Mike Royko 50+/- Years Ago Today: Walter Strikes Back

The Life and Death of High-Rise Man, Part Six

To access all site contents, click HERE.

The Life and Death of High-Rise Man:

Part Six - Walter Strikes Back

This is the penultimate installment of “The Life and Death of High-Rise Man,” a series on Mike Royko’s High-Rise Man columns mocking wealthy lakefront Chicagoans, and the life that led him to write those columns. Not counting the coming addendum. Here, we examine how the paths of Mike Royko and Walter Jacobson crossed and re-crossed through the middle decades of the 20th century before their biggest collision in 1981. After Mike attacks Walter in his November 5, 1981 High-Rise Man column, Walter strikes back in a dramatic act of televised revenge—which will ultimately spell the demise of High-Rise Man.

To skip the series recap below, scroll down to the larger version of this graphic.

Part One: The Ascent of Royko traces Mike’s hardscrabble early life through the homes he lived in—and the life, in those homes, that led Royko to mock wealthy lakefront Chicagoans in 15 columns spanning almost 20 years. Mike called this new species of well-to-do Chicagoans “High-Rise Man.” Then, in 1981, he surprised everyone by moving to 3300 N. Lake Shore Drive.

Part Two: The Birth of High-Rise Man covers Mike’s first High-Rise Man columns, taking time to savor two of the most essential.

Part Three: Mike and Walter and Insults, Oh My! Mike’s High-Rise Man column on November 5, 1981 slams headlong into his lengthy feud with top Chicago TV news anchor and commentator Walter Jacobson. Here’s an initial look at Walter—and Mike and Walter—so the November 5 column will make some sort of sense to you.

Part Four: November 5, 1981 Mike’s November 5, 1981 column appears to be a very hot take on the independent lakefront liberals of the 43rd Ward, especially Ald. Marty Oberman and his constituent Walter Jacobson. But it’s really about Richard M. Daley’s successful 1980 campaign to move up from state senator to Cook County State’s Attorney. We’ll give you a backgrounder on the politics and examine the sizzling November 5 column. Careful not to burn your fingers.

Part Five: The House on Sioux Leads to Lake Shore Drive Mike and his first wife Carol moved their young family into a darling house in Edgebrook in 1969. That house illustrates why Mike would always identify with poor and working class Chicagoans, and scoff at wealthy lakefront residents as “High-Rise Man.” Mike’s departure from Sioux Avenue shows us what always made him tick—and finally drove him to a big condo on Lake Shore Drive.

Part Six: Walter Strikes Back [YOU ARE HERE] Walter Jacobson struck back soon after Mike’s November 5, 1981 column, instigating a monumental front-page Royko High-Rise Man column on November 22 that doubles as a 1980s Chicago time capsule—and essentially ended the High-Rise Man concept. Here, we prepare for that moment of truth by examining how the paths of Mike and Walter crossed and re-crossed through the middle decades of the 20th century—then observe their biggest collision.

Part Seven: The Last High-Rise Man [NEXT] Mike’s November 22, 1981 answer to Walter’s revenge, with the contents of its 1980s time capsule, gets its own post.

High-Rise Man Addendum: Bill Granger Weighs In [LAST] A few months after Mike and Walter’s dust-up, Tribune columnist Bill Granger revisited the issue in his own indelible way. To Granger, the question is: Does your past world disappear? You know what Faulkner said. Granger covers this age-old debate from a Chicago perspective.

Walter Strikes Back

It’s November 1981. Mike Royko is about to write his last real “High-Rise Man” piece, his oeuvre jeering wealthy lakefront Chicagoans who use words like “oeuvre,” after using the concept in 15 columns spanning almost 20 years.

And it’s all because of Walter Jacobson.

Mike’s High-Rise Man column output was dwarfed (no word play intended) by his volume of work insulting Walter Jacobson. But on November 5, 1981, Mike’s column combined High-Rise Man with Walter insults. Walter wasn’t the actual column topic, but Walter was himself a High-Rise Man, living on Lake Shore Drive in the Gold Coast.

It reminds me of the old Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup commercials where somebody holding chocolate bumps into somebody else holding some peanut butter, resulting in the happy combination of chocolate and peanut butter.

Except Mike’s November 5, 1981 column was more like two people running into each other holding live hand grenades.

And fittingly, those Reese’s ads were in their heyday in 1981, as you can see below on YouTube.

Walter soon struck back in a televised act of revenge, causing Mike to write an epic but essentially final High-Rise Man column on November 22, 1981. Why? Walter had learned, from an anonymous source, that Royko himself had become a High-Rise Man too—after moving to 3300 N. Lake Shore Drive.

Today we’ll finish analyzing the events leading up to the death of High-Rise Man, saving Mike’s November 22 High-Rise Man column for a final installment. It deserves its own post, since it’s a veritable time 1980s Chicago time capsule.

I’ll go out on a limb and assume everyone here is familiar with Mike Royko. What about Walter Jacobson?

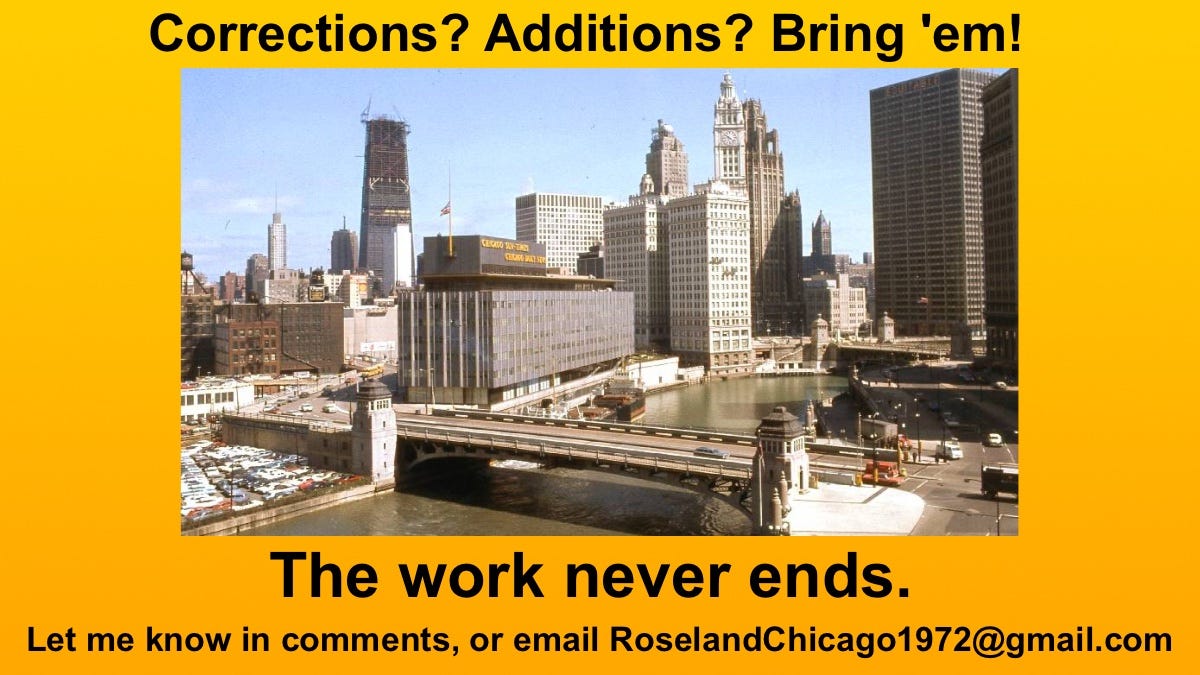

Younger Readers will be less familiar with Walter, but I suspect even many Gen X and Baby Boomer readers won’t fully appreciate the size of Walter’s footprint in Chicago history. My parents were Channel 2 news watchers—they thought they were above Channel 7’s “Happy Talk”—so I grew up on Walter, yet I was surprised myself.

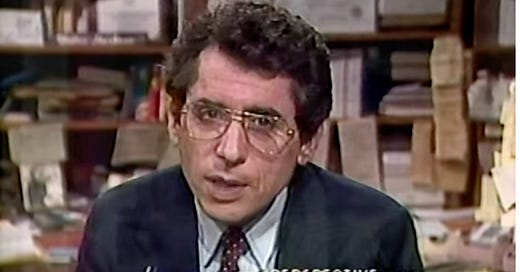

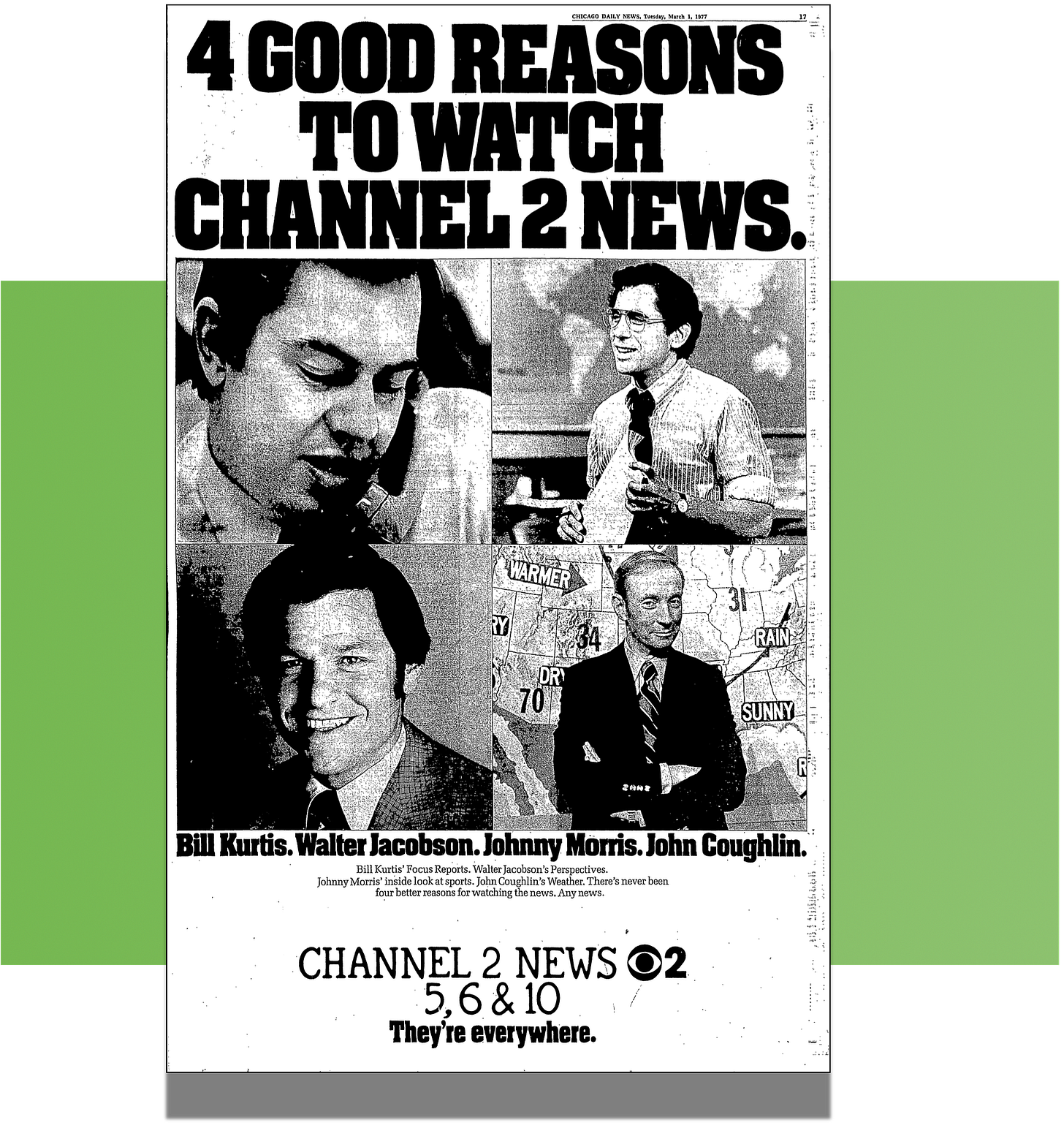

Walter Jacobson is one of the most successful Chicago television journalists of the latter half of the 20th century and the early 21st century. He became the top co-anchor at Channel 2 with Bill Kurtis in 1973, and worked here nearly nonstop until finishing a second Channel 2 stint with Kurtis in 2013.

For forty years, then, Chicago tuned to Channel 2 (or Channel 32) to see Walter, and hear his Perspective. Walter Jacobson was the only anchor who also delivered a political commentary, with original reporting, often breaking stories.

Just as Mike wrote a column every weekday, Walter gave his Perspective every weeknight. For both men, you didn’t have to stop and think about what day it was to figure out whether you’d get a dose of their opinion. You opened the paper, and there was Mike Royko’s column. You turned on the Channel 2 news, and there was Walter’s Perspective. The sheer regularity added to both men’s impact, as normal and expected a part of the Chicago weekday as hearing that it would be cooler by the lake.

Here’s a classic Walter’s Perspective, on gun control, from December 8, 1980—the day John Lennon was assassinated. Go to 6:60 for Bill Kurtis’s intro, then sit back and enjoy Walter’s outrage over the NRA’s control of Congressional votes. Watching Walter was always so cathartic. Walter’s opener: “Chances are that John Lennon would be alive tonight if he had stayed in his home in England instead of moving to the United States, which is the gun capital of the world. In England, they don’t allow guns.”

Obvious? Sure. But you like to hear somebody say it anyway, and sound as exasperated as you feel.

Walter Jacobson was both one of the most celebrated stars of Chicago TV news, racking up awards and honors, and also the most ribbed—sometimes for the very qualities that won him plaudits. Walter was combative, mercurial, excitable. He knew what interested viewers, for better or sometimes worse. As noted in Part 3, Walter’s career pièce de résistance, for fans and critics alike, remains his 1991 “Mean Streets” series. Channel 2 make-up artists transformed Walter into a homeless person for 48 hours spent outside during a frigid Chicago winter. Walter wandered the Loop and, of course, Lower Wacker Drive.

A publicity stunt? Yep. What’s your point. “Mean Streets” was a sweeps month series. And I assure you, everybody watched it.

At 87 in 2024, Walter Jacobson still provides a weekly commentary for WGN radio which airs during Bob Sirott’s morning show, Thursdays at 9:25 AM. It’s also collected and available on the station’s website, or as a podcast.

As we’ll see, Walter Jacobson is the Chicago Icarus who flew closest to the searing hot sun of Mike Royko’s Chicago journalism celebrity. To Royko fans, that sounds exactly like the hubris the Greek myth is meant to warn us against. But unlike Icarus, Walter’s wings didn’t melt. When Walter soared into Mike in November 1981, they both got singed.

High-Rise Man Reprise

This series started by using Mike Royko’s early homes to consider the hardscrabble life that led him to routinely mock upscale residents in the new high-rises that multiplied in post World War II Chicago, especially along the North Side lakefront. As mentioned above, Mike wrote 15 columns using the High-Rise Man concept, spanning almost 20 years

In Part Two, we blitzed through the most prominent High-Rise Man columns. My favorite clip has to be Mike’s reworking of Carl Sandburg’s pièce de résistance, in a 1968 column lamenting the bourgeois tastes just starting to become common in Chicago:

“It is not a paint-flecked pants town any more,” wrote Mike as a preface. “The city of the three-flat with flowered wallpaper and linoleum in the parlor, the lunch pail, the shot-and-beer and count-your-change, has become something else: San-Fran-York on the Lake.”

When I wrote that post, this is how I considered Mike’s Chicago:

Mike wraps this column with one of his masterpieces…which I for one would put up against that Picasso any day of the week. Me, I’d say this reworking of Carl Sandburg’s pièce de résistance reflects Mike looking sideways at an emerging and future affluent city where, he feared, too many people would know a sterile high-rise development better than their own heroic hometown poets.

Now another facet occurs to me. Yes, Mike is mourning the passing of a more industrial, factory-employed, working-class Chicago as the more middle-class and affluent post-World War II Chicago emerges. But perhaps he is also unconsciously mourning the fact that he is part of that Chicago population leaving their humble beginnings behind—even in 1968, long before he would ever have imagined himself moving to Lake Shore Drive. It reminds me of the elves leaving Middle-Earth in Lord of the Rings.

Mike Royko was part of the paint-flecked pants town he saw receding into the past. He started mocking the burgeoning wealthy lakefront High-Rise Man Chicagoans in 1967, the same year he began laying into Walter Jacobson in a whole separate branch of columns.

Royko’s cracks against Walter would spread across at least 17 columns in the Daily News; 29 columns during his Sun-Times years; and 16 columns at the Tribune. That’s 62 columns, minimum. I probably missed one or two when Mike used a fleeting nickname I failed to search for. Royko’s last Walter snipe appeared in 1995, two years before Mike’s untimely death at age 64.

Sixty-two column references. These days we’d say Walter Jacobson was living rent-free in Mike Royko’s head. Even Walter was shocked at the sheer volume when I told him.

“Really,” he marveled.

Small, or small-minded?

Here we must acknowledge that while some of Mike’s jibes at Walter are merely light-hearted fun, as a whole they’re not among Mike’s finest moments. Most are not memorable. They’re just quick one-offs. Some aren’t even funny. A few come off as just plain mean-spirited. This becomes clear when you collect and read them together, as I have.

Mike’s focus on Walter’s short stature, in particular, would be puzzling and probably horrifying to Younger Readers. Perhaps the least offensive joke in this group would be from Mike’s terrific July 7, 1989 column on the closing of the Midget’s Club, a Southwest Side tavern run by a married midget couple for over 35 years. Pernell and Ethel St. Aubin ran the Midget Club, catering to other small people with a special bar only 32 inches high. This was a real thing, and real people. Mike didn’t make it up.

Pernell St. Aubin told Mike that he used to field calls from TV and movie bookers.

“I still do some of that, but there isn’t as much demand for small people as there used to be,” he said. “Today, most of the small people go to college and have a better chance at other things.”

Mike’s aside: “I don’t know if he was referring to the college-trained Walter Jacobson, but if so, I’m pleased for Walter.”

To Chicagoans in the the latter half of the 20th century, this was a fun little celebrity spat. Yes, it was fun to hear that Mike had insulted Walter, and vice versa! They were like members of an extended Chicago family—and don’t pretend it isn’t hilarious to hear your relatives talk behind each other’s backs. Or yell right in each other’s faces.

Walter and Mike were both well aware of that themselves, as are all celebrities who engage in public feuds. Remember, for better or worse, Walter knew what attracted an audience. “Of course, our war of words is good for both of us,” Walter wrote in his memoir, “luring his readers to me and my viewers to him”.

However, some people (besides Walter) were offended even at the time—as we can see from Mike’s own letters columns.

On March 9, 1982, Mike printed a letter from Lynda Davis cautioning him to be careful when joking about Walter’s height, because some gullible people would believe that Walter Jacobson was only three feet tall.

Mike responded with a fabricated picture of Mayor Jane Byrne towering over a pint-sized Walter. Mike’s comment claimed that Walter was “obsessed” with potholes, because he “fears that he will tumble into a pothole someday, won’t be able to climb out, and a city crew will come along and bury him under a pound of asphalt.”

FWIW, Younger Readers should know that Photoshop didn’t exist back then. Picture manipulation, then, was a rare feat accomplished only by professionals. Knowing that actual professionals had taken the time to create a picture of Mayor Byrne towering over Walter Jacobson made the picture above funnier than it probably seems now.

In Mike’s next letters column, reader Elizabeth Van Der Molen scolded Mike and said he owed Walter an apology. Mike insisted Walter had “contracted a rare ailment called teenyitis, which causes a person to become teenier and teenier….Unless a cure is found soon, some alderman is going to just slip him into his pocket, and that will be the end of little Walter.”

The thing is, of course, why was Mike picking on Walter’s height to begin with?

Younger Readers, I can only share with you yet again a truth I hold to be self-evident: The past is not a safe space. Mike Royko, while living in his present, lived in your past. In that strange but sometimes wonderful time, the number one television show in America starred a foul-mouthed bigot who was absolutely hysterical. Personally, as a child, I found it normal that the entire world told jokes about how stupid I and my relatives were, being Polish Americans—or “Polacks” as we were known. Today, autocorrect doesn’t even want to let me type that word. The past isn’t something to approve or disapprove. It’s just what happened.

To close this section, I’m reminded of former Tribune editor Richard Ciccone’s introduction to his Royko biography, A Life in Print. After covering President Jimmy Carter’s 1977 inauguration, Ciccone was sitting in a D.C. bar at a table of reporters from papers like the LA Times and the Boston Globe. Elitist types. We’re meant to figure they’re a bunch of WASPy Harvard grads. Somebody saw Royko sitting at the bar, invited him over, and introduced everybody, ending with, “And of course you know Dick Ciccone.”

Ciccone knew Royko hated the Tribune and anybody who worked there. He wasn’t surprised when Royko answered, “He’s a greaseball from the Tribune. Probably connected to the mob.”

Ciccone didn’t care. He hailed from a small Pennsylvania steel-mill town where the ethnic crowd was a mirror image of Royko’s childhood Chicago.

“Yeah, I know him,” Royko added. “He’s a phony wop. I may not stay at this table. I don’t like to drink with wops.”

“No one laughed,” Ciccone recounts. “David Nyhan of the Boston Globe, who towered over Royko, interjected, ‘Hey, Ciccone’s my friend and if you don’t want to sit here, fine, leave.’

“Royko took a sip and grinned. ‘Dick knows I was just kidding. In Chicago we all talk that way to each other.’”

Ciccone was proud to have Mike Royko call him a wop. He probably told that anecdote to everybody he knew before using it in his book’s introduction.

Two crucial years for Mike and Walter: 1967 and 1981

When Mike Royko started in on Walter in 1967, Jacobson was just a TV reporter for Channel 2 news. See Part Three for a more complete look at Royko’s early attacks. Here we’ll just repeat Walter Jacobson’s first appearance in Mike Royko’s column, which was also, fittingly, Mike’s first annual Cubs quiz.

Mike claimed that Cubs players threw their underwear at Walter while he was a bat boy. This Cubs quiz is the first public manifestation of the nascent feud. We’ll look at the feud’s origin story under the Walter’s Path section farther on.

Was it all just in fun? Mike’s 1967 Cubs quiz is certainly a mild first jab. But no.

“They were not on friendly terms, it was a real thing,” says Judy Royko, Mike’s second wife. “Mike was not putting that on.”

“It was a cruel relationship or lack thereof,” says legendary Chicago reporter and anchor Carol Marin. “Royko had given Walter plenty of ammunition too so they sort of deserved each other at the end.”

“I think it was personal with Royko, but I don’t know,” shrugs University of Illinois at Chicago political science professor emeritus (and former alderman) Dick Simpson.

What does Walter think? In his memoir, Walter takes it for granted that Mike’s “loathing” was real. The only question, to Walter, is why.

Walter comes up with two specific reasons which we’ll explore—their initial competition working on opposing newspapers, and once Walter moved on to TV, the larger 20th century existential struggle between newspapers and television. More bluntly, Walter figures Mike was jealous of his gigantic paycheck.

But we can only speculate, because Royko never told anybody. And Walter never talked to him about it.

“No bellying up to a bar for me with Mike Royko,” Walter writes in his memoir. “He wouldn’t hear of it, and I’d be uneasy. He’s a grouchy guy. After a slurp too many, he turns treacherous, egging for a fight, too tough for me.”

Once Mike focused on Walter as a target, his shots kept coming—though he had to keep aiming higher all the time. Walter rose from on-air reporter to star anchor after he teamed up with Bill Kurtis on Channel 2 in 1973, simultaneously delivering his Perspective on weeknights. By the end of the decade, Bill and Walter had taken Channel 2 news from last to Number One.

As mentioned earlier, Mike’s High-Rise Man columns collided with his Walter insults in Mike’s epic November 5, 1981 column excoriating 43rd Ward lakefront liberals, especially Ald. Marty Oberman….

—and Walter. (The 11/5/1981 column is really about Richard M. Daley’s successful 1980 campaign to move up from state senator to Cook County State’s Attorney. See Part Four to fully deconstruct the byzantine politics there.)

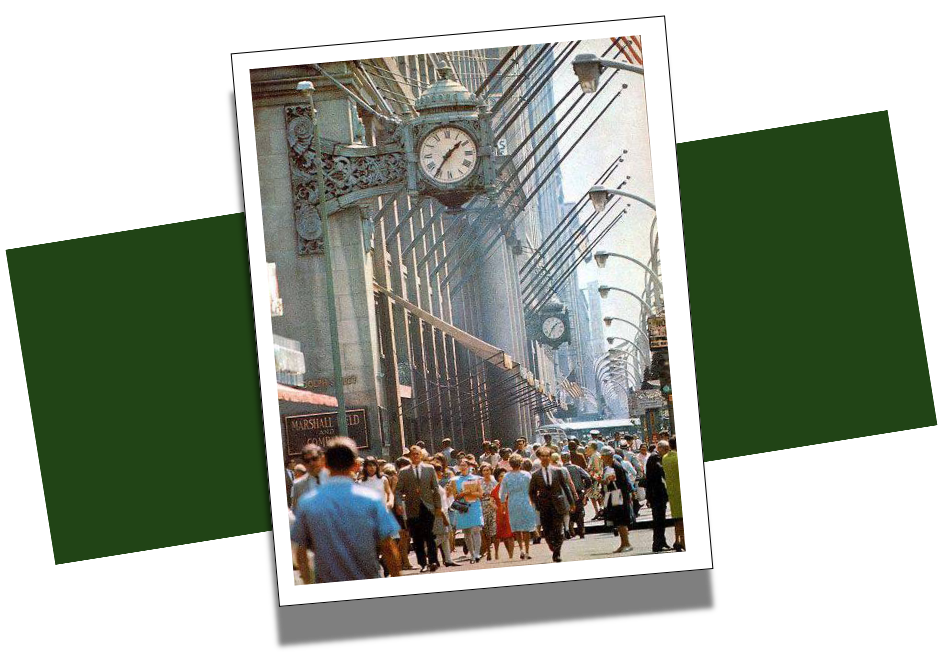

We can easily pinpoint Walter’s high-rise condo in Marty Oberman’s ward because it happened to be right next door to the diplomatic mission of the Polish government, which was at that time a brutal Communist dictatorship cracking down on its populace with martial law after Solidarity union activists organized strikes, walkouts and factory sabotage to fight the Soviet puppet regime.

According to a December 30, 1981 Sun-Times article, the Polish government “was preparing to draft all unemployed workers for conscript labor teams.” In Chicago, this led to raucous protests at the Polish diplomatic mission. Neighbors, including Walter, grew weary of the uproar.

“Vandalism of the diplomatic mission at 1530 N. Lake Shore Dr., especially by the throng that shattered windows and pelted the building with burning flares, raw eggs and jars of red paint on Sunday, has distressed several residents of the building next door at 1540 N. Lake Shore,” read a related Sun-Times article by Barbara Shulgasser and David S. Robinson:

“I think it’s becoming a joke,” said Walter Jacobson. “These people have already accomplished their purpose. They’ve already demonstrated what people should see. From now on I just hate their guts….They have made their point, but why go from here on?”

You have to love Walter’s raw honesty: “From now on I just hate their guts.”

Like Mike, that’s one of the main things people loved about Walter’s work—a strong, direct opinion. No mealy-mouthed in-betweens. Mike once said when he started the column, that was one of his rules—to always come down on one side of the issue or the other. It’s harder than it sounds, and Walter followed that rule too.

Anyway, Walter’s lakefront address in Ald. Marty Oberman’s ward meant he fit right into Mike’s November 5, 1981 High-Rise Man column roasting Oberman. So in the process, Mike also skewered Walter.

As far as I can see, Marty Oberman didn’t deserve Mike Royko’s derision, a topic covered in Part Four. Mike first turned on Oberman in his September 26, 1980 column, where he wrote that he used to like Oberman, adding:

In the sizzling November 5, 1981 column that soon drove Walter to the act of revenge that would end High-Rise Man, Mike burned Walter three times.

Here, in a portion mentioning Oberman’s habit of riding his bike to work…

…here, alluding to the fact that Oberman was running for Illinois attorney general…

…and here, where Mike repeats a common critique of Walter for “bouncing” while delivering his commentaries on Ch. 2 news, meaning he would lean forward excitedly sometimes as he talked.

For that November 5, 1981 column alone, not to mention the 14 years of Royko insults preceding it, you see why Walter soon struck back.

But to fully appreciate how Mike Royko and Walter Jacobson got to November 1981 in the first place, we must trace their continually crossing paths over the middle decades of the 20th century. We’ll see how their orbits crossed several times before their first head-on collision in 1963.

Then we’ll get back to 1981—with a vengeance.

Note to readers of this series: I’ll quickly recap some previous biographical information here, but with much new material relevant to the Mike-Walter dynamic, including an overview of Mike’s early days at the Daily News you won’t want to miss.

Mike’s Path

Born in 1932, Mike Royko grew up in a struggling Polish-Ukranian immigrant family that split up after his philandering, hard-drinking dad kicked his mom hard enough to break her ribs. The family, together and apart, lived in a succession of flats always “within staggering distance of Milwaukee Avenue” as Mike recalled—basement flats; flats above the tavern run by the family; and a flat in back of the little cleaning and tailor shop his mom ran for many years until her death. (In mid-20th century Chicago, apartments were “flats” and bars were “taverns.”)

Married or divorced, the Roykos never had enough money for their own telephone.

Six-year-old Mickey Royko became a Cub fan for life after Mike Sr. took him to Opening Day in 1939. “By the summers of World War II, Mickey and (little brother) Bob would go to games on their own,” writes Ciccone in A Life in Print. “They walked the five miles from Milwaukee and Armitage to save streetcar money for a Coke. They carried fried egg sandwiches in wax paper and waited outside the left field gate until they were allowed in free in exchange for setting up the folding chairs that were used in the box seats.”

Young Mike soon found many jobs around the neighborhood, like setting pins at the Congress Bowling Alley.

But that incorrigible Royko kid still ended up in reform school. He dropped out at 16 and worked menial jobs before getting his diploma at the downtown Central YMCA. Next, Mike enlisted in the Air Force during the Korean War, spending a year deployed to combat zones as a radio operator. Though he wasn’t a combat soldier, biographer Doug Moe notes in The World of Mike Royko that “Royko was often in harm’s way in Korea.” Mike’s Washington base roommate pointed out that radio operators like Mike worked ahead of others— “It was a rather hazardous thing. They would go out in front in a jeep and call in on the radio strikes from the air.”

While finishing his service stationed in Washington State, Mike married his secret childhood crush, Carol Duckman. They honeymooned for a weekend at a little hotel near the base. Back in Chicago, the young couple lived in a basement flat before moving in with Carol’s folks.

Royko left the Air Force in March 1956 and went straight to work for the Lincoln-Belmont Booster, a Lerner neighborhood paper. Within six months, he’d jumped to the legendary City News Bureau, a kind of local AP for Chicago media that constituted a grueling reporter boot camp. He soon tried the four major dailies, hoping to move into the big-time. But Royko got turned down everywhere, as biographer Moe recounts.

In Mike’s words: “First thing everybody said was, ‘Why didn’t you finish college?’ That wasn’t easy. It stays with you.”

In fact, Mike did not attend college at all according to son David Royko. At most—and even this is sketchy—he may have taken a couple of night classes at Northwestern during his first year out of the Air Force. That lack of a diploma and concomitant social standing stuck with Royko, perhaps especially because he was a voracious self-educated reader who had sprinkled his letters to Carol during his Air Force service with quotes and references from Rouchefoucauld, Emerson, and Keats.

A huge folk, blues and jazz fan, Royko also dove deep into classical and opera. He wrote music reviews for the Daily News’ Panorama section as a young reporter. Here’s Royko in a nutshell: “He took a great deal of pride in being able to differentiate performances of Beethoven symphonies or whatever,” David Royko told Ciccone for A Life in Print. Mike loved attending the Chicago Symphony after Sir Georg Solti took over, said David, but didn’t go often:

“The music was his scene, but the scene itself wasn’t his scene.”

David has his dad’s knack for turning a pithy and deeply true phrase.

Royko’s lack of that societal stamp of intellectual recognition must have re-enforced his dislike for the conservative Tribune, and definitely affected relationships with some people from more elite backgrounds. Take James Hoge, Mike’s editor after the Daily News folded in 1978 and he moved to the Sun-Times.

Hoge was a tall blond handsome Yale grad, named Sun-Times editor in 1968 at the tender age of 33—basically a newspaper version of Robert Redford from The Way We Were.

“Hoge and I have never been friends, let’s say,” Ciccone’s bio quotes Royko from a More Magazine interview. “Part of this, I think, is because we come from different social backgrounds. Hoge’s had all the breaks. Good looks, rich parents; he came to the Sun-Times right out of Yale. Me, I put in time at the City News Bureau first, then had to bust my ass to get my job. But I’m very impressed with Hoge….I don’t think I could ever picture myself going on a canoe trip with the guy or anything, but that’s irrelevant.”

Shut out of the major dailies, young Mike Royko, in his own words, busted his ass at City News for nearly four years before finally landing an entry level job at the Daily News in 1959. He started out as a night rewrite man, went on to police reporting with the byline “Michael Royko,” and in February 1962 got dispatched to cover the Cook County government beat. In July 1962, Royko added a weekend “County Beat” column in the op-ed section.

“County Beat” reads as if Royko jumped fully formed from the forehead of the Newspaper Columnist God. Here’s his first column and column likeness, a line drawing:

And yes, we’ll do a post on the County Beat phase of Royko’s career. It will be well worth subscribing FREE right now to make sure you don’t miss it.

It was during this time that Michael Royko became Mike Royko.

As Royko started his weekly County Beat column in 1962, the Daily News’ star columnist Jack Mabley had recently jumped to the rival Chicago’s American—a year earlier, in 1961. Mabley’s column had run in the Daily News on page 3. But a few weeks before Mabley suddenly quit, the paper created “a columnist’s page” much farther back in the paper to put all the day’s columns. So the columnists got shoved back and crowded together on page 14, sometimes even page 20.

Maybe that’s the real reason Mabley left, though the rumor was that he resigned because they redecorated the Daily News offices and told him he had to give up his old wood chair.

Hmmm. Moving the star columnist from Page 3 to Page 20…or the old green chair. You be the judge.

Here’s the Daily News pumping up their lead columnist Jack Mabley in a full page promo on January 1, 1961, about six weeks before he quit. It sounds like the ones they’d start running for Mike Royko in a scant few years.

If the Daily News liked Jack Mabley so much, they probably should have kept him on Page 3. And given him a better logo than this, without even a drawing or photo:

When Mabley exited in 1961, the Daily News immediately gave his spot on “the columnist’s page”—way back on page 14 or 20—to John Justin Smith. But that’s not the same thing as page 3, is it. Smith was a 24-year veteran of the paper and the nephew of famous former Daily News managing editor Henry Justin Smith.

Royko, meanwhile, parlayed his County Beat column in the op-ed section into a general interest column by September 4, 1963, running Tuesdays and Fridays on the new columnist’s page alongside John Justin Smith. Here’s the top of Mike’s very first general interest column:

And then, less than three years later, the paper promoted Royko to Mabley’s old spot on Page 3. Note that the Daily News treated Page 3 as an inner front page, a front page for local news. Page 3 was the real prestige spot.

They even ran this promo for Mike’s arrival on Page 3—which, if I were Jack Mabley, I would have found profoundly annoying:

Mike Royko quickly exploded as the city’s supernova columnist, his light blotting out all the smaller stars in the Chicago newspaper galaxy…even, quite soon, Jack Mabley.

Mabley remained prominent until his retirement in 1982, but he didn’t set the conversation anymore. His column moved to Chicago Today when Chicago’s American got reworked into a tabloid by its owner, the Trib, and then to the Tribune itself after Chicago Today shut down. In 1988, Mabley came out of retirement to write for the suburban Daily Herald, continuing there for another 16 years.

So the man had staying power and a loyal audience. I’ve read a lot of interesting Mabley work by now and plan to do a post on him. But like everybody else, Mabley’s work was and is overshadowed by Mike Royko.

I truly appreciated the nature of Mike Royko’s gigantic shadow when I started researching this site’s chapter on Chicago newspapers. I wasn’t as familiar yet with Chicago Today or its predecessor, Chicago’s American. For Chicago Newspapers Circa 1972, I talked to any working reporter from the time period I could get on the phone or email, asking everyone their opinion of the American and Today. [And I’m happy to update the post and talk to more Today reporters! Please contact me if you fall into this category, especially if you are Bruce Vilanch.] Quite a few people—again, people who were contemporaneously working Chicago journalists—told me that Today and the American didn’t have a star columnist.

They completely forgot about Jack Mabley. It’s not fair, but there you are.

We’ll leave Mike’s early path here in 1969, just after his first jab at Walter in print, via his 1967 Cubs quiz. After six years as the Daily News’ star columnist, Royko finally felt he could afford his own home. Mike and Carol moved their two young sons from their grandparent’s house to a darling home in Edgebrook on the Northwest Side.

Walter’s Path

Five years younger than Royko, Walter Jacobson spent his childhood until sixth grade in Rogers Park before the family moved to Glencoe. Walter’s grandparents were all Russian-Jewish immigrants, but his insurance salesman father got the Jacobsons to the North Shore. In his 2012 memoir, Walter’s Perspective, Jacobson recalls home life as “uncomfortably tense” between his parents, but there were no broken ribs like at the Royko home.

Like Royko, Walter Jacobson turned into a Cub fan at a tender age—eight years old, after listening to the Cubs lose the 1945 World Series on the radio. By ten, Walter recalls taking the L after school from Rogers Park to Wrigley Field, then “dodging the ticket-takers to get into the bleachers”.

Did Walter ever pass Mike Royko at one of those afternoon games, maybe sit near him in the bleachers? Or did they always visit Wrigley Field on different days? I like to think they bumped shoulders at least once, maybe getting a Coke.

During high school at New Trier, ambitious young Walter worked for the local Glencoe newspaper and, by writing directly to Cubs owner P.K. Wrigley, got himself hired as a Cubs batboy for the 1952 and 1953 seasons. That’s where he met Jack Mabley, then baseball writer for the Chicago Daily News.

As we know, Jack Mabley left baseball and became the Daily News’ lead columnist. Walter peppered Mabley with letters and calls every year, asking for a summer job as his assistant. Mabley took the calls, always saying no—until 1958, while Walter was still at Grinnell College. Walter was in.

That summer, Jack Mabley got an invitation from an Indiana nudist colony. He sent Walter, printing his assistant’s account verbatim the next day in his column space. As Walter’s memoir preface puts it: “I earned my first newspaper byline after visiting a nudist colony whose naked female proprietor told me that if I wanted the story, I’d have to take off my clothes.”

So: Walter Jacobson went to work in the old Daily News Building on Madison and the Chicago River one year before Mike Royko—and even got his byline in the paper first.

Walter finished college, then worked at City News Bureau for the summer of 1959—juuuust missing Royko, who’d moved on to the Daily News. In fall, Walter left for New York, earning a master’s degree in journalism at Columbia University. In 1960, after a honeymoon trip to Europe and the Middle East courtesy of his new wife’s parents, Walter and Lynn Jacobson headed home to Chicago.

Walter landed at Chicago’s UPI office. His memoir includes a hilarious story about getting fired, six months later, for independently researching a story on shoplifting at the State Street Marshall Field’s during his off hours. Without telling anybody at UPI. Walter got caught, which would have made a great anecdote for a story—but his UPI editor wasn’t amused when the store called to confirm Walter’s identity.

Note: Validating my theory that Don Rose knows everybody who lived in Chicago in the last say 100 years, he writes to say, “Also it is quite possible that the person who fired Walter from UPI was my father-in-law, Jesse Bogue, who I believe was in town as Central division news editor that year.”

Back in the job market, Walter went to Chicago’s American. The Tribune had bought the American in 1956, and would turn it into the tabloid Chicago daily Today for 1969-1974 before shutting it down. The American was the latest iteration of William Randolph Heart’s first Chicago paper, and all Hearst papers were notorious for covering scandal, blood and guts. (Younger Readers, Hearst was the prototype for Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.)

The conservative Republican Chicago Tribune tamped down the blood and guts in its new acquisition, but most of the American’s staff moved into the new offices in the Tribune Tower annex. Thus the American remained, fairly or not, the most disreputable paper in town. Assessing the new Chicago Today in 1970, the Chicago Journalism Review observed that the predecessor American had been “the cheapest whore in town, bending over backwards to titillate all comers at a nickel a throw.”

So, as Walter headed for the American in 1961, the paper had more than one foot still firmly planted in the wild Front Page days of Chicago journalism. Nobody at the American cared why the new applicant had gotten canned from his first job in just six months. Heck, that was probably a plus. The American put Walter right to work—on the county beat.

In his memoir, Walter writes that he’d already been talking to an editor at the American before he got fired by UPI. Also, 1961 is the same year his mentor, Jack Mabley, jumped from the Daily News to the American. Walter doesn’t mention that, so it’s unclear whether Mabley helped him in the door.

Either way, Mike Royko and Walter Jacobson finally ended up in the same place at the same time as adults: the Cook County Building press room.

Here is the room where Mike Royko and Walter Jacobson first met—in Walter’s words, from his memoir:

It was more than half a century old and looked, and felt, every day of it. A cement floor of some six hundred square feet was covered by a sheet of muddled linoleum peeling at the corners and cracked most everywhere else. The walls were whitewash turned dirt-gray and smudged by ink-stained fingerprints, pencil scratches, and an array of telephone numbers written in a hurry….There were four cheap wooden desks in the pressroom, one for each reporter, painted brown and separated by so little space that we covered our mouths when we talked on the telephone. A large, oblong metal table slopped with old newspapers, county directories, and the Yellow Pages sat in the center of the room underneath fluorescent light fixtures up ten or twelve feet on the ceiling, which also was covered with linoleum. Many of the bulbs were burned out, probably had been for many years.

Both our young reporters, Mike and Walter—and we cannot emphasize this too much—were trained during the rapidly waning Front Page days when reporters from other papers were truly competitors, and competitors were enemies. You didn’t tweet glowing compliments about the other paper’s reporters and their stories, as is common in 2024, and not just because there was no Twitter. Back then, you suffered your competitors to live—that was all.

The Front Page was a hysterical over-the-top play by former Chicago reporters Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, but it was based in the reality of that world. (OK, the clip below is from the rom-com film version His Girl Friday, but c’mon—this one has Cary Grant.)

In later years, Mike and Walter would both enjoy boasting about their early Front Page ways. Walter in particular was sometimes accused of continuing to use the old tricks long after they’d gone out of favor. Royko fans will recall that Mike got a shiny silver star badge at a dime store to help report the notorious 1956 murders of the Grimes sisters for City New Bureau. He used the badge to pose as a coroner’s investigator to interview the Grimes’ neighbors and others.

Walter’s berth at the American gave him a master class with one of the most legendary Front Page reporters of all time: Harry Romanoff, commonly called “Romy,” then in charge of the city desk. This is the guy who called Richard Speck’s mother during the early hours of reporting Speck’s horrendous 1966 mass murder of eight student nurses on the South Side. Romy pretended he was Speck’s attorney to get the full story of the killer’s troubled life.

Fun Fact: Romy spent a lot of time on the phone. Chicago Today reporter Mary Knoblauch, who got the chance to observe Romy in the ‘60s, told me he loved eating fried chicken. Every once in a while Romy’s phone stopped working and he summoned The Phone Company, which in those days actually owned all the phones. Crazy, right? Knowing Romy well, the phone repairmen came prepared with the correct spare parts: The receiver was always clogged with chicken grease.

Walter would use Romy’s training during his stint in the County Building pressroom, earning a paycheck and Mike Royko’s undying enmity. One more thing before that story: Remember, to Mike, Walter wasn’t just any opposing reporter in the County Building press room in those waning Front Page days. Walter was Royko’s most direct competitor, because they worked for the two evening papers in town, with similar deadlines.

The Paths Cross

One day, Walter was alone in the press room during lunch when Cook County Assessor Parky Cullerton walked in with a stack of press releases.

“Taxes goin' up. Pass these around, okay?" Parky told Walter, and left.

Walter knew a scoop when he saw it. He stuffed the press releases in his pocket and bolted back to the American’s press room to write the story, looking forward to beating Royko and the Daily News by a full news cycle.

“I know Royko would do exactly what I'm doing exactly the same way,” Walter writes in his memoir. “Nonetheless, when he finds out, he's incensed—which is not a good thing, Mike Royko being incensed. His personal edge is no less jagged than the edge of his column, and he doesn't, or maybe can't, keep it in check. He bounds up the stairs to rail on Assessor Cullerton, who is not to blame, and he sticks me into his craw, and will keep me there for twenty years, occasionally, as you'll see later, spitting me into his columns with anger or sarcasm.”

But Walter claims he didn’t care. “I had my story and was hightailing it through the Loop to my editors at the American. I wasn’t thinking about Royko, only about the deadline for our last edition, and the likelihood we’d be ahead of the Daily News by twenty-four hours.”

This was gigantic, especially for the County beat. As Walter notes, “What matters to readers is information about taxes.” And: “What matters to the newspaper is ‘Chicago’s American has learned.’” That’s because the value of a story is often not the substance, per Walter and any media observer, but the number of readers and viewers it draws, which often depends “on what a newspaper or television station has that the competition does not.”

You don’t think Royko caught hell from his own editor at the Daily News for missing that one? At least the reporters for the morning Sun-Times and Tribune had time to read that evening’s American, then spin something for their much later deadline for the morning papers the next day.

But here is where I have to confess that I wasn’t able to confirm this foundational anecdote by tracking down the big assessor’s office story broken by Walter in the American and missed by the Daily News’ Mike Royko. They could only have overlapped at the County Building from February 1962 through fall 1963. That’s when Mike started the beat (the exact day is easy to pinpoint in his clips) through when Walter left for his first stint at Channel 2. Walter knows he was at Channel 2 by the time John F. Kennedy was assassinated, putting a definitive end date on his American days.

But there were no tax increases during this time period, and not many instances where Parky Cullerton even made the papers. This was fairly easy to review in the digital archives of the Tribune, Sun-Times and Daily News. The American (and Chicago Today) aren’t digitized, so I had to go old-school and slog through microfilm, but this too is still physically possible at the library. There were a couple of assessor-related stories that I thought could perhaps qualify as a scoop for Walter, but none met the requirements of being covered by Walter in the American and not appearing simultaneously in the Daily News.

That doesn’t mean Walter’s basic scenario didn’t happen. I believe something similar happened, just not with Parky Cullerton. But I can’t read Chicago’s American every day in 1962 and 1963 to find it. Even I have my limits. As legendary Chicago media columnist Robert Feder put it when we talked about the Royko-Jacobson feud, “It’s definitely not apocryphal. We have enough versions of it, and Walter recalled it in sufficient detail that I don’t question that it happened.”

So let’s just agree that Walter scooped Mike big-time by scampering off with a sheef of press releases from one of the County officials, or something just as bad, probably getting Mike in hot water with his bosses.

What a snotty little Richie Rich whippersnapper Walter must have seemed to Mike Royko.

Plus Walter was a college boy. Richie Rich goes to college. Remember Mike’s 1982 column on the Midget Club? “Today, most of the small people go to college and have a better chance at other things,” club owner Pernell St. Aubin told Mike, who added, “I don’t know if he was referring to the college-trained Walter Jacobson, but if so, I’m pleased for Walter.”

Walter was five years younger, no military service, and from the North Shore of all places. Royko walked five miles to Wrigley Field with a fried egg sandwich in wax paper hoping to set up chairs for a free ticket; Walter took the L from Rogers Park as a kid, and later got to hang around the dugout as batboy.

In 1962, six months after graduate school at la-dee-da-da Columbia University, Walter already had the exact same job Royko labored years to land with his high school diploma from the downtown Central YMCA.

Can you imagine if Walter told any stories about his European honeymoon in the County Building press room? Or bragged about having his first Daily News byline in 1958? Royko probably wanted to slug Walter on a daily basis.

The Parky Cullerton press release—or whatever it was—became “a seminal moment,” says Robert Feder, but he points out that such relationships often evolve over time as well.

Walter worked for the opposition—Chicago’s American—and could be hated on that basis alone when the two men first met. Then, as Royko began building his reputation as a columnist, his main print rival was his Daily News predecessor, the American’s Jack Mabley, whose move from the Daily News made Royko’s column possible. As Feder points out, “you could not have known Walter Jacobson…without connecting him with Mabley.”

Walter moved on to TV news by 1964, but he’d always be the guy who used to be Jack Mabley’s legman.

And how did Mike Royko come to feel about Jack Mabley—competitive much?

How could he not? Royko was competitive with anybody who worked at another paper, but Mabley was the star columnist in town who Royko would have been dying to surpass, and then leave in the dust.

That said, there isn’t much information readily available on this topic, though I hope to find more for a future post. I could find only one place in which Royko directly mentioned Mabley, in his March 12, 1990 column. Recall that Royko left the Sun-Times in 1984 after Rupert Murdoch bought the paper, heading to the only paper left in town, the Tribune. Mabley had retired from the Tribune two years earlier, so the two columnists missed each other once again.

By 1990, Royko was firmly ensconced at the Trib, and Mabley had come out of retirement to write for the suburban Daily Herald—where he criticized Royko.

As Mike explains the situation in the 3-12-90 Trib column, he’d written an earlier piece about a survey of students and teachers, which found most of them thought the kids were only interested in a good time, perhaps endangering the future of American democracy. You know, like kids at every other point in American history!

So Mike had written a column suggesting that a draft for 18-year-olds with an alternative national service program would be good for 1990’s young people. Many teachers assigned their students to write essays on Mike’s idea, which they sent to Mike.

The students didn’t like the suggestion of taking away their youthful freedom. Mike found the student essays were awful and proved his point. In a subsequent column, he printed some excerpts from one batch, failing to note from the teacher’s cover letter that her students were special education students.

The outraged teacher wrote to Mike, but with hundreds of letters coming in every week, Mike missed it.

Well, it turns out that teacher was an old friend of Jack Mabley’s. In his Daily Herald column, Mabley wrote that Royko was guilty of “a shoddy breach of journalistic ethics.”

Mike responded on March 12, 1990. He admits in this column that he was wrong to miss the teacher’s first note, and that he would not have included the special education students letters otherwise. He’s sorry he missed her follow-up note, and thus missed the chance to apologize to her directly. But Mike points out that nobody should have been humiliated by the initial column because he didn’t identify the students’ names, teacher, school, city or state.

Nobody would have known that the students had been held up for ridicule if Jack Mabley had not publicized the whole thing.

“Mabley said that we’ve known each other for 30 years,” writes Mike, concluding:

Actually, it would be accurate to say we’ve known each other for a few hours out of those 30 years.

But we’re familiar with each other’s work. I don’t hesitate saying that at times Jack’s columns have been outstanding. And he’s also done some clunkers.

For example, I remember his lavish praise of a flashy Chicago cop named Richard Cain, who fed stories to Mabley. Reading those columns, you’d think Cain was the greatest sleuth since Sherlock Holmes.

It turned out that Cain was secretly employed by the crime syndicate. He went to prison, became Sam Giancana’s bodyguard and was finally bumped off.

Was Mabley’s praise of Cain a “shoddy breach of journalistic ethics”? I never thought so. I assumed it was simply a mistake in judgement. An error. So, he blew one.

It happens, Jack. Or maybe you forgot.

So no love lost between Mike Royko and Jack Mabley. Otherwise, rather than writing a whole column accusing Royko of “shoddy journalistic ethics,” Mabley would have talked to his old teacher friend, then called Mike up to discuss the issue privately.

And every time Mike Royko looked at Walter Jacobson, he probably saw Jack Mabley standing behind him.

Who’s the Boss

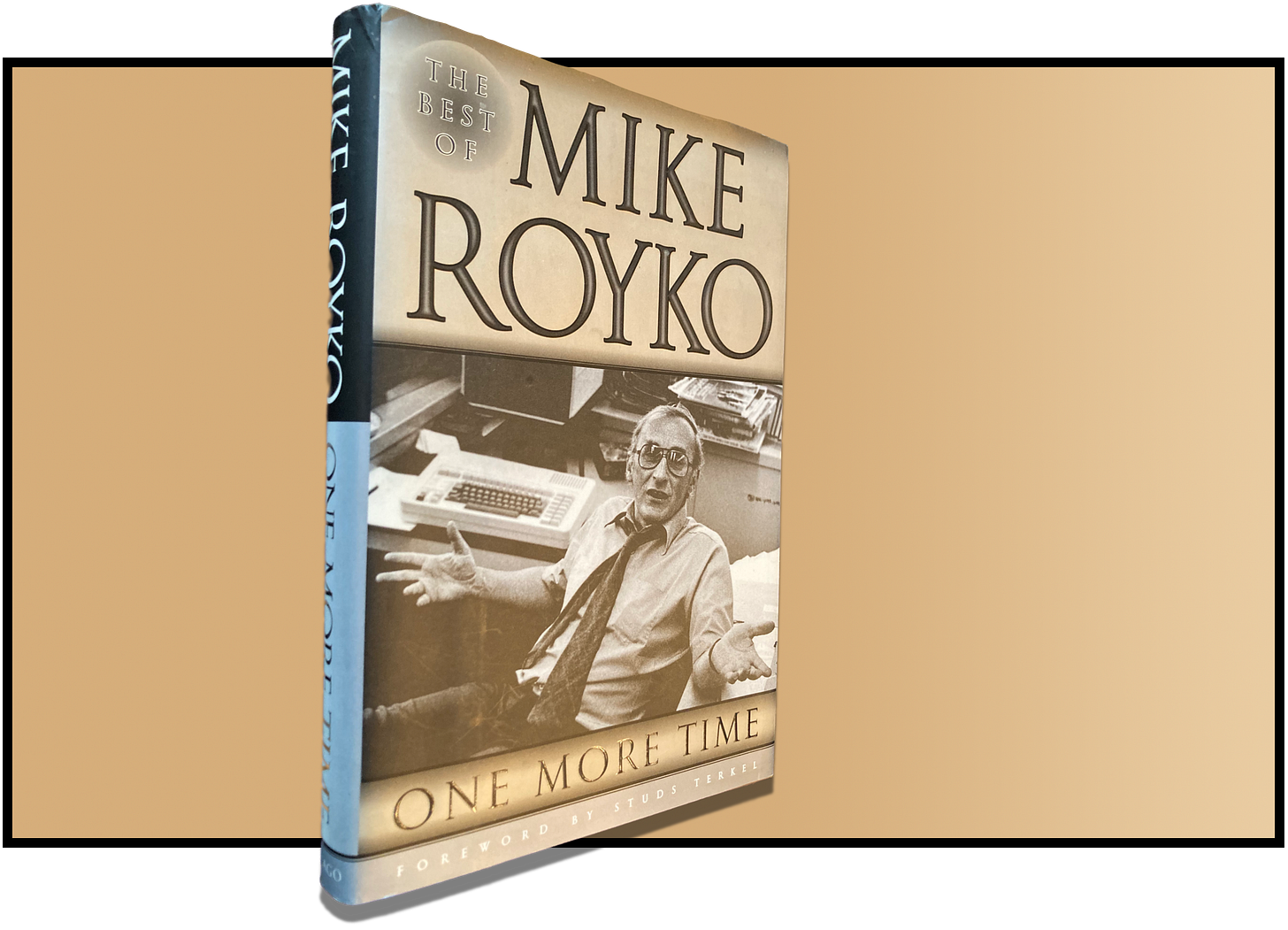

Before we get to Walter’s TV career, let’s look at one more intersection between the two men in newsprint that probably pissed off Mike Royko. This involves the debut of Royko’s masterpiece, Boss. As anyone reading here knows, Royko’s most lasting legacy is his 1971 biography of Mayor Richard J. Daley.

Boss, while fabulous, is not the most exhaustive look at Daley. For that, Chicagoans would have to wait until 2000 for Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor’s American Pharaoh. Len O’Connor’s Clout is also more detailed than Boss, but came out five years later than Boss, in 1975. So as Mike Royko’s first book went on sale, he wasn’t quietly hating any of those authors.

What about Sun-Times sports columnist Bill Gleason, who wrote the first biography of Mayor Daley, Daley of Chicago? Mike must have felt competitive with Gleason, since his book came out in fall of 1970, just a few months before Boss. How annoying for a sports columnist to put out the first Daley biography! How embarrassing would it be if the sports columnist’s book was better?

Gleason’s book is even surprisingly similar to Boss in some ways. Off the top of my head, I don’t think Boss includes any big facts that Gleason missed. Because here’s the thing: If your only reading on Mayor Daley is Boss, you may think it revealed a lot of Daley secrets. Not so. The grandeur of Boss is how Mike wrote about facts that were already known to Chicago politicos.

If Mike was irritated by Gleason’s book, perhaps his pique passed quickly—because Daley of Chicago was virtually ignored as Chicago media breathlessly awaited Boss. As Gleason’s bio hit bookshelves, everybody knew Royko’s version was going to the printer’s. Even Gleason’s own paper, the Sun-Times, didn’t run a series of excerpts, and didn’t tout his Daley bio on the front page. Which is nuts. The Sun-Times gave Gleason a nice book review in November 1970, and that was it. The Daily News and Tribune didn’t even review Daley of Chicago.

The Daily News and Sun-Times were, at this point, both owned by the Field family. Did the larger company decide to mostly ignore Gleason’s book, to give Boss an even bigger reception? Beats me. But it’s easy to trace in the papers that Gleason got one review, he was on a few local talkshows, and a couple of months later, Boss took over the bookstores and the world.

Bye-bye, Daley of Chicago. I feel awful for Bill Gleason, really. His book isn’t Boss, but it’s quite good.

The coming of Boss was mentioned in the Chicago press here and there in advance, but the real publicity blitz began the weekend of March 13-14, 1971, with a giant spread in the Daily News weekend arts section, Panorama.

It wasn’t just a review. As Panorama’s headline proclaimed, it was “A special report on Mike Royko and his new book ‘Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago’”.

Panorama’s “special report” on Boss included a review by big shot New York City columnist Jimmy Breslin, who wrote:

“It is the best book ever written about a city in this country. And perhaps it will stand as the best book ever written about the American condition at this time.”

Which is not hyperbole.

The March 1971 Boss release was not random timing. That put Boss in hands for the height of Mayor Daley’s fifth mayoral election campaign, this time against Richard Friedman—amateur politician, former BGA director, and Democrat-turned-Republican mayoral candidate. (You’ll be able to read an account of that wild campaign here in the future Part Three of my continuing series, The Great Reporter Rebellion of 1971. Why not subscribe for FREE and make sure you get that in your emailbox too?)

Everyone knew Mayor Daley would win, of course. But it was a fun campaign, with Friedman calling Mayor Daley “the great destroyer” of Chicago. Thus, it made absolute sense that the Tribune would run an exhaustive analysis of Daley’s life, career and mayoralty on March 28, 1971 in its Sunday Magazine, a piece nearly as long as a short book.

However, as we know, Mike Royko hated the Tribune—he once said reading the paper made the hair on the back of his neck stand up.

We also know Mike Royko hated people who worked for any paper competing with his own.

So we know there’s a good chance that Mike Royko found it truly galling for the Tribune to run a mini-biography of Mayor Daley two weeks after the official debut of his own full-length real biography.

And the Tribune’s approximately 10,000-word coverage of Mayor Daley was written by none other than….Walter Jacobson!

“Everybody who’s been a reporter for 10 years in this town has dreamed of doing a piece on Richard J. Daley,” Walter was quoted in the Sunday Magazine editor’s note. “I’ve thought about it every day of my journalistic life. And for the serious reporter it can’t be just a dream—it’s a responsibility.”

Imagine Mike Royko snorting over that. No wonder Mike loved to insult Walter Jacobson’s knowledge of Chicago politics. Recall Royko’s first slap at Ald. Marty Oberman: “In general, Oberman acted like a Walter Jacobson who actually understood what was going on.”

Given Royko’s competitive nature, my guess is he despised Walter’s mini-bio of Daley on principle for showing up during the premiere of Boss. I wonder if Mike might have even worried that Walter’s piece would keep some people from bothering to pay for a book about the same topic.

It’s instructive to compare Walter’s mini-bio with Boss. Walter’s piece covers all the basic Daley milestones and issues, and I see nothing objectively incorrect. But his tone is laudatory and awed overall, even though he mentions Daley’s downsides.

“When Daley took over, Chicago was sitting still,” writes Walter. “And he began, in fact, to build a vital, dynamic and beautiful city, which in 16 years has become the industrial and mercantile heartland of America, muscle and guts of the nation.”

Mike, on the other hand, never mentions something good about Daley without adding something else truly awful:

“Wherever he looks as he marches, there are new skyscrapers up or going up. The city has become an architect’s delight, except when the architect see the great Louis Sullivan’s landmark buildings being ripped down for parking garages or allowed to degenerate into slums.”

Here’s one particularly perfect side-by-side—a description of Mayor Daley meeting with people in his City Hall office.

WALTER

Mayor Daley sits people down in front of his large mahogany desk and he asks them what they want. Then he listens. By not saying much, he compels them to say a lot; he not only absorbs information that way, but he gauges exactly how much his visitors know.

If he is intimidating, he doesn’t mean to be. Rather, he is weighing his considerations, keeping his options open—deciding which of the special interests and which of the community leaders he can use as political resources in behalf of his goals and programs. He also is deciding how to neutralize or bypass opposition, or to wait it out.

He sits there erect, almost always in a blue suit and white shirt, his arms folded across his bulk, one hand under his chin, his mouth occasionally twitching—committing himself to nothing. He is slow, deliberative and uncommonly cautious. Only when he knows who is thinking what, does he begin to form his coalitions and build his consensus. And then, thru a deft mixture of power of his two offices [mayor and chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party], he gets the bureaucracy moving the way he wants it to move.

MIKE

He will come out from behind his big desk all smiles and handshakes and charm. Then he returns to his chair and sits very straight, hands folded on his immaculate desk, serious and attentive….Now it’s up to the [community] group. If they are respectful, he will express sympathy, ask encouraging questions, and finally tell them that everything possible will be done. And after they leave, he may say, “Take care of it.” With that command, the royal seal, anybody’s toes can be stepped on.

But if they are pushy, antagonistic, demanding instead of imploring, or bold enough to be critical of him, to tell him how he should do his job, to blame him for their problem, he will rub his hands together, harder and harder. In a long, difficult meeting, his hands will get raw. His voice gets lower, softer, and the corners of his mouth will turn down. At that point, those who know him will back off. They know what’s next. But the unfamiliar, the militant, will mistake his lowered voice and nervousness for weakness. Then he’ll blow, and it comes in a frantic roar:

“I want you to tell me what to do. You come up with the answers. You come up with the program. Are we perfect? Are you perfect? We all make mistakes. We all have faults. It’s easy to criticize. It’s easy to find fault. But you tell me what to do.”…..All of which leaves the petitioners dumb, since most people don’t walk around with urban programs in their pockets.

Walter in TV Land

Now on to Walter’s move to TV, because broadcast news itself became another reason for Mike Royko to dislike Walter Jacobson.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Robert Feder explains, “Print journalism was still the top dog, and it still set the agenda, and it was still where the serious journalism happened. But broadcast news came into its ascendancy, and over a period of time it became dominant.”

In his memoir, Walter himself points to the print-broadcast clash as another likely source of Royko’s animosity:

“My conjecture is that like his fellows in print, Royko begrudges us our salaries and the fact that more people watch the news on television than read in the papers.”

Walter’s memoir describes the scary decision to jump from Chicago’s American to WBBM-TV news at the end of 1963, lured by former American colleague John Madigan, who’d become Ch. 2’s news director:

“I was intrigued by his suggestion, though torn between the familiar that I loved and the unknown. TV news was gaining momentum, impact, influence, and stature. It was today instead of yesterday, new instead of old, fast instead of slow, restless and urgent. All in all, it was pretty appealing, and it offered added incentives of better pay and some celebrity.”

Walter got in on the ground floor. The 1960s saw the rise of TV news over newspapers, which accelerated in the ‘70s and became the new norm by the ‘80s.

“The conflict between print and broadcast manifested in many ways,” says Feder. “This was one of them. I always thought of Walter as a stand-in for the overall resentment of print journalists led by Royko against what they saw as the silliness and the excesses of TV news. And he was able to conflate that with Walter personally, so that his descriptions of Walter were meant to condemn the whole industry.”

So envy and fear probably played a part in Royko’s side of the feud.

Envy of the unbelievable paychecks pocketed by TV news people.

Fear as TV news helped drive the decline of newspapers, afternoon newspapers in particular.

Royko’s beloved Chicago Daily News would go down in 1978, a victim of that process. He saw the paper’s ultimate demise coming for years. After all, the Daily News’ competitor, Chicago Today, folded in 1974. Royko biographer Richard Ciccone notes that concern over the Daily News’ future may have tipped Royko’s decision to turn down offers to go big-time nationally in Washington:

“My column is needed here,” he told More magazine in 1975. “If I left the Daily News circulation—if what they tell me is true—maybe it wouldn’t sink the ship, but it sure as hell would be listing pretty badly….Do I want that on my conscience the rest of my life—that I was the last nail in the coffin? Who the fuck wants that? ‘Yeah, he was a really great newspaperman; he really helped put the paper under.’

But even Royko wasn’t enough to save the Daily News.

TV news audiences grew through the 1970s as afternoon newspaper circulation plummeted. People “weren’t buying ‘em anymore,” Feder points out, “because they weren’t able to get [newspapers] out into the suburbs physically in a timely way,” which “gave rise to afternoon and early evening newscasts”. Soon, TV news became cheaper to produce, and advancing technology expanded it with mini-cams that increased live coverage and remote reports.

Channel 5 news established early dominance here with anchor Floyd Kalber in the ‘60s, before being challenged and surpassed by Channel 7’s “Happy Talk” news team. Channel 7’s ratings grew thanks largely to clever advertising, says Feder. The Channel 7 marketers earned their salaries, as you’ll see in the 1968 spot below.

(Younger Readers, that promo starts with a parody of newsreels shown in movie theaters during the 1930s and 40s, before television. I mention that in case you think 1960s TV looked and sounded like a 1930s newsreel. No; 1960s TV viewers thought the newsreel effect was funny and old-fashioned. It’s true, though, that most people were still watching on black and white TVs in 1968, with lousy reception from an antenna on their roof.)

Then, in 1973, Channel 2 premiered Bill Kurtis and Walter Jacobson and the station’s fortunes quickly changed. Channel 2 was also propelled by tech, notes Feder. “It is not a coincidence that the first mini cams were used by Channel 2 in Chicago as this new format was getting underway,” he says.

Though four years younger than Walter, Bill Kurtis played the serious, authoritative partner with Jacobson as the irrepressible upstart. If they were the Smothers Brothers, Bill would play the bass. (Younger Readers, I too was not around to watch The Smothers Brothers Show, but they were objectively hilarious from any time period’s POV.)

Bill and Walter walked in when Channel 2’s ratings were in a musty, dank basement with a dirt floor. A crawl space, really. As we covered in Part Three, Channel 2 promos trumpeted that Bill and Walter were real reporters, not just news readers. The station emphasized that schtick by placing the anchor desk in front of the Channel 2 newsroom, with work at least supposedly going on behind them—a feat never before attempted in TV news.

Here’s a fabulous promo from 1975—different than the one in Part Three, btw, if you think you’ve already seen it.

Channel 2’s dynamic duo started elbowing their way upstairs right away, first passing Channel 5’s venerable but boring Floyd Kalber who’d been hanging out in second place…

…and tagging the first place Channel 7 Eyewitness News Team just five years later. The holly jolly Eyewitness News Team had been smiling firmly in first since 1972, spreading their jokey format to other local ABC stations across the nation. Here they are in one of several staged “encounter group” games from a 1972 ad series. You should see the one where they whack each other with giant inflatable gloves.

Bill and Walter shoved Fahey Flynn and friends out of first place with the May 1978 sweeps ratings. They were done getting beaten by a bunch of guys in sweatpants playing encounter games. Channel 2 ran the full page ad below in both remaining major dailies (Trib and Sun-Times) on June 28, 1978. The headline could not be more specific:

Nobody can stay #1 forever, of course. Bill Kurtis left for a few years in the ‘80s for network news, including co-hosting the CBS morning show. He would also form his own production company and narrate hundreds of documentaries, then pop up as the voice of “Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me!” on NPR. Walter moved to Fox 32 News in 1993, staying until 2006. For 2010-2013, Bill and Walter reprised their anchor teamwork on Channel 2.

But it doesn’t matter to newspapers which TV station is taking the most potential readers away from them. Even the third-place station had more viewers than the top circulation newspaper.

So Mike Royko rightly feared TV news overtaking print.

And he was only human to envy the money.

Man oh man did those TV guys make the big bucks, even then. And after his hardscrabble childhood, Royko was acutely aware of money. Remember, this is the guy who didn’t get to sit at his own kitchen table, in his own house, until he was 37 years old—even though he’d been the star columnist in the country’s second biggest city for several years already. Before that, young adult married-with-kids Royko was living in a basement flat or with his in-laws.

As the years went by, with TV news growing and Walter advancing to anchor and then star anchor, his salary skyrocketed compared to Royko’s. According to a 1974 Daily News feature on Chicago celebrity salaries, Mike made $51,000 that year while Walter made $55,000, just a year into co-anchoring Channel 2 news with Bill Kurtis. By 1977, Walter’s salary had jumped to $110,000—almost $600,000 in 2023 money.

It didn’t help that Walter often publicly wailed about his glorious salary. In 1978, Royko wrote an entire column about 41-year-old Walter’s latest salary complaint, at which point Jacobson was making $140,000. That’s almost $700,000 in 2023 dollars:

“You know local [TV] news was by and large ridiculed by print journalists, anybody who envied the money those guys were making and the notoriety they enjoyed,” seminal Chicago Reader press critic Michael Miner told me. “A lot of it was jealousy, it was inevitable, and Royko certainly made that acceptable. He put Jacobson on the radar as a figure of ridicule. Is it fair? Well, ridicule is probably never fair, but who made more money?”

Temper, temper

Another accelerant to the Royko-Jacobson feud: They both had a temper.

Royko, as we all here know, drank too much, got in bar fights, and received at least one DUI. Veteran Chicago reporter Ellen Warren met Royko on her first day on the job: “My first assignment was to cover Royko in traffic court where he was on trial for giving the bird to a police officer who had stopped him for running a light or a stop sign,” Warren told Ciccone for his bio.

Royko’s most notorious dust-up came in 1977, when he “wandered shortly after midnight” into a Lincoln Avenue singles bar, already drunk, per Ciccone. There’s more than one version of what happened next, but Royko definitely approached a table of several theater company members, and one woman claimed Royko “offered to buy her a steak,” writes Ciccone. “She said no. Then Royko and the five men began insulting each other.” The police report said Royko “picked up a ketchup bottle from the table, broke it and threatened those at the table.” Ultimately, Royko paid a $1,000 fine for disorderly conduct.

Now, recall from Walter’s memoir that he never talked to Mike about their fraught relationship:

“No bellying up to a bar for me with Mike Royko. He wouldn’t hear of it, and I’d be uneasy. He’s a grouchy guy. After a slurp too many, he turns treacherous, egging for a fight, too tough me.”

But Walter was also known for his moments, and his own DUIs.

“His outbursts in the Channel 2 newsroom have become as predictable as spitball-tossing in the Channel 7 newsroom,” wrote Tribune reporter Clifford Terry for Walter’s first big profile in the Tribune Sunday Magazine in 1977.

“You missed another one,” Walter told Terry several weeks into their interviews. “Last night I broke the door to the newsroom. It had to do with my having to do promotions and being dragged around like a robot. I opened the door with a little more ‘strength’ than I should have, and it crashed against the wall and the molding fell off.”

That year, in fact, Walter was suspended for two days “after an off-the-air shouting match that witnesses said humiliated an associate producer of the 10 p.m. news,” as Sun-Times TV critic Bill Granger reported, quoting a “highly placed Channel 2 source”: “Walter has become obstreperous, arrogant and undisciplined. He is now disrupting the news operation with his frequent outbursts.” The spat was over how the evening’s Perspective was going to be illustrated.

In 1986, Tribune INC. gossip columnists Michael Sneed and Kathy O’Malley wrote “you oughta hear TV news commentator Walter Jacobson when he gets in an INC. snit! His voice was booming. His little body must have been shaking with rage. You should have heard the things he threatened to do to INC. ‘I’ll ruin you. I’ll destroy you. If anybody knows how to do it, I do. I’ve been doing this for 20 years, and I’m better than anybody at it. And I’ll do it if you print one more incorrect item in INC. without calling me first.’ And all because we debunked one of his commentaries without calling him. And guess what, folks? INC. didn’t even mention his name nor say the item was even based on a TV commentary! Hmmmmm. Isn’t Walter cute when he gets mad.”

Walter was back in INC. in 1992 for reportedly throwing a book at “a newsroom staffer’s head….Walter’s version: It was simply a matter of his producer ‘tossing a book over a divider’ and Walter ‘tossing it back.’ What a relief to learn that it was just one of those Good Walter light-hearted newsroom book-tossing incidents, and not one of those Bad Walter tantrums.”

In 1994, Robert Feder reported that viewers heard Walter exclaim, “Oh, fuck you!” to an off-set director as the sports anchor finished his report. “A million things were happening all at once, and I just snapped for an instant,” Walter told Feder.

We should also note that Mike and Walter were both obviously under tremendous pressure in high-profile, demanding jobs.

“Royko suffered from debilitating fits of anxiety and self-doubt,” writes biographer Ciccone.

At Royko’s 1997 memorial service at Wrigley Field, Studs Terkel told Jonathan Eig that Royko continued writing five columns a week “not because he had to or even wanted to, but because he could not bring himself to do less.”

“He was possessed by a demon,” Terkel told Eig. “A demon called passion, a passion to set things right. That demon—without it there would be no Mike Royko. But the demon takes its toll on a human being.”

Royko was also possessed by his competitive nature, as we’ve seen. Surely part of Royko’s drive to write five columns per week derived from Jack Mabley—who wrote six columns a week until a year before he retired in 1982 at age 65. In 1981, at 64, Mabley cut back to three columns weekly. In his column announcing the change, Mabley claimed he’d written 8,641 columns at that point— “Six columns a week, 48 weeks a year, for 30 years.”

And Walter?

“I’m under a lot of pressure,” Walter told Clifford Terry in 1977. “I mean, my job has destroyed my family. I’ve lost 20 pounds in the last year. I’m a nervous wreck. I have an absolute death fear. Heart attack. I feel I’m not gonna live to be 50 years old because I don’t think a body can take the punishment mine does, meeting these deadlines. I think a lot about changing my life completely. Getting out.”

Geez, if they hadn’t been enemies, these two guys could have started a support group together.

Re the DUIs: To be fair, it seems like everybody got DUIs back then, like some sort of Silent Generation Scout badge. For instance, 20th century Chicago celebrity Irv Kupcinet, Chicago Sun/Chicago Sun-Times gossip columnist for decades, got arrested on a DUI in 1958 in Los Angeles. But it wasn’t played up as a big scandal, even by the competition. Kup was acquitted, while his companion Mrs. Dodge paid $100 for her own intoxication. The acquittal only got this much space in the American, on a back page, because the judge dissed Chicago and Kup “rose to his hometown’s defense”. Read to the end for that great exchange:

I mean, remember how funny Cary Grant’s drunk driving scene was supposed to be in North by Northwest? Just saying. Again, Younger Readers, it’s just what happened.

It’s 1981, do you know where Mike and Walter are?

In 1981, Mike Royko’s feet remain firmly planted on the pinnacle of Chicago journalism, nearly 20 years into his columnist career. We don’t have to go over any of Mike’s work that year to make the point. You know he is the bomb in 1981, because Mike Royko is always the bomb.

What about Walter Jacobson? In 1981, Walter is as close to being Mike Royko’s equal in professional stature in Chicago as anybody else would ever get. That, in itself, is an accomplishment.

Even in 1972, before Walter was an anchorman, he was included with Mike among the Chicago journalism giants in a massive news story now shockingly lost to history.

A former sidekick of Abbie Hoffman’s planted time bombs in safe deposit boxes in three downtown banks. The bomber sent warning letters to Mike Royko at the Daily News; Jack Mabley at Chicago Today; Tom Fitzpatrick at the Sun-Times; and Walter Jacobson, then a Channel 5 reporter. The bombs were all safely disarmed, but talk about a story! (For more on the time bombs, see THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 here, here, here, here, here, and here; and see Mike Royko 50+ Years Ago Today here, for the column where Mike answers the bomber’s letter.)

And there’s more.

In 1978, when serial killer and clown John Wayne Gacy got a prison guard to smuggle notes out of jail, the reporters he wrote to were Mike Royko and Walter Jacobson. (Walter would later get an exclusive interview with Gacy, and win a lottery for seats to observe his execution.)

When Chicagoans wrote in names on their ballots for everything from mayor to school superintendent, the only other media person who reliably got a vote besides Mike Royko was Walter Jacobson. For Michael Bilandic’s 1977 special election to replace the recently deceased Mayor Daley, Mike got two votes to Walter’s one—though dead Mayor Daley beat them both with six votes.

Looking slightly into the future, for Harold Washington’s 1983 election, Mike got 17 write-in votes and Walter got 5. When the Washington Journalism Review polled its readers in 1985, Mike Royko was named the country’s best newspaper columnist, and Walter Jacobson was named Chicago’s best TV news anchor.

But back to our focus year, 1981, and the present tense.

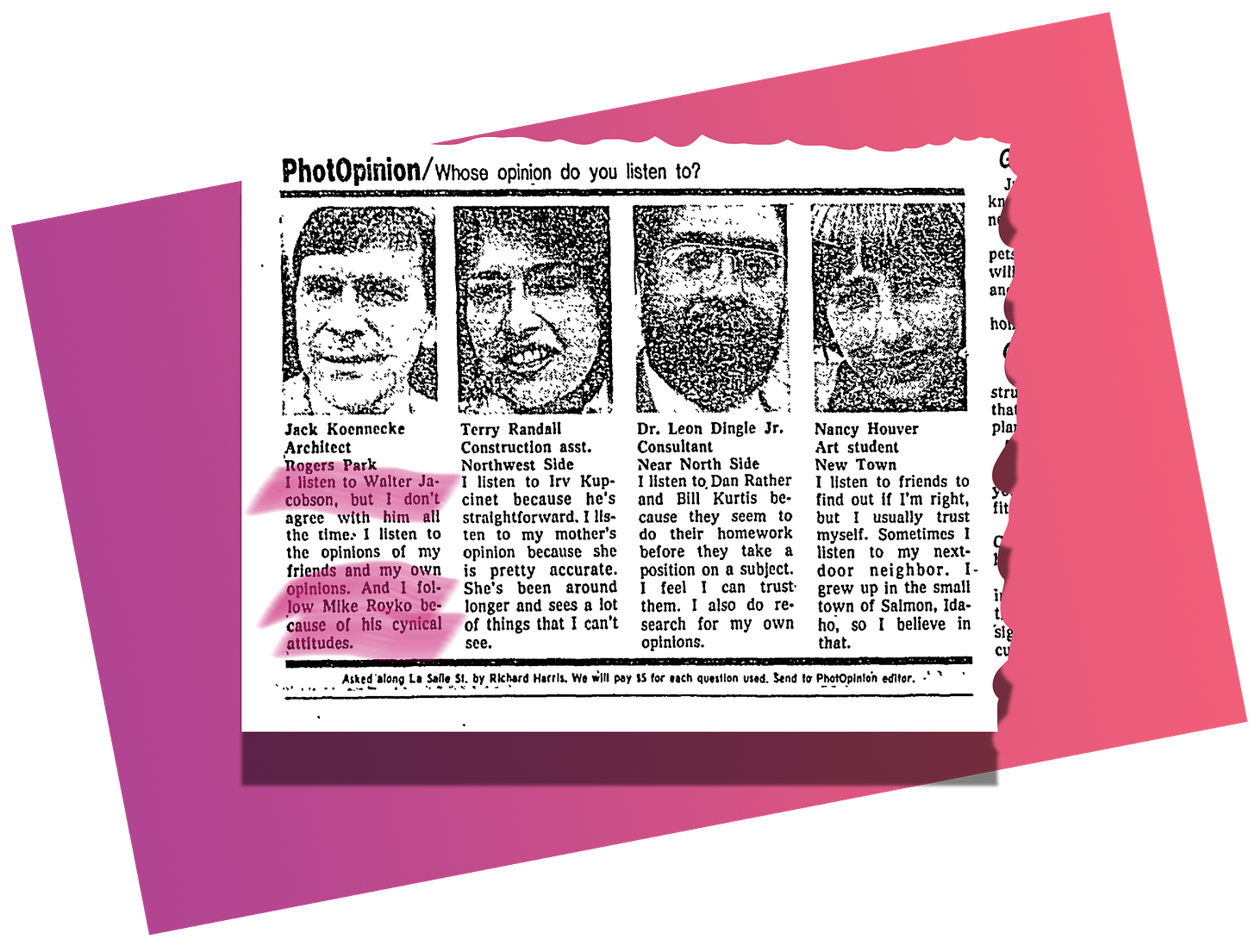

Who do people listen to in 1981? Mike and Walter.

When a suburban Chicago man creates The Very Unofficial Jane Byrne Coloring Book in 1981, based on the city’s then-incumbent first woman mayor, he features three media celebrities—including of course Mike Royko and Walter Jacobson.

Note that the coloring book’s instructions for Mike’s picture below say “Color him pinko.” That’s because in 1981, Mike Royko is still the big liberal columnist in town, so the joke is to call him a “pinko,” a now underused alternative term or amplifier for “communist,” as in “You commie pinko you.”

The coloring book’s third journalism celebrity, btw, is naturally Sun-Times gossip columnist Irv Kupcinet. I’ve included a photo insert of a 1960s Kup, for Younger Readers who lack an idea of the scale of Kup’s famous nose.

In August 1981, the Tribune runs a lengthy article headlined “Question of the ages: What makes us sexy?” Robert Redford and Bo Derek are top examples, but author Charitey Simmons also surveys Chicagoans about local sexy personalities. According to one respondent, “Wit, humor and an ability to laugh at life are what make WBBM-TV commentator Walter Jacobson and Chicago Sun-Times columnist Mike Royko sexy”.

I’m thinking Mike felt competitive with Walter in the sex appeal department too. According to biographer Richard Ciccone, Mike was keenly aware of looking older than his years and didn’t like it. Walter, on the other hand, was always being quoted on his latest work-out regime. Walter kept trim, he kept all his hair, he was already five years younger anyway, and he drew consistent attention from the ladies:

1981 is a big year for Walter. He wins his 8th consecutive Chicago Emmy for TV news commentary, at a swank awards show hosted by comedian Robert Klein at the Michigan Avenue Chicago Marriott.

Here’s a representative 1981 full-page ad from Channel 2:

How is Walter and Mike’s relationship leading into November 1981?