To access all site contents, click HERE.

Mayor Brandon Johnson, like any good comedian, delivers his best lines with a straight face.

And he was getting them off to perfection as he took part in the unveiling ceremony on April 24 for the proposed Bears domed stadium on the lakefront between Soldier Field and McCormick Place.

“This plan not only envisions a new domed stadium but it reimagines the entire museum campus in a way that truly aligns with the historic Burnham plan,” Johnson boomed, gaining steam as he went. “It was Daniel Burnham’s vision for the lakefront was to center it around people, the people of Chicago. He envisioned an active lakefront with space and amusement for everyone to enjoy. The plan revitalizes that vision and today’s plan imagines, invigorates new parks with public sports fields, field house facilities for everyone, but especially our young people in this city, the result of a lakefront, new green space, that will be available to all residents. It gives us an opportunity to enjoy this campus in a far more collaborative way…This plan truly embodies the spirit of the Burnham Plan….Simply put, this is going to reinvigorate the entire city of Chicago. It WILL be the crown jewel of the city of Chicago.”*

He actually said that, and nobody laughed. In fact, the Bears executives and city flacks beat their palms together.

*Verbatim, which is why it may differ slightly from quotes you read elsewhere.

See what I did there? Regular readers of Mike Royko 50+ Years Ago Today know where I’m going with this: Except for Mayor Johnson’s quote, those are Mike’s words, written about Mayor Richard J. Daley for the Chicago Daily News on April 26, 1972 and repurposed here for our current civic challenge.

Normally we focus on 20th century politics in this space, but the present just stuck its foot in the door and refuses to go away. I mean, who figured Brandon Johnson would turn into Richard Joseph Daley?

Today, the “J” stands for “Johnson”—Brandon Johnson.

“Maybe someday he’ll build a big superstadium for all the teams, better than any other city’s,” Mike wrote in the masterful first chapter of Boss. “Maybe on the Lake Front. Let the conservationists moan. It will be good for business, drawing conventioneers from hotels, and near an expressway so people in the suburbs can drive in. With lots of parking space for them, and bright lights so they can walk.”

But who is “he”? Mayor Richard Joseph Daley, or Mayor Richard Johnson Daley? Because as we’ll see, Brandon Johnson’s lakefront plan is really just a predictable update of Daley’s lakefront stadium plan from 1971. And as long as a single Chicago bungalow-sized lot remains vacant on the lakefront, the proposals will keep coming.

Let’s review Mike’s stadium prediction in Boss to compare RJD 1971 and RJD 2024.

Lake Front.

Moaning conservationists.

Cheering businesses that will benefit.

And a complete makeover of DuSable Lake Shore Drive at the Museum Campus that will screw South Siders trying to drive downtown through its construction for years.

Check, check, check and check.

More on Mayor Daley’s lakefront stadium version further on. Today’s Bears/Johnson plan has all the key elements, as we'll see. I just hope Mayor Richard Johnson Daley isn’t dusting off the Crosstown Expressway too.

The Bears and Mayor Johnson want to take the lakefront between the Field Museum and McCormick Place and stuff it with a colossal domed stadium, a new two-story parking garage, and eventually a hotel and restaurants and another museum and a skating rink and God knows what all. Watching the Bears’ elaborately produced promotional video, I lost track at some point. There were just so many AI-generated families picnicking, AI-generated adults shopping at farmer’s markets, and AI-generated kids playing soccer.

Can you imagine having to drive your kid downtown and pay for parking, all for a five-year-old’s soccer game? Or to buy fruit? Me either. It’s bad enough when you’re the one who has to bring the orange slices. On the other hand, maybe some weeks there could be a farmer’s market at the same time as your kid’s game, and you could get the oranges before the first kick-off. Cross your fingers.

Want to see the whole Bears fantasy film? Here it is:

Funny thing about those AI people cavorting at the fabulous Bears stadium campus, though. None of them were carrying stacks of money to pay up to $100,000 for a personal seat license, though Crain’s Chicago Business* reported that could be the top rate for the best season ticket seats. Maybe the seat licenses and the parking fees are offset by the really good prices at that farmer’s market. I assume we’re going to get something for our $6.9 billion.**

*Reported by Justin Laurence and Danny Ecker

**As Fran Spielman and Mitchell Armentrout reported in the Sun-Times, Illinois Sports Facilities Authority executive director Frank Bilecki says Chicago and Illinois taxpayers will end up forking over $6.9 billion for the proposed Bears stadium when you factor in servicing 40 years of debt plus the money we still owe for renovating Soldier Field and Guaranteed Rate Field. We’re such easy marks. It’s amazing any of us get home with our wallets.

In all fairness we should add, since Mayor Johnson repeated this number roughly 20,000 times at the presentation, that the behemoth stadium-parking garage-hotel-museum-restaurants-skating rink-blah-blah-blah plan will feature 20% more green space than today’s museum campus. Mayor Richard Joseph Daley claimed his plan would reduce the stadium-parking footprint by 65%, but he intended to tear down Soldier Field completely. Mayor Richard Johnson Daley would just demolish the historic original stadium and the grotesque 2003 addition, but leave the colonnades surrounding an open field.

The open field is where the farmer’s markets and the soccer games are going to be, along with all the real, not AI-generated people who don’t have thousands of dollars to blow on personal seat licenses and season tickets. You didn’t think you’d get inside that domed stadium for free, did you?

As I listened to Mayor Johnson’s pitch, I kept thinking it reminded me of something. Pretty soon I remembered Mike’s April 26, 1972 column, with which we opened this post. He wrote it almost exactly 52 years ago to the day.

Mike was writing about Mayor Daley’s speech at the ground-breaking for the 36-story Hyatt Regency Chicago Hotel.

Here’s the Hyatt today at 151 E. Wacker.

Mike described the new hotel’s location as “Wacker Dr. east of Michigan Av.” Back then, they were still waiting for Wacker Drive to catch up with the development of the Illinois Central Railroad yards between Michigan Avenue and the lake, and from Randolph to the river. Today’s monolithic slab of nonstop high-rises still looked mostly like the postcard below.

In 1972, the only additions to this scene were along the borders—Illinois Center, towers One (finished) and Two (still under construction), just east of Michigan Avenue; and the Standard Oil Building (now Aon Center) next to the Prudential Building on Randolph. The red arrow points to the Hyatt’s future home.

As the Chicago Architecture Center notes, the first structure on this site was Fort Dearborn, which gave way to the IC rail yards by the mid 1800s. (See The Mighty IC for a rollicking ride through the history of Chicago’s most important railroad.) Then in 1966, the Illinois Supreme Court handed the IC the air rights for their grimy property. The race was on to fill it up. Mayor Daley called it the “greatest real estate deal in history.” No molecule of sky left behind.

As the IC grew rich building Illinois Center in 1972, the railroad was also gearing up to develop its other golden goose—the air rights above its rail yards at the south end of Grant Park abutting Lake Shore Drive. We know those rail yards today as Central Station, named for the original Illinois Central Station that operated there on 12th Street/Roosevelt Road until 1972.

Not everybody in 1972 thought it was such a great idea to slap back-to-back high-rises on every empty inch of land left between Chicagoans and the lake. A few weeks after Mike’s Hyatt column, leaders of the Citizens Action Program, a prominent grassroots organization of the time, demanded that the city open the private meetings it had been conducting with the IC as they planned development of the south train yards. The CAP people mentioned a little thing called the 1967 Open Meetings Act.

CAP had the quaint idea that it’s wrong for the city to secretly negotiate deals with private companies that will affect the entire city for decades to come. I assume they would have felt the same way about secret meetings to plan a lakefront stadium.

“We fear this land will turn into a high-rise city within a city, open only to those who can afford it, and the lakefront will be eaten up,” CAP leader Paul Booth told the Tribune’s Cornelia Honchar.

So that was the general scene as Mike Royko wrote about Mayor Daley’s speech at the Hyatt Regency Chicago groundbreaking:

“He shared some of his thoughts about the past and the future of the city’s lakefront. On the past, he boasted: ‘No one has defaced our lakefront.’”

That’s the line Mike thought everybody should have laughed at, a direct retort from Mayor Daley to a then-recent comment from Ald. Leon Despres (5th) during a City Council hearing we’re about to get into. Mike thought it was funny because he remembered the trees that had recently come down in Jackson Park for extra roads, not to mention McCormick Place.

Younger Chicagoans, did you know the lakefront at 22nd Street used to be available for all kinds of public uses, rather than blockaded by a convention hall that annually kills hundreds of birds migrating along the shore? The Stevenson feeder ramp launching cars onto DuSable Lake Shore Drive, similarly, is not a natural part of the landscape. McCormick Place and the Stevenson ramp always looked as inevitable to me as a mountain in the Rockies, because like our Younger Readers, I’ve never known it any other way. Those who ever saw the lake at 22nd Street from Lake Shore Drive are few now. But that scene is not natural. Choices were made to put both monoliths right where they are now, with the familiar argument that nobody was doing anything with the land anyway.

“A convention hall that could have been built almost anywhere now sprawls across acres of lakefront park land,” Mike wrote in that 4/26/72 column. “Parking lots have eaten up their share. A huge traffic interchange took its bite….Yet, he says, ‘no one has defaced our lakefront.’ The Normandy invasion left fewer scars on the coast of France.”

Mike didn’t forget Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago. But he did not say that McCormick Place or the Stevenson feeder ramp “aligned” with Burnham’s vision, one of Mayor Johnson’s favorite terms at the recent stadium presentation. Here’s Mike’s assessment:

“None of this was in the plan of Daniel Burnham, the great planner and visionary who drew up the design for the lakefront that would be for the people. But they are all there, and more, courtesy of Daley and his predecessors.”

To which I add: And his successors, if Mayor Richard Johnson Daley has his way.

“That thigh-slapper having been delivered,” Mike continued, “he went on to say: ‘Our plan for the future is to open up the lake to the people.’”

Check, yet again. I can’t tell you how many, many times Brandon Johnson described the stadium plan last week as something for the people. For example, one reporter asked if Johnson was prepared to spend city dollars on the likely lawsuit by Friends of the Parks.

“Yeah what we’re prepared to do is to continue to invest in people,” Johnson answered. “We’re prepared to put 23,000-24,000 people in the city of Chicago to work. You know my vision for the city of Chicago is very clear, particularly around environmental justice, in creating more open space, we do that, paying attention to the needs of our young people. As [Bears president] Kevin Warren has articulated, if you play a spring sport in Chicago you have a tough time having your game played if you play a fall sport, and I know because I have children who play spring sports, and this provides us with a very unique opportunity not just to grow our economy but to show our young people that we actually love them, care enough about them that we’re willing to invest in them.”

As for that likely lawsuit: We can only hope that the Friends of the Parks once again does the hard work of protecting Chicagoans from our own government. If so, they would probably oppose the Bears domed stadium—as they did the failed Lucas museum—based on the Lakefront Protection Ordinance.

The Lakefront Protection Ordinance prohibits new private construction east of Lake Shore Drive. But Mayor Johnson and Bears president Kevin Warren were quite confident, at the presentation, that their plan palms the Lakefront Protection Ordinance, stuffs it up a municipal sleeve, and finally deposits it in a deep city pocket where nobody will ever see it again. That’s because the stadium would be publicly owned.

Mayor Johnson and Bears president Kenneth Warren conjured up a real Penn and Teller trick right there—fooling everyone by constructing their plan to avoid the Lakefront Protection Ordinance, then explaining how they accomplished their sleight of hand. They just aren’t as funny.

But it figures that Chicagoans have to keep battling horrific lakefront monsters and the mayors who create them, because the Lakefront Protection Ordinance is not a crucifix we can hold up to fend off unholy schemes while chanting “Forever open, clear and free, forever open, clear and free!”

No, the Lakefront Protection Ordinance is itself a creature of that darkest of dark arts, Chicago politics. Knowing that will not help us fight off Mayor Johnson and the Bears—and now I’m hearing Winston Churchill in my head—

—but the ordinance’s impious origin story is rather interesting, and it also leads us to a terrific Mike Royko column about Mayor Daley’s 1971 lakefront stadium plan. So let’s take a look.

The Lakefront Protection Ordinance

The Chicago City Council passed the Lakefront Protection Ordinance, as we now call it, on October 24, 1973. The Council at that time was—as we all know—firmly under Mayor Daley’s control. Only a handful of noisy independent aldermen were around, strictly for entertainment purposes. (Just kidding Professor Simpson!)

By definition, the Lakefront Protection Ordinance could not have passed out of committee, much less passed in the Council, without Mayor Daley’s nod. So Mayor Daley wanted to stop lakefront development, right? Hmmm, not exactly.

The right question is, why did Mayor Daley bring forth the Lakefront Protection Ordinance and cause it to be passed?

For that, we can thank this man.

Hyde Park liberal Rep. Robert Mann served in the Illinois House for 16 years, starting in 1962 when the Machine’s 5th Ward Democratic organization slated him. Mann served with Abner Mikva and Paul Simon, who would go on to become famous Illinois political figures, and also Anthony Scariano, who regular readers may remember was a personal friend of Mike Royko’s. Together, they were known as the “Kosher Nostra” in Springfield.

But in 1971, Mayor Daley/the Machine threw Rep. Mann off the official Cook County Democratic ticket for the upcoming 1972 primary. They did not “slate” him, as the process is called. The Machine slated someone else, and bent all its power to getting that guy nominated to run in the general election instead.

Mann’s two worst sins: Opposing the Machine’s re-slating of Cook County State’s Attorney Ed Hanrahan, then under indictment for his office’s 1969 predawn police raid on a Black Panthers apartment during which Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were killed…

…and sponsoring the Lake Michigan Bill of Rights in the Illinois legislature.

It’s the lake that got Mann bounced out of the Machine.

“I’m not ready to be read out of the Democratic Party,” a defiant Mann told an Izaak Walton League group meeting at the Adventurer’s Club at 120 S. Michigan. “If being for the protection of the lakefront makes me a poor Democrat, then I plead guilty.”

Mann won his primary anyway, and later in April 1972 he testified at a City Council Environmental Control Committee hearing. The aldermen were taking testimony about a lakefront plan that Mayor Daley would soon release, accompanied by city legislation to rule lakefront development. This was the initial conception of the Lakefront Protection Ordinance, only slightly less scary than Rosemary’s Baby—a Mayor Daley baby born to kill Rep. Mann’s Bill of Rights in its cradle. Mayor Daley’s lakefront construction plans had been quietly percolating behind the scenes for some time as Rep. Mann worked on the lake Bill of Rights in Springfield. As Rep. Mann had complained to the Izaak Walton crowd in ‘71, “Why can’t we as citizens see a copy of the city’s lakefront development plan? We know it exists.”

With Rep. Mann breathing down his neck with that infernal Bill of Rights, Mayor Daley refashioned his construction dreams into a program to protect the lake. See, Mayor Daley was not so keen on state legislation that would control Chicago development, and especially state legislation that would make it impossible to build a $1 billion airport in Lake Michigan eight miles off 55th Street.

Yes, Mayor Daley had been hoping since 1967 to build an airport in the lake—and parrying the inevitable conservationists complaining about the very concept. Yet in May of ‘72, a few weeks after this Council committee hearing, Daley would suddenly announce that he was “unequivocally opposed” to a third major airport in the middle of the lake because of all the “emotionalism and controversy”.

Of course, he didn’t really mean it. Pay attention, because this is another political Penn and Teller trick:

Mayor Daley publicly disavowed his beloved airport in the lake because various studies had come out showing that Chicago wouldn’t need a third airport until the 1990s, and there was no federal money to make it happen. As a City Hall insider put it to the Tribune later that year, “It can’t be built for ten years anyway. Why should Daley take the heat?”

But Mayor Daley truly played a long game. He made sure to leave the door open just a crack for his airport in the lake, though it would not happen for over a decade. Mayor Daley was the epitome of the old man planting trees whose shade he would not live to sit underneath.

Just two examples of how we know this is true:

Testifying at the City Council’s April 1972 lakefront hearing, Daley’s Commissioner of Development and Planning, Lewis Hill, said he thought Rep. Mann’s Lake Michigan Bill of Rights “abrogates and dilutes the abilities of the City of Chicago to continue to preserve the lake.” But Hill also admitted that Mayor Daley’s lakefront plan would allow an airport in the lake.

And in a July 1972 Tribune article, Daley’s Public Works Commissioner, Milton Pikarsky, insisted the lake airport was feasible, despite the extra $100 million it would cost. As for the potential ill effects on Lake Michigan: “Critics do not realize that all questions raised have been resolved,” said Pikarsky.

Back to the April 1972 City Council environment committee hearing on the future of Lake Michigan that would lead to the Lakefront Protection Ordinance:

“We may be witnessing one of the great ecological murders of all time in the lake itself,” Rep. Mann said ahead of the hearing. “If we have no rational plan for the lakefront, we may also see the death of the beautiful lakefront.”

At the hearing itself, Mann testified for over two hours, defending his Lake Michigan Bill of Rights to no avail. “The time has come to put a big, red spotlight on further degradation of the lake,” Mann told the aldermen. “When I think of the possibilities of a third major airport in the lake, I shudder.”

Daley stalwart Ald. Paul Wigoda (49th) didn’t think much of that. “You don’t have a monopoly on preserving the lake,” he snarled.

The Sun-Times’ Harry Golden gave us Mann’s closing, as good as a Shakespeare monologue:

“Why can’t the City of Chicago be for a law that says no more pollution in the lake; that says no more commercial encroachments; that says no more dumping? I’m not here to defend the state…all I am indicating is that Chicago is part of the state.”

We should point out that Mrs. Joanne Alter testified at that April ‘72 hearing too, in the midst of her successful campaign to become the first woman elected to public office in Cook County as a trustee for the Metropolitan Sanitary District.

Joanne Alter also opposed a lake airport. “The purity of the water, the visual aspects of the shoreline, our recreational access to the beaches…are all interconnected matters,” she said. “The measures we adopt to prevent pollution must be closely coordinated.”

Mayor Daley would go on to release a 50-page illustrated lakefront plan with fold-out maps in December 1972. His plan’s legislative partner, the Lakefront Protection Ordinance, would pass City Council with a unanimous vote the following October.

Mann would win re-election without the Machine’s backing—5th Ward politicians had a knack for doing that back then—but he would never pass the Lake Michigan Bill of Rights. Chicago’s lakefront would remain under control of Mayor Daley the city, alone.

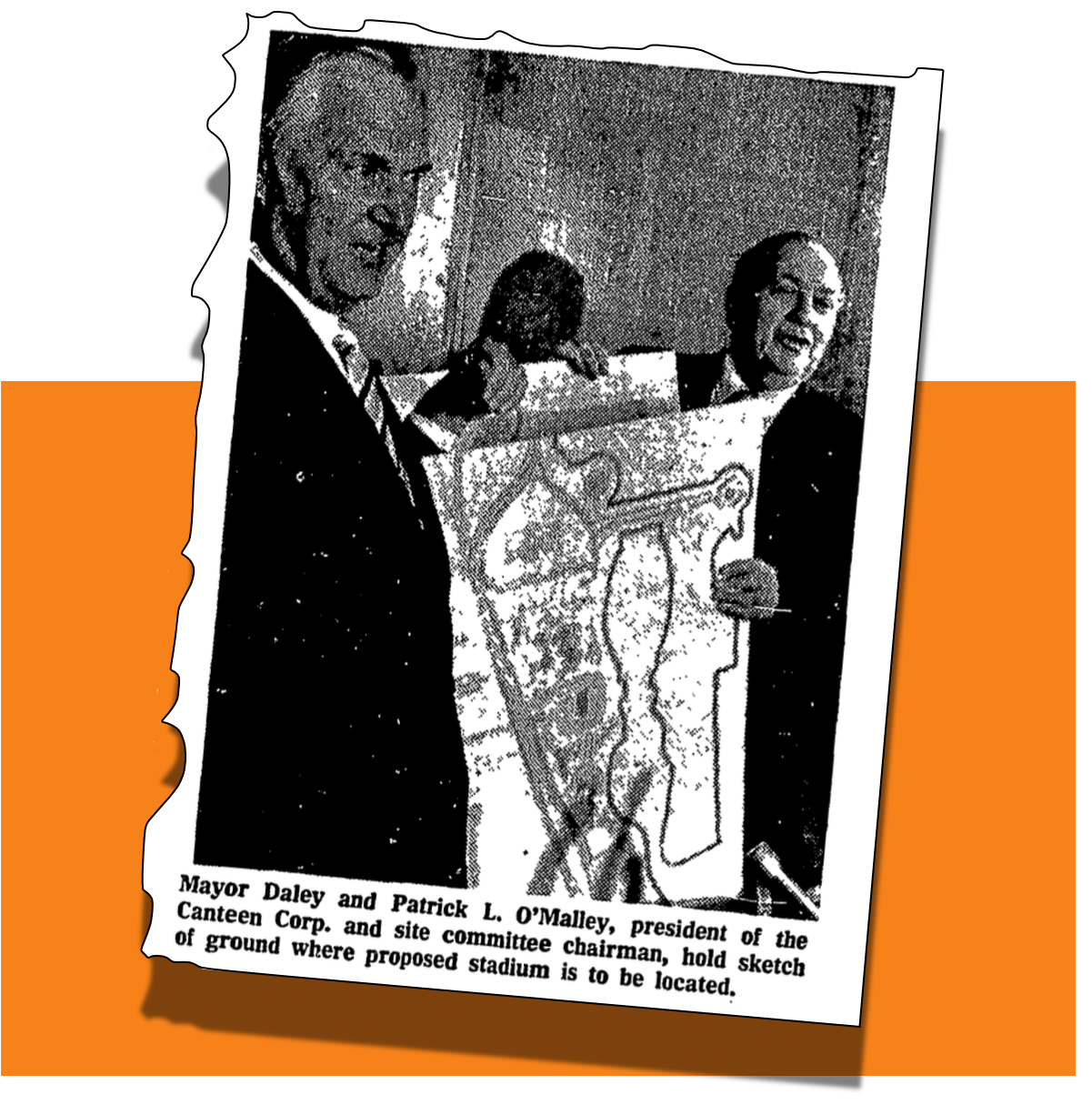

And now we get to Mayor Daley’s 1971 lakefront stadium plan. At the 1972 environment committee hearing, planning commissioner Lewis Hill told the aldermen that a lakefront stadium wasn’t under consideration in Mayor Daley’s lakefront plan. That was technically true, because Mayor Daley had pushed for a lakefront stadium in 1971—and it had not gone well.

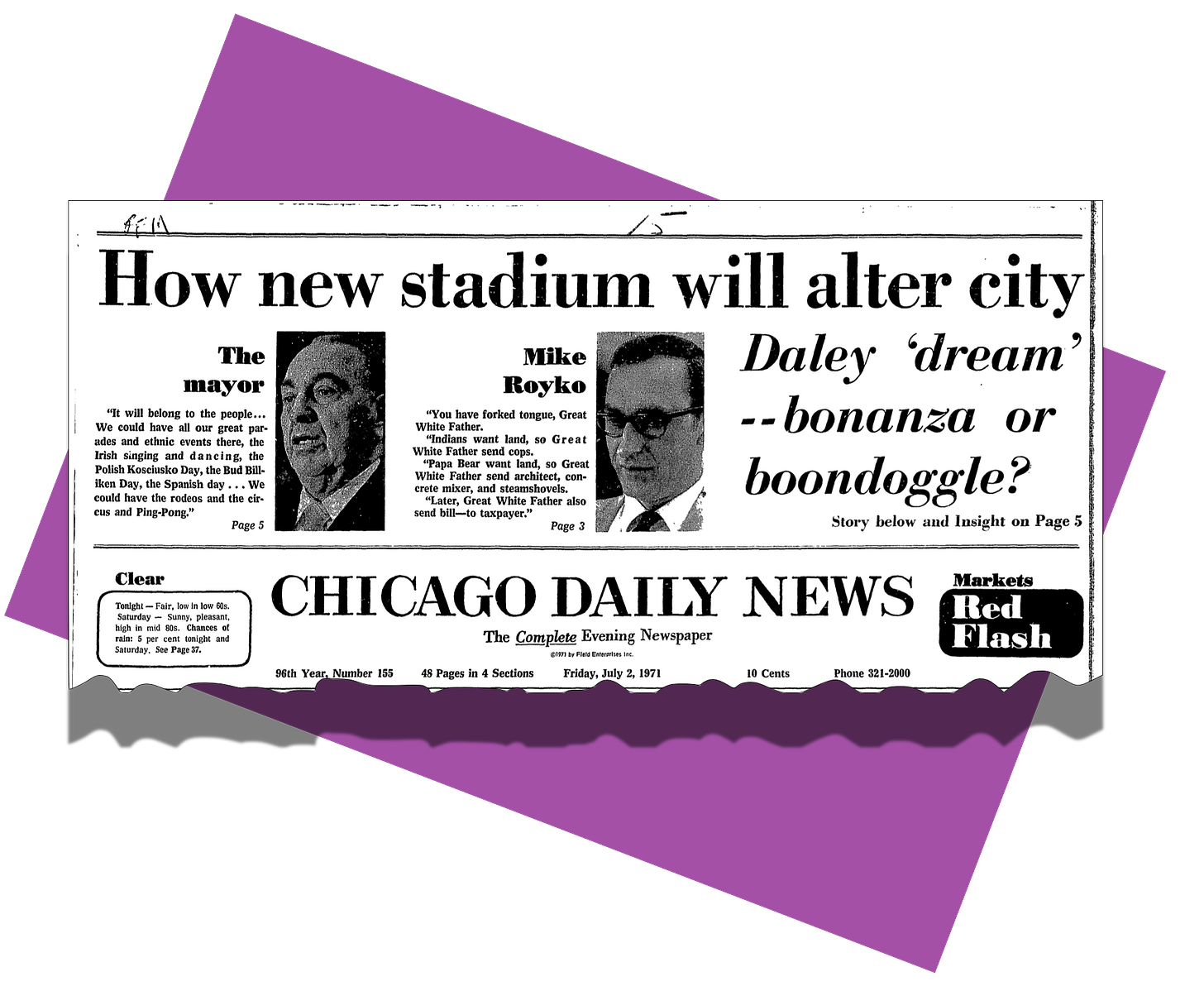

“Daley’s ‘dream’—bonanza or boondoggle?” asked a Daily News front page headline after Mayor Daley revealed his lakefront stadium. Most people and newspaper editorial boards answered “boondoggle.” You can see from the Royko plug in the clip above that Mike wrote a scathing column about it, unfortunately so offensive by today’s standards that we won’t even touch it.

Like the Bears/Johnson plan, Mayor Daley’s included building a big new facility just south of Soldier Field, then tearing the old place down. Mayor Daley’s version was much cheaper, just $55 million, which is $424 million in 2024 dollars. Daley’s 75,000-seat stadium didn’t include a dome, just an overhanging roof above the upper deck seats. The drawing (below) reminds me of the Arlington Race Track that the Bears so recently demolished.

You won’t believe it, but Mayor Daley said we didn’t need a roof because our weather isn’t that bad. See? Mike was right—Mayor Daley was very funny!

The Daley stadium was supposed to be financed by bonds floated by the Public Building Commission, a body Daley had the Illinois legislature create for him to build things. But Chicago papers soon reported that Public Building Commission executive director Robert Christensen had acknowledged that a real estate tax levy would be “the most logical way” to guarantee those bonds, and if the Bears and other stadium renters didn’t cover the debt service, taxpayers would probably plug that hole. Later, Christensen claimed he’d been misquoted.

The Tribune wanted a lakefront stadium anyway. Remember, the 1972 Trib was still struggling to cast off the legacy of uber conservative owner/publisher Col. Robert McCormick, even though the Colonel had been dead for almost 20 years. (Younger readers, if you don’t know what that means but would like to, check our chapter Chicago Newspapers Circa 1972.)

In an editorial soon after Daley unveiled his stadium, the Trib chided “the predictable flurry of opposition,” including the “commonest” complaint “that the stadium will spoil the lakefront and replace ‘the trees and grass and beauty Chicago so desperately needs to conserve.’”

To the contrary, spake the Trib: “In fact, the proposed site does not consist of trees and grass; it is already concrete and asphalt in the form of parking lots. And it does not look out on the lake; it looks across a small yacht harbor toward the airport buildings of Meigs Field.”

When people (like me) speak of the slippery slope that makes it a bad idea to let something like the Children’s Museum into Grant Park, or the Lucas museum onto the lakefront, or the Obama Presidential Library into Jackson Park, this is what we’re talking about. Less than ten years before the Tribune plumped for Mayor Daley’s 1971 lakefront stadium on the grounds that the lakefront there was already just a bunch of parking lots, the newspaper had almost singlehandedly stuck us with McCormick Place and its parking lots. As many readers will know, Tribune political editor George Tagge had lobbied so hard in Springfield for the convention center, and naming it after Col. McCormick, that it was nicknamed “Tagge’s Temple.”

So the Tribune turned the south lakefront into bricks and asphalt, then editorialized that the city might as well build a stadium because after all, the south lakefront was already full of bricks and asphalt.

The Tribune admitted that traffic might be affected by Daley’s lakefront stadium plan, but that wouldn’t be a problem, it informed readers. “In order to avoid intolerable congestion, it will be necessary to extend the subway to serve the stadium, McCormick Place, and the museums in the area. This project is already well advanced,” the Tribune assured everyone.

By the way, I think Bears president Kevin Warren was channeling the old Tribune editorial board at the presentation last week when he took a question from a reporter who asked if it’s been determined how the massive reconstruction of the DuSable Lake Shore Drive will affect South Side drivers.

Here’s Kevin Warren’s answer:

“I mean one of the things we have talked about is, as we said, with progress, there will be some items that will be somewhat complicated. But we have discussed ways that we can work from a traffic standpoint, and it’s no different than when there’s construction work that’s done on freeways.…It’s something that needs to be done, and it’s something that’s overdue, and so we’re confident that residents, people who come to this area, visit this area, that we’ll be able to figure out a way that we can deal with it during the construction process.”

Good to know they discussed it, and they’ll “figure out a way.” But my hunch is that no one on the 1971 Tribune editorial board lived on the South Side, and I’m betting Kevin Warren doesn’t live there either. But I do, and from what I can tell, there are quite a few other people here too. And some of us need to drive downtown, or through it to get somewhere else. So my feelings about Kevin Warren’s answer is, as he put it himself, “somewhat complicated.”

In 1971, Illinois’ U.S. Sen. Adlai Stevenson III dumped on Mayor Daley’s lakefront stadium too: “I have not seen the report….But I just cannot see that a city with all the resources of Chicago can’t contrive a way to develop a good, accessible stadium without despoiling its precious lakefront. There are other possible sites.”

So Mayor Daley backed off his 1971 stadium plan rather quickly. The Tribune editorial board soon lamented the stadium’s dismal reception: “In the language of the sociologists it would appear that critics of the plan have overreacted,” sighed the Trib. “Like a mob at an old fashioned lynching, they have slashed and beaten the stadium project and now seem poised to dance in celebration of its ignominious death.”

Less than a week after he’d announced the lakefront stadium, Mayor Daley was ranting about “polluted and twisted minds”opposing it during a City Hall press conference.

“‘Put this on the first page, all you lovers of Chicago,’ snapped the mayor as he opened his press conference,” wrote the Trib’s Edward Schreiber. “‘The stadium will be located one-half to three-quarters of a mile from the lake. Return of property for park land will be 65 to 70 acres…Soldier Field and parking now are 98 acres. The acreage for the stadium will be 10, and much of the parking for the stadium will be on Illinois Central air rights.

“‘The problems are not all resolved. We don’t know all the answers. But there will be no increase in real estate taxes. There’ll be no general obligation bonds, and no property tax.” From Schreiber’s coverage, we can assume all those sentences deserved exclamation points that a careful Trib copy editor declined to use.

[Note: I couldn’t find a recording of this particular press conference, so here’s the famous one following the 1968 Democratic convention when Mayor Daley so memorably told reporters, "Gentlemen, get the thing straight once and for all – the policeman isn't there to create disorder, the policeman is there to preserve disorder.”]

A few more Trib excerpts from Daley’s stadium press conference:

“The people will use this stadium. We’ll have customers. Chicago Circle Campus [football teams] will play there. Do any of you wise gentlemen know how many a university will draw on a Saturday afternoon?”

“Probably 5,000,” cracked a wiseguy reporter, and that set off Mayor Daley all over again.

Here’s another good one:

“The people who talk of losing money are the same ones who talked about losing when they built the first shacks in Chicago. They said it was a bad town and went to Shawnee-town [in Southern Illinois].”

Mayor Richard Joseph Daley’s press conferences were probably better than Mayor Richard Johnson Daley’s, but while we’re at it, here’s the February 2024 press conference that touched off a round of the current “Mayor Johnson needs a course correction” articles. The spark: Johnson refused to tell reporters whether or not, in a meeting with Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker and Cook County President Toni Preckwinkle, he had agreed to add $70 million of city money to $182 million in new state funds and $70 million in new county money for the migrant crisis then besetting the city—and then reneged. The big moment starts at 33:00 in this video.

Back to Mayor Richard J. Daley’s 1971 stadium presser. According to the Trib’s Schreiber, Daley particularly lashed out at the TV reporters at this press conference. I wonder if Walter Jacobson was there?

“It is the nature of guys like yourselves that ruins everything,” Daley yelled. “You great geniuses. What the hell. You ought to start boosting and quit your type of snickering and small town business. These over meticulous newspapers and radio men…”

But here’s the best part about Mayor Daley’s wild press conference: Mike Royko wrote a column about it! Here’s a look at Mike’s account:

“Mayor Daley called us together Tuesday because he didn’t think people really understood his idea for a new lakefront football stadium,” wrote Mike.

“And those who understand least are saying taxpayers will probably have to foot the bill for ‘Halas’ Palace.’

“Among these confused individuals are some of the mayor’s top aides, as well as just about anybody who can add up a row of figures. They all agree that the stadium won’t pay for itself.”

Mayor Daley, per Mike, insisted that Soldier Field occupies 98 acres, while the new stadium would only take up 10 acres, so 65 acres would go back to parkland.

“These were fascinating figures,” notes Mike. “A new stadium on one-tenth the land of Soldier Field would indicate that tiny elves and dwarfs will play games there.”

Later:

“Question: Wouldn’t anti-stadium public opinion change the mayor’s mind? (Now, I ask you—is that not a reasonable question?)”

I think Mike is subtly letting us know that he asked Mayor Daley this question.

“The mayor’s cheeks turned the color of a freshly caught Florida red snapper, and he said:

“‘Only a twisted mind like yours would say that.’”

I think maybe Mike asked the next question too:

“Another question: Isn’t George Halas the chief beneficiary of the new stadium?

“The color of the mayor’s face deepened. He appeared ready to pop.

“‘That’s the words of a twisted and polluted mind.’”

At that point, Mike said Mayor Daley began a “rambling monolog on the wondrous uses” for a lakefront stadium. The Olympics; track meets; even the annual Venetian Night yacht parade…

…and St. Patrick’s Day, Chicago’s holiest day of the year. Here’s Mike’s description of this portion of Mayor Daley’s performance:

“‘…An’ we’ll have the St. Patrick’s Day parade there and the people will be sittin’ in the stands watchin’ and they’ll be gettin’ up and doin’ the jig…’

“The mayor, at this point, laughed and did a tiny jig to demonstrate how the happy throngs would be jigging in the stands.

“‘…An’ we’ll have the Kosciuszko Day there for the Polish people and we’ll charge for it and the people will be glad to pay.’”

Mike found that odd since, at that time, it was traditional for Chicago’s Polish community to gather for free on Kosciuszko Day in Humboldt Park, in what was then their neighborhood, around a statue of Thaddeus Kosciuszko astride a horse. A native Pole and skilled engineer, Kosciuszko designed American fortifications during the Revolutionary War. His statue was later relocated near the Shedd Aquarium.

Of course, Mike has a great closer:

“The mayor forgot to mention one gate attraction for his dream stadium—a knockdown, thrill-a-minute contest that would draw a packed house:

“One of his press conferences.”

Well, we know “Halas’ Palace” did not come to pass. As mentioned earlier, a year after this press conference circus, Planning Commissioner Lewis Hill would testify during the 1972 environment committee that there was no lakefront stadium in Mayor Daley’s upcoming lakefront plan. And technically, as we also already noted, that was true—the plan did not include a lakefront stadium.

But again, as with the airport-in-the-lake, Mayor Daley kept his options open when he announced a lakefront plan without a lakefront stadium:

“Asked if [the plan] would prevent construction of a lakefront sports stadium, the mayor replied: ‘I can’t answer that at this meeting. On the lakefront immediately, I’d say no. But half a mile inland would be something else.’”

At least, I think that was Mayor Daley.

A masterful takedown of our truly delusional & incompetent out of his depth mayor, Cate!

I wonder what he's personally going to get out of the Bears deal?

Will it be big envelopes of cash under the table?

No show jobs for his wife & children?

Hey, old-timer, love the Time Tunnel references! I wonder how many of the youngs will get it?

(and loved the exposition of the parallels)