The Wrigley Building, Part 3: When Chicago Wasn't Chicago

OPTIONAL HISTORY CHAPTER

If you’re not a regular reader of this site, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” is a serialized novel/1972 Chicago primer. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972. Each chapter comes with fun Notes on key topics that pop up as our story progresses. This is the final installment of an Optional History Chapter on the Wrigley Building, which makes its first appearance in Chapter 2. “Part 1: William Wrigley Jr. Conquers the World” is here, and “Part 2: Built on Spearmint,” is here. To find out what the novel is all about, see here. Part 1 of the general Notes to Chapter Two is here.

Let’s skip the part where a swirling cloud of cosmic dust takes billions of years to coalesce into a planet. Even then, “the shaping of Chicago’s physical environment was an aeons-long process,” writes Donald L. Miller in his marvelous history, City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America.

Cut to the middle of the last Ice Age, about a million years ago, when Miller describes how “huge ice fields…drifted down from Greenland and blanketed the entire northern half of the continent, putting areas around Chicago a mile deep under layers of ice and debris. At least four successive glaciers advanced and retreated, flattening hills, filling valleys, gouging out enormous basins.”

A final ice sheet, the Wisconsin Drift, receded some 12,000-13,000 years ago, writes Miller, and “reconfigured the entire mid-continent.” At first, this included a gigantic “Lake Chicago” that included in its vast waters what we know today as Lake Michigan. To grossly simplify everything, after the water receded, we were left with the lake, prairies and marshes, already thousands of years old by the time people arrived in North America.

We used to think people got here about 14,000 years ago, on foot across an ancient land bridge connecting Asia and Alaska. But in 2021, scientists discovered footprints in New Mexico potentially 23,000 years old, based on pollen imbedded in the prints. A re-analysis released in October 2023 confirmed their finding, and who knows what will come next?

We rejoin the story in the 1600s. Ann Durkin Keating’s fascinating book “Rising Up from Indian Country” describes this transitional period when European settlers spread across the Midwest and Native American Indian tribes were pushed and pulled by many forces. The different populations mixed and coexisted both easily and uneasily.

Fur trade competition among Native American Indians had already changed tribal territories by the time French Jesuit priest Father Jacques Marquette and explorer Louis Joliet set foot in today’s Chicago area in 1673, writes Keating:

The “Iroquois Confederacy, a major partner of the Dutch and then the British in the fur trade pushed many Algonquian tribes westward into the Great Lakes in their quest to control the available supply of beaver skins. Groups like the Potawatomis, who had lived around the St. Lawrence River, found themselves refugees on the western shore of Lake Michigan. The French offered aid from Green Bay, eventually the Iroquois threat was quelled, and the Potawatomis and their allies moved southward and eastward.”

By 1800, she writes, “The Potawatomis, Odawas, and Ojibwas shared control of Lake Michigan”.

At this point, the shores of Lake Michigan and its surrounding region were “an ever-changing weave of native villages and colonial outposts that together made up” what was called “Indian Country,” writes Keating. So there were no permanent settlements in the area around the mouth of the Chicago River where the city would begin.

Indian villages, explains Keating, “regularly relocated in the face of changing seasons and conditions. People built housing not to last for a lifetime or more, but for a season or two. Real estate was not bought and sold. Instead, the control of resources ordered society (and led to many of its conflicts).”

And how did the city’s settlement by non-Native Americans begin? The first such settler was Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable. There are many ways to spell his name, but we’ll go with the spelling chosen by Chicago when it officially added his name to iconic Lake Shore Drive in 2021, after sometimes acrimonious debate.

It may seem odd that Chicago should be so focused on this question now, when it has become common among many organizations, especially universities, to begin meetings or lectures with “land acknowledgements” naming the Native American tribes who lived in their regions before colonization and the spread of the United States across the continent.

Why should anyone today think it important to identify a single person who is not Native American to credit with “founding” Chicago—or consider it a credit to make that person responsible for beginning the process of banishing Native Americans from any particular place?

And why, in an era when women are supposedly considered equal to men, would we automatically consider Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable the founder of Chicago and not also his Potawatomi wife, Kittihawa (Catherine), who settled the homestead with him and was indispensable to his work?

The whole subject is, as people like to say these days, problematic. But DuSable’s recognition remains an issue because through much of Chicago’s history, when U.S. cities routinely celebrated non-Native American, always male founders, Chicago did not give that honor to DuSable, and did not erect monuments for him.

Of course racism was a large part of DuSable’s late recognition. DuSable was either entirely of African descent or biracial, and it took about a century for Chicago to officially name him as its first settler rather than John Kinzie, a British-Canadian boozy brawler who bought DuSable’s homestead. More on that in a bit.

Neither DuSable or Kinzie ever meant to establish an American city and bring an end to the Indian Country in which they thrived. That doesn’t seem to matter to anyone, however.

Today, there are many recognitions for DuSable—the museum of African-American history here that bears his name; the bronze bust shown above and National Historic Landmark plaque on the site of his homestead; the Michigan Avenue Bridge, renamed for DuSable in 2010; the harbor at the foot of Randolph Street; and a three-acre peninsula nearby that unfortunately has been waiting to be developed into DuSable Park since 1987.

Still, Ald. David Moore (17th) sponsored the recent Lake Shore Drive renaming after taking an architectural boat tour on the Chicago River because, he said, the guide didn’t mention DuSable. “That infuriated me,” he said.

Native Americans may see it differently. “Calling [DuSable] the city’s founder ignores the hundreds of years that Indian tribes used this place as a major trading spot, a center for all manner of commerce and travel,” Les Begay, the chairman of Chicago’s American Indian Center board and a member of the Diné Nation, told the Chicago Tribune’s Rick Kogan in 2019 as the debate began over renaming Lake Shore Drive for DuSable. (It is almost impossible to write about a Chicago topic that hasn’t already been covered by Rick Kogan, either in the Chicago Daily News, the Chicago Sun-Times, or the Chicago Tribune. He gets around.)

Without assigning credit or blame, we can say today that DuSable built the first permanent home in future Chicago with his wife Kittihawa (aka Catherine), who was likely Potawatomi. They settled on the north bank of the Chicago River, in the area now covered by the Equitable Building’s Pioneer Plaza and the Apple store, on the east side of today’s Michigan Avenue.

Ann Durkin Keating tells a considerably more complicated story about the network of European, Indian, and mixed traders and residents of the region at that time. However, she says, DuSable and his wife established their home and trading post on the Chicago River north bank by 1788, and lived there for 12 years. It was a “complex of buildings” including a blacksmith shop. Other accounts often put the DuSables on that site by 1780.

There are many competing stories about DuSable’s ancestry and how he came to settle on the Chicago River’s north bank. There is no definitive, proven version of DuSable’s origins, and no drawings of the real man. A popular account is that DuSable came from Haiti, the son of a Haitian slave woman and a French mariner, but it is only one account.

“Point de Sable was a French-speaking, mixed-race, practicing Catholic who married an Indian woman and traded around Lake Michigan for nearly thirty years,” writes Keating. She says evidence “suggests that he was born before 1746 in or near Kaskaskia, a French settlement along the Illinois River.” The settlement at that time included French, Native Americans, and both black and Indian slaves. A French couple there “held as slaves a woman named Catherine and her son Jean,” and got permission from the French colonial government to free both after their own deaths. Jean was the correct age to become the trader now known as the founder of Chicago.

In 2003, during one phase of the attempt to develop DuSable Park at the mouth of the Chicago River, the Tribune’s Celeste Garrett reported that one of the obstacles was that the steering committee members couldn’t agree on “DuSable’s origins, including his parentage, place of birth and even whether he founded the area now called Chicago.”

At that time, Garrett wrote, the city’s Department of Human Relations claimed that DuSable “was a fur trader born in Haiti who spoke five languages and averted a war by negotiating a peace treaty in 1769 among feuding native American tribes in the great lakes region.” But Chicago Historical Society (now Chicago History Museum) DuSable expert Ralph Pugh said there was no evidence of DuSable negotiating a treaty.

“This is the tricky thing about DuSable,” Pugh told the Tribune. “Because he has become politically important, facts are often said about him without challenge, which actually does a disservice to a great man who is quite historically important.”

Pugh said DuSable was important as “the first major player” here of African descent, and because he was a businessman known at the time as a “straight dealer.” The most accepted story of DuSable’s background, according to Pugh, has him born in Canada of two free Black people, coming to Illinois from Detroit, and establishing his homestead on the Chicago River’s north bank in 1785.

Regardless of DuSable’s early life, he definitely became a fur trader, ending up in what is now Michigan City during the American Revolution, then managing a British outpost north of Detroit. He and his wife settled here in the 1780s, building the first permanent structures.

Keating says quite soon after arriving, the DuSables had many new neighbors. They included Antoine and Archange Ouilmette, just to the west, where the Wrigley Building now stands.

Antoine Ouilmette was a French trader and farmer from outside Montreal, and Archange was French and Potawatomi, living in the Calumet region when they married.

“After settling at Chicago, Ouilmette continued the often-backbreaking work of transporting travelers and their baggage across the Chicago portage (linking the south branch of the Chicago River to the Des Plaines River through an area known as Mud Lake),” writes Keating. She says the Ouilmettes moved from Chicago in the 1820s, to property they owned in Gross Point—now Wilmette, where they “raised their children and operated a substantial farm.”

In 1795, an array of Native American Indian tribes negotiated the Greenville Treaty with the United States. The Potawatomi ceded several small areas in that treaty, including six square miles at the mouth of the Chicago River and the DuSable homestead. Soon after—by 1800—DuSable left, selling his land and cabin to French trader Jean La Lime.

La Lime seems to be Chicago’s First Real Estate Flipper, selling the land to fur trader John Kinzie in 1803. Kinzie lived in DuSable’s cabin just as the U.S. army arrived to build Fort Dearborn, across the river on the south bank. In fact, workers digging the foundation of the Wrigley Building’s north tower found a wooden sidewalk and box sewer about fifteen feet down. Chicago library historians identified it as a sidewalk built by Kinzie, leading from DuSable’s cabin to a landing for a ferry, which shuttled north riverbank settlers to Fort Dearborn.

Fort Dearborn was located on the land radiating from what is now the southeast corner of the Michigan Avenue/DuSable Bridge. That’s now the intersection of Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive, the street which runs along the river on its south bank. On the southeast corner of the intersection, note the lovely 333 N. Michigan Building. You’ll know it by the Fannie May candy store right there on the corner. Nip inside the main lobby if you can to look at the beautiful metal work on the elevators.

If you look down as you pass by, you’ll see there are several bronze plaques set in the sidewalk—and even the pedestrian island in the middle of Wacker Drive—marking the approximate original site of Fort Dearborn.

Below, there’s the southeast corner of Michigan and Wacker on a November afternoon. You hardly ever see people appear to notice the metal plaques embedded in the sidewalk, even though they’re often looking down, especially in cold weather.

DuSable left Chicago before Fort Dearborn was built in 1803, and he also got out in time to miss what would become known as “The Fort Dearborn Massacre” on August 15, 1812. That’s probably not a coincidence.

Keating believes DuSable left in part due to the anti-American sentiment and unrest among the area’s Native American population after the 1795 Greenville Treaty. DuSable would have been keenly aware of the situation, because he was working as a U.S. government interpreter by 1798. In addition, DuSable’s wife and daughter had died before 1800, so operating his property would have become difficult.

When DuSable first built his homestead in the 1780s, Keating writes, the spot was an “unexceptional,” normal place for one of the many trading outposts in the region. But—“After the Greenville Treaty, it became a symbol of an imposed colonial presence.”

The so-called Fort Dearborn Massacre is a complicated story of misunderstandings and competing interests, thoroughly explored in Keating’s book. Bottomline, restless Potawatomi saw a chance to push out U.S. government forces when British soldiers scored big early victories in the war of 1812. Potawatomi warriors were camping around the Fort Dearborn when its leader, Captain Heald, was ordered to evacuate due to the war with the British.

Captain Heald was headed to Fort Wayne the morning of August 15, 1812 with his 56 soldiers, along with 12 militia members, 9 women and 18 children. They were attacked by about 500 Potawatomi warriors along the shore of Lake Michigan, which at the time was around Prairie or Calumet Avenue, somewhere between what’s now 12th to 15thStreet.

By all accounts it was a bloody battle, mostly over within 15 minutes. And the killing went beyond the adult male combatants. The Potawatomi wanted the company’s supplies, which had been left next to the wagons filled with women and children.

“The Potawatomi warriors sought the booty held in the supply wagon, and many children wound up in their path,” Keating writes. “One young Indian, filled with drink and fury against his fallen comrades, ‘killed several children with his tomahawk.’”

Three women and 12 children died. Captain Heald, wounded and captured, reported that 15 Potawatomi were killed, and 38 of his own men. Captain William Wells and a small contingent of Miami warriors had been sent to accompany the retreating Ft. Dearborn group. Wells died by gunshot, and the Potawatomis then scalped him, cut out his heart, and divided it among themselves to eat.

The Potawatomis later burned down Fort Dearborn, but U.S. soldiers returned to rebuild in 1816. The Potawatomis left for good following the 1833 Treaty of Chicago.

As Keating sums it up, “While the western Indians won the battle at Chicago in August 1812, they lost the wider war when the British abandoned them to negotiate on their own with the United States. Between 1815 and 1833, the Potawatomis ceded all of their lands, some five million acres, to the United States. They accepted reservation lands in U.S. territory, while only forty years before the U.S. government had sought outposts in Indian Country.”

DuSable vs. Kinzie

As we mentioned earlier, neither man called the “founder” of Chicago—Kinzie or DuSable—had any interest in ending Indian Country and establishing a purely U.S. territory, says Keating. But facts rarely get in the way of myth. The question is, why did Kinzie get the distinction for so long?

For decades, John Kinzie was called Chicago’s founding father or “Chicago’s first white settler”—even though Kinzie was also Chicago’s first murderer.* People naturally assume Kinzie got his unearned honor due to racism alone. But this doesn’t account for the social-climbing and self-aggrandizement also central to our lovely human nature.

As Miller’s City of the Century recounts, Kinzie’s ambitious daughter-in-law Juliette Magill Kinzie wrote and promoted her own early history of the city, featuring a starring role for a cleaned-up John Kinzie. She “wanted to be known and remembered as part of a Chicago family dynasty”. Since DuSable had left 33 years before the settlement even became a town, he was easily forgotten, regardless of his background, with a motivated booster like Juliette pushing Kinzie.

Juliette Magill Kinzie’s version of Chicago’s early settlement held for about a hundred years. In 1903, the Tribune covered city celebrations for the “centennial” of the “first settlement” of Chicago, which they dated from the year 1803, when Kinzie bought DuSable’s land from Jean La Lime. That obviously makes no sense, since the Tribune itself acknowledged that Kinzie bought a piece of land with a permanent structure already erected on it.

Oddly, only seven years later in 1910, the Tribune called DuSable “the first man to acquire title to Chicago real estate, which has held good to this day, and was for this reason our first city father—Chicago’s first landed citizen.” DuSable’s significance faded within 20 years, though, since it took the work of several African-American groups to make sure Chicago’s 1932-33 World’s Fair, A Century of Progress, included an imagined reproduction of DuSable’s cabin and called him “Chicago’s first citizen.”

Then, Chicago leaders “forgot” about DuSable all over again. Chicago’s African-American community worked for DuSable’s recognition throughout the early 20th century. Finally, Mayor Richard J. Daley set up the Chicago DuSable Committee in 1969. The committee’s high-profile chairmen and committee members were charged with figuring out an appropriate memorial for DuSable, and where to put it. However, a classic Mayor Daley political tactic involved creating prestigious committees or commissions for something he didn’t want to do. Then the committee or commission would quietly die. If the committee or commission managed to produce a report and recommendations for something Mayor Daley didn’t want to do, he could pretend to warmly accept the findings—and let it all quietly die.

In 1971, Chicago Daily News columnist Lutrelle “Lu” Palmer, a legendary African-American reporter and later activist, checked to see how the DuSable memorial was coming along. He found the committee’s office occupied by a completely different business. The committee’s phone number forwarded to a new number, which forwarded to a third number.

“Nobody at the last number has ever heard of the Chicago DuSable Committee,” wrote Palmer.

In 1971, Palmer noted, Chicago had named one school after DuSable, and an alley. Though Palmer didn’t mention it, John Kinzie had a street named for him in time for an 1834 map of Chicago—an east-west street just north of the Chicago River’s main branch.

Palmer called the high profile DuSable committee chairmen and members, but nobody knew what was going on with establishing a DuSable memorial. Only fiery independent Ald. Leon Despres of the 5th Ward was typically forthright: “What’s happened with the committee? Absolutely nothing.”

Slowly, new designations for DuSable grew anyway. Prominent Chicago African-American educator and historian Margaret Burroughs had already founded the DuSable Museum of African-American History in 1961 in her own home, and in 1974 Mayor Daley’s Chicago Park District gave the museum the Washington Park fieldhouse. Mayor Daley even became an honorary board member.

The site of DuSable’s original homestead was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976, and an explanatory bronze marker added to Pioneer Plaza. In 2009, a private donor funded a bronze bust of DuSable for Pioneer Plaza. A year later, the Michigan Avenue Bridge overlooking both the Wrigley Building and DuSable’s original homestead was renamed the DuSable Bridge. DuSable Park was named in 1987, though it’s still unfinished, and now there is Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable Lake Shore Drive.

To me, the renaming of the Michigan Avenue Bridge is the most fitting memorial for DuSable—it’s just unfortunate that it does not include Kittihawa. Have you noticed how often the Michigan Avenue/now DuSable Bridge comes up in any discussion of the Wrigley Building? It’s practically an extension of the Wrigley Building. As we’ve discussed throughout this chapter, without the DuSable Bridge, there would be no Wrigley Building. At least not as we know it.

If Chicago hadn’t finally started building the Michigan Avenue Bridge in 1918, would William Wrigley Jr. have bought land for his world headquarters on the north bank of the Chicago River? Not bloody likely. And he surely would not have bought a crazy piece of land that required constructing a building without a single right angle at its four corners.

No; without the bridge, the Wrigley Building would be a typical building on a typical square city lot, made of boring angles and buried in the Loop among blocks of other early skyscrapers--not the shining river beacon we know today.

And where does every Chicagoan, and every visitor to Chicago, stand to admire the Wrigley Building, beautiful by day and enchanting by night? The Michigan Avenue Bridge, which is now the DuSable Bridge.

*Were you wondering about John Kinzie’s title as Chicago’s First Murderer? He also lays legitimate claim to First Clout. This is as good a place as any to explain:

In 1810, Kinzie wielded the First Clout, according to Chicago historian Dominic Pacyga. “Clout” is a distinctly Chicago term. As iconic 20th century Chicago newspaper columnist Mike Royko noted, the dictionary defines “clout” as a physical blow. In Chicago, he wrote, “Clout means influence—usually political—with somebody who can do you some good.”

Kinzie the fur trader also traded alcohol with the local Indians, a practice frowned upon by Captain John Whistler, first commander of Fort Dearborn. Kinzie pulled some strings with the powerful American Fur Company, got the troublesome Captain Whistler transferred, and a new set of commanding officers at Fort Dearborn.

Then in 1812, Kinzie killed Jean La Lime in a fight outside Fort Dearborn. Kinzie literally brought a knife to a gunfight, as he wielded a butcher knife to La Lime’s pistol—but for Kinzie, it worked. La Lime managed to shoot Kinzie in the shoulder, but still got the worst of it himself, and died of his wounds. Kinzie ran off, briefly abandoning his family and property. But Kinzie was able to return after the fight was ruled self-defense by an investigation. Who ran the investigation? The new authorities installed at Fort Dearborn after Kinzie got Captain Whistler transferred. So Kinzie gets the title of Second Clout, too.

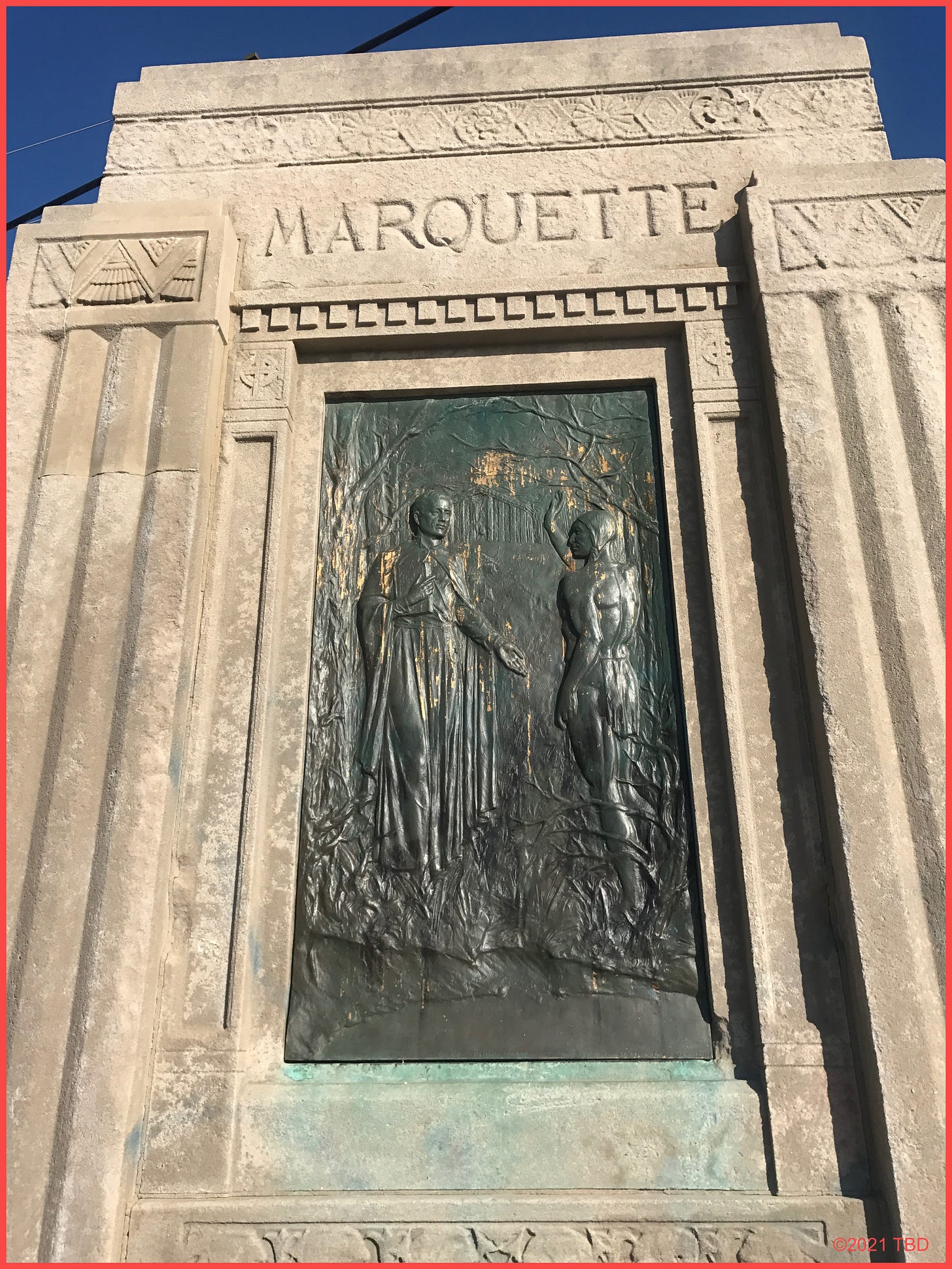

The Wrigley Building, Father Marquette and Louis Joliet

Did you know the Wrigley Building site is also the spot where French Jesuit priest Father Jacques Marquette and French explorer Louis Joliet first pulled their canoes onto land in Chicago in 1673, as they journeyed back north after their historic trip down the Mississippi? And the Marquette-Joliet party even built a cabin on the site, making it “Chicago’s first home to be inhabited by white men” as the Tribune put it in 1923?

Just kidding! There is no basis whatsoever for this city-wide mass delusion.

Marquette and Joliet set off in search of the Mississippi from the St. Frances Xavier Jesuit mission on the shore of Lake Michigan in Green Bay, Wisconsin. This was before Green Bay had any Packers, or cheeseheads to cheer them on. It is still ironic, given football’s epic Chicago-Green Bay rivalry, to think Chicago was ever thought to have been “discovered” by some guys from Green Bay.

Marquette and Joliet paddled down the Fox River, then the Wisconsin River, finally reaching the Mississippi. Coming back was trickier, against the current. So on their return trip to Green Bay, Marquette and Joliet left the Mississippi much sooner, following a shortcut to Lake Michigan recommended by friendly Native Americans. The shortcut took them up the Illinois River. Farther along, some more friendly Native Americans directed them up the Des Plaines River to a place where they could port their canoes a short distance to the banks of what we now call the South Branch of the Chicago River.

If we knew the precise spot where Marquette and Joliet stopped on the bank of the South Branch before slipping their canoes into the water to continue their journey, we might consider that bit of ground their first step in future Chicago. We don’t know the precise spot. For some context, here is the South Branch today on the bridge over Damen Avenue, looking east. As you can see, it is a far cry from the Wrigley Building.

After Marquette and Joliet slipped their canoes into the South Branch, they paddled up the Chicago River and out onto Lake Michigan. They did not stop at the future 400 N. Michigan Avenue and build a cabin.

Father Marquette spent the winter in Green Bay at the St. Xavier mission, and returned in 1674. This time, he headed directly to the Chicago River’s mouth on Lake Michigan. His party arrived there on December 4. They camped long enough to hunt for some food, then headed downstream on the South Branch another six miles, to a spot now typically identified as Damen Avenue, the site pictured above. Father Marquette fell ill, and they spent several months there in “a makeshift cabin” according to Miller’s City of the Century.

Here are some shots of the commemorative marker to Father Marquette erected nearby in 1930 under the reign of Mayor Big Bill Thompson. The area and the marker are no longer, um, pristine.

Nothwithstanding the fact that Marquette and Joliet did not even step foot on the riverbank near the Wrigley Building, Chicago giddily celebrated the imagined 250th anniversary of Father Marquette and Louis Joliet building the “first home to be inhabited by white men” on that spot—and they celebrated it not once, but twice.

In 1923, in honor of Marquette and Joliet’s arrival 250 years earlier, the city held a noontime ceremony. Students from every Chicago school, led by Mayor William Dever’s wife, gathered on the Michigan Avenue Bridge to throw flowers in the river. A schoolgirl named Kathleen Leo, identified as “girl athletic champion of America,” started things off by tossing the first bouquet into the river from the Wrigley Building tower.

A year later, Chicagoans hijacked President Calvin Coolidge into joining Mayor Dever at the Wrigley Building to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Father Marquette’s return to “the place where he built his hut 250 years ago”. A priest from Chicago’s Loyola University got in a canoe dressed up as Father Marquette, along with somebody dressed up as an Indian in a huge feathered headdress, and they paddled up to the Wrigley Building. Mayor Dever and President Coolidge greeted them next to a replica of the house that everyone pretended Father Marquette had built on that precise spot. Again, just to be clear, the whole thing never happened. Sounds like everyone had a good time in 1924, though.

In 1957, Loyola University put three students dressed as Father Marquette, Louis Joliet and an Indian guide in a yellow canoe on the Illinois River near Morris, IL to recreate the trip for the Jesuit’s centennial year in Chicago. Three days later, the explorers pulled up to a landing next to the Wrigley Building and shook hands with Mayor Richard J. Daley in a light rain as boat whistles blew and a crowd watched from the Michigan Avenue Bridge.

“I wouldn’t go through it again for $1,000,” said the student who played the Indian guide.

The Wrigley Building and Roseland

Roseland is so, so far away from the Chicago’s Magnificent Mile. You almost literally can’t get any farther and stay in the city. But yes, there is a Roseland connection, so it’s only fitting to close with it.

Only a year and a half after the south tower opened in 1921, it was the Wrigley Building’s name that instantly sprang to the lips of 9th Ward Alderman Sheldon Govier of Roseland when he needed to invoke an iconic Chicago skyscraper.

It was during a City Council police committee meeting about police brutality. The only thing more authentically Chicago than skyscrapers is investigations into police brutality and corruption. It’s a shame the best police scandals don’t get landmarked too, because they are every bit as interesting as the city’s architecture.

Ald. Govier, who hailed from and represented Roseland, was a true man of the people. That meant he got in a lot of scrapes himself, and he was tired of getting pushed around by cops. More on Ald. Govier in Chapter 5: Roseland and Hyde Park.

One day in 1921 while the City Council police committee was investigating police brutality, they physically examined one Edmund Fitch—who’d been arrested for allegedly possessing a stolen car. Fitch claimed he’d been beaten with a rubber hose by a police detective. Get this: The aldermen took Fitch into a private meeting room and had him disrobe.

Fitch’s injuries included “contusions on both temples” and “a series of welts across his back” dramatic enough to make the aldermen, who in those days were all men of the people and not a bunch of lawyers, gasp.

The aldermen sent for Chicago Police Chief Charles Fitzmorris, who didn’t show up. Next they sent for Capt. John Naughton, head of the police department’s automobile detail. For some reason, Naughton heeded the call.

Naughton claimed that Mr. Fitch had told police that he got hurt by falling off a bench.

“He couldn’t have got all those bangs if he had fallen off the Wrigley Building,” retorted Ald. Govier.

“We ought to find the copper that did that and beat him up with a piece of lead pipe,” suggested another alderman.

Admittedly that last line has nothing to do with the Wrigley Building.

NEXT in Chapter 2 Notes: Trump Tower. Remember, they used to slaughter hogs there.

SUBSCRIBE

If you’re not immediately repelled, why not subscribe? You’ll receive a new chapter of “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” every month in your email box, along with a weekly compilation of the daily items on social media: THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, and MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY.

And why not SHARE?

Maybe you know someone else who would enjoy reading about a ten-year-old Italian-American kid on the South Side of Chicago in 1972. Didn’t your parents teach you to share?

Oh boy, this could be another rabbit hole.

Don't forget, there was a time the Sun-Times docked a boat on the river, next to their building, for months at a time to store newsprint.