Chapter Two Notes, Part 2: Architectural Thunderdome on the North Bank, Marina City v. the IBM Building

Not your father's footnotes. Fun.

FYI, if you’re not a regular reader: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” is a hybrid novel/1972 Chicago primer, posting one novel chapter per month. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972. Each chapter comes with fun Notes on key topics that pop up as our story progresses. Lots of pictures! Chapter 2 begins by following the sun’s rays poking west down the Chicago River at dawn—crossing the Michigan Avenue/Du Sable Bridge and passing over the Wrigley Building, Trump Tower, the IBM Building, and Marina City. Then the focus of our story, Steve Bertolucci, arrives at work at the IBM Building.

So Notes Part 1 covers the Wrigley Building and Trump Tower, here. Part 2 below covers the IBM Building and Marina City and their eternal struggle on the north bank of the Chicago River. Find out what the novel is all about here.

The IBM Building

Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe is always called “Mies” as if he were the Cher of modern architecture, which he kind of is. The 52-story IBM Building where Steve Bertolucci works is Mies’ last highrise design—he died during construction.

Steve is the focus of this site’s main feature, “Roseland, Chicago: 1972.” He works on the 14th floor of the IBM Building at the accounting firm of Rose & Rose. Now back to the IBM Building.

A native German, Mies came to Chicago in 1936 to direct the School of Architecture at the South Side’s Armour Institute of Technology, which soon became the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). Sorry Germany, but since Mies went on a creative spree designing the archetypal buildings of architecture’s Modern Movement after he arrived in Chicago, Chicago claims him.

Which is a double-edged sword. Many people hate Miesian steel & glass box skyscrapers, and Mies is now almost synonymous with Chicago. Plenty of Chicagoans include ourselves among the glass-box haters, but we perversely claim Mies anyway, because we like to think everything started here. At least don’t let New York have Mies. New York already got his most acclaimed work, the Seagram Building. Many feel the IBM Building, like Chicago, is not far behind.

Mid-20th century Chicago was soon full of Miesian steel towers, between Mies’s own work and the buildings put up by his former pupils and imitators. There’s the Equitable Building, due east of the Wrigley Building across Michigan Avenue. Or the Daley Center, across from City Hall. Novel readers, remember the gigantic Picasso that Steve’s boss Sol hates so much? It looms over the Daley Center Plaza. Try the quiz below. Which is which? Architects and architectural buffs can tell them apart, but can you? Answers at the end. No peeking.

Architects, critics and buffs can be quite snobby about the ordinary Chicagoans who don’t share their admiration for Mies van der Rohe. And Steve and Sol are very ordinary Chicagoans. They harbor no affection for Miesian modern architecture, including the IBM Building in which they work. How they love looking out the floor-to-ceiling IBM Building windows at Marina City across State Street, imagining how wonderful life would be in a round building. It’s always better across the street, right?

But even if you hate steel & glass boxes, when you hear people who love the IBM Building talk about it, you begin to look at that building, and all buildings, differently. Chicagoans have been blessed over the years to read so many top-notch architecture critics/writers in our multiple newspapers and later websites—people who could make us see things in a new way. A necessarily partial list: The Daily News’ M.W. Newman, the Sun-Times’ Rob Cuscaden and Lee Bey, the Tribune’s Paul Gapp and Blair Kamin, and Lynn Becker in many outlets but especially in the Reader. Please click on comments at the end and let me know who should be added to that list, and I’ll quickly amend-or tweet to @RoselandChi1972.

To my knowledge, as our newspapers wither away, there are no paid full-time architecture critics left here—though luckily Crain’s Chicago Business real estate writer Dennis Rodkin works a lot of architecture into his beat, bravo! The internet of course is partially to blame for the death of newspapers, but ironically, that’s where we count on getting our architecture fix now. The problem is, you have to seek out architecture writing now. It doesn’t show up while you drink coffee and page through the newspaper, tugging on your sleeve and making you look at something you never noticed before. So ordinary Chicagoans, like Steve and Sol, miss most of it. But back to the IBM Building.

On his website, Chicago architecture critic Lynn Becker notes that the IBM Building is set on its own hill, “like the Acropolis.” Mies “liked to put his buildings on a plinth,” Becker writes, though in the IBM Building’s case, the plinth/hill is “dictated by the strange surface conditions of downtown Chicago, where much of the city was raised up out of the muck over a century ago.”

The IBM Building’s 26-foot-high glass-walled lobby does have a soaring, cathedral feel that even the most ardent hater of modern architecture has to appreciate it. As Becker puts it, “the effect of that open, clear lobby is to ‘dematerialize’ the building. The curtain wall stops at the lobby's ceiling. The outer columns descend to the ground, forming an open arcade around the recessed, glass-enclosed lobby. At night, the dark tower seems to float above a pillow of light.” It really is quite beautiful.

Becker also thinks Mies has bested beloved earlier Chicago architect Louis Sullivan, who believed a skyscraper “must be every inch a proud and soaring thing, rising in sheer exaltation that from bottom to top it is a unit without a single dissenting line”.

I can see that, now. Maybe you prefer a spare Norfolk Pine over a thick Blue Spruce, for instance. I still prefer the thick spruce—but I don’t mind seeing some Norfolk pines too. I just hate to see the skinny pine trees crowd out all the spruces, which seemed to be happening in the architectural forest for a while there.

If you’ve read Chapter 2, you know that Steve comes to work at the IBM Building from his home in the South Side’s Hyde Park neighborhood on the Metra Electric (formerly the Illinois Central). He debarks at Randolph and walks north up State Street to Wacker Drive and the Chicago River. It’s closer, but Steve doesn’t walk up Wabash anymore because he doesn’t like the giant letters on Trump Tower advancing at him so early in the day. So Steve crosses the Chicago River on the State Street Bridge. Once across, he’s arrived on the southwestern edge of the IBM Building’s riverside plaza.

Now Steve steers diagonally northeast across the plaza to the revolving doors on Wabash. His head tends to be down at this point, his briefcase brushing the side of his suit. The Sun-Times he read on the train will be tucked under one arm, and a Tribune will be inside the briefcase for later, when he has room to spread out.

At this point, Steve’s eyes are usually fixed on the dull pink-black-grey speckled granite tiles paving the plaza. He’s thinking about the clients he needs to call.

Once Steve pushes through the revolving doors, he passes a bust of Mies van der Rohe by sculptor Marino Marini. If he’s preoccupied and his eyes are still down, the most primal part of Steve’s brain, the part that still thinks it’s on an African savannah where a prowling lion might be hiding in the high grass, will register Mies’ bust as a conscious entity, even though Steve knows Mies is a sculpture. He sometimes gives a slight start as he passes Mies.

As Steve walks briskly across the IBM Building lobby toward the elevators, covered in a subtle Travertine marble, he’ll definitely look down because he loves the shiny, polished pink-black-grey speckled granite floor. It’s the same granite as the plaza outside, a continuous plain of it, giving you the feeling the building was wholly constructed elsewhere without a floor and then plunked down here. A little trick Mies van der Rohe liked to use, integrating the building with its environment.

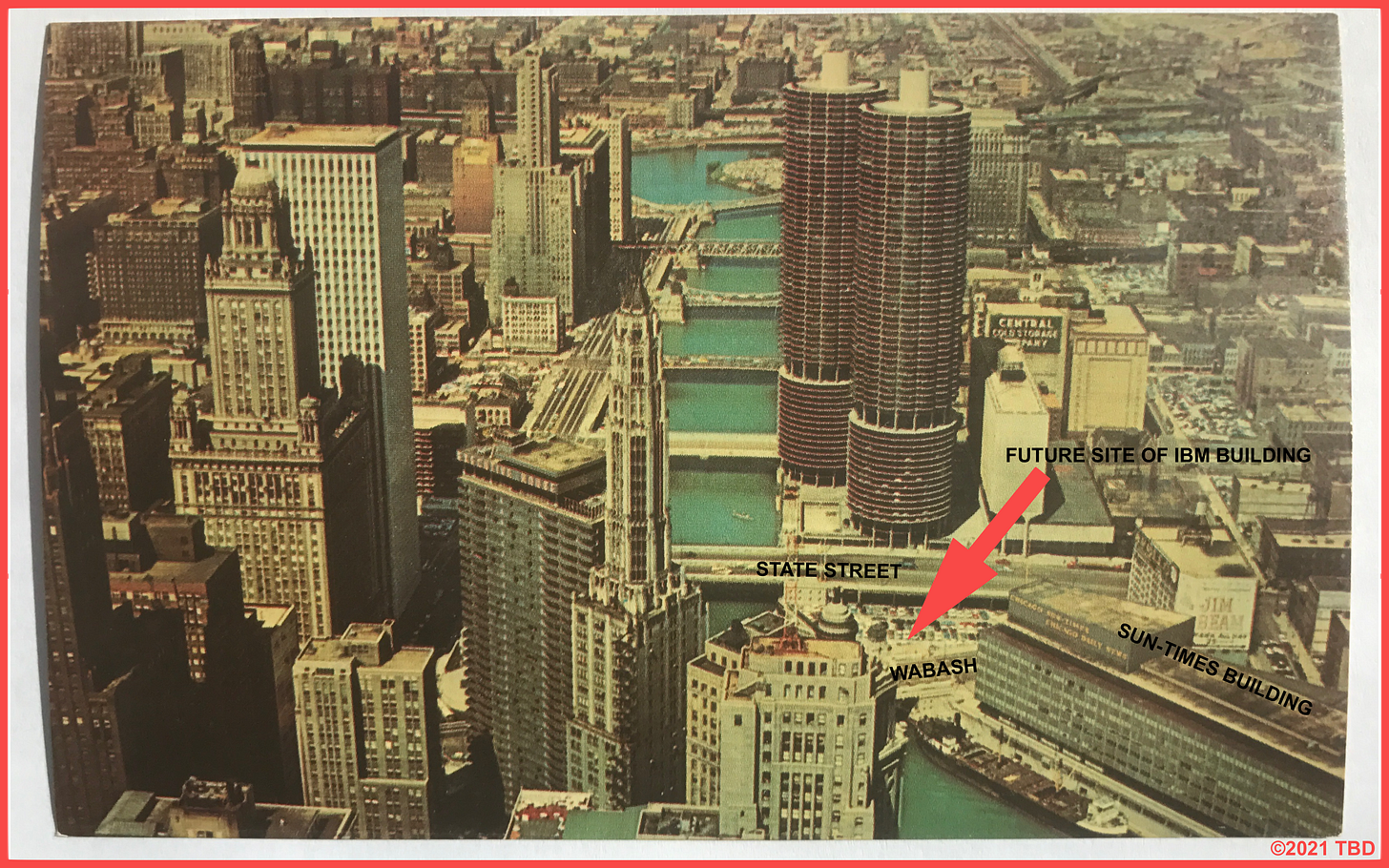

The amazing thing about the IBM Building, really, is that they wiggled it into the site at all. Let’s look at that old curled postcard from Chapter Two one more time, to make sure we appreciate the feat.

The big red arrow points to the site where the IBM Building will rise, wedged in between State Street to the west (toward the background) and an angled stretch of Wabash to the east (foreground). And let’s not forget there’s a major river on the south end, which will not be forgiving of any mistakes. In this postcard, the site is still a parking lot. It’s sometime between 1964, when Marina City was finished except its theater, and 1969, when the IBM Building construction began. The Sun-Times Building, in the lower right corner, is still new, having been finished in 1957—it’s the future site, recall, of Trump Tower.

You can see that’s a lot to deal with. But in addition, you can’t see that below the parking lot covering the site, the Sun-Times retains the right to store giant rolls of newsprint it uses to print its newspaper inside its own building across the street. Each roll was about the size of a Prius. And Mies also has to design the IBM Building’s base around the underground railroad tracks that enable delivery of the giant rolls of newsprint—which is why the IBM Building has two sets of elevators, with the foundations of the elevator cores straddling the tracks below.

Imagine the day in 1966 when an aide pushed 80-year-old Mies van der Rohe in a wheelchair up to that oddly shaped sliver of land, so the famed architect could inspect the site for what would become his last highrise. Mies looked around. “Where’s the site?” he demanded.

Mies Van der Rohe died in 1969, before the building was finished. The IBM company abandoned its namesake building in 2005. Three years later, Chicago made the IBM Building a city landmark, the youngest building ever to gain that distinction. For those who don’t know any better, the building is now known by its address—330 N. Wabash. By 2013, a team headed by Mies’ grandson, architect Dirk Lohan, had redesigned the bottom 13 stories into the Langham Hotel Chicago.

Every weekday morning, the bust of Mies in the IBM Building lobby watches security guard Michael O’Hare as he greets the morning sun, and sometimes scares Steve Bertolucci as he walks through the revolving doors on Wabash.

Architect, Mies van der Rohe/Office of Mies van der Rohe, and Associate Architect, Engineers C.F. Murphy Associates, 1971; 330 N. Wabash

For a deeper look at Mies’ architecture, see Lynn Becker’s website for a collection of Mies articles, particularly “Apotheosis of the Skyscraper: The Rise of Mies van der Rohe’s IBM Building.” Also, check out the city of Chicago’s Landmark Designation Report. Don't be scared off by the title—it has a lot of pictures.

Marina City

Round Marina City faces down the resolutely rectangular IBM Building across State Street, two implacable architectural foes in an eternal urban stand-off, or as eternal as reinforced concrete, glass and steel prove to be.

Marina City architect Bertrand Goldberg referred to Miesian steel-and-glass box highrises like the IBM Building as “psychological slums.” But Goldberg also worked in Mies van der Rohe’s German office and studied at the famous Bauhas. When the Art Institute of Chicago conceived a sweeping Bertrand Goldberg exhibition in 2011, it was Mies they named as Goldberg’s mentor. Now Goldberg’s most iconic creation squares off with Mies’s last highrise.

Since Chicago is often seen as a city built by railroads, it’s fitting that such an icon of Chicago as Marina City is built on land that was owned for a century by the Chicago Northwestern railroad. Before that, the first official owner of the land was the federal government’s Chicago “Indian agent,” Alexander Wolcott, who lived there in a modest cabin.

Marina City was the first highrise apartment building built in downtown Chicago, and arguably the first anywhere to combine homes, stores, offices and entertainment into one complex. And they did it in the early ‘60s, right smack when thousands of Chicagoans were driving to the suburbs as fast as they could on brand new expressways. This was thanks to Goldberg, and a human triangle of power and clout. They all bet that Marina City could draw hundreds of Chicagoans back downtown like bees to honey, an apt metaphor because Goldberg imagined each Marina Tower as a stack of flower petals.

As Pulitzer Prize-winning former Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin wrote in his 1997 obituary for Goldberg, his “significance transcended architecture. In the 1950s, when there was widespread pessimism about the future of cities as places to live, Mr. Goldberg posed a vital alternative with the five-building Marina City complex”.

The human triangle of power and clout that helped Goldberg create Marina City consisted of Mayor Richard J. Daley, who needs no further explanation since his name is a synonym for clout; William McFetridge, then head of the Building Service Employees International Union, better known as the Janitor’s Union; and Charles Swibel, crony of Mayor Daley, and a real estate sharpie whose name should have been invented by Charles Dickens. It was Swibel who hit upon the novel idea of leveraging the Janitor’s Union pension funds to build highrise apartments that the janitors could not afford to live in.

The genesis of Marina City raised eyebrows for years, even in Chicago. As legendary Chicago newspaper columnist Mike Royko wrote in his biography of Mayor Daley, Boss, “His (Mayor Daley’s) good friend Charlie built it, with financing from the Janitor’s Union, run by his good friend William McFetridge. For Charlie Swibel, building the apartment towers was coming a long way from being a flophouse and slum operator.”

Marina City was aggressively marketed as a modern, progressive and integrated complex—about 25% of the Janitors’ Union members were African-American. But in 1964 the union, under a new president, decided it didn’t need to have its money in a development where no janitors of any color could afford to live. Swibel’s company bought them out. Rents went up right after Marina City opened. No janitors ever moved into Marina City, and there weren’t many African-Americans either—just six apartments out of 896, according to a 1964 Ebony magazine feature.

Marina City instantly became the face of modern, cool Chicago, the quintessential “City-within-a-City” as Goldberg called it, housing everything from a theater and bowling alley to restaurants and dry cleaners. Again, that had never been done before.

The towers were the tallest reinforced concrete structures in the world when they opened for residents in 1963. They were so revolutionary at the time, many Chicagoans were literally afraid the towers would fall into the river. As the complex opened, acclaimed Chicago Daily News writer M.W. Newman noted that when you take a picture of Marina Towers together, they seem to lean—and that many people thought they really did.

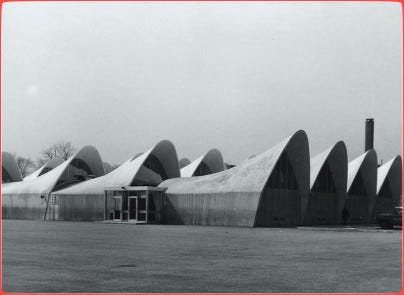

But that’s not as silly as it sounds. As Chicagoans watched Marina City going up, they also watched city newspapers write stories about the collapse of a section of the shell-shaped concrete classroom roofs at the Brennemann public school under construction at 4239 N. Clarendon—designed by Goldberg, and made out of the relatively new technique of sprayed-on concrete over reinforced steel bars, with no forms. Marina City was reinforced concrete and “the first major use of slip-form construction,” as Chicago’s Landmarks report on the building describes it. Most Chicagoans, not being construction experts, could be forgiven for not understanding the difference.

Headlines and recriminations over the Brennemann roof collapse flew for two years as Marina City rose on the north bank. The contractor blamed Goldberg’s design, while a school board report thought perhaps some forms should have been used as the sprayed concrete cured. Chicago’s school superintendent eventually declared it a matter for the courts to decide and hired Goldberg to build another school.

Brennemann’s 24 concrete vaulted classroom roofs were finally declared safe by the city’s building department in mid-1963, as Marina City filled with new tenants. The school opened in 1964. But what would you think, if you knew a fancy schmancy new concrete roof at the Brennemann school had collapsed, and then you stood on Wacker Drive and looked up at those two crazy round concrete towers going up across the river—apparently leaning toward each other? *

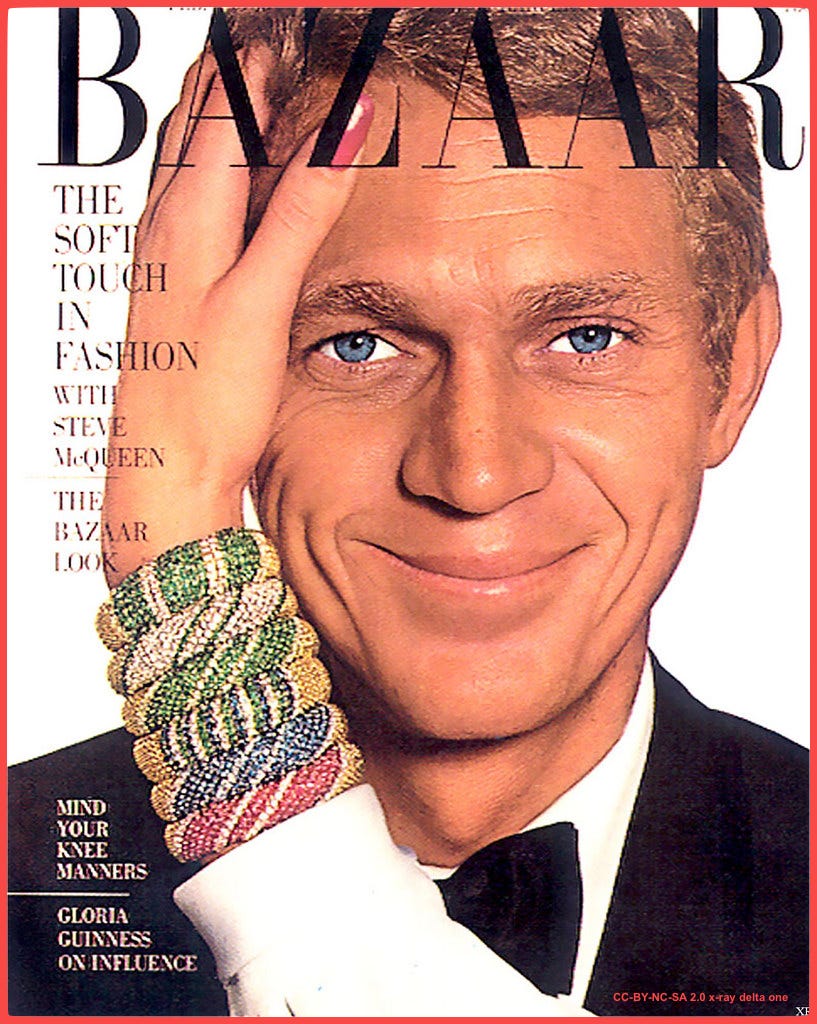

The only thing that could make Marina City more cool was Steve McQueen, who obliged in 1980 when he starred in The Hunter. Steve McQueen, driving a red tow truck and mugging for the camera throughout, chases a criminal in an ugly green car up the winding parking garage ramp of the eastern tower. He finally forces the criminal to drive the ugly green car straight off the edge of the uppermost parking garage floor, plunging in a rapturous arc into the Chicago River below.

Watch the famous Marina City car chase on YouTube here. I have to say one of the things I love best about Chicago is the fact that they let them do this absolutely insane stunt. No special effects. No computers involved whatsoever.

As mentioned in Chapter Two, when Marina City was still new in the ‘60s, Steve and his older brothers knew it would be the coolest place in the world to live—a round building!—even though their Nonna said she’d never live stacked up in the air with the neighbors’ asses in her face. Here is a snapshot taken from Randolph and State by Steve’s older brother Frank in 1969 during a 5th grade school field trip. It’s my favorite picture of Marina City, even though you only see half:

Cool as Marina City was, Chicago native son Bertrand Goldberg was no elitist—quite the opposite. As the Art Institute pointed out in its exhibit notes, Goldberg “received national recognition in the 1960s as a humanist architect and thinker”. He thought and wrote about architecture’s role in public education, health and housing, and he believed in “democracy through architecture”.

“With his rumpled hair and simmering eyes, his tweed jackets and stylish shirts, and his courtly, genteel air—now impish, now prickly—Mr. Goldberg often seemed more of a poet than an architect,” wrote Blair Kamin in his obituary of Goldberg. “He was once described as a humanist whose medium happened to be architecture.”

Even as Marina City was taking shape, Goldberg designed Hilliard Homes for the Chicago Housing Authority, due south of Marina City and not far outside the Loop at State Street and Cermak (22nd Street). There, Goldberg did the seemingly impossible: He created highrise public housing that was beautifully and humanely designed to become a true community. The four towers even resemble Marina City, then and still a symbol of affluent city living.

As Goldberg put it later in an Art Institute of Chicago’s oral history interview, “we simply weren’t storing people”. Hilliard remained a safe, welcoming project until about the 1980s, when the CHA stopped maintaining the property and screening residents rigorously. In 1999, CHA brought in a private development management company, which rehabbed Hilliard extensively and reopened it to rave reviews in 2006—still as housing for CHA and low-income residents.

* Re the Brennemann School and the leaning Marina Towers: Marina City’s two towers stayed upright. The classroom roofs at the Brennemann school were not as successful. Less than ten years later, parents bitterly complained the place was “almost falling apart” with leaky roofs, leaky walls, and falling plaster. The official Bertrand Goldberg website tactfully notes that due to Chicago’s climate, “the building was subject to leaking due to expansion and contraction of the roof structure. The entire roof structure has since been covered over.” I took a picture, but you’d never recognize it. Too bad—leaky as they were, those 24 sloping, shell-shaped concrete roofs looked really cool.

Architect, Bertrand Goldberg Associates, 1960-1967; 300 N. State Street

UP NEXT: Chapter 2 Notes, Part 3: The final installment, everything else after the rising sun crosses all the buildings we have now examined. That includes stuff like Jesus Christ Superstar, crazy cigarette advertising, paczkis, Vince Lombardi and Papa Bear George Halas. See the Chapter Notes Contents page for earlier installments and Optional History Chapters.

SUBSCRIBE

If you’re not immediately repelled, why not subscribe? You’ll receive a new chapter of “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” every month in your email box, along with a weekly compilation of the daily items on social media: THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972, and MIKE ROYKO 50 YEARS AGO TODAY.

And why not SHARE?

Maybe you know someone else who would enjoy reading about a ten-year-old Italian-American kid on the South Side of Chicago in 1972. Didn’t your parents teach you to share?

We’d love to hear from you.

15