THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972: Nelson Algren makes peace with the Tribute--er, Tribune

Literary Supplement #3

To access all website contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item peeking into newspapers from 1972? Because 1972 is part of the ancient times when everybody read a paper. Everybody, everybody, everybody. Even kids. So Steve Bertolucci, the 10-year-old hero of the novel serialized at this Substack, read the paper too—sometimes just to have something to do. These are some of the stories he read. Follow THIS CRAZY DAY on Twitter: @RoselandChi1972.

Literary Supplement #3

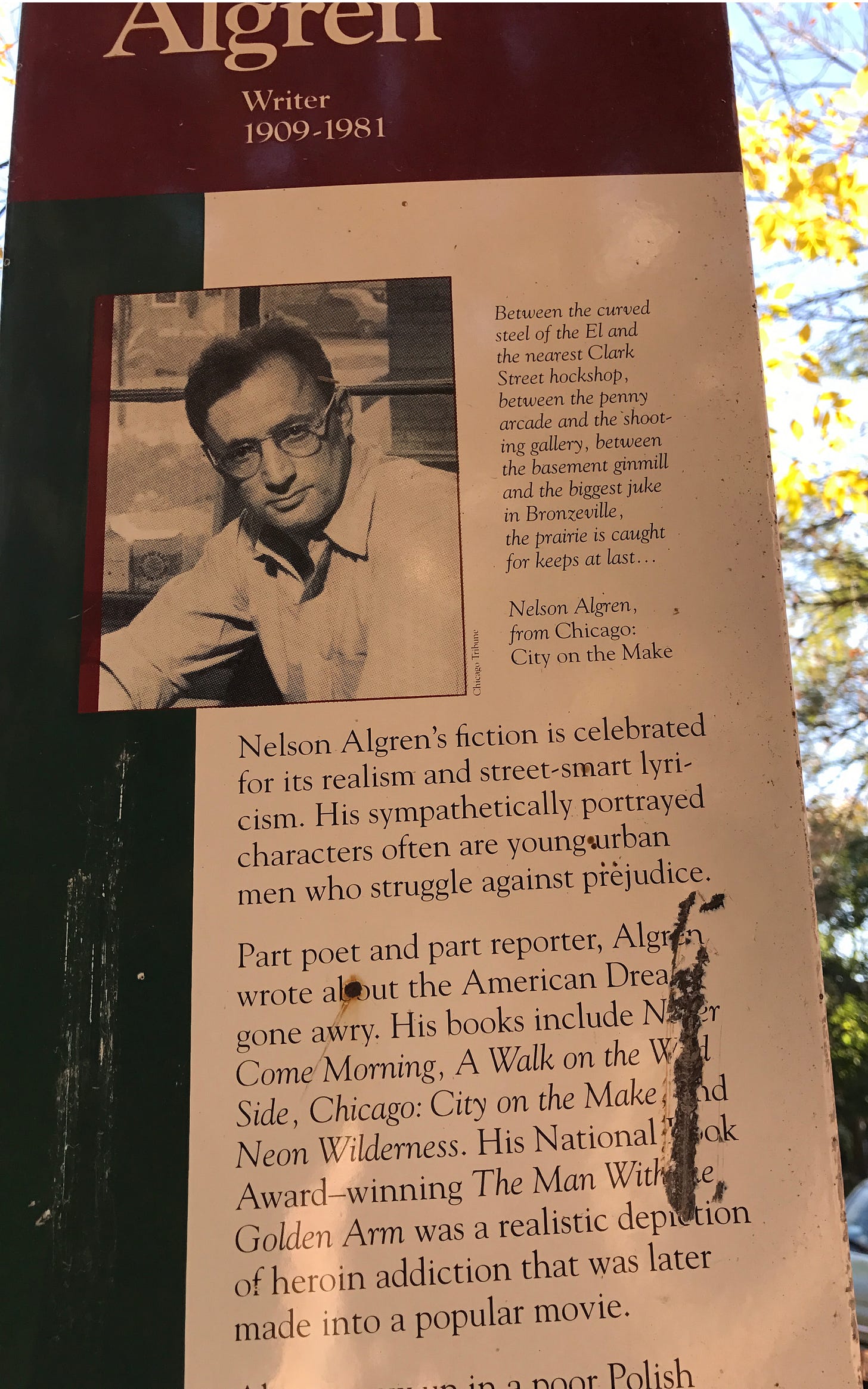

Now that we’ve taken a first peek at two of Chicago’s three biggest 1972 literary stars, we can’t overlook the third, Nelson Algren. If you missed ‘em, see Literary Supplement #1 on Saul Bellow here, and Literary Supplement #2 on Gwendolyn Brooks here, which includes a local Brooks field trip guide.

Nelson Algren was born in 1909 in Detroit, and his Jewish and German/Swedish family soon moved to Chicago. He spent his early years as a White Sox fan in the South Side’s Park Manor neighborhood, staying loyal to the team when the Algrens moved to the North Side’s Albany Park.

Unable to find a journalism job during the Depression after graduating with that degree from the University of Illinois, Algren didn’t stick around Chicago to help his family—who could have used it. As mentioned in Literary Supplement #1, Algren could be a prickly personality, such that Rick Kogan recalled him recently as “an asshole.” Instead of helping at home, Algren rode the rails like millions of other men of that time. Among other things, Algren stole a typewriter in Texas and did a little harrowing jail time there. The experience provided him fictional fodder for a lifetime.

Algren returned to Chicago and joined the city’s literary community, meeting people like Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks and Studs Terkel as he worked for the WPA’s Federal Writer’s Project. He used his travel adventures as the basis for his first book, “Somebody in Boots,” in 1935.

His second novel, “Never Come Morning” (1942), was set in his new home in the Northwest Side’s Polish community. The locals weren’t so crazy about Algren’s penchant for portraying the dregs of their society. Outraged Polish Chicagoans got the book banned from the Chicago Public Library.

Next came a 1947 collection of short stories, “The Neon Wilderness,” then Algren’s “The Man with the Golden Arm.” That 1949 blockbuster won Algren the inaugural National Book Award.

The memorable opening scene, describing Chicago Police Captain Bednar:

The captain never drank. Yet, toward nightfall in that smoke-colored season between Indian summer and December’s first true snow, he would sometimes feel half drunken. He would hang his coat neatly over the back of his chair in the leaden station-house twilight, say he was beat from lack of sleep and lay his head across his arms upon the query-room desk.

Yet it wasn’t the work that wearied him so and his sleep was harassed by more than a smoke-colored rain. The city had filled him with the guilt of others; he was numbed by his charge sheet’s accusations. For twenty years, upon the same scarred desk, he had been recording larceny and arson, sodomy and simony, boosting, hijacking and shootings in sudden affray: blackmail and terrorism, incest and pauperism, embezzlement and horse theft, tampering and procuring, abduction and quackery, adultery and mackery. Till the finger of guilt, pointing so sternly for so long across the query-room blotter, had grown bored with it all at last and turned, capriciously, to touch the the fibers of the dark gray muscle behind the captain’s light gray eyes. So that though by daylight he remained the pursuer there had come nights, this windless first week of December, when he had dreamed he was being pursued.

“The Man with the Golden Arm” soon found its way into the hands of a young American soldier in a tent in Korea —Mike Royko.

Don’t miss Mike Royko 50 Years Ago Today

“A guy in a nearby bunk tossed a paperback at him and said, ‘Here’s a book about Chicago. You want it?’” writes Doug Moe in wonderful “The World of Mike Royko.” “The book was ‘The Man with the Golden Arm’…The cover copy said it was set in a Chicago slum around Division Street. Royko was offended. ‘Slum?’ he thought. ‘That’s no slum. That’s my neighborhood.’”

Moe continues: “The book knocked [Royko] out. ‘Here was somebody named Nelson Algren writing about Division Street and Milwaukee Avenue, and the dope heads and boozers and the card hustlers. The kind of broken people Algren liked to describe as responding to the city’s brawny slogan ‘I Will’ with a painful: ‘But What If I Can’t?’”

Not long after Royko began writing his Daily News column in 1963, Richard Ciccone recounts in his also wonderful Royko bio, “A Life in Print,” Nelson Algren called his pal Studs Terkel: “Have you seen this guy Royko?” he asked Studs. “He tells it with all the warts and the carbuncles, and he hits hard but he’s pretty funny.”

“That was something coming from Algren,” Studs told Ciccone. “He hated newspaper people.”

Royko and Algren would strike up a life long friendship. As Doug Moe relates, Algren dedicated a new edition of “The Neon Wilderness” to Royko, who had pronounced it his favorite Algren work.

“In May of 1981, David Royko came to visit his father at his home and walked in to find him crying,” Doug Moe writes in his Royko bio. “‘He was just sobbing and I was concerned. This was something you never saw. I asked him what was wrong and he didn’t really answer.’” It turned out Nelson Algren had just died.

Algren and feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir shared a wildly romantic but ill-fated mid 20th century romance. He called her “Frenchie,” and she was buried wearing the ring he gave her. They are unbelievably cute in photographs.

Algren’s celebrated poetic quasi-history and love-hate letter to his hometown, “Chicago: City on the Make,” was published in 1951 after appearing in truncated form in Holiday magazine. By many accounts, it’s quoted as often now as Carl Sandburg’s poem “Chicago.” Sandburg immortalized Chicago as the “City of the Big Shoulders,” while Algren imagined the city as a lover with a broken nose.

The full quote:

Yet once you’ve come to be part of this particular patch, you’ll never love another. Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may well find lovelier lovelies.

But never a lovely so real.

A few more notable quotes:

It isn’t hard to love a town for its greater and its lesser towers, its pleasant parks or its flashing ballet. Or for its broad and bending boulevards, where the continuous headlights follow, one dark driver after the next, one swift car after another, all night, all night and all night. But you never truly love it till you can love its alleys too. Where the bright and morning faces of old familiar friends now wear the anxious midnight eyes of strangers a long way from home.

and

Every day is D-day under the El.

and

Yet on nights when, under all the arc-lamps, the little men of the rain come running, you’ll know at last that, long long ago, something went wrong between St. Columbanus and North Troy Street. And Chicago divided your heart.

Leaving you loving the joint for keeps.

Yet knowing it never can love you back. *

* An “arc-lamp” is an older term for electric streetlamp. Algren was raised Catholic, and St. Columbanus was his home parish in the South Side’s Park Manor. North Troy was the North Side street the family moved to later. “City on the Make” isn’t the easiest book to decipher. I highly recommend the edition annotated by David Schmittgens and Bill Savage. That edition also gets you a great introduction by Studs Terkel.

The iconic ending:

The Pottawattomies were much too square. They left nothing behind but their dirty river. While we shall leave, for remembrance, one rusty iron heart. The city's rusty heart, that holds both the hustler and the square Takes them both and holds them there. For keeps and a single day.

But in 1972, Nelson Algren’s career was mostly behind him. He considered himself more a journalist by then, making his living mainly with free lance articles and book reviews. His most recent novel at the time, “A Walk on the Wild Side” from 1956, was nearly 20 years behind him. (“The Devil’s Stocking” would be published posthumously.)

In 1972, Algren would publish one more well-received book in his lifetime: “The Last Carousel,” a varied collection of previous writings released in 1973. But the book wouldn’t sell well, and Algren would famously leave Chicago in 1975 after holding a rummage sale in his third floor apartment at 1958 W. Evergreen. As former Tribune reporter Mary Wisniewski notes in her terrific recent Algren biography, “Algren,” all of his books were out of print by then—except the paperback edition of “Carousel.”

Above, Algren’s long-time home, the third floor apartment at 1958 W. Evergreen. Below, the alley. I assume he loved the alley just as much.

For good measure, here’s his childhood alley in Park Manor, too:

Here are two portions, badly photographed, of the Tribune-sponsored “Marker of Distinction” in front of the Evergreen building:

When Algren left Chicago, he moved to Paterson, New Jersey to work on a book about Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, hoping to make it big in the burgeoning true crime genre. But the book never sold, and he ended up fictionalizing the story in the ill-conceived “The Devil’s Stocking,” which no one has anything good to say about. He never saw that work in print.

If you were reading the Daily News, the Sun-Times, the Defender or Chicago Today in 1972, you might not remember Nelson Algren was still in town, unless you saw one of his brief mentions in the Daily News gossip columns by Bob Herguth and Jon and Abra Anderson. (You can run through some of those mentions, along with Saul Bellow’s, here.)

But miraculously, after no coverage in the Tribune since 1968, Nelson Algren was suddenly all over the 1972 Trib.

The Tribune? That’s a bit curious, since Nelson Algren was “a part of the Communist movement and probably a party member sometime during the 1930s,” as Wisniewski puts it in her biography. Algren wasn’t a very good Communist. He didn’t really do much for the party. But like nearly every writer who was anybody at the time, and everybody who wasn’t, Algren joined the Communist-associated League of American Writers and signed the 1938 “Statement by American Progressives,” Wisniewski relates. The statement criticized “premature condemnations of the Moscow show trial. These were the trials Stalin used to kill off his political enemies.”

Not surprisingly, Algren didn’t get along with party authorities, yet he also signed what was called the May Day letter in 1948, “in solidarity with Soviet writers and against anti-Soviet politics in the United States,” writes Wisniewski. That earned him an FBI file. In 1952, Algren worked prominently in the movement to clear Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, serving as honorary chairman of the Chicago Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg Case.

None of that would have endeared Algren to anybody at the Tribune. Recall from our Chicago Newspapers Circa 1972 chapter that the early and mid-20th century Tribune was the wood pulp personification of owner-publisher Colonel Robert McCormick.

The Colonel/Tribune was so ferociously conservative, he called President Herbert Hoover “the greatest state socialist in history.” Naturally, he considered Franklin D. Roosevelt a Communist—“Although I don’t know if he carried a card,” the Colonel told a reporter in 1951.

So Algren was never any lover of the Tribune. This was common outside the conservative middle and upper classes of Chicago. Here’s a great observation by long-time Tribune reporter Ron Grossman about newspapers and his own household in early and mid-20th century Chicago:

As Mary Wisniewski notes in her bio, Algren mocked the Tribune in his first novel, calling it “The Tribute.” In “City on the Make,” he referred to Colonel McCormick as “the Only-one-on-Earth, the inventor of modern warfare, our very own dime-store Napoleon, Colonel McGooseneck.”

Then, in an afterword to a 1961 edition of “City on the Make,” Algren wrote:

For there is no room left for the serious writer to stand up in old seesaw Yahoo Chicago….The American spirit has discovered its manliest voices, as well as its meanest, here.

At its manliest: Gene Debs saying “While there is a soul in prison I am not free.”

At its meanest: see the editorial page of the Chicago Tribune any morning of the week. Better yet, take a fast glance at the front page cartoon and walk away: you’ve just saved seven cents.

The Tribune began running full-color editorial cartoons smack in the middle of the front page by 1932. The cartoons were inevitably and savagely anti-FDR and anti-Communist. The 1962 cartoon below shows a farmer smoking with FDR’s cigarette holder, off to slay capitalism embodied in the goose that lays golden eggs—even though FDR had died in 1945, and the Colonel died in 1955.

The Tribune kept up its front page editorial cartoons, in the same vein, until 1970. The paper began shaking off the Colonel with the ascension of Clayton Kirkpatrick as editor in 1969. Even so, the Tribune reported on March 10, 1972 that the then-current scourge of airline hijackings were “regarded by security authorities as opening moves in a broad scale war against the United States commercial air system….Analysis suggests the assault is being coordinated by some central group.” A “British intelligence source,” per the Trib, said “[C]lasses of air guerillas have been graduating in Cuba and dispatched around the world with the goal in mind of disrupting the non-Communist air transportation systems.” No one else reported this sensational story, and the Tribune never mentioned it again.

That said, to look at the Tribune archives, Nelson Algren wasn’t the favorite punching bag you would expect. Starting with Algren’s first novel, the Trib dutifully runs bits on his appearances and speaking engagements. There are the occasional jabs, such as when Kelsey Guilfoil reviewed “Cross Section 1947,” a short story collection, and attacked everybody in it for their bleak outlook that “sounds a note of hysteria, almost of madness.” Algren actually got off easy compared to some other contributors to that book, criticized simply for writing about “some skid row characters.”

The Trib’s Frederic Babcock recommended “The Man with the Golden Arm” as one of five books to read in 1949, and regular Trib literary columnist Fanny Butcher attended Algren’s book party at Stuart Brent’s: “Bitterness is shot thru with tacit tenderness in what Nelson Algren writes,” Butcher ruminated. “Nothing escapes him and when what he has seen is translated onto the printed page it is a truly literal translation of life…Perhaps that is why Ernest Hemingway named him song the great contemporary American novelists.”

True, the Tribune didn’t initially embrace “City on the Make.” Fanny Butcher from December 9, 1951:

And the Trib review by Alfred C. Ames, October 21, 1951:

“Algren’s publisher says: ‘This will be the gift book in Chicago for years…published in good time for the fall Christmas market.’ Gift books characteristically are pleasant, meant to please the recipient and to be something one likes to have around. This one is thoroly unpleasant, unlikely to please any who are not masochists, and is definitely an ugly, highly scented object….A more distorted, partial, unenviable slant was never taken by a man pretending to cover the Chicago story. Definitely not a gift book.”

But really, other than those reviews, Algren seems to get a fair shake in the Tribune, even regular mentions in Herb Lyon’s Tower Ticker column through the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Still, you really wouldn’t expect Nelson Algren to suddenly jump onto the Tribune’s lap in 1972. If Nelson Algren was going to start regularly publishing in one of Chicago’s newspapers, why not the Daily News, where his pal Mike Royko worked?

He must have met somebody from the Trib at a party, is my guess, to facilitate his entrance into the Tower freelance fold. Mary Wisniewski’s bio quotes Trib book editor John Blades, “a longtime fan of Algren’s who was excited to have him start writing reviews and occasional feature articles for a paper that had given him some hard criticism in the past.”

So maybe he ran into John Blades somewhere? The important thing is, we here at TCD1972 have a terrific amount of 1972 Algren material to share with you in coming Literary Supplements.

Today, having gone on long enough, we simply present an excerpt of Nelson Algren poems from the October 8, 1972 Chicago Tribune Magazine.

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

In the middle of a book of Thomas Sowell essays, will have to see if my digital library has any Algren books. I read Bellow's Henderson the Rain King over 40 years ago for a class in college. I remember nothing about it but the name, but that was the late 70's and most of college was a blur.