Mike Royko 50+/- Years Ago Today: The House on Sioux Leads to Lake Shore Drive

The Life and Death of High-Rise Man, Part Five

To access all site contents, click HERE.

Why do we run this separate item, Mike Royko 50+ Years Ago Today? Because Steve Bertolucci, the hero of the serialized novel central to this Substack, lived in a Daily News household—meaning the Bertoluccis subscribed to the Daily News. Back then everybody read the paper, even kids. And if you read the Daily News, you read Mike Royko.

This is the fifth installment of “The Life and Death of High-Rise Man,” a seven-part series on Mike Royko’s High-Rise Man columns mocking wealthy lakefront Chicagoans, and the life that led him to write those columns.

To skip the recap, scroll down to the larger version of this picture:

Part One: The Ascent of Royko traces Mike’s hardscrabble early life through the homes he lived in—and the life, in those homes, that led Royko to mock wealthy lakefront Chicagoans in 15 columns spanning almost 20 years. Mike called this new species of well-to-do Chicagoans “High-Rise Man.” Then, in 1981, he surprised everyone by moving to 3300 N. Lake Shore Drive.

Part Two: The Birth of High-Rise Man covers Mike’s first High-Rise Man columns, taking time to savor two of the most essential.

Part Three: Mike and Walter and Insults, Oh My! Mike’s searing High-Rise Man column on November 5, 1981 slams headlong into his lengthy feud with top Chicago TV news anchor and commentator Walter Jacobson. Here’s an initial look at Walter—and Mike and Walter—so the November 5 column will make some sort of sense to you.

Part Four: November 5, 1981 Mike’s November 5, 1981 column appears to be a very hot take on the independent lakefront liberals of the 43rd Ward, especially Ald. Marty Oberman and his constituent Walter Jacobson. But it’s really about Richard M. Daley’s successful 1980 campaign to move up from state senator to Cook County State’s Attorney. We’ll give you a backgrounder on the politics and examine the sizzling November 5 column. Careful not to burn your fingers.

Part Five: The House on Sioux Leads to Lake Shore Drive [YOU ARE HERE] Mike and his first wife Carol moved their young family into a darling house in Edgebrook. That house encapsulates why Mike would always identify with poor and working class Chicagoans, and scoff at wealthy lakefront residents as “High-Rise Man.” Mike’s departure from Sioux Avenue shows us what always made him tick—and finally drove him to a condo on Lake Shore Drive.

Part Six: Walter Strikes Back Walter Jacobson struck back soon after Mike’s November 5, 1981 column, instigating a monumental front-page Royko High-Rise Man column on November 22 that doubles as a 1980s Chicago time capsule—and essentially ended the High-Rise Man concept. Here, we prepare for that moment of truth by examining how the paths of Mike and Walter crossed and re-crossed through the middle decades of the 20th century—and then observe their biggest collision.

Part Seven: The Last High-Rise Man [COMING] Because there’s so much fascinating material to cover in Part Six leading up to Mike’s November 22, 1981 column answering Walter Jacobson, that 1980s time capsule of a column gets its own post here.

High-Rise Man Addendum: Bill Granger Weighs In [COMING] A few months after Mike and Walter’s dust-up, Tribune columnist Bill Granger revisited the issue in his own indelible way. To Granger, the question is: Does your past world disappear? You know what Faulkner said. Granger covers this age-old debate from a Chicago perspective.

The Life and Death of High-Rise Man:

Part Five - The House on Sioux Leads to Lake Shore Drive

In 1969, Mike and Carol Royko moved their family into a darling house in Edgebrook on the Northwest Side. We could glance at 6657 N. Sioux and move on, but this house has more to show us. Let’s look harder.

Per several online real estate websites, 6657 N. Sioux Avenue was built in 1930 with 2,358-square feet and four bedrooms. Bigger than a classic Chicago bungalow or workman’s cottage, but no McMansion. Mike Royko sold it in 1981 for $130,000—$458,811.84 in 2023 money.

Mike’s move to Sioux Avenue encapsulates why he would always identify with working class Chicagoans and snort at rich ones, leading him to make fun of wealthy lakefront residents in 15 “High-Rise Man” columns spanning nearly 20 years.

Mike’s departure from Sioux Avenue will show us what always made him tick—and finally drove him to a big condo on Lake Shore Drive of all places.

Once we’ve covered that ground, we’re ready in Part 6 to view the aftermath of Mike’s seminal High-Rise Man column from November 5, 1981, written soon after his move to the lakefront. That column is actually about the shifting Chicago politics of the time which led anti-Machine liberals to back Richie Daley for Cook County state’s attorney—but Mike just couldn’t resist popping a few zingers at his long-time target Walter Jacobson, a top Chicago TV news anchorman and commentator. Walter’s response would instigate Mike’s monumental front-page High-Rise Man column on November 22, 1981, a veritable 1980s time capsule that essentially ended the High-Rise Man series.

The house on Sioux, and how Mike got there

After a hardscrabble childhood, Mike Royko ended up in reform school, dropped out at 16, and finally earned his high school diploma at the downtown Central Y.

All that time, he was in love with Carol Duckman.

“We met when she was 6 and I was 9,” wrote Royko in his first column after Carol’s tragically young death in 1979. “Same neighborhood street. Same grammar school. So, if you ever have a 9-year-old son who says he is in love, don’t laugh at him. It can happen.”

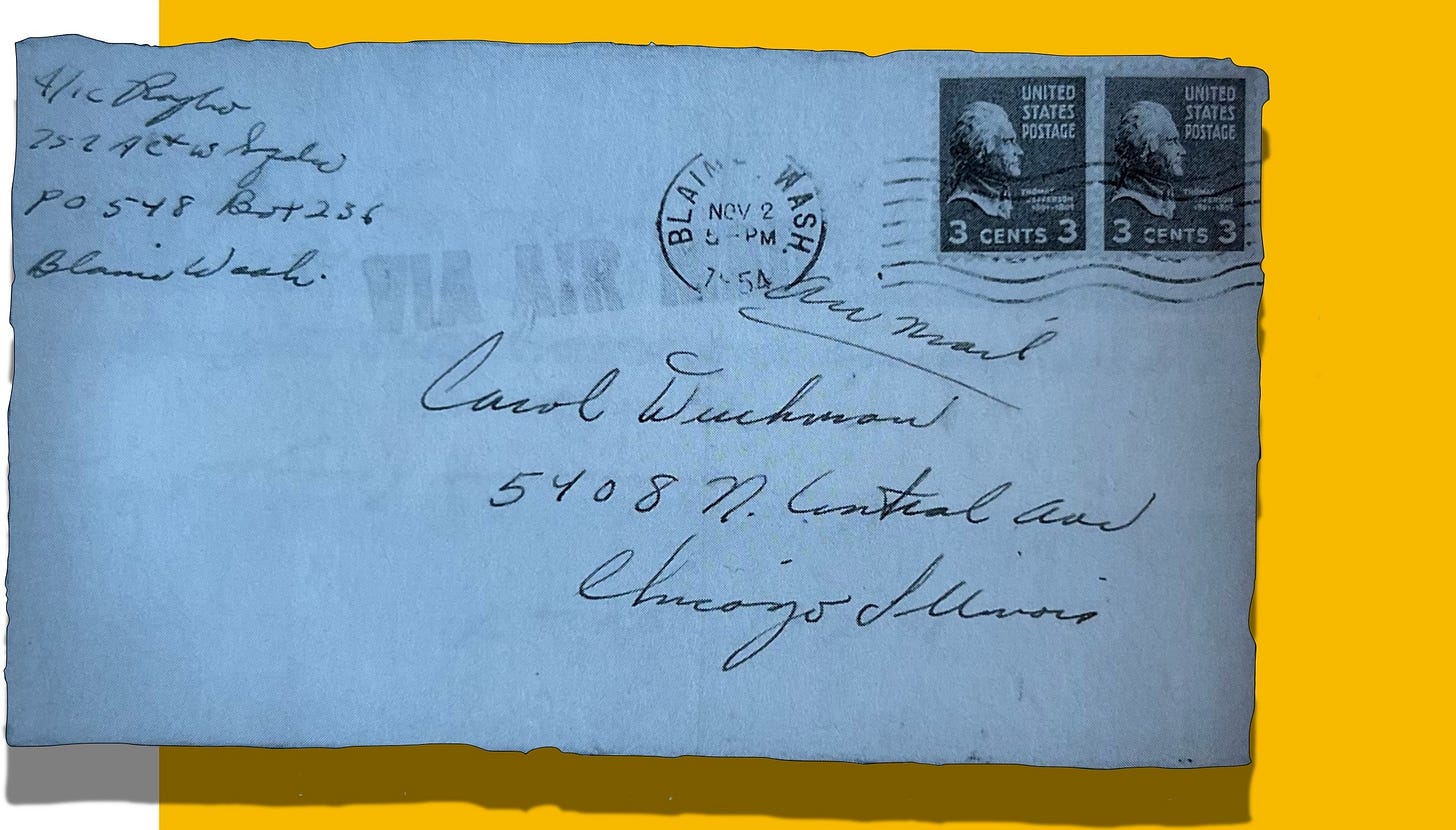

Mike started writing Carol in 1954 during his Korean War service as an Air Force radio operator, after returning from Korea to a posting at Blaine Air Force Base in Washington state. He’d been heartbroken as he left for Korea to hear that Carol had married another young man from the neighborhood, Larry Wozny. Then, as Mike returned for two more years of service stateside, he got something so many of us could use—a second chance. After just one year, Carol was divorcing Larry. Mike quickly confessed his love in writing and began wooing her. His letters literally fill a book, “Royko in Love,” edited by their son David Royko.

“My mom sat me down at 13 to have a serious discussion—which was odd—and told me that Dad was not her first husband,” David Royko told EPL Off the Shelf in 2011. “It just floored me. It wasn’t that she was ashamed or that is was a secret, but at that point even the mention of Larry would send Dad into a depression or a rage. He just never got over it. The jealousy was still there after all the years. She told me about the letters and how they won her heart, and she told me never to mention it to Dad.”

So the family never talked about the letters. Then, after Mike Royko died in 1997, David was going through some boxes when he discovered the letters, carefully filed in chronological order. “By the time he died he’d moved half a dozen times but had always kept the letters,” David told EPL.

Above all, the letters illuminate how wildly Mike was in love with Carol.

“Last night I was sitting in the mess hall, drinking coffee with a bunch of the guys when the ‘Dream’ [song] came over the radio,” reads one letter. “I was sitting back, listening to it and looking at the picture [of Carol] in my ID bracelet. I didn’t think I was creating any interest ‘til I looked around and all the guys were smiling. When they saw me look up they all busted out laughing and informed me that I really had it bad. As if I didn’t know. Baby, I have it bad. The love I feel for you can’t be described in words.”

About six months after Mike started writing Carol, he came home on leave and proposed. He hadn’t actually seen Carol since his deployment to Korea, nearly two years earlier. But his letters had won her heart. Carol accepted. Her diary entry from September 2, 1955 will melt your heart: “My baby came home at last. We’re in each other’s arms. I love him very very much. Ecstasy!”

The letters that followed after Mike’s return to Blaine were full of his dreams for their future life, a life he imagined in their dream house.

One night when he couldn’t sleep, Mike described lying in his barracks bunk for several hours: “I just smoked and dreamed about the future. Actually, they weren’t really dreams. Plans would be more accurate. Thinking about our house, our kids, our wonderful, perfect life together, and all the happiness we’ll have.”

The letters soon included Mike’s complaints about Air Force service keeping him from civilian life, where he could earn money faster for that future house. As he applied for a hoped-for transfer from far-away Blaine to the Air Force base then at O’Hare Field, Royko was planning to work for Yardley’s cosmetics, where his older sister Eleanor was a highly successful sales person.

“Everyone here had accepted me as a future Hemingway,” Mike wrote Carol from Blaine, “but everyone agrees that I’ll make a good salesman…I guess it’s cut and dried. You’re stuck with a salesman babe. Selling amounts to one thing—the ability to sell yourself to other people. If I can sell someone as wonderful as my wife on the idea of spending her life with an 8-ball like me, then I must be a salesman.”

Mike expected a good salary at Yardley’s. “As far as your job goes hon, if Yardley’s is going to pay as much as I think it will, you wouldn’t have to work after my discharge anyway,” he wrote one day. Later, he noted that an O’Hare transfer would be perfect because “I could get started in Yardley’s immediately.”

Here’s Mike’s final written word on the dream house, from December 4, 1954, not long before the transfer came through and the letters ended:

“If I get O’Hare we will be living as civilians, earning more money than most civilian couples and saving more than we expected. Besides that I’d be all set to manage [at Yardley’s] by the time I’m discharged and I’ll have to become a manager before the mortgage people would let us buy a house. Sweetheart, if I get O’Hare, we’ll be in our dream house right after my discharge.”

The transfer came through. Mike reported to the duty officer at O’Hare Field. Soon enough, he was discharged into civilian life.

But no, the young couple did not instantly move into their dream house. A long road to Sioux Avenue stretched out before them. Maybe that’s because Mike went into newspapers instead of sales.

At Blaine, Royko had started a little mimeographed base paper concentrating on sports, according to his roommate there. When Mike reported to the duty officer at O’Hare, he heard the base newspaper editor was leaving—and quickly claimed he’d been a reporter for the Chicago Daily News. Royko’s instant assignment to edit the eight-page O’Hare News apparently turned his thoughts away from Yardley’s after the Air Force and on to journalism, starting with a little Northwest Side biweekly neighborhood paper.

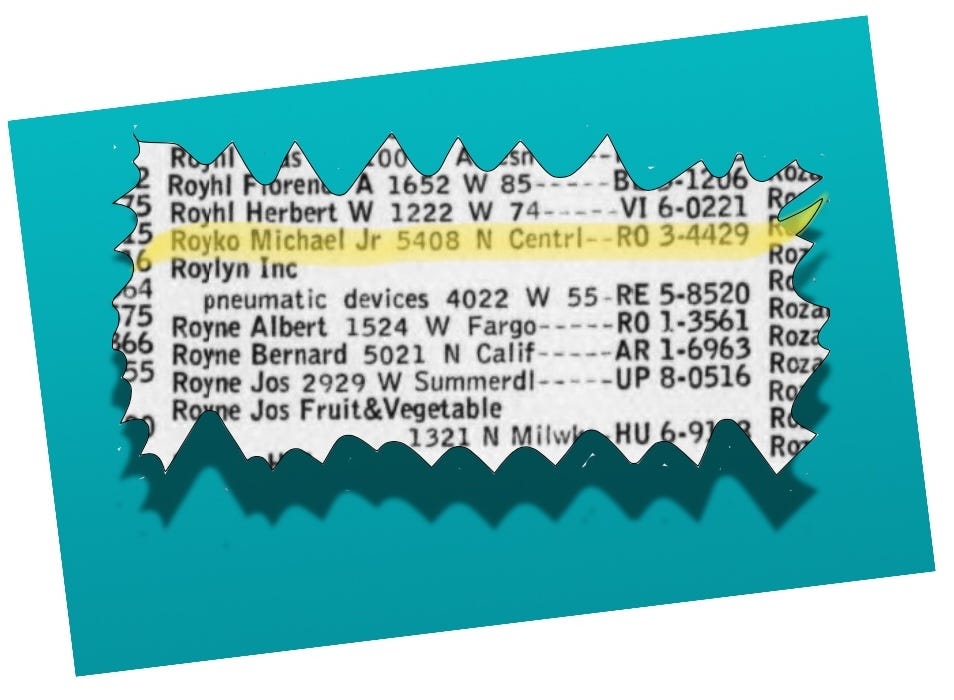

At first, the young married couple lived in a basement apartment—or “flat” in the Chicago terminology of the time. I can’t pin down the location because Mike was listed in the phonebook each year 1955-1959, but at his in-laws’ address. Why would Mike pay for a phone line at his in-laws’ house if he didn’t live there?

It sounds strange, given how frugal Mike was at this time, saving for the future. I have an idea, though. As noted in Part One, the AT&T corporation (American Telephone & Telegraph) controlled nearly all telephone service in the entire country until the Justice Department broke up the monopoly with an antitrust lawsuit resulting in a 1982 consent decree. AT&T was the original giant, evil, all-powerful corporation secretly controlling society. One phone company to rule them all, and one phone book per community to list everyone who could afford a phone. The listing itself was free.

People valued that phonebook listing. With no internet, the phonebook was often the only way to find anybody without a private detective. My theory is that Mike may have felt his own phonebook listing was crucial for professional purposes as he started out. But it was costly to set up service at a new address, and he and Carol may have been moving frequently at this point between cheap apartments. So they may have set up a line at the Duckman’s house, where they could be sure to get any message from Carol’s parents. I used my parent’s address for a while after college for similar reasons, and my own kids are still using my address as they often relocate. Got a better theory? Please share in Comments!

Can’t get enough Royko? Delve into the whole section. That’s where we go through Mike’s 1972 columns week-by-week, giving political, historical and pop culture background so younger and future readers can fully appreciate all the references and jokes. START HERE.

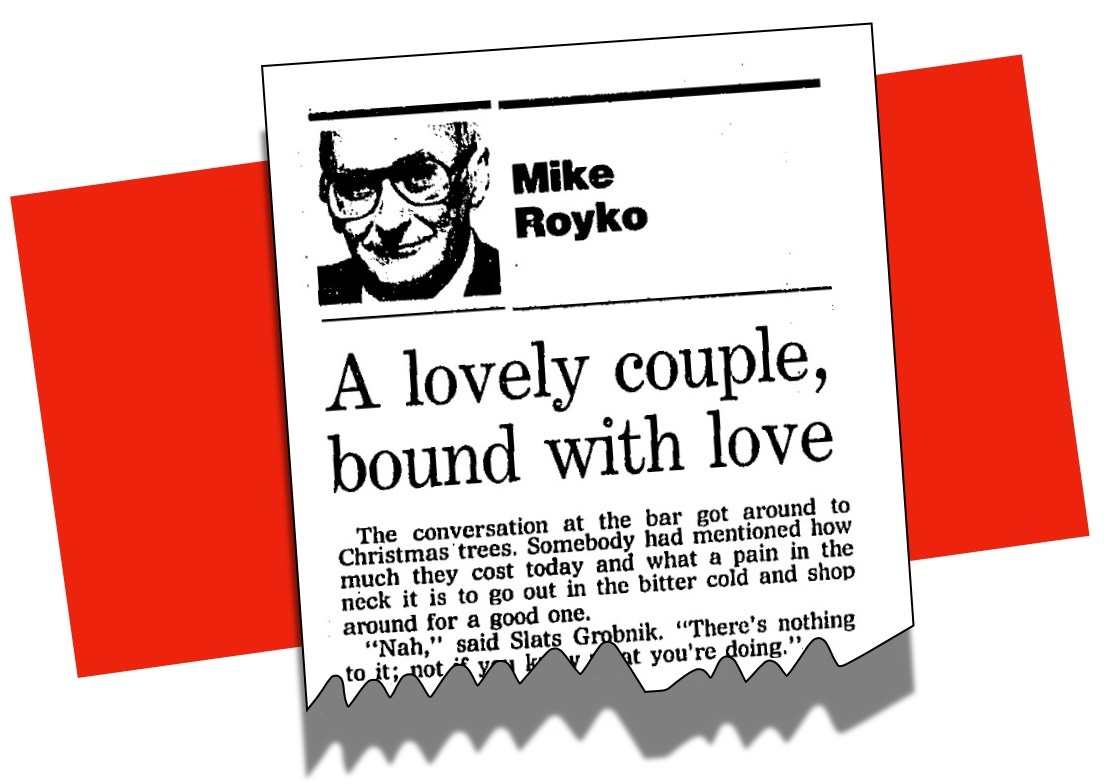

Anyway. Mike and Carol resided in “the dumpiest three-flat” in the neighborhood, as Royko described it via Slats Grobnik in a December 24, 1985 column:

Mike is at a bar when the conversation turns to Christmas trees. Slats recalls selling trees for his uncle in a vacant lot, when he learned “The secret of having the most beautiful tree you ever saw.”

Slats tells the barflies about a young couple who came looking for a tree on the cold night before Christmas Eve in the 1950s.

“He’s a skinny young guy with a big Adam’s apple and a small chin,” says Slats. “Not much to look at. She’s kind of pretty, but they’re both wearing clothes that look like they came out of the bottom bin at the Salvation Army store.”

The young marrieds aren’t dressed well for the weather, Slats explains, “So it’s easy to see that they’re having hard times with the paychecks.” They examine every decent tree on the lot, always quietly disappointed to hear the price.

“Finally, they thank me and walk away. But when they get out on the sidewalk she says something and they stand there talking for awhile. Then he shrugs and they come back.”

The couple negotiate for two awful trees, each with a whole side of scraggly brown branches and bare spots. Slats readily sells them both spindly trees for a pittance.

Then, on Christmas Eve, Slats walks past the couple’s building. He glances down at a pretty Christmas tree in their basement window. Slats knocks.

“They let me in,” Slats tells his listeners. “And I almost fell over. There in this tiny parlor was the most beautiful tree I ever saw. It was so thick it was almost like a bush. You couldn’t see the trunk.

“They told me how they did it. They took the two trees and worked the trunks close together so they touched where the branches were thin.

“Then they tied the trunks together with wire. But when the branches overlapped and came together, it formed a tree so thick you couldn’t see the wire. It was like a tiny forest of its own.”

Slats finishes with one of his/Mike’s distinctively simple but sharp observations:

“So that’s the secret. You take two trees that aren’t perfect, that have flaws, that might even be homely, that maybe nobody else would want.

“But if you put them together just right, you can come up with something really beautiful.

“Like two people, I guess.”

That story had been long-time family lore, says David Royko, who reposted the column on Facebook in 2023 after seeing it on reporter Bob Chiarito’s indispensable “Royko Is God” Facebook page—for which David gave thanks, and I second.

Later, Mike and Carol lived on the third floor of Carol’s family’s ancient Victorian house in Jefferson Park, reunited with their phone line—763-4429. A big Saturday night was playing cards with family. Often they’d sit on the Duckman’s porch singing folks songs, with Mike and his brother Bob playing guitar.

The Roykos eventually expanded to the Duckmans’ second floor as the family grew to include two young sons, David and Rob. Carol’s mom had developed multiple sclerosis and couldn’t navigate the stairs, so the Duckmans stayed on the ground floor. After the Roykos left for Edgebrook, the Duckmans also moved. The house was demolished for a two-flat.

So the Duckman home was a teardown, though no doubt comfortable and beloved. I picture the old Granville house, after Mary fixes it up all by herself. Cheerful but drafty. Plenty of idiosyncrasies, like a staircase post that comes off in your hand every time you grab it. Take away: The young Royko family would not have been living in such luxury that they’d be crazy to get their own place.

Still, Mike and Carol did not buy their own home—that dream house Mike wrote about in so many letters—until they’d been married about 14 years. And that’s even though the time period maps directly on the post-World War II homebuilding boom with its enviable mortgage rates.

Either Mike and Carol couldn’t afford a house, they didn’t think they could afford a house, or Carol preferred living with her parents. I asked David Royko to clarify.

“I’m 99% certain us living there was strictly practical,” David answered. “Dad, of course, being born in the Depression, was very money-aware. He was 21 and advising mom how to deal with a bank for a loan in one of the ‘Royko In Love’ letters.”

Makes sense. As we saw in Part One, Royko came from a family of poor/working class renters who probably lived in a basement flat when he was born. His parents never even sprang for their own phone, much less buying a house.

Mike’s parents’ business, the Blue Sky Lounge, dissolved along with their marriage after hard-drinking Mike Royko Sr. kicked Helen Royko bad enough to break her ribs.

Mike Sr. continued making what must have been a modest living with a little Southwest Side tavern, the Cullerton Inn.

Helen initially ran her own little tavern too, the Hawaiian Paradise at 845 N. Ashland, before opening a tiny neighborhood cleaning/tailoring shop. One of Royko’s most poignant columns recounts his mom’s long hours in the shop, living in an apartment in back.

That upbringing stays with a person, something those more than a generation removed from humble beginnings sometimes fail to entirely grasp. Tough times may pass on the calendar, but not so much in the mind.

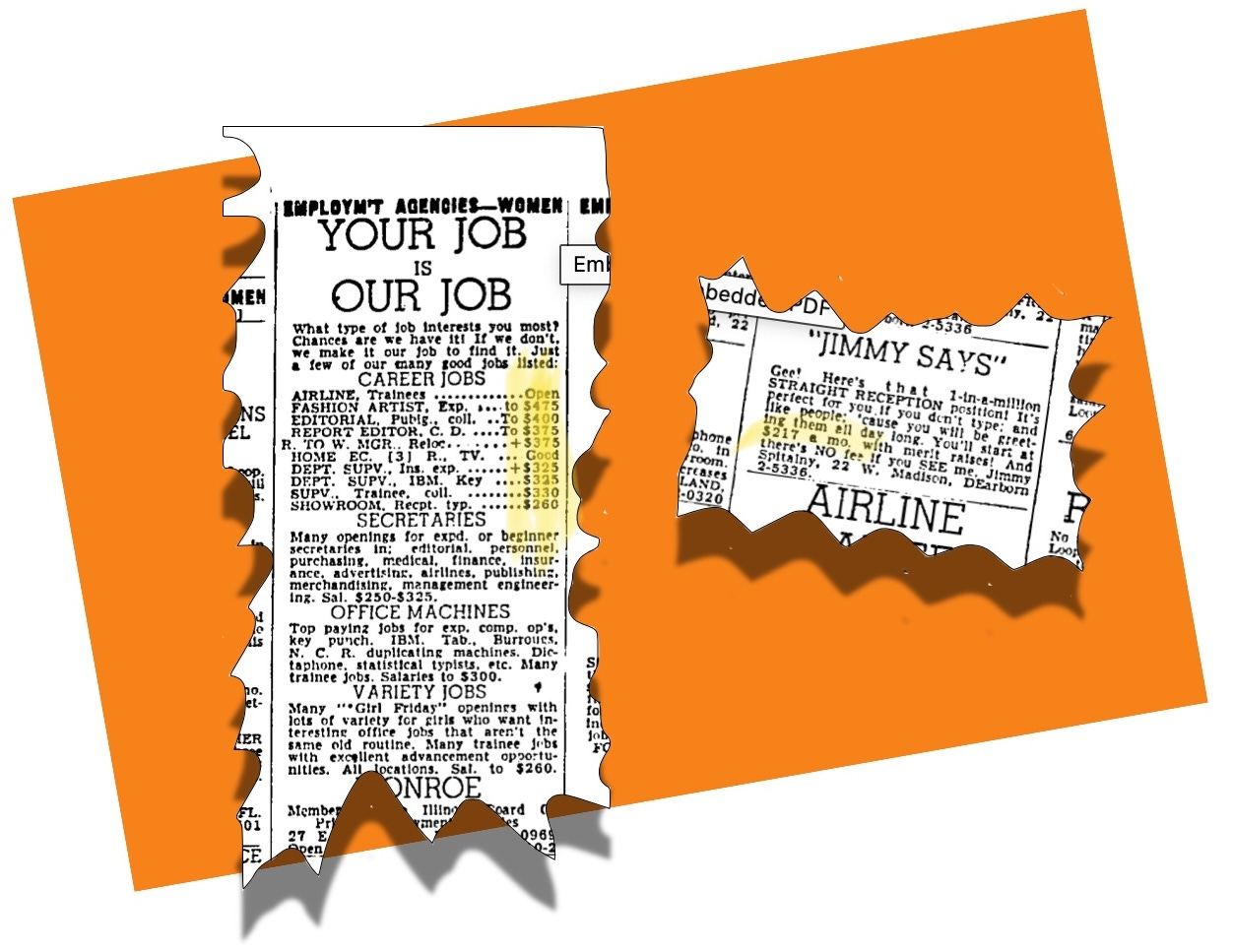

And Mike’s early pay was modest—first at the biweekly Lincoln-Belmont Booster, then City News Bureau, and finally as a rookie reporter for the Daily News. Through the ‘50s, Carol worked various jobs, often as a receptionist. She was pregnant with their first child, David, as 1959 began. Mike was making $105 weekly at City News, according to Richard Ciccone’s “Royko: A Life in Print.” That’s $5,460 annually—$58,000 in 2023 money per the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ inflation calculator.

We don’t know how much Carol made, but you can figure in those days—when job listings were separated by sex—that pay was low for any female-dominated job. The positions in the 1955 Tribune classified ads above go through an employment agency for jobs downtown, so they would have paid more than typical neighborhood offices. From here, we see a well-paid downtown receptionist earned from $217-$260/month—or $2,568 to $3,120 annually, which would be $29,500-$36,000 in 2023 dollars.

Mike also moonlighted in jobs like selling gravestones for his brother-in-law’s funeral home, later writing press releases for the annual Live Stock Exposition at the Amphitheatre and editing the Medinah Country Club newsletter.

On his way home from Medinah, Royko would stop at his sister Eleanor’s house in Elmwood Park, writes Ciccone. “Dorothy and I used to go to the Salvation Army and pitch in and buy Mike a dozen pairs of shorts and socks,” Eleanor told Ciccone. “We’d wash them and fold them just like our mother did, and I’d give them to him to take home. He and Carol didn’t have much.”

Royko finally made it to the Daily News just before David Royko’s birth later in ‘59, working his way to a $9,000 salary by 1963 when he was assigned to the County Building beat—$95,715 in 2023 money.

So by 1963, as he began his column and second son Rob was born, Mike was doing pretty well. These days, people with that income history would likely buy a home by the time their first child arrived, if not sooner. Instead, Mike and Carol spent another six years with his in-laws.

When Mike and Carol finally made the leap to home ownership in 1969, Royko had been the Daily News star columnist for several years. His first book of columns came out in 1967. He was making $25,000/year by ‘69 per Ciccone—$234,359 in 2023 money.

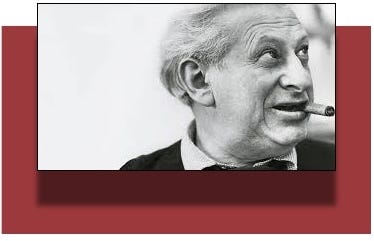

Here’s Mike at the kitchen table on Sioux—soon after moving in, going by the hair and glasses which are decisively still 1960s. He’s Chicago’s biggest journalism celebrity, finally sitting at his own kitchen table in his first house…at age 37.

“And I do believe that was the one and only time my father ever sat at the kitchen table wearing a tie,” David Royko commented when this picture was posted on Facebook.

So the road to Sioux Avenue was a long one financially, though we can see from Mike’s salary history that the final miles were perhaps more psychological for a kid used to living in basements flats, above a tavern, or behind a tailor shop.

Royko just never dropped a deep identification with, and some insecurity about, where he came from. As the reform school dropout tried to break into newspapers in the late 1950s, Chicago’s Front Page era was on its way out. Editors at all four major dailies were looking for people with college degrees. At the Daily News, Royko sometimes claimed he cut short his first job interview himself, because he was so intimidated by the news room that he didn’t think he could handle the job.

Later, we see the same mindset in both Mike’s relationship with Sun-Times editor James Hoge, and in his loathing for the Tribune.

Hoge was a tall blond handsome Yale grad, named Sun-Times editor in 1968 at the tender age of 33—basically a newspaper version of Robert Redford from “The Way We Were.”

Ciccone quotes Royko from a More magazine interview: “Hoge and I have never been friends, let’s say. Part of this, I think, is because we come from different social backgrounds. Hoge’s had all the breaks. Good looks, rich parents; he came to the Sun-Times right out of Yale. Me, I put in time at the City News Bureau first, then had to bust my ass to get my job. But I’m very impressed with Hoge….I don’t think I could ever picture myself going on a canoe trip with the guy or anything, but that’s irrelevant.”

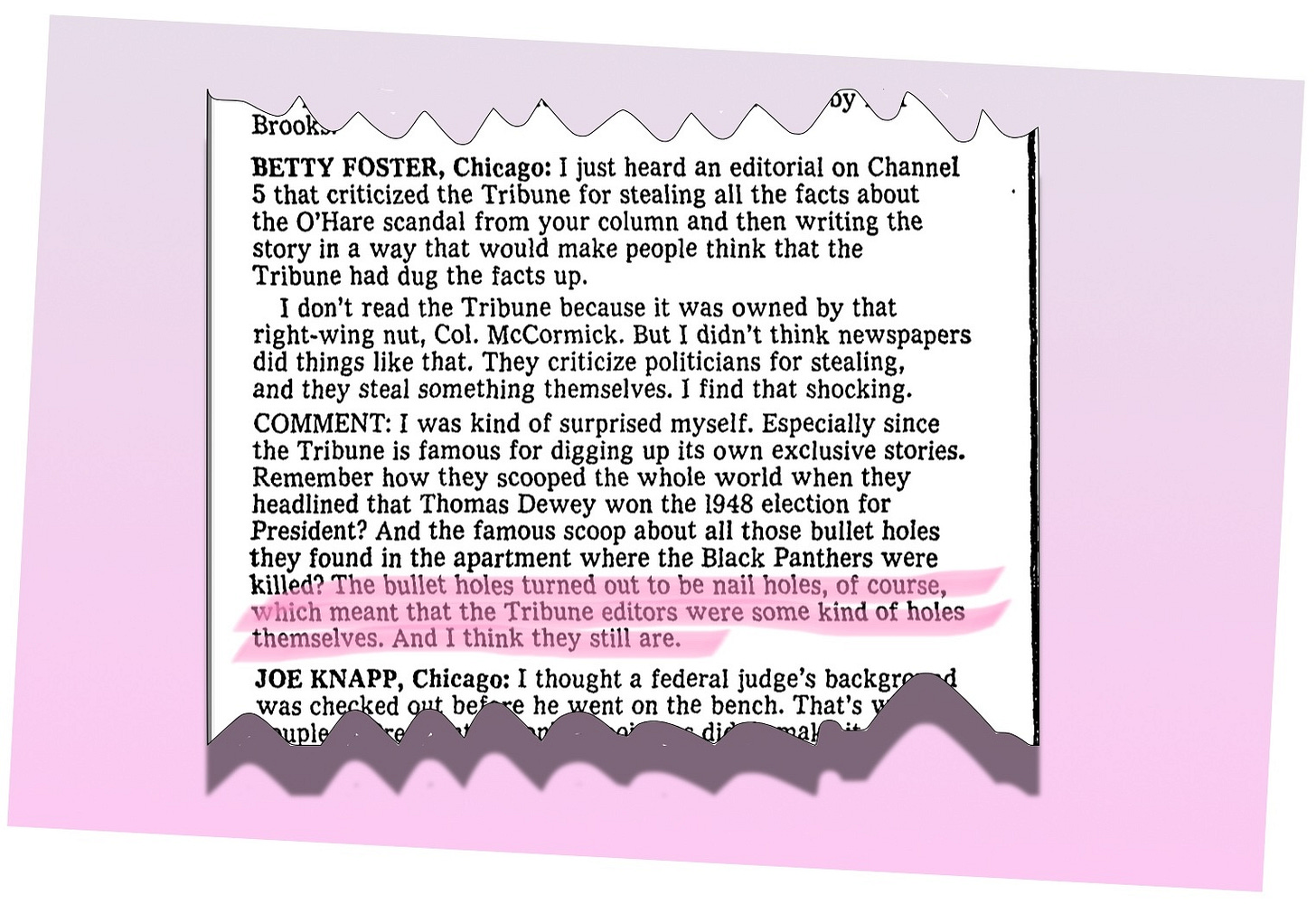

As for the Tribune, the early and mid-20th century version run by owner/publisher Col. Robert McCormick wasn’t entirely the rich, stuffy, Republican suburban newspaper its critics hated—but it was close enough.

The Tribune tried to lure Royko away from the Daily News in 1971, but he didn’t bite, Mike told Chicago author William Brashler for a terrific 1979 Esquire profile. “I couldn’t see myself working for the Tribune,” Royko told Brashler. “All my life the hair on the back of my neck stood up when I read the Trib.”

Royko wouldn’t work for the Tribune until 1984, when the city was down to two major dailies and Rupert Murdoch bought the Sun-Times. My current favorite Royko jab at the Tribune comes from Mike’s November 8, 1977 column in the Daily News, spurred by a reader’s letter. Savor the creative way in which Mike calls Tribune editors “assholes” without using the word in a family paper.

From Sioux to Lake Shore Drive

It took the kid who’d always lived within staggering distance of Milwaukee Avenue nearly 40 years to feel secure enough to buy a home—and almost 15 years after he began writing to his fiancee about their dream house.

Then why, how, in what world, does Mike Royko later end up moving to a gorgeous building on Lake Shore Drive?

Admittedly the 2023 photo above by VHT Studios, used for real estate listings, shows us a newly remodeled unit. Still, it’s a four-bedroom sixth-floor corner unit overlooking Belmont Harbor just to the south, in a building once owned by the Edith Rockefeller McCormick Trust and once home to Edith herself, daughter of John D.

So the question nags. Why?

As is so often the case, the answer has always been right in front of us.

Isn’t it always the most foundational person who we don’t really see anymore after a while, just like a real foundation?

We love to stop at a construction site and marvel as thick, strong walls of concrete are poured into forms deep in the ground. But once the structure is built on top and the landscaping put in place, we tend to forget about the foundation underneath, unless we need something down in the basement. We certainly forget that everything else would collapse without it.

Women of Carol’s age cohort, the Silent Generation, often seem to me even more overlooked than previous generations, overshadowed as they could be by both the men in their lives and the liberated women coming up just after them. Gloria Steinems aside, Silent Generation women generally worked plain old jobs rather than building careers, since few even considered college or a career as a possibility. During their most crucial young years, they were the last modern American women who were mainly encouraged and expected to think no further than homemaking, as long as economic circumstances allowed—only to find that vocation thoroughly passé once they were managing a house full of kids in a late 1960s-1970s world that prized youth, not middle-aged moms; and career women, not housewives.

Take Laura Petrie to illustrate the point. From 1961 to 1966, Laura Petrie was the quintessential American mom and housewife anybody would want to have or be, as you’ll see if you skip ahead to 5:15 in this episode of “The Dick Van Dyke Show”…

…but when Mary Tyler Moore returned to television with “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” in 1970, she didn’t play a slightly older Laura Petrie type character, still drinking coffee with Millie during the day and serving dinner every night on a perfectly laid table. In four short years, nobody wanted to be Laura Petrie anymore. Gorgeous Mary Richards and her wardrobe might get married someday, but first she was a TV news producer, even if her station was always in last place for comedic purposes.

I’m not pointing an accusing finger just at Mike here. This is simply how the world changed, what happened. Younger Baby Boomers and older Gen X’ers, I’m talking about many of your moms, and certainly mine too. I point longest at myself.

I’m ashamed to say I didn’t think much about Carol Royko until I read “Royko in Love,” a labor of love by son David, who clearly did see and appreciate his mom as much as he did his celebrated father. As David Royko notes in his eloquent introduction, “As much as [the letters] display Mike’s brilliance at an early stage, they are as much a testament to their inspiration—Carol.”

The letters themselves exist not just because Carol inspired them, but because it was she who saved them for the first crucial decades after they were written. Those letters make clear that Carol’s side of the correspondence was a lifeline that kept him going—reading and rereading her stories about life, work, and going to Chicago spots like the Edgewater Beach Hotel.

“I took all your letters, wrapped them into a bundle and put them into my bottom drawer,” Mike wrote after he returned to Blaine from his leave in Chicago. “Now I’ll start a file on all the letters received while we’re engaged. After we’re married I’ll start another file. I’ll always keep those letters—as long as I live.”

But he didn’t. So ironically, readers must meet Carol almost entirely through Mike’s words, with a few short diary entries of Carol’s added by David Royko. It’s enough, still, to see she was a multi-talented person who made a difference in the lives of everyone around her.

While Carol and Mike wrote each other, she worked several jobs and sang in a quartet. Before having children, she continued working as well as painting and modeling. Later, she built a darkroom in the house on Sioux. While raising the kids essentially by herself, Carol attended art classes at Roosevelt University and later worked on architectural renderings.

Too soon after the move to Sioux, Carol’s parents were confined to a nursing home. Now, in addition to caring for her own family, Carol “became an adored presence” at the nursing home, according to David Royko’s “Royko in Love” introduction. “She got to know the other residents, regularly stopping into rooms to say ‘hi’ to those who didn’t have family or friends who visited or were going through a rough patch, bringing little gifts for everyone around the holidays, doing what she could to brighten the waning moments of often lonely lives.”

Carol was also, quite possibly, the reason Mike Royko became Mike Royko.

As David Royko notes in “Royko in Love,” “To read his letters is to watch the die being cast as he applied, for the first time, his wit and facility with the pen to a practical purpose…In the process of wooing the woman he loved, he would also make writing a habitual part of his life. Writing, and my mother, would become the most important parts of his future.”

Here’s a prime example of Mike honing his skills, from September 26, 1954. He was back at Blaine Air Force base from his leave in Chicago, just a few days after asking Carol to marry him:

I’ve been trying to read but all that’s available are recently written fiction novels and they have the same types of plots. Romance. I’m the last person who would be against romance, but baby they all sound so shallow and weak. I’d like to write our story. I wonder if it would sell. It’s got the ingredients. First we take a boy, a very mixed up boy who has a crush on a girl. The girl has already shown indications of someday being a beautiful woman. Then we take the conflicts. The boy feels inferior and never voices his love. Time passes and someone else appears. The boy accepts this because he is young and the young heal very easily and in the young there is hope. Then one day there is no longer any hope and the new wounds hurt and they don’t heal. Then the boy goes to war and he carries with him pictures. Pictures in his bag and pictures in his mind. The pictures in his bag are pretty but the pictures in his mind aren’t. Now we have a boy become a man. A broken heart and war can make great changes. He comes back and he hides. He hides from the thing he loves more than anything else. Then one day there is hope again and the hope becomes promise and the promise becomes love and love like theirs can only have one consummation—they lived happily ever after.

So I could write a wonderful love story—if—I were a writer but since I’m not, the world will have to suffer along its way without knowing about us.

Besides professing his love to Carol in every conceivable way through these months of letters, Mike repeatedly tells her that she is the reason for his ambition to do well in life—to do anything at all in fact.

“If you can partially realize the effect you have and how much more you could have on my life,” Mike wrote on July 8, 1954. “For one thing, if it should ever look like I’m out of the running I could never make Chicago my home. It would be too painful. I’d probably get an officer’s commission and stay in the service….With you I think I could not only set the world on fire—I’d melt it. Most people never realize their full potential because they lack a sufficient incentive. If a person has that motivation, then he’s unlimited. You’d be the incentive. I could do anything.”

He repeats that idea a few times—if Carol had turned him down, he insisted he would not, could not live in Chicago.

Imagine Mike Royko, not in Chicago. Or try, because it is unimaginable.

“I do think there’s something to that,” says David Royko. “Dad would often call Mom when he was working on a column and read it to her, to get some feedback or whatever. The letters we can take at face value. Not every day but the phone would ring and Mom would know this might be Dad calling to read through the column, especially in the Daily News days.”

Yet there were rocky times for Mike and Carol as he ascended to the top of his industry. The column, by all accounts, consumed Royko.

“He was possessed by a demon,” Studs Terkel told Jonathan Eig at Royko’s memorial service at Wrigley Field in 1997, for a fantastic Chicago Magazine account of that day which is unfortunately not available online. “A demon called passion, a passion to set things right,” said Studs. “That demon—without it there would be no Mike Royko. But the demon takes its toll on a human being.”

After the daily column was done, Royko spent too much time after work at the Billy Goat and other favorite haunts, plus softball games. There were arguments at home over his drinking.

“We were out every night,” Terry Shaffer, Royko’s first legman from 1966-1970, told Richard Ciccone. “He never went home, one bar after another, but a lot of other people were going out, too.”

“And Dad was never home,” as David Royko told Ciccone. “It wasn’t the column; it was the bar.”

In 1977, a drunk Mike Royko approached a table of theater folks in a North Side bar and according to one woman, asked to buy her a steak. He was rebuffed and a fight nearly ensued with several men. Whatever started it, Mike apparently ended up breaking a ketchup bottle for potential use as a weapon, getting some ketchup on the woman’s fur coat.

Carol considered leaving Mike at that point, according to Ciccone’s biography. She didn’t. Years earlier, the couple had a made a pact— “Together, forever” — as Royko’s sister Dorothy told Ciccone. Royko had the phrase inscribed on Carol’s coffin.

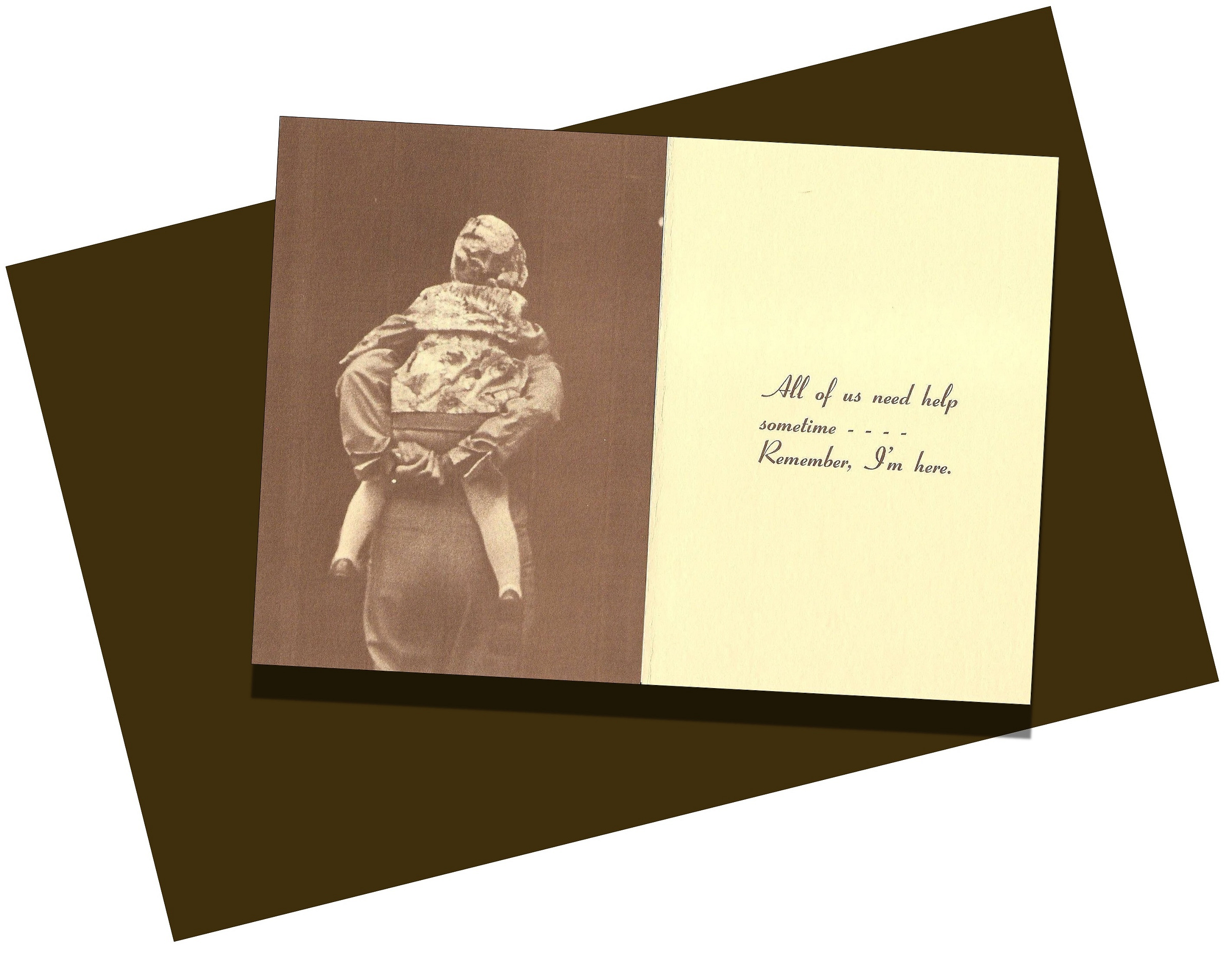

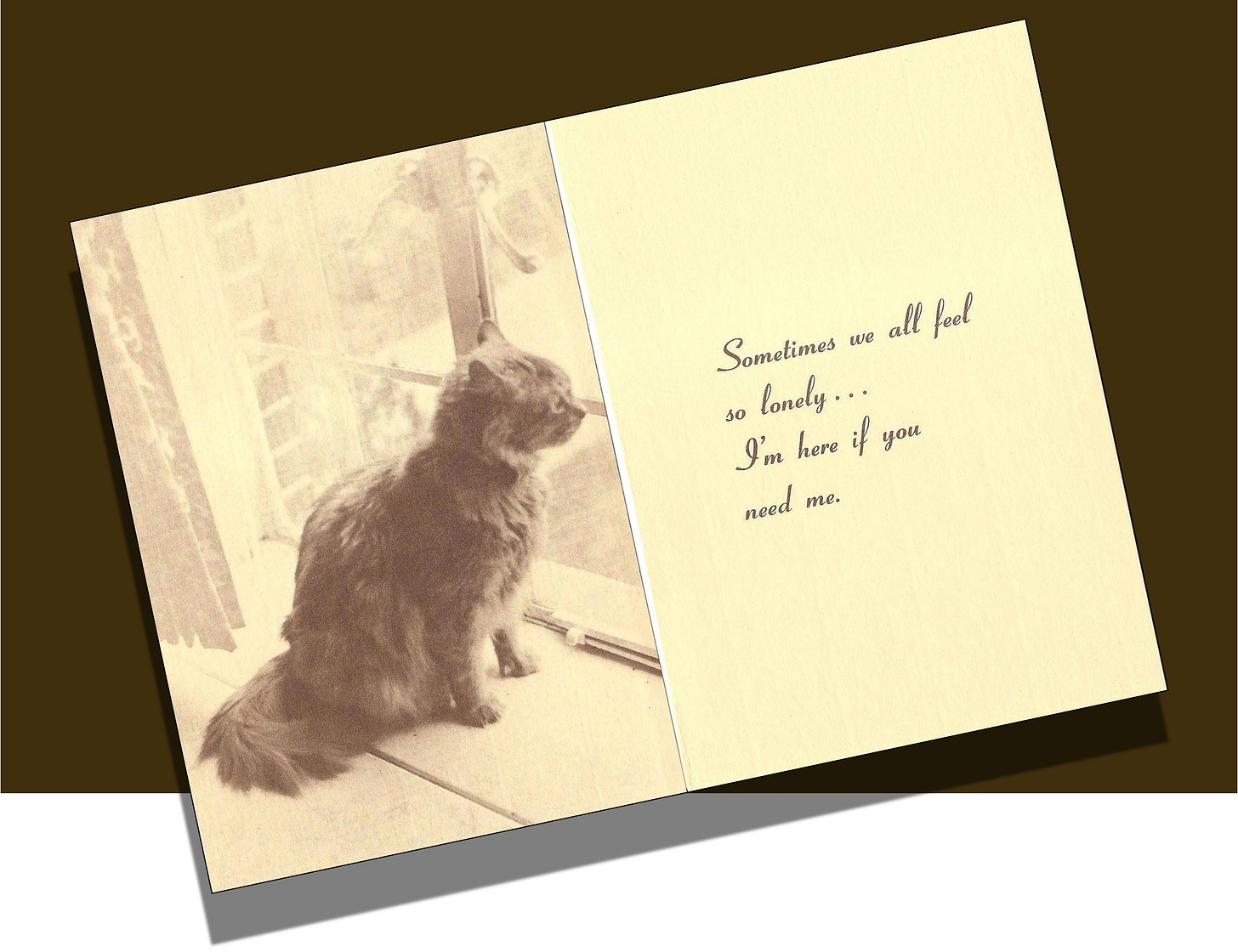

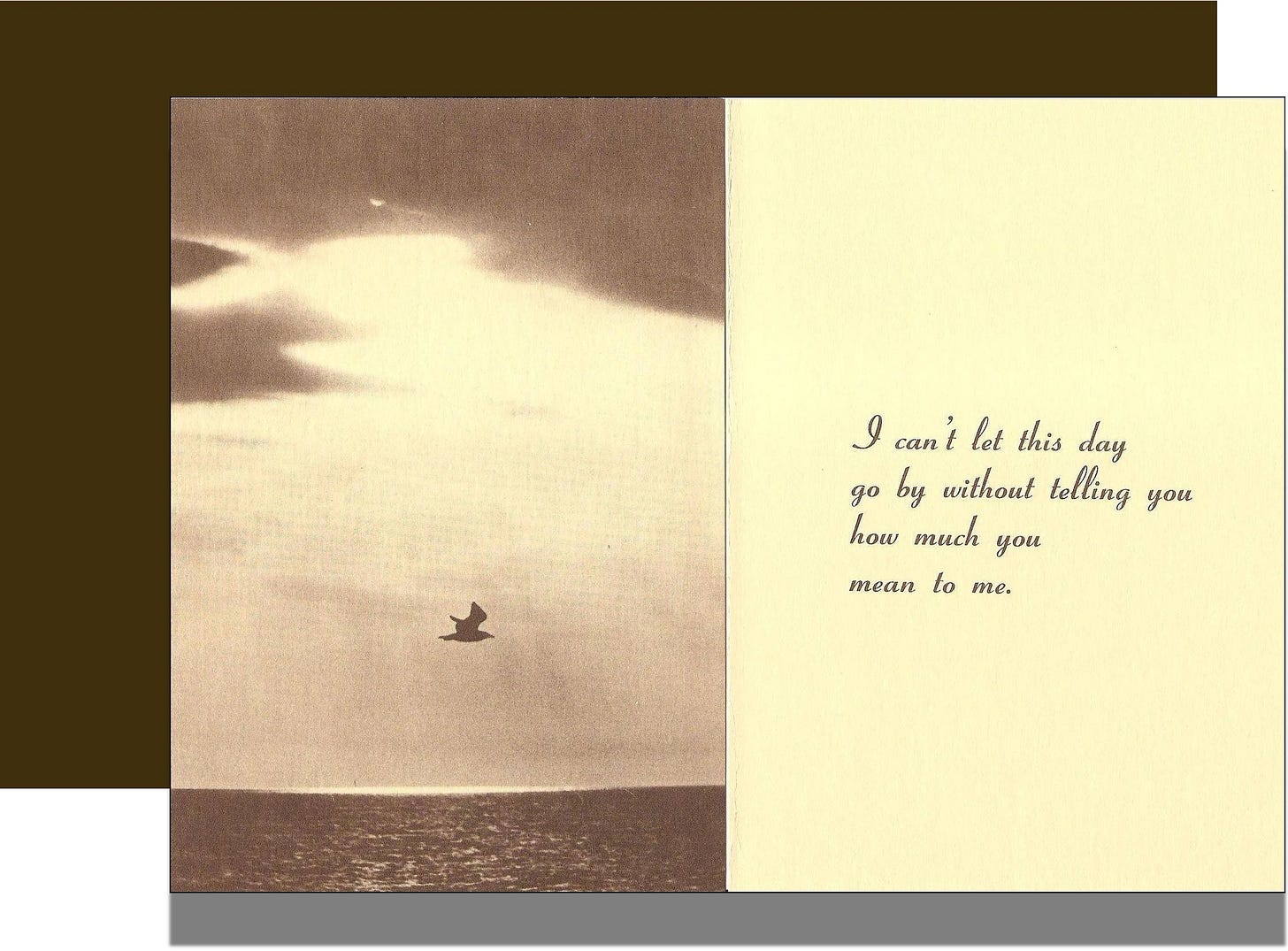

In the later ‘70s, Carol and her friend Sue Crawford started a greeting card business called “I Care.” Focusing on sympathy and bereavement, they worked out of the house on Sioux. Carol provided the art, while both women wrote and edited. They tested card prototypes on terminal patients, finding out what images and messages were most appreciated.

Younger Readers, nothing like these cards existed at the time. “The patients would show us cards that they had received,” Sue said for “The New Entrepreneurs: Women Working from Home,” a 1980 book by Terri T. Tepper and Nona Dawe Tepper that featured the “I Care” collection. “One card said, ‘Get up off of your ass.’ These were sent to people who were terribly ill, and the messages hurt them. Through the testing we found that words that we liked often turned the patient off. Things that we thought were beautiful made them angry, because certain words and thoughts like ‘I need you’ meant demands to them.”

“My mother has had multiple sclerosis for 15 years and is paralyzed from the waist down,” Carol told the Teppers. “She’s got a cancerous tumor on the kidney that she’s refused surgery for. Mother’s Day came, and we had cards for Dad to send to her, for us to give to her, for her grandchildren to give to her. My mother has been watching us as we developed our cards, and she had tears in her eyes because the cards were so beautiful.”

The “I Care” cards were also featured in a 1979 Sun-Times feature on women starting their own businesses from home, written by Vera Chatz.

“Deeply affected by seeing a number of friends and relatives suffering from incurable diseases or dying suddenly in accidents, Carol Royko and Sue Crawford sensed people’s inability to utter meaningful words at tragic times,” wrote Chatz.

Carol and Sue spent two years toting the cards to prospective sellers like hospital gift shops, wrote Chatz. Eventually, they found a distributor and watched the business grow to about 6,000 cards per month at stores including Marshall Field’s.

“The phrase I hate most is, ‘It’ll keep you busy,’” Carol told Chatz. “With a husband, two teen-aged sons, three dogs, and three cats, I hardly need to find something to keep me busy!”

“We know we’re going to be successful,” said Carol, then 44.

But seven months later, Carol suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. She was taken off life support on Mike’s 47th birthday, September 19.

“And that was it for birthdays,” David Royko wrote in a blogpost. “I might’ve tried a quiet, mumbled ‘happy birthday’ one year, but the reaction, the grunt and turning-away, taught me not to try it again. So year after year, I’d try to find some excuse to stop by, either his home or down at the paper, and casually drop something off, like a book or CD, and never with any mention of why. He’d accept it with a quick ‘Oh, thanks,’ and move on to something else. Dad probably would’ve preferred I’d not even done that, but the gift and lack-of-acknowledgment was my way of letting him know I hadn’t forgotten what day it was, on both counts.”

“She was the glue,” David Royko says today.

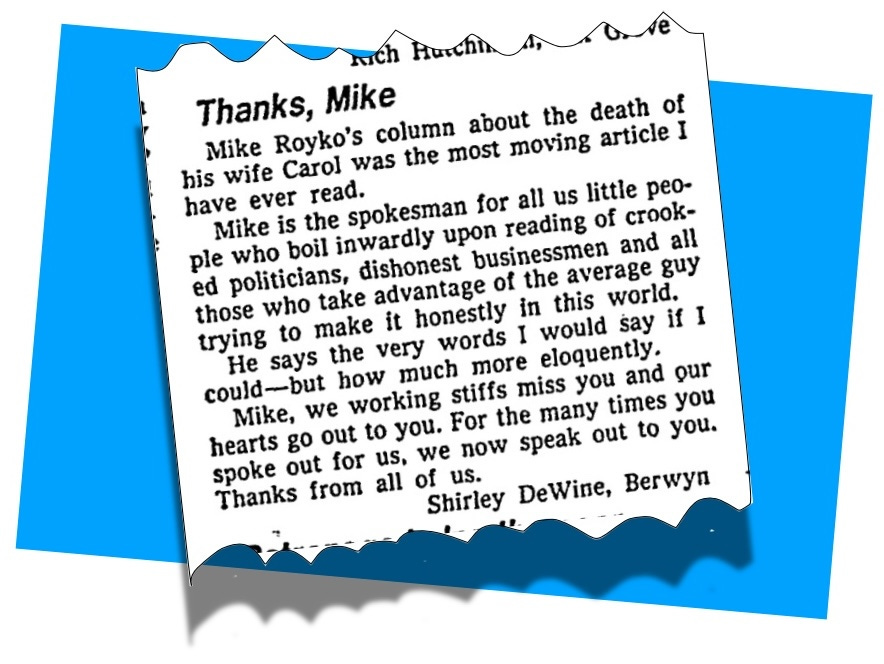

Mike stopped writing the column. He wrote a short thank you to readers about two weeks later.

“Many of you have written to me, offering words of comfort, saying you want to help share the grief in the loss of my wife, Carol.

“I can’t even try to tell you how moved I’ve been, and I wish I could take your hands and thank each of you personally.”

Beautiful as Carol was, Mike wrote, “I took more pride in her inner beauty. If there was a shy person at a gathering, that’s whom she’d be talking to, and soon that person would be bubbling. If people felt clumsy, homely and not worth much, she made them feel good about themselves. If someone was old and felt alone, she made them feel loved and needed. None of it was a put on. That was the way she was.”

“Simply put, she was the best person I ever knew,” Mike wrote toward the end. “Anyway, I’ll be back. And soon, I hope, because I miss you too, my friends. In the meantime, do her and me a favor. If there’s someone you love but haven’t said so in a while, say it now. Always, always, say it now.”

Readers responded. Here’s a touching letter from Shirley DeWine of Berwyn:

Mike returned to the column at the end of October. He waited until November 22 to write about Carol, without naming her or himself, in what is his single most touching column. As David Royko points out in “Royko in Love,” the timing meant that Mike wrote the column on November 21, which would have been Carol’s 45th birthday.

The column recounts how a working couple miraculously bought their own lake house in Wisconsin, after the husband “got lucky in his work” and “made more money than he had ever dreamed they’d have.”

“The best part of their day was dusk,” wrote Mike. “They had a west view and she loved sunsets. Whatever they were doing, they’d always stop to sit on the pier or deck and silently watch the sun go down, changing the color of the lake from blue to purple to silver and black. One evening he made up a small poem:

The sun rolls down like a golden tear Another day, Another day gone."

The column ends with the man going to the house to close it down for the winter, alone.

“He didn’t work quickly enough. He was still there at sunset. It was a great burst of orange, the kind of sunset she loved best. He tried, but he couldn’t watch it alone. Not through tears. So he turned his back on it, went inside, drew the draperies, locked the door and drove away without looking back.”

David Royko points to this column as the best example of a side to Mike Royko that many could forget, overshadowed by “the hard ass side of him, the guy who goes up against the establishment—the tough guy.”

But that side, says David, “was always there. And if it weren’t there, he wouldn’t give a shit enough to write about the underdogs he always wrote about. It didn’t show most of the time but it was reflected in what interested him.”

Mike’s sister Eleanor and her husband, Eddie, moved in to the house on Sioux to hold the family together.

“In fact, she and Eddie sold the house where they lived to move in and take care of the house, take care of our lives, fill in for Mom,” says David. “Dad is the one who needed it. He was an absolute wreck.”

“There was socializing but there was also caretaking,” friend and former legman Hanke Gratteau told Ciccone about this time period for Royko’s friends. “It got to the point where we almost had a schedule of who would be with him at night. None of us could take it every night.”

In time, Royko began dating Chicago reporter Pamela Warrick. “I was deeply in love, and I thought he was, too,” she told Ciccone. “But he was still torn. He still wore Carol’s wedding ring on a chain around his neck. He had pictures of her all over the house. They were on the inside of the kitchen cabinets.”

Now it’s 1981. Mike Royko’s sons, David and Robbie, are both out of high school. He decides to leave the house on Sioux, the dream house that must have contained some very painful memories. Remembering the times he failed Carol must have been hard; remembering the good times, perhaps even harder.

Under the circumstances, why would Mike go to another neighborhood within staggering distance of Milwaukee Avenue?

It only made sense for Mike Royko to get as far away as he could from the places where he had always lived with Carol, or loved her from afar.

So he moved to a condo on Lake Shore Drive.

Life on Lake Shore Drive

The move happened while David Royko was in Europe for the summer of 1981, after graduating from college. David left the house on Sioux, then came back to the condo at 3300 N. Lake Shore Drive to stay while attending graduate school at the Illinois School for Professional Psychology. He’d go on to a career as a clinical psychologist.

“I lived in two houses all my life, the one in Jefferson Park and the one on Sioux, but it was a good age for that to be happening,” David remembers. “It was Belmont and the lake and my grad school was downtown so I hopped on the express bus downtown. It was a fun area to live in.”

David, Rob, and their cousin Debbie all moved into the big condo with Mike. “Robbie’s life has always been wild as fuck, so it was wild there,” says David. “It’s not like there were any rules. We all had our separate lives….We really didn’t overlap much, we each had our own lives, very busy lives.”

No wonder David didn’t see much of Mike. By all accounts in both biographies, the late nights with a rotating group of friends continued, generally starting at Riccardo’s or the Goat, moving on to other bars like O’Rourke’s and ending with jazz pianist Buddy Charles playing until 4 a.m. at the Acorn on Oak.

Mike started dating Pam Warrick in 1980, but she spent the 1980-81 academic year on a fellowship at Stanford, and moved to Washington in 1982 according to Ciccone.

Yes, it’s ironic that Mike spent most nights out drinking with friends before Carol’s death, and then continued the same schedule as a response to her death. But there are many ways to go out drinking with friends, and clearly the nature of Royko’s all-night outings had existentially changed.

So Mike’s July 22, 1981 column, “Talking 4 a.m. blues,” written about a month before he moved into 3300 N. Lake Shore Drive at age 49, reads like a direct transcript of his own thoughts—though it’s based on a phone call from a 53-year-old reader living alone after his wife left him. The reader’s grown kids were off busy with their own lives.

After a short intro explaining the origin of the call—Mike says he “ran off at the mouth on a TV show…about an alderman’s proposals to kill all 4 a.m. licenses for bars in Chicago”—the entire column is ostensibly a direct quote from Mike’s lonely reader.

The reader lives by himself in a small apartment.

“I’ll tell you what my life is. I get up in the morning, go to my business, and spend the day doing the paper work and routine…I could probably do it in five or six hours a day. But I spend 10 or 12 hours a day down there, just to have something to do.”

Most nights the lonely reader goes home, eats, watches TV, sleeps, then starts the routine all over again. But sometimes he can’t sleep. It’s too late to call anyone.

“I start thinking about the past, the way things used to be for me. When you’re my age, you have a lot more past than you have future.”

So he goes to a late night bar. “You know what kind of people I meet in them? I meet lonely people, just like myself. And that’s what you didn’t say when you made jokes about the 4 o’clock joints. You didn’t say that they are place where lonely people can go, the kinds of people who sometimes can’t get through the night all by themselves.

“They want to be around other human beings. They want to have somebody to talk to. And I’ll tell you this, nobody understands the lonely person as much as another lonely person.”

He finishes:

“You ask me, why don’t I find some other interests. I don’t have any other interests. I’ve got my work and I used to have my wife and kids. That used to be enough for me. Now I have my work and that’s all. And that’s not enough, but I don’t know anything else but work and a wife and kids. I could have done without the kids. I knew they’d be gone someday, but I didn’t know I was not going to have the wife.

“So don’t think that 4 o’clock joints are a joke, or that the people in them are jokes. We’re not jokes. There’s nothing funny about us. You ought to drop in some night. You’ll see.”

Mike throws in a final line of his own, a little jab at the City Council, but this is his real closer: “I have dropped in some nights. He’s right. People there aren’t jokes.”

A week later, Mike wrote an open letter to Princess Diana and Prince Charles, which ran on the front page with their wedding coverage on July 30. Let’s all try to forget what a nightmare Diana was walking into as we read Mike’s thoughts for the royal couple.

“It’s really not important that you, Charles, are a prince and king-to-be,” wrote Mike. “And that you, Diana, are a queen-to-be. What I see is something far more important.

“You are a couple of people who just got married.

“That gives you something in common with all the young lovers, and older lovers, of a world that sometimes seems loveless.”

Charles and Diana were no different, wrote Mike, than a “the kid from the Southwest Side of Chicago who is assistant manager of a pizza joint and his bride from Oak Lawn who is going to nursing school.”

“I’m not sure what [love] is myself,” Mike counseled the young couple, “except that it leaves you breathless, makes everything else seem unimportant, and can cause you ecstasy, misery and drive you crazy. And also drive you happy.

“I hope, despite your cool, English manners, that this is what you feel. I hope both of you are crazy and happy.”

Mike cautioned Charles and Diana: “It’s not going to be all kissy-face and patty-fingers and nibbling of earlobes.” They’d get mad at each other, he wrote. They’d get old. (Again, let’s forget what really happened.)

“But if you haven’t become fools, she will say to you that you are even more handsome now than you were before; and you’ll tell her that she’s more beautiful and desirable than she was then. And you’ll mean it. And if you mean it, then it will be true.”

Of course Mike had to finish flip:

“So, kids, good luck and don’t blow it.

“And remember: Squeeze the toothpaste tube from the bottom.”

David’s principle memory of those condo years was the time Mike got robbed in the building’s lobby as he came home late one night in 1984.

“It was a horrible traumatic experience,” says David. “I’m sure Dad was three sheets to the wind at that time. I remember waking up and Dad was like, ‘Goddamit!’ He was screaming and I got up and he was like, ‘I got ROBBED, goddamit!’ I wasn’t even sure what had happened, but he wasn’t hurt, so ‘Whatever I’m going back to bed, with Dad who the fuck knows what was going on.’ His life was pretty wild at that point too. That’s a memory that was indelibly stamped.”

Getting robbed, a friend tells Mike in the column, is “sort of like a tax we pay for living in the city. A victim tax.”

“If so, I’m a solid taxpayer,” Mike noted, since he’d now been through two robberies, one almost-robbery, three burglaries and three car thefts. He was tired of it. It wasn’t the money.

“But I don’t like looking down the barrel of a gun. Especially when the guy holding it is nervously hopping from one foot to another, twitching, breathing hard, and I’m wondering if the stupid bastard is going to blow me away.”

After it was all over, Mike wrote, he was depressed because he hadn’t lived up to his father’s example.

“It happened to the old man many years ago,” Mike explained. “He was a milkman. One morning, before dawn, a guy with a knife started to climb into his truck. The old man kicked him in the face. The guy got up and ran. The old man slammed his truck into gear, drove on the sidewalk, floored the gas pedal, and—bump, bump—the world had one less stick-up man.

“I could have done the same. My car was at the curb, only a few feet away….But it didn’t even cross my mind. In my father’s day, people fought back with ferocity. In my day, we pay the victim tax and wonder what sociological forces brought the poor lad to a life of crime.

“All things considered, running them over is a much better idea.

“Of course, his mother would probably sue me. And collect. So I guess I got off cheap.”

Mike’s wild high-rise years were almost over that night he got robbed in the lobby in 1984. He’d started dating the pretty blond assistant manager of the Sun-Times’ public service bureau, Judy Arndt, in 1982.

Judy, a Rock Island native and competitive tennis player, started her career in Washington working in legislative offices, then doing research for Common Cause. She moved to Chicago in 1972, first teaching tennis at the Lake Shore Club until the roof collapsed in the 1979 blizzard.

Mike and Judy started off their first date at Un Grand Cafe at the Belden-Stratford—now morphed into Mon Ami Gabi—and finished at the Acorn on Oak with Buddy Charles, of course.

Judy was driving—probably for the best, even Royko lovers will admit—and remembers dropping Mike off at 3300 N. Lake Shore Drive:

“He got out, walked toward his door, and then turned around and with that silly grin, jumped in the air, and clicked his heels,” Judy told Ciccone.

Three years later, Judy and Mike were married.

“We got married in ‘85 standing in that room off the living room, there’s the little section that protrudes out--with Seymour Simon reading the vows,” Judy told me recently. “We had a little champaign party beforehand. That was Mike. Mike planned the whole thing. We just wanted a nice quiet ceremony. And lots of champagne. We then went to his club for the dinner (Ridgemoor Country Club) because it would hold more people.”

“He didn’t change at all, not at all,” says Judy. “The living on Lake Shore Drive—I knew Mike so well and he was the most normal guy you could ever want to meet.”

Soon, the Lake Shore Drive days were over. Mike and Judy planned to start a family. They quickly moved, first to Sauganash and finally to Winnetka, where Mike could play with young Sam and Kate in the backyard in between working on the column from his home office.

But we’re not quite done here. As we mentioned at the start, there’s still one more monumental Royko High-Rise Man column left to cover. When Walter Jacobson responded to some gratuitous jabs in Mike’s November 1, 1981 High-Rise Man column, Mike just had to have the last word.

Next and last, we’ll examine that front page High-Rise Man column, which doubles as a 1980s Chicago time capsule—and essentially ended the High-Rise Man concept.

Don’t miss the news from 1972, week by week! Start with the first post here.

Don’t miss the final chapters of High-Rise Man!

Part Six: Walter Strikes Back Walter responds to Mike’s November 5, 1981 column, instigating a monumental front-page Royko High-Rise Man column that doubles as a 1980s Chicago time capsule—and essentially ended the High-Rise Man concept. Here, we prepare for that moment of truth by examining how the paths of Mike and Walter crossed and re-crossed through the middle decades of the 20th century—and then observe their biggest collision.

Part Seven: The Last High-Rise Man [COMING] Because there’s so much fascinating material to cover in Part Six leading up to Mike’s November 22, 1981 column answering Walter Jacobson, that 1980s time capsule of a column gets its own post here.

High-Rise Man Addendum: Bill Granger Weighs In [COMING] A few months after Mike and Walter’s dust-up, Tribune columnist Bill Granger revisited the issue in his own indelible way. To Granger, the question is: Does your past world disappear? You know what Faulkner said. Granger covers this age-old debate from a Chicago perspective.

Can’t get enough Royko? Delve into the whole section. That’s where we go through Mike’s 1972 columns week-by-week, giving political, historical and pop culture background so younger and future readers can fully appreciate all the references and jokes. START HERE.

By the way, this feature is no substitute for reading Mike’s full columns. He’s best appreciated in the clear, concise, unbroken original version. Our purpose here is to give you some good quotes from the original columns, plus the historic and pop culture context that Mike’s original readers brought to his work. Sometimes you can’t get the inside jokes if you don’t know the references. Plus, many iconic columns didn’t make it into the collections, so unless you dive into microfilm, there’s riveting work covered here you will never read elsewhere.

If you don’t own any of Mike’s books, maybe start with “One More Time,” a selection covering Mike’s entire career which includes a foreword by Studs Terkel and commentaries by Lois Wille.

Mary Tyler Moore!