Chapter 2 Notes, Part 3: "Get Smart" to Vince Lombardi, Papa Bear & Pepto-Bismol

Not your father's footnotes. Fun.

HOW DO NOTES WORK? Each book chapter comes with fun Notes on key topics that pop up as our story progresses. Lots of pictures! Chapter 2 begins by following the sun’s rays poking west down the Chicago River at dawn—crossing the Du Sable/Michigan Avenue Bridge and passing over the Wrigley Building, Trump Tower, the IBM Building, and Marina City. So Chapter 2 Notes Part 1 and 2 covered those buildings in order, aided by a three-part Optional History Chapter on the Wrigley Building. Catch up on those anytime you’d like in the Archives. The Wrigley Building Part 3: When Chicago Wasn’t Chicago will also take you through Chicago’s start as a city when Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable and his wife Kittihawa (Catherine) built the first permanent structure on the north bank of the Chicago River.

Now we move past the buildings and the history behind them. What comes next in the story? IBM Building security guard Michael O’Hare, so that’s where we pick up.

HOW DID THEY END UP IN CHICAGO: Michael 'O’Hare and the First and Second Great Migrations

We first met Michael O’Hare sitting in a perfect and perfectly relaxed lotus position on the granite countertop fronting his security desk in the IBM Building lobby. As mentioned there:

His grandma came north to Chicago after the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, part of the First Great Migration of African-Americans from the Jim Crow South, all searching for jobs and a better life for their children. His grandpa’s family joined the First Great Migration before World War I, carrying the same dream to Philadelphia, carefully sheltering that dream from brutal Northern reality the way an old-time traveler might cover a candle’s flame with a vigilant hand on a blustery night. Michael’s grandpa served in World War II and then moved on to Chicago, along with a new wave of African-Africans coming from the South in the Second Great Migration.

African-Americans fled the 20th century South in droves. Barely out of slavery at the start, six million souls made the journey north between 1910 and 1970 according to the U.S. Census Bureau. They fled grinding poverty; Jim Crow laws that kept them from voting and working; and lynchings publicly understood as organized racial terrorism by the mainstream press even at that time.

African-Americans met discrimination and violence in the North too, of course. In Chicago that would mean, among other things, the 1919 race riot in which 23 blacks and 15 whites died. Even so, opportunity in the North was greater—and it called out loud and clear.

The First Great Migration of African-Americans out of the South is dated variously as starting in 1910, 1915, or 1916, and going through 1940, with a lull during the 1930s Depression years. Southern Blacks headed for jobs in the North that opened up after a drastic drop in European immigration due to World War I, and then new federal laws that throttled the number of immigrants allowed from southern and eastern European countries. The Chicago Defender, which became the most important African-American newspaper of the time, propelled the movement by publicizing Southern atrocities and promoting Northern opportunities.

The influx picked up again in the Second Migration as World War II production and jobs ramped up in the 1940s, increasing yet again during the postwar economic expansion. Black Chicago’s population increase was greatest by percentage during the early years of the First Migration, because the city’s Black community was almost nonexistent until the 1890s. But the bigger increase in absolute numbers came during the post-World War II years of the Second Migration.

Chicago’s Black population was 44,103 in 1910, growing to 109,458 by 1920; 233,903 in 1930; and 277,731 in 1940. The Second Migration brought a jump to 492,265 in 1950, and 812,637 in 1960. Blacks went from 2% of the city’s population in 1910 to almost 23% in 1960. The Second Migration trailed off then, as industry and jobs began shutting down and leaving midwest and northern cities like Chicago, which would come to be called “the Rust Belt.”

For decades, Chicago’s burgeoning Black community would be confined by racism almost entirely to “the Black Belt,” an area about a quarter-mile wide between Cottage Grove and Wentworth, stretching initially from 22nd street to 31st, expanding south to 55th Street by 1920, and to 63rd by 1930.

In 1920, 85% of the city’s Black population lived in the Black Belt, with the rest in a West Side colony and some scattered small enclaves around the rest of the South Side, such as Lilydale around 91st and State. After 1940, the Black population broke free of the previous Black Belt borders and began moving in larger numbers to neighborhoods like Oakland, Kenwood, Hyde Park, Woodlawn, Park Manor, and Englewood on the South Side, and Lawndale on the West Side.

The Black Belt was an overcrowded, deteriorating slum area, but also a thriving, vibrant community that came to be known as Bronzeville in the 1930s, a name coined by Black journalist James J. Gentry and promoted by the Defender with a “Mayor of Bronzeville” contest. Bronzeville nurtured Chicago’s Black Renaissance from about 1930 through the 1950s, when the area buzzed with jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong and writers like Richard Wright and Gwendolyn Brooks.

The photograph above is the most famous from Bronzeville in its heyday, taken by photographer Russell Lee in 1941 for the New Deal Farm Security Administration. These young boys posed for Lee across the street from the Regal Theater on 47th and Grand Boulevard, now Martin Luther King Drive. It was part of a project documenting the massive migration of rural poor Americans of all backgrounds to cities during the Depression. WTTW’s “Ask Geoffrey” investigated the photograph in 2015. They identified the oldest boy in the center, so dapper in a double-breasted suit, as Spencer Lee Readus, Jr. Read about it here. Briefly, Readus served in the U.S. Army for World War II, afterward becoming a plaster foreman back home in Chicago, and raised his family in Roseland.

Michael O’Hare’s grandma’s family lived in various apartments in Bronzeville, and his grandma stayed in the area after marrying his grandpa. His grandparents raised their family mainly in a six-flat at 604 E. Oakwood Boulevard, across the street from their parish, Holy Angels Catholic Church. Unfortunately, the building is gone—though it was good to see that the rest of the block is intact and well-tended today. Even the vacant lot is well-kept.

Below is the Holy Angels Catholic Church Michael’s grandparents first knew, a Greco-Romanesque building erected in 1896-7, designed by James J. Egan. This was the parish’s third church. Irish congregants began the parish in 1880, meeting in a room in “Grossman’s Hall” on nearby Cottage Grove. Anti-Irish and anti-Catholic prejudice was keen at that time. The Irish parishioners had to buy land in secret to build a Catholic church. The photograph is a 1912 postcard, thanks to John Chuckman’s Photos On Wordpress.

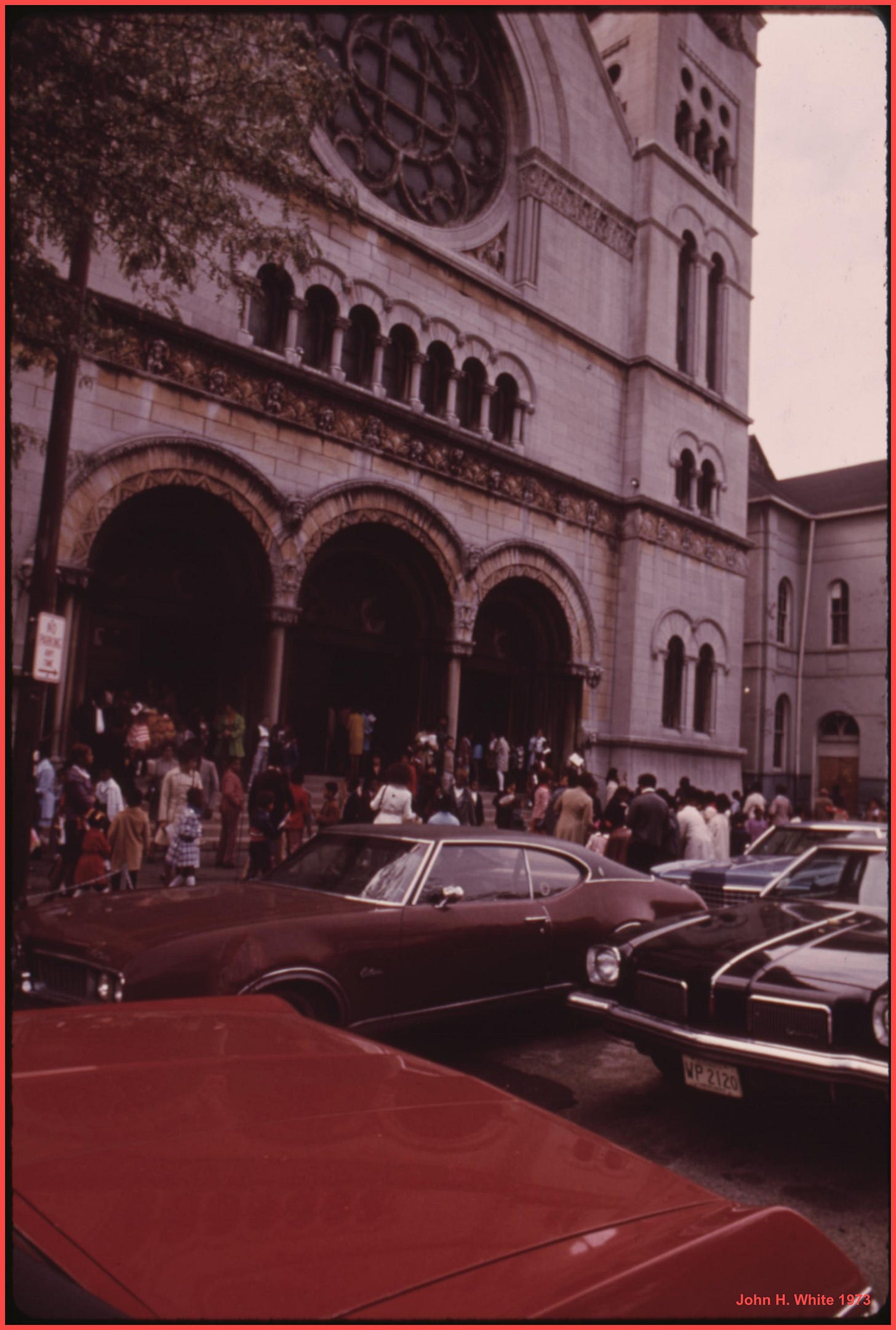

And here’s Holy Angels in a wonderful candid 1973 shot by John H. White. At this time, Holy Angels was the largest Black Catholic parish in the country, according to pastor Fr. George Clements. Sadly, the church burned down in 1986 when an electrical fire began in the basement overnight.

This is the new Holy Angels Church, built on the site of the old church. The parish was rechristened in 2021 as Our Lady of Africa Parish. The Archdiocese of Chicago has been closing and consolidating parishes for years now as the city’s Catholic population declines. Our Lady of Africa Parish merges five area churches—Holy Angels, St. Ambrose, St. Anselm of Canterbury, Corpus Christi, and St. Elizabeth of Hungary.

Below, the current sign for Our Lady of Africa Parish. Like so many Catholic Churches, Mass is said in many languages, reflecting the origin of the parishioners.

Wabash

The first half of the word is pronounced “Awwwww!” with a “w” in front. The second half is pronounced with a short “a”. Slightly more emphasis should be placed on the “Awww” part. “Wabash” is the English form of the Native American (Miami) name for the Wabash River. According to “Indian Place Names” by Ronald Baker and Marvin Carmony, the word “wabash” refers to a bright white inanimate object, in this case a bed of limestone in the upper Wabash River.

Illinois Central (IC) train station at Randolph (Millennial Park)

Steve takes the IC commuter train to work from his home in Hyde Park, getting on at 53rd Street. The main line runs on an embankment above the South Side neighborhoods it serves, always getting closer to the lake as it approaches downtown. It’s the same train line Steve took to get downtown from his old home in Roseland, when a Roselander would venture that far. Back then, the seats were wicker and destroyed all the women’s nylons. And the 1972 women were all wearing nylons.

As a kid, Steve took the IC downtown with his family to see Marshall Field’s Christmas windows, and he took the IC with his rebellious Nona in 1972 on a secret journey to see “The Godfather.” Steve’s mom said he was too young, but Nona wanted company, and she wasn’t waiting months until the blockbuster film finally moved on from the Chicago Theater and filtered out to smaller neighborhood theaters—for that is how movies worked in 1972.

Back then, the seats were wicker and destroyed all the women’s nylons. And the women were all wearing nylons in 1972. The single-story train cars were nearly 50 years, ancient and delapidated. The IC was slowly adding the first shiny new double-decker orange-and-silver train cars of a fleet ordered from the manufacturer in 1969.

The IC’s main line runs on an embankment above the South Side neighborhoods it serves, always getting closer to the lake as it approaches downtown. Grown-up Steve gets on the IC at 53rd Street. The first good glimpse of the lake comes right here, but you have to look quickly as the train rumbles over the 53rd Street viaduct. After 47th, the buildings lining the track’s east side stop abruptly. Now the train runs just west of Lake Shore Drive all the way to 12th Street, where it reaches the southern end of Grant Park, often called “Chicago’s front yard.”

Here the IC tracks begin rushing through the city’s front yard like a river in a railroad canyon. The railroad canyon is soon one level below grade, with stone walls just like the real thing. Here’s a slightly newer view than the Mighty IC logo above, though this one is also before 1976, since the Art Institute’s 1976 addition isn’t there yet:

North of the Art Institute—after the foreground of this photo ends—the tracks used to pass a giant parking lot to the east, then disappear entirely underground by the time they reached Randolph. Now the tracks disappear sooner, hidden by subterranean parking garages and Millennium Park.

Here’s another postcard from John Chuckman, shot from the east overlooking the old vast parking lot. It’s like an asphalt Great Plains. You can see the Wrigley Building peeking in on the right side in the distance.

Steve gets off the IC at the end of the line, at the main station underground at Randolph and Michigan. It’s nothing special and never was. Steve and his fellow IC commuters herd themselves like intelligent cattle through the Randolph station’s corridors, so reminiscent of Stockyard chutes with the low ceilings and stuffy old air. Finally they swell up the stairs that deposit them next to the broad stone steps of the old library’s front entrance. Then Steve and his fellows all blink in the sudden sun. Their first glimpse of the Loop always radiates from that southwest corner of Randolph and Michigan.

The IC commuter train line is now part of the regional Metra train system, so Steve is really arriving downtown at the Randolph Street Metra station, which isn’t even the Randolph station anymore. It was renamed for Millenium Park after Chicago spent hundreds of millions of dollars to turn the northwest corner of Grant Park into a tourist Disneyland at the turn of the 21st century.

To anyone who grew up taking the IC back in the day, it’s still the IC, and still the Randolph station—or just “Randolph.” People who call this train line “Metra” give away their relative newcomer status. People who call it “the IC” give away their old-timer status. Which status is preferential depends on your perspective. Neither should be preferential, but we all know everybody has a preference.

The Mighty IC: Even a train has to start somewhere

Most people remember, in a general way, that Chicago beat out other Midwestern cities like St. Louis to become the country’s central hub for transportation and, thus, trade. But that didn’t happen automatically just because Chicago sits on the shores of Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Chicago River.

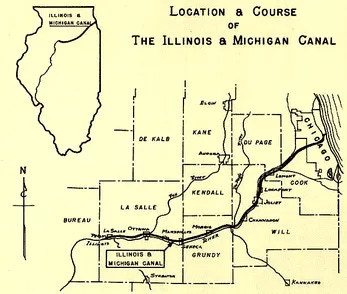

As Donald L. Miller puts it in his epic book City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America, “Nature hadn’t created Chicago….she had merely made it possible. The city would not have been set on its course had not men of energy and empire first envisioned and then cut a canal”—the Illinois and Michigan Canal.

The I&M Canal opened in 1848, linking the south branch of the Chicago River to the Illinois River, running from Bridgeport to LaSalle-Peru. This 96-mile long, 60-foot wide artificial river, dug by Irish immigrants over the course of a dozen backbreaking years, connected Chicago by water for the first time with the Mississippi.

Suddenly, ships could travel from New York to the Gulf of Mexico—via the Erie Canal to the Great Lakes, on to Chicago, then through the I&M Canal to the Illinois River and finally the Mississippi.

That was Chicago’s first punch, a hefty left jab at all its Midwest rivals. The knock-out came chugging along railroad tracks.

“It was water, ironically, that guaranteed Chicago’s place as the nation’s railroad hub,” Miller explains. “With the completion of the Erie Canal and the Illinois and Michigan Canal, Chicago’s location as the terminus of an all-water route between New York and the Gulf of Mexico, the longest inland waterway in the world, made it virtually certain the city would become a major rail center.”

And it happened fast.

“By 1857, Chicago was the center of the largest railroad network in the world, consisting of three thousand miles of track,” writes Miller. “Almost a hundred trains entered and left the city every day, and everywhere its trains went, they changed frontier into hinterland and brought to the city the multiplying products of farms and forests.”

Chicago’s first railroad was the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad, starting operation in 1848. But, writes Miller, “The railroad that had the earliest and longest-lasting effect on Chicago’s physical environment was the formidable Illinois Central.”

Even back then, Chicago became Chicago through clout. In 1846, Illinois’ newly-minted U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas went to Washington determined to pass the necessary federal legislation for an Illinois Central Railroad, running the full length of the state and down to the Gulf of Mexico. Douglas succeeded—and after moving to Chicago in 1847, he amended the IC plan to include a branch to his new hometown. Then Douglas bought a lot of the land that now makes up the near South Side, which an IC Chicago branch would need. Douglas simultaneously made a nice profit selling the railroad the land it needed, and made his remaining holdings more valuable as part of the IC route.

You can still see Stephen Douglas from the IC as it passes 35th Street, on the west side of the tracks. Sort of. You’re looking at a ten-foot high statue of Douglas, dwarfed by its 40-foot marble column. This seems almost a purposeful irony, since the diminutive Douglas was known, of course, as “the little giant.”

The statue tops Douglas’s tomb, no longer set in quite so large and elaborate a park as in the postcard above. Douglas is a controversial historical figure, since he argued against Abraham Lincoln’s anti-slavery position in their famous 1858 debates, when Lincoln unsuccessfully challenged Douglas’s senate seat. If you haven’t read about Douglas since grade school, though, the details are fascinating, including Douglas’s final travels to rebellious states, attempting to stave off secession. Douglas’s death from typhoid in 1861 at 48 was at least partially attributable to those travels, which left him in sight of the IC.

“In 1856 the 705-mile-long railroad from Chicago to Cairo, the longest in the world, began regular service, and Chicago immediately felt its impact,” writes Miller. “Trade on the upper Mississippi that had previously gone downriver to St. Louis was rerouted by rail to Chicago, whose boosters began calling the Illinois Central ‘the St. Louis cutoff.’”

As we know, the mighty Illinois Central’s wide, raging river of railroad tracks still gouges a canyon through Grant Park, Chicago’s front yard.

But Senator Douglas didn’t own Grant Park, so how exactly did that part happen?

Back to Donald L. Miller, and the I&M Canal. In 1836, the city’s lakefront strip of shoreline—stretching south from the site of the old Fort Dearborn on the south bank of the Chicago River—was part of the canal land carved up into lots and sold by the state of Illinois. The state acted through canal commissioners whose last names will be familiar to Chicagoans still in 2022: William F. Thornton, William B. Archer, and Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard. These three men, all on their own, decided not to sell the lakeshore. Instead, they drew up the first famous map labeling Chicago’s lakefront “Public Ground—A Common to Remain Forever Open, Clear, and Free of Any Buildings, or Other Obstruction Whatever.”

Fast forward two decades. Wealthy Chicagoans of the 1850s lived in fine houses lining South Michigan Avenue, overlooking a popular lakefront park. But Lake Michigan had eaten away at the park until storms sometimes drove the waves right across Michigan Avenue against Chicago society’s front steps. Nobody wanted to pay for building a seawall or other barriers to contain the lake. So in 1852, the city council “cut a deal with the Illinois Central, giving it a lakefront right-of-way to the terminal and freight complex it had just purchased on the old Fort Dearborn estate in exchange for construction of the badly needed dikes and breakwaters,” writes Miller.

The early IC ran into Chicago on that strip of lakefront land saved by Thornton, Archer and Hubbard, though it was now underwater. So the tracks originally sat on elevated train trestles several hundred feet offshore, with a parallel line of breakwaters protecting the tracks from Lake Michigan and simultaneously saving the inner shoreline. Here is an early map thanks to the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal:

And here is a photograph of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train bound for Chicago over the IC train trestle in 1865—also thanks to the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal. The train looks like it’s literally rolling across the water.

Chicagoans would fight the Illinois Central Railroad for the rest of the 19th century over the southern lakefront in Grant Park. It would take a nearly 20-year legal battle led by Chicago merchant Montgomery Ward to finally settle the question in favor of the public. That, and a lot of landfill through all the decades since, created the Grant Park you see today.

In 1972, the IC is in the process of merging with the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad. By the end of the year, the company will technically be the Illinois Central Gulf Railroad (ICG), but everybody will still call the company and its commuter train “the IC.”

The IC (railroad) will dump—er, sell—the IC (commuter line) to Metra in 1988, the company that runs Chicago’s other commuter trains. Then, as we noted earlier, the IC will become the “Metra Electric,” since it’s the only local commuter line that runs on overhead electrical lines rather than using diesel train engines.

HOW DID THEY END UP IN CHICAGO: Steve Bertolucci and Italians Come to Chicago

Italians left Italy in droves— about 25 million between 1876 to 1970. Of those, five million came to the United States between 1876-1930. Italians fled grinding poverty, in an agricultural society where peasant farm workers earned next to nothing, with no hope of ever owning land.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, America’s older immigrants considered the poor newcomers—mostly Italians, Slavs, and Jews--to be criminals, lunatics, paupers and morons. Italians were the most despised of this group. In the mid-1930s, young Bronx woman Marie Planitz told her father she planned to marry her boyfriend, Vince Lombardi. Her father said, “No you’re not. He’s Italian.” To deal with the wave of these undesirables, Congress passed a series of restrictive laws culminating in the Immigration Act of 1924. Italian immigration alone fell from 222,260 in 1921 to 6,203 in 1925.

In Chicago, the largest concentration of Italians clustered along Taylor Street on the Near West Side, just south of the Loop, not far from Jane Addams’ Hull House. Mayor Richard J. Daley would demolish much of that neighborhood in the 1960s to build the University of Illinois at Chicago, then called “Circle” campus. Circle Campus spread its cement and steel buildings for blocks and blocks, leaving behind a just small slice of Little Italy along Taylor Street.

Other Italians, including Steve’s grandparents, ventured further south of downtown looking for work along the Illinois Central (IC) railroad tracks--to Roseland, Kensington, and Pullman. The mighty Pullman company at first wouldn’t hire Italians, but eventually relaxed that restriction. Roseland became the second largest Italian community in Chicago.

The Far South Side Italian community grew there, centered around St. Anthony of Padua Roman Catholic Church--which is exactly where Steve’s entire life was upended, perhaps ruined forever, in a mysterious morning meeting in 1972.

Below, the “new” St. Anthony of Padua Roman Catholic Church, built in 1964 to replace the smaller old church. The official address is 11550 S. Prairie, but the church actually stands at the northeast corner of Kensington and Indiana. When Steve was a kid, St. Anthony’s featured Italian language masses in addition to English—after the Vatican II changes in Catholic rules allowed vernacular services rather than all Latin all the time. To Steve the English masses sometimes sounded like they were in Italian too because of the priests’ heavy Italian accents. He still likes to imitate them. Now the parish offers daily 7:30 A.M. masses in Spanish, and another Spanish mass on Sundays.

Below, admire St. Anthony’s gorgeous marble alter. C.J. Martello, who writes the “Petals from Roseland” column for the Fra Noi newsletter, wrote that Fr. Adolph Nalin, the long-time St. Anthony pastor who oversaw construction of the new church, traveled to Italy himself to pick out everything:

Father also visited the quarries of Tuscany and the Arighinni Studios in Pietrasanta to see the workers harvesting marble using centuries-old techniques. Those same skills were brought across the ocean by the artists who completed the sculptures that can be seen on the side altars and, of course, in the niche above the front doors where the 13-ton St. Anthony statue appears.

Fr. Adolph Nalin was so into the marble that, if you look at the picture of the marble workers at the Communion rail, you’d swear you can see Fr. Nalin doing his part. I asked the late Angelo Piolatto about this last year and he set me straight. It turns out that Fr. Nalin brought his almost identical-looking brother and his two nephews over from Italy to work on the marble for St. Anthony’s.

Here’s that 13-ton statue of St. Anthony of Padua over the front doors. As C.J. Martello mentions, it was a big day when they used a crane to slowly hoist St. Anthony into position. The kids from St. Anthony’s school were let out to watch, and Steve’s Nonna pushed him over in a stroller, since she was babysitting and lived right around the corner.

Here’s Steve’s Nonna’s building, 233 E. 115th. The front entrance to the upstairs apartments is the center door with the small awning. When Steve was a kid, the corner was a bar that changed a lot, and the other side was a hardware store run by the building’s owner. Nonna dropped in to shoplift almost every day, because she said the rent was too high. The back of the building (right) is really Nonna’s place—the second floor porch door on the extreme left. Nonna’s windows overlooked an unpaved cinder alley, and across that, the brick wall of St. Anthony’s rectory. The new church is just south down Prairie and around the corner on Kensington.

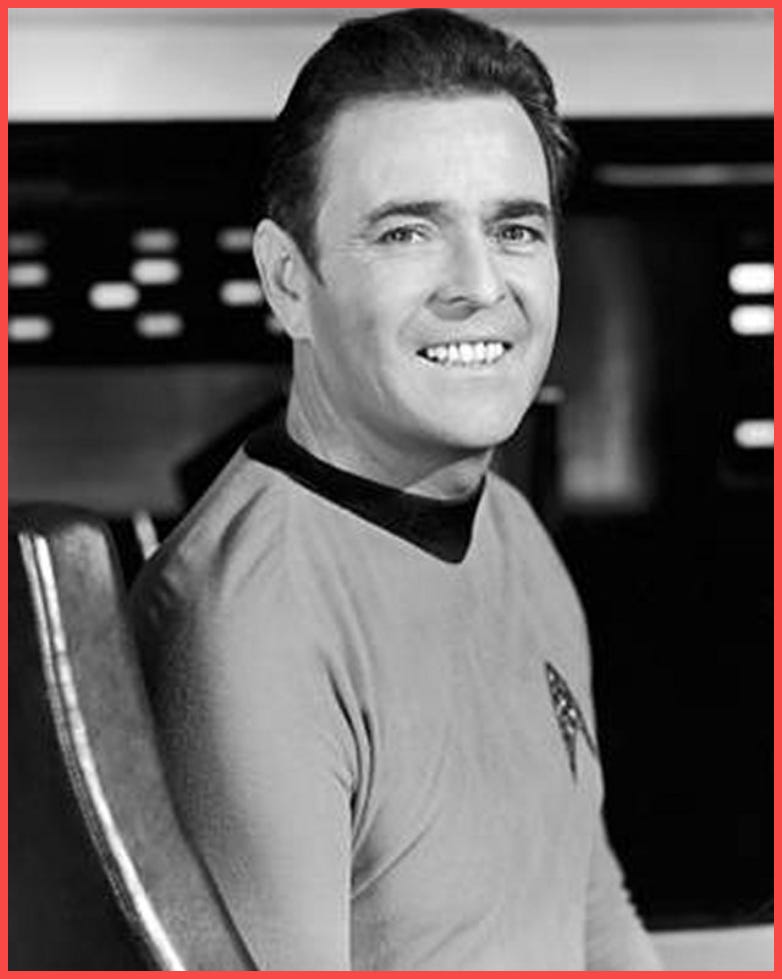

Star Trek

C’mon. You know what Star Trek is. I don’t care when you’re reading this, you know what Star Trek is. I won’t even put a caption on the picture.

Jesus Christ Superstar

JCS was and is a wildly popular 1970 rock opera by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, depicting the final days of Jesus Christ--his capture by Roman soldiers, trial, and crucifixion. It totally rocks. On the original album, the part of Jesus is sung by the unparalleled lead singer of Deep Purple, Ian Gillan, which explains the divine nature of that group’s seminal rock song Smoke on the Water. JCS was released first as a concept album in 1970, then quickly staged the following year on Broadway and filmed as a movie in 1973.

Steve knows the lyrics to Jesus Christ Superstar better than the Happy Birthday song because his mom bought a copy of the expensive double album in 1971 on a trip to Polk Brothers, 85th & Cottage, looking for a washing machine.

Mrs. Bertolucci was gambling that Steve’s dad wouldn’t notice an extra $7.19 tacked onto the price of the washer. He did, though, because $7.19 is $49 in 2021 money—a significant purchase for a family with six kids. JCS was a double album—impressive enough by itself—AND it came with a lyric booklet. Steve had lots of time to listen to JCS and study the lyrics, while sitting around in the basement during tornado warnings every spring and fall.

The song Steve automatically thinks about in 2003 as he gets onto the elevator at the IBM Building with two black eyes is This Jesus Must Die, sung by a group of Jewish high priests and their leader, Caiaphas, who view Jesus as a dangerous rival. The high priests are meeting to decide what to do about Jesus as he enters Jerusalem, greeted by cheering throngs. “Listen to that howling mob of blockheads in the streets,” sings the high priest named Annas. “A trick or two with lepers and the whole town’s on its feet.” All the priests sing the resounding refrain: “He is dannnn-ger-ous!”

I’d Rather Fight Than Switch/Tareyton Cigarettes

Strange but hugely successful ad campaign conceived by New York advertising agency Batteh, Barton, Durstine & Osborn (BBDO) to lure more Americans into killing themselves. Well done, BBDO!

But Steve never did understand why anybody would fight over what kind of cigarette somebody else was smoking. Certainly none of the grown-ups around him seemed inclined to do so. They all had their personal favorite brands, but if they were out of cigarettes themselves, the grown-ups Steve knew would smoke whatever they could get.

Get Smart

“Get Smart” is a half-hour sitcom (1965-1970) created by the legendary Buck Henry (The Graduate) and even more legendary Mel Brooks (The Producers). That’s all you need to know to know you should watch it.* Of course, this presumes Mel Brooks was not canceled after I wrote this, and utterly erased from history, for joking about Hitler.

But what do the elevator doors in the IBM Building have to do with Get Smart? Here goes:

The show follows bumbling secret agent Maxwell Smart from good spy agency CONTROL, which battles evil spy agency KAOS. These are acronyms, but the creators never figured out what the letters stood for.

In the opening credits, Max careens around a city corner in a red convertible, pulls up to an anonymous city building and hurries inside. There’s no sign, but we know this is CONTROL’s secret headquarters. Cut to Smart exiting elevator doors in a basement—but as the doors open, we see Max is actually coming down a flight of stairs.

Now the camera, from behind, watches Max march purposefully down a long hallway, through a series of heavy metal doors. The doors open before Max as he approaches, then slam shut behind him with an echoing bang. Finally, the last set of doors opens to reveal a 1960’s era phone booth. Max opens the phone booth door, closes it behind himself, picks up the payphone receiver, puts in a coin, dials, puts the receiver back down, turns to the camera and folds his arms. A trapdoor apparently opens below Max—and he falls out of view.

For the ending credits, the camera is stationed at the entrance end of the long hallway and watches Max walk back. This time the heavy metal doors are all open, and they don’t close behind Max as he passes. When Max gets to the last door, he turns around and looks expectantly back down the hall. The doors start closing, in sequence. But the last doors still don’t close. Max looks puzzled and walks up to the doors, which promptly slam shut in his face.

Max turns back around to face the camera, both hands up, cupping his nose. This is the part Steve thought of as he entered the crowded elevator in the IBM Building on October 6, 2003, and turned to face the elevator doors. Watch it HERE.

Bonus question: How many doors does Maxwell Smart go through to reach CONTROL headquarters? Answer at the end.

*Watch Get Smart, just don’t pick the episode “99 Loses Control,” from 1968. Bob Hope makes the worst Get Smart celebrity cameo appearance ever as a hotel waiter bringing room service to a male doctor and his female fiancé. Bob Hope tells Get Smart star Don Adams, re the doctor and his fiancé, “Poor girl, when he starts operating, she’ll have as much chance as a draft card at a hippie love-in.” Pure, vintage Hope. There’s no way Buck Henry or Mel Brooks wrote that. Or else they wrote a horrible vintage Bob Hope joke as an ironic gesture. Bob Hope was the biggest comedian of his generation, and that’s the best he could do.

America’s favorite cigarette break/ Benson & Hedges 100s

Always looking for a new way to persuade people to kill themselves, the Einsteins in U.S. tobacco companies came up with the idea of longer cigarettes in the late 1960’s. Philip Morris’s Benson & Hedges 100’s were, as the name suggests, 100 millimeters long--compared to 85 millimeters for the “king-size” cigarettes at that time. The soon-to-be iconic “America’s favorite cigarette break” advertising campaign was created by New York’s Wells, Rich, Greene agency. The elevator door version is, to Steve, the most memorable. You’ve already seen that one above and in Chapter 2, so here’s another one below. Oddly enough, the guy in the red sweater looks an awful lot like Maxwell Smart.

HOW DID THEY END UP IN CHICAGO: Bill Pulaski and Poles Come to Chicago

Poles fled Poland by the millions starting in the mid-1800s. Mass Polish immigration ended here only because Congress passed the 1924 Immigration Act to stop people from the countries it considered undesirable, and Poland was prominent among them. That first wave of Poles constituted an army of impoverished peasants, whose odyssey is commonly called “Za Chłebem” (“For Bread”).

Hey, it’s not a contest, but these Poles were pretty bad off. Like other Eastern European peasants, Poles were serfs until the mid 18th century and sometimes beyond. A serf was a slave to the local aristocrat, with the caveat that a serf was legally tied to a specific plot of land. Serfs came with land like a prize in a Crackerjack box. Polish serfs in Russian-occupied Poland weren’t freed until March 3, 1861--about a month before the start of the U.S. Civil War.

And let’s remember that Poland tends to get invaded by its neighbors and dismembered, sometimes disappearing from the world map entirely. There were so many partitions of the poor country, they’re officially numbered like new Star Wars movies. Here’s a Wikipedia map of Poland’s dismemberments in the 18th century.

Chicago has long billed itself as the largest Polish city outside of Poland. Often we say Chicago is the largest Polish city outside Warsaw, but that’s a bit of local hyperbole.

Indisputably, Poles became the biggest ethnic group in Chicago by 1930. Poles settled here most famously on the Northwest Side, spreading up Milwaukee Avenue or “Polish Broadway.” Chicago novelist Nelson Algren, who won the first National Book Award in 1950 for The Man With The Golden Arm, lived and set his fiction in the old Polish neighborhood along north Milwaukee—though he was Jewish and born on the South Side. Poles also settled southwest along Archer Avenue; and in large enclaves in Back of the Yards, South Chicago and Hegewisch.

Bill’s family settled in Hegewisch, where his grandparents could have lived their entire lives within a few blocks and never learned English. Hegewisch is a small neighborhood on Chicago’s southeast border.

Few know it, but Hegewisch is named for Adolph Hegewisch, president of the long since defunct U.S. Rolling Stock Company, who hoped to create his own planned company town. He was not nearly as successful as George Pullman. Adolph ran out of money. Hegewisch was already part of Hyde Park Township, and joined Chicago when the township was annexed in 1889.

Pretty soon, steel mills and other heavy industry came to the Hegewisch and the neighboring East Side, and everybody forgot Adolph Hegewisch. Bill’s grandpa worked at the nearby Ford plant, upholstering car interiors for nearly 50 years. He had no idea who Adolph Hegewisch was. His grandma worked as a maid in Hyde Park hotels whenever she could. Steve can see one of the hotels where Bill’s grandma worked from his dining room window today—the Del Prado at the southeast corner of 53rd and Hyde Park Boulevard.

Beautiful Polish churches dot Chicago like powdered sugar on a kolacky. Bill’s family attended St. Florian’s, 13145 S. Houston. It’s not one of those big fancy old Polish churches on the Northwest Side. Like Hegewisch and the people of Hegewisch, St. Florian is not fancy—but it works hard and gets the job done.

Paczki Day

The correct name for the day before Ash Wednesday—as far as Bill and many fellow Polish-Americans are concerned.

Ash Wednesday is the first day of Lent, a 40-day period (not counting Sundays) of fasting and prayer leading up to Easter, the day Christians believe Jesus rose from the dead (the Resurrection). Lenten traditions were in place by the fourth century, but fasting rules continued evolving. In medieval times, Catholics abstained from meat and dairy on weekdays during Lent. So before Lent began, everyone was desperate to eat food that would go to waste. The day before Ash Wednesday was their last chance, hence frenzied celebrations became popular in Catholic countries, such as the better known French Mardi Gras.

In Poland, delicious paczki (pączki) became a traditional treat to make and gorge upon before Lent. In Poland, paczki are mainly eaten the Thursday before Ash Wednesday back. Polish-Americans shifted to Tuesday, the day before Ash Wednesday. “Paczki” is plural in Polish, but Polish-Americans use it as a singular word and say “paczkis” for plural. Sorry, Old World.

The paczki is a fabulous round piece of fried dough filled with jelly or pastry cream, topped with powdered sugar or a simple glaze. In other words, a jelly doughnut. If that doesn’t impress you, remember that simplicity must be pretty great, or there wouldn’t be so many famous quotes about it. For instance, the great Polish composer Frederic Chopin: “Simplicity is the final achievement. After one has played a vast quantity of notes and more notes, it is simplicity that emerges as the crowning reward of art.”

If you would like to eat a paczki on Paczki Day, there are several steps to take.

1. Find out when Paczki Day is. That means counting back from Easter. Most people simply check with a church calendar, or if you are Catholic, you check with the Church. That’s because the Catholic Church’s first council, the Council of Nicaea in 325, decreed that Easter would fall on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal (spring) equinox. March 21 was picked as the official equinox date. Depending on the moon, Easter can fall on any Sunday from March 22 to April 25. Various church organizations have tried unsuccessfully to set a permanent date for Easter. But they would have to get the Pope to go along with it, and why would he overrule the Council of Nicaea?

2. Pick the best local Polish bakery you can, call them, and place an order for as many paczkis as you can afford. Ordering in advance will be crucial if the bakery is any good.

3. When you buy the paczkis, if the person behind the bakery counter pronounces the word “punch-key” or “pownch-key,” let it go. Bill wouldn’t let it go, but you should. Bill insists “poonch-key” is the only correct pronunciation, but any language includes a variety of dialects.

To back up Bill’s opinion on pronunciation, consider that the foremost annual Pierogi Fest in the nation is held in Whiting, Indiania. Whiting would border Chicago’s East Side along Lake Michigan if it weren’t for a sliver of Hammond, Indiana getting in the way, so Whiting is also quite close to Hegewisch. Whiting’s Pierogi Fest features both a “Mr. Pierogi” and a “Miss Paczki.” The Whiting Pierogi Fest specifies that Miss Paczki’s name is pronounced “POONCH-key.”

The Whiting Pierogi Fest also specifies that Miss Paczki is “the vivacious pastry with Lady Godiva-like hair and red ruby platform shoes. Charm (and jelly) just ooze from her presence. Our sphere-shaped, deep-fried, dough sweetheart with jelly filling and powdered sugar, she is happiness personified.”

This year’s Pierogi Fest is scheduled for July 29-31, 2022. Check out the website HERE.

Starship Enterprise transporter/Scotty

Don’t start with me. You know who Scotty is and why he’s the most trustworthy person to operate the transporter, next to Spock.

Bears v Green Bay Packers

The Chicago Bears slammed into the Green Bay Packers for the first time on November 27, 1921. Green Bay kicked off. A tough young Chicagoan returned the ball for 20 yards: George Halas, Bears co-owner and coach, legendary “Papa Bear.” Another legend played against Halas that day: Packers co-founder and coach Curly Lambeau, listed as both quarterback and placekicker.

It was the start of the longest, craziest rivalry in American sports. Chicago guard “Tarzan” Taylor punched Green Bay tackle “Cub” Buck and broke his nose that day during the game, so you could say Chicago started it.

Back then it was already big city versus small town—In 1921, 2.7 million Chicagoans versus 30,017 cheeseheads. The Bears were still called the Staleys, the league was the American Professional Football Association, and the field of battle was Cubs Park. The cheeseheads at home in Green Bay followed the game over a telegraph set up at a local hall. One year later, the Staleys became the Bears and the APFC became the National Football League. Cubs Park changed its name to Wrigley Field in 1926.

The Bears and Packers are the only truly intact football clubs left standing from those early days of pro football. So the Bears and Packers are the towering first gods of football, like the Titans of Greek mythology. The Bears and Packers are the constellations of the NFL, locked forever on the celestial field of play, or until the expansion of the universe tears their football stars out of orbit around Chicago and Green Bay. Sorry. Clearly I watched too many NFL Films for research.

The vicious unending Bears-Packers series stood at 105 games going into the 1972 season, the year we watch Steve’s young life unravel. It was 165 games going into the 2003 season, as we survey the rubble of Steve’s life as an adult.

Cheesehead

Any resident of the state of Wisconsin, which borders Chicago, Illinois to the north. This can be found in any Chicago dictionary. What do cheeseheads call Chicagoans? All kinds of names, none of them nice I’m sure! The term “FIP” is not uncommon—“Fucking Illinois Person.”

According to the Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board, Wisconsin “has long been synonymous with cheese” and produced over 3 billion pounds of it in 2016, leading its closest state competitor by nearly a billion pounds. In 2017, the Wisconsin state legislature named cheese the official state dairy product in response to a proposal from a fourth grade class at Mineral Point Elementary School in Mineral Point, Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board called the designation “a victory for everyone in the Wisconsin dairy community to celebrate”.

Vince Lombardi (1913-1970)

Legendarily legendary coach of the Green Bay Packers, 1959-1967.

Vince Lombardi wasn’t a coach. He was a folk hero. Vince might as well have walked across the United States in seven-league strides, eighteen feet tall, throwing footballs and pithy motivational quotes at everyone he met.

“It’s not whether you get knocked down, it’s whether you get up!” the giant folk hero Vince Lombardi would shout as he paced America’s sidelines, the length of the continent with goal posts on the East Coast and West Coast. Folk hero Vince always wore his fedora, stepping over houses, tossing footballs and chain-smoking Salems. In colder weather, he added his trenchcoat or his lucky camel’s hair overcoat. People would need eclipse glasses when giant folk hero Vince Lombardi passed by and flashed his trademark grin. They say the gap between his front teeth was wider than the Mississippi. And everywhere a football fell, another pair of goalposts sprouted, and people worked hard, played football, and went to Mass in Catholic churches.

It seemed that way, anyhow, because Vince Lombardi’s Packers conquered football just as the sport catapulted past baseball as the true national past-time—and more importantly, just as televisions started bringing football into American homes like Steve’s bungalow in Roseland at 12426 S. Wabash.

Life-size Vince Lombardi took a floundering, failing small-town team and turned the Green Bay Packers into a football phenomenon that inspired the nation. Lombardi’s Packers won five NFL Championships, the last two title seasons overlapping the start of the Super Bowl—and they won Super Bowl I and II as well. The Packers’ 1965, ’66 and ’67 NFL titles are the first and still the only three-time consecutive winning streak.*

And as sportswriter and official Packers historian Cliff Christl points out, Lombardi’s team won five world championships in just seven years, then a completely unrivaled feat: “Even the ‘Monsters of the Midway,’ the Chicago Bears of the 1940s, won only four in seven years.” **

We’re going to hear so much about Vince as the story progresses, because Steve is such a Vince fan, that we’ll leave it there for now. Vince Lombardi was Catholic and Italian and a huge football hero—that’s the important stuff.

*The 1929-1930-1931 Packers also won three consecutive NFL titles, but not through league playoffs. At that time the title was awarded according to league standings.

**Papa Bear George Halas, who coached his team for a total of 40 seasons, was in charge for the Bears title wins in 1940, 1941 and 1946, but not for 1943. Halas had re-enlisted in the Navy for World War II. Serving in World War I was just a warm up for him.

2001: A Space Odyssey

One of the most influential and weirdest movies of all time, conceived and written by director Stanley Kubrick of Dr. Strangelove fame along with famed science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke. 2001 is a sci-fi history of our ape origins, and a story of the future of mankind. Kubrick filmed it with such maniacal attention to detail that even now, as I write in the early 21st century, every facet of the space ships, space stations, and astronauts look like the latest computer special effects. 2001 is no Star Trek, where heavy metal sliding doors on the spaceship Enterprise are less convincing than the series of steel doors that clang shut behind Maxwell Smart in the opening credits of Get Smart. And both those series were on TV when 2001 was released, in 1968.

Even the 2001 ape tribe sequence is astoundingly realistic, as if a National Geographic team got in a time machine to shoot a TV special. The apes must be people in ape suits, but the ape facial movements and expressions are perfect.

Kubrick’s technical achievement is that much more impressive when you consider that 2001 opened in Chicago against the premiere of Planet of the Apes, starring Roddy McDowell in a rubbery chimpanzee face mask and Charlton Heston, whose facial expressions was only slightly more emotive.

In reality, of course, 2001 was made with 1968 technology, sometimes as simple as hanging astronauts on wires. The gliding space ships and astronauts walking on the moon were so convincing, it made the real Apollo 11 moon landing one year later look like Star Trek to many viewers watching the flickering images on 1960s TVs hooked up to unreliable antennas on the roofs of their houses. Steve’s friend Jack Cassero, in fact, found Chuck Wagon dogfood commercials far more realistic than Neil Armstrong walking on the moon. Not that Jack, or any of Steve’s other friends, went to see 2001. People didn’t understand much about 2001 except that it was a 2 ½ hour movie with almost no plot or dialogue. Most people in Roseland went to see Steve McQueen in Bullitt instead. I don’t blame them. There is not, never has been, and never will be anything cooler than Steve McQueen.

Why talk about 2001 in this context, though? Because even though so few people Steve knew actually ever saw it, and neither did Steve, it is the de facto example they all use for meaning something incredibly futuristic.

The genius of 2001 neither starts nor ends with its special effects. The film begins with two ape tribes warring over a water hole. The losing ape tribe later comes upon a huge black “monolith,” as it will be called. It’s a sleek, perfect rectangle, at least 12 feet high, like a colossal gravestone that hasn’t been engraved yet. The shrieking, jumping apes eventually touch the monolith, and, apparently inspired by it, learn to use bones as tools and clubs. Using their bone weapons, the apes retake their water hole. The ape leader throws his bone into the air in jubilant victory, creating one of the most parodied and iconic film scenes of all time, as the bone tumbles into the sky and turns into a space station orbiting the earth.

Kubrick’s camera covers all the prosaic details of space travel as we watch a scientist travel to a moon base in 2001. Another huge black monolith has been discovered there, buried four million years earlier about forty feet beneath the lunar soil. Kubrick and Clarke’s soaring imaginations only meet their upper limit when it comes to women, who serve as receptionists and stewardesses. Almost all the women wear short skirts. The skirts are not nearly as ludicrous as the female uniforms on the original Star Trek, but some of the 2001 women’s uniforms are the nauseating pink color of Pepto-Bismol. There are three women scientists, but even these women either do not speak, or speak only about the traveling scientist’s wife and cute young daughter.

When the scientists moonwalk in astronaut suits to inspect the monolith, the big black rectangle lets out a high-pitched radio transmission aimed at Jupiter. The film’s next section takes us on the mission to Jupiter eighteen months later to investigate further. The spaceship is run by a self-conscious computer, the HAL 9000, called “Hal.” Without spoiling the rest of the film, let’s just say that what happens when Hal disagrees with the astronauts should scare anyone who is not already concerned about the current drive to develop artificial intelligence (AI). Go watch the movie to see why the last half hour is referred to as the “Star Baby” segment.

Chicago Sun-Times movie critic Roger Ebert, who became the first person to win a Pulitzer Prize for film criticism, gave 2001 his highest rating. When the film appeared in 1968, Ebert was just 26 years old. He’d been working for the Sun-Times for one year. But he wound up his review with the best explanation I’ve yet to see for what many consider the deepest, if weirdest, movie ever made:

“What Kubrick is saying, in the final sequence, apparently, is that man will eventually outgrow his machines, or be drawn beyond them by some cosmic awareness. He will then become a child again, but a child of an infinitely more advanced, more ancient race just as apes once became, to their own dismay, the infant stage of man.”

Other critics hated 2001. The New York Times’ Renata Adler found the film so boring, she used a form of the word 15 times in her review. Adler’s take on 2001 was so contrary, she argues seemingly without sarcasm that Hal was an innocent victim of the astronauts. However, the film’s admirers won out. The British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound magazine’s film critic’s poll of the 50 greatest films of all time puts 2001 at number 6, and its director’s poll puts it at number two.

Kubrick himself refused to explain 2001. As he told Playboy in an interview for its September 1968 issue, “It’s not a message that I ever intend to convey in words. 2001 is a nonverbal experience; out of two hours and 19 minutes of film, there are only a little less than 40 minutes of dialog….How much would we appreciate [the Mona Lisa] today if Leonardo had written at the bottom of the canvas: ‘This lady is smiling slightly because she has rotten teeth’ or ‘because she’s hiding a secret from her lover’?”

In Chicago, 2001 opened exclusively at the downtown (now defunct) Cinestage theater at 180 N. Dearborn--with reserved seating!--on April 11, 1968. The newspaper ads included a form you could cut out and send in with a check or money order to buy advance tickets. 2001 played nonstop at Cinestage until late December 1968, and then finally moved out to neighborhood and suburban theaters in March 1969. That’s how it was back then—movies opened at a downtown theater, and if the movie was really good, it could take months to make it to a neighborhood theater.

2001 was met with puzzlement and mixed reviews at first, but public reaction and critical reception grew steadily more positive. The movie was still playing when the Apollo 10 astronauts went through a mission just short of a moon landing in May 1969. The movie was still playing when the first sequel to Planet of the Apes, Beneath the Planet of the Apes, opened at the Roosevelt Theater in May 1970. And it was still playing when the second sequel to the Planet of the Apes--Escape From the Planet of the Apes--opened at the State-Lake Theater in May 1971.

Steve’s second oldest brother Guido and his best friend Tommy Hanssen took Steve and his friend Smarty Jones to see 2001 at the Ford City shopping mall theater. A movie like 2001 wasn’t likely to show up at the two Roseland theaters—the State at 110th and Michigan Avenue, and the Roseland at 118th and Michigan Avenue—or, as they said in Roseland, “on the Ave.” Steve and Smarty did not want to see 2001: A Space Odyssey, but Guido and Tommy were babysitting, so Steve and Smarty had to go with them. Guido and Tommy promised to do magic tricks for them afterward, if they didn’t talk too much during the movie. “I’m gonna talk anyway,” Smarty said about five minutes in when the apes were foraging for food. “If I don’t talk, I don’t think anybody’s gonna talk for this whole stupid movie.”

Shirley MacClaine

20th century actor known for her tremendous work in such films as Billy Wilder’s The Apartment, but also for her goofy New Age beliefs. Female member of Frank Sinatra’s Rat Pack. Shirley MacClaine cut her hair into a short bob sometime in her 20s, and never changed it again—but on her, that worked. I don’t know if Iz wore her hair in this style for her entire adult life too. I should have asked her.

HOW DID THEY END UP IN CHICAGO: Iz, Eddie Rose and Jews Come to Chicago

I have run out of time and must get this post out. But I’d like to give everyone’s family background as they enter the story, so I will return to insert that Note here.

The Dick Van Dyke Show

Best television situation comedy (sitcom) of the 20th century. Created and often written or directed by the inimitable Carl Reiner, who also played the irascible Alan Brady. The show revolves around Rob Petrie, played by Dick Van Dyke, who is head writer of the comedy variety television hit The Alan Brady Show. Alan Brady and his show are based on real 1950s star Sid Caesar and his program, Your Show of Shows. Carl Reiner was a writer for Your Show of Shows, along with many other comedy luminaries of the mid-20th century, including Mel Brooks (Get Smart).

Jack Benny (1894-1974)

Lovable American comedian who started out in vaudeville and became one of the biggest stars of radio. He was born in Chicago of Jewish immigrants, Meyer and Emma Kubelsky, who were from Poland and Lithuania respectively. The weekly Jack Benny Program aired on radio from 1932 to 1955, and a TV version ran from 1950 to 1965…NOT because Jack Benny was a horrible old star who just wouldn’t go away like Bob Hope, but because Jack Benny was just that good. Find some Jack Benny radio shows on iTunes or where ever—you won’t be sorry. Here’s one place—Old Radio World.

The running jokes that were born and raised on The Jack Benny Show are too numerous to go into, but the “character” Jack Benny played under his own name was ubiquitously known for being astronomically cheap, embarrassingly vain, and completely unable to play the violin he always carried. In keeping with his vanity, “Jack Benny” the character would never admit to his age. He was always 39. Although Jack Benny held up one end of a famous decade-long “feud” with fellow radio comedian Fred Allen, the two were great friends. As Allen once said, “He is my favorite comedian and I hope to be his friend until he is forty. That will be forever.”

HOW DID THEY END UP IN CHICAGO: Maria Alvarado and Mexicans Come to Chicago

Again, time has gotten away from me. I will return to finish this Note in order to place it where Maria first enters Steve’s story.

Jays Potato Chips

Chicago’s favorite local brand of chips: A Pip of a Chip. More later, in the book. Heck, Jays Potato Chips might get their own chapter. They deserve it. Mainly you bought Jays in plastic packages of course, but they also sometimes had promotions with big Jays cans. You could presumably open future plastic packages and pour the chips into the can, but that never happened. You’d open a package and eat it. The cans would be used for things that cans are always used for—holding all kinds of household crap.

As mentioned in the chapter on the Wrigley Building, Jays was originally “Mrs. Japp’s,” but changed its name soon after Pearl Harbor. Back then, there was an apostrophe—but when it switched to “Jays” they cut it out.

Here’s an old Jays can from Steve’s house:

But here’s the real potato chip pièce de résistance—a Mrs. Japp’s can. These you don’t find laying around Steve’s basement. For this, I had to search antique stores and find one to photograph—it cost about $200 as I recall, so I felt a picture was enough.

Dog ‘N Suds

Midwest chain of drive-ins that was, like Steve, exactly as its name sounds: hotdogs and root beer. Dog ‘n Suds started in Champaign, Illinois in 1953 and soon had enough branches that Chicagoans like Bill still remember its creamy root beer foam, in heavy cold glass mugs, with yearning affection. The Dog ‘n Suds logo featured a dog that looked like Walt Disney’s Goofy, but with a hat.

Papa Bear George Halas (1895-1983)

Yes, as mentioned in Chapter 2 (Part 2), Bears founder-owner-coach-player George Halas kicked his own quarterback, Bob Snyder, right in the ass before a game against the Green Bay Packers. He was talking to an enemy player on the field. That was standard Halas.

The Bears were “founded by the unruliest of all, George Halas,” wrote legendary Chicago newspaper columnist Mike Royko in January 1986, as the city buzzed about the rambunctious Bears players who were just about to win Super Bowl XX. Royko went on: “I recall Halas, in his late 60s, seeing a fight break out on the field between his players and the opposition. Did he rush out to quell the violence? Like hell. He grabbed a loose helmet and limped into the brawl, swinging the helmet like a club at the heads of the enemy.”

Here’s Papa Bear in his element, yelling and waving his arms on the sidelines during a Bears game in the ‘60s.

I think there’s a reason his statues—the one outside Bears headquarters in Lake Forest, and the one they finally put outside Soldier Field in 2019--have one arm raised and pointing. It’s the closest they could get to a statue that actually thrashes its arms and swears. Beyond the one raised arm, Halas’s statue looks a lot like Vince Lombardi’s in Green Bay--the 1960s short-brimmed fedora, the heavy glass frames, the overcoat.

But Halas’ legend didn’t grow to Paul Bunyan proportions nationally, towering over America like Vince Lombardi’s. Vince even cast a shadow over Bear country, where a little South Side kid like Steve heard more Lombardi lore than Papa Bear tales. That’s because football skyrocketed to popularity with the advent of television in the late ‘50s and ‘60s, while the Bears’ most dominant era was the 1930s and 40s. By the time Steve was old enough to watch football, Papa Bear had limped off the field—he retired as coach for the last time after the 1967 season.

Mike Royko met George Halas at a book party for a Chicago sportswriter and wrote about it for his November 29, 1971 column. Mike wrote that he’d always figured he might like Halas, because Halas made so many people mad. “It stands to reason that anyone who is disliked by a sizable number of Chicagoans must have good qualities. If he is as bad as people say, why hasn’t he been elected to public office?”

Mike is awed by Papa Bear, who “has the chest of a construction worker” and looks 25 years younger than his actual age of 77. Mike asks Halas what day in his long sports career stands out most. Mike admits that it’s “the most trite question you can ask someone in sports”. But he guesses Halas won’t give the usual trite answer. He’s right. Halas pauses, and two people bark guesses:

First guess:“The 73 to 0 game.”

“That was the amazing score of the 1940 title game,” Mike explains.

Second guess: “Your 100-yard run with the fumble.”

“That was when Halas was still a player,” Mike explains.

But Halas shakes his head and says: “That’s easy. It was when I played for the New York Yankees. Walter Johnson pitched against us that day. He was in his prime. What a fast ball. Nobody ever threw a ball harder. But that day, I hit two balls over the fence off him.” Halas admits both hits were foul.

As he finishes the column, Mike considers how pro football was already at that time a national sports craze:

“You might say it was created by George Halas. He brought it from the sandlots to the super-stadiums, and created most of the techniques that make it so popular. But after all that, he says his biggest thrill was the day he hit a couple of long foul balls. Everybody should have their heads screwed on that straight.”

Under Halas, the Bears won six NFL titles in their dominant years–1932, 1933, 1940, 1941, 1943 and 1946. These teams were the first “Monsters of the Midway,” a nickname appropriated from the University of Chicago football team. Halas coached for four of those six championship seasons. In 1932, he’d temporarily handed the reins to Ralph Jones. He missed 1943 because he was out-of-town—he’d re-enlisted in the Navy for World War II. Serving in World War I was just a warm up for Papa Bear.

Halas sat on the running board of a Hupmobile at the 1920 meeting in a Canton, Ohio car dealership where the National Football League was born, originally called the American Professional Football Association. He played and coached simultaneously until 1929. He coached the team off and on for 40 seasons. He was so elemental to professional football, he was the first to institute daily player practices and watching films of opposing teams.

And Halas was the prime updater of the T-formation in pro football, immortalized in the Bears fight song, sung before every Bears home game, Bear Down, Chicago Bears: “We’ll never forget the way you thrilled the nation with your T-formation. Bear down, Chicago Bears, and let them know why you’re wearing the crown.”

Halas’s 1940 championship win over the then-named Washington Redskins is still the biggest lopsided victory in NFL history—a resounding, astounding 73-0. And everybody heard about it, because it was also the first ever national NFL radio broadcast—carried naturally on Chicago’s own WGN.

How did the Bears gear up to humiliate Washington so thoroughly that the record may never be broken?

Three weeks earlier, the Redskins had squeaked a win over the Bears, 7-3. In the final play of that November game, Bears quarterback Sid Luckman threw to Bears fullback Osmanski in the end zone. According to the Tribune’s Arch Ward, Osmanski “couldn’t lift his arms because of what appeared to be interference” by a Redskins player. “The gun sounded just as the ball bounced off Osmanski’s chest and one of the wildest finishes of the season was history,” wrote Ward. George Halas and the players rushed the field yelling for a penalty on interference—we can assume Papa Bear’s arms were thrashing—but to no avail.

On top of the Redskins’ interference costing them a game-winning touchdown, the Bears lost 80 yards to penalties during the game. “Penalties more than anything else can be blamed for the Bears’ failure in Washington,” the Tribune’s George Strickler would write the next day.

“The Bears are a bunch of crybabies,” Redskins owner George Marshall told reporters after the game. “The Bears are quitters.”

Halas took those newspaper stories and covered the Bears locker room with them before the championship rematch on December 8. Imagine “crybabies” and “quitters” exploding off the walls in big black capital letters, over and over again.

According to Sid Luckman, Halas pointed at the newspapers—how he loved to point—and told the team: “Gentleman, this is what George Preston Marshall thinks of you. I know you are the greatest football team in America. I know it and you know it. I want you to prove that to Mr. Marshall, the Redskins and, above all, the nation.”

In 1994, Bears quarterback Bob Snyder told John Gugger of The Toledo Blade that Halas got so worked up, he cried during the speech—which is saying something, since Papa Bear Halas was no Vince Lombardi.

Papa Bear grew rich but when it came to the Bears, he never got past the days when he had to hustle to fill the seats or literally lose the team. He was, you might say, a regular Jack Benny. You might feel the same way if you were born to poor Bohemian immigrants in Chicago’s South Side Pilsen neighborhood, helped create the National Football League out of nothing, and then barnstormed across the country in 1925 to promote football the way Halas and the Bears did—playing eight games in twelve days during one stretch. Mike Ditka, Bears tight end (1961-1967) and later coach of the 1985 Bears Super Bowl team, famously said Halas “threw nickels around like manhole covers.” According to the Bears official website, Halas “routinely cussed referees and made them pick their game salary off the ground a dollar at a time when he paid them following games.”

“It is seldom how much money we have that indicates how we will spend it. No, it is how we obtained the money,” observed veteran sports writer Frank DeFord of Papa Bear in a 1977 Sports Illustrated profile. DeFord recalled how Halas fought Brian Piccolo over an extra $500 pay during Piccolo’s last season—then paid Piccolo’s medical bills when Piccolo was dying of cancer.

The Twilight Zone

Classic, confounding television series created, hosted and often written by Rod Serling (1924-1975). The original series ran 1959-1964. Rod Serling was an awarding-winning television playwright who basically turned to science fiction to shake off grim 1950s television censors. Racism and politics played better in a world that supposedly didn’t exist.

Twilight Zone episodes fit almost entirely into one or both of two categories: science fiction and atomic holocaust. You could always count on a twist ending in a Twilight Zone episode, one of the show’s unintended ironies. You could also count on Rod Serling to show up and introduce the story, sometimes right in the middle of an early scene, smoking a cigarette, cooler than Frank Sinatra. The camera might pan across a nightclub, and Rod would be smoking a cigarette at one of the little tables. Or the show would start in the woods on a dark winter night, and as the main characters walked off, there was Rod nearby, standing out in the snow smoking a cigarette.

Imagine a child Eddie Rose and his grandparents watching The Twilight Zone some night in the ‘60s, and Rod Serling suddenly appears smoking a cigarette. “He’s Jewish,” Eddie’s grampa would sing out. But Eddie’s gramma would have to admit that Rod Serling did not change his name.

The Exorcist

Bill is talking about the 1973 movie, directed by Chicagoan William Friedkin. Bill never read the best-selling 1971 book by William Blatty (not a Chicagoan, not everyone can be so lucky), but the two stories are essentially the same: A cute, almost angelic little girl named Regan fools around with a Ouija board in her basement, and gets possessed by the devil. Only Father Karras, a Roman Catholic priest and trained psychiatrist who now doubts his own faith, can force Satan out of little Regan—but not before she famously spews green vomit all over the place.

Just as famously, the movie version made many audiences throw up and/or faint. Remember, it was 1973. Much, much, much more Exorcist in Chapter 8: Paul Siciliano, because the book had already been making Catholics sick and afraid for quite some time in 1972, including Steve.

Johnny Carson

Johnny deserves his own chapter and maybe he’ll get one before all’s said and done. But not today. As mentioned in Chapter 2, he was king of late night TV as host of The Tonight Show for 30 years, from the year Steve was born (1962) to 1992 when Steve was almost a father. Johnny always did his monologue in front of gorgeous striped curtains, at least as Steve remembers it.

Johnny’s sidekick Ed McMahon announced him with the famous “Heeeeeeeere’s Johnny!” I bet you don’t know who Johnny Carson is, but you’ve either heard that phrase or heard it parodied and didn’t know it was a parody. Such is time and life.

As a giant star especially in the ‘60s and ‘70s firmament, Johnny of course could have made a fortune off of endorsements. But being Johnny, he went further. Long before Kim Kardashian etc. got out their own clothing lines, Johnny was president of Johnny Carson Apparel, Inc. Below is an ad for his most famous product, Johnny Carson suits. He wasn’t related to the store Carson Pirie Scott’s, but I bet they wished he was. Carson Pirie Scott was a major department store rivaling Marshall Field’s. It was colloquially referred to simply as “Carson’s,” and no doubt they hoped consumers might connect them mentally with the unflappable, funny Johnny Carson.

Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.

This is a famous line from the 1939 movie version of the classic story The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum. It’s from the end, when Dorothy, Scarecrow, Tin Man and the Lion finally make it inside the Wizard of Oz’s throne room. They’re all terrified by the pulsating round green face that appears hovering over the throne, yelling at them—presumably the Wizard of Oz. All but Dorothy’s little dog Toto, who runs over to a nearby curtain and tugs it, revealing a man working an instrument panel. The man is mortified and yells into a microphone, “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!” which simultaneously booms out from the mouth of the pulsating, round green face hovering over the throne.

Bill has no idea that L. Frank Baum actually wrote The Wizard of Oz in 1900 while living in Chicago, a block north of Humboldt Park at 1667 N. Humboldt Boulevard. Bill has simply memorized The Wizard of Oz movie, the way previous generations memorized Bible verses. That’s because The Wizard of Oz is one of a handful of movies so monumentally popular in mid-20th century America that they were shown on television every year, usually around the same time, with lots of advance advertising. It was a family event to sit down and watch these movies annually, kind of like Thanksgiving without a turkey. Ordinary movies were shown randomly every few years or without warning so you’d miss them as often as not. This is why Bill automatically memorized every good line from The Wizard of Oz as opposed to, say, Rod Serling’s forgettable Doomsday Flight.

Pepto-Bismol

In Steve’s day, if you had a stomach-ache of any kind, you took Pepto-Bismol. You would have to take Pepto-Bismol several times a day for years before you went to a doctor to see if perhaps there was a reason for all those stomach-aches. When Steve was a child, the pink glop came in a glass bottle. Later of course, the bottle became plastic. Say what you will about the color or the name: it pretty much always worked.

Calamine Lotion

In Steve’s childhood, the typical drugstore medicine for itchy skin—mosquito bites, poison ivy—was a liberal swab of calamine lotion. Calamine lotion, despite its name, was liquid and also came in glass bottles that gradually gave way to plastic. People generally applied the thin pink liquid with Q-tips and held their limb still until it dried into a crusty film. Today there are far more complicated treatments for itchy mosquito bites, but Steve tells me the Calamine lotion was as good, if not better. For a while at least, until the crusty film crumbled up and fell off.

BONUS QUESTION: How many doors does Maxwell Smart go through to reach CONTROL headquarters?

At least 9: 1, the street door into the building; 2, the doorway he must go through to enter the elevator/stairway, even though we don’t see it; 3, the elevator door he exits to enter the basement hallway; 4, first hallway door, which swings open before him like regular double doors; 5, second hallway door, which slides apart like an elevator; 6, third hallway door, which slides up; 7, fourth hallway door, which slides apart like an elevator; 8, the telephone booth door; 9, the trap door.

NEXT UP, CHAPTER THREE: Me and Steve and Gil

SUBSCRIBE

If you’re not immediately repelled, why not subscribe? It’s free, after all. You’ll receive a new chapter monthly via email, and find out why I am spending so much time on the story of this one guy. You’ll also get a weekly compilation of the daily items on social media: THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, and MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY.

And why not SHARE?

Maybe you know someone else who would enjoy reading about a ten-year-old Italian-American kid on the South Side of Chicago in 1972. Didn’t your parents teach you to share?

"...Millennial Park."

Caught between the picture of the IC tracks and the Pru...as you know, it's "Millennium" Park.