To access all website contents, click HERE.

Dear Readers: We must dwell in the present at least partially again this week. Somebody wants to take all the fun out of Chicago government.

The Better Government Association is the coolest Chicago organization there is, which is quite something since it started in 1923 with what must have been a very uptight group of upstanding citizens. We know this because they were led by the head of the Anti-Saloon League.

But now the BGA, which I dig so much, is coming after my beloved alderpeople*—specifically, the ability of alderpeople to rant, grandstand, memorialize, laugh, cry, and fight for hours on the City Council floor about anything under the sun, all before the meeting gets past the first couple of lines in the agenda.

The alderpeople like talking. The BGA is tired of listening.

*I still think “aldermen” in my head, no matter what comes out of my mouth at any particular time. I’m going with “alderpeople” today because it worked for the headline. Language matters, but “alderwoman” etc. is irritatingly long even with just one extra syllable. Forced to choose something new, I go with “alder” for simplicity. But it sounds weird. Why can’t we pitch the new terms altogether and agree that the word “men” part of “aldermen” is an also an abbreviation of “women,” and thus it’s “inclusive.” In fact, let’s pretend linguists don’t exist—there aren’t very many, we can ignore them—and fix this by simply deciding among ourselves that the word “men” is merely a derivation of the word “women.” Men are safely shunted aside these days, and like the value of money, language is all in our heads. It is what we say it is. So—problem solved. Perhaps that will draw some comments.

BGA policy and budget analyst Geoffrey Cubbage has meticulously broken down every City Council meeting, minute by minute, since they started officially recording during the Lori Lightfoot regime. I hope mental health is covered under the BGA insurance plan. Cubbage found that under Lightfoot and now Brandon Johnson, the Council spends about one third of its meeting time blathering about honorary resolutions.

During “meetings where resolutions were heard, the average time spent speaking on non-binding business was 1:11:56 during the first year of the Johnson administration, compared to 1:12:11 under Lightfoot.”

The BGA advises that Chicago should reign in the alderpeople’s galloping tongues, like they do in New York and Houston.

“New York’s city council limits members to a timer-enforced one minute of remarks on honorary resolutions,” writes Cubbage, “while Houston’s will only hear up to three ‘presentations regarding public interest’ per meeting, each one limited to a maximum of ten minutes.”

Los Angeles shunts the resolutions to the end of the meeting, like the last part of movie credits running over a black background that nobody watches. The part where they list the gaffers.

I’m sorry to say that my esteemed colleague from The Mincing Rascals podcast, former Tribune columnist Eric Zorn, supported the BGA’s dangerous position in his Substack, The Picayune Sentinel.

“The obtuse self-importance of the alders and their honorary resolutions is galling,” Eric wrote, noting the BGA’s conclusion that “the council’s current practice means that substantive matters are often not addressed until two hours or more into a meeting”.

Hm. This is all true enough. In the post Council Wars era, the lengthy resolutions took root around 1998, when Mayor (Richard M.) Daley tried ingratiating himself with Chicago first responders who generally hated his guts. So rather than occasionally opening meetings with a salute to a heroic police officer or firefighter, Daley started doing it every single time. Soon, everybody who had a chair in the Council chambers had to get in on it. I covered the Council from 1994-2004, and around 2000, I had to start bringing a muffin with me or I’d be too hangry to take notes through the end of the meeting.

But.

Chicago normally prides itself on going its own way. We don’t want nobody nobody sent, we don’t need no stinking badges, and any other similar pop culture allusion.

We pretend we don’t care about New York. We really don’t care about Los Angeles— though we’d love their weather minus mudslides, earthquakes and suffocating wildfire smoke. We’d rather be dead than be Houston.

We are the ones with all the fresh water, and they’ll be wishing they were us some day soon.

Yet the BGA wants us to imitate all three of those cities, by pushing City Council resolutions to the end of meetings and slapping a tight time limit on speeches.

“I’d recommend ditching them altogether,” says Eric Zorn.

That’s a problem.

Mayor Brandon Johnson’s City Council has been exceptionally entertaining so far within the official order of business, because he has little control even over his own allies. But we can’t count on that interesting state of affairs forever. Historically, it has not been Chicago’s natural set point.

So as longtime Council watchers know, some of the best moments happen during the honorary resolutions, which are sandwiched between the opening prayer and the part where the actual laws get passed.

During resolutions, anything goes.

For instance, there was the time in 1994 when Ald. Ed Burke introduced a laudatory resolution for a crooked politician whose crimes paralyzed the nation for months and left several generations of Americans permanently disillusioned.

Burke gave a lengthy homage to recently deceased President Richard M. Nixon.

Ald. Tom Murphy (18th) was the only one who looked unsure about the whole thing. Murphy was a congenial young alderman with an endearing regular guy Chicago accent. He went on to snare a Cook County circuit court judgeship in 2006 after getting drawn out of his ward during the creation of more majority-Black districts. He’s always drawn a “qualified” and “retention” rating from various bar associations. You have to love that in 2001, when his 18th Ward had already become majority Black, Murphy asked to join the Council’s Black Caucus to better serve his constituents. The Black Caucus said no.

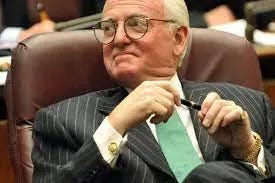

In 1994, Ed Burke had long been the most powerful alderman in the Council as head of the Finance Committee.

To give you an idea of why Ald. Murphy spoke uncertainly regarding Uber-political villain Richard Nixon, and why nobody else uttered a word, here is some of what Murphy said when he testified almost exactly 30 years later during Burke’s 2023 trial on racketeering, bribery and extortion charges. (Spoiler, Burke got convicted.)

“Ald. Burke can be extremely intimidating, and you wanted to make sure you can be as responsive as possible….He was the most senior alderman of the City Council and, as head of the finance committee, he had a lot of power and influence…..If Ald. Burke asked you questions it could be terrifying.”

Now you get the picture as young, not-senior, not powerful, freshman Ald. Murphy slowly began speaking on a resolution to honor disgraced dead President Richard Nixon:

“Ordinarily I never speak ill of a person who’s deceased,” Murphy started, tentatively, feeling his way for verbal pitfalls. “And I feel a little uncomfortable even getting up and saying this, but I don’t want to be part of a resolution honoring a president who would have been impeached if he remained in office and only resigned to save that embarrassment.”

Up on the podium, Mayor (Richard M.) Daley winced.

“I would say that you extend your condolences to anyone, whether you like them or not,” Daley said sorrowfully, cocking his head at Murphy as if contemplating whether to send him to bed without dessert.

Ald. Dorothy Tillman was walking to her seat.

“You hafta be dead to have something good said about you!” Tillman snickered loudly to everyone as she passed. “I don’t wanna be dead! Everybody wanna go to heaven, but no one wants to die!”

These are the moments that will be lost in time, like tears in rain, if the BGA gets its way. Resolutions are sometimes the only thing that salvage a City Council meeting.

So on this one issue, I must part ways with the BGA. All I have to stack up against their carefully curated numbers is a random jumble of anecdotes, but I think they’re more fun, and it seems like politics could use a little more fun in these divisive days.

So I’m going to share five of my favorite resolution moments—including the time Eartha Kitt practically climbed in Mayor (Richard M.) Daley’s lap. But first, let’s take an illustrated look at the Better Government Association. This is, after all, a history site.

And how many people know anything about the BGA, besides the fact that they sound like reporters who carry badges and guns, which is part of what makes them so cool?

Scroll down to Resolved: I love City Council resolutions or click here if you just want more alderpeople stories.

The Untouchable BGA

“The BGA came to life in the Prohibition Era,” the BGA’s website explains. “Alcohol was illegal yet more than 5,000 taverns and speakeasies thrived. City aldermen, who won their votes through fraud and ballot-box stuffing, ran illegal gambling houses and brothels. Chicago Mayor William ‘Big Bill’ Thompson — known as one of the worst mayors of any major city at any time in the country’s history — was openly in cahoots with the infamous Al Capone mob.”

The BGA soon expanded beyond fighting demon alcohol to battling general public corruption, chiefly by evaluating political candidates and giving nonpartisan endorsements.

Perhaps they were trying to make up for the fact that their original members and leaders from the Anti-Saloon League had endorsed Big Bill in 1916. That was a lot to live down.

In its capacity as the fair arbiter of all good candidates great and small, the mid-20th century BGA drew praise from Cook County Clerk Richard J. Daley for its “splendid civic service.” That changed after Clerk Daley became Mayor Daley, perhaps in part because the BGA did not help Daley make that transformation.

To be fair, nearly everybody endorsed Daley’s 1955 opponent, Ald. Robert Merriam (5th), as the Daily News’ helpful chart above reveals. The BGA’s dismissal must have smarted nonetheless—though not nearly as much as the BGA’s work in subsequent Daley administrations. That’s because Daley’s mayoral years dovetailed precisely with the BGA’s reincarnation as investigative journalist badasses, partnering with local papers and TV news programs.

The 1970s were truly a golden age for the BGA. The BGA’s glamorous president, Richard Friedman, known as much for his cool car and hot air ballooning, left to run against Mayor Daley in 1971. He lost, of course, but for a few exhilerating months, Friedman was all over the news. Equally glamorous Daily News gossip columnists Jon and Abra noted that Friedman just couldn’t shake “his dashing movie star image,” because he looked like Ben Gazarra.

I guess I can see it. I wouldn’t call Ben Gazarra dashing, but whatever.

For Younger Readers: Physically, Ben Gazarra was more the 1970s Jeremy Renner—and nothing wrong with that!

While Gazarra was a prominent star of stage and film who became particularly prominent due to his parts in John Cassavetes films like “Husbands” with the incredible Peter Falk (Columbo), Younger Readers may remember him for his menacing performance as pornographic producer Jackie Treehorn in “The Big Lebowski.”

BTW, stay tuned for more on Dick Friedman when we get to the 1971 election in the ongoing mini-biography here of Mayor Daley, election by election, which will culminate in the Great Chicago Reporter’s Rebellion of 1971.

Actually, since this is a newsletter, the thing to do is subscribe for FREE and get new posts directly to your emailbox.

Glamorous Dick Friedman was followed by low-key Terry Brunner, who led the BGA for almost 30 years, garnered lots of press, and looked so much like a younger Johnny Carson.

This picture, from a 1974 profile by Ed Planer in the terrific but short-lived The Chicagoan magazine, doesn’t come close to showing the eerie resemblance. I met Brunner once and almost did a double take.

Under Brunner, the BGA and Sun-Times investigated Mayor Daley’s righthand man, Ald. Thomas Keane (31st), then the second most powerful man in Chicago. Their work led to Keane’s 1974 federal indictment and conviction for 18 counts of conspiracy and mail fraud. U.S. Attorney James R. Thompson, soon to be Illinois Gov. “Big Jim” Thompson, listened to the verdict “with tears in his eyes,” per the Sun-Times’ Bob Olmstead. Thompson called it “a historic day for the city of Chicago.”

Ald. Keane had found so many ways to use his power and influence to make money, the trial took over a month.

At the exact same time, Cook County Circuit Court Clerk Matt Danaher was under federal indictment on conspiracy and income tax charges stemming from his own Sun-Times/BGA investigation. That probe “revealed allegations that Danaher had received pay-offs from the builders of two South Side subdivisions.” Danaher died one month before going on trial.

Danaher had fallen from Mayor Daley’s good graces just before the Sun-Times/BGA investigation, due to cheating on and leaving his wife. He could not resist the swinging new 1970s lifestyle. I picture him as Pete in “Mad Men,” the first executive in the office to grow sideburns.

So Mayor Daley dumped Danaher. Mayor Daley was not the Don Draper in that scenario. He was very much what they called “a square” in those days. But until their break, Danaher lived a hop skip and jump from Daley in Bridgeport.

Danaher was so close to Daley that he figured prominently in the masterful first chapter of Boss, in which Mike Royko describes a typical Mayor Daley day. Royko follows Mayor Daley’s morning routine starting in his bungalow at 3536 S. Lowe, then moves to Danaher:

“Down the street, in another brick bungalow, Matt Danaher is getting ready for work. He runs the two thousand clerical employees in the Cook County court system, and he knows the morning routine of his neighbor. As a young protege, he once drove the car, opened the door, held the coat, got the papers. Now he is part of the ruling circle, and one of the few people in the world who can walk past the policeman and into [Mayor Daley’s] house, one of the people who are invited to spend an evening, sit in the basement, eat, sing, dance the Irish jig….Danaher is one of them, and his relationship to the owner of house is so close that he has served as an emotional whipping boy, so close that he can yell back and slam the door when he leaves.”

So it figures that by the time the BGA was helping put away his pals, Mayor Daley was calling the group “an arm of the Republican Party”. What Chicago political epithet could be worse? Mayor Daley described the BGA as “looking through keyholes and over transoms and everything else.”

If Mayor Daley said that about me, I’d use it as my slogan forever. I’d get it made into a big neon sign and hang it on the building.

Here you go, BGA, no charge:

Plus, the BGA worked with the Sun-Times and 60 Minutes on the absolute coolest newspaper investigation of all time, The Mirage, in 1978. A curse upon the Pulitzer board that didn’t reward everyone involved. Some tightasses thought reporters shouldn’t do their job, basically, as if carefully documenting a diabolical sting operation was the equivalent of the Chicago American’s Harry “Romy” Romanoff calling Richard Speck’s mom and pretending to be her son’s lawyer to get good background on a serial killer.

Here’s a great tidbit from that Chicagoan profile of Terry Brunner: Bill Recktenwald, previously a State’s Attorney investigator, operated in the ‘70s as the BGA’s “modern-day Lon Chaney” while serving as its chief investigator, per author Ed Planer.

“When, for example, the BGA probed substandard conditions at ‘halfway houses’ for retarded adults and former mental patients, Recktenwald posed as a mentally retarded adult in order to gain admission to one of the homes,” wrote Planer.

“It was the most difficult assignment I ever had,” Recktenwald recalls. “I had to sit in one of those homes and pretend that I was unaware of what was happening all around me. Once, the picture on a TV set kept rolling over and over and I had to sit there for two days and act as if I didn’t care, or know, that the set was broken. It was really difficult.”

Just occurred to me that Younger Readers won’t know what this means. Here’s a video to give you an idea.

BGA investigations are staples of daily newspapers in the world of THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972. Here’s my favorite TGIF post on the BGA, set off by red lines. This was the BGA’s funniest 1972 work, so it figures they partnered here with Chicago Today:

April 24, 1972

Chicago Today: ‘Workers’ strain to look busy

Chicago Today teamed with the BGA for another fun investigation—savor this delicious helping of government waste!

“City employes at O’Hare International Airport work harder at pretending they’re working than at actually washing windows, floors and ceilings and performing other routine custodial tasks,” the investigation found.

Yum!

“Maintenance personnel in white, khaki or blue uniforms watched airplanes, ogled girls, took coffee breaks and looked for abandoned change in pay phones.”

Oh, Younger Readers, that was a thing! You probably don’t even know what a payphone looks like. But if you tried to make a call and nobody answered the phone, the coins you deposited at the top of the payphone in those little round holes (see below) were returned through a slot at the bottom. Surprisingly, if you randomly stuck your finger in a payphone as you passed by, you often found a few coins.

“Several employees were clocked spending only an hour working in the course of a seven- or eight-hour work day.”

“The examples of loafing explain, in part, why payroll and custodial costs at the world’s busiest airport have doubled in the last five to six years….From 1966 to 1972, the budget for O’Hare has tripled, from $12 million to $35.8 million…and janitorial services have doubled, from $1.09 million in 1966 to a projected $2.1 million for 1972.”

“Investigators who observed employes at O’Hare say that the longest distance between two points is the ‘O’Hare shuffle’—which the employes use to meander from one place to another.”

Just one of the priceless anecdotes:

“In one instance, a janitor sleeping in a storage closet in the women’s restroom was awakened by a maintenance man who yelled into the rest room for her.

“She cleared the rest room, told the men to come in and asked them to fix a toilet which, she said, had been leaking for two weeks. They ignored her request and left.

“‘They never do nothing,’ she grumbled. ‘All they do is walk around, walk around.’”

Here’s the headline for the sidebar. We’ll stop here though, because we’ll all get a sugar high if we keep this up.

This being a Chicago history site, I’ve covered the past. But the BGA is alive and well. Even with ups and downs of funding and so forth over the decades, it’s continued to be a scourge for crooked politicians. Most recently, veteran Chicago Channel 7 political reporter Andy Shaw took the helm from 2009-March 2018 and, per the website, organized the BGA into five units— Investigations, Advocacy, Communications, Watchdog Training, and Reporting and Administration.

Shaw was succeeded by veteran Chicago journalist David Greising, whose name is probably most familiar to readers as the Tribune’s former business columnist. BGA investigator reporter Madison Hopkins won a Pulitzer Prize with the Tribune’s Cecilia Reyes in 2022 for “The Failures Before the Fires,” a series that revealed 61 Chicagoans died in fires over five years in buildings with fire-safety issues the city knew about.

Now back to our regularly scheduled alderpeople.

Resolved: I love City Council resolutions

So many resolution moments to choose from—too many, as the BGA will tell you. I’ll confine this to five meetings, or the BGA might come after me too.

1. November 2, 1994

Whenever an alderman leaves the City Council or this world, the air in the Council chambers is rife with possibilities for good speeches. At this 1994 meeting, the aldermen—that’s what we called them back then—were hailing the retirement of longtime Ald. John Madrzyk (13th).

Madrzyk had started in City Council in 1973 under the real Mayor Daley.

Background/Foreground: Two weeks before this meeting, Madrzyk had resigned abruptly when 13th Ward Democratic committeeman, Illinois House Speaker and all around Southwest Side Democratic boss John Madigan told him to. (Yes, the same Madigan facing an epic corruption trial in 2024.) Mayor (Richard M.) Daley coincidently offered Madrzyk a job in the city’s special events office, just as Madigan kicked him out. Since Madrzyk had chaired the Council’s Special Events Committee, he arguably had experience for the job—but he’d also been employing his daughter-in-law as a ghost payroller on the committee staff. Madigan presumably knew that, but the public wouldn’t find out until 1997, when Madrzyk’s daughter-in-law confessed to federal investigators running the Operation Haunted Hall probe. Madrzyk would eventually plead guilty to employing four ghosts, plus extorting kickbacks, rather than watch his daughter-in-law testify against him in court.

But that was all ahead of Ald. John Madrzyk as his colleagues honored him on November 2, 1994. Three speeches stood out.

First, of course, Ald. William Beavers (7th).

“I first came down [to the City Council] when there was turmoil,” said Beavers, in his voice deeper than God’s, setting the scene for his Madrzyk anecdote.

Beavers was reminding everyone that he took office in 1983 with Mayor Harold Washington, so he walked right into the legendary Council Wars. Unlike the Council of John Madrzyk’s early days under the real Mayor Daley, who controlled the Council with an iron hand and turned off microphones if the few independent aldermen got out of hand, Beavers landed in a free-for-all.

Now, Beavers soon became an imposing Council presence, helped by his sheer height and that voice. IMHO, he tied for best dressed alderman with Burke—but Beavers had more style, with his gold chain bracelet big enough to use as a weapon. Ald. Beavers would be convicted of tax evasion in 2013 for using campaign money to gamble and not reporting it as income. As the Tribune’s Jason Meisner reported at sentencing, “Prosecutors alleged at trial that Beavers used his campaign funds from 2006 through 2008 as if they were cash machines, blowing the money on slots at the Horseshoe Casino in Hammond. While Beavers was not charged with any gambling-related offenses, casino records presented at trial showed Beavers clocking in and out of the casino multiple times during the same days. In all he lost nearly half a million dollars over the three-year period, according to evidence at trial.”

Beavers claimed that the feds asked him to wear a wire against Mayor (Richard M.) Daley’s brother John, and he declined, since as he pointed out, he is not a stool pigeon. The feds denied that ever happened. Regardless, Beavers took his six-month sentence stoically in the courtroom, then explained his attitude to reporters afterward: “Like I say, I ain’t begging for nothing. I don’t beg my woman, so you know I won’t beg the judge, all right?”

At this 1994 meeting, Beavers told his colleagues that Madrzyk had an interesting spin on appreciating the constant floor fight that characterized Council Wars as Beavers started his first political office:

“And Madrzyk took me to the side and he said ‘Beavers, let me tell you something.’ He said ‘I like the way this council is today.’ He said ‘I can talk.’ He said ‘When I first came down here,’ he said, ‘I spent three years before I could say one word.’ He said one day [the real] Mayor Richard Daley called him upstairs and he said he was trembling, he was trembling like this.”

Beavers held his hands up and shook them to demonstrate.

“He thought he had messed up. He said the mayor told him, he said, ‘You can talk a little now. Just don’t go [overboard].’”

Next up, Ald. Bernie Stone (50th):

“I can recall vividly during the snowstorm of 1979, where John Madrzyk and Fred Roti insisted that, when I said I wouldn’t shave until the streets of my ward were clear of snow, they held me down and used an electric razor and shaved me. They said, ‘You look terrible, you even look worse than your streets.’”

“I would refresh my colleagues’ recollection,” Stone went on, “that the Chicago Tribune at one time honored John Madrzyk as the number one alderman in the city of Chicago, the best.”

As Stone’s last words dropped, Aldermen Ted Mazola and Carole Bialczak, who sat near the press box, turned to stare incredulously at Tribune reporter Robert Davis.

Poor Bob cringed in his seat and then threw up his hands, sputtering, “That was a joke! That was a joke!”

Finally, let’s hear from then-young Ald. Brian Doherty (41st), the Council’s lone Republican, still in his first term at that time. Doherty was a former Golden Gloves boxer whose impeccable flat Chicago accent was sprinkled with a healthy dose of the traditional substitution of "d" for "th" or "tr". And he was always so sincere.

“John Madrzyk was a good friend of mine when I was a freshman,” said Ald. Doherty. “First year in the council, John came to my office and said, ‘Kid, anything I can do to help you, let me know.’ He also one time, I lost my temper with someone that I thought had done me wrong. John knocked on my door and he came in. He says, ‘Hey kid.’ He goes, ‘This ain’t for real. You gotta take the time to relax or you’ll never last.’ And that was probably the best advice I got from anyone down here.”

While you’re here, check out Mike Royko 50+ Years Ago Today, where we explore Mike’s columns to give historical, political and pop culture context so today’s readers can fully appreciate his genius.

2. May 16, 1996

Eartha Kitt, still sizzling at 68, came to town in spring 1996 starring in a one-woman show about Billie Holiday, “Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar and Grill.” She got rave reviews and a snippet in Kup nearly every day as she cruised the city’s hot spots.

And she amused herself by teasing Mayor (Richard M.) Daley. At the May 16 Council meeting, Ald. Shirley Coleman (16th) introduced a resolution honoring Eartha Kitt’s career. After the alderpeople, Kitt spoke too—which was unusual, but this was Eartha Kitt. The only more famous person I ever saw honored at a Council meeting was Sammy Sosa in the middle of his big home run spree.

FYI, in her remarks below, Eartha Kitt is referencing the famous 1995-96 federal government shutdown when Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich thought he was entitled to deep budget cuts and Democratic President Bill Clinton disagreed—though the shutdown had been over for months before this meeting.

“The interesting thing about being here this morning also, among you gov-ern-mental officials,” Kitt trilled vampishly, “is that I see more seats filled here than I see in the House when I’m watching C-Span. So I’m very happy to say that at least here in Chicago it seems that the government is working.”

Mayor (Richard M.) Daley began blushing as Kitt leaned toward him.

“I also kind of feel that since I’ve known his father very well,” she purred, “that we can talk when we get past all the rhetoric. Then we’ll have something more serious to talk about.”

Daley’s blush grew deep enough to give him the bends, and he cast his eyes up at the ceiling.

Kitt continued:

“But at the same time I do feel that those who are not seen in the seats in Washington when I watch C-Span and they close down the government, I would like to ask you, May-uh, is it right for us taxpayers to be paying for those days that the government wasn’t working?”

“We shouldn’t!” Daley mumbled quickly.

“And he says we shouldn’t!” Kitt smiled. “Therefore, what can we do about that?”

Daley turned redder still, then blurted out, “Allow myself and the City Council to run the government, hahahahahaha!”

Mayor (Richard M.) Daley was referring to the fact that he generally got his budgets passed as efficiently as his father did, with no more than one or two defectors in the final vote.

3. December 19, 1996

Ald. Ed Burkę chaired a meeting of his Finance Committee just before the main City Council meeting. Even in 1996, he was one of the longest-serving aldermen on the council. He would serve 54 years in 13 terms, wisely choosing not to run for re-election after his 2019 indictment.

The Finance Committee got into it over Mayor (Richard M.) Daley’s proposal to drop Good Friday as a paid city holiday, because a federal appeals court had just ruled that observing Good Friday in schools violated the separation of church and state. Several aldermen kept pestering the poor city lawyer dispatched to the meeting to defend the administration’s proposal. They refused to understand why Good Friday was different from Christmas.

Ald. Burkę gazed around the huge, nearly empty Council chambers as the others nattered on. After a while, he observed that he half expected mailmen to burst in the doors with bags of mail for Santa Claus.

Ald. John Buchanan (10th), bless him, said it would take at least a week for Chicago postal workers to get mail for Santa just from one end of the city to the other, so that—continuing the allusion to “Miracle on 34th Street”—so here, Kris Kringle would likely die in an insane asylum rather than be vindicated by bags of children’s letters.

Later, at the full Council meeting, Ald. Burke unexpectedly introduced a resolution affirming the existence of Santa Claus.

“When Chicago children ask their parents if there’s a Santa Claus,” Burke declared, “parents will be able to say, ‘Well of course there is darling, the City Council said there is!’”

“Uh-uh, Alderman Burke, I see colleagues rising,” warned Ald. Lorraine Dixon (8th), who as president pro tempore was presiding for an absent Mayor (Richard M.) Daley.*

Ald. Ed Smith (28th) spoke first.

“I have some questions about this Santa Claus stuff,” Smith began.

“Oh Alderman Smith, you don’t believe in Santa Claus?” asked Dixon plaintively.

“Now wait a minute, I’m not saying that. I just, I have some questions, OK?” said Smith. “And I’ve been, I’ve been trying to get some answers to these questions for a long time, so perhaps this is the right place.”

Smith said his mother was never able to tell him where Santa Claus got the money to buy toys for everyone, or how Santa knew if young Smith had been naughty or nice.

“So if you can answer these questions, I’ll vote for the resolution,” he finished.

“OK,” said Dixon. “Alderman Smith, in answer to all your questions, it’s magic.”

Ald. Billy Ocasio (26th) went next.

“There’s a few things I need to know,” said Ocasio, feigning sincere concern. “I mean, if Santa Claus is a resident of the North Pole, where does he vote?”

“Now that’s a good question,” said Dixon.

“Does he vote Democrat? Does he vote Republican?” Ocasio went on.

“Another good question,” Dixon agreed.

“Personal privilege, Madam President,” called Burke.

“Personal privilege,” nodded Dixon.

“Santa Claus votes by absentee in the 14th Ward,” smirked Burke, proud of his ward’s renown for large numbers of absentee ballots, a classic Chicago Machine tactic for boosting Democratic voter turnout. Burke’s 14th Ward had generated 2,440 absentees in the 1995 primary, more than any of the six wards that the Chicago Board of Election Commissioners wanted to investigate for absentee vote fraud that year.

*Dixon was the first woman to serve as president pro tempore. She also chaired the powerful Budget Committee. When she died tragically young in 2001, Mayor (Richard M.) Daley named Ald. William Beavers to the budget chair, Ald. Danny Solis to president pro tem, and State Rep. Todd Stroger to fill her elected office. The irony of Daley’s appointments didn’t go entirely unnoticed on the Council floor. As a female staffer set up for a meeting soon after, she looked around and observed out loud, “I was just thinking of Lorraine Dixon. It took three men to replace one woman.”

Jump into the Chicago History Rabbit Hole section for topics like Chicago’s first convicted alderman, the glamorous history of the Shoreland Hotel, and the devastating Iroquois Theater fire.

4. April 5, 1998

As Ald. Ed Burke’s longtime comrade Ald. Terry Gabinski prepared to retire, Burke honored him by reminding his dear friend how to cash in on his public service. You see why Burke’s conviction is such a civic loss.

Under Council rules, Burke noted, former aldermen are allowed on the floor during meetings.

“So I hope that there are a great many influential business leaders in Chicago who may be listening to this proceeding or perhaps read about it who will know that he indeed is available as a lobbyist, a consultant and adviser,” Burke deadpanned, pausing expertly for laughter.

”And just think of the remarkable access that a former member of this body has to all the members!” he continued. “He can come and circulate through the body and chat with the members and urge them to take or refrain from taking a position.”

This got an especially big laugh because a Sun-Times investigation series had recently revealed, in excruciating detail, Burke’s own ability to leverage income from his public office. The series started, for instance, by revealing that Burke had been hired as co-counsel in two lawsuits by Jenner & Block, the firm Burke hired as Finance Committee chairman to represent himself and other pro-administration aldermen in the city ward remap case. Jenner & Block earned about $8 million on that one. Burke had to withdraw as co-counsel after the Sun-Times stories. Later that meeting, when the council honored the Sun-Times' 50th anniversary with a resolution and a standing ovation, Burke didn't stand. And he didn't clap.

“Ald. Burke, you're absolutely right!” declared Ald. Dick Mell, who was both chairman of the Council’s Rules and Ethics Committee and owner of a spring factory. “If the city bought springs I would hire Ald. Gabinski to represent me, but they don't," he said.

5. June 8, 2000

As I mentioned earlier, around 1998 Mayor (Richard M.) Daley started opening every single meeting by honoring worthy police officers and firefighters, who mostly hated him. By June of 2000, resolution speeches often ran one to two hours, which I noted in my column for this meeting at the time. Everybody had to get in on it.

As I wrote then in the Sun-Times:

“The ritual goes like this: A resolution recounting heroic actions is read aloud. Ald. Edward Burke makes the first speech praising the officers. Aldermen who can claim one of the officers as a ward resident may see their chance to jump up and talk, too. Daley finishes by praising the officers and the entire Fire and/or Police department.

“Then, for the finale, Daley attacks the press for not covering good stories, and reporting anything else negative.”

Here’s Mayor Richard M. Daley’s tirade against the press that day:

“It’s our responsibility to tell the people what's truly taking place within the Fire Department and Police Department,” he huffed. “If one individual did something wrong out of the ones we honor, just one, there'd be headlines maybe for four or five days, editorials, writings, everything about one individual's conduct. But we never read an editorial, we never see a headline about the heroic deeds of men and women of the Chicago Fire Department and Police Department.”

He went on a bit longer before his theatrical finale, in which he pointed an accusing finger at the press box.

The Council and audience turned as one to follow the mayor’s finger and stare at the press box. That meant they were all staring at me, because I was the only one there.

“I always point this out, if (the police or firefighters) did something wrong, that gallery would be loaded with the press,” Daley at me and the empty chairs next to me in the press box.

Here’s the thing, though: The papers and TV news always run occasional stories about heroic police officers and firefighters. Of course they do! They’re great stories! On that particular day, it’s true none of the honored heroes had gotten media coverage. But that’s because the police and fire departments communications staff hadn’t bothered to notify the press about any of those particular heroic deeds. I checked to confirm. As I noted at the time, the press isn’t a supernatural presence suffusing the entire city, instantly aware of every good deed. If we don’t see a heroic act and the city PR people don’t care enough to tell us, it’s hard to report.

Also, negative stories may not be fun reading, but they’re darn useful. Kind of the highest purpose of journalism, when you think about it. Media attention in several tragic cases at that very time had spurred recent police training changes, and forced the city to purchase six extra life support ambulances after gun shot victims died waiting for help.

And the reason the press box was empty except for me is because everybody else was waiting outside the Council chamber door, as instructed by the mayor's press office, for a quick press conference with Daley before he left the meeting early.

Did you dig spending time in 1972? If you came to THIS CRAZY DAY IN 1972 from social media, you may not know it’s part of the novel being serialized here, one chapter per month: “Roseland, Chicago: 1972” —FREE. It’s the story of Steve Bertolucci, 10-year-old Roselander in 1972, and what becomes of him. Check it out here.

An alder is a species of tree, not a person or an office.

Now granted, alders, the tree are undoubtedly smarter than 48 of our 50 current aldermen & women, I still don't want the tree defamed by calling these corrupt morons alders!