Chapter Two Notes, Part 1: Trump Tower, the Sun-Times Building, Cheese and Hogs

Not your father's footnotes. Fun.

Chapter Two of Roseland, Chicago: 1972 begins by following the sun’s rays poking west down the Chicago River at dawn—crossing the Michigan Avenue Bridge and passing over the Wrigley Building, Trump Tower, the IBM Building, and finally Marina City. Chapter Notes always follow the action of the story, so this first installment of Chapter Two Notes covers the Wrigley Building, then moves on to the site currently occupied by Trump Tower. For more on the Wrigley Building, see its Optional History Chapter here. For the IBM Building and Marina City, see Chapter Two Notes Part 2.

The Michigan Avenue/Du Sable Bridge and the Wrigley Building

William Wrigley Jr. came to Chicago in 1891 and created the biggest gum company in the 20th century world, churning out Wrigley’s Spearmint, Doublemint and Juicy Fruit. Wrigley made a pile of money, bought the Chicago Cubs baseball team and renamed their park Wrigley Field. Finally, he built the Wrigley Building as his company headquarters.

By day, the Wrigley Building is a bright, beautiful butterfly of a building hovering over the urban prairie; by night, a glowing, luminous moth perpetually drawn to the blazing floodlights trained on it.

Architect Charles Beersman ordered six shades of white terra cotta tiles to cover the Wrigley Building, growing progressively lighter toward the top. “The idea was that it would look like the sun was always shining on the building’s upper stories,” emeritus City of Chicago Cultural Historian Tim Samuelson explains. “In later years, I fished damaged pieces of the terra cotta from the dumpster behind the building when repairs were being made. When pieces removed from the top were placed next to pieces from the bottom, you definitely could see the difference.”

And yes, Chicago’s official Cultural Historian really goes dumpster diving for pieces of the Wrigley Building. You should see some of the other stuff he’s dug out of actual garbage dumps and buildings under demolition.

The best place to view the Wrigley Building is from the Du Sable Bridge, due east. The bridge opened in 1920 as the Michigan Avenue Bridge and was rechristened 90 years later in 2010 for Jean Baptiste Pointe Du Sable, the first permanent resident in what would become Chicago. Since our story is happening in 2003, it’s still the Michigan Avenue Bridge in this book.

Remember how the morning sun had to cross the Michigan Avenue Bridge, at the start of Chapter 2, to reach the Wrigley Building? It’s an apt image, because without this bridge, there wouldn’t be a Wrigley Building as we know it.

For much more, see the Wrigley Building’s Optional History Chapter. Part 1 is here, Part 2 is here, and Part 3 is here.

Wrigley Building: Architect Charles Beersman of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, a successor to Daniel Burnham’s firm; south tower with clock completed April 1921, north tower completed May 1924; 400 and 410 N. Michigan Avenue. Bridge: Architect Edward H. Bennett with Thomas G. Pihlfeldt, city bridge engineer and Hugh Young, engineer of bridge design, 1920

Trump Tower, the Sun-Times Building, Cheese and Hogs

As the prairie erupted into Chicago, the plot of land that would become 401 N. Wabash turned into a hog packinghouse, even before the city’s incorporation in 1836. Sylvester Marsh owned and operated one of Chicago’s first hog packinghouses. Always remember that when you look at Trump Tower.

“By 1836, the year before Chicago’s incorporation as a city, Marsh alone processed 6,000 hogs” on the site, according to Chicago historian Dominic Pacyga’s wonderful history of the city’s meatpacking industry, Slaughterhouse.

The hogs left the riverbank with the rest of Chicago’s meatpacking companies in 1865, when the Union Stock Yard opened on the South Side. Eventually an eight-story warehouse went up on the land. J.L. Kraft & Bros. Company leased the warehouse in 1920 for a combination headquarters, small factory, and laboratory. You may have heard of Kraft.

In 1920, Kraft’s main Chicago factory was already located at 505 N. Sacramento, pumping out 75,000 pounds of cheese daily, and it ran four more factories around the country. The Tribune called Kraft “the world’s largest cheese makers.” How did J.L. Kraft manage that?

Like Wrigley, Kraft was an early 20th century corporate giant. The legend of James Lewis Kraft has him showing up in Chicago in 1903 or 1904 with nothing but $65 in his pocket. Kraft either rented or bought an old horse and wagon and started delivering cheese from Chicago’s South Water market to grocery stores around the city. Kraft’s five brothers quickly joined him and formed the company.

And then came their big breakthrough: Kraft invented and patented a pasteurization process to package cheese in tin cans without refrigeration—just in time for World War I. Allied soldiers ate tons of Kraft cheese tins. Then Kraft introduced (or inflicted upon the world, depending on your perspective) Velveeta, Miracle Whip and the iconic instant Kraft Macaroni & Cheese “dinner.”

William Wrigley made it to Chicago for the 1893 Columbian Exposition. J.L. Kraft made do with the 1933-34 Century of Progress World’s Fair celebrating Chicago’s 100th birthday as an official town. Here’s a Kraft pamphlet from the fair, front and back, plus a bonus recipe:

According to emeritus City of Chicago Cultural Historian Tim Samuelson, that all happened in Kraft’s riverside laboratory, right next to the stunning, brand-new Wrigley Building. At that time, the Chicago Tribune called Kraft “the largest producer of ‘package cheese’ in the world.”

Kraft had been eyeing a headquarters spot at Oak and Crosby, but he chose the north riverbank between Wabash and Rush instead. He decided a warehouse in full view of everyone driving across the new Michigan Avenue Bridge “would offer better opportunities for whopping up the merits of cheese,” as the Tribune explained at the time. “Huge electric advertising sign” would be “erected on the roof of the warehouse and on the side walls.”

“The end of the world was spelled out in two significant developments originating in Chicago,” says Tim Samuelson. “Enrico Fermi’s self-sustained nuclear reaction under Stagg Field in Hyde Park, and Kraft’s development of processed food at Wabash and the river.”

By the ‘50s, the now monster Kraft corporation moved its headquarters a few blocks east to 510 N. Peshtigo Court and built the Kraft Building, since obliterated for a glass high-rise. There, they perfected a method to cool cheese in thin sheets, then stack and package them together as pre-sliced Kraft DeLuxe American Cheese Slices. Considering the unnatural hue, you might think Kraft invented the color of American cheese too, if the color hadn’t already existed on the Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit label.

Like fellow Chicagoan William Wrigley, J.L. Kraft knew modern business meant modern advertising. Kraft sponsored Kraft Music Hall on the radio, and instantly jumped into the new medium of television with Kraft Television Theater in 1947. Tribune television columnist Larry Wolters called Kraft Television Theater the oldest continuous dramatic television show when it celebrated its fifth anniversary—and it lasted 11 years. Some of the luminaries who worked on the show include writer Rod Serling, who would go on to create The Twilight Zone; and actors Peter Falk (Columbo), Margaret Hamilton (Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz), John Cassavetes (Rosemary’s Baby, and a great turn on a Columbo episode, among so many), William Shatner (Captain Kirk on Star Trek, as well as the guy on the famous Twilight Zone episode who’s afraid to fly and thinks there’s a caveman on the wing of the plane he’s flying in, trying to destroy the engine), and ventriloquist Edgar Bergen with his dummy Charlie McCarthy.

“We have a half dozen (television) sets around the house,” Bob Hope claimed in 1951. “We even bought one for the cat. It’s a miniature set that he can carry in his mouth. It does my heart good to watch him tote it across the room, place it in front of the nearest mouse hole, then tune in the Kraft commercials.” Bob Hope was the biggest comedian of his time. And that was as good as he got.

What happened to this piece of ground after Kraft left? Field Enterprises—owned by the scions of Chicago’s most famous departent store, Marshall Field’s—bought the site to build a headquarters for the Field-owned Chicago Sun-Times. On November 16, 1955, Marshall Field Jr. hosted a ground-breaking luncheon at the Palmer House for 500 guests, including Mayor Richard J. Daley and Illinois Gov. Stratton. Nothing in mid-20th century Chicago was complete without a tie-in to the real Mayor Daley.

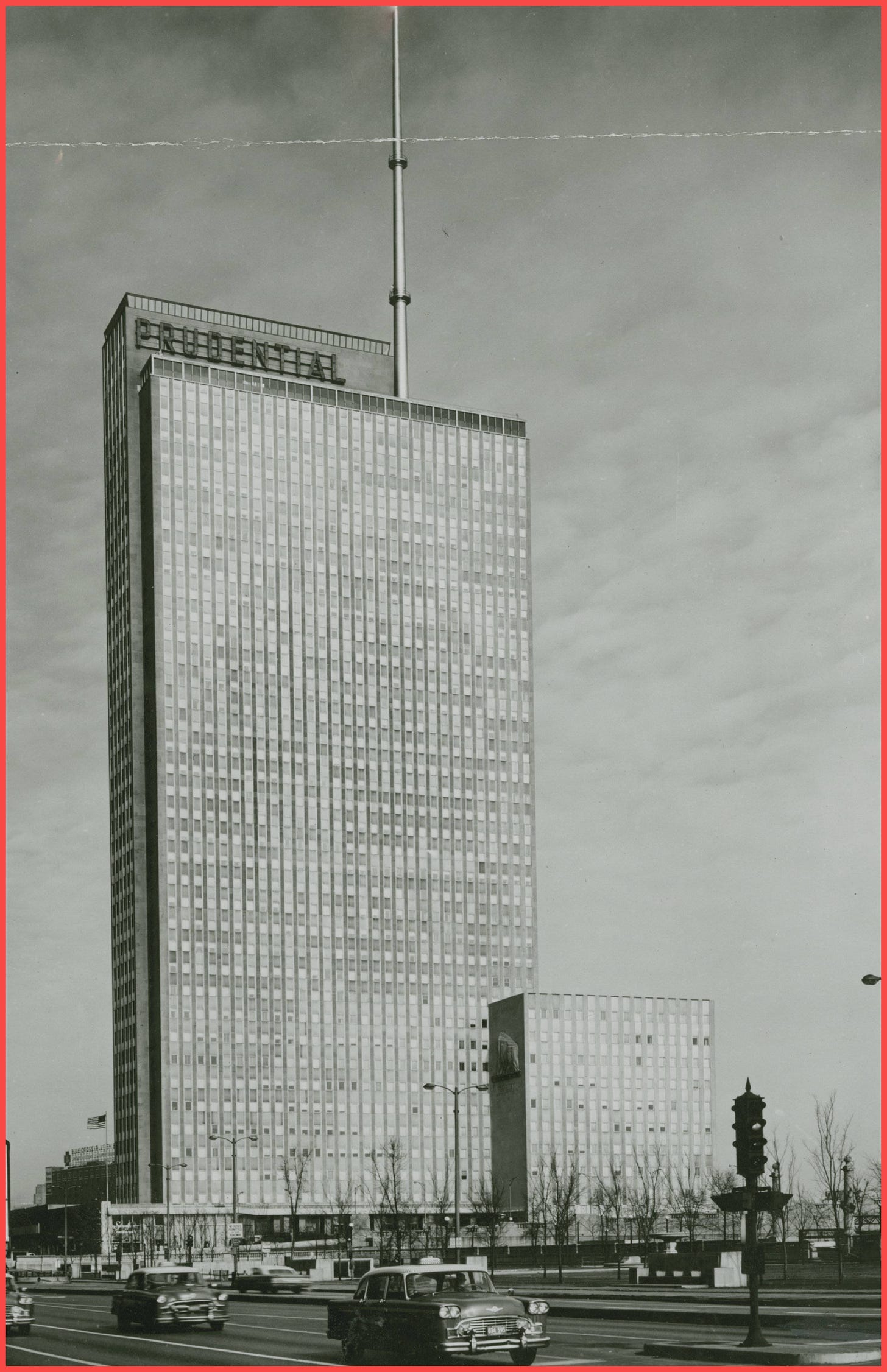

Technically, the Sun-Times headquarters must have been built, but really, it looked like they drove a barge up the river and lashed it to a dock in 1957. Many people might not consider that the Sun-Times Building had an architect, but of course it did. The Sun-Times Building was designed by the prominent firm Naess & Murphy, which had recently created the then-much admired Prudential Building at the southwest corner of Grant Park.

You can see how the Sun-Times Building was sort of like cutting nine stories out of the middle of the Prudential and slapping it down on the riverbank. The American Institute of Architects Guide to Chicago gives the Sun-Times Building exactly one sentence, calling it “an undistinguished building”.

Soon after the Sun-Times Building opened, Field Enterprises bought the Chicago Daily News, sold that paper’s gorgeous Art Deco headquarters with the first attached plaza on the Chicago River, and moved the News staff into the new digs farther up the river. Let’s just take a quick look at what the Fields threw aside for a new model:

After the move, both newspapers’ names ran across the top of the Sun-Times Building in cheesy yellow letters, until the Daily News folded in 1978. Radio, television, and a dwindling public interest in real journalism had been killing off newspapers already for a couple of decades. After the internet came along to throttle newspapers even harder, the then-current owners of the Sun-Times cashed in on their prime piece of real estate and sold it to Donald Trump in 2001.

Like many of our own relatives, the Sun-Times Building left a much bigger hole in Chicago’s heart after it was gone than it had taken up during its lifetime. I think there are two reasons for that.

First, it was solidly and reassuringly always there when you crossed the Michigan Avenue Bridge or the Wabash Bridge. You could count on it, like an aunt who maybe isn’t much fun but always sticks a nice crisp $20 bill in your birthday card.

Second, you could walk the entire length of the Sun-Times Building on the ground level through a public corridor partially lined with huge windows, which overlooked the massive basement printing presses, manned by actual pressmen, who produced the newspaper right there in front of your eyes. I wish I’d taken pictures of that, but at the time it just seemed normal. I never thought it would disappear. Again, like our own relatives.

“I miss seeing it hunker on its oddly-shaped lot jutting into the river,” says emeritus Chicago Cultural Historian Tim Samuelson. “Not a pretty term at all, but that’s exactly what it did—and it hunkered well.”

For context, let’s look again at the old curled up postcard from Chapter Two. There’s the Sun-Times Building in the lower right corner, with its cheesey yellow sign’s letters at the top, and a big barge appropriately pulled up alongside it.

[NOTE: Thanks to a reader comment, I’m told the Sun-Times Building had a barge pulled up alongside it for a months at a time—loaded with big rolls of newsprint.]

The city worried itself to death about Trump Tower Chicago—after the unholy coming of Donald Trump was announced in 2001, and throughout the years it was being built. It takes time to put up a 92-story building on a rather small plot of land right next to a river. But Trump Tower finished in 2009 as an elegant, worthy addition to the skyline, designed by Adrian Smith, then of Skidmore, Owings and & Merrill (SOM). The Chicago Architecture Foundation writes that Trump Tower “communicates its relationship” to its three iconic neighbors with its three sections: The 16-story base matches the height of the Wrigley Building to its east; the second, 29-story section “points north toward River Plaza and west to Marina City”; and the third 51-story tower section relates to Mies Van der Rohe’s IBM Building, just across the street.

If they say so; I would just say it’s easy on the eyes. Or was, until Trump went and put his name on it in blaring tinny 20-foot high letters. That 20-foot high name, he told The Wall Street Journal, “happens to be great for Chicago because I have the hottest brand in the world.”

Chicago architecture critic Lynn Becker observed that the letters “look astoundingly cheap, like those you’d find in a child’s magnetic letter set, bleached of color.” As Becker noted, “You normally don’t want to bring attention to the continuous strip of metal louvers of a service floor interrupting a sleek glass curtain wall façade but that’s exactly what the 141-foot-strip of letters does, drawing your eye to a visual interruption that would otherwise be subsumed into the larger mass of the building.”

But as Becker wisely concluded, there was no point getting hysterical about the Trump sign. There were plenty of worse outrages going on in the city that year. We can add that goes for now too, and always.

Still, the Trump sign debacle makes you appreciate William Wrigley Jr. that much more. Wrigley understood the power of brand and advertising, too. God knows he put his name all over his various brands of gum. It was never just “Spearmint,” “Juicy Fruit.” It was “Wrigley’s Spearmint” and “Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit.” During a national financial crisis in 1907, Wrigley mortgaged himself to the hilt for a $250,000 loan to buy discounted advertising worth $1.5 million and drum up business. That took real guts.

And yet: What is the one thing you do not see when you look at the Wrigley Building? Answer: The name of the man who built it. Now that’s a legacy you can respect—like Julius Rosenwald passing on putting his name on the Museum of Science and Industry.

“When one realizes that Mr. Wrigley pays a good fraction of a million dollars annually just to let the mazdas flash the fame of his gum to Times Square passersby in Manhattan,” wrote the Tribune in 1920, “his modesty and restraint in keeping snaky electrical advertisements from luring the eye of the boulvardier in Chicago to his magnificent building is something to commend.”

In contrast, since Donald Trump added his name in 20-foot tall back-lit lights 200 feet above the ground to Trump Tower Chicago, Tim Samuelson says the building now lives up to the site’s history: It’s The Cheeziest! That’s a classic Kraft advertising slogan, for younger readers.

You may be wondering: Since our story takes place in 2003, and Trump Tower didn’t go up until 2009, why has Steve already changed his morning walk up Wabash so he can avoid looking at the 20-foot-high letters spelling “Trump”? This is one of those odd discrepancies I mentioned in Chapter One. People’s memories, as I said, can be flat out crazy. Everyone I talked to for Steve’s story insisted Trump Tower was already there during the crucial events of Steve’s life in 2003, including Steve. Trump and the Sun-Times owners did announce Trump Tower in 2001, but they didn’t tear down the Sun-Times Building until 2004. How to explain this curious anomaly? I think in 2003, everyone was living under a Trump-shaped mushroom cloud. Later, they lived in the fall-out. Later still, the country and the entire world lived in the Trump fall-out.

Here it is, one more time, as Steve saw it when he still walked north up Wabash.

Trump Tower: Architect Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 2009; 401 N. Wabash. Sun-Times Building: Architect Naess & Murphy, 1957; 401 N. Wabash

Coming NEXT in Chapter 2 Notes: The IBM Building & Marina City. And don’t forget The Wrigley Building’s Optional History Chapter—if you missed it, find it here.

SUBSCRIBE

If you’re not immediately repelled, why not subscribe? You’ll receive a new chapter of “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” every month in your email box, along with a weekly compilation of the daily items on social media: THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, and MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY.

And why not SHARE?

Maybe you know someone else who would enjoy reading about a 10-year-old Italian-American kid on the South Side of Chicago in 1972. Didn’t your parents teach you to share?

we'll, no, it's not as "Steve saw it...", not in 2003.

It's how Steve's friends remembered it, years later I say the photo caption should be revised.