Mike Royko 50+/- Years Ago Today: The Ascent of Royko

The Life and Death of High-Rise Man, Part One

To access all site contents, click HERE.

This is Part One of a seven-part series on Mike Royko’s High-Rise Man columns mocking wealthy lakefront Chicagoans, and the life that led him to write those columns. Click here for links to the rest of the series.

The Life and Death of High-Rise Man:

Part One - The Ascent of Royko

When you think of Mike Royko, where do you picture him?

Perhaps in his natural element, smoking and working at a typewriter….

…or drinking at the Billy Goat.

That makes sense. Royko worked long hours. The pressure of churning out five columns per week guaranteed to be read, quoted and potentially cursed by the entire city exacted a great toll. After he turned the column in, sometimes late at night, Royko often repaired to the nearby Goat. Sometimes too often, and for too long, by many accounts.

Royko also combined writing and bars by writing about bars—like helping out in his dad’s tavern as a teenager, plus earlier Saturday afternoons with Grampa Bielski, who babysat little Mickey by strolling to the closest tavern on Division. There were too many bugs in nearby Wicker Park, Grandpa Bielski explained.

For Younger Readers: Bars were mostly called “taverns” in 1930s and 40s Chicago, and “apartments” were “flats.” Extra credit for Older Readers: Tell us in Comments when and why both terms changed in Chicago by the 1980s, or maybe ‘70s. If nobody knows, I’ll investigate for a Chicago History Rabbit Hole.

Besides Machine politics, Royko often wrote about growing up in the still largely Polish Milwaukee Avenue corridor with pals like Slats Grobnik. When Chicago author Bill Brashler hung out with Royko for a terrific 1979 Esquire profile, Royko sat at the counter “at Mary’s corner restaurant on Haddon and California” and ordered a dozen pierogi—“no plum, no chicken.”

So you can picture Mike Royko anywhere on or near Milwaukee Avenue.

But you probably do not picture Mike Royko lounging about a big condo on the lakefront.

Yet this is precisely where Mike Royko moved in 1981: 3300 N. Lake Shore Drive*, with its stunning views of Belmont Harbor.

Even though Mike had been hilariously, mercilessly insulting wealthy North Side lakefront residents for years, branding them with the moniker “High-Rise Man.”

According to the website of Fitzgerald Associates Architects, Royko’s gorgeous pre-World War II condo building is the Sheridan-Aldine Apartments, originally owned by the Edith Rockefeller McCormick Trust.

Edith, daughter of John D., lived there “for a time”.

La-dee-da-da! Mike Royko living in a building that once contained a Rockefeller?

Yes. Royko moved into a four-bedroom, sixth floor corner unit two years after the tragically young death of his first wife, Carol. He stayed until 1985, returning to the Northwest Side shortly after his marriage to Judy Royko. As Dennis Rodkin recently reported in Crain’s Chicago Business, the condo is currently on the market again, after “an extensive rehab,” for $1.4 million.

Here’s a lovely shot of the spruced-up living room by VHT Studios, used for the real estate listings. You can see all 34 photos at the Zillow listing here.

Judy Royko and Mike’s oldest son, David Royko, both generously talked with me about Mike’s time on Lake Shore Drive, which is particularly fascinating for we fans who love him.

But first we must ask, how did Mike get there?

I mean that both literally and metaphorically.

Where exactly did Mike live on his way to Lake Shore Drive? We all carry so much of our former homes with us, as if they lived in us rather than the other way around.

And what sort of life, in those homes, led Mike Royko to mock wealthy lakefront Chicagoans in 15 columns spanning almost 20 years?

Let’s take a look. Along the way, some classic Royko columns emerge. Here’s a rundown on the rest of the series, then onward to Part One.

Part Two: The Birth of High-Rise Man

Mike discovers a new species of privileged Chicagoans. Columns ensue, including two all-time Royko classics.

Part Three: Mike and Walter and Insults, Oh My!

Mike’s High-Rise Man column on November 5, 1981 slams headlong into his lengthy feud with top Chicago TV news anchor and commentator Walter Jacobson. Here’s an initial look at Walter—and Mike and Walter—so the November 5 column will make some sort of sense to you.

Mike’s November 5, 1981 column appears to be a very hot take on the independent lakefront liberals of the 43rd Ward, especially Ald. Marty Oberman and his constituent Walter Jacobson. But it’s really about Richard M. Daley’s successful 1980 campaign to move up from state senator to Cook County State’s Attorney. We’ll give you a backgrounder on the politics and examine the sizzling November 5 column. Careful not to burn your fingers.

Part Five: The House on Sioux Leads to Lake Shore Drive Mike and his first wife Carol moved their young family into a darling house in Edgebrook. That house encapsulates why Mike would always identify with poor and working class Chicagoans, and scoff at wealthy lakefront residents as “High-Rise Man.” Mike’s departure from Sioux Avenue shows us what always made him tick—and finally drove him to a big condo on Lake Shore Drive.

Walter Jacobson struck back soon after Mike’s November 5, 1981 column, instigating a monumental front-page Royko High-Rise Man column on November 22 that doubles as a 1980s Chicago time capsule—and essentially ended the High-Rise Man concept. Here, we prepare for that moment of truth by examining how the paths of Mike and Walter crossed and re-crossed through the middle decades of the 20th century—and then observe their biggest collision.

Part Seven: The Last High-Rise Man [Coming]

Because there’s so much fascinating material to cover in Part Six leading up to Mike’s November 22, 1981 column answering Walter Jacobson, that 1980s time capsule of a column gets its own post here.

High-Rise Man Addendum: Bill Granger Weighs In [Coming]

A few months after Mike and Walter’s dust-up, Tribune columnist Bill Granger revisited the issue in his own indelible way. To Granger, the question is: Does your past world disappear? You know what Faulkner would say. Granger covers this age-old debate from a Chicago perspective.

*3300 N. Lake Shore Drive: Lake Shore Drive was renamed “Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable Lake Shore Drive” in 2021—but only for the Outer Drive, not the Inner Drive. Hat tip to reader Greasy Thumb Guzik for reminding me. Corrections always appreciated!

The Ascent of Royko

In which we trace the evolution of Mike Royko through his homes

“From childhood on, I never lived more than staggering distance from Milwaukee Ave., and thought I never would,” Mike wrote in 1981.

I see discrepancies in various sources about precisely where the Roykos lived, starting with Mike’s 1932 birth. Yet Milwaukee Avenue as the Royko lodestar remains accurate for nearly all of Mike’s first 40 years, regardless of which possible addresses are correct.

Precise early addresses are educated guesses, because relatives who could clear up questions have passed away, and living friends, relatives and biographer Doug Moe (“The World of Mike Royko”) couldn’t tell me—at least not yet. I’ll continue asking anyone I can and update if possible.

For now, we’re left with some competing addresses, Chicago phonebooks, and the U.S. census. I’ve done what I could without making a second career out of it. Here we go:

Mike’s parents briefly divorced after having two daughters, Eleanor and Dorothy; then remarried and added Mike and younger brother Bob to the family. In “Royko: A Life in Print,” deceased biographer Richard Ciccone, who spoke to both of Royko’s sisters, writes that the reunited Roykos moved into a basement flat at the northwest corner of Potomac and Wolcott in time to welcome baby Mickey, as he was then called.

Odd, because Royko specifically called himself first “Bungalow Baby,” and later “Basement Flat Child.”

1266 N. Wolcott, still standing in 2023, is steps from Milwaukee Avenue. Check. But it isn’t a bungalow, and it also doesn’t look like it ever had a basement flat. Hm.

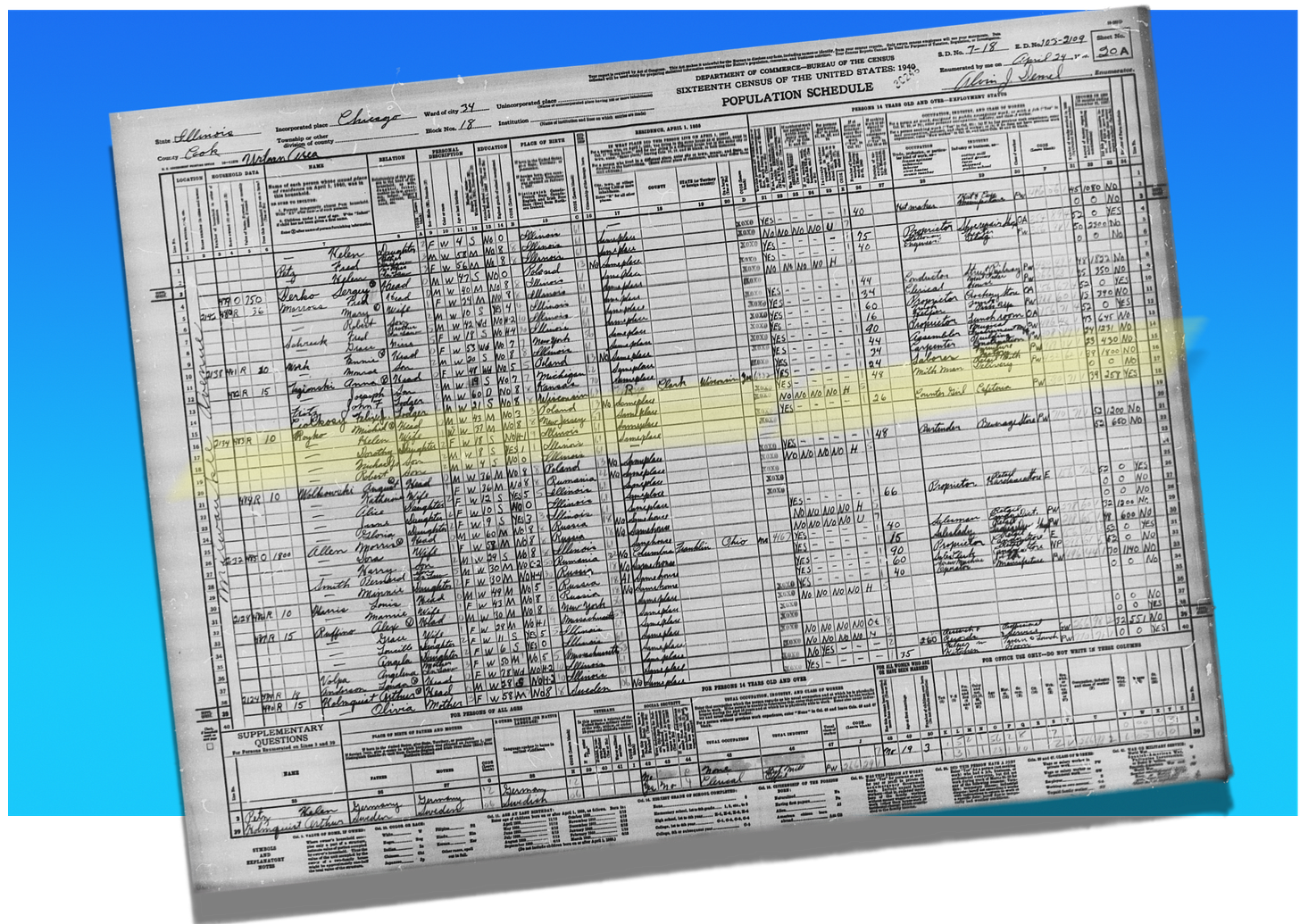

The Chicago phonebook doesn’t answer this question, because the Roykos were never listed—not so unusual in the 1930s and ‘40’s when many people couldn’t afford their own phone. The closest official record of the family’s whereabouts at Mike’s birth is the U.S. census for 1930, when his temporarily divorced mother lived as “head of household” in a courtyard apartment building at 3300 W. Schubert, just off Milwaukee.

Was it a basement flat? The census doesn’t tell us. It would make sense, though, for a single mom with two small children in the middle of the Depression.

Perhaps Royko had it backwards, and he started out in a basement flat—on Schubert. Maybe the reconciled Royko family was still there in 1932 when Mike came along.

It’s as good a place to start as any.

Then, perhaps the Roykos moved to 1266 N. Wolcott when Mike was old enough for his outings with Grampa Bielski. It’s not a bungalow, but Royko probably used that term for any modest single-family home. Two blocks north of Division, the location almost precisely fits Royko’s geographical description of those Saturday afternoons with Grampa Bielski: “We never walked far. Only one block up Wolcott Avenue to the nearest tavern on Division Street.” (I say “almost” because I expect a Chicagoan to mean “north” when using the term “one block up,” while Division is two blocks south of this location.)

In between, apparently the Roykos lived at 851 N. Damen in 1934—at least that’s what Mike’s dad told the Daily News that year after getting held up on his way home from a party.

I’m wondering what the heck he was doing with $17 in his pockets in the middle of the Depression. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation calculator, that’s $400 in 2024. While Mike Sr. was out partying, Helen and their three kids were presumably asleep at 851 N. Damen, the middle building below.

According to Ciccone’s bio, Royko’s family opened the Blue Sky Lounge in 1938—commonly identified as 2122 N. Milwaukee—with Mike Royko Sr.’s cousin Gus. Doug Moe’s bio puts it in 1935. All accounts, including Mike’s, are that the family lived in a flat upstairs from the bar. Royko called himself “Flat Above A Tavern Youth” for these years.

Mike’s sister Dorothy told Richard Ciccone that “the apartment was crowded and violent” after Gus moved in with three daughters and his wife, who Gus frequently beat up.

Mike Sr. and Gus both drank too much, according to Dorothy. Then Mike Sr. began fooling around with his future second wife, leaving the family after he kicked Royko’s mother so hard he broke her ribs.

The Blue Sky Lounge was over.

Don’t forget to dive down a Chicago History Rabbit Hole!

A tumultuous family life wasn’t unusual in poor first-generation immigrant families, of course. According to both Royko biographies, Mike Royko Sr.—originally Mikhail—was born in a potato field near Lvov, while his probably-Polish mother labored both internally and externally.

“I cut the cord, put him in my apron, and took him to the house and cleaned him up and put him on the bed,” Ciccone quotes Mike’s grandmother telling her grandchildren. “Then I went back to pick potatoes.”

After five-year-old Mikhail’s father died, his mother left him and his siblings at an aunt’s farm to seek work in America. The Royko kids had to fight their cousins for food. Four years later, Mikhail joined his mother on Chicago’s South Side and started work right off, doing odd jobs at steel mills.

Rough upbringings often lead to rough adult years, which lead in turn to rough upbringings for the next generation. So it was for the Roykos. Still, young Mickey’s older sisters clearly doted on him.

“I adored him,” Eleanor told biographer Doug Moe. “He was cute and he was smart. I was very proud of how smart he was.”

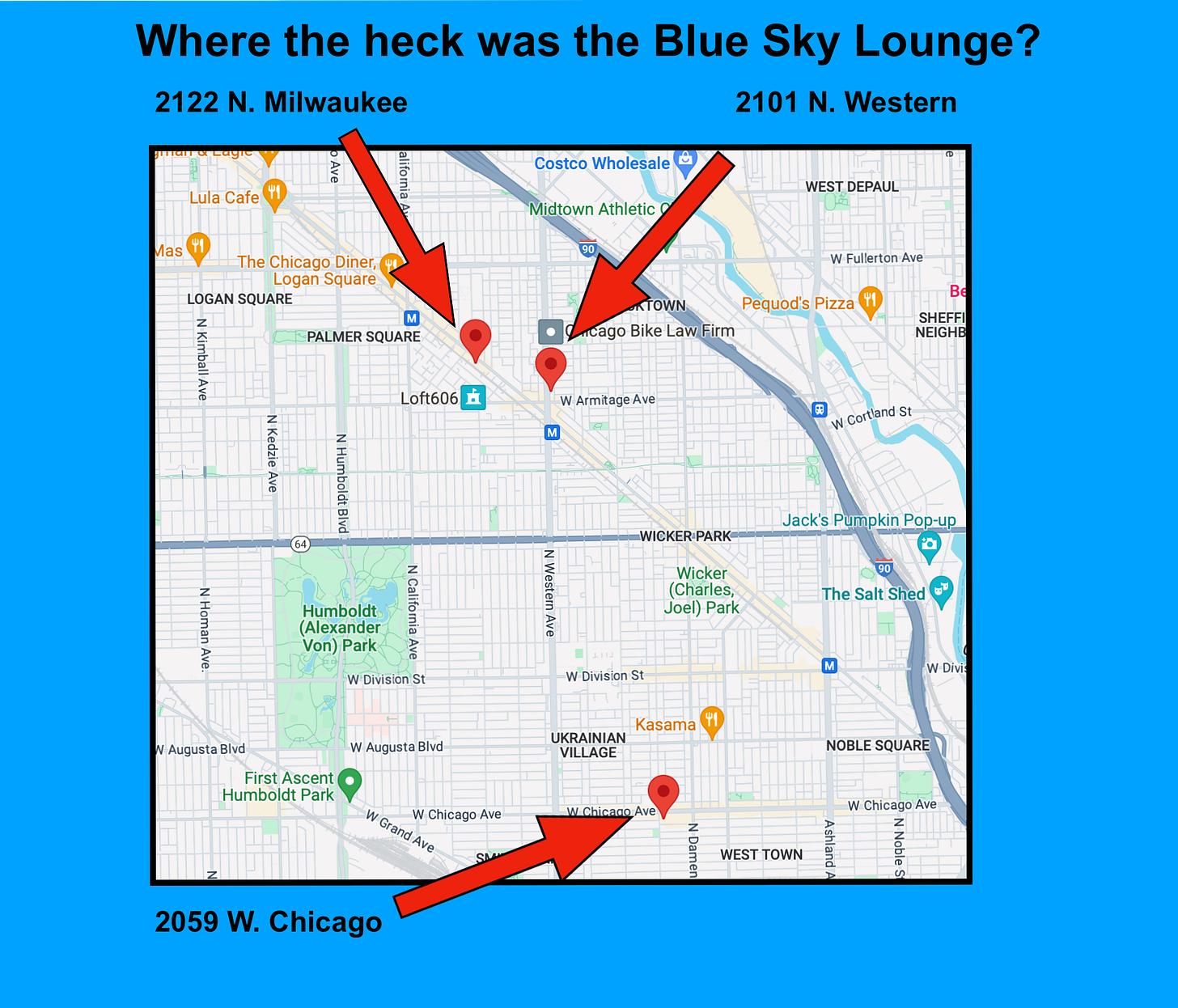

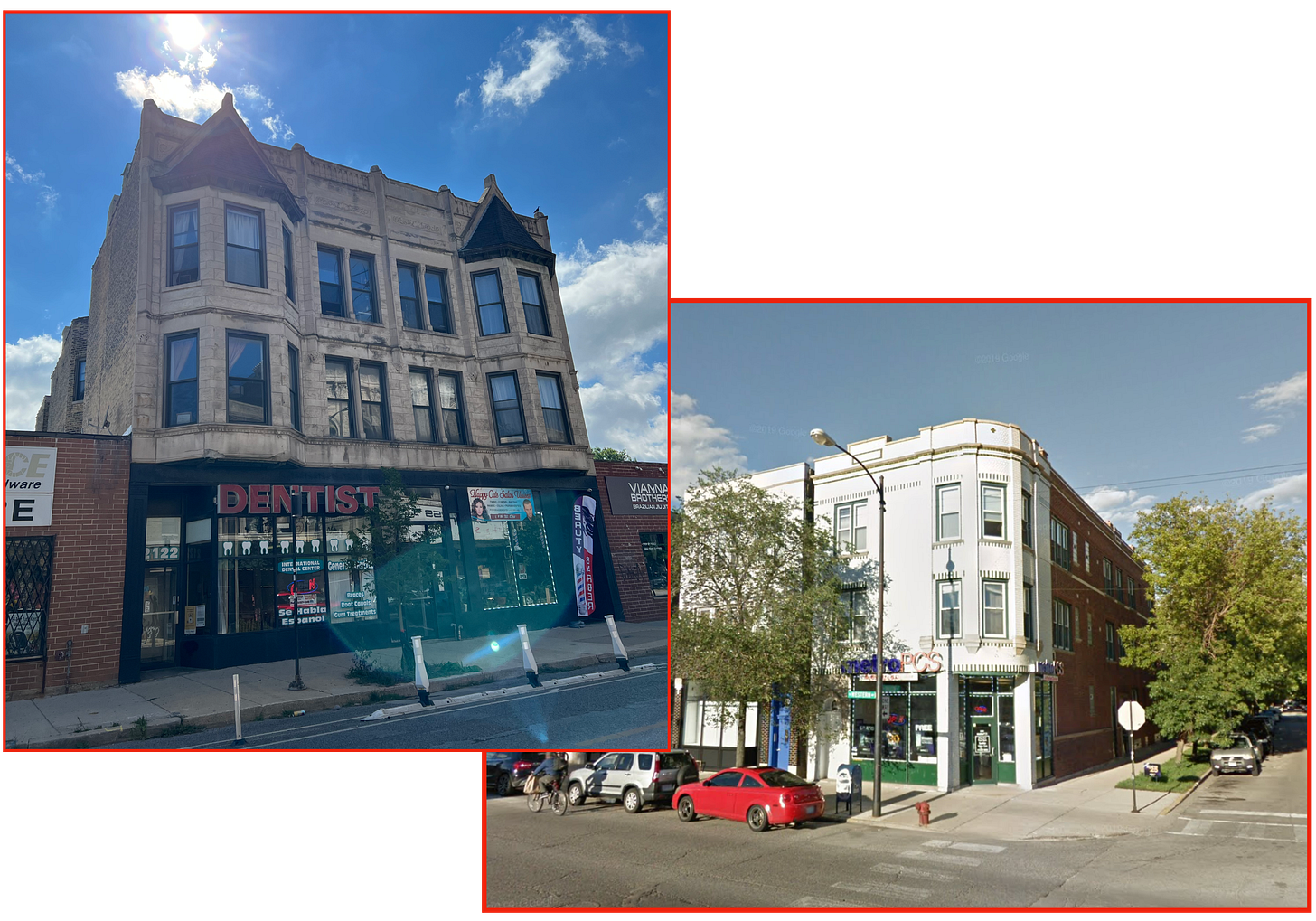

No one says what year the Royko’s Blue Sky tavern ended, but more vexingly, where was it? Nearly all sources—including both biographies—say the bar was here, at 2122 N. Milwaukee:

Yet there is no Blue Sky tavern at 2122 N. Milwaukee in any 1930s or 40s phonebook. Instead, there’s a Blue Sky Inn at 2101 N. Western, a few blocks east of the Milwaukee address, which pops up in the 1937 phonebook along with a Blue Sky Tavern at 2502 S. Wentworth. We can rule out Wentworth. The Western site, though, is basically the right area and time.

The Blue Sky Inn on Western remains the only area tavern using that name until 1940, when a rival Blue Sky Tavern appears at 2059 W. Chicago, at Hoyne. (Another one pops up at 4806 W. Hutchinson, completely out of the Royko ballpark.)

We can also rule out Chicago Avenue—it’s a tad too late and south. One more “Blue Sky Lounge” appears in 1948 at 1450 N. Western—way too late for the Roykos.

That leaves either 2101 N. Western, or the widely cited 2122 N. Milwaukee address.

The case for Western Avenue: Why would the Roykos open a bar on Milwaukee using the same name as an established place just a few blocks away?

And who runs a mid 20th century bar you can’t find in the phonebook?

TPC: The Phone Company

That’s a question we need to answer for Younger and Future Readers, who may be wondering why the phonebook is so important. Or wondering what a phonebook is.

Younger and Future Readers, you won’t remember when the AT&T corporation (American Telephone & Telegraph) controlled nearly all telephone service in the entire country. The Justice Department broke up the monopoly with an antitrust lawsuit resulting in a 1982 consent decree. AT&T was the original giant, evil, all-powerful corporation secretly controlling society. After all, it knew where everybody lived, by definition.

AT&T was known universally as simply “the phone company,” since there was only one. The phone company and its power is ingeniously memorialized in the brilliant 1967 film “The President’s Analyst”—second only to “Dr. Strangelove” as a prescient 1960s dark comedy.

One phone company to rule them all, and one phone book per community to list everyone who could afford a phone. Listing in the phonebook was free. You had to opt out, which nobody would think to do unless they were on the lam. I tried to get my number unlisted in the ‘80s after I started working in newspapers, and the phone company just ignored me. The phone company did what it wanted, because it was the phone company.

People valued that phonebook listing. With no internet, the phonebook was often the only way to find anybody without a private detective. Single women in those days might be concerned about listing themselves. Instead of requesting an unlisted number, they’d use an initial rather than their first name. The logic was questionable since everybody knew a first initial meant a single woman. Still, better to maybe attract a stalker than miss a phone call.

As we’ve seen, poorer families like the Roykos couldn’t afford a phone, and hence didn’t have a phonebook listing. But a business would without fail have a phone, and a listing. The Yellow Pages, a phonebook just for businesses organized by business type and printed on yellow paper, charged for listings. Some modest businesses might skip a Yellow Pages paid listing, but they’d never skip the free “white pages” phonebook listing.

Don’t think a tavern didn’t need a phone.

“I just remember Mike making jokes about the phone ringing and wives looking for their husbands!” Judy Royko laughed when I asked her about the Blue Sky’s location.

Back to Mike

That’s why I suspect the Royko’s “Blue Sky Lounge” at 2122 N. Milwaukee may have really been the Blue Sky Inn at 2101 N. Western, seen below via Google Streetview in 2014…

….although to complicate things even further, according to the 1940 census, during the Blue Sky years the Roykos lived at 2134 N. Milwaukee. That’s not 2122, but it’s also not on Western.

2134 N. Milwaukee is now a small parking lot between two one-story storefronts. No matter what was there, if you go by the phonebook, it didn’t house a Blue Sky Lounge.

As I mentioned in Chapter One of the novel central to this Substack, both the most ordinary and cataclysmic events in our lives are often colored by perception in ways distinctly at odds with reality. People’s memories can just be flat-out nuts. So. There was no Blue Sky Lounge at 2122 N. Milwaukee or at 2134 N. Milwaukee, per the phonebook. But according to the census, the Roykos didn’t live at 2101 N. Western, where there was a Blue Sky Inn.

Then how did the Roykos live upstairs from the Blue Sky Lounge?

They could have lived above the Blue Sky Lounge at 2101 N. Western, but moved before the 1940 census. Except that several sources put the Roykos on Armitage by the time young Mickey was in second grade, attending the nearby Salmon P. Chase grammar school on Point St.

And just to drive you even crazier, Doug Moe’s “The World of Mike Royko” includes one small photo of the Roykos in front of a building identified as “the second Blue Sky Lounge” on Armitage in 1940. That’s Mike leaning against the building, far right.

But according to the phonebook, there was no Blue Sky Lounge on Armitage.

Doug Moe didn’t remember any details to explain that caption when I checked with him. Bill Brashler also mentions the Royko tavern location as Armitage and Point St. in his 1979 Esquire profile—and Brashler drove around the neighborhood with Royko. I still hope to get in touch with Brashler and update this post with any new information from him.

Veteran media columnist Robert Feder read this post and pointed me to a 1993 profile of Royko in The Washington Post by media critic Howard Kurtz—thanks Rob! Kurtz makes at least one definite error in recounting Royko’s history, but he mentions a Blue Sky Lounge on Armitage Avenue and most importantly, he gives an address: 2643 W. Armitage. That’s it, the brick two-story on the left.

Kurtz writes his profile as if he started the day with Royko at the Goat, then drove around the old neighborhood before ending up at Royko’s home at that time in Winnetka. And this building is in exactly the right place, across the street from Point St.

Whether the Roykos lived above a bar at 2122 N. Milwaukee or at 2101 N. Western, and maybe later at 2643 W. Armitage, you can now picture the sort of place they lived, and the sort of life they lived there.

Let’s assume the Roykos moved to 2643 W. Armitage or somewhere near Armitage and Point, but right after the 1940 census. Ciccone describes Mike living on Armitage by then, practically across the street from Salmon P. Chase School, though never clarifying whether this was still above the family bar.

To help you place it, Armitage and Point St. puts the Roykos just a tad west of Milwaukee and Western, meaning a tad west of Margie’s Candies. Margie’s would have been there for the Roykos too, because it opened in 1921.

Either way, little Mickey Royko started attending Salmon Chase, and he soon met cute little Carol Duckman. Carol’s family lived just up Point St. from the school, on Francis Place.

“We met when she was 6 and I was 9,” wrote Royko in his first column after Carol’s death. “Same neighborhood street. Same grammar school. So, if you ever have a 9-year-old son who says he is in love, don’t laugh at him. It can happen.”

After the Roykos divorced a second and final time, their exact home addresses are up for grabs. Per biographies, Royko bounced between high schools and homes, skipping school so much he wound up at the Montefiore daytime reform school until he was old enough to legally drop out at 16. He would eventually get a high school diploma from the downtown Central YMCA.

“That was Royko’s kind of school—you could smoke in the halls, and one of the guys…had been a tailgunner during World War II,” writes biographer Doug Moe.

We know from Royko himself that his mother later opened a small cleaning and tailoring shop on California, living in an apartment behind. Per Ciccone’s bio, the shop was at California and Armitage—which is near Milwaukee.

Doug Moe writes that Helen Royko opened her own tavern where Royko helped out—the Hawaiian Paradise, on Ashland.

Sure enough, there was such a tavern at 845 N. Ashland, just north of Chicago Avenue, per the all-seeing phonebook. The building has since been demolished and replaced.

Probably Helen started the bar first and shifted to cleaning and tailoring, the business she worked at for years until her death from cancer in 1959. Royko wrote a poignant column about Helen and her shop in 1964, barely a year after beginning his column and five years after she passed away.

He must have been thinking about how proud his mom would have been to see her son go so far in his newspaper career.

“There used to be a lady who ran a dry cleaning and tailoring store on California Av.,” Royko started the column. “In a good year, she’d make $2,000 after paying her rent.”

“The store hours were 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. but that didn’t mean anything. If somebody needed their clothes at 8 o’clock on a Saturday night, they just rapped on the door and she opened the place….Her tailoring work was expert. Besides mending rips and cigaret burns, she’d make a communion dress or a graduation suit.

“At times the shabby store was so crowded it appeared prosperous. The old ladies and old men in the neighborhood found it a nice place to sit and talk.

“The lady provided chairs for them, coffee, and, if somebody would walk down the block to buy a quart of beer, she’d provide the glasses….

“When the children asked why the heck she didn’t sell the place for the little it was worth and come live with one of them, her lips would tighten….If one of them retorted that it was a rather small business and not worth all the work, she would answer that it had put food in their mouths, shelter over their heads and clothes on their backs, hadn’t it?”

Sometimes at night the lady stopped in a tavern a few doors down where everybody knew each other. “She didn’t know it, but for the price of a highball the lady got what some people spend thousands of dollars for at private country clubs.”

“She kept her store open long after she found that she had cancer—long after it became painful,” Royko wrote toward the end of the column.

A new, big, efficient modern cleaning store replaced the little one.

“But if she hadn’t died, they would’ve opened up and driven her out because they are efficient, modern and cheaper,” Royko finished. “Their business is cleaning clothes—not gossiping and letting characters sit around drinking coffee and beer. She got away in time.”

The full, heartbreaking column appears in Royko’s first collection, “Up Against It,” under the title “But Not Forgotten.”

Mike’s dad opened another bar, which Royko biographies call “the Cullerton Inn” on the Southwest side. There were several bars using the “Cullerton” moniker back then, all clustered in the general area of Pilsen and today’s UIC campus. Narrow it down to candidates using “Inn” in the name, and we can choose either the Cullerton Inn at 2001 S. Racine, since demolished for a townhouse, or the Cullerton Inn Tavern at 2632 W. Cullerton.

Royko spent enough time at his dad’s bar to fill future columns with memories like “giving monthly cash-stuffed envelopes to police bagmen for assorted favors such as overlooking a 14-year-old bartender.”

Mike volunteered for the Air Force during the Korean War and trained as a radio technician. Though Royko wasn’t a combat soldier, according to Doug Moe’s “The World of Mike Royko,” “The truth is Royko was often in harm’s way in Korea.” One of his roommates, Don Karaiskos, told Doug Moe that Mike talked little about his Korean experiences.

Moe quotes Karaiskos: “He never talked about the war in philosophical terms. But he was a forward air controller….It was a rather hazardous thing. They would go out in front in a jeep and call in on the radio strikes from the air.”

Mike was in Korea for only about six months due to the signing of the Korean Armistice. He married his childhood sweetheart, Carol Duckman, after the Air Force transferred him back to the U.S. in 1954. They would raise their two young sons while living on the third floor of Carol’s family’s home at the time, a rambling ancient Victorian in Jefferson Park at 5408 N. Central, near Milwaukee. The house was replaced in the early ‘70s by this two-flat.

In 1969, Mike and Carol bought their own home at 6657 N. Sioux Avenue in Edgebrook. Here, Royko fit his adult self-description as Bungalow Man…

…but to reach Milwaukee Ave., Mike would have had to stagger west across what is now Metra’s Northwestern railroad tracks, through the Sidney Yates Flatwoods, across the North Branch of the Chicago River, and finally through the Caldwell Woods.

Or vise versa, if staggering home to Sioux from Milwaukee Ave.

Mike would live in the Sioux Avenue house with Carol and their two sons, David and Robbie, until two years after Carol’s death in 1979.

“She was the glue,” David Royko told me. “Right after my mother died, Aunt Eleanor and Uncle Eddie—Eleanor was one of Dad’s older sisters—moved into the house. In fact, she and Eddie sold the house where they lived to move in and take care of the house, take care of our lives, fill in for Mom.

“They stayed the whole two years before we moved [to Lake Shore Drive], and they really were incredibly important to us. It’s more in hindsight that I can really appreciate how important it was. Because at the time I was a 20-year-old meathead. But Eleanor and Eddie came in and took over….Dad is the one who needed it. He was an absolute wreck.”

What do these homes all have in common? They’re all working class or unpretentious middle class homes, where you can easily picture Mike Royko, reading the paper…

…or goofing around on Christmas with his sister.

And as a former street kid who set pins at the Congress Bowling Alley on Milwaukee, shot dice in the alley with local winos and dropped out of reform school, Royko always looked askance at the places and ways of the wealthy.

Enter High-Rise Man.

READ THE REST!

Part Two: The Birth of High-Rise Man

Mike discovers a new species of privileged Chicagoans. Columns ensue, including two all-time Royko classics.

Part Three: Mike and Walter and Insults, Oh My!

Mike’s High-Rise Man column on November 5, 1981 slams headlong into his lengthy feud with top Chicago TV news anchor and commentator Walter Jacobson. Here’s an initial look at Walter—and Mike and Walter—so the November 5 column will make some sort of sense to you.

Part Four: November 5, 1981

Mike’s November 5, 1981 column appears to be a very hot take on the independent lakefront liberals of the 43rd Ward, especially Ald. Marty Oberman and his constituent Walter Jacobson. But it’s really about Richard M. Daley’s successful 1980 campaign to move up from state senator to Cook County State’s Attorney. We’ll give you a backgrounder on the politics and examine the sizzling November 5 column. Careful not to burn your fingers.

Part Five: The House on Sioux Leads to Lake Shore Drive

Mike and his first wife Carol moved their young family into a darling house in Edgebrook in 1969. That house encapsulates why Mike would always identify with poor and working class Chicagoans, and scoff at wealthy lakefront residents as “High-Rise Man.” Mike’s departure from Sioux Avenue shows us what always made him tick—and finally drove him to a big condo on Lake Shore Drive.

Part Six: Walter Strikes Back

Walter Jacobson struck back soon after Mike’s November 5, 1981 column, instigating a monumental front-page Royko High-Rise Man column on November 22 that doubles as a 1980s Chicago time capsule—and essentially ended the High-Rise Man concept. Here, we prepare for that moment of truth by examining how the paths of Mike and Walter crossed and re-crossed through the middle decades of the 20th century—and then observe their biggest collision.

Part Seven: The Last High-Rise Man [Coming]

Because there’s so much fascinating material to cover in Part Six leading up to Mike’s November 22, 1981 column answering Walter Jacobson, that 1980s time capsule of a column gets its own post here.

High-Rise Man Addendum: Bill Granger Weighs In [Coming]

A few months after Mike and Walter’s dust-up, Tribune columnist Bill Granger revisited the issue in his own indelible way. To Granger, the question is: Does your past world disappear? You know what Faulkner would say. Granger covers this age-old debate from a Chicago perspective.

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, plus the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. Sometimes you can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many iconic columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there’s riveting work covered here you will never read elsewhere.

If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career which includes a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

Brings back so many memories. Mike never became High Rise Man. He moved to an old apartment building where he could afford to live and had a good view. High Rise Man (and Woman) live in all glass and steel towers downtown, exemplified by Lake Point Tower and all its uninspiring offspring. I gave insufficient credit to old Mayor Daley back then. What we would give for the city's stability and prosperity of his reign.

3300 West Schubert