreland naturally continued touting its waterfront access, with a slight pivot. Here’s a bit from the April 1925 Tribune that probably came straight from the hotel’s publicity folks:

“The Shoreland will occupy one of the most attractive hotel sites in the world. The new park land now being filled in along the shore from Jackson park to the Chicago Beach hotel [at 51st Street] will extend about 2,000 feet into the lake directly in front of the Shoreland….When the shore development between Jackson park and the loop is completed a magnificent park and drive will connect the Shoreland with downtown Chicago, so that motorists can drive from Grant park to the hotel without meeting a ‘stop’ signal.”

Supply your own 21st century (and beyond) traffic and/or construction joke here.

Whether you consider swapping beach for parkland across Lake Shore Drive a plus or minus, the landfill process would not have been pretty. “In its earliest years, the area in front of the Shoreland was a horrific construction site of landfill activity,” says Tim Samuelson. The otherwise tireless Shoreland publicity team left that detail out.

The Shoreland and nearby communities naturally celebrated the enhanced downtown access, despite the temporary mess. When the new parkland and road were complete, the Shoreland looked out over Leif Erickson Drive—the original name for DuSable Lake Shore Drive south of the Chicago River, though Chicagoans already called it “the Outer Drive.” *Scroll to end for more on the Drive’s naming.

Leif Erickson Drive finally opened in its entirety in 1929. The 23rd-31st Street section opened in 1928, as did the portion fronting the Shoreland from 51st-57th Streets. That left the 39th-51st Street chunk to complete the project in 1929. The whole thing cost $869,000, funded by a $7.5 million bond issue by the South Park Commission, per the Tribune. (The Chicago Park District was split into three separate entities back then—South, West, and Lincoln Park for the North Side.)

So in 2023 money, today’s south DuSable Lake Shore Drive initially cost $15.5 million, from $135 million in bonds. That’s still quite a steal. South Park Commission President Ed Kelly—who would become Mayor Ed Kelly just four years later—cut the ribbon in 1929, followed by a gala parade down the length of Leif Erickson Drive, culminating in a 600-person banquet at—you guessed it, the Shoreland.

Below, the Shoreland is the structure in the background on the extreme left. The buildings at the front right are the Sisson and Cooper-Carlton Hotels on 53rd Street, overlooking Cornell Park, which retains the exact same path through it from 53rd Street today, though Chicago Beach Drive is gone. These days, DuSable Lake Shore Drive has exits at 53rd and a bit north of 51st Street.

“The intentions were that the Shoreland would be a convenient vacation getaway for Chicagoans,” says Tim Samuelson. “It was kinda like people going to Vegas. Targeted to everyday folks who wanted a fantasy classy vacation experience. The rooms were actually fairly small.”

The Shoreland’s many original eager investors did not expect that the nearby Fine Arts building from Jackson Park’s 1893 Columbian Exposition would soon become the Museum of Science & Industry. Everybody thought the Fine Arts building was destined to be a convention center attracting thousands of overnight customers.

What the investors also did not expect, but you may have seen coming in your 20/20 rearview mirror, was the infamous stock market crash starting on Black Monday—October 28, 1929.

That dark day in U.S. history marked just three years after the Shoreland’s grand opening. The Shoreland’s business plummeted, bringing a famous Chicago name into play by March 1930.

By 1932, the Shoreland was in receivership managed by Chicago Title and Trust. The hotel reported $56,000 in monthly income and $286,000 in cash—versus a judgement for 1927-1930 unpaid taxes totaling $193,000 ($4 million in 2023).

The 1933 “A Century of Progress” World’s Fair, held on Chicago’s lakefront just a bit farther north, helped a little.

As the Tribune noted that summer, “Several big hotels outside the loop, many of which are in receivership, reported that they are now running from 85 to 100 per cent occupancy where they were only 50 to 70 per cent occupied before the Exposition opened.” The Shoreland was among the ailing hotels hoping to pay off all its taxes with Fair money.

Money can drive some people out of their minds

On July 28, 1932, Shoreland developer Gustav Gottschalk came home from his office downtown at 105 W. Madison. Mrs. Gottschalk and the couple’s three teenage children greeted Gustav as he walked in the door of his spacious home at Jackson Shore Apartments, next to the Shoreland. The family later said Gustav was carrying a thermometer, and told them he was going to hang it outside his bedroom window.

The Jackson Shore apartments are especially roomy—only two per floor, and as you can see, the building is nearly as deep as the Shoreland. The 1916 Tribune article above noted that each unit would feature nine to 12 rooms, all including four bathrooms, “library, breakfast bay, orangeries, solariums, etc. Living rooms will be 17 x 20 feet”.

This explains why the Gottschalk family had no idea that Gustav either jumped or fell from his 9th floor bedroom window into the backyard below, until a neighbor came to tell them.

“According to his family, Gottschalk had no worries and had been in his usual good spirits,” the Tribune reported the next day. “He was, they added, subject to spells of dizziness.”

The family doctor backed up the family’s claim of dizzy spells. “A chisel, hammer and a screw driver, with which Mr. Gottschalk apparently had been working, were on the windowsill,” according to the Daily News.

We can only speculate, so let’s do it: I speculate it’s unlikely that a wealthy executive who suffered from dizzy spells would personally install a thermometer outside his luxury apartment’s 9th floor bedroom window. Or that his family would listen to his plan to do so, nod, and leave him to it.

Why would Gottschalk’s family deny that he had taken his own life? Suicide was even more verboten a topic in polite early 20th century society than it is 100 years later. Families at that time often didn’t even want to admit when a loved one died of cancer, as if it were a moral failing. Even the city’s 2010 Landmark Designation Report delicately notes that the Shoreland was Gottschalk’s “last, most ambitious, large-scale apartment hotel project,” without mentioning why.

So Gustav Gottschalk was probably one of the many suicides associated with the Great Depression. According to a study of U.S. suicides, the number varied from 10.2 to 22.2 per 100,000 between 1928-2007, with the peak in 1932, the year Gustav plunged nine stories from his bedroom to his backyard.

Moses Greenebaum, whose firm issued the bonds financing the Shoreland, died in his home at the Shoreland on June 22, 1934.

At 76, Greenebaum had lived a long life for that time. Still it seems likely that stress from the Depression may have played a part in his death, officially from pneumonia, given this nugget of information from the Tribune’s obit:

“Last October, in a letter to the stockholders of the Greenebaum Sons Investment company, Mr. Greenebaum related that he and his brother, James E. Greenebaum, had put their personal fortunes of more than $5,000,000 into the company to carry it through the depression. There was no legal obligation to do this, but the veteran banker explained that he felt a moral obligation to ‘save the good name’ the family had built up over three-quarters of a century.”

Does it matter how much $5 million was in 1934 compared to today? The Greenebaums put their entire fortune into attempting to protect their investors, and if the Shoreland is any indication, it wasn’t enough.

The combination of Greenebaum’s and Gottschalk’s deaths probably explains the rumor that a nameless builder or developer or financier of the Shoreland leapt to his death from a Shoreland window after the stock market crash. Again, there was no Elvis at the Shoreland, and no major executive involved in the hotel’s creation leapt directly from the building itself. The architect, Meyer Fridstein, would die a natural death in 1964 at Michael Reese Hospital.

For the love of money

Within two months of Greenebaum’s death, the Shoreland was reorganized and the 5,000 bondholders became the owners. With the increased business from the nearby 1933 World’s Fair, which ran through 1934, the receivers managed to pay all the foreclosures fees and back taxes, plus set aside reserves and pay the bondholders about $2 on every $100 of investment. In other words, everybody lost 98 cents on the dollar.

Not everybody was OK with that payout. About a quarter of the former bondholders banded together for a four-year legal battle with receiver Chicago Title & Trust over its management of the Shoreland, which then turned into a fight over accepting bids to sell the hotel.

The Shoreland finally sold for $2.25 million in 1946. Remember it was built for at least $6 million in 1926. In 1946, the hotel should have been worth a minimum $6.7 million, according to the BLS inflation calculator—not the large increase we usually see over 20 years, due to the Depression. But a lot more than $2.2 million.

Almighty dollar

You’d never guess from the early Shoreland’s constant parade of social events that a Great Depression was underway. Naturally, I wondered just how rich the Shoreland clientele would have been back then.

According to Chicago Cultural Historian emeritus Tim Samuelson: “There were some fairly upper middle class people who lived there. But the wealthy would never go to a place like that.”

So the Shoreland was not the Riviera, or even the Palmer House. Royalty didn’t spend a season at the Shoreland. Still, the early Shoreland was possibly the most fashionable address on Chicago’s south shore. Some rich people clearly did stop in—if John D. Rockefeller Jr. counts.

“John D. Rockefeller Jr., a medium-sized, old-fashioned multi-millionaire with high shoes and a stickpin in his cravat” chatted with a Chicago Daily Times reporter in his Shoreland suite in 1941. Admittedly Rockefeller was in the neighborhood for the University of Chicago’s 50th anniversary, but once in Hyde Park, he chose the Shoreland.

At least one multi-millionaire lived at the early Shoreland with his wife and children—Alex D. Nast, with the Commercial Investment Trust—until he died in 1936. Nast left an estate then worth $2 million—$44.6 million in 2023 money. Other permanent Shoreland residents included heads of prominent companies, such as Jacob Schnadig, president of the Pullman Coach Company, who died at his Shoreland home in 1935.

Crime in the Shoreland over the years also points to early residents with healthy portfolios. Every few years, some resident would somehow lose jewelry valuable enough to buy real estate. The best story definitely belongs to Mrs. B.J. Ettelson. Her $10,000 of stolen jewelry would be worth about $200,000 in 2023. You’ll want to read the details on this one:

Shoreland clientele were a good market for Cadillac sales.

And the Shoreland was the definition of swank, from its two ballrooms to an 18-hole golf course improbably located in the basement, with two sand traps and a water hazard.

Still.

Money can change people sometimes

“The Depression put places like the Shoreland on the skids,” says Tim Samuelson. “That big remodeling only after 11 years was an attempt to revive itself along the old business plan. But it never quite recovered. It transitioned into largely being apartments. It was off people's radar as a resort.”

In the mid 20th century, the Shoreland’s fortunes continued falling along with the rest of the South Side. The hotel is still looking pretty good in the 1954 picture below, but it was sold again that year for just $6 million—the low end of its possible construction cost in 1926 without even adjusting for inflation. With inflation, it should have been worth a minimum $9 million in 1954.

By 1959, the Shoreland had become so common that the army relocated a group of 90 WACs (Women’s Army Corps members) there from the Riviera Hotel at 49th and Blackstone. The Riviera was so common, it was being demolished.

Wealthy and upper middle class people had increasingly stopped flocking to the South Side by the end of World War II, a trend that only accelerated afterward. How come?

That question gets passed over quickly in other accounts of the Shoreland, and I understand why. The answer is Chicago’s racist housing segregation and its aftermath, a painful topic covered by entire books. I recommend Arnold Hirsch’s “Making the Second Ghetto” as a foundational text which focuses specifically on Chicago. We can’t reprint Hirsch’s book here, but let’s go over some of his major points:

By 1900 Chicago’s then-small Black population of 30,150 had been forced, by white animosity and restrictive racial real estate covenants, to concentrate in the South Side’s so-called “Black Belt.” The area started out only about a quarter mile wide, from 22nd to 31st Streets. The Black Belt expanded as Chicago’s Black community grew with the First Great Migration fleeing the Jim Crow South before the Depression—despite the notorious 1919 race riot, in which mainly roving bands of whites attacked Blacks. Ultimately, 23 Blacks and15 whites were killed.

By 1930, the Black community had grown to 233,903. Along with a small West Side community and several scattered South Side enclaves including in Hyde Park, the Black Belt now stretched to 63rd Street, running from Wentworth on the west to Cottage Grove on the east, which is Hyde Park’s western boundary.

Like most immigrants from a hostile land, Blacks from the South arrived poor. Besides housing segregation, they would remain disproportionately poor as a group compared to white Chicagoans due to the racist job discrimination they would also find in the North. Black Chicagoans, again as a group, would just begin to catch up with the end of the Depression and onset of war production jobs in World War II.

Chicago’s city-wide housing shortage crescendoed by the late ‘40s, after the near halt of construction during the Depression and war years. The Chicago Commission on Human Relations estimated in 1947 that the city needed 200,000 new homes, just as the population jumped with returning veterans, the ensuing postwar Baby Boom, and the Second Great Migration.

As the war ended, “Within the main South Side Black Belt, it was estimated that 375,000 blacks resided in an area equipped to house no more than 110,000,” writes Hirsch. The overcrowded conditions meant bad safety and sanitation. The rat population exploded, with rat attacks on sleeping children. “One alderman…labeled the entire Black Belt a ‘gigantic fire trap.’”

With the Second Great Migration, the city’s postwar Black population grew again from 277,731 in 1940 to 492,265 in 1950, and 812,673 in 1960. Black Chicagoans finally broke out of the Black Belt in these postwar years, helped by the outlawing of racial real estate covenants by the Supreme Court in 1948. More importantly, Hirsch points out, a complex process of push and pull elements spurred rapid white flight from South Side neighborhoods surrounding the Black Belt—followed by resegregation and, in many areas, disinvestment and deterioration.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), created in 1934, helped drive that cycle by making mortgage redlining—previously only a private bank lending practice—a government policy too. Redlining wouldn’t end officially until the 1968 Fair Housing Act. The FHA approved white mortgages, especially mortgages in the suburbs—a phenomenon that really took off when housing construction began again after World War II, concentrated in outlying neighborhoods and suburbs. FHA mortgages and Chicago’s burgeoning expressway system paved the way for better-off whites to leave—400,000 of them, from 1940-1960 alone.

As the suburban exodus progressed, housing began opening up in white neighborhoods around the Black Belt. Black Chicagoans were ready to move in. Hirsch describes how redlining distorted the process:

“As the expanding Black Belt approached white residential areas, those neighborhoods entered what realtors called a ‘stagnant’ period. Whites no longer bought homes in the community and blacks had yet to make their first appearance.”

At this point, “lending agencies refused to grant mortgages to whites in such ‘threatened’ areas, and, of course, they demurred to providing financing to the first blacks to ‘break’ a block. With the future of the area uncertain and income restricted, landlord and homeowners often cut back on the maintenance of their properties. Deterioration thus frequently set in before blacks moved into the community.”

Once that redlining process started, unscrupulous real estate brokers used block-busting tactics to scare off remaining white residents. They low-balled panicked white sellers, then flipped the property to Black buyers at exorbitant prices.

Often unable to procure regular mortgages, many Blacks were forced to buy on contract, a system in which buyers built no equity until they finished paying the entire sum at high interest rates—and could lose their homes after missing a few payments. The financial stress also meant many families couldn’t afford home repairs, leading to more deterioration in the now resegregated Black neighborhoods. Black Chicagoans trying to escape slum conditions were dogged by many of the same problems as they moved outward across the South Side.

It was an often ugly time. There were more race riots through the 1940’s and 50’s, though less deadly than 1919, particularly when Blacks moved into CHA projects in white neighborhoods. At the same time, the first new Black residents in all-white neighborhoods endured everything from cold shoulders to fire bombings, followed by white residents in changing neighborhoods becoming targets—and this continued all the way into the early ‘70s. For more, see these THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 posts: July 9, 1972: “No Welcome Mat”; July 10, 1972: South Side Fire Bombs; and July 10, 1972: “Why Whites Stay.”

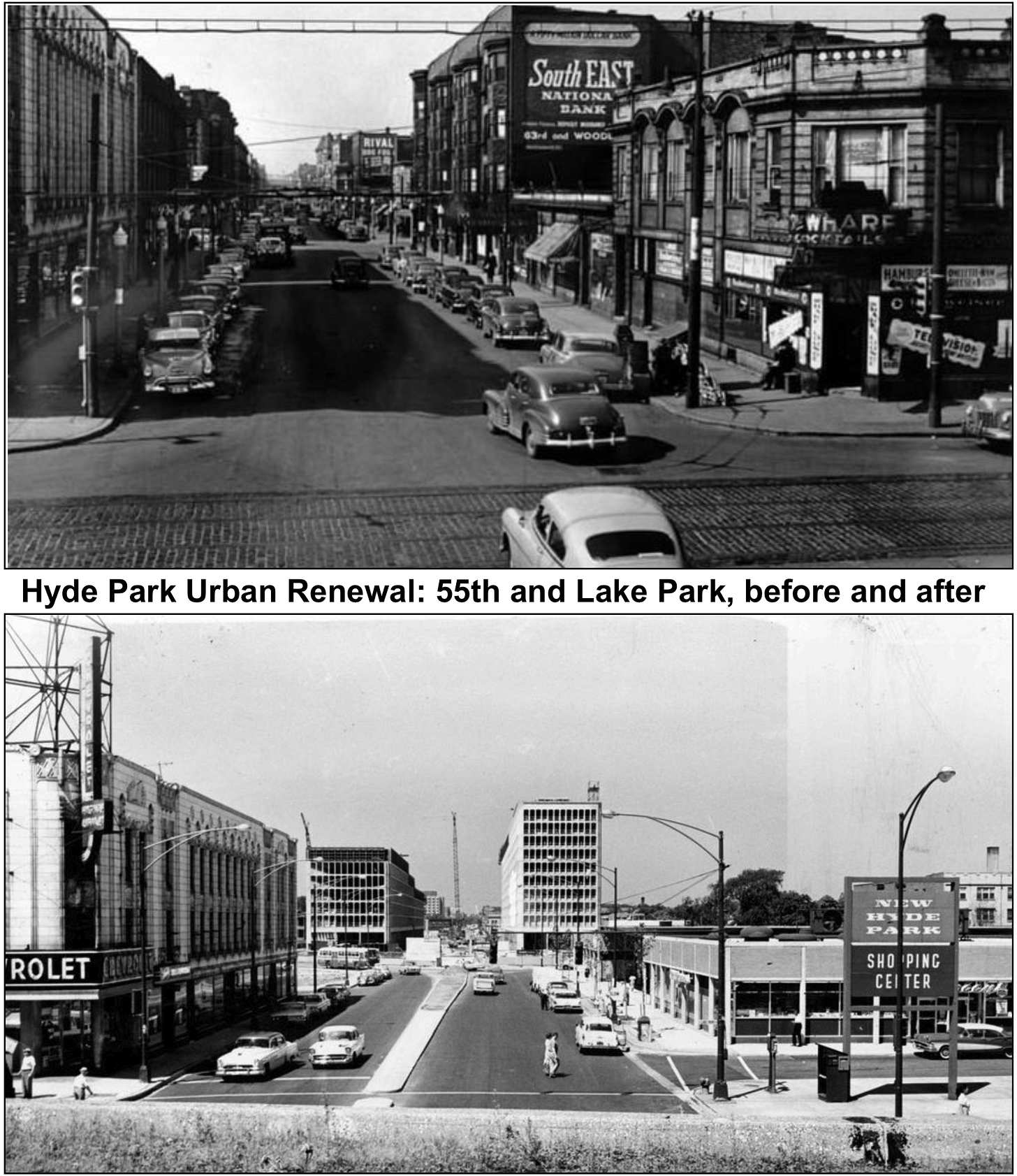

Hyde Park and the Shoreland were smack in the middle of these sweeping changes. As Hyde Park experienced rising crime and blighted buildings subdivided into too many tiny apartments through illegal conversions, the University of Chicago led the city’s first federally-funded “urban renewal” effort in Hyde Park. This, too, could take an entire book.

The controversial urban renewal program bulldozed whole blocks of buildings starting in 1955. Older multi-unit buildings were swept away for single-family townhouses, an I.M. Pei-designed midrise apartment building in the middle of 55th Street, and two shopping plazas. Hyde Parkers will never stop debating the two-decade process.

In the end, Hyde Park remained a middle class integrated neighborhood—but it was no playground for high society types playing cards and attending club meetings at fancy schmancy hotels.

In 1971, the Tribune’s Steven Pratt talked to doormen around town about the changing modern demands of the job. Shoreland doorman Bill George, then 42 and sporting a fraying red hotel coat, introduced the article’s dismal section about “the once grand hotels” that had been “cutting back.”

“It keeps getting less and less busy,” Bill George told Pratt. “This place used to be a place for kings and queens, not in my time but before.”

George, who’d only worked for the Shoreland for four years, was a bit off. There were never any kings or queens at the Shoreland. Oh those rumors.

“George…was standing by a never-used doorman’s cubicle in front of the Shoreland entrance,” wrote Pratt. “He pulled his coat together where there was a button missing and said, ‘The doormen here used to look like the queen’s army.’”

The University of Chicago bought the hotel for a dorm in 1974, for just $750,000 according to Forgotten Chicago, which got that number from a Hyde Park Historical Society webpage no longer available. I couldn’t find that purchase price elsewhere, but why not? That would be a paltry $4 million in 2023 dollars, and just $280,000 in 1926 when the Shoreland was completed for $6-$10 million.

As part of UC, the Shoreland initially housed both former residents and new students. Neighbor Bette J. Glick wasn’t impressed with that incarnation of the hotel, judging from her 1976 letter to the Tribune.

By the time I first stepped inside the Shoreland in the mid 1980s, it was an undeniable dump.

“The Shoreland is a dilapidated relic, and sinking more money into this albatross would be a mistake,” wrote John Lovejoy in 2003 in UC’s student newspaper, the Maroon, as the campus debated the hotel dorm’s future. “The less I know about the various molds, spores, and allergens dwelling in the insulation, carpets, and ceilings, the better,” noted Lovejoy after a lengthy list of other equally valid complaints.

“The dorm, far from campus and showing its wear but offering apartments with views of the lake, was unique in its ability to inspire admiration and disgust among its residents,” wrote Rob Katz in the Maroon a year later, as UC sold the Shoreland for development.

In 2004, just as in 1954, the Shoreland went for only $6 million, the low end of its original construction cost in 1926. With inflation, it should have been worth $63.6 million.

The Shoreland’s arc prior to its 21st century rehab can be traced through its newspaper ads. Here’s a sampling of the lavish full-page ads that ran in Chicago papers running up to the hotel’s June 1926 opening.

In the ‘30s, post Crash, Shoreland ads shifted from an emphasis on outrageous luxury to classy yet practical living, in much smaller ads—perhaps 1/8 page at most.

The ‘40s ads remained a modest size, selling the Shoreland as a smart place to live.

Shoreland advertising dried up in the ‘50s. A grand total of two ads ran that decade in the Tribune, in 1951 and 1952, and they weren’t even specifically for the hotel.

Before we move on, you might be jonesing for some O’Jays. I know I am.

Life and Death at the Shoreland

To sift through Shoreland newspaper clips is to see how Chicagoans lived fashionably in the first half of the 20th century—and how they died in the fashion of the day, naturally or violently. Both changed over the decades, along with the Shoreland itself.

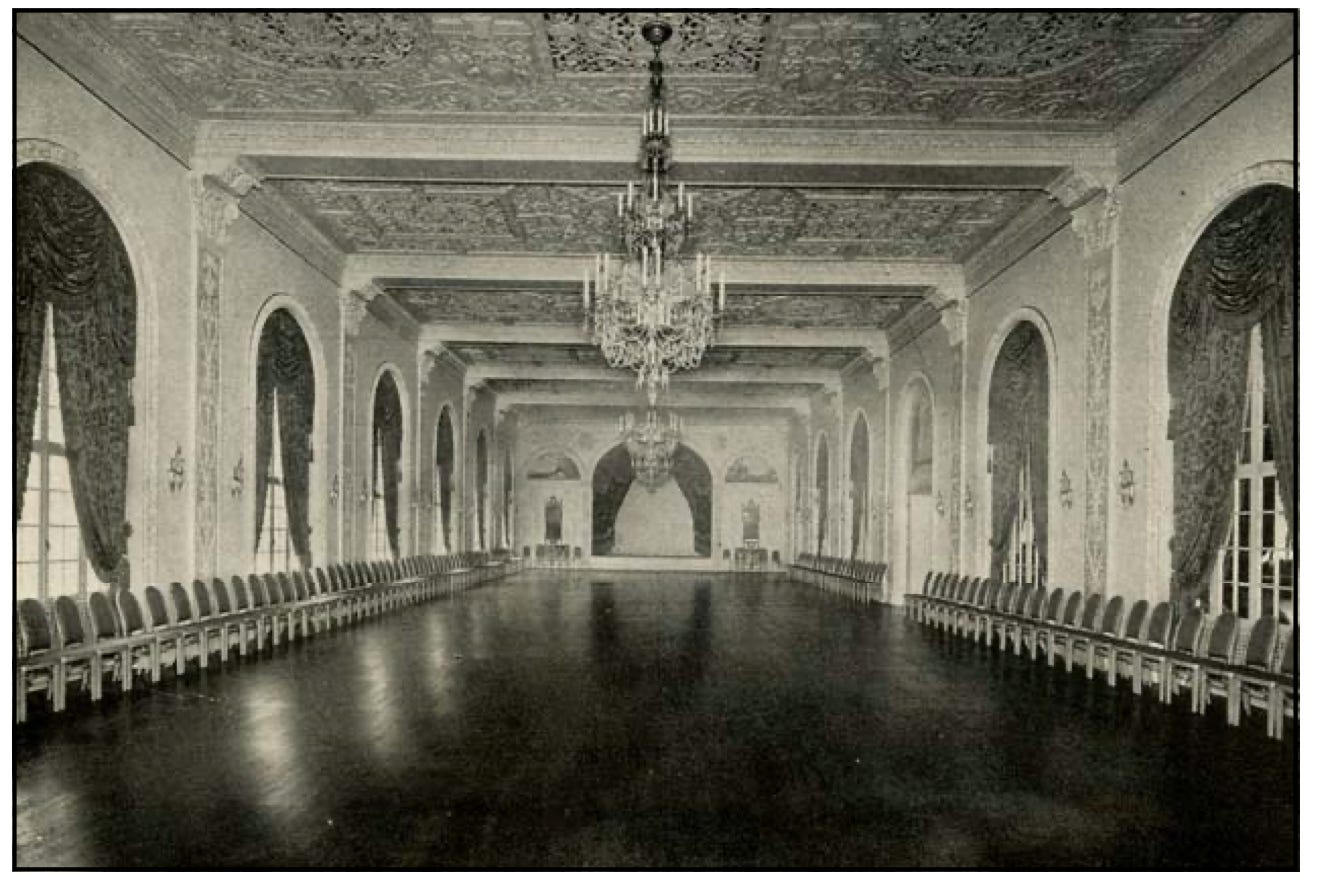

In life, Shorelanders danced and celebrated everything from weddings and proms to Christmas and Purim in the hotel’s breathtaking Crystal Ballroom and its South Ballroom. The Crystal Ballroom was located on the second floor central section of the hotel, beyond an open mezzanine balcony reached by two flights of marble stairs rising from either end of the lobby.

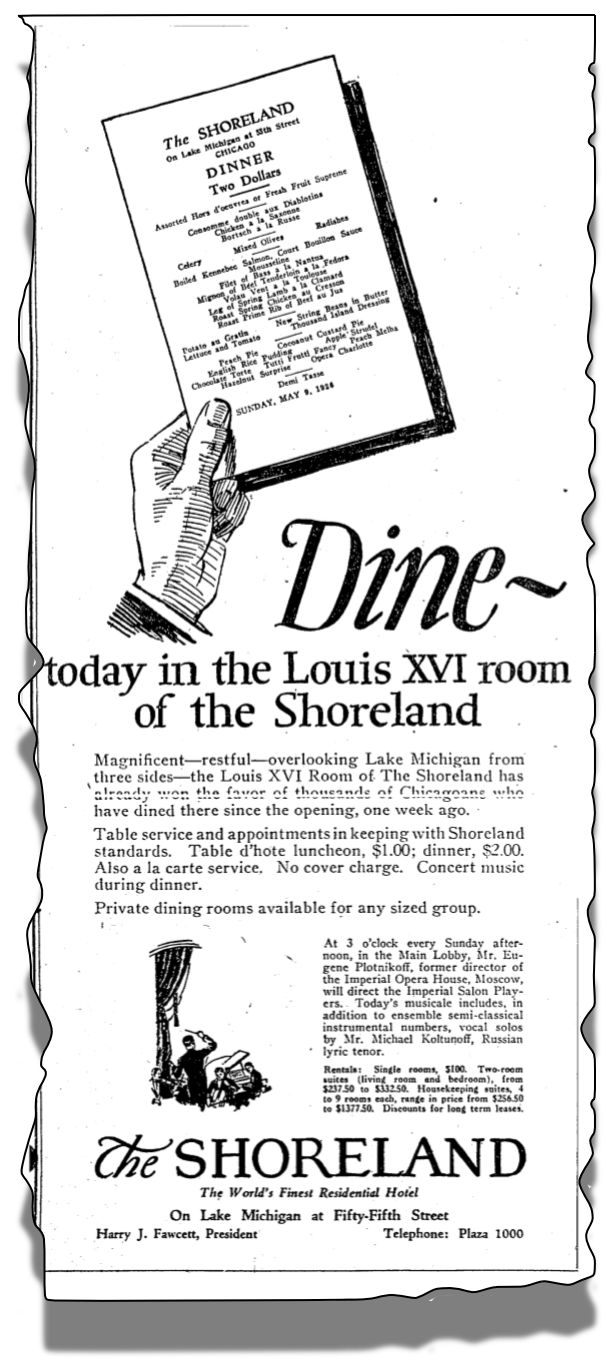

They feasted in the Louis XVI Room, the main hotel dining room the size of a ballroom itself—

—or dined in one of the hotel’s many other public spaces, inside and out.

The main floor of the hotel’s two wings housed the South Ballroom on one side, and the Louis XVI Room on the other. Both featured soaring two-story ceilings and gorgeous French doors.

Unfortunately, both the Crystal Ballroom and the Louis XVI Room were reconfigured into office space during the early 21st century rehab. Here’s a picture from the Mac Properties Facebook page showing today’s Crystal Ballroom…

…and a look through the windows of the former Louis XVI Room, where employees work beneath a sea of hanging fluorescent ceiling lights and an occasional incongruous grand chandelier.

The South Ballroom, seen here from the driveway, has been split horizontally into two floors and subdivided into apartments.

The early Shoreland was all about high society, in a day when newspapers devoted entire daily pages to upper class weddings, clubs, card parties and plays.

Society events segued into pop culture by the ‘40s, like hosting the preliminary contest to select South Side vocalist finalists for the then annual Chicagoland Music Festival in Soldier Field.

Music was aways a Shoreland highlight, starting at its 1926 opening with Eugene Plotnikoff, billed as former conductor of Moscow’s Imperial Opera House. Plotnikoff directed orchestral concerts in the lobby on Sunday afternoons. Other newspapers clips note the “dreamy waltzes” of the Shoreland Hotel Orchestra. Here’s a tinted look at the original Shoreland lobby where guests listened to Eugene Plotnikoff’s classical music.

Chicago Cultural Historian emeritus Tim Samuelson describes the original lobby as “1920s Norma Desmond-style Spanish-ornamental.”

Jazz soon invaded the Shoreland with dancing and the Herbie Mintz Orchestra taking over the Louis XVI Room on Sunday nights. The lobby was quickly updated to Art Moderne in the 1930s, seen below in a colorized postcard courtesy of John Chuckman. You can compare this color version with a period black-and-white photo here from a page of Shoreland pictures on the Chicago History Museum website…

…or by visiting the Shoreland yourself to view the rehab, a faithful reproduction, minus the furniture and drapes. Too bad they couldn’t perfectly replicate the cool ceiling light fixtures. Patrick Steffes explores the Shoreland’s 1930s do-over by modernist Chicago architect and designer James F. Eppenstein at the wonderful website Forgotten Chicago here.

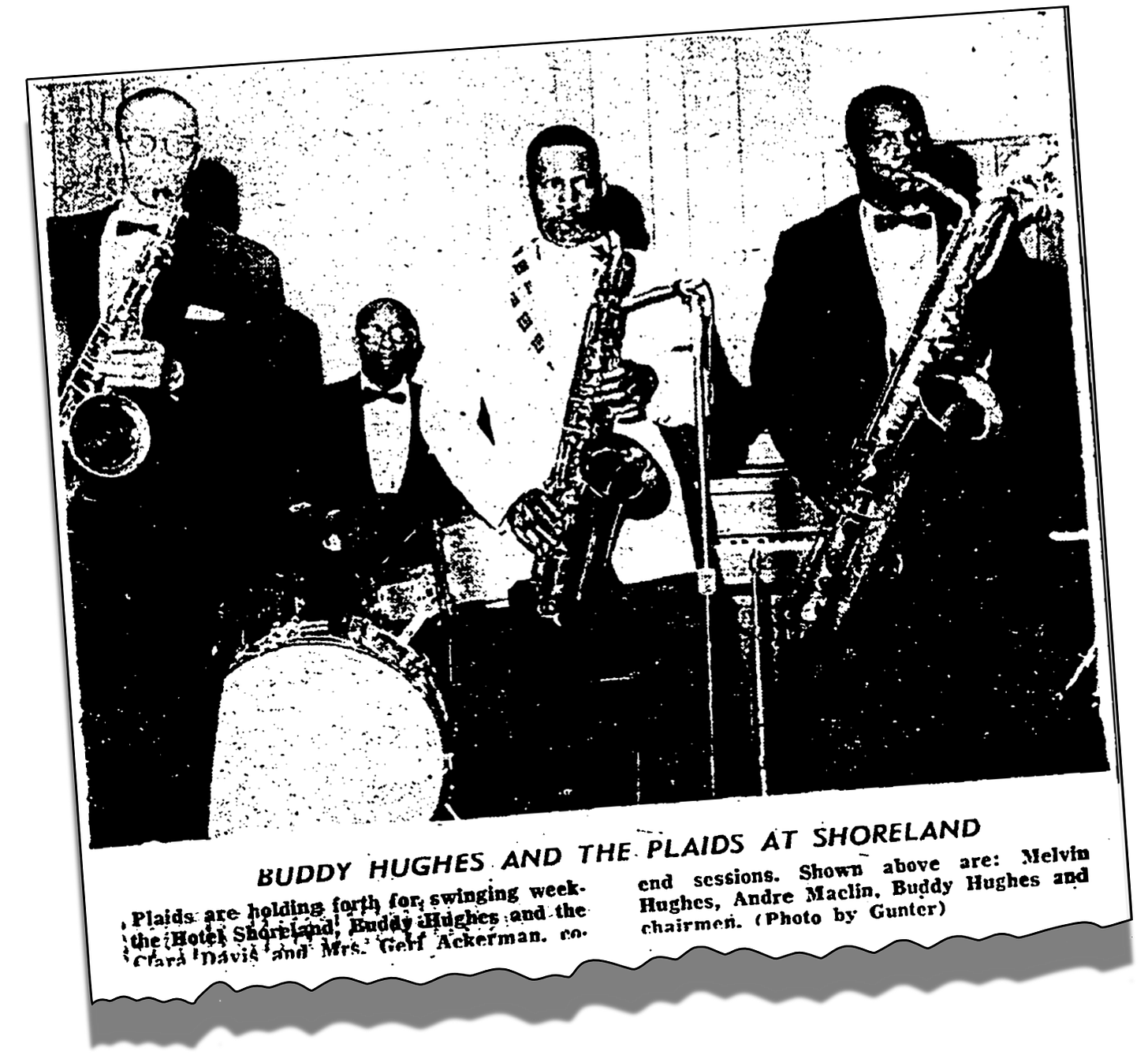

The Shoreland was still swinging in 1965 with Buddy Hughes and the Plaids…

…sometimes appearing as “Buddy Hughes and the Swingtones” at the “28 West Discotheque Supper Club.”

It’s not clear which of the many spaces in the Shoreland hosted the Discotheque. I would’ve liked to check out the Plaids just to see Lee Smith.

While early high society Shorelanders played bridge and Mahjong and attended lectures by the likes of England’s poet laureate upstairs, there was a lot going on downstairs—and up in the attic, and behind the scenes. The working Shorelanders upholstered hotel furniture, washed and ironed clothes and linens, cooked and served food, scrubbed floors, and manned the front door in snappy uniforms.

There was quite a lot of cleaning to do for women like my Gramma.

The janitors could be a mischievous crew, if janitor Victor Powell’s experience in 1942 means anything. Powell was born in Georgia, according to the 1940 census, which marks his race as “Neg,” meaning “Negro.” So Powell was part of the Great Migration of African-Americans moving north in the early 20th century. He rented a room at 123 E. 45th St. in Bronzeville.

In 1940, Powell was 32, working as a porter in a barber shop, and reported earning $780 in 1939—about $17,000 in 2023. Two years later, he was likely riding streetcars to work at the Shoreland, at least up until December 6, 1942.

The Chicago Daily Defender reports that Victor Powell was gathering odds and ends from the 11th floor to cart away via the freight elevator on December 6. He stepped into the pitch black elevator, believing one of his co-workers was pranking him by turning its light off.

You wonder what practical jokes must have been going on among the janitors. As you’ve guessed, this wasn’t one of them.

“He stepped forward to reach for the light, but instead tumbled into space, the elevator having stopped at another floor,” per the Defender. “Retaining presence of mind, Powell grabbed the elevator cable, which doubtless saved his life. His hands were burned and lacerated by the cable, but it broke the force of the fall down to the basement.”

Powell was treated for a broken hip and internal injuries at Provident Hospital, Chicago’s first Black-run hospital, which had relocated from its original location to the former Chicago Lying-In Hospital at 432 E. 51st St. That building was later demolished for its 1982 replacement at 500 E. 51st St. Provident is now part of the Cook County public medical system.

If you know the area, it might occur to you that the University of Chicago hospitals are a bit closer to the Shoreland than Provident. After such a massive accident, you’d think Victor Powell would have been taken to the UC’s Billings Hospital. But while the University of Chicago was far ahead of its time in always accepting Black, women, and Jewish students, UC’s medical school at this time did not allow its own Black med students to intern at its hospitals. And the UC hospitals mainly didn’t accept Black patients until some time in late 1947 or during 1948. Not finding a precise date elsewhere, I narrowed that time period down via newspaper archives. Just a year after Victor Powell fell eleven stories in a Shoreland elevator shaft, Lula Payne wrote this letter to the Defender:

Two years after World War II, a 1947 UC student protest charged that the few Black patients “who are admitted [to UC’s Billings hospital]—students, employees of the university and cases of special medical interest—are treated in private rooms to segregate them”. The protest succeeded, though oddly, none of the papers, including the Defender, specifically wrote about that outcome. The Defender just started reporting deaths of Black Chicagoans at Billings routinely by 1949.

That was too late for a badly injured Victor Powell to be taken to the closest hospital. Happily, the Defender reported Powell in fair condition at Provident a week later. I couldn’t find Powell in the 1950 census, but I also couldn’t find several of my own relatives where I knew they should be. Optimistically, Powell either moved or is in that census somewhere.

It looks like the Shoreland didn’t discriminate in hiring, though they probably discriminated in employee assignments. Before the late 1940s, it wasn’t unusual for want ads to specify “colored” or “white,” but in random checks, I didn’t see any Shoreland ads that did so. Here’s a 1943 Shoreland ad just underneath a Palmer House ad, showing the difference.

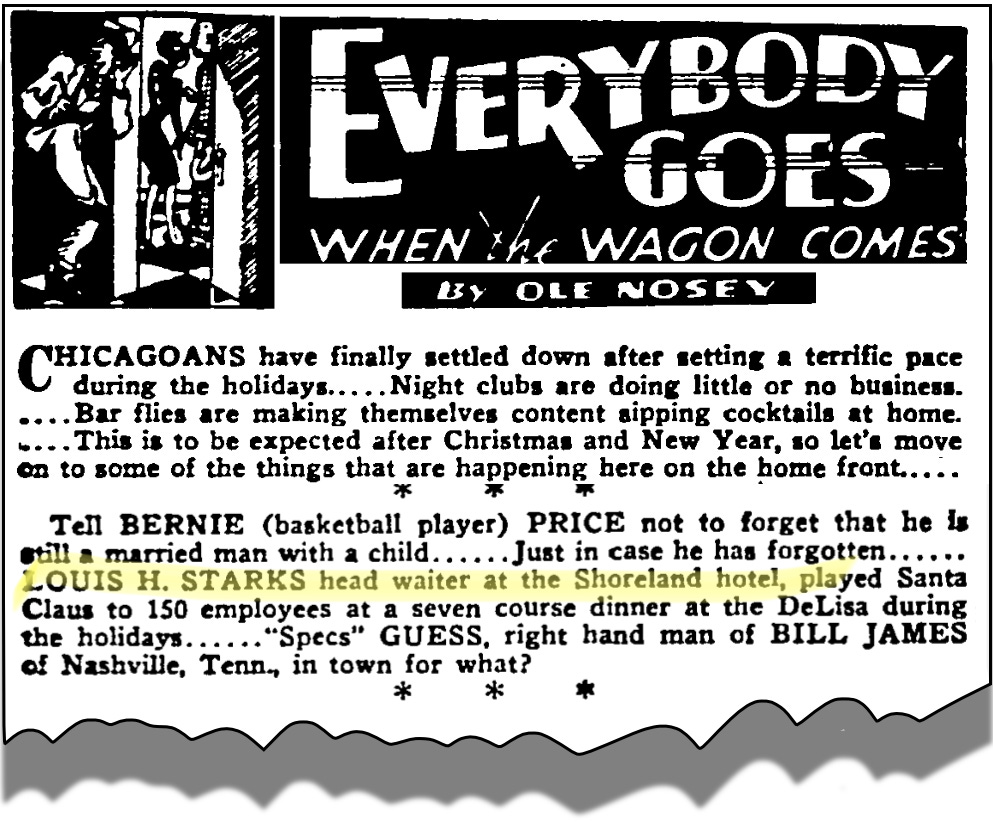

Here, a Defender gossip column in 1943 mentions that “Louis H. Starks, head waiter at the Shoreland Hotel, played Santa Claus to 150 employees at a seven course dinner at the DeLisa during the holidays.”

This could have been a dinner for Black Shoreland employees only, or for everyone. The Club DeLisa was a famed Bronzeville nightclub at 5521 S. State Street, known also as a “black-and-tan” in the parlance of the day, which meant it drew an integrated crowd as in the swinging picture below available via Wikipedia.

The early Shoreland employed Black Chicagoans, but did it welcome Black guests or residents? Without a definitive answer, we have to assume probably not. Newspapers don’t mention this—it would have been common knowledge unnecessary to say out loud for readers of the time. I couldn’t find anything on this at the Chicago History Museum, and the Hyde Park Historical Society and DuSable Black History Museum haven’t answered my information requests. If that changes, I’ll update. But even in the late ‘50s, South Sider Herman Roberts found it so hard to put up performers at his nightclub that he opened a chain of motels once well known all over the South Side. See THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972’s September 19, 1972: Herman Roberts for more.

Apart from a 1938 mention that three “Race students” attended the Lindblom high school senior prom in the Crystal Ballroom, the first solid indication that Blacks are in the Shoreland as guests comes in 1949. That year, the Shoreland hosted a conference on fostering civil rights and integration. The National Conference On Intergroup Relations drew coverage from all Chicago dailies, and a full page of pictures in the Defender. Here, the Defender treats the Shoreland as a typical destination for Black Chicagoans, as if this was always the case—but that’s how the Defender treated Black patients at UC’s Billings Hospital, so it doesn’t answer the question.

The Shoreland was a prom destination for Black high schools by 1951. Here’s the first Shoreland prom photo in the Defender, featuring a distant member of the publisher’s family.

The early Shoreland did welcome Jewish residents and guests, which wasn’t automatic in those days—even in this area with numerous Jewish congregations. Nearby at the southern end of Jackson Park, for instance, South Shore Country Club initially allowed Jews, then banned them in 1930 according to the Glessner House website. Per Glessner House, as wealthy white residents left South Shore in the mid 20th century and the club struggled, members considered allowing Jews back in—but the idea got voted down in 1967. The club folded instead and sold its land to the Chicago Park District in 1974, giving us the South Shore Cultural Center we know in 2023. South Shore Country Club never allowed Black members.

As we’ve seen from the society pages, Shoreland weddings were legion, but Shorelanders also got married a little too often...

…and of course, they divorced. I’m pretty sure they made this one into a movie with Irene Dunne as Sallie and Cary Grant as husband Arthur, who wishes he’d come up with a different name for his store.

Don’t miss the latest breaking stories from 1972, right here!

Death at the Shoreland

In those first decades of the 20th century, death rarely came for Shorelanders at the hospital. Without antibiotics and other advanced medical technology, people tended to drop dead unexpectedly, or die at home in their own beds. This was normal, and accordingly, there was clearly no stigma attached to natural death at the hotel.

Many early Shoreland families may have held wakes in their apartment homes, too, also normal practice at the time. One of my mother’s earliest memories is of her father lying in a coffin in their front room—just across Jackson Park from the Shoreland, in South Shore, in 1936.

That’s probably how Shorelander Ike Bezark’s family held his wake, going by the papers. Bezark, owner and president of a women’s clothing store chain with its flagship store at 20-22 S. State St., died on a trip to Los Angeles in 1931. “The body of Mr. Bezark will arrive at his home in the Shoreland hotel on Tuesday,” noted the Tribune in a short obituary article.

Other Shorelanders died less peacefully, such as William Hill.

William Hill came to the Shoreland with his wife Edna from Somerville, New Jersey. Apart from their time at the Shoreland, all I know about William and Edna is from the 1940 census. We’ll assume William went by “Bill.” He was then 38 and Edna 32, both immigrants from Scotland. Bill had finished college, unusual for the time, and working as a safety engineer. Edna had graduated from high school. Bill reported making $3,000 in 1939—$66,000 in 2023 money. In 1940, the Hills had no children.

Edna and Bill must have been so excited when his boss at Union Carbide and Carbon picked him to attend the1946 National Safety Council convention in downtown Chicago. Did Union Carbide pay for just Bill, or did they spring for Edna’s ticket too?

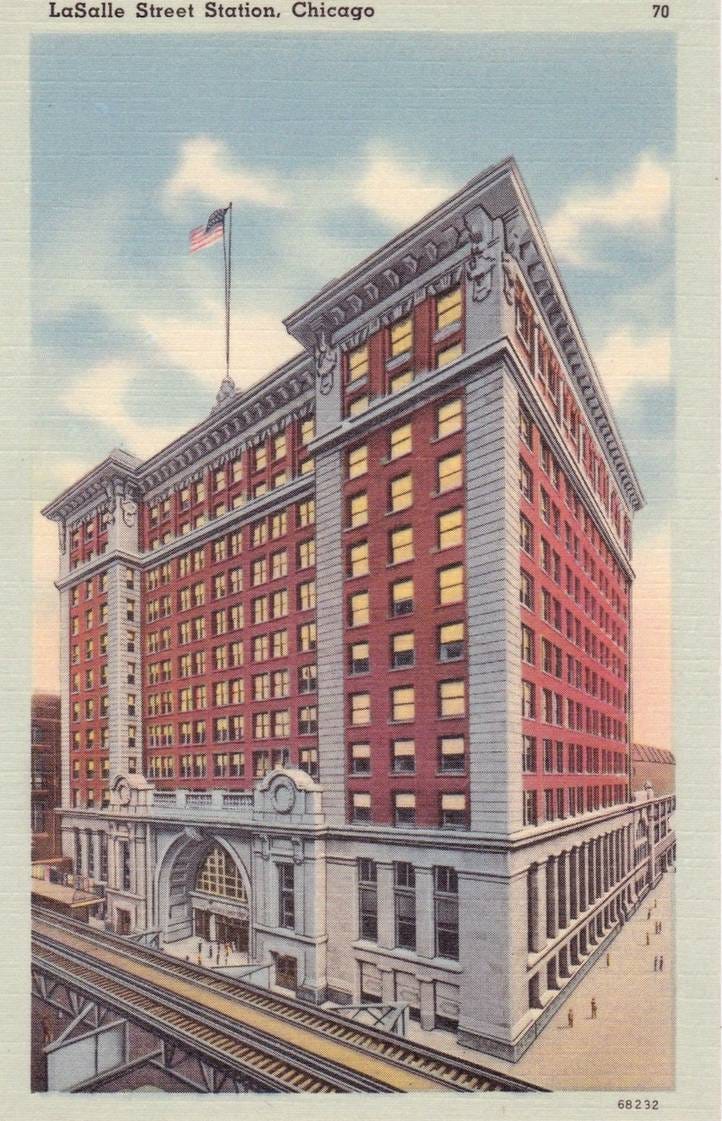

Either way, the Hills surely traveled by train—perhaps the famous 20th Century Limited from New York’s Grand Central to Chicago’s LaSalle Street Station. Here’s the since demolished LaSalle Street Station, circa 1940, where the Hills would have arrived.

Edna and Bill may not have been as glamorous as Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint, but they would have stepped out onto the same platforms you remember from “North by Northwest.”

Here’s a view of La Salle station’s main entrance on Van Buren in 1948. It’s easy to imagine Edna and Bill among these pedestrians, in their late 1940s hats and women’s skirts.

What a view Edna and Bill must have enjoyed from their fifth floor suite in one of the Shoreland’s two wings, their large windows facing east to beautiful Lake Michigan.

The Hills’ New Jersey friends probably warned them about notorious Chicago weather, but that October of 1946 was lovely. Tuesday, October 9, was positively balmy, hitting 72 in the afternoon.

Maybe Edna and Bill dined out in the Loop after convention business, then found a fun nightspot. Night life was back on the upswing after the lean years of World War II. Then they would have caught a cab down Lake Shore Drive to the Shoreland, windows rolled down for the breeze off the lake.

The temperature was just dropping through the 60s when Bill and Edna finally got ready for bed late that night. Bill puttered around in his pajamas while Edna “took off her face” in the bathroom. Edna wouldn’t have been surprised when Bill stuck his head in at the door and said he wanted some fresh air, he was going to open a window—in the Scottish accent they must have had.

“That was the last she saw of him, she said,” the Tribune reported next day. “Hill crashed on the South Shore dr. side of the hotel.”

A coroner’s inquest declared William Hill, 44, an “open death”. He “either fell or jumped”.

Did Bill land on the Shoreland's elegant horseshoe front drive, or the sidewalk along Shore Drive? We don’t know.

I wonder if Bill really could have jumped out of his Shoreland window after telling Edna he wanted to get some fresh air. That would put a much darker spin on the whole story, but I suppose no more unlikely than a safety engineer falling out of a window.

Unfortunately, Bill was not the only Shorelander to die by falling, or jumping, out of a window.

In 1947, Shoreland permanent resident Leonard Moses, 55, jumped from the eighth floor of the Merchandise Mart, leaving a wife and two daughters. He was “overworked, fatigued, and ill” due to his Paragon Hat Co. business, according to his widow.

In 1952, Donald and Lillian Hayseldon checked into the Shoreland so Mrs. Hayseldon, despondent over the recent polio death of her teenage son, could be near her sister in Chicago. Donald told police he was in the bathroom when he heard a screen being removed from one of the suite’s 12th floor windows.

“He said he ran into the room and found his wife climbing out the window,” per the Tribune. “He said he seized her housecoat, but was unable to halt her plunge.”

Elsie Freeman, 65, is the last recorded jumper from the Shoreland in 1960, falling from her 7th floor window in back of the Shoreland onto the roof of a third floor section that projects from the building. She left no note.

The same scene today, minus the fire escapes.

Catch up with Mike Royko in 1972 here. We give you the political and pop culture context to his columns, so you’ll get all the inside jokes.

The Shoreland, 2023

Mac Properties owns the Shoreland now, along with about 99% of Hyde Park’s rental property. Judging from the exterior, the company appears to take decent care of the building.

They do a nice job on the plantings, too.

The wonderful original entrance—which again is a porte cochere, as Max Chavez of Preservation Chicago kindly informed me. It was painted a much lighter color in the early decades, black by the 1950s, light again in the ‘70s, and back to black post-rehab in the early 21st century.

This smaller entrance on the south side, near the front, harkens back to the grand front porte cochere. I wasn’t sure if it qualified too as a porte cochere, but reader JoanP in comments pointed out quite sensibly that a porte cochere is a place where a chauffeur would be able to stand. So no. Still, it’s a nice touch.

A few close ups of the side entrance (porte cochere?) and the southern wall:

Here’s the front southern corner and side entrance in more context.

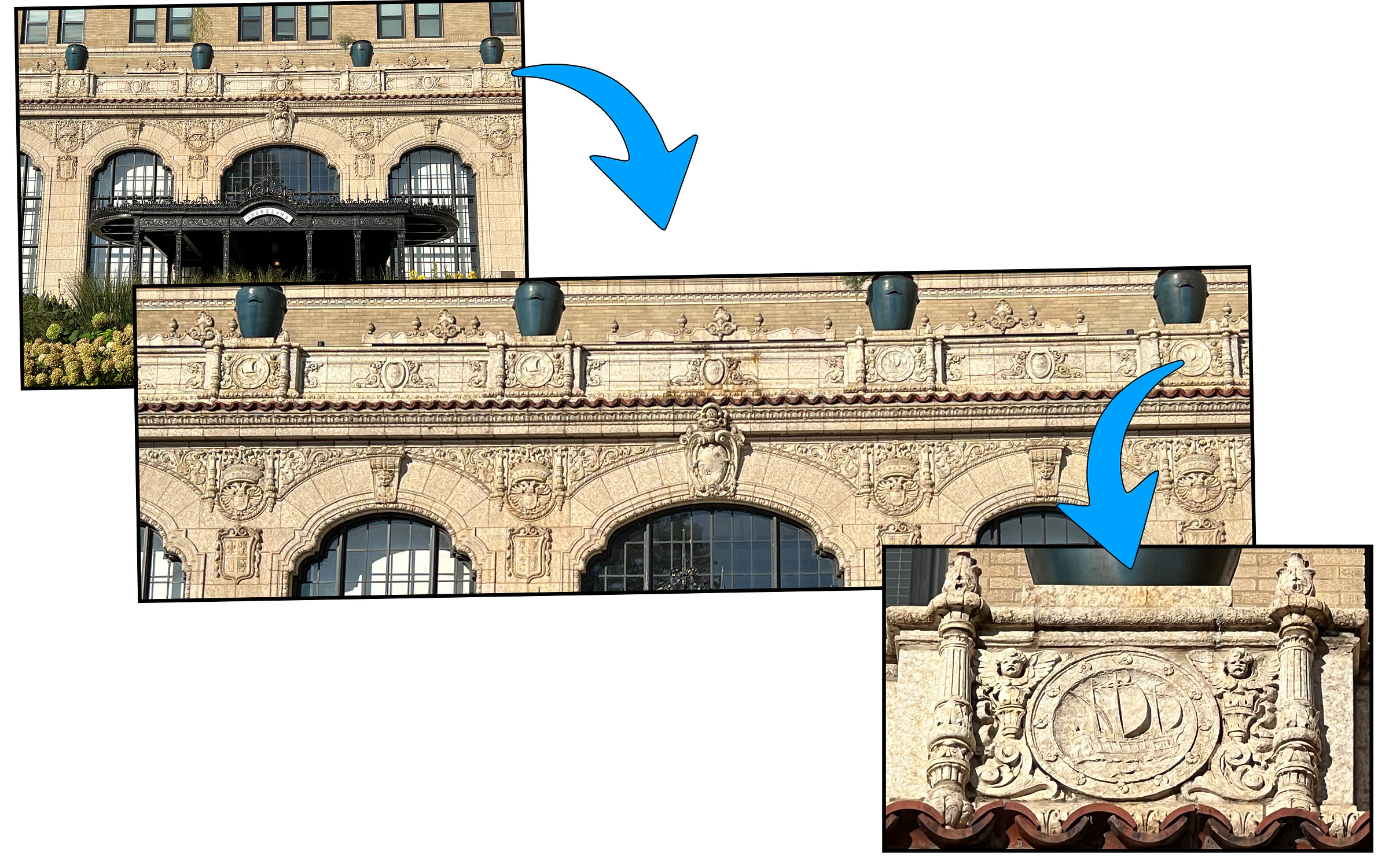

The Shoreland isn’t heavily ornamented, and the brickwork itself is not fancy. Its elegance comes from architect Meyer Fridstein’s overall design—perhaps especially the two-story base clad in what looks like stone, but per the Landmarks Designation report, is actually terra cotta from the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company:

“By concentrating the most elaborate detailing along the base of the building and keeping decoration to a minimum on the floors above, [architect Meyer] Fridstein created a sense of intimacy within the courtyard that minimized the monumental nature of the building.”

There are some particularly interesting spots to note. Here’s the center section roofline, followed by more targeted close ups.

One of two huge terra cotta cartouches fronting the projecting towers on each side of the Shoreland. The Spanish galleon in the center is the Shoreland’s logo, per the city’s Landmark Designation Report…

…which is repeated in the ornamentation on the second floor balcony overlooking the front drive…

…and the arch over the doors leading inside from the south and north wing balconies.

Some close ups of the north wing:

I checked the alley, but all signs of the building’s interesting past were obliterated by the rehab.

The northern side of the Shoreland has this one extra interesting element, presumably a staircase:

And a last bit that my canine companion understandably took an interest in.

Subscriptions are free, so why not give one away?

Shoreland Past & Present

Last, I’m stealing a page from the fabulous website Postcard Past/Present Photo (which I encourage you to visit soon) with two looks at the back of the Shoreland from Everett Avenue. Everett is west across the alley from the old hotel.

The black-and-white picture on the left, via John Chuckman of course, is from 1930, four years after the Shoreland was completed. The one on the right, from 2023. The pictures would mesh better with a 2023 winter view, since the trees in bloom are blocking most of the Shoreland and this courtyard apartment building on the east side of Everett between 54th and 55th.

Here are the two pictures in full:

Two changes to note on the back of the Shoreland.

1. Alas, the big sign is no longer there. I wonder if it was neon?

The fire escapes are gone too, leaving behind only their ghostly imprints.

Next time: Shorelanders—famous, infamous and just plain fun

Subscribe for free to get it straight to your emailbox:

*Leif Erickson Drive

North of the Chicago River, Lake Shore Drive—now DuSable Lake Shore Drive—started out with its now iconic name. South of the river, the lakeside drive originally began at Randolph. Downtown through Grant Park, it was sometimes called “Field Drive,” with “Leif Erickson Drive” starting at 22nd St. and reaching Jackson Park by 1929.

There were perhaps six different spellings for “Erickson,” but either way, Chicagoans commonly called it “the Outer Drive” instead from the get-go. Leif Erickson Drive would hook up with Lake Shore Drive north of the Chicago River via the Outer Drive Bridge in 1937, but it’s unclear exactly when “Leif Erickson” changed its name. The last mention I can find of “Leif Erickson Drive” in any digital archive, no matter how you spell it, is a 1946 Tribune editorial arguing that most Chicagoans wanted one name for the whole drive, and a majority preferred “Lake Shore Drive.” After that, crickets.

It’s bizarre that such a major roadway would undergo an official name change without a single mention in the papers, but there you are. My collection of Chicago maps are mainly from the late 50s and 60s, when the name change has already taken place. I believe it happened between 1946-1950, because I have one street map using 1940 census numbers, but otherwise undated, which uses “Lake Shore Drive” on the South Side.

If you came here from social media or another site section such as THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 or Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today, you may not know this whole odd enterprise is part of the book being serialized here: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

To get new Chicago History Rabbit Holes and other section posts directly to your emailbox, SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE!

As a Hyde Parker, I really enjoyed this article! The Shoreland has a fascinating history. And, no, the side entrance is not a porte-cochère. Portes-cochère are covered spaces under which your coachman (later chauffeur) would drive to allow you to enter a building without being exposed to the elements. Clearly, he couldn't do that at the side entrance.

(Note: found you through Eric Zorn's Picayune-Sentinel, so you can thank him for a new subscriber)